"They, Verna and Billy"

Verna Arvey would be known only as a minor figure in Los Angeles's pre-émigré world of music and dance were it not for her long association with William Grant Still. She learned of Still's work as early as the mid-1920s but met him only in 1930, when she came to his attention as a lively young musician and writer with commitments to both the "new" and the New Negro movement that in many ways paralleled his own. Her interest in musical modernism emerges clearly in January 1926, in a review for her school newspaper of a concert that included music by Henry Cowell.[1] As will be seen, Cowell encouraged her career in several significant ways, as he did that of many others, including Still. Arvey's awareness of Still and the Harlem Renaissance (elsewhere the New Negro movement) came through Harold Bruce Forsythe, an older contemporary, longtime friend, and inspired correspondent since Manual Arts High School days. Forsythe's developing advocacy of an eclectic modernism influenced her strongly.[2]

Arvey followed Forsythe's model in placing her skills in the service of Still's career. She began soon after Still's arrival in Los Angeles in 1934 by serving as his secretary, rehearsal pianist, publicist, and sometime performer of his music. After the break with Forsythe, which probably occurred in late 1935 or early 1936, she committed herself much more fully to Still, abandoning her own aspirations as a recitalist and turning down an offer of a teaching position in New York City. Thereafter she displaced Forsythe as Still's collaborator and friend, eventually becom-

Figure 10.

Verna Arvey.

Courtesy of William Grant Still Music.

ing his librettist, editor, and archivist as well as, from 1939, his spouse. Arvey's early bohemian persona was so fully subsumed in her commitment to Still that one recent commentator, finding it virtually impossible to separate out her contribution, wrote that "in many respects, they, Verna and Billy, were William Grant Still."[3]

The picture of Arvey in her teens and early twenties that emerges from her scrapbooks, five-year diaries, and other memorabilia is of someone almost unimaginably different from the later images. In particular, the forbidding self-image projected by In One Lifetime (1984), Arvey's late personal memoir/biography of Still, separates her from this early identity; it serves, if anything, to intensify the urgency of the questions about the nature and extent of her influence on Still.[4] These questions tend to place a heavy burden on Arvey, in some cases diverting attention away from the difficult aesthetic issues that Still faced, even tending to shift responsibility for decisions that were clearly his. For example, Arvey's role in Still's increasing isolation after 1939 is challenged, and even Still's aesthetic approach indirectly questioned by the remarks of two of his acquaintances, who said in separate interviews that Arvey had "protected" Still from his proper source of inspiration, the

everyday lives of African Americans.[5] The quality of Arvey's librettos for all of Still's operas after Troubled Island has been directly attacked, perhaps with more justification, by Donald Dorr.[6] Beyond Arvey's private statement that she was the author of an anticommunist speech delivered by Still in 1951, questions have arisen about the extent of her influence as the typist or editor or perhaps even the writer of many of his letters, articles, and speeches, and as the "manager" of his domestic and professional life. It becomes important, then, to sort out something of Arvey's identity and to explore what her contributions to Still's career were.

Arvey was born in Los Angeles in 1910 of working-class Jewish parents, both of whom had emigrated as children from Russia to Chicago. She was the second of three children, the older of two sisters. She skipped two grades in elementary school, then was made to sit out a year to rest her eyes. That year she got interested in practicing the piano, learned to sight read music printed in old issues of the Etude, and worked as a volunteer reader in a kindergarten. Although the family identified themselves as Jewish, they were not observant. They were enthusiastic members of a spiritualist church while Verna was in middle school and high school. She served as the congregation's pianist, playing hymns and becoming thoroughly disillusioned as she observed some obvious fakery. Remembering this experience, she was disappointed to learn of Still's deep interest in the occult. Later, however, she accepted the integrity of his purpose and participated with him willingly in an informal spiritualist circle.[7]

An inspiring middle school teacher helped Arvey become fluent in Spanish and stimulated her interest in Hispanic culture; later on she won a prize in a citywide high school competition for her skill. Her early desire to pursue journalism as a career led her to Manual Arts High School. There her extracurricular activities included Girls' Self-Government, Press Club, the debate squad, and a stint as feature writer for the Manual Arts High School Weekly: "I went out on my own and interviewed a lot of musical celebrities for the paper. In consequence, ours was one of the few high school papers carrying interviews with such artists as Joseph Lhevinne, Tito Schipa, Lucrezia Bori, Lawrence Tibbett (one of our own graduates) and others."[8] Interviews remained a favored journalistic genre for her long after Manual Arts.

When Arvey graduated from high school in 1926, she was four months beyond her sixteenth birthday. In the same year, her parents divorced

and her mother became a chiropractor. Her older brother was already an undergraduate at the University of California at Los Angeles, studying zoology, but the teacher training course in music offered there did not appeal to her. She aspired, according to a graduation brochure, to attend a "musical conservatory or University of Southern California—music course."[9] She continued her piano study for several years and developed a studio of her own, but her hopes and plans to go to college or to a conservatory never materialized.

Arvey's scrapbooks, assembled between about 1922 on, reflect her eclecticism, for they include her writings on film, theater, and dance as well as music.[10] They also reveal her efforts to learn and write about concert music by composers of Latin American and African American heritage. Her ideas about the use of music in movies developed soon after she left high school. Finding it impossible to gain the access to the studios she sought, she asked for help from her paternal uncle, Jake Arvey, whose name occasionally surfaces in books on machine politics in Chicago, where he was already a prominent alderman. Uncle Jake's connections with the distribution side of the movie business were no help.[11] Her interest in music for the movies continued, during this period of transition from silent to sound film, and eventually resulted in what is apparently the first "serious" magazine article about movie music, published in the Etude in January 1931.[12] That article—the first of many for that magazine—reflects her journalistic approach, which continued to depend on interviewing prominent people and reporting their remarks. For it, she queried the heads of the music departments at RKO, MGM, Fox, and Universal, respectively, as well as Los Angeleno Lawrence Tibbett.[13]

After leaving high school, Arvey found work accompanying dance classes (which she preferred to accompanying singers), and by the early 1930s she was well known locally as an accompanist for dance recitals. Los Angeles was a spawning ground for modern dance; Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn had begun their company there in 1913, presently giving Martha Graham and Doris Humphrey their early opportunities. These dancers had left by the time Arvey became active in the field, but there was still wide interest and a lot of activity in modern dance. (In Los Angeles, modern dance was said to have a quality of naïvaté that distinguished it from its New York counterpart.)[14] She reported extensively for the American Dancer, founded locally by Ruth Howard in 1927, especially after Howard moved it to New York in 1932.[15]

Arvey developed strong practical ideas about how to accompany the

dance: "In playing dance accompaniments, one follows the dancer, not the music . It is a new musical language. The accompanist must forget all he has learned about music and learn anew."[16] At the end of her book, Choreographic Music: Music for the Dance (1941), she wrote:

A good accompanist for the dance will play the music just a little differently. . . . That is, there is a lift: a rise and fall in each phrase that is almost indescribable. At least, it is not possible of description with ordinary crescendo and diminuendo marks. A curve of the hand or a rising gesture will occasion this "lift." It follows that a successful composer for the dance will have in his music that indescribable something that gives to choreographic music, on the whole, that strange, unrigid, rhythmic, living character![17]

As for her music, especially her interest in the piano, Arvey told an interviewer, "My family was a music-loving family, although they were not performers in any way. I don't know where I got that from."[18] At Manual Arts, she took courses in harmony, music history, and composition, at a time when such courses were widely available in Los Angeles high schools. She gave up her own interest in composition only after Still's arrival in 1934. Over the years, she worked with five different piano teachers, none of them especially prominent. She left the last one, Ann J. Eachus, a student of the locally illustrious Thilo Becker, some time after giving a recital in Eachus's studio in 1932.[19]

What was she like as a pianist? Her one surviving recording, of Still's Seven Traceries, made for Co-Art Turntable in 1940 or 1941, is of rather poor quality. The written evidence, like the recording, is equivocal. There were positive reviews, mainly in connection with her work with dancers. For example: "A masterly accompaniment for the exacting program was supplied by Miss Verna Arvey at the piano. Her dynamic power and musical understanding not only afforded a flawless support for the dancer, but in five solos of diverse moods [she] proclaimed herself a young virtuoso of great promise."[20] A 1933 radio performance by the Raymond Paige orchestra on the program "California Melodies," in which she was the soloist, was noted by the New York Daily News: "[Paige's] orchestra gave a brilliant performance of Gershwin's 'Concerto in F.' A Pacific Coast crew that should visit the East."[21] Still heard the broadcast and reacted with surprising warmth:

I must pause in the midst of the mad rush to tell you of my reaction. . . . I was more than repaid for my eagerness. You are an artist; a soul through whom higher beings speak to mortals. Under your fingers the piano sang, then spoke

in caressing tones tinged with sorrow, and then spoke in more authoritative tones. . . . I hope I may hear you again, many times.[22]

In her own estimate of her skill, Arvey was not so flattering. She wrote that she was chosen to play a piano solo at her high school commencement "despite the fact that I actually was not the best concert pianist then in school."[23] For three consecutive years (1930–1932) she auditioned unsuccessfully for the position of pianist with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. "Musicians always thought I was a good writer; writers always thought I was an excellent pianist," she wrote in a "Scribbling." Eventually she took an empirical approach to exploiting her talents:

Countless times I decided I'd never try for anything again. Each time I changed my mind. For, on the instant, it seemed as if there was always an open life beyond, instead of a door closing off the life behind. . . .

There came a time when I resented being dubbed a dance accompanist forever, and wanted to strike out for myself in other lines, but luckily decided to capitalize on what knowledge I had and gave recitals of dance music and wrote books on the subject. ("Scribblings")

One of the few surviving letters from Forsythe gives another view of her thinking in early 1934:

Would like to hear a more detailed idea of what you will put into the projected "Without Bitterness." . . . I remember the poem you will base it on. It sounds like a good idea: but can it be done Without Bitterness? That's the problem! . . . I will wait impatiently for it, for it will be emmensely [sic ] interesting to see how you have reacted to this America . . . can't remember ever reading anything of the sort. . . . Africs are almost moaning in print on the subject, but the story of the young Jewish intellectual must be told in your book. . . . Do it well, and don't spare America![24]

While still at Manual Arts High School, Arvey demonstrated an interest in "the new" as it was developing in Los Angeles, shown both by the connection she cultivated with Cowell and by her work in behalf of modern dance. By the early 1930s, her "modernist" acquaintances in L.A. included John Cage and Harry Hay. Arvey was sufficiently interested in Cage's ideas that she arranged for him to perform at the Mary Carr Moore Manuscript Club.[25] Forsythe was on the periphery of this circle, mainly through Hay. Whether Arvey had met Wallace Thurman or Arna Bontemps in her early high school days is unknown, but her "Scribblings" include a description of an inebriated Thurman at a party given by Still in his honor in 1930 and attended by Forsythe. Arvey's acquaintance with musical modernists expanded in the early thirties; in

late 1933 and early 1934, she spent some weeks in Mexico, interviewing composers and listening to as much music as she could. With help from Carlos Chávez, she gave a concert in Mexico City in January 1934.[26] An unpublished novel, "Beware of Bandits, Señorita," also resulted from this trip.

After several seasons of increasing prominence, Arvey attempted her most ambitious public performances, beginning with a concert in Los Angeles on November 3, 1934, and continuing with a tour that took her to New York City, Cuba, and Colombia. The Los Angeles performance was sponsored by Norma Gould's Dance Theater Group, for which Arvey frequently played, and was given at Gould's dance school. It was labeled "A program of Idealized Dance Music" and included music by Galuppi, Bach, José Rolón, Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Neupert, Chopin, Ravel, Friedman-Gaertner, Arvey, Smetana, Still, Milhaud, and Handy.[27] A publicity item and a review give a picture of her.

Small, dark-eyed, nervous—they call Verna Arvey a revolutionary pianist. The night of Nov. 4 she will show Los Angeles a new approach to music, . . . piano idealizations of dance compositions.

"To go beyond the notes, clear through technique, to the spirit, to summon dancing images in the mind of each individual in an audience more true to the music than any interpretation by a flesh-and-blood dancer, that is my desire," she says.[28]

Rob Wagner's Script, a local weekly, carried a review that gives a visual description of her playing:

When she gets to the piano she starts in with the serious business of playing and saves her calisthenics for the privacy of her bedroom, a very agreeable change! Her work with dancers has given Miss Arvey a sense of dramatic values not possessed by most pianists. At a concert, one not only hears, but sees as well, and her use of lights was sufficient to hold audience interest so that nothing marred the enjoyment of a nicely balanced program.[29]

About the colored lights, a realization of the color-sound associations that were a feature of early modernism, Arvey commented in a "Scribbling": "My use of colored lights—perhaps superficial, when considered in the light of all those detailed treatises on color and sound combinations, but really more fundamental than all of them."

A few weeks later, she performed at a symposium sponsored by Henry Cowell at the New School in New York. No program survives, and there is no indication in Arvey's diary as to what she played. There

is very little evidence about her reception at that concert. Two months after the performance, Cowell wrote that she had "made good" at the New School.[30] But no review has been located in any of the papers or journals listed by Cowell as having sent critics.[31] A letter from Hedi [Korngold] Katz, the founder of the Music School of the Henry Street Settlement, becomes the most revealing report.[32] It addresses Arvey as an artistic personality with teaching potential rather than as a pianist:

My dear Miss Arvey: I have heard you last Friday at Henry Cowell's forum at the New School. . . . What I would like to know is, do you plan to return to New York, and, if so, would you be interested in teaching at our school? Also, what subjects would you care to teach? I would like very much to have you connected with the Music School, after the impression I got that evening. Would you kindly let me know? Sincerely yours, . . .[33]

No further comment about this trip has been found.

Influenced by the overall success of Cowell's New School symposia, Arvey determined to attempt something similar in Los Angeles. Her symposium differed from Cowell's model in several ways. It was held in a dance studio, reflecting not only what was readily available to Arvey but also her sense of what was appropriate. She invited both established and new composers, with the idea of seeking common ground between old and new. The established composers included Mary Carr Moore and Charles E. Pemberton. The "new" ones, including those new to Los Angeles, were Joseph Achron, Hugo Davise, Gilberto Isais, Richard Drake Saunders, Arnold Schoenberg, William Grant Still, and George Tremblay. Artie Mason Carter, the founder of the Hollywood Bowl (long departed from the Bowl's administration by 1935), remained an enthusiast of the "new," and was invited to moderate the discussion that was to follow. The event presented a Los Angeles-specific window on the "new," with its mix of local composers and teachers, film composers and émigrés. Several letters report the proceedings; they suggest that the event failed to create rapport among the factions and that "common ground" remained, to say the least, unlocated. Artie Mason Carter's sets the tone:

Dear Verna: I can't bear your great disappointment after all your sincere effort, altho I feel you are wrong to feel the evening was a failure. To me it was

truly interesting and I don't want you to promise never to attempt it again! We must have leaders for the cause of contemporary music and you are an excellent one. . . .

You played beautifully—gave a fine impression of a charming work—that and the Schoenberg songs (The Book of the Hanging Gardens ) were worth coming a long distance to hear. . . .

Don't be discouraged. You are too young and too valuable. Bless you my dear! Faithfully, A.M.C.[34]

A fuller (and less positive) account comes from the shaky hand of another of the old guard. Charles E. Pemberton, once Forsythe's composition teacher, had been a Los Angeles resident for at least thirty-five years and was still active as a teacher at the University of Southern California in 1935.

My dear Miss Arvey:

. . . it was kind of you to think it necessary to apologize for the affair not turning out as you had planned. It was not your fault and you did everything you could to make it a success. . . .

I suffered horribly during those 15 Schoenberg songs. (Was it 15? they seemed endless.) I lost count, breaking out in a cold sweat. It was poor taste upon the part of this Rogers lady to sing all those songs upon a program of such a character. . . .

[When] I peeped behind the scenes, . . . I thought I heard this charming Arvey lady say, "My God what have I got into." . . .

It was of course to be regretted that the lateness of the hour the program closed left no time for discussion. But again, that was no fault of yours.

I expect you are going to think me "horrible" for writing so frankly, but it's just between us, and somehow it relieves my mind, like escaping steam from an engine relieving the pressure on the boiler.[35]

Arvey reported further complications. The genial Cowell failed to appear at the last moment, although they delayed the start for him. The less genial Schoenberg did not receive his invitation in timely fashion, even though his songs were scheduled and he had coached the singer in advance. Calista Rogers, his singer, stretched out her part by reading English translations before each song, helpful in the absence of program notes but serving to prolong the agony of Professor Pemberton (and perhaps others).[36]

Arvey did not repeat this experiment; in fact its failure seems to have encouraged her to withdraw from the battlefield between modernists and traditionalists entirely. Increasingly, she immersed herself in her work

on Still's behalf, although she continued to play for dancers and write about the dance. How fully she withdrew will become clearer presently.

Forsythe made a deep and lasting impression on the young Arvey, and she on him. His present for her high school graduation, manuscript copies of several of his own songs, is by far the most personal among the handful of modest presents she listed in her graduation program.[37] He could hardly have resisted telling Arvey about Still well before he introduced them, given the unbridled enthusiasm and openness of his few surviving letters.[38] She may well have read his "William Grant Still: A Study in Contradictions" at the time it was written, or even helped him edit it, soon after Still returned to New York in the summer of 1930.[39] Thus she was aware quite early of the contrast between Forsythe's zealous theorizing on racial matters and Still's methodical focus on practical applications in music.[40] Her relationship with him was already strained before Still's arrival in 1934:

My dear friend Verna:

As I write to you now, all the years during which I loved you as a dear and cherished friend stand congealed on the pin-point of the moment.

Just how anything entered into our lives that could change this feeling a bit is extremely difficult to say, but ever since a few months ago I have felt that I was losing Verna . . . the Verna that had meant so much to me . . . the Verna who meant beauty . . . not so much piano playing, but the loveliness of music written for the piano. I don't think that I thought of Schumann's beautiful Fantasie, or Rachmaninov's 2nd Concerto, or Beethoven's Hammerclavier Sonata, or Mozart's C minor . . . without thinking of the Verna . . . MY Verna, as the executent [sic ], and the catalyst.[41]

The melodramatic "farewell" with which this letter ends is defused by a postscript: "Next morning: Dear Verna: All is true, save the goodbye. Don't say goodbye, Verna! Hello is so much nicer a word!!!!!!!" An undated letter from Arvey to Forsythe, now known only in Arvey's transcription, may well have been in response to this letter:

It just occurred to me that you have a very wrong idea of me. I'm not deep or profound or intellectual. I may be intelligent, but not intellectual. And I don't like to read philosophic things. I want things with a human side. And I don't like to study technicalities and big words. And I don't like to write un-understandable stuff just because it is arty. And I don't want to be a famous artist, I want to do my work and do it well. . . . [And] anyway, the

adjectives you use in describing me aren't true. I'm just myself, that's all. Don't idealize me.[42]

Even if the two letters are not directly connected, they reveal the developing conflict between Arvey and Forsythe that was exacerbated by Still's arrival.

The transition from the rather enterprising, adventuresome early Arvey and the Arvey of In One Lifetime is both remarkable and sad. At one point, probably later on, she commented on her decision to remain in southern California and not seek further education in this way:

I was born in a section of the country which has spawned some important creative minds, as well as some outstanding ideas. It has also routinely absorbed many of the "greats" from other parts of the nation and of the world at large. So many came to live and work in the friendly climate of Southern California that it was always a surprise to find that many Easterners still considered us "provincial" and still thought that we on the West Coast were in dire need of their superior "leadership"! . . .

At any rate, right at hand were so many big "names" in so many professions, so many interesting artistic projects and so much to absorb that I soon decided to cast down my bucket where I found myself. It came up loaded with nuggets of knowledge."[43]

Likewise, she recognized the loss of further systematic study indirectly in one of her "Scribblings": "The transition from a bright youngster with exceptional promise to an artist in competition with all the mature minds of the artistic was terribly hard."

It seems that Arvey's public means of maintaining her equilibrium during those "exasperating years" was humor. One of the dancers she accompanied wrote about her:

She whose humor unfailing

Strips our leaden-weighted woes

Of their well-forged armor

And with ruthless, Puckish foot

Kicks over the cup of dignified Care

And holds the mirror of Ridicule

Before wry-faced misfortune. . .[44]

These comments add poignancy to a recollection from a member of Arvey's circle in the early 1930s. Fifteen years later, following World War II, its writer returned to Los Angeles, where he renewed his friendship with some dancers from the old Norma Gould studio, where Arvey

had often played and where she had presented her New Music Symposium in 1935. He writes,

I asked [people] like Waldeen Falkenstein or Teru [Izumida; both dancers for whom Arvey had once played] about Verna, and was told "Oh, she's absolutely changed since her marriage: all that laughter and sparkle has totally disappeared. D'ya remember how—at times—she could be almost winsome? That's all gone." Lester [Horton] even said "if you can believe it, she's even pushy and sort of tiresome now."[45]

How does one account for this transformation? Several events must be considered, though none really explains it. The resolution of the triangle with Forsythe and Still may have been traumatic for Arvey, as it was clearly devastating for Forsythe. She had resisted Forsythe's formulation of a triangle to begin with, writing to him, "There is one Billy and one Harold. They each have their particular niche. I have never been able to confine myself to one particular friend. . . . That should not alter a friendship as old as ours has been. Why can't we all three be together, instead of two . . . or two? I am always your friend whether you like it or not." She also may have precipitated the crisis through what seems her heartfelt advocacy of Forsythe's writing. She had introduced herself by mail to Carl Van Vechten, a major patron of the Harlem Renaissance, and represented Forsythe to him with an eloquence notably missing from much of her writing about Still. The letters from Forsythe to Van Vechten, first informative and assertive, then crushed, along with Arvey's rather stiff reply to Van Vechten's obviously worried query ("I think you have done Harold a far greater service by doing exactly what you did. . . . [A] little personal triumph is relatively unimportant when it comes to making finer human beings of people!"),[46] are quoted in the chapter on Forsythe above. The undated "Scribbling" that identifies him as a "drunkard" who "lied" about her probably dates from 1935, at about the same time. She had known of Forsythe's deafness earlier, though she seemed unaware of its progressive nature, and she believed he had tuberculosis. What looks like his accelerating physical deterioration at this time, combined with her helplessness and perhaps even guilt about it, must have been painful.

Both Arvey and Forsythe had worked with Still; now Forsythe's working relationship with Still was broken off and Arvey's began to replace it. Presently Forsythe's poem for the score of Dismal Swamp, just in preparation in 1935 for the New Music Edition, was removed in favor of another, inferior one by Arvey. (See the appendix to this chapter for

both texts.) The ballet Central Avenue, for which Forsythe had provided the scenario, was eventually listed as withdrawn, replaced by the similar Lenox Avenue, to a scenario by Arvey. (Here the reasons for the switch are not so clear.)[47] Of the music from this relatively short period, only the score to Blue Steel continued to circulate to conductors. Arvey continued to write about it enthusiastically in her 1938 monograph. It was withdrawn only when Troubled Island was completed several years later, probably to give the new score a clearer field.

Having drawn closer to Still, Arvey now had to face public opprobrium over the interracial relationship. Still's 1938 suit for divorce was front-page news in the Negro press. The harassment Arvey sustained from a handful of African American women when her relationship with Still became known was intimidating and unexpected:

Dear Langston,

. . . We have had a barrage of the dirtiest, lousiest, most malicious anonymous letters you can imagine. They even sent them to newspapers, in an effort to turn people against Billy on my account.[48]

In response, the couple kept their address as secret as they could and maintained an unlisted telephone number; Arvey even hired a private detective on one occasion.

The change in their lifestyle after their marriage may have been much more difficult for Arvey than is suggested by a fragmentary "autobiography" of Still, which she undertook to write in his voice rather than her own: "We began to live a quiet life. Now that I had a real home I wanted to stay in it and enjoy it as much as possible. . . . Our staid life would scarcely appeal to lovers of thrills, but for us it is the only real romance."[49] If Still worked ceaselessly at composition, Arvey, too, applied herself diligently. She continued to write on dance, in addition to undertaking many articles on Still and helping him with his correspondence. In preparation for writing, she amassed numerous scrapbooks on race, anticommunism, and other topics.[50] She copied out extended passages from books on topics of interest, such as on Dvorak's[*] sojourn in America.

In fact, Arvey seems to have tried hard to surrender her identity to Still's, willingly adjusting her views to his, being consumed by the slights he and his work experienced, and accepting the subordinate role that Still's working method required of his librettists. She may well have been disappointed that their marriage and their working relationship did not bring about the major change in race relations that she desired and Still

accepted as a basic purpose in his life. Her account of the 1935 symposium's outcome in the Still "autobiography" quoted above eerily projects how fully she would eventually abandon her own persona: "My wife says that if any more composers' symposiums are given, someone else will have to give them. She spent the following day in bed."[51] Forsythe's question—"can you do it Without Bitterness?"—was very much to the point. Arvey's disappointment at not getting to study at USC left a residuum of anger; indeed, her bitterness at the ability of some of their friends to travel to New York for the 1949 production of Troubled Island when she could not is apparent in her letters to Still before the production.

Whatever the reasons, the result was that Arvey and Still reinforced each other's developing anxieties, helping each other as they lost their individual perspectives sufficiently to blame their troubles increasingly on a grand communist plot (discussed in '"Harlem Renaissance Man' Revisited" below). This began to be evident in the years immediately following World War II. After 1949, the process was carried to an extreme. It would seem that Arvey had conscientiously reflected Still's ideas and his language in writing for and about him in the early years of their relationship. Her conscientiousness continued, but the language became more and more her own. In the process, it became more forced and convoluted. The conclusion of her very late (1969, post-Black Arts movement) discussion of the "I Got Rhythm" controversy is carefully coded to invoke distinctions about class and class-based genre, chosen with a certain implicit snobbery:

As composers, the difference between Gershwin and Still is obvious. Gershwin approached Negro music as an outsider, and his own concepts helped to make it a Gershwin-Negro fusion, lusty and stereotyped racially, more popular in flavor. Still's approach to Negro music was from within, refining and developing it with the craftsmanship and inspiration of a trained composer.[52]

Her avoidance of opposites for "Gershwin-Negro fusion," "lusty," and "stereotyped racially" that might apply to Still is surprising, given the opening of the paragraph. She introduces the racial issue with these phrases and then fails to follow through on the terms she herself proposes. The suggestion instead that something "popular in flavor" does not admit of "craftsmanship and inspiration" or cannot come from a "trained composer" goes against the grain for many readers and writers who cherish (as an ideal, anyway) a more egalitarian approach to aesthetic evaluations; in fact, it rejects the craftsmanship Still brought to his

commercial work. The use of "from within" in opposition to "outsider" is an attempt to evade a simple inside-outside contrast in favor of the suggestion of something more uplifting on Still's part. The result is an argument that, through its failure to follow through, does Still no good. The paragraph adds up to a late and not well thought out attempt to defend Still. In any case, Still allowed Arvey to take the lead only in one matter, the family's political posturing about anticommunism. It was no easy thing to stay balanced on their own personal troubled island under the pressures she attempted to carry for them both.

The issue of the quality of the librettos she provided for Still should also be addressed, however briefly. The later ones are indeed disappointingly similar, tending to dwell on the common themes of loyalty and retribution despite their varying locales. Costaso, Still's fifth opera (composed 1949–early 1950), engages with themes of loyalty and friendship, major issues in the Stills' lives as they worked on it. Arvey's text repeatedly extols these values, along with domestic serenity over an extended period. For example, Carmela, in her first-act aria about Costaso, does not sing of her passion for him; instead, she sings of their common peacefulness and serenity, for which they have abandoned passion and high ambition, perhaps as Still had done by going to Los Angeles:

Far off riches beckon, false in their promised yield, / while here fortune lingers steadfast and secure. . . . / When life moves on serenely, when friendship's glow surrounds us, time itself becomes timeless. / The moments pile on moments, the hours grow into days, lengthen into years, to eternity. . . . / Our golden moments bring us joy forever!

When given the order to leave home and search for the city of gold, Costaso sings:

Love bids me stay at home / where peace and devotion occupy our thoughts, / where comfort is our watchword.

In the desert, as they despair of rescue, Costaso's friend Manuel voices the value of friendship and loyalty in the opera's most forthright declaration of love:

Your friendship more than repays me. / On the highway, in the town, / people pass and glance in friendly fashion. . . . / Where devotion? Where everlasting love? . . . / When at least the spark is found, when among strangers a friend appears, / then I return his love full measure. . . . / One friend, and I search no more.

Plotting by individuals is the order of the day.[53] We see Armona plot almost from the beginning to send Costaso to his death in order to win Carmela to himself. We see Carmela confront Armona in Act II Scene 1 with unheroine-like strength and tenacity in her husband's behalf. Her counterplot emerges only in the final scene, a moment or two before Armona is undone by an emissary from the distant capital. The last-minute developments that bring about Armona's fall and Carmela's triumph may be autobiographical for both Still, who had come to believe that his triumphant production of Troubled Island had been made to vanish with comparable unexpected suddenness, and Arvey, whose heroine managed at the last moment to subvert the passive-love object role expected of her as a matter of operatic tradition.

Thus Arvey's libretto and the jointly devised plot of Costaso reflect a view of the world in which heroes are isolated and manipulated by the plotting of either "bad guys" in positions of authority or "good guys" in the form of wives and other loyal but subordinate friends dedicated to the proposition that "Costaso always wins." Arvey's language is often neither graceful nor telling.

Yet Arvey's presence and willingness to collaborate cannot be dismissed as purely negative. She proved a reliable supplier of texts, and Still was a full participant in the devising of the plots he set. In New York, Still had found it difficult to find librettos and librettists with whom he could work. Still's choice of librettists was typically governed by their accessibility as much as or more than by their literary distinction. Grace Bundy, his first wife, had supplied song lyrics as early as 1916; later she wrote letters in his behalf, just as Arvey did later on. In the late 1920s Still began work on an opera ("Rashana") that was based on the plot of an unpublished novel by Bundy. It was to be versified by Countee Cullen, but Cullen was distracted by his personal life and never pursued the project. In Los Angeles, Forsythe was at hand (displacing Bundy, as Arvey was to displace him) to work on Blue Steel . When Langston Hughes agreed to provide the libretto to Troubled Island, Still wrote to him, "Please remember that it is absolutely necessary for us to keep in touch if we are to collaborate."[54] Arvey's collaboration on librettos did not begin until Still himself grew impatient with Hughes's inattention. As late as 1939, he asked Arna Bontemps for a libretto; he collaborated soon afterward with Katherine Garrison Chapin on And They Lynched Him on a Tree .[55] The possibility that Arvey's convenient accessibility as a librettist discouraged him from seeking out and setting

a richer variety of opera texts must be balanced against his early difficulty in finding satisfactory texts to set at all.

There is evidence, published and unpublished, about how the Stills' collaborations worked. For example, Still wrote to the New York Times critic Howard Taubman some months after the New York production of Troubled Island concerning the new opera (Costaso ) he was working on in collaboration with Arvey.

The libretto is by my wife—Verna Arvey, and we are working in a way which seems to us satisfactory, though not usual. The plot we developed together, then she wrote out the libretto, each recitative indicated exactly, but each aria indicated only by the opening lines. I then set the opening lines of the arias and went on from there, developing each aria musically. Afterward, she put the remaining words to the music. This method has given me more leeway than I would have if I had a set libretto from which no deviation is possible. At present I am completing Act II of the opera as far as the music is concerned, but the entire libretto is finished.[56]

Like most of Still's letters after their marriage, this one was typed on Arvey's typewriter, most likely by her, and signed by Still. The question arises, who wrote it? In my opinion, after receiving the inquiry from Taubman, they discussed what topics to address, Arvey wrote out a draft reply, and Still signed it, with or without changes. This letter survives in a carbon of its finished form, so any changes made on the original in longhand are not present. Since it was clearly intended for publication, Arvey was performing a useful public relations function, giving Still this opportunity for publicity while sparing him the necessity of writing it himself.

There is draft evidence about one earlier collaboration, containing material that involved the film industry and other composers, from several years earlier. Still responded in 1940 to a symposium-by-mailed-questionnaire on film music; his answers are quoted at length in "Finding His Voice," above. A draft of his replies shows that Arvey typed out the questions, leaving space for his answers. She appears to have written down his comments as he spoke them, preserving language that is reminiscent of Still's writing style from his earlier, New York period.[57]

The anticommunist writings present a more difficult problem, since the Stills' shared position on this topic played a part in their later isolation. Authorship of the 1951 speech read by Still in which he named a rather long list of persons he believed, without real evidence, to be communists (quoted in '"Harlem Renaissance Man' Revisited," below) was claimed by Arvey in her correspondence with the editor of the American

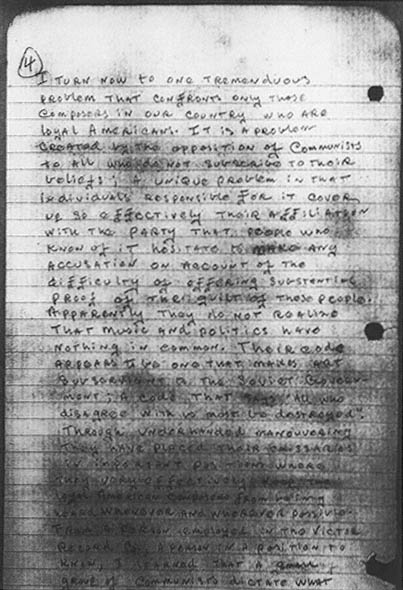

Mercury . One begins by assuming that she is the author of other anti-communist talks given by Still, but that is not the case. In May 1949, Still spoke at Mount St. Mary's College in Los Angeles on the general topic of problems faced by the composer of "serious" music. He divided the problems into external ones, such as taking the critics seriously, and internal ones, such as deciding on a style and finding inspiration. He drafted the speech himself (see fig. 11), then reordered the paragraphs for Arvey to type. His paragraph on the communist threat is quoted in full here. Where Arvey made changes in her typescript, Still's words are bracketed. Her substitutions appear in boldface.

I turn now to one tremendous problem that confronts only those composers in our country who are loyal Americans. It is a problem created by the opposition of Communists to all who do not subscribe to their beliefs; a unique problem in that individuals responsible for it cover up so effectively their affiliation with the [party] Soviet controlled group that people who know of it hesitate to make any accusation on account of the difficulty of offering substantial proof of the guilt of these people. Apparently [they] these Reds do not realize that music and politics have nothing in common. Their code appears to be one that makes art subservient to the Soviet government; a code that says, "All who disagree with us must be destroyed." Through underhanded manoeuvering they have placed their emissaries in [important] key positions where they very effectively [keep the] prevent loyal American composers from being heard whenever and wherever possible. From a person [employed in the Victor Record Co.,] in the employ of one of our most prominent recording companies; a person in a position to know what goes on, I learned that a small group of Communists dictate what music shall and shall not be recorded by that company . [crossed out material] I shudder to think of what could happen if these people had greater power. One thing is certain[.]; Greater power they will surely have unless something is done to curb them. Incidentally, I suggest, if you have not already seen it, that you look over the group of Communists whose photos appear in the April 4th issue of LIFE. In it you will find listed three men very prominent in American music.—I'm quite [underline removed ] certain Life made no mistake in these three instances.

Her editing is light, occasionally intensifying Still's language, and in one case, the reference to the Victor Record Co., serving to weaken it.

How, then, did Arvey influence Still's career? She brought common interests, useful skills, and total dedication; most of her actions in his behalf were based on her best judgment about his interests and in fact often amounted to simply carrying out his wishes. Several factors need to be considered in reevaluating her judgment now. The role of race clearly

Figure 11.

Page from draft of Still's speech for Mount St. Mary's College, 1949.

Courtesy of William Grant Still Music.

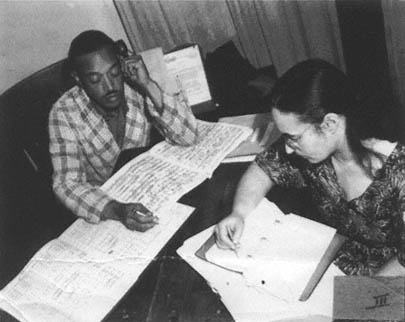

Figure 12.

Still and Arvey at work.

Courtesy of William Grant Still Music.

affects our perception of her position. From the days of Still's earliest successes as Varèse's protégé in New York's modernist circles, it seems that virtually everyone who knew him or knew of him or his work had an agenda for him that turned on racial difference. So did Still himself; so did the critics (see the introduction and "'Harlem Renaissance Man' Revisited"); so did both Forsythe and Arvey; and so do we. It is easy but not very enlightening to blame her for those decisions by Still that seem to go against the grain in one way or another. Most of these were set forth by Still in typescripts that preceded his arrival in Los Angeles. Class distinctions of various kinds are also an underlying issue. The concert music and operas Still composed, although intended to have broad listener appeal, were intended for performing organizations and venues (mainly symphony orchestras and opera houses) that drew middle-class, largely white audiences. Moreover, the quiet lifestyle chosen by Still and protected by Arvey served to reinforce the "peculiar isolation from [his] race" that Forsythe had noted in 1930, years before Arvey and Still married.

Gender issues likewise play a role in our evaluation of this complex relationship. The formulation of aesthetic distinctions by the modernists that served eventually to marginalize Still's work bears an uncanny resemblance to the process by which women, too, were marginalized; misogyny was a significant aspect of the aesthetic approach of the male American modernists of the 1920s.[58] If Arvey can be blamed for Still's aesthetic decisions, then the modernists' hostility toward Still can be explained away on quasi-"objective" grounds unrelated, on the surface, to these tricky issues of race and class. From another direction, theorists of black culture, specifically including writers on the blues, have tended to formulate their ideas in masculinist terms, making it easy to avoid the gender-related questions that are important to understanding Arvey's role in Still's life and career.[59] Both of these approaches may help explain Arvey's position as a lightning rod for attacks really aimed at Still, attacks that obscure both Still's thought and Arvey's. That these have not yet been addressed is illustrated by the treatment of her In One Lifetime by its editors as a book on Still rather than one on Still and Arvey, resulting in both the deletion of material that describes her development and the mishandling of other materials. The recent bio-bibliography of Still includes a listing of "Writings by William Grant Still and Verna Arvey." Only thirty-four of the 168 articles she published after leaving school are included; while many of these do not relate to Still, there is no indication in the headnote that the list is a selective one.[60]

One might think fruitfully about Arvey in terms suggested by Bonnie G. Smith's article, "Historiography, Objectivity, and the Case of the Abusive Widow," in which a "consistent pattern of diatribes" is shown, aimed at a series of widows of literary figures who either "managed a dead husband's reputation, edited his work, or claimed an independent intellectual status for herself." Smith discusses in detail numerous attacks by scholars on the reputation of Athénais Mialeret-Michelet, the widow of the French historian Jules Michelet. She concludes that while Mialeret-Michelet was inferior to her spouse as an author and scholar, the attacks on her have been so extreme as to suggest some other underlying issue, one she finds to be misogyny. "Wrapped in the mantle of science and impartiality, the saga of Michelet mutilated by his widow and rescued by heroic researchers is a melodrama whose psychological dimensions we should begin attending to, if only to understand the world of history better."[61] In Arvey's case, it would seem desirable to avoid complicity in the male modernist composers' virtually automatic anti-

woman rhetoric, a reaction against the prevailing characterization of music as an effeminate occupation in the world of middle-class whites.[62] Arvey, after all, had established a local reputation as a performer, writer, and advocate of contemporary music; she had been invited to teach in New York City as a result of her presentations of unfamiliar music. These things she either gave up or placed at Still's disposal.

If many of the things for which Arvey is held accountable really reflect Still's choices that may have been contradictory to the expectations of his friends and supporters, then she has been unfairly blamed for carrying out his wishes. Arvey often stated that she regarded their professional relationship as a partnership, a position that may have helped her become a target. It is clear from the record that Still, a major creative force, was in fact dominant. If for no other reason than her constant presence from 1934 on, it is important to consider what she brought to the relationship, and how the relationship changed them both.

As in the case of the "abusive widow," Arvey was indeed a talent far inferior to Still. If she became, especially after 1949, his political voice, she also represented his artistic and political wishes faithfully in the years that preceded the production of Troubled Island, that is, from 1934. Her activity as a gatekeeper for him, protecting his composition time, was something he clearly welcomed. But the isolation that eventually resulted may have created a more destructive situation than necessary, seen best in their mutual difficulty with the Black Arts movement and other political developments of the 1960s. Even before that, Arvey was the writer of his intemperate and uncharacteristic anticommunist speech and must bear that responsibility, while Still was responsible for delegating his political agency to her and for reading her words in public. Yet Still's aesthetic judgments about his music were always his own, including those on which the latter part of his career is based. I am convinced that Still's concern over the representation of Africa and African Americans in his music, and therefore his decisions about what to compose and how, antedated his relationship with Arvey, and that he explicitly retained aesthetic control over his artistic decisions. Recognizing that his artistic judgment was set, it was Arvey who accepted it as absolute and gave up her own personality in service to Still and to his work. Very likely she was the one who attempted to take on the burden of racial resentment, thus freeing Still to continue creating but assuming for herself an unbearable emotional burden. The relentless poverty that was their lot after World War II must have contributed to her alienation as

well. This, along with her unconscious resentment at having submerged her identity so fully in his, could well explain the anger of her later writing. If Still's position as an African American brought him unusual challenges and set him a path demanding extraordinary resourcefulness, and if he chose solutions that raise their own questions, we are better served by addressing these issues directly rather than by blaming Arvey.

To conclude, it is clear that Arvey began with an artistic persona of her own, however fragile it turned out to be. Early on, one can see emerging a mix of talent, energy, chutzpah, and self-doubt. Her broad interests represented something of a Los Angeles version of the "new," less fiercely grounded in rebellion against the nineteenth-century musical canon than we have come to expect elsewhere, more receptive to the work of "others," including Still, Forsythe, and herself. Later on there appears the weakness that resulted from submerging herself in the work first of Forsythe, then of Still; the suspicion that developed from her own distance and the exclusion and subordination of her own creative energy; the defensiveness that grew from the ugly incidents that went along with her racially mixed marriage; the narrowness of view that allowed her to perceive the indifference or opposition that was Still's lot as a pioneer as a communist plot. To return to the initial query about what Arvey brought to her relationship with Still, it would seem that her early eclecticism was more compatible with Still's ideas and his music than was the "new" in New York. She brought competence in handling his affairs, sympathy with his political views, an interest in dance and theater, energy and enthusiasm and willingness to subordinate herself to his needs. If anything, she served him too well. Whether she deflected Still from his purpose or facilitated his chosen path seems to be a judgment that depends on the observer's interpretation and perhaps on what part of Still's career is being considered, at least for now.

Appendix

DISMAL SWAMP [ 63]

[Forsythe's text, suppressed]

My heart pierces the thick pulpy wall of your body

To be caught in the delicately spun web of your spirit,

And drawn deeply into a core beyond the world, where

Resonantly a strong voice sounds for me your final Truth.

[Arvey's alternate text, as published:]

Oh, swamp! your gloomy surface strikes me cold

Your sombre stumps no joy awake

Yet beyond your rotting, odorous mould

Strange charm greets those who penetrate.

No longer dismal, swamp!

Wild ferns, green moss, small twigs a-spin

Your beauty acrid; verdure damp

What joy for those who gaze within![64]

THE BLACK MAN DANCES

[Forsythe's texts for each of the four movements; this entire piece was not published or performed.]

In the night the young man's flute is a shadow

Trailing from the spirit of his lost love.

Deep in the jungle; gloomed darkly in his song,

Slowly dances the heart of the lonely lover.

Sharp red lights crackle in the [jungle],

Dancing to the pounding of feet.

The poignant slowness of a hidden sorrow

Slows, once, the clear brightness of rhythm.

Their feet are leaves from an autumn tree,

They float, O Jazz River, on your bosom,

The piano swells thru smoke and gin,

The cabaret walls stand like a levee.

"Strut it, sistuhs an' brothuhs, Rent man on de way!"

Shout it voices, shoulders, hips . . .

Blacks and browns, clap hands and shout:

"Shout it sistuhs an' brothuhs, Rent man on de way!"