9

The Growth Industry

Postwar psychological healers were aggressive, upbeat, and emphatically dedicated to the proposition that preventive techniques and treatment should be vigorously applied to normal people and their normal problems in normal communities. World War II, as we saw in chapter 4, had given clinicians an ominous glimpse of what could happen when healthy individual personalities were overwhelmed by unhealthy environmental stresses. Painfully aware that cures for drastic mental disturbances were flawed, if not altogether futile, they were relieved that war had presented an alternative. The agony of the desperately ill need no longer be their sole preoccupation. They could set their sights on the normal anxieties of ordinary people. And they did. In the name of prevention and mental health, clinicians pledged themselves to careers as architects of social as well as personal change.

World war ended in 1945, but the challenge of psychological adjustment endured. Combat anxieties no longer precipitated breakdown, but new social strains multiplied and spread, threatening to generate waves of civilian casualties at a moment when a country burdened by postwar reconstruction could least afford the financial and symbolic sacrifice. As if to acknowledge that unemployment, housing shortages, racial conflict, and the dawn of the nuclear age all tested the mental and emotional stamina of soldiers and citizens fatigued by years of war, the legislation that became known as the GI Bill was formally titled the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944.

Because adjustment seemed to have such positive civic, as well as personal, overtones, maladjustment was considered a national hazard. It was this specter of incomplete or failed adjustment, and the realization that psychological and social fitness were inextricably linked in any measure of social well-being, that prompted a new mood of receptiveness to the psychological duties of national government. "Not many personalities," cautioned William Menninger in 1948, "can still be in there adjusting after a full speed head-on collision with as solid a piece of Environment as a ten-ton truck."[1]

This chapter describes how clinical experts devoted themselves to the job of keeping personality and environment in stable balance, continuing the process of normalization that began between 1941 and 1945. It shows how smoothly postwar trends paralleled clinicians' preventive credo and how quickly institutional and legislative changes helped to realize clinicians' vision of an expanded jurisdiction for psychological expertise, initially facilitated by an expanding federal government. The major outlines of clinicians' historical chronology after 1945 are quite similar to those of their colleagues in the behavioral sciences. Chapter 5, for example, described the career of policy-oriented psychological experts during the early Cold War, when grave new military priorities facilitated a flow of defense dollars to experts who promised that psychological science and technology would help manage political change in a dangerous world in exchange for continued state support and a part in determining the direction of U.S. foreign and military policy.

This convergence demonstrates, yet again, the theme that divergent types of psychological experts shared important common ground. Some worked in national security occupations trying to manage revolutionary upheaval in the Third World while others worked in local clinics trying to steer individuals toward a happier existence. Some thought they were developing social and behavioral science; others considered themselves neutral technologists; still others made unwavering commitments to professional lives delivering social service and personal aid. The particulars of their stories were distinctive. The general outlines of their histories were not.

For clinicians, the lessons of World War II were also beacons illuminating their future path, but the characteristic features of postwar U.S. society, as they emerged, were equally prominent in heightening the visibility of clinical experts and increasing the popular demand for their services. Economic affluence and an ethic of avid consumption allowed

people to think of empathy and warmth as items to be purchased without recoiling from the commercialization of human connection. While the pervasive techniques of industrial psychologists contributed something to the alienation of "the organization man" (the famous William H. Whyte book by that title included an appendix on "How to Cheat on Personality Tests"), experts' promise of supportive understanding also nourished the ongoing quest for existential meaning, just as new levels of geographic mobility did by placing more people than ever out of reach of the kin and community ties with which they had grown up. Finally, an insistent ideology of patriarchal domesticity simultaneously returned civilian jobs to male veterans and sequestered women and children in a familial bubble that made private ordeals a matter of great public curiosity and untiring investigation.

It was in this context of affluence, alienation, and sharp gender distinctions that the postwar trends discussed in this chapter unfolded. Three developments in particular are described below because they illustrate the growing public influence of clinical expertise, as well as the basis of that influence in the World War II experience and the incessant militarism of the postwar years.

First, the swift acceptance by federal government of an unprecedented responsibility for the mental and emotional well-being of the entire U.S. population. With passage of the National Mental Health Act of 1946, it was apparent that the mental health of ordinary citizens would become a consequential public policy issue in its own right and the result was that more and more responsibility for its pursuit and maintenance rested with the state. Federal legislation, in turn, provided the infrastructure necessary to support a community-oriented psychology and psychiatry during the 1950s and 1960s. One oft he first and most important results was the growing conviction that psychological and social change were inseparable. Political activism was as much of a social responsibility for clinical experts as personal helpfulness was.

Second, this chapter discusses the popularity and growth of psychotherapy for "the normal." Spurred in part by veterans' requests for ongoing assistance and built on the infrastructure of new federal initiatives, this development sharply altered the geographic location, professional interests, and daily responsibilities of clinical experts. The enormous new market for psychotherapy at first caused some bewilderment among clinical professionals, who were not always as confident about the services they offered the public as they would have liked to be. But for the most part, it fostered their desires for a larger territory in which to work and added the blessings of consumer demand to their

arguments that psychological knowledge would increase in direct proportion to the normalization of its research, theory, and technologies. Experts allied with psychoanalysis and behaviorism alike agreed that "the study of psychotherapy, in distinction from the isolated study of abnormal behavior, is a description of the process by which normality is created ."[2]

Third, the emergence of humanistic perspectives within the psychological professions is examined. Presenting itself as an alternative to psychoanalysis and behaviorism, this innovative trend took wartime normalization and the postwar popularization of psychotherapy to their logical extremes. It personified the belief that an optimistic, normal psychology could provide two desperately needed prerequisites for a nation seeking renewal and revitalization—mental health and democratic behavior—neither of which had been much in evidence during World War II. Practitioners like Carl Rogers and theorists like Abraham Maslow, whose work is briefly reviewed below, advanced ideas about the inherent goodness of motivation and the primacy of subjectivity in psychology, in science, and in all human affairs. They boldly insisted on clinicians' ability to generate positive insight and mature behavior and they tirelessly popularized their own work. Humanistic approaches eventually contributed to a fundamental shift in the ideas of 1960s social movements, where "the political" was reconceptualized to encompass "the personal" and notions of social responsibility were saturated in the vocabulary of subjective experience.

The State as Healer: Mental Health as Public Policy

Taking charge of unpredictable emotions and reactions in persons and populations had not been merely, or even mainly, a humanitarian effort during the war years, nor would it be one after 1945. If at times it was presented as a matter of sheer altruism, it really was not. The job of maintaining mass emotional control was decisively taken up by the federal government in the postwar decades because it was understood that mental health was necessary to the efficacy of the armed forces in the short run and national security, domestic tranquillity, and economic competitiveness in the long run. Who could forget the shocking epidemic of emotional disorder and disability exposed during World War II? Ensuring a sufficient threshold of mental stabil-

ity, because that threshold undergirded the integrity of social institutions, became a new and important sphere of federal action in the postwar decades.[3]

Prior to the war, public accountability for disturbed psychological life had rested largely with individual states, which provided an uneven patchwork of custodial services to the mentally ill in segregated institutions. After the war, federal policy-makers absorbed the lesson that it was more efficient, forward-looking, and quite possibly cheaper to take preventive action on behalf of mental health than face the demoralizing, long-term prospect of treating the chronically sick. Asylums would continue to exist, of course, and states would have to sustain and even improve them. The federal government, however, would design its new role on the basis of what clinicians believed they had learned during World War II: that mental health and illness were relative, rather than fixed states; that mental illness could be prevented with early, assertive clinical intervention; that normal adjustment to internal and external strains was a lifelong project, never permanently accomplished and always in need of vigilance.

Above all, federal mental health policy after 1945 was built on and furthered the integration of clinical and social-scientific insights, helping to merge the concerns of emotional guides and social engineers, so that by the late 1960s, movements for community mental health had effectively undermined the legitimacy of distinctions between private emotions and public policy, between clinical work and the business of politics and government.

The Role of the Veterans Administration

Even before the end of World War II, the record of the Veterans Administration (VA) clearly indicated that some federal agencies were prepared, even eager, to support vast new programs in the mental health field. The VA, of course, had little choice in the matter; next to the armed forces themselves, it was the agency whose primary job was to care for war casualties. Since huge numbers of those casualties had suffered psychiatric breakdown, the VA found itself in charge of binding more mental than physical wounds and picking up the emotional pieces of military conflict.

The number of psychiatric cases in VA hospitals almost doubled between 1940 and 1948.[4] Right after the war, in April 1946, around 60

percent of all VA patients were neuropsychiatric cases of one sort or another: forty-four thousand out of a total of seventy-four thousand.[5] Fifty percent of all disability pensions were being paid to psychiatric casualties and, by June 1947, the monthly cost of such psychiatric pensions was $20 million, with each case running the government something more than $40,000.[6] The VA's fifty-seven outpatient clinics served over one hundred thousand additional people. By the mid-1950s, half of all the hospital beds in the country were being occupied by persons with mental illness, a fact called the "greatest single problem in the nation's health picture" by the March 1955 Hoover Commission study of federal medical services.[7] The VA, alone responsible for 10 percent of the inpatient total and providing ongoing treatment to thousands upon thousands of outpatients, was making ambitious plans for new construction of hospitals and clinics.[8] Waiting lists for clinical services were long and growing rapidly.

Because personnel shortages had been so severe during the war, and psychiatrists, psychologists, and other clinicians were so scarce, professional training soon became "the most pressing medical problem" facing the agency, according to Dr. Daniel Blain, chief of psychiatry in the VA.[9] Indeed, more open positions existed in the VA at war's end for clinical psychologists than there were clinical psychologists in the entire country. In order to cope with the prospect of drastic, long-term personnel shortages, programs of professional education were swiftly put into place.

An ambitious four-year training program in clinical psychology, for example, was launched in 1946 to train two hundred individuals in twenty-two different universities.[10] Under the terms of the program, students were given free educations and prorated salaries in exchange for half-time work in a VA facility while they pursued their doctoral degrees. This instantly made the VA the single largest employer of these professionals in the entire country. In 1946, the VA's chief of clinical psychology wrote, "The significant and inevitable consequence of this development is that a large portion of the whole profession of clinical psychology will come under Governmental control. . . . The field is rapidly expanding and the opportunities for service and research are almost limitless."[11] The VA continued to produce hundreds of new clinicians each year, all of whom could expect interesting work and substantial pay in a job market where their skills were in high demand. Just three years into the clinical psychology program, it had expanded to seven hundred students in forty-one universities.[12] This pattern of steady

growth, which lasted for decades, ensured that the VA would remain the source of plentiful, exciting professional opportunities and contributed to a massive shift in employment patterns within psychology away from academia and toward clinical work. The year 1962 was, R. C. Tryon noted, "a real turning point" because psychologists employed outside of universities outnumbered their academic colleagues for the first time.[13] Opportunities were not limited to clinical psychology. By the mid-1950s, the VA was employing 10 percent of all psychiatrists in its 35 psychiatric hospitals, 75 general hospitals with psychiatric services, and 62 mental health clinics; another 10 percent of psychiatrists worked as VA consultants.[14]

The VA proved a bonanza not only for clinical professionals. It was also the site of increased consumer demand. Veterans and members of veterans' families, most exposed to clinical expertise for the first time during the war, were the first to come looking for assistance with the ordinary—if still extremely difficult—problems of postwar living. It must be recalled that the vast majority of veterans who received discharges for psychiatric reasons were classified as suffering from the lower orders of mental disturbance: psychoneurosis rather than psychosis. These veterans and others tended to bring "normal" problems to the attention of VA clinicians: marital tensions and parenting difficulties were especially common.[15]

Some veterans undoubtedly remained skeptical that professional helpers could be of any practical use. If the statistics on skyrocketing numbers of VA outpatients are any indication, however, many others had received the message that had been directed at them repeatedly as soldiers: nothing was wrong with seeking psychological help; in fact, to do so was a sign of unusual strength and maturity. Quite a few clinicians who worried about the logistical headaches of servicing millions of returning soldiers reminded themselves that offering clinical assistance to the civilian masses was the logical follow-up to their earlier patriotic contributions in the military. Dispensing psychotherapy to veterans was the link connecting clinicians' past to their future.

Psychotherapy could also advance the process of social readjustment to peacetime democracy. Carl Rogers, for example, was a clinician who would become a well-known advocate of humanistic psychology in the postwar decades. In 1946 he coauthored a counseling manual, Counseling With Returned Servicemen, that he hoped would put simple, do-it-yourself therapeutic techniques into the hands of thousands of new clinicians so that they might ease the adjustment traumas of returning

servicemen whose subjection to strict military authority had temporarily unfitted them for their postwar roles as free-thinking, independent citizens. He spelled out the social relevance of their collective task as follows: "No longer is he just another G. I. Joe. Instead he again becomes Bill Hanks or Harry Williams. In contrast to marching troops who are 'men without faces,' the client begins to resume selfhood as a specific, unique individual."[16] Not only did Rogers promise that his particular brand of sensitive, nonjudgmental clinical help could facilitate the resumption of selfhood and individuality. It could also help to recapture any democratic impulses that had been lost in the crush of wartime regimentation, and perhaps even generate attractive new styles of democratic conduct and decision making in individuals who had never previously possessed them. "All the characteristics of this type of counseling," Rogers contended, "are also tenets of democracy."[17] Surely a voluntary therapeutic relationship consciously imbued with tolerance and respect, based on confidence in individual maturity, freedom, and responsibility, might succeed in communicating some of these virtues to veterans.

The National Mental Health Act of 1946

The most tangible evidence that citizens' mental health had been elevated to a major priority of federal government came with passage of the National Mental Health Act (NMHA) of 1946.[18] This landmark piece of legislation was inspired in large part by the dismal record of military mental health during World War II, the performance of such agencies as the VA, and vocal demands by veterans and their families for therapeutic services. Clinicians too mounted persistent advocacy efforts on their own behalf, convinced that gains in professional visibility and prestige would result from increased federal funding. For them, as for their ambitious colleagues who wished to influence postwar foreign and military policy, military experiences and mandates were both genuinely transforming and politically expedient. War had been, and would continue to be, a great persuader.

Called the National Neuropsychiatric Institute Act when it was first introduced in Congress in March 1945, the legislation's final title incorporated the term "mental health," an alteration that captured the pivotal role of World War II and its marked clinical drift toward normalization. Indeed, leading figures in wartime clinical work were conspicu-

ous in the lobbying effort for the NMHA, and the lessons they had learned on the job, maintaining military mental health, were the most frequently heard arguments in favor of government action in this area.

Robert Felix, a psychiatrist who had been appointed director of the Public Health Service's (PHS) Division of Mental Hygiene in 1944, put most of his own energy, and his bureaucracy's muscle, into passing the bill. William Menninger, Lawrence Kubie, and others testified about how shortages of trained clinicians had sometimes thwarted military morale and how early therapeutic intervention had eventually helped the war effort by conserving personnel. They promised that federal support for professional training, research, and preventive services to the public would ease the postwar transition, humanize the face of government, and save lots of tax dollars. General Lewis Hershey, director of the Selective Service System, trotted out statistics on rejection and discharge rates from the armed services.[19] These numbers became something of a mantra during the congressional deliberations on the NMHA. It was a fact that mental illness cost a lot of money. It was simply presumed that mental health would not. The chief of Bellevue Hospital's Psychiatric Division, S. Bernard Wortis, put it as follows: "Health, sir, is a purchasable commodity, and it seems to me that if more money were put into services and brains, rather than into bricks . . . much miser), and much mental illness could be saved in this country."[20]

Advocating that mental health, rather than mental illness, be the centerpiece of federal policy also embodied clinicians' crusade for a larger jurisdiction for psychological expertise. That clinical insights should be applied to most or even all areas in need of government planning in the postwar era—from employment and housing to race relations—was assumed to be self-evident. Rarely did advocates offer concrete reasons why clinicians should be granted standing in such matters, but then, they were hardly ever asked to do so. A solitary dissenting voice at the congressional hearings on the NMHA illustrated the extent of expert consensus on the importance of expanding clinicians' social authority.[21] Lee Steiner, a member of the American Association of Psychiatric Social Workers, cautioned, "If we include these [diverse social policy] problems as 'preventive psychiatry,' then all problems of life and living fall into the province of the practice of medicine."[22] Her reservations, although they stand out to the contemporary reader, were buried at the time in the avalanche of certainty that clinicians could be trusted to discover the solutions to "all problems of life and living."

Almost as rare as dissenting expert testimony was nonexpert opinion. One consumer, a Marine Corps aviator, added the drama of personal witness to the congressional proceedings. Captain Robert Nystrom, who had recently recovered from manic depression, described what he had learned during his five-month hospitalization at St. Elizabeth's. He contrasted the worthless "loafer's delight" treatment he received initially with the "sort of streamlined psychoanalysis" that eventually helped him develop insight and recover function during two weekly sessions with a therapist.[23] If the NMHA were not passed, he warned, do-nothing remedies would be the awful fate of all Americans afflicted with debilitating mental troubles, and the country would be the worse for it. His story made a deep impression.[24]

The message that decisive federal action on mental health was both imperative and intelligent got through to policy-makers and politicians. According to Senator Claude Pepper (D-Fla.), the main sponsor of the legislation in the Senate, "the enormous pressures of the times, the catastrophic world war which ended in victory a few months ago, and the difficult period of reorientation and reconstruction, in which we have as yet achieved no victory, have resulted in an alarming increase in the incidence of mental disease and neuropsychiatric maladjustments among our people."[25] With "the improvement of the mental health of the people of the United States" as its stated goal, the NMHA was signed into law by President Truman on 3 July 1946. It provided financial support for research into psychological disorders, professional training, and grants to states for mental health centers and clinics. According to William Menninger, the salutary results of federal largesse were felt almost immediately. Within one year, every state had designated a state mental health authority, 42 states had submitted comprehensive mental health plans to the federal government, 59 training and 32 research grants had been awarded, and 212 students were on their way to becoming clinical professionals thanks to federal stipends.[26]

The NMHA also laid the groundwork for the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and authorized funds for its construction. The NIMH, when it was formally established in 1949, replaced the Public Health Service Division of Mental Hygiene and was placed under the administrative umbrella of the National Institutes of Health. Robert Felix was named its first director. Publicly allied with reformers like Menninger and reform organizations like the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry, Felix faithfully steered the new agency on the course that World War II and professional ambitions had specified. At

the outset, he summed up his purpose as follows: "The guiding philosophy which permeates the activities of the National Institute of Mental Health is that prevention of mental illness, and the production of positive mental health, is an attainable goal."[27] This optimistic, preventive vision inspired Felix "to help the individual by helping the community"—an apt slogan for the community mental health movements that would shortly materialize on the cutting edge of clinical work.[28] By the time he retired in 1964, Felix had been widely credited with prodding the federal government out of the dark ages of indifference toward mental illness and health.

As a result of its preventive, community-sensitive orientation, the NIMH became the key institutional patron of an expansive (and expensive) mental health program during the postwar decades, one that consciously mingled the insights of clinical expertise and behavioral science. Felix appointed a panel of social science consultants as soon as the NIMH was founded and charged members with recommending ways that interdisciplinary social research could further the goal of national mental health. He named several individuals to the panel who had played key wartime roles, championing the utilization of clinical theories to achieve practical policy aims. Margaret Mead, Ronald Lippitt, and Lawrence K. Frank were among them.[29]

The abundant and ever-increasing funds that the NIMH offered to psychological professionals were an important reason for the healthy economy in mental health fields in the 1950s and 1960s. During 1950, its first year of operation, the NIMH budget was $8.7 million. Ten years later, it was over $100 million, and by 1967, it was $315 million.[30] In 1947 total federal expenditures for health-related research of all kinds had been around $27 million.[31] As the government's research program expanded in the years after World War II, far outstripping private sources of funding, the proportion devoted to mental health increased dramatically. In 1947 it was allotted a mere 1.5 percent of federal medical research dollars; just four years later, in 1951, its share had risen to almost 6.5 percent.[32] Only four other areas of medical research were granted more money than mental health in the five years after the war: general medical problems, heart disease, infectious disease, and cancer.[33] By the early 1960s, mental health had outpaced heart disease, but the precipitous rise in available dollars did little to silence critics of government spending priorities, who continued to insist that the public research investment in mental health was shortsighted and stingy when compared to the costs of mental illness.[34]

Although hardly in a position to be as generous as the Department

of Defense, the NIMH was nevertheless a major benefactor of fundamental research in the social and behavioral sciences by the late 1960s. On the theory that any and all research related to mental health deserved support, the NIMH financed everything from anthropological fieldwork abroad to quantitative sociological "reports on happiness" at home.[35] Its impact was felt on research concerned with racial identity, conflict, and violence and it gave staff and other resources to the Kerner Commission investigations, as we have already seen.

By the early 1960s, NIMH was spending significantly more on psychological and cultural studies of behavior than it was on conventional medical inquiries into the biological basis of mental disease.[36] In 1964, 60 percent of NIMH research funds were given to psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists, and epidemiologists; only 15 percent of the budget went to psychiatry, with an additional 21 percent going to other biologically oriented sciences.[37] Such conspicuously social priorities were compatible with the community emphasis of mental health research and practice, the enhanced status of behavioral science, and the dominance of psychodynamic perspectives among clinicians during the 1950s and early 1960s.

Community Mental Health as an Expression of Clinical Social Responsibility

In the years after the passage of the NMHA, several other developments within the professions and on the federal level sustained the forward motion of clinical experts by further institutionalizing opportunities for professional training and fostering clinicians' social influence through a process of integration with the social and behavioral sciences. The formation of the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry (GAP) in the spring of 1946 embodied the reforming zeal of "young Turks" with a background in military mental health.[38] Led by William Menninger, GAP was initially conceived as a pressure group within the American Psychiatric Association. During the next couple of years, GAP members captured most of the top posts in the American Psychiatric Association, including the presidency. But GAP soon blossomed into an autonomous organization whose influential working groups and published reports championed social conscience and liberal political activism and whose professional campaigns carried the banner of community mental health.

In July 1950 GAP's Committee on Social Issues published a mani-

festo, rifled "The Social Responsibility of Psychiatry," which made GAP's political proclivities explicit. In draft form, the committee pledged itself to social reform: "We feel not only justified, but ethically compelled to advocate those changes in social organization which have a positive relevance to a program of mental health."[39] The final document was somewhat more moderate in tone, but its activist commitment was indisputable.

The Committee on Social Issues has the conviction that social action . . . implies a conscious and deliberate wish to foster those social developments which could promote mental health on a community-wide scale. . . . We favor the application of psychiatric principles to all those problems which have to do with family welfare, child rearing, child and adult education, social and economic factors which influence the community status of individuals and families, inter-group tensions, civil rights and personal liberty. The social crisis which confronts us today is menacing; we would surely be guilty of dereliction of duty did we not make a conscientious effort to apply whatever partial knowledge we now possess in the interests of counteracting social danger and promoting healthier being, both for individuals and groups. This, in a true sense, carries psychiatry out of the hospitals and into the community.[40]

Although there was some resistance to GAP's emphatically social interpretation of psychiatric responsibility within the profession at large, which had a long history of concern for the somatic causes of mental disorder as well as for severely ill individuals, no such resistance existed within the surging ranks of psychology.

Clinical psychology, after all, was practically a brand-new profession after World War II. It was searching for a fresh identity within a newly reorganized American Psychological Association (APA) that had defined its general purposes in unmistakably visionary terms from the very first. As Robert Yerkes put it, at the APA's Intersociety Constitutional Convention in 1943,

The world crisis, with its clash of cultures and ideologies, has created for us psychologists unique opportunity for promotive endeavor. What may be achieved through wisely-planned and well-directed professional activity will be limited only by our knowledge, faith, disinterestedness, and prophetic foresight. It is for us, primarily, to prepare the way for scientific advances and the development of welfare services which from birth to death shall guide and minister to the development and social usefulness of the individual. For beyond even our wildest dreams, knowledge of human nature may now be made to serve human needs and to multiply and increase the satisfactions of living.[41]

Clinical psychologists found that the "birth to death" ideology of the welfare state corresponded perfectly with their own aim to normalize

clinical practice and expand their sphere of social authority, even when those aims—the autonomous practice of psychotherapy was perhaps the most striking—conflicted directly with the interests of organized psychiatry.

GAP's record illustrated that advocating social change in the name of improved mental health could produce both very rewarding professional and very unpredictable political results. By insisting that mental balance involved a constant state of adjustment and exchange between self and society, clinical experts could, and did, lay claim to defining what was normal in environments as well as in people. "This view of the fluidity of the interaction of the individual with society," GAP pointed out, "tends inevitably to broaden the concepts of mental illness and mental health."[42]

They did not add that it inevitably broadened the authority of psychological experts as well by giving them power to designate exactly how social institutions—economic, familial, educational, and so on—might prevent mental trouble and nourish emotional well-being. Doing so, needless to say, was extremely controversial. GAP's impeccable liberal credentials led members to endorse a social program of racial harmony, literacy, economic security, and family happiness, among other things—all founded on an expanded role for psychologically enlightened federal government. One of the best known and most widely circulated GAP reports, for example, was issued in 1957. Titled "Psychiatric Aspects of School Desegregation," there was no mistaking its immediate relevance, and support for school integration, in the face of the fierce white resistance that followed Brown v. Board of Education .[43]

Yet even more disagreement accompanied any definition of "normal" social structure than did the definition of "normal" individual psychology. (Whether or not racial integration qualified as one component of a normal environment was just the tip of the iceberg.) The climate of domestic anticommunism in the late 1940s and early 1950s also emboldened GAP's critics. At various points, the organization was accused of being a "radical sectarian group" full of Communist sympathizers intent on seizing control of the psychiatric profession.[44] GAP members responded to McCarthyism by dashing off a report, "Considerations Regarding the Loyalty Oath as a Manifestation of Current Social Tension and Anxiety," but political name-calling caused barely a momentary interruption in their crusade to have clinical experts act on their social responsibilities, as GAP saw them.[45]

In 1955 Congress passed the National Mental Health Study Act,

paving the way for the Joint Commission on Mental Illness and Health (JCMIH). GAP members and others who shared an activist clinical philosophy believed the government had taken another decisive and enlightened step toward broadening its jurisdiction over mental health, superseding the decentralized tradition that had left policies in the hands of bungling and backward state politicians.[46] The purpose of the JCMIH (which, although a nongovernmental body, was almost entirely funded by the NIMH) was to conduct an encyclopedic survey of mental illness and health in preparation for innovative new national policy initiatives. Thirty-six participating organizations (which included the Department of Defense, the American Legion, and the American Psychiatric Association) spent several years and $1.5 million on this project and published ten scholarly monographs in addition to its final report, Action for Mental Health. The final report reiterated at the outset the fundamental equation between democracy and mental health that had been a constant refrain during and after World War II. Their assigned task of developing mental health policy, wrote the authors, "is our responsibility as citizens of a democratic nation founded out of faith in the uniqueness, integrity, and dignity of human life. . . . Good mental health. . . is consistent with this higher responsibility and with our professional and political ideals. It is also consistent with what the American people should want—not simply peace of mind but strength of mind."[47]

During its tenure, the JCMIH compiled a mass of data with numerous possible interpretations, but its staff and major constituencies all wished to promote the delivery of community-based services geared to prevention. According to the JCMIH studies, new, milder forms of psychotherapeutic intervention in communities across the country were worth a real try, even though intensive custodial care was in dire need of improvement. Several of its core recommendations were used by the Kennedy and Johnson administrations in the years that followed to move the federal government toward the next policy phase: establishing community mental health centers throughout the country. In this regard, an especially significant suggestion was that funding more outpatient services through community centers would result in cutting hospitalization rates (i.e., prevent at least some cases of incapacitating mental illness). The JCMIH proposed one center for every fifty thousand people.[48]

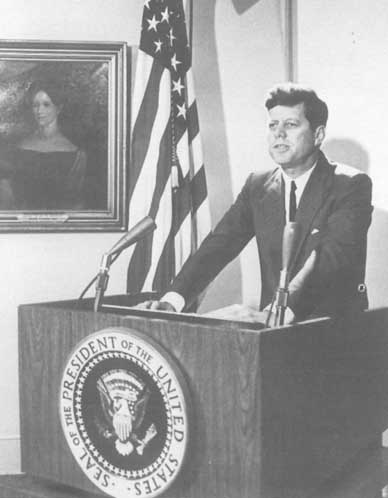

In 1963 President Kennedy (whose younger sister Rosemary had

undergone psychosurgery after being diagnosed with mild retardation) became the first U.S. president to make mental illness and retardation the subjects of a special address to Congress (fig. 16). Surely this was conclusive proof that the mental and emotional status of U.S. citizens had become a pressing government concern. Kennedy's speech elated the boosters of a socially active and expansive federal policy because the president highlighted the criticisms and proposals that advocates of preventive and community mental health had been repeating for years: during World War II, in the course of passing the NMHA, and in organizations like GAP.

First, Kennedy disparaged a decentralized policy approach and accused states of neglectful reliance on "shamefully understaffed, overcrowded, unpleasant institutions from which death too often provided the only firm hope of release."[49] Then he proclaimed that "an ounce of prevention is worth more than a pound of cure."[50] Only a new federal campaign to fund research, professional training, and community-based services would replace "the cold mercy of custodial isolation" with "the open warmth of community concern and capability" and, Kennedy optimistically projected, reduce the number of institutionalized patients by 50 percent in "a decade or two."[51] Shortly afterwards, the Mental Retardation Facilities and Community Mental Health Centers Construction Act of 1963 was passed. Federal grants for the construction of community mental health centers were its main feature; a total of $150 million was appropriated for this purpose during the following three fiscal years.[52] The long-term goal (never to be realized) was to establish a national network of two thousand centers, one for each geographically defined community of 75,000 to 200,000 people. Even observers who worried that care for the most severely ill might suffer endorsed the expanded sphere of authority that the act gave to clinical professionals and pronounced it "the most significant development in recent history in the provision of services for the mentally ill."[53]

The combined efforts of policy-makers and professional advocates, and the tenor of national mental health legislation in the decades after 1945, turned the ideology of community mental health into an expression of clinical experts' social responsibility. Based on the sunny supposition that mental health could be manufactured (and illness prevented) if only the environmental conditions were favorable, clinicians marched boldly into a variety of fields—from criminal justice to education—to guarantee that they would be.[54]

Figure 16. President Kennedy addressing Congress on 5 February

1963 on the subject of mental illness and retardation.

Photo: No. AR 7698A in the John F. Kennedy Library.

Claiming that all aspects of community life potentially affected individual mental health, psychiatrists redefined their clinical mission as follows: "Within our definition, all social, psychological, and biological activity affecting the mental health of the populace is of interest to the community psychiatrist, including programs for fostering social change, resolution of social problems, political involvement, community orga-

nization planning, and clinical psychiatric practice."[55] A typical formulation of community psychology simply identified it with the "optimal realization of human potential through planned social action."[56]

That something as undeniably positive as mental health could justify a process of social reform had obvious appeal during a period of dynamic grassroots and governmental activism. During the late 1950s and 1960s, an array of progressive social movements repeatedly called for equalizing changes in the distribution of political power and material resources, and the federal government responded with nothing less than the War on Poverty and the Great Society. The impetus for community mental health had, after all, come from clinicians with liberal political sympathies in the 1940s and 1950s. When the political climate shifted further to the left in the 1960s, clinicians moved a bit further to the left as well, but they continued to advance a vision that merged psychological change with social activism and responsibility. Community mental health, they were convinced, was intimately bound up with campaigns to eliminate racism, poverty, and oppression and forge a better, more humane, society. Mental health was all but synonymous with equality, prosperity, and social welfare.

It was not long, however, before radicals began to question these happy political assumptions, a process we have already seen at work in the case of psychological approaches to the problems of rioting and revolution confronted by police forces and militaries. "Sick" social environments stubbornly resisted clinicians' most well intentioned cures; ghettos remained poor and schools impoverished. How could adjustment between self and society be accomplished, or even advocated, when so many people led such wretched lives? Perhaps psychological adjustment only adjusted people to habits of powerlessness, inequality, and anguish?

By the late 1960s, the frustrating slowness of change had generated the beginnings of a skeptical, even cynical, countermovement that turned the heady idealism of the postwar years on its head. Suspicions that psychological expertise might have oppressive consequences diametrically opposed to stated intentions spread, sometimes as a result of organizing by former mental patients who bluntly denounced the treatment they had received at the hands of the mental health professionals, sometimes as a result of the advocates of "radical therapy," who aimed to merge therapeutic insight and leftist politics. Under the harsh light of this new criticism, the community mental health movement no longer appeared as an enlightening crusade, but rather as one element

of a multifaceted scheme to subvert genuine democracy through a disguised program of social control. One writer, Chaim Shatan, speculated in 1969 that "the clinicians will provide emotional first aid, while the government-subsidized conveyor belt feeds manpower directly into federally sponsored operations—from the space race to community mental health itself. . . . In 1984, Big Brother may be a community psychiatrist."[57]

In March 1969 Lincoln Hospital Mental Health Services, located in the South Bronx, was taken over by its nonprofessional staff members, most of them black and Puerto Rican.[58] The center epitomized the ideals of the community mental health movement; there was a walk-in clinic for neighborhood residents, a program of consultation with community organizations, and so forth. But the protesters were fed up with the paternalism of well-intentioned white psychiatrists, as the text from their flyer made clear.

We're gonna see what you do with what you think is your center. You honkies complain that we don't respect authority and we don't want any compromise. Damn right. Your authority is no good and we've been compromising too damn long. So now you listen to what working people are saying loud and clear. And you better listen: Cause now we're not working for the center anymore. We and the community are the center.[59]

After fifteen days of occupation, during which the protesting workers appointed new department heads and issued a lengthy list of demands, the administration caved in. The center promptly changed its name, hired a new director, and severed its ties to the hospital (and the department of psychiatry at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, with which it was affiliated).

This episode, now famous as a turning point in the history of the community mental health movement, propelled forward the new spirit of negativity about the political function of clinicians and strengthened the view that community mental health was so much rhetoric plastered over an unattractive reality of domination by elites. Significantly, however, the target of the most withering criticism was the inequality between professionals and nonprofessionals. Even the Bronx protest re-emphasized the liberating potential of psychological knowledge in the hands of disenfranchised people. As long as it was not monopolized by experts, community psychology "gave a voice to people who had been kept outside of history."[60] For a number of years after the 1969 takeover, the Lincoln Community Mental Health Center offered a range of

alternative, largely nonprofessional mental health services to residents in the South Bronx.

Psychotherapy for the Normal as a Postwar Growth Industry

The doubts that began to cramp clinicians' high spirits by the late 1960s were somewhat removed from the concerns of the general public. During the years after 1945, ordinary people sought therapeutic attention more insistently than ever before and for more reasons than ever before. While the direction of federal policy may have helped to push clinicians out of asylums, the explosion in public interest was at least as pivotal in pulling clinicians into the lives of ordinary citizens. Gushing demand for psychotherapy was much discussed by clinicians. Even dissenters like C. C. Burlingame, the director of the Hartford, Connecticut, Institute for Living and a staunch advocate of psychosurgery, who denounced the prevalent mood of therapeutic optimism as "psychiatric nonsense," admitted that "it has come to be quite the fashion to have a psychoneurosis!"[61] Unlike Burlingame, most experts welcomed the surge in popular demand as evidence of a sort of public enlightenment "peculiar to the United States."[62] They were quick to herald it as "one of the remarkable features of our culture," whether they understood it or not.[63]

We have already seen that, in the wake of world war, new federal laws, bureaucracies, and funding embraced the changing emphasis from mental illness to health, spurred along by reenergized old and new professional pressure groups. By generating a new, publicly supported infrastructure for training, research, and service delivery in mental health fields, the federal government contributed to the migration of clinical experts out of isolated institutions devoted to insanity and into the heart of U.S. communities. A 1948 survey conducted by the American Psychiatric Association found that 35 percent of its members were already primarily engaged in private practice.[64] The 1954 introduction of the first psychoactive drug, chlorpromazine (known by the trade name Thorazine), accelerated the trend, already under way, toward emptying traditional institutions. In 1956 the total number of patients residing in public mental hospitals declined for the first time since the nineteenth century, and the deinstitutionalization process picked up speed in the

mid-1960s.[65] In 1957 only 17 percent of all American Psychiatric Association members were still charged with supervising custodial care to severely and chronically ill individuals in state or VA hospitals, the sort of institutions where virtually all psychiatrists had been located prior to 1940.[66]

The new policy emphasis on deinstitutionalization was conveniently compatible with the case for normalization, delivery of preventive clinical services, and expansion of experts' authority and jurisdiction. Indeed, these factors were mutually reinforcing. The standard argument was that outmoded and ineffective institutional care would be replaced by more efficient and enlightened services delivered in a community setting. The community mental health movement, as it turned out, did not cause the numbers of institutionalized mental patients to drop.[67] Rather, changes in federal programs during the 1960s—especially the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in the 1965 amendments to the Social Security Act—shifted elderly and chronic patients out of state hospitals and into nontraditional institutions as states quickly took advantage of new funding sources.

Advocates' rhetoric notwithstanding, the movement into the community neither replaced the old system of public mental institutions, nor adequately cared for severely and chronically mentally ill individuals, most of whom were simply moved from a publicly funded custodial setting to one in the private sector, typically a nursing home. In retrospect, it appears ironic that the expansion of the welfare state, with which liberal clinical reformers identified so strongly, undermined public commitments to the mentally sick and ushered in an era during which the logic of cost containment superseded the ethic of care. Ardent critics of the policy have consequently accused reformers of "ideological camouflage" and deinstitutionalization of "allowing economy to masquerade as benevolence and neglect as tolerance."[68] Historians more sympathetic to policy reformers after World War II point to the fact of human fallibility, the impossibility of determining all consequences in advance, and the dangers of retrospective judgment and arrogance.[69]

If it failed to achieve its stated goals, community mental health did succeed in providing new services—far more psychotherapeutic in emphasis—to a new clientele—far larger, better educated, and more middle-class. This accomplishment reflected a sharp reorientation of professional interests and a decided expansion in the market for therapeutic services among normal individuals. Increases in the sheer num-

bers of psychiatrists were startling in the postwar decades—professional association membership grew from 3,634 in 1945, at the end of World War II, to 18,407 in 1970—and the percentage of medical school graduates choosing to specialize in psychiatry ranged from a high of 7.1 percent right after the war to 6.4 percent at the end of the 1960s, numbers two to three times greater than the 1925-1940 period.[70] Institutional care faded as the center of professional gravity it had once been. Psychiatric staff positions in public mental facilities were notoriously difficult to fill, with openings running around 25 percent nationally in the mid-1960s.[71]

By the late 1950s and 1960s, most psychiatrists were either self-employed in private office practice or worked in educational institutions, government agencies, or the growing number of community clinics that catered to a "normally neurotic" clientele. In order to help veterans adjust to student life, the VA sponsored programs that expanded counseling on the university level and in 1958, the National Defense Education Act created sixty thousand jobs for an entirely new type of professional—the school guidance counselor—making individual testing and deliberate self-inspection an ever more routine feature of young students' lives.[72] In outpatient clinics exclusively devoted to adult mental health, according to one 1955 estimate, at least 233,000 people annually were already receiving outpatient psychotherapy.[73]

Clinical psychology underwent an especially rapid process of professionalization after World War II, spurred by the popularization of psychotherapy as well as by government generosity. In 1947 the American Psychological Association gave its institutional stamp of approval to the mushrooming practice of psychotherapy when it made clinical training a mandatory element of graduate education in psychology.[74] The first effort to take stock of feverish postwar efforts to establish new training programs in clinical psychology came in August 1949 in Boulder, Colorado. Thanks to an NIMH grant, seventy-one psychologists from around the United States met to consider the future of clinical training on the graduate level. There was great excitement about future opportunities in the field, a feeling reflected in NIMH Director Robert Felix's opening comments. "The mental health program is going forward, and neither you nor I nor all of us can stop it now because the public is aware of the potentialities."[75]

Problems were nevertheless immediately apparent. Although no one present at the conference seemed to know exactly what a clinical psychologist was or what a clinical psychologist did, they quickly agreed

that a doctoral degree was necessary to do it. The Ph.D. was necessary "to protect the public and to create some order out of the present confusion" because "in the public mind there is considerable confusion of the professionally trained clinical psychologist with the outright quack."[76]

What to do about the practice of psychotherapy in particular was equally baffling but probably more pressing and definitely more controversial. Conference attendees were aware of the need to balance the huge market for this service against the many unresolved questions surrounding its practice and outcomes. "Social needs, demands for service, and our own desire to serve effectively have compelled us to engage in programs of action before their validity could be adequately demonstrated."[77] Pressured to respond to public demand, they were still at a loss to describe psychotherapy or list its benefits with even minimal precision. The only definition of psychotherapy generating consensus was so general that it was of negligible use in planning training programs. According to the conference record, "psychotherapy is defined as a process involving interpersonal relationships between a therapist and one or more patients or clients by which the former employs psychological methods based on systematic knowledge of the personality in attempting to improve the mental health of the latter."[78]

Because the practice of psychotherapy was evidently as vague as it was popular, little agreement existed about the type of educational preparation required to make a good therapist, but much agreement existed that more good therapists were needed. Should therapists-in-training be required to be in psychotherapy themselves? Did students aspiring to careers as therapists really need rigorous training in scientific research methods? No one was certain. One sarcastic, unidentified conference participant summarized the muddled thinking on this question. "Psychotherapy is an undefined technique applied to unspecified problems with unpredictable outcome. For this technique we recommend rigorous training."[79]

The details governing psychotherapy and its practice remained contentious matters among the experts long after the Boulder conference. The first really damaging critique, in fact, came more than three years later from Hans Eysenck. Eysenck was a British psychologist with a reputation as a hard-nosed experimentalist whose career had taken a sharp turn toward clinical work during World War II; he eventually taught the first British course on clinical psychology. In 1952 Eysenck

suggested not only that no evidence of psychotherapy's tangible benefits existed but that there was "an inverse correlation between recovery and psychotherapy."[80] Ironically, Eysenck's heresy provided psychotherapy's defenders with years' worth of work. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, they assiduously devised ever more creative ways to define and measure psychotherapeutic outcomes and this new field of scientific research evolved into a small industry.[81]

Then there was the very delicate question of how clinicians in psychology or other professions should negotiate with psychiatrists, who had always monopolized psychotherapy and uniformly opposed its practice by other professionals.[82] The forces of organized medicine repeatedly asserted that "psychotherapy is a form of medical treatment and does not form the basis for a separate profession."[83] According to many physicians, the psychologist should have been grateful to play a limited and subordinate role similar to that played by the nurse in general medicine, who, they pointed out with some annoyance, was far more likely to understand "her" place.[84]

None of this did much to slow experts outside of psychiatry, who grew ever bolder in their claims to autonomous practice as the definition of psychotherapy stretched. To them, it was a service "sought by people who do not think of themselves as ill but who wish to avail themselves of something they believe to be good for them, and it is offered by people who consider not that they are treating disease but that they are aiding in the realization of certain ethical values."[85] The struggle over whether psychotherapy treated the health of the body or the existential status of the soul and social welfare of humanity resulted in an ongoing professional "cold war."[86]

Outside the professions, these turf battles hardly mattered. The popularization of psychotherapy proceeded rapidly during the postwar decades, becoming a staple in drama, films, and on television.[87] Most of the cultural images were highly exaggerated. Psychological interpretation, as often as not, appeared to involve pat formulas, and portrayals of mental health professionals included malevolent abusers and incompetent fools alongside caring father figures and magical healers.[88] Aware that their talents were being put to cultural tests at least as rigorous as the scientific proofs prized within the professions, organizations like the American Psychiatric Association actively lobbied in Hollywood and elsewhere to safeguard good public relations and avert unflattering stereotypes.[89] Whatever damage the professionals feared to their collective reputation was clearly outdistanced by the almost insatiable public

demand for accessible, entertaining information about who mental health experts were and what they did.

Psychotherapy was also an experience in which more and more people participated directly (fig. 17). By 1970 approximately twenty thousand psychiatrists were ministering to one million people on a purely outpatient basis.[90] Well over ten thousand psychologists were providing some type of counseling service, more than were involved in any other single area of work, and close to half of all doctoral degrees in psychology were being granted in clinical and counseling fields.[91] This was truly an extraordinary feat considering that only a tiny handful of psychologists (less than three hundred APA members) had even called themselves "clinical" thirty years earlier.[92]

In 1957, according to a major national study done for the JCMIH, ordinary people were relying more heavily than ever on clinical experts and formal help in order to deal with their routine personal problems: 14 percent of all those surveyed sought therapeutic assistance for a problem they defined in psychological terms.[93] In 1976, when the study was repeated, the percentage had almost doubled, to 26 percent, and approximately 30 percent reported consulting therapists in crisis situations.[94] More important, the highly conscious pursuit of personal and interpersonal meaning that the authors termed a "psychological revolution" had spread.[95] Activated first among better-off and better-educated sectors of the population during the 1950s, the revolution radiated outward and downward to become "common coin" by the 1970s.[96] Further, the reasons why people entered psychotherapy were changing. By the 1970s, "many people use a relationship with a professional as a way to explore and expand their personalities rather than as a way to undo painful or thoroughly negative feelings about themselves."[97] Using psychotherapy to cope with a "normal" dose of emotional anguish was no longer considered a prelude to psychiatric hospitalization or even a mark of mental abnormality.

The surge in psychotherapy's popularity was much more than a fad, and its consequences were much more than merely professional. The availability of new, government-supported services and opportunities for professional education and research did not, in themselves, generate a mass market for psychotherapy, though they helped immeasurably to do so. Psychotherapy for the normal gained momentum not only because of the formal expansion of government services but because it meshed easily with cultural trends that made therapeutic help appear acceptable, even inviting, to ordinary people at midcentury: the contin-

Figure 17. Group psychotherapy.

Photo: Archives of the American Psychiatric Association.

ued thinning of community ties; a vehement emphasis on the patriarchal nuclear family that put that institution under great pressure to satisfy the emotional needs of children and adults after World War II and had gone so far to challenge women's conventional gender roles; a sense of depersonalization and loss of self in huge corporate workplaces and other mass institutions.

Clinicians, for their part, encouraged people to think of psychotherapy as a perfectly appropriate way to cope with the ups and downs of modern existence. Because the logic of psychological development guaranteed each and every individual the potential for neurosis, so-called normal individuals were just as deeply affected by mental symptoms and disturbances; they were simply better at hiding them.[98] And they went further. Just as clinicians had trumpeted psychotherapy's potential to systematically aid in postwar social adjustment, so too did they (and their clients) proclaim in later years that the trend toward psychotherapy for the normal illustrated promising moves toward cultural change and development. Psychotherapy, according to one sym-

pathetic observer in the late 1960s, was a noble effort to map "the country of the soul [so that] the meaning of the long-sought civilization comes into sight and may be occupied."[99] By the early 1970s, Lawrence Kubie, a psychiatrist who had opposed the involvement of nonphysicians in diagnosis and treatment prior to World War II, and who had been involved in touchy postwar discussions about clinical psychologists practicing psychotherapy independently, was offering glowing accolades to psychotherapy's popularization.

As we make therapy more widely available, an understanding in depth of the role of the neurotic process in human development will begin to permeate our culture. In fact, this is essential for the maturation of any society. . . . Insofar as the development of the new discipline [psychotherapy] will bring insight to more people than was previously possible and infuse the work of more and more of our institutions with self-knowledge in depth, we can look to this to increase each individual's freedom to change, and his freedom to use his potential skills creatively. Ultimately this state of affairs can bring the freedom to change to an entire culture.[100]

The Humanistic Tide

During the 1950s and 1960s, humanistic experts emerged as probably the most avid proponents of a psychological theory based on normality and a therapeutic practice designed to offer liberating encounters to masses of ordinary people as well as progress to U.S. culture at large. Although the majority of individuals who identified with humanistic psychology were immersed in theoretical and clinical tasks, they viewed their work as both politically and philosophically significant. In a lecture at Yale in 1954, humanistic personality theorist Gordon Allport outlined the political challenge confronting psychological professionals: "Up to now the 'behavioral sciences,' including psychology, have not provided us with a picture of man capable of creating or living in a democracy. . . . What psychology can do is to discover whether the democratic ideal is possible."[101]

By the 1960s, humanists had moved beyond trying to prove the feasibility of democracy to pointing out the congruence between a constantly evolving democratic system and their theories of psychotherapeutic change and personality development. Personhood, the goal of psychotherapy and the subject of much psychological theory, was a pro-

cess, a fluid state of change, exchange, and ongoing renewal. The core imperatives of humanistic theory—to grow, to become, and to realize full human potential—were nothing less than democratic blueprints grafted onto the map of human subjectivity.

Although existentialism in its European version .was too gloomy and tormented for the humanists' taste (Maslow, for one, called it "high-I.Q. whimpering on a cosmic scale"), the humanists eagerly assimilated the existentialist conviction in "the total collapse of all sources of values outside the individual."[102] Refusing to surrender to European styles of unbelief, the humanists redoubled their strenuous efforts to weave inexorable democratic promise into the fabric of normal human development. "There is no place else to turn but inward, to the self, as the locus of values."[103]

The humanists called themselves a "third force," by which they meant that they were forging a path distinct from both psychoanalysis and behaviorism.[104] Although they were scattered throughout the country and institutions devoted to perpetuating their ideas were not established until the 1960s, they operated as a self-conscious tendency within the psychological professions throughout the period after 1940. For a group accustomed to describing itself, and being described by others, as a band of rebels pounding on the walls of the psychological establishment, the humanists were unusually successful in winning conventional professional rewards as well as spreading their gospel to the popular culture in the twenty-five years after 1945. Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow, two psychologists whose work is discussed briefly below, were each elected to the presidency of the APA, in 1947 and 1968, respectively, and both became gurulike celebrities (to Rogers's delight and Maslow's disgust) among fans of encounter, human potential, "new consciousness," and other variants of the 1960s counterculture.

Revolutionary bravado was a staple in the humanists' writing. Maslow, for example, compared the movement to the momentous work of Galileo, Darwin, Einstein, Freud, and Marx and called humanistic psychology "a new general comprehensive philosophy of life."[105] While some of their ideas were certainly original, others were borrowed from the very two "forces" against which humanistic psychology defined itself. Both Maslow and Rogers were quick to trace their own intellectual pedigrees to a variety of sources, including the neo-Freudianism of Karen Horney, Harry, Stack Sullivan, and Erich Fromm, the Gestalt psychology of Kurt Goldstein, the philosophy of John Dewey and Martin Buber, and the scientific method so exalted by behaviorists.

The most important common ground between the humanists and other psychological experts was the ambition to carve out "a larger jurisdiction for psychology," an expanding sphere of social authority and influence.[106] In fact, the humanists went about the task of exploring psychology's political implications rather explicitly. In the end they proposed severely narrowing democracy's subject to "the self" and pledged that practices like psychotherapy could help make that self both autonomous and mature, capable of living up to ideals of democratic thought and action.

Proving that people were capable of reasoned behavior—and not merely victims at the mercy of strong emotional currents—was a conscious, if sometimes implicit, goal for the humanists, including Rogers and Maslow. Yet they did not think of themselves as political theorists, and certainly not as political activists. Their preferred environments were academic and clinical psychology and their professional and personal identities were shaped by desires to generate scientific personality theory and help people cope with the problems of life and living.

Carl Rogers: Inherent Capacity as a Scientific Basis for Democracy

Carl Rogers was a clinical psychologist who became famous after World War II for his work in developing, and then scientifically studying, an approach to psychotherapy first termed "non-directive," and later renamed "client-centered."[107] Rogers's terminology was important; he was largely responsible for the widespread adoption of the term "client" in the mental health field. "Client" gradually replaced "patient," at least outside of psychiatry, illustrating the democratization of the therapeutic relationship and the retreat from (or sometimes even outright rejection of) the medical model in which a dependent and suffering individual relied on the kindness of an omniscient doctor.[108]

After twelve years of full-time work in a child guidance clinic (the Rochester, New York, Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children), Rogers switched to an academic career. In 1940 he moved to Ohio State University and in later years he was affiliated with the University of Chicago, the University of Wisconsin, and the Western Behavioral Sciences Institute in La Jolla, California. Toward the end of his life, Rogers founded the Center for Studies of the Person in La Jolla. Beginning in 1940, university employment facilitated Rogers's system-

atic investigation of what actually occurred during counseling and psychotherapy. He and his colleagues were the first to use and publish unedited transcriptions of audiorecorded therapeutic encounters and they earned reputations as innovative pioneers in this new field of research.[109]

The client-centered approach was based on a series of hypotheses, the most fundamental of which was an almost religious belief in the inherent human capacity for growth, psychological insight, and self-regulation. Rogers, who grew up in a very religious family and studied at the Union Theological Seminary before transferring to Columbia University Teachers College to study psychology, sometimes called it a "divine spark."[110] According to Rogers, "the individual has within himself the capacity, latent if not evident, to understand those aspects of himself and of his life which are causing him dissatisfaction, anxiety, or pain and the capacity and the tendency to reorganize himself and his relationship to life in the direction of self-actualization and maturity in such a way as to bring a greater degree of internal comfort."[111] If a nurturing interpersonal environment were achieved, in psychotherapy and elsewhere, "change and constructive personal development will invariably occur."[112]

The Rogerian conception of psychotherapy required a healthy self equipped with healthy psychological potential. "Therapy is not a matter of doing something to the individual, or of inducing him to do something about himself," Rogers wrote in one early formulation. "It is instead a matter of freeing him for normal growth and development, and removing obstacles so that he can again move forward."[113] a No longer was the therapeutic subject someone whose behavior and personality were so disordered that they needed prescriptive assistance. The therapeutic subject may have been neurotic, but he (or she) remained a "person who is competent to direct himself."[114]

The humanists' concern with normality was consistent with the overall clinical lessons of World War II. Their psychotherapeutic techniques, however, diverged sharply from those of the psychodynamic psycho-therapists who dominated the clinical professions after 1945. Simplified, the theory underlying psychodynamic practice was that experts helped individuals paralyzed and helpless in the face of unconscious fears. The clinician acted simultaneously as judge, interpreter, and healer. In contrast, the Rogerian therapist was a supportive cheerleader watching the client engage in what amounted to something like deliberate self-help. If therapists were sufficiently "permissive" (i.e., accepting and empathetic), and if they made strenuous efforts never to

interpret or even evaluate feelings or problems, then clients' internal capacity would inevitably move them toward self-understanding, and from there on to greater satisfaction and maturity. Robert Morison, an officer of the Rockefeller Foundation, was skeptical of Rogers's ideas about the therapeutic relationship and thought his detour from the medical model betrayed a "trace of fanaticism."[115]

Rogers frequently noted that the concept of internal capacity not only confirmed the logic of democratic social arrangements, but revealed the psychological roots of those arrangements. "If, as we think, the locus of responsible evaluation may be left with the individual, then we would have a psychology of personality and of therapy which leads in the direction of democracy, a psychology which would gradually redefine democracy in deeper and more basic terms."[116] Human nature and democracy, in other words, could be allies rather than enemies. In the following passage, Rogers approvingly quoted a student evaluation in order to make this point.

I have come to see that there may be a scientifically demonstrable basis for belief in the democratic way of life. . . . I cannot honestly say that I am now unalterably convinced of the infallibility of the democratic process, but I am encouraged and inclined to align myself with those who hold that each individual has within himself the capacity for self-direction and self-responsibility, hoping that the beginnings of research in areas such as client-centered therapy will lead to the unquestionable conclusion that the democratic way of life is most in harmony with the nature of man.[117]

The humanists were especially cognizant that their benign conception of human nature, and the fortuitous basis it provided for democratic ideas and behaviors, ran counter to much psychological theory and rather a lot of psychological data (especially notable were studies done under pressure of war). The bulk of twentieth-century psychological thought hypothesized a malignant psychological interior, an awful place where destructive instincts and monstrous terrors lurked, threatening to rip through the thin veneer of Western civilization. "There is no beast in man," Rogers wrote defensively in 1953. "There is only man in man. . . . We do not need to be afraid of being 'merely' homo sapiens."[118]

Rogers's famous 1956 dialogue with B. F. Skinner, leading behaviorist and author of the utopian novel Walden Two, was evidence of his deep concern not only about the political implications of various psychological theories but about the political role and direction of clinical experts and behavioral scientists themselves.[119] In his exchanges

with Rogers and elsewhere, Skinner had proposed that democratic political ideology was a historical relic. He conceded that it had perhaps been necessary and important for the political tasks facing the eighteenth century (i.e., overthrowing monarchies), but Skinner believed democratic ideology was obsolete in an era of modem science. "The so-called 'democratic philosophy' of human behavior . . . is increasingly in conflict with the application of the methods of science to human affairs."[120] Science—psychological science in particular—had revealed freedom to be mythological and social control to be both necessary and inevitable. The real question, according to Skinner, was not whether social control was good or bad, but what kinds of control would be exercised, and by whom.[121]

Rogers countered with the concept of universal, inherent capacity. He forthrightly criticized the idea that experts always knew best and worried that "the growth of knowledge in the social sciences contains within itself a powerful tendency toward social control, toward control of the many by the few."[122] Giving too much power to experts could surely lead "to social dictatorship and individual loss of personhood."[123] Rogers's apprehensions, however, revolved around people like Skinner, usually behaviorists, whose calls for power and control were most candid.

Excluded from such analysis was his own brand of helping relationship, which he claimed was based on cooperative, nonauthoritarian partnerships between "equals" or "co-workers."[124] (This failed, of course, to explain why one of the "equals" was a "therapist" while the other was a "client.") Rogers thought of his politics as a logical extension of his psychology—both were intensely egalitarian projects devoted to realizing autonomy and freedom—and regretted that more of his colleagues were not aware of the intimacy of this relationship. "There are really only a few psychologists who have contributed ideas that help to set people free," Rogers complained toward the end of his life, because "it is not in fashion to believe anything."[125]

Abraham Maslow: Democracy for the Self-Actualized Few

Abraham Maslow was an academic psychologist best known for his hierarchical theory of motivation, his description of "self-actualization," and his professional activism on behalf of humanistic psychology.[126] Initially affiliated with Brooklyn College, Maslow