Chapter Four

Valor

The Transformation of Warrior-Kings

It is a striking fact that most of the Svetambar Jains of Rajasthan consider themselves to be—like the Tirthankars, although in a different sense—transmuted warrior-kings. The Jains are identified by others, and identify themselves, as belonging to the Vaisya varna , the ancient social category of merchants and traders. Nevertheless, almost all the Osval Jains—and members of other Jain castes as well, Svetambar and Digambar—trace their descent to the Rajputs. The Rajputs are the royal and martial aristocracy of Rajasthan and are regarded as perfect exemplars of the Ksatriya varna , the ancient social category of rulers and warriors.

The Jains and Rajputs of Rajasthan have been in close contact for centuries, and their relationship is highly complex and in some ways contradictory. At one level, Rajput and Jain identities are radically opposed; at another level, they join. This chapter deals with Osval legends of their Rajput origin. These legends provide a culturally plausible account of Rajput-Jain connectedness. This account, in turn, draws deeply on images of kingship and kingly choice that are, as we have seen in previous chapters, central to the Jain view of the world. In this context, Jainism itself can be seen as a kind of origin myth for Jain social groups. To those who believe that Jainism is merely a soteriology, this will be a surprising development.

Kings Who Give Up Meat

Opposition between Rajput and Jain identity arises from the centrality to Jain life of the norm of ahimsa , nonviolence. Ahimsa , as we know, is a basic tenet of Jainism as a religious system. It is more than just a matter of religious doctrine, however, for ahimsa is also a cultural value that is embedded in many aspects of Jain life. Indeed, ahimsa is a crucial ingredient in the sense Jains have of who they are and how they differ from other communities. Jains are, or are at least supposed to be, strictly vegetarian, which differentiates them from nonvegetarian groups. But Jains also give their own distinctive modulations to vegetarianism, and this further distinguishes them from other vegetarian communities. As noted in Chapter One, observant Jains do not consume root vegetables (such as potatoes) because roots are believed to contain multitudes of souls; this is not true of vegetarian Hindu groups. Jains also contribute lavishly to Jain-sponsored animal welfare organizations and sometimes ransom goats to save them from the butcher's block. Bloodsports are naturally inconceivable for Jains. Jains avoid occupations that involve the taking of life, and the Jains themselves claim that this is why so many Jains are businessmen. Many other examples of the influence of ahimsa on Jain life could be given. Ahimsa is a value that expresses Jain piety and shapes a distinctively Jain lifestyle. It also establishes boundaries that separate Jains from other groups in Indian society, including other vegetarian groups.

The Rajputs are the opposite of all this. Jains are the most vegetarian of vegetarians; Rajputs eat meat. Jains rescue goats from the butcher; Rajputs are renowned hunters. Indeed, hunting is as emblematic of Rajput values as vegetarianism is for the Jains. Jains abstain (or are at least supposed to abstain) from alcohol, while alcohol is an important element in Rajput hospitality. Rajputs, above all, take pride in a heritage of warrior-kingship, while the Jains are deeply nonmilitary (although there have been, and are today, Jain military men). In this sense, Rajputs and Jains represent true cultural opposites.

But at the same time there is a point at which Rajput and Jain identity merge, at least from the Jain perspective. Most of the Osval Jains of Rajasthan, and other Jain groups too, claim to be descended from Rajputs who converted to Jainism and gave up Rajput customs centuries ago. This claim is frequently and vehemently made. It is true that the clan histories (of which more below) do include some accounts of

Jain clans of non-Rajput origin. And it is true, too, that it can be plausibly argued (within the assumptions of the system) that Jains, or any subgroup of Jains, sprang from "all" varna s and castes, because this in fact would be more consistent with the image of the Tirthankar as a "universal" teacher (see Nahta and Nahta 1978: 11). This, however, is not the prevailing view among ordinary men and women with whom I discussed these matters. I have been told time and again by members of Jaipur's Svetambar Jain community that the Jains are descended from Rajputs or Ksatriyas (the two words are synonymous in this context). Some individuals are reasonably well acquainted with their own clan histories; others have only vague ideas about such matters. Virtually everyone, however, takes as beyond dispute the general proposition that Jains were once Rajputs.

The claim is made by Digambars as well as Svetambars. Among Digambars, for example, the Khandelvals (the largest Digambar caste in Jaipur) are believed to be mostly descended from a Cauhan (Rajput) king of Khandela and his feudatory lords; they are said to have given up violent ways and embraced Jainism under the influence of Jinsenacarya, a famous Jain ascetic (Kaslival 1989: 64-69).[1] An alternative version (K. C. Jain 1963: 103) holds that at that time eighty-two Rajputs and two goldsmiths ruled eighty-four villages in the kingdom, and from these came the eighty-four clans of the Khandelvals. The Agravals, also prominent among Digambars, are likewise said to be of Rajput origin (Gunarthi 1987: 55-56; Singh 1990: 151-53).

On the Svetambar side, Rajput origin is claimed by both Srimals and Osvals. According to one version, the Srimals are descended from the Ksatriyas of the ancient city of Srimal, who were converted to Jainism by an acarya named Svayamprabhsuri (Srimal n.d.: 3).[2] The Osval case, our main concern here, requires extended consideration. Two separate bodies of Osval origin mythology are relevant in the present context. One, which I shall call the "Osiya legend," traces Osval origins to the town of Osiya, north of Jodhpur. The other, a group of stories that I shall call the "Khartar Gacch legends," traces the origin of Osval clans to the proselytizing activities of past acarya s of the Khartar Gacch.

Much of this material was apparently composed by Jain ascetics who, as Granoff has shown, functioned as the Jain equivalents of the caste bards and genealogists of the Rajputs (Granoff 1989b: esp. 197-98). The composers' purpose was to cement ties between their own gacch s and particular exogamous patricians (gotra s); the gacch of the

monk responsible for a clan's original entry into the Jain fold would have a perpetual right to serve the ritual, spiritual, and record-keeping needs of that clan (ibid.: 200). As K. C. Jain (1963: 99-100) has shown, inscriptional evidence demonstrates that the consecration of images was a particularly important point of ritual connection between a given gacch and particular clans. The people of a given clan would utilize acarya s of a particular gacch to perform image consecration ceremonies at their temples. Jain mentions several gaccb s, now all extinct but two, as linked in this fashion with Osval clans: the Upkes, Khartar, Maldhari, Pallival, S[?]anderak, Brhad, Añcal, and Korantak gacch s. He lists the Ganadhara Copada, Daga, Dosi, and Luniya clans as patrons of the Khartar Gacch. It seems possible that in the past there was a vast and complex network of ritual relations between clans and mendicant lineages among the Svetambar Jains of Rajasthan. If this is true, then the clan origin mythology available today and the cult of the Dadagurus may represent incomplete vestiges of what was once an arrangement of homologous and interlinked structures, an all-encompassing ritual-social order bringing the domains of spiritual and worldly "descent" together in a single system.

Osiya

Thesedays Osiya is a rather sleepy village, but legend proclaims it to have once been a large and flourishing city. Today it is an archaeological site of major importance, and it is also notable for two functioning temples.[3] One contains an image of Lord Mahavir. This temple dates from the eighth century C.E. , and according to one writer (Dhaky 1968: 312) is the oldest surviving Jain temple in western India. The other temple, but a short distance from Mahavir's, is dedicated to a goddess known as Saciya Mata. Her main importance is that she is lineage goddess (kuldevi ) to large numbers of Osval Jains. The town is accordingly an important pilgrimage center for Osvals, and the volume of pilgrimage appears to have been increasing over the last three decades (Meister 1989: 280).

What I am calling the "Osiya legend" is a myth of Osval origin that traces the caste's beginnings to ancient Osiya. This story, a variant of which I was told by the pujari s of the Saciya Mata temple at Osiya, has been retold in its various forms by Mangilal Bhutoriya in his recent Osval history (1988: 67-72), and I shall be drawing heavily on his ma-

terials in the description and analysis to follow.[4] Let me hasten to add that this analysis is not meant as an endorsement of the idea that Jain clans originated as Rajput clans. The question of how Osval clans actually arose is completely beyond the ambit of this study. Our concern here is with Osval images of their origin and identity.

The story actually begins not in Osiya itself but in the legendary ancient city of Srimal. This city is said to have been the place of origin of the Srimal caste, the other major Svetambar caste in Jaipur, but it also figures centrally in the origin of the Osvals. The roots of the tale go back to the life of Parsvanath, the twenty-third Tirthankar with whose five-kalyanak puja this book began. Parsvanath's liberation is said to have occurred in 777 B.C.E. , and of course after his departure the lineage of his disciples continued. Later came Lord Mahavir, and many of Parsvanath's followers joined Mahavir's congregation (sangh ). According to this legend, however, many stayed on in Parsvanath's own disciplic lineage, which was known as the Upkes Gacch.[5] It was Parsvanath's supposed fifth successor, an acarya of the Upkes Gacch named Svayamprabhsuri, who established the Srimal caste (above).

At this point the story shifts to the city of Srimal.[6] This city, now identified with the town of Bhinmal in Jalor District, was once a flourishing business center. At the time that Lord Mahavir walked the earth (as the tale goes), the city's monarchy was under the influence of vammargi (tantric) Brahmans. Hundreds of thousands of animals were sacrificed in religious rites, and the people were much given to meat and liquor (mas-madira ) and lewd behavior of all kinds. Buddhism and Jainism had not yet arrived, and the whole region was given over to the worship of various gods and goddesses and the appeasing of ghosts and demons.

The king of Srimal was a Ksatriya named Jaysen. He had two sons: Bhimsen and Candrasen. When the king died, Bhimsen—whowas a worshiper of Siva—succeededhim, and he changed the name of the city to Bhinmal. He, in turn, had two sons: Sri Puñj and Utpaldev (Upaldev).[7] On Bhimsen's death Sri Puñj became king, His minister's name was Suhar, and Suhar had a younger brother named Uhar. Suhar was a millionaire, and Uhar was in need of a large sum of money. At that time in Bhinmal there were three separate sections of the City reserved for men of three different levels of wealth, and Uhar apparently lacked the funds to live in a respectable area. When Uhar asked his brother for the money, his wife (in this version Uhar's wife; in other versions his

brother's wife) taunted him.[8] Stung by this, Uhar went to Utpaldev, and the two left Bhinmal together. On the road, Utpaldev bought some horses, and when at last they arrived at Delhi he gave the horses as a gift to the king there, whose name was "Sadhu". In return, the king gave him permission to establish a new kingdom on unused land.

The pair then went to Mandor, and near there, at a spot thirty miles north of Jodhpur, they established a city. Thousands of people of all four varna s came from Bhinmal to settle there. This city was later to be known as Osiya. Some say that it acquired this name from the term osla , the Marwari term for "refuge" or "shelter"; others say that it was named for the "dewy" (osili ) land upon which it was founded (Handa 1984: 8-9). Others still believe that the original name of the town was Upkespur, and that this name evolved into Osiya (Bhutoriya1988: 125).

According to the Osiya legend, it was in this city, which later became large and flourishing, that the Osval caste was established. One version of how this happened is as follows.[9] Seventy years after Lord Mahavir's liberation (or 400 years before the vikram era)[10] a mendicant named Ratnaprabhsuri came to Upkespur (that is, Osiya) with 500 ascetic followers. Ratnaprabhsuri was the sixth successor of Parsvanath (and presumably the immediate successor of Svayamprabhsuri, above), and had achieved the status of acarya fifty-two years after Mahavir's liberation. At that time, King Utpaldev and his subjects were devotees of Camunda Devi (a meat-eating Hindu goddess), tantrics (vammargi s), and completely ignorant of Jain ways. It was therefore very difficult for Jain ascetics to obtain alms, and Ratnaprabhsuri ordered his ascetic followers to leave. However, at the pleading of Camunda Devi herself he relented, and, sending 465 of his followers to Gujarat, he spent the rainy season retreat with the remaining thirty-five in Upkespur. At that time Utpaldev's companion, Uhar, was still with him and had become his state minister. One day Uhar's son was bitten by a snake and apparently died. Ratnaprabhsuri sprinkled the boy with water in which his own feet had been washed, and the boy was restored to life. All were overjoyed, and 184,000 Ksatriyas became Jains.[11] These new Jains were later to be known as Osval from the name of the city in which this happened.

In another version of the tale, one that closely resembles the version I was told by the pujari s of the Saciya Mata temple, Ratnaprabhsuri sent all 500 ascetic followers to Gujarat and stayed in Upkespur with but one disciple.[12] The disciple was at first unable to obtain alms, but he finally succeeded in getting some from an ailing householder whom he cured with medicine.[13] When he learned of this, Ratnaprabhsuri be-

came angry (probably because dan , a religious donation, should never be gotten by exchange) and prepared to leave. Then Saciya Mata (that is, Camunda Devi by a different name) appeared and begged him to teach religion to the people. He thereupon transformed a roll of wool into a snake and gave it this order: "Do what will prosper the daya dharm [Jainism]." The snake bit Utpaldev's son. King Utpaldev tried every remedy but to no avail; the prince appeared to die, and there were great lamentations in the city. The townspeople then began to take the corpse to the burning grounds. But, ordered to do so by Ratnaprabhsuri, the disciple stopped the procession and said that if the body were taken to his guru the prince's life would be restored. So they all went to the great monk and pleaded with him for the prince's life. The monk told the king that if he and his people would accept Jainism then the prince would be cured. They agreed, and by magical means the monk then called the snake. It came, removed all of the poison from the prince by sucking the bite, and disappeared. After hearing the teachings of Jainism from the Ratnaprabhsuri, the king and 125,000 Rajputs then became Jains.

In yet another version,[14] King Utpaldev's daughter, Saubhagya Devi, had married Uhar's son, Trilok Singh. Trilok Singh was bitten by a snake and the daughter was ready to become a sati[15] when he was revived by the monk's footwashings. The conversions followed.

As are other castes—Hindu and Jain—the Osval caste is divided into exogamous patrilineal clans called gotra s. The Osiya legend accounts for these by saying that there were originally eighteen Rajput clans in Osiya, and that Ratnaprabhsuri changed these into the eighteen original Osval clans (mul gotra s), which later differentiated into 498 subbranches. In his retelling of this, Bhutoriya (1988: 172-85) also lists clans founded by Ratnaprabhsuri at places other than Osiya as well as clans founded by other acarya s belonging to Ratnaprabhsuri's ascetic lineage (the Upkes Gacch). He also lists clans founded by acarya s of other ascetic lineages, but this he does not stress. As we shall see later, an emphasis on the conversions performed by acarya s of other ascetic lineages reflects a somewhat different perspective on Osval origins.

The Conversion of the Goddess

An Osval Jain acquaintance in Jaipur had been out of town for some days. When I asked him where he had been, he told me that he had gone to Osiya to worship the goddess Saciya Mata, who is his lineage

goddess (kuldevi ). And why was that? To get rid of a dos (fault, blemish), he said, and to get "peace in the family." He never did explain the exact nature of the problem, but never mind; what is of interest here is the fact that, in addition to Tirthankars and other lesser entities and deities, Jains also worship the tutelary goddesses (devi s) of patrilineages (kul s), who are believed to protect lineages and families.

The veneration of lineage goddesses is an institution shared by the Jains and Rajputs of Rajasthan, and probably by most other caste communities as well.[16] Among Jaipur's Svetambar Jains, they are found among Osvals and Srimals alike. Members of a lineage over which such a goddess presides should have their tonsure ceremonies (called mundan and done for boys) performed at her temple. Also, a bride and groom should worship the groom's lineage goddess as a postlude to marriage. In essence, a woman changes her lineage goddess at the time of her marriage, although in some families she is invited (though not required) to attend rites of worship of her natal lineage goddess. Jain families in Jaipur commonly worship their lineage goddess annually or twice yearly. This usually occurs in conjunction with either or both of the twice-yearly Navratri periods (below), but this varies greatly. There is typically a physical epicenter for a given family's or lineage's goddess consisting of a temple which is a place of family pilgrimage and the preferred locale for tonsure rites and other special observances. In the household itself the lineage goddess is commonly temporarily represented for purposes of worship by a trident, svastik , or similar emblem executed in red on a wall. In rural areas households frequently keep permanent images of their lineage goddesses (Reynell 1985: 149), but this seems to be uncommon in Jaipur. These goddesses can also be (as we have seen) propitiated in times of trouble. One might make a vow to the goddess to go to her temple to take darsan and perform puja if the trouble is alleviated, a promise that must be kept at the risk of further troubles.

It needs to be stressed that attitudes and practices relating to lineage goddesses vary enormously in Jaipur. Some families have simply lost contact with these traditions, in most cases as a result of physical or social separation from their places of origin. In other cases the widespread feeling that there is something disreputable about lineage goddesses from a Jain standpoint has corroded patterns of lineage goddess worship. When this is so, the family can go to a nonlineage goddess temple or dadabari for the tonsure rite. In the family of a Sthanakvasi

friend,the custom is to have the tonsure rite performed in a local Bhairav temple (a Hindu temple), and when he and his new wife were married they paid a postnuptual visit to a Jain nun instead of to a lineage goddess. Another friend took his bride to the Dadabari at Malpura for this purpose.

The mother of the above Sthanakvasi friend told me the following story of how her family (that is, the family into which she had married) lost their lineage goddess.[17] It seems that at some time in the remote past this family (belonging to the Bothara clan) lived in Bikaner, and once—at the time of Dasehra—theyand other families were about to worship their lineage goddesses.[18] While the food offerings were being prepared, a yati came around. He saw the preparations and angrily returned to the community hall where he was staying. There, by magical means, he drew to him all of the images of the lineage goddesses from the households in which they were kept and slapped his alms bowl over them. When the people began their puja they realized what had happened and went to the yati . He said, "If the goddess is more powerful than I am, then let her escape." He then threw the images into a well. From that time onward there have been no lineage goddesses for the Botharas (or at least in this branch of the Botharas).

Lineagegoddesses vary in their degree of territorial or social inclusiveness.[19] Saciya Mata, for example, seems to be a generalized Osval lineage goddess; her votaries are widespread, and her image can even be seen in one of the principal Svetambar temples of Ahmedabad.[20] Others are of far more local or socially parochial renown. Many, in fact, are sati s—that is, women who became deified after burning themselves alive on their husbands' funeral pyres; this is true of lineage goddesses in non-Jain castes as well. The essential idea in these instances is an amalgam of martial heroism and feminine purity. An illustrative example is provided by the story of a goddess named Satimata—despitethe name, not a sati in the narrow sense—whose temple is located in Fatehpur (in Sikar District) and who is a lineage goddess for at least some lineages belonging to the Duggar clan (of the Osvalcaste). Fatehpur, the story goes, was invested and Overrun by the Mughals. A widow and her grown daughter fled the scene and retired to a certain place where they were protected from the searching Muslims by a mysterious power. In the end they died there, but with their womanly purity intact. They then became the goddess Satimata; here the term sati carries only its primary meaning of a virtuous and chaste woman. When

Satimata is worshiped by the Duggars (which they do annually on Dasehra), she is presented with a red and white cloth; the white cloth represents the widow, who is one-half of her composite persona.

A good example of a strong, functioning lineage-goddess cult is provided by a family of Osvals I know who happen to belong to the Bhandari clan. Although I initially came into contact with this family in Jaipur, their deepest roots are in Jodhpur. Moreover, as is the case with some Jodhpur Osvals, this is a family located somewhere on the frontier between Jainism and Vaisnavism; that is, their knowledge of Jainism is rather limited, and their religious practices are somewhat more Hindu in flavor than one would expect of knowledgeable and orthoprax Jains. Others told me that this is the case of a family that probably used to be unambiguously Jain but became Vaisnavized under the influence of the local rulers whom they have served for generations.

Their lineage goddess is Durga. She is housed in a temple located on the outskirts of Jodhpur next to a temple of Parsvanath. This temple is supported by a group of Bhandari families of Jodhpur comprising about 400 individuals. When I was shown the temple, it was pointed out to me that the tiger on whom the image of Durga sits faces east rather than west, and that this indicates that she is a "vegetarian" Durga. A patriarch of the family said to me that when they were transformed from Rajputs into Bhandaris, they kept many Rajput traits: they "eat like Rajputs, "he said (though of course they are vegetarian), and they are "hospitable" like Rajputs. And, he added, they continued to worship Durga, who is the lineage goddess for many Rajputs and an inheritance from their own Rajput days.

Among this family's numerous Jaipur connections was the marriage of one of their daughters into a Jaipur Osval family. Because of the rule of clan exogamy, her husband's clan is different from hers; it is Bhurat. And his lineage goddess is different as well. His family considers their goddess to be Saciya Mata, and the Saciya Mata temple at Osiya was where his tonsure ceremony occurred.

All of this is by way of introducing the fact that the Osiya version of the origination of the Osvals is more than the story of the conversion of Rajputs into Jains; it is also about a goddess and the founding of a temple. The temple is the selfsame temple of Saciya Mata (often spelled Sacciya Mata and also known as Saciya Devi) to which reference has been made. This is the temple where many Osvals have tonsure rites performed for their male children, and of course pilgrims also visit this

temple to pay homage to the goddess after marriage ceremonies. Special observances take place here twice per year on Navratri.[21] The story of the temple is extremely important, for it restates the symbolically central theme of warrior-kingship in a special frame of reference. Saciya Mata is not the lineage goddess of all Osval Jains. Still, she is an excellent representation of an important paradigm: the taming of the goddess as a concomitant to the conversion of Rajputs into Jains.[22]

As retold by Bhutoriya (1988: 72-75), the story of Saciya Mata begins before the conversions of Utpaldev and the others. At that time (and as we have already learned) there was a temple of the goddess Camunda Devi in the town of Upkespur.[23] As is the Hindu practice, the sacrifice of goats and buffaloes was performed at this temple during the festival of Navratri. These practices are abhorrent to Jains, and so Ratnaprabhsuri put a stop to them. As a substitute for sacrificing animals, he instituted the practice of offering various sweets to the goddess. But the goddess was a meat eater and was infuriated by the deprivation of her customary sacrifices. In retribution she produced an ailment in Ratnaprabhsuri's eye. The monk, however, bore the pain with such fortitude that the goddess became fearful and asked him for forgiveness. She said that there would no longer be animal sacrifice in her temple and that thenceforth she would be known as "saccidevi ." Since then she has come to be known as Saciya Mata and what was previously the temple of Camunda at Osiya came to be known as the Saciyadevimandir .[24]

The Hindu goddess Camunda is a sacrifice-demanding, meat-eating goddess, and is in fact one of the most ferocious of the goddess's many forms, created for the purpose of destroying the infamous buffalo demon, Mahisasur. As such, her nature is in many ways identical with that of the Rajputs, who are warriors and meat eaters themselves. The link between her character and that of the Rajputs is explicit in the fact that meat-eating goddesses are commonly the lineage goddesses of the Rajputs. Clearly, therefore, the story of the transformation of the goddess is a significant element in the Osiya legend of Osval origin. The goddess Camunda is a projection of Rajput character. If this character is inimical to Jain vegetarianism—as it incontestably is—then a plausible account of how Rajputs become Jains should include an account of how a meat-eating goddess becomes transformed into a goddess who is the vegetarian functional equivalent of the meat-eating Rajput lineage goddesses. To use Meister's apt phrasing (1993: 15), the

"de-fanging" of Camunda is what the story of Saciya Mata is basically about, and it is a theme that is, as we shall shortly see, susceptible to many different elaborations.

The Tale of the Bahi Bhats

There is another version of the story of Saciya Mata. This version Bhutoriya has drawn from the poetry of the Bahi Bhats of Rajasthan. The Bahi Bhats were so named because they recorded the genealogies of the Osvals in bahis (record books)[25] Their entire lives were passed in the service of Osval patrons, and at one time there were whole villages filled with them. More recently, their traditional calling seems to have fallen into desuetude and they have taken up other occupations. In addition to keeping genealogies, they also composed poetry in praise of the families of their patrons, and before they recited their genealogies they would recite their version of the history of the Osval caste. Bhutoriya provides a Hindi translation of a Bahi Bhat account of the origin of the Osvals (1988: 109-12) that provides interesting variations on the theme of the goddess's transformation. It runs as follows:

From a sacrificial fire pit on Mt. Abu, the tale begins, there emerged four Ksatriya heroes, and from them came the Cauhan, Parmar, Parihar, and Solanki lines. A descendant in the Parmar line, Dhandhuji, was the ruler of Junagarh (near Barmer). He had two queens. The first was a daughter of Modha Singhji Solanki and the second was a daughter of Jogidasji, a Bhati (Rajput) feudal lord. The first queen bore two sons: Upaldev (Utpaldev) and Joga Kanvar. The second queen also bore two sons: Kandh Rav and Stint Rav. When Upaldev grew into young manhood he was married to a girl of the Kachvaha Ksatriya line.

One day Upaldev went out for an excursion with his friends. On the road he met a group of women water carriers who were bearing clay pots filled with water. The prince then played a thoughtless and unfortunate joke: He mocked and smashed their clay pots, spilling water over their clothing. The water carriers returned to their homes and bitterly complained about the incident. In accord with the saying, "Where the honor of daughters and sisters is not possible, in that kingdom one cannot stay," the elders of the community prepared to migrate elsewhere. Hearing of this, the king sent for them and gave his assurance that no such impropriety would occur again. Then, from the kingdom's treasury he gave them new metal pots.

Unfortunately, Upaldev and his friends had learned nothing from the incident, and they played a similar trick on the daughter of the rajpurohit (state priest). The offended priest also decided to leave the kingdom, and when the king heard of this he banished Upaldev.

Upaldev then wandered for twelve years. He rode a black mare and was accompanied by his wife and other relatives. One day his caravan of 300 vehicles came to Osiya. That night Upaldev had a dream in which his lineage goddess gave "parca "(a word commonly used in these materials to refer to a demonstration of a deity's or mendicant's powers). She said, "Don't leave this place. Start a city here." She added that the water problem (an obvious concern in the Rajasthan desert) could be solved by digging under his bed; there he would find a well that had been sealed by a certain King Sagar, and sixty paces to the north he would find ninety-nine magical pots. In the morning he awoke to discover that a saffron mark had appeared on his forehead overnight and red marks on the foreheads of all the other members of his party. He dug under the bed and found the well. But the water was salty.

The next night the lineage goddess again appeared before him in a dream. She said, "You didn't make an offering (carhava ) to the goddess (meaning herself), and that's why the water is salty. Now make the offering and the water will be sweet. And as many villages as you can encircle on your mare in a full day of riding, that will be the extent of your kingdom. First build a temple for the goddess, then your palace." He did exactly as she directed. First he built the temple, and because the goddess gave a sacca (true) parca , she was called "Saciya Mata. The temple's foundation was laid in 127 C.E. , and its construction took twelve years to complete.

After twelve years of exile had passed, Upaldev went to see his mother and father. He had married a second time in Osiya, and both wives accompanied him. He halted at the border of his father's kingdom and sent a message ahead. His father's second queen, hearing the news, began to worry that Upaldev would acquire both Junagarh and Osiya, with nothing left for her sons, and so she devised a plan to take his life. She ordered the watchmen not to allow anyone into the palace with weapons. They made Upaldev leave his weapons outside, and when the defenseless prince entered the palace temple, assassins were able to sever his head.

When Upaldev's first wife heard the news, she ignored all modesty and got down from the carriage. She took burning coals in her hand as a test of truth, and cursed Dhandhuji's second queen and her line.

Kandh Rav was later attacked by the Rathors and stripped of his kingdom (presumably as a result of the curse).

Upaldev's two wives then decided to become satis , but because the younger queen turned out to be pregnant, she could not fulfill her vow. She then went to Osiya and bore a son whose name was Bhagvan Singh. Some years later, the famed monk Ratnaprabhsuri came to Osiya. For the entire rainy season retreat he was immersed in month-long fasts. His single mendicant follower, who was not fasting, was unable to obtain alms (as in the story given above). Finally, however, he was able to obtain food from a carpenter. When he returned the next day, the carpenter put an ax in his hand with which to cut dry wood in the jungle. When Ratnaprabhsuri finished his fasting he asked why his disciple was so weak, and the disciple told the whole story. Ratnaprabhsuri grew very angry. He first decided to destroy Osiya by means of his tapobal (power of asceticism). However, at the entreaty of his disciple, and for the glorification (prabhavna ) of Jainism, he decided on a different course. He made a roll of wool into a snake and sent it to the young king, Bhagvan Singh. The king was bitten, and when the people took him to the burning grounds they were stopped by the disciple, who took them to the venerable monk. Twelve feudatory lords pleaded with Ratnaprabhsuri to restore the king to life, which he did by means of his special powers. The king himself and these twelve lords then left the worship of Siva (siv-dharm ) and became Jains. Thirteen main clans of the Osvals resulted.[26]

Now these converts had given up violence. But Saciya Mata, who after all was the lineage goddess of the king, still had to have a blood offering of two goats. Ratnaprabhsuri himself took on the burden of this problem. For three days there was no puja , and the goddess became very angry. She came to the monk and demanded the sacrificial offerings (mahabhog , as she called it). The monk responded by decreeing that there would be no more animal sacrifice, and that she would receive only two kinds of sweets (khaji and lapsi ) and coconut, and this is in fact what is offered to her at the Saciya Mata temple in Osiya today. The goddess, in response, uttered a curse. "Empty the village," she said, "in three days." Bhagvan Singh thereupon left Osiya and settled in a place called Sandva.[27]

This story is very similar to the version of the Osiya legend of Osval origin related earlier, but there are interesting differences too, and by comparing the two we can separate variant and invariant themes. For example, we note that the line of Upaldev (or, as previously, Utpaldev)

is crucial: This is the king who is the adipurus , the founding father, of the Osval line; whether it is he or his son who is converted seems not so important. We may surmise, moreover, that in the flux and flow of these stories as they were generated, told, retold, and modified by mendicants and genealogists over a period of centuries, the connection with the city of Bhinmal was, for some tellers anyway, not the essential thing. This connection was probably important for the then-extant Upkes Gacch mendicants because it puts two very important Jain castes, the Osvals and the Srimals, into a single package, which is then tied to the activities of leading ascetics of the Upkes Gacch. And it may also reflect the motives of those who, for whatever reason, wish to emphasize a special connection between Osvals and Srimals. But the essential thing is the focus on Ksatriyas or Rajputs. While it is sometimes said that those who converted to Jainism with Utpaldev came from all the varnas of Osiya (ibid.: 71), the emphasis is on Ksatriyas. As will be seen later, although some Osval clans trace their descent to non-Ksatriya converts to Jainism, the Rajput or Ksatriya convert is virtually archetypal in the tradition.

Another constant feature is the theme of miraculous intervention by a powerful ascetic. Someone is in trouble, either the minister's son or the king (or his son) himself, The theme of snakebite is a common thread, and turns out, as will be seen, to be very common in other stories belonging to the overall genre. Acarya Ratnaprabhsuri's own involvement in the creation of the problem (in some versions) seems to be a side issue. The moral issue of a Jain ascetic causing harm (or apparent harm) to a living being is, in any case, covered by the rationalization that a Jain mendicant can act in very unmendicant-like ways in the interest of the protection or propagation of Jainism. Such variations aside, the basic narrative is simple. Trouble arises. Nothing avails. Only the power of the ascetic can solve the problem, and the conversions follow.

There is one matter more, and this is of very great significance. The tale of the Bahi Bhats introduces us to the theme of the goddess's curse. As we shall soon see, this theme is important indeed to the concept of how Rajputs could become Jains. It comes to the fore in the story of the nearby Mahavir temple.

The Mahavir Temple

The other major attraction at Osiya is the eighth-century temple of Lord Mahavir. It is, in fact, only a short distance from Saciya Mata.

One of the pujaris of Saciya Mata's temple who showed me around the Mahavir temple kept referring to it simply as the "Jain temple." His implication seemed to be that Saciya Mata is a lineage goddess, whereas Lord Mahavir represents something that has actually to do with Jainism. However, the two temples are deeply interconnected, as we see from the following stories of the creation of Lord Mahavir's temple (drawn from ibid.: 72-74) which link this event to Saciya Mata and the creation of the Osval caste.

One version holds that the temple was created by the minister Uhar.[28] The image of Mahavir was made by Camunda Devi from a mixture of sand and milk, and had to be dug up from the ground. Because it was excavated prematurely (that is, before the goddess said it should have been), it had two flaws (granthi , "knots") on its chest. As we shall see later, these flaws figure importantly in other stories, and this story resembles closely the story told by the purjaris of the temple today.

According to another version—which Bhutoriya characterizes as "popular belief"—a wealthy person named Ahar was at that time trying to construct a Mahadev (Siva) temple. However, he had a big problem. As much of the temple as he built up during the day would be mysteriously torn down at night. In despair he went to Acarya Ratnaprabhsuri, who suggested that he build a temple for Lord Mahavir instead. From this point on there was no obstacle, and the temple was built. Then arose the question of the image. For some time a cow had been letting its milk fall spontaneously on the ground at a place nearby, and all were amazed by this phenomenon.[29] Upon digging at this spot, the people found an image of a Tirthankar. According to Ratnaprabhsuri, it was made of sand and milk. There were two knobs (flaws) on its chest, and the monk said that this was caused by the digging. Ratnaprabhsuri himself performed the installation ceremony of the image (while bilocationally doing the installation ceremony of another image elsewhere). The image later got the reputation of being filled with magical power.

Now, it is also said that 303 years after the establishment of this temple there was an important incident concerning the knots or flaws on the image's chest (this from ibid.: 76). It seems that some zealous laymen, thinking the two knots to be unsightly, tried to remove them. The goddess was enraged by this and created a great disturbance (updrav ) that affected the whole city. Here we recognize Saciya Mata acting in the standard role of a guardian deity to Lord Mahavir's image. In a version

of this story told to me by the Saciya Mata pujaris (below), milk and blood flowed from the image.

Disturbed by these frightening events, the community invited an acarya named Kakksuri, who was the thirteenth successor to the leadership of the Upkes Gacch, to come and quell the disturbance. He had a snatrapuja performed for the image, and in this puja the eighteen clans of the Osval caste (often referred to as the "mahajanvams " in these accounts) were the puja principals. Nine clans poured the liquids from one direction, nine clans from the other. The disturbance stopped, but because of the goddess's curse the Osvals had to leave the city. This was the great Diaspora of the Osvals. After they fled Osiya, theorizes Bhutoriya, the name "Upkesiya" must have come into currency for these people, which in time became Osvamsiya. In any case, in time the city became deserted, and so it nearly is today.[30]

The Pujaris' Tale

The pujaris of the Saciya Mata temple gave me a somewhat different version, but thematically it comes to the same thing. The tale begins in 170 C.E. when there was a marriage of a boy of Osiya to a girl from another village. When it was time to return to the boy's family (in Osiya) after the marriage ceremony, the bride said that she would neither eat nor drink without her Durga, for it seems that there was a temple for Durga in her native village. So when they brought her to her conjugal village they made a Durga temple for her, which is the present Saciya Mata temple. The goddess then came to the girl in a dream and said that an image for the temple would emerge. The mountain split and the image came out—one leg in, the other out, riding a lion.

The tale (as I paraphrase what was told to me) now turns to Raja Upaldev. He and his people all had a dream that at a certain location would be found 900,000 gold coins. They went to that spot, which is 2 kilometers from the temple, and there was a stone with a copper pot under it with the 900,000 golden coins. That's why the name of the place is "nine hundred thousand pond" (navlakhtalab ). The king then founded the temple (that is, he built it on the site of the previously existing shrine). The goddess was non-vegetarian. The population of Osiya was then 380,000.

At this point, along came Ratnaprabhsuri, and now we find ourselves on familiar ground. He went to the jungle, sat in the forest, and made

a snake out of a roll of cotton which he enlivened by means of his special powers. He then sent it to bite the king's only son. The prince sickened and died, despite the best efforts of magicians and physicians. As in the version of this tale given above, the ascetic restored the prince to life; he made another cotton snake that sucked the poison out, and the king and the people became Jains.

Now, because the king and his people had converted to Jainism, the sacrifice offered to the goddess had to stop, and this made the goddess very angry. As it happened, at this time the people were building a Vaisnava temple. These people were all Vaisnavas—the pujari says—before they become Jains.[31] Each day they would build it a little higher, and each night the angry goddess would tear down what they had built. So they went to the monk for advice, and he said, "I'll tell you tomorrow." That night he went to the goddess's temple and prayed to the goddess Durga. She said to the monk that she was angry because the people had stopped giving her meat and liquor. She said that if she was to become a Jain goddess, then the temple being built should be a Jain temple, not a Vaisnava temple. So the next day the monk told the people to build a Jain temple, which they began to do, and the construction went ahead with no further trouble.

But when the temple was finished there was no image. Now, the king's chief minister had a cow, and this cow started going to a particular spot three times daily and dropping her milk on the ground. When asked for the meaning of this, the monk Said, "I'll tell you tomorrow." He then went to the goddess at midnight. She said, "I knew you'd come to me," and then went on to say that an image was being made from milk and soil under the ground and that it would be complete in seven days. The next day the monk told this to the people. But they were impatient and dug up the image—which of course was an image of Lord Mahavir—before the seven days had elapsed. As a result, the image had a tumor on its chest. They installed the image in the temple, and the monk performed the consecration.

But then the people, unwilling to leave well enough alone, tried to remove the tumor on the image's chest by hitting it. The people who did this died on the spot, and a mixture of milk and blood flowed in a river from the wound on the image and brought various diseases to the people. Thousands died. So, as usual, the people went to the monk and asked him what to do. "I'll tell you tomorrow," he said. He went to the goddess at midnight. She was still angry from being denied her meat and liquor. He said, "You'll get sweets but not meat." She replied with

recriminations. The people had pulled the image out too soon, and had hit it—and this was the image she had made. She said that she would punish the whole village, but she also said that she would come to the aid of whoever gave her sweets and had faith in her. Because of her curse the people had to leave the village, which they did within three days. The goddess then established the following rules: 1) that after a marriage the bride and groom must come and honor her at the Osiya temple, 2) that her followers must also perform the tonsure rite at this temple, 3) that her followers should go to the temple for darsan , and 4) that they must worship her as their kuldevi (lineage goddess). Because of the curse, no Osvals can live in Osiya (or at least not, the pujari added, "with families").

Lineage Goddesses

We see, then, that the Osiya legend is not a single tale but a whole complex of tales. There are many versions, refracted through the sensibilities of various tellers, but thematically they all show a remarkable consistency. They center on three basic matters: the conversion of Rajputs into Jains; the taming (or Jainizing) of a meat-eating, sometimes angry, and curse-delivering goddess; and the relationship between the Osval caste and the image of Lord Mahavir. This latter relationship is a complex one: Osvals venerate the image, but are cursed to stay at a distance. And this complexity, in turn, echoes an ambivalence in the goddess's own character. She is a vegetarian lineage goddess for Jains, but she is nonetheless never quite tamed.

The physical juxtaposition of the two temples—Saciya Mata's and Lord Mahavir's—is emblematic of these issues. How is it possible, we may ask, for Rajputs to become Jains? At the level of the logic of ritual symbolism this can be transmuted into another question, namely, how is it possible to bring these two physical structures into a viable relationship? The answer seems to be, in part, that a meat-eating goddess must become vegetarian, and must also become the servant and protector of Lord Mahavir. This formulation is of particular interest because not only does it reach deeply into the heart of Osval identity, but it also provides a wider Indic context for this identity. This is because the goddess is an Indic figure, not a specifically Jain figure. Camunda, who is the original goddess whose nature is transformed, is a manifestation of the transregional Hindu goddess in her warlike form. According to the stories we have examined, she was the lineage goddess of Utpaldev. She

then became a lineage goddess for Osval Jains. This suggests the need for a closer examination of the phenomenon of lineage goddesses among the Rajputs.

The lineage goddess complex is, in fact, central to Rajput cultural and social life, and we are fortunate indeed that this complex has recently been subjected to a searching ethnographic description and analysis by Lindsey Harlan (1992). What follows is based on her account.

Among the Rajputs, lineage goddesses are associated with patrilineages (kuls ) or their subdivisions (which, though branches of kuls , are frequently confused with kuls ). Kuls , in turn, are considered segments of the three great clans (vams ) of the Rajputs, the sun, moon, and fire lines. The kuls are traced to founding ancestors who, as Harlan notes, "typically left a homeland ruled by an older male relative or conquered by a foreign invader" (ibid.: 27). The goddesses are seen as protectresses of the lineages with which they are associated, and this function is typically demonstrated when the goddess in question manifests herself at critical junctures in order to come to the aid of Rajputs who are in danger of some kind. "In most cases," Harlan writes, "she reveals herself to their leader and inspires him to surmount whatever problems he and his followers face. Often she first manifests herself in an animal form. Afterward she helps him establish a kingdom, at which point he and his relatives become the founders of a kinship branch (kul or shakh ) with a discrete political identity" (ibid.: 32). Subsequently she continues to manifest herself at times of crisis to render aid. We have already encountered, in a Jain context, the theme of aid in kingdom establishment in the tale of the Bahi Bhats.

The theme of protection is fundamental to the entire ritual and mythical complex surrounding lineage goddesses among the Rajputs. The goddess possesses power, sakti , which she uses on behalf of the group over whom she exercises guardianship. In Harlan's materials the myths concerning the first manifestations and miraculous interventions of lineage goddesses involve such protective acts as saving endangered princes (and thus the lineage), reviving exhausted and wounded warriors on the battlefield, and aiding in conquests and in the establishment of kingdoms.

Kingship and the battlefield are tightly intertwined in the imagery surrounding lineage goddesses. These goddesses are, above all, protectresses on the battlefield. Rajput men are warriors; they fight for glory and to expand their kingdoms. The lineage goddess appears at crucial

moments to aid them in this endeavor. She also protects the kingdom through the figure of the king. The king is her chief devotee, and by protecting him she protects the kingdom as a whole. Thus, she is not only an embodiment of the identity of the lineage, but her worship also legitimizes the king's rule.

The public buffalo sacrifice occurring on Navratri is, as Harlan shows (ibid.: 61-63), the perfect exemplification of this principle. The lineage goddess is identified with the Sanskritic goddess Durga, the slayer of the buffalo demon Mahisasur. As the sacrificer, the king is identified with the goddess. But he is also identified with the sacrificial victim, who is himself a king. "Thus," says Harlan, "the blood he offers is also his own. The demon Mahish, liberated by death from his demonic buffalo form, becomes the Goddess's foremost devotee. The king, also represented as the kuldevi 's foremost devotee, offers her his death to assure her victory over the enemies of his kingdom" (ibid.: 63). These ideas resonate deeply with the image of the king-warrior who sheds his blood in battle; his blood "nourishes the kuldevi who protects the kul and the kingdom" (ibid.).

Saciya Mata is also closely identified with Durga. Before her transformation she was Camunda, who is one of Durga's forms. The pujari of the Saciya Mata temple told me that the "form" of Saciya Mata is Mardini Durga, and Handa (1984: 16) concurs that Saciya is a manifestation of Durga Mahisamardini (that is, the goddess as "Destroyer of the Buffalo Demon"). It is of interest to note that R. C. Agrawala (n.d.: 19- 20) reports that images of Mahisamardini are actually still being worshiped in some Jain temples in western India. The pujari of the temple added to the above statement that just as the Rajputs have their Durga, the Osvals have Saciya. He is, of course, exactly right. Saciya is, in effect, a vegetarian Durga, suitable for Osvals. She is a generalized Rajput lineage goddess, sanitized in such a way that she becomes an appropriate lineage goddess for those who once were Rajput but have now become Jains.

It should be noted that the vegetarianization of a meat-eating goddess is not a purely Jain phenomenon, for there is a prominent Hindu example as well. The famed Hindu goddess Vaisno Devi was in all likelihood once a meat-eating goddess herself, who became "tamed" in accord with values deriving from the Hindu Vaisnavas.[32] Her name derives from the term Vaisnava , and the Vaisnava tradition is strongly vegetarian; indeed, the term Vaisnava can mean, simply, "vegetarian."

Vaisno Devi thus appears to be another transmuted goddess, tamed in submission to the vegetarian imperative of a non-Jain ritual culture.

Ambivalent Goddesses

The Hindu goddess—that is, the goddess of the wider South Asian religious' world outside the ambit of Jainism in the strict sense—is a very complex figure. Many analysts have noted an apparent conflict between What seem to be two very different, even contradictory, sides of her nature. When she takes the form of such manifestations as Laksmi she embodies fertility, prosperity, and well-being. As Kali and in other similarly fearsome or martial forms, however, she is associated with bloodshed and death. As David Kinsley (1975) has pointed out, this is not necessarily a contradiction. When seen in the context of wider Hindu views about the nature of the cosmos, prosperity is destruction, and birth is death. It seems possible that these transformations of the goddess's character have something to do with marriage (see Babb 1975: 217-29; but for a contrary view see Erndl 1993). Her more combative forms are often represented as unmarried, or at least marriage is unstressed, whereas her more peaceful manifestations seem to be associated with the married state.

These issues emerge in an extremely interesting way in Harlan's materials. The lineage goddess has two sides or facets among the Rajputs. For men, she is a protectress of the lineage and the kingdom. For women, on the other hand, she is primarily a protector of the household. These two functions are associated with radically different images of the goddess: unmarried versus married. As household protectress she frequently appears to women in dreams or visions, and when she does she appears in the form of a "lovely suhagin ," a married woman (Harlan 1992: 65). The battlefield protectress, often appearing in animal form, is directly associated with unmarried Durga, "whose very power derives from her status as a virgin unrestrained by male control" (ibid.: 71). As household protectress she is linked with the ideal of the pativrat , the dutiful wife; here her protective function is wifely and maternal. Indeed, to be a pativrat is to emulate the lineage goddess who is the archetypal protectress that an ideal wife should be.[33] Moreover, in the worship of the lineage goddess in her domestic manifestation, which is primarily a women's activity, fasting replaces blood sacrifice as the central ritual motif (ibid.: 86-88).[34]

The Rajput lineage goddess, moreover, is not merely an emblem of

the identity of the group with which she is linked; she is an embodiment of that identity in a way that seems to involve a linkage of substance. As Harlan points out, fluid imagery is very important in this context. She is associated with the blood her warriors shed on the battlefield; when the king or warrior dies, his death is a sacrifice to her that "nourishes" (ibid.: 62) her. But other myths portray her as a milk-giver (ibid.: 55-56), an image that seems to come to the fore in the domestic contexts of her worship (ibid.: 69-70). In these fluid transactions the lineage goddess emerges as custodian not merely of a lineage's power and renown but of its very substance. In this connection, it is surely significant that, according to one version of the tale, when the people of Osiya undertook their ill-advised project of repairing the Mahavir image, the goddess's anger is manifested as a flow from the image of a lethal mixture of milk and blood, two powerful symbols seemingly associated with the essential nature of any lineage goddess, Rajput or Jain.

From the standpoint of the goddess, when Rajputs become Jains the issue is sacrifice. And what is at issue is not merely what the goddess eats, although that is an important aspect of the matter. More fundamentally, and as we see in Harlan's material, the very symbolism of the sacrifice itself is central to the notion of who Rajputs are. Rajputs are those who offer themselves on the battlefield as the goddess's sacrificial victims. The Navratri buffalo sacrifice resonates with this idea. Thus, when Rajputs become Jains the sacrifice must go. As in the Rajput myths—myths that associate the lineage goddess with a crucial event in the formation of a group and the establishment of its identity—the transformation of Camunda into Saciya Mata is associated with the formation of the Osval caste. Crucial to this event is Camunda's giving up of sacrificial victims. She becomes vegetarian, in parallel with the transformation of meat-eating Rajputs into Jains, which is central to the myth of Saciya Mata's temple.

However, in this transformation she does not lose all of her former functions or character. She remains a protectress, but she also seems to retain a certain vindictiveness. In Harlan's materials the lineage goddess can be punitive (ibid.: 68-69), punishing her devotees for their own good. The punishment is frequently imaged as a deprivation of fluids; cows dry up or her victims' bodies are dessicated by fever. Often she does this "because her worship has been neglected in some essential way. She warns that unless her worship is performed properly, various undesirable consequences will ensue" (ibid.). We see the same tendency

in the myths of Saciya Mata's curse. In the tale of the Bahi Bhats her anger arises from the omission of an essential element of her ritual culture, namely animal sacrifice. In the myths of the Mahavir temple a Jainization of her bad temper has occurred; here her anger is not inspired by neglect of her ritual needs but by mistreatment of Mahavir's image.

It is of interest that, in an apparent inversion of the Rajput imagery, in the pujari s' tale Saciya Mata's punishment of the Osvals is manifested as too much fluid, not too little. This rather surprising reversal may have the function of preserving—within the context of an encompassing idea of the goddess's punitive inclinations—a clear distinction between Jain and Rajput goddesses.

But we must note, finally, that in a sense the Jain version of the Rajput lineage goddess is not really "transformed" at all, because even the Rajput lineage goddess has a "Jain" side to her character—that is, there is a side to her character of which Jains can approve. We see this in the distinction between the Rajput lineage goddess in her martial and pativrat forms—the lineage goddess of the mardana (men's quarters) versus the lineage goddess of the zanana (women's quarters) respectively. The Rajput lineage goddess does indeed possess an unwarrior-like form, which is her domestic manifestation. And it is surely significant that when the domestic lineage goddess is stressed (as is the case in women's worship), not only does the Navratri buffalo sacrifice recede into the background, but on the all-important occasion of Navratri the votive fast (vrat ) moves to the fore (ibid.: 88).

The imagery of the domestication of Saciya Mata, I suggest, can be seen as an assertion of the domestic subtradition of Rajput lineage goddess worship, a subtradition with an ascetic bias. In a tale of Rajputs becoming Jains, it makes sense for sacrifice to be pushed aside, allowing asceticism to assume the central role in religious practice. Saciya Mata becomes the servant and protector of ascetic Lord Mahavir, which is emblematic of the fact that the fast, not blood sacrifice, has become the defining ritual act.

Khartar Gacch Legends

Because of its putative time-depth, the Osiya legend might be considered the most "inclusive" account of Osval origin. From the perspective of Jaipur, however, the Osiya myth seems to recede into a nebulous background. In this city, the dominant influence is the Khartar

Gacch, and the most relevant Osval origin mythology emphasizes the role of this mendicant lineage in the creation of Osval clans. I will refer to this body of material as the Khartar Gacch legends. Because the Khartar Gacch did not come into existence until the eleventh century C.E. , the putative time frame of the Khartar Gacch legends is much later than that of the Osiya legend.

Lest we lose the thread of our overall argument, it must be emphasized that the Khartar Gacch legends stress, as does the Osiya legend, the claim of Rajput/Ksatriya origin for most Osval clans. In a history of the Osval caste that adopts the Khartar Gacch perspective (Bhansali 1982; see chart on pp. 217-22), out of the eighty-one major clans listed, a total of sixty-five are (by my reckoning) traced to Rajput/Ksatriya clans or lineages.[35] Six are held to be of Mahesvari (a business caste similar to the Osvals) origin, but the Mahesvaris themselves are said to have been Ksatriyas originally. The remainder (including two clans of Brahman origin) can be regarded as special cases that do not disconfirm the main trend.

These accounts may be considered to be expressions of a coherent general theory about the origin of the community of Osval Jains. This is a theory that was shared by most of those with whom I discussed these matters in Jaipur. Some were hazy about the specifics, but the general view that Osval clans were created when Rajputs were converted to Jainism by distinguished ascetics—mostly Khartar Gacch ascetics—was quite widespread (see Figure 12 for an illustration of this belief). The Khartar Gacch legends themselves are less focused on the origin of the Osval caste as a whole than on the separate origins of Osval clans. As articulated to me by Jaipur respondents, the underlying theory holds that the Osval clans were created by Jain monks. These monks then encouraged their converts to marry only their co-religionists. In this way, the exogamous clans became knit into the encompassing Osval caste.

In what follows I draw heavily on two volumes that were placed in my hands by knowledgeable Jains in Jaipur. One is a history of the Osvals (cited above) authored by Sohanraj Bhansali (Bhansali 1982). The other is a short anthology of materials on jatis (castes) and clans putatively converted by Khartar Gacch monks (Nahta and Nahta 1978). Each of these books brings together large amounts of material gleaned from traditional genealogists, and together they are a rich source of material on Osval origins from the Khartar Gacch point of view.

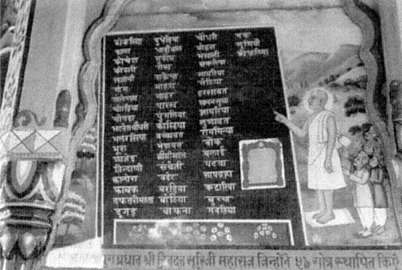

Figure 12.

Jindattsuri pointing to the names of clans created by him. Picture

on the wall of the dadabari at Ajmer.

The Quality of Miracles

A survey of these tales of conversion and clan formation reveals that thematically they are very much like the Osiya legend; the major differences are in the details. As in the Osiya legends, the theme of an ascetic's miraculous power is central. The convert-to-be, usually a king of some kind, finds himself in serious difficulty. A Jain mendicant overcomes the difficulty in a miraculous fashion, and the conversions follow.[36] The following examples will provide an idea of the range of the difficulties and miraculous interventions involved in these tales.

The difficulty is often the bite of a snake. For instance (this from Bhansali 1982: 67-72), the Katariya (or Ratanpura) clan came into being when a Cauhan (Rajput) king was bitten while resting under a banyan tree. Dadaguru Jindattsuri,[37] who just happened to be nearby, cured the king by sprinkling mantrit jal (mantra -charged water). The king offered him wealth, but Jindattsuri explained that mendicants cannot possess wealth. Jindattsuri then spent the rainy season retreat in the king's city (Ratanpur). The king came under the influence of his teachings, with the result that he and his family became Jains.

The miraculous cure of an illness is also a major theme. A good example is the story of the Bavela clan (ibid.: 117). The Cauhan king of Bavela suffered from leprosy. As in all these tales, no cure could be found. However, in 1314 C.E. , Sri Jinkusalsuri (the third Dadaguru) came to the kingdom and told the king of a remedy that had originated with the goddess Cakersvari (a Jain goddess). The remedy was tried, and in seven days the king recovered. He then converted to Jainism, and his descendants became the Bavela clan.

Another example of a clan originating with the cure of an illness is the Bhansali clan (ibid.: 149-50). This is in fact one of the most illustrious of the Osval clans. In the tenth to eleventh century a Bhati (Rajput) king named Sagar ruled in what is now the famous pilgrimage town of Lodrava (near Jaisalmer). He had eleven sons, of whom eight had died of epilepsy. One day, Acarya Jinesvarsuri[38] came to the town. The king and queen went to him and pleaded for him to do something to save their remaining three sons. Jinesvarsuri said all would be well if they gave the kingdom to one son and allowed the other two to become Jains. The king agreed, and Jinesvarsuri initiated the princes in a bhandsal (a barn or storage building), which is how the clan got its name.

Considering the warlike nature of the Rajputs, it is hardly surprising that victory and defeat in battle are issues on which these conversion tales sometimes hinge. An example is the story of the origin of the Kankariya clan (ibid.: 1982: 72-74). It so happens that in 1085 one Bhimsen, the Ksatriya lord of Kankaravat village, was summoned by the king of Cittaur. He refused to obey, and the king of Cittaur sent an army to fetch him. Bhimsen took the "shelter" (saran ) of Acarya Jinvallabhsuri,[39] who happened to be visiting the village at that time. The monk said that he would help if Bhimsen became his sravak (lay Jain). After Bhimsen had accepted Jainism, Jinvallabhsuri had a large quantity of pebbles brought. He rendered them mantrit (that is, infused them with the power of a mantra ), and, in accord with his instructions, when the Cittaur army came they were met with a shower of these pebbles. The invaders panicked and fled. The clan got its name because of the role of these pebbles (kankar ) in its founding.

The Khimsara clan began as a result of defeat in battle (ibid.: 76-78). In a place called Khimsar lived a Cauhan Rajput named Khimji. One day, enemy Bhatis plundered his camels, cows, and other wealth. With some of his kinsmen he pursued the thieves, fought them, and was

defeated. While returning to his village he met Acarya Jinvallabhsuri and told him the sad story. The monk said that if Khimji would give up liquor, meat, and violent ways, then all would be well. Khimji and his companions accepted. The monk then repeated the namaskarmantra according to a special method designed to subjugate enemies and then gave his blessing. Because of the influence of the mantra the mental state of Khimji's enemies changed; they begged for mercy and returned all their plunder. This story further tells of how these converts maintained marriage relations with Rajputs for three generations. But in the end, troubled by "derision" (whose is not clear), Bhimji (a descendant of Khimji) brought the problem before Jindattsuri when he happened to visit the village. The monk imparted his teachings, and then joined this clan to the Osval jati (caste). They then began to marry within the Osval caste.

The Gang clan (ibid.: 80-82) is another example of a clan created because of an ascetic's intervention in battle. Narayansingh was the Parmar (Rajput) ruler of Mohipur. There he was besieged by Cauhans. The Parmars began to run low on resources, and things looked grim. Narayansingh's son, however, reported that Acarya Jincandrasuri "Manidhari" was nearby, and suggested that this very powerful ascetic might help them out of their difficulty. The son disguised himself as a Brahman astrologer and sneaked through the enemy lines and came to the monk. The monk taught him the sravakdharm (the path of the lay Jain), and, on the son's promise that he would accept Jainism, repeated a powerful stotra (hymn of praise) for getting rid of disturbances. The goddess of victory appeared with a powerful horse. On this horse the son rode back to Mohipur. Because of the influence of the stotra , when the enemy army saw him they thought they were seeing a vast army that was coming to aid the besieged Parmars. They fled, and in the end all sixteen of the king's sons became Jains, which is the origin of the sixteen subbranches of this clan.

Some conversions result from a lack of male issue. The Bhandari clan (ibid.: 163-64) is an example. In the tenth to eleventh century there was a Cauhan ruler of Nadol village (in Pali district) named Rav Lakhan. He had no sons. One day, Acarya Yasobhadrasuri[40] came to the village. The king told him about his trouble and asked for a blessing. The monk said that sons would come, but that one of them would have to be made into "my sravak ." The king's twelfth son became a Jain, and because he served as the kingdom's treasurer (that is, keeper of the bhandar ) the

clan became known as Bhandari. A descendant of this son came to Jodhpur and settled in 1436. Previously this family had been known as "jainicauhanksatriya ," which means that they were Jains who were still Rajputs. At this point they became Osval Jains as a result of the teachings of a Khartar Gacch acarya named Bhadrasuri.

Conversion and Supernatural Beings

In parallel with a similar pattern that we have seen already in the story of Saciya Mata, in these tales the work of conversion is sometimes associated with the "Jainizing" or taming of non-Jain supernaturals. As Granoff points out (1989b: 201, 206), the ascetic in these tales often works his conversion miracle through the agency of a clan deity, usually a goddess, a theme that is certainly present in the Osiya materials surveyed earlier. "In these stories," Granoff points out, "monks are often powerful because they can command a goddess to do their bidding and aid their devotees or potential devotees" (ibid.: 201-2).[41] Granoff's survey of clan histories discloses another common pattern, that of the vyantar who is in fact a deceased kinsperson and who has come back to trouble his or her former relatives; the malignant spirit is then pacified by the monk and becomes a lineage deity (ibid.: 211). Most of these ideas are also present in the Osval materials I have surveyed.

For example, converts-to-be sometimes suffer from demonic possession. An alternative story about the Bhansali clan (this one from Nahta and Nahta 1978: 36) again focuses on King Sagar. One day a brahm raksas (a kind of demon belonging—the demon himself says in the story—to the "vyantar jati ") afflicted his mother.[42] Nothing could induce it to leave her. Finally, in the year 1139, Acarya Jindattsuri arrived in Lodrava and was asked to remove the demon. When he ordered it to go, it responded by saying, "The king was my enemy in a previous birth; I taught him about nonviolence, but this wicked devotee of the goddess wouldn't accept it and killed me. After I died I became a brahm raksas and I have come to destroy his family in revenge." The monk taught the demon Jain doctrine and made his vengeful feelings subside. The demon then left the mother, and Sagar became a Jain in the bhandsal as before.

In fact, the Bhansali clan seems to have had special problems with vengeful supernatural beings. According to another story (Bhansali

1982: 158-59; see also Granoff 1989b: 214-15), there was once an inhabitant of Patan named Ambar who hated the Khartar Gacch. When Jindattsuri's disciple came to Ambar's house to obtain food and water for the guru's first meal after a fast, Ambar tried to kill Jindattsuri by providing poisoned water. At Jindattsuri's instructions, a Bhansali layman, who happened to be in the community hall at the time, mounted a hungry and thirsty camel to fetch a special ring that would remove the poison. When the ring was brought and dipped in the water, the influence of the poison abated. Then this entire unfortunate matter became known throughout the city, and the king summoned Ambar, who admitted his guilt. The king gave the order for Ambar's execution, but Jindattsuri had the order cancelled. After that, Ambar began to be called "hatyara " (murderer), and upon his death he became a vyantar and began to create various kinds of disturbances (updravs ).[43] He vowed that he would not become peaceful until the Bhansali line was destroyed. In the end, Jindattsuri thwarted this vyantar by waving his ogha (broom) over the Bhansali family ("parivar ," but apparently referring here to the entire Bhansali clan). This is how the Bhansalis acquired their reputation of being second to none in their devotion to gurus (guru bhakti , and referring specifically to devotion to the Dadagurus).

An example of the involvement of a goddess in the origin of a clan is provided by the story of the Ranka-Vanka clan (Nahta and Nahta 1978: 38-9). The two protagonists, Ranka and Vanka, were descended from Gaud Ksatriyas, who had migrated from Saurashtra; they lived in a village near Pali where they were farmers. One day Acarya Jinvallabhsuri came and declared that Ranka and Vanka were destined to have an encounter with a snake within a month, and that they should refrain from working in the fields. Despite the warning they continued to go to the fields, when finally, as they were returning one evening, they stepped on the tail of a snake. The angry snake pursued them, and they had to take refuge in a temple of the goddess Candika (a meat-eating Hindu goddess) where they slept that night. In the morning, they saw the snake still lingering near the temple. They then began to praise the goddess in hopes of eliciting her aid. The goddess said, "Because of the sadguru 's (Jinvallabhsuri's) teaching I have given up meat eating and the like, and you people must give up farming and become the 'true lay Jains' (sacce sravaks ) of Jinvallabhsuri." She called off the snake, told them that they would acquire svarnsiddhi (the ability to make money), and sent them home. Later, Acarya Jindattsuri visited that place and

Ranka and Vanka began to attend his sermons. They were "influenced," became pious lay Jains, and later prospered greatly.

The Jain goddess Padmavati is important to the story of the origin of the Phophliya clan (ibid.: 49-50). The story begins with King Bohitth of Devalvada, who founded the Bothara clan (a very well known Osval clan) after being converted to Jainism by Jindattsuri. At the time of his conversion, his eldest son, whose name was Karn, remained a non-Jain and succeeded his father to the throne. Karn, in his turn, had four sons. One day he was returning from a successful plundering expedition when he was attacked and killed. His queen then took her sons to her father's place at Khednagar. One night the goddess Padmavati appeared to her in a dream, and said, "Tomorrow because of the coming to fruition of your powerful merit, Sri Jinesvarsuriji Maharaj will come here; you should go to him and accept Jainism, and you will obtain every kind of happiness." The four sons all became Jains. They made an immense amount of money in business, and were assiduous in doing the puja of the Tirthankar. At the instruction of Jinesvarsuri, they sponsored a pilgrimage to Satrunjaya, and while on the way they distributed rings and platters full of betel nuts (pungiphal ) to the other pilgrims. For this reason the eldest son's descendants become known as the Phophliya clan.

Even the Hindu god Siva was once used by a Jain monk as an instrument of conversion (ibid.: 42). It seems that the Pamar king of Ambagarh, whose name was Borar, wanted to see Siva in his real form, but was never successful.[44] When he heard about Acarya Jindattsuri he went to him and asked if he could arrange such an encounter. The great monk said that he would arrange the vision, but only if the king agreed to do whatever Siva instructed him to do. The king agreed, and went with the monk to a Siva temple. Standing before the linga (the phallic representation of Siva), the monk concentrated the king's vision, and amidst a cloud of smoke trident-bearing Siva himself appeared. Siva said, "O King, ask, ask (for a boon)!" The king said, "O Lord, if you are pleased, then give me moks (liberation)." Siva said, "That, I'm afraid, I don't have in my possession. If there's anything else you want, then say so, and I'll give it to you, but if you desire eternal nirvan , then you must do what this Guru Maharaj says." After the god left, the king worshiped Jindattsuri's feet and asked how to obtain liberation. The monk imparted the teachings of Jainism, and the king accepted Jainism in 1058. His descendants are the clan called Borar, so named for their royal ancestor.

Warrior-Kings Transformed

If one looks over the conversion stories as a group, it is possible to see that the interventions by Jain ascetics often have certain interesting common features. The cure or rescue is usually accomplished by means of the ascetic's personal supernormal power, which is often mediated by substances or deities. However, and importantly, such magical power is accompanied by something else. It is not enough for a convert-to-be to be overawed by an ascetic's miraculous power; a vital ingredient is a transformation in the convert-to-he's outlook. Whether or not it is made explicit in the narrative, the assumption is that this is accomplished by means of the ascetic's updes , his teachings. The ascetic is usually said to "awaken" (pratibodh dena ) the convert. The convert thereby becomes "influenced" (prabhavit ) by the ascetic's teachings. He then comes to "accept" (angikar karna ) the Jain dharm (Jainism).