IV

Bergère ô tour Eiffel le troupeau des ponts bêle ce matin

Apollinaire, "Zone"

Shepherdess oh Eiffel Tower the flock of bridges is bleating this morning

If the representative figure of this new Paris and the new age foretold is the intellectual, assuredly the exemplary monument is the Eiffel Tower. As the fall of the Vendôme Column sealed the end of romantic Paris, so the Eiffel Tower proclaimed the modern Paris that faced the twentieth century. So familiar has the tower become, so inconceivable is Paris without it, that we forget not only how singular a structure it was in 1889 but also, over a hundred years later, how unique it still is. It has the simplicity of the triangle, a spire reminiscent of a cathedral, and intricate iron tracing that makes ascent an experience of a moving collage. There exists no other structure like it. Because the tower is sui generis, it is instantly recognizable as the emblem of modern Paris. Like the ideal of the intellectual in fin-desiècle France, the Eiffel Tower claims our attention without reference to its particular site, a detachment that makes the association with the city as a whole all the easier, all the more "natural." There is no necessary connection between the tower and the Champ-de-Mars. Its singular form would set the tower apart whatever the site. And, unlike the Vendôme Column, unlike monuments generally, the Eiffel Tower neither commemorates an event nor honors an individual. It appeals to no cultural memory other than those that it has itself created. Nor, whatever uses are made of it (telegraph, radio, and now television station, restaurants, historical exhibits) does it serve a purpose other than representational. Even the shops in the tower sell the tower itself, in what seems to be an infinite number of forms.[*] The Eiffel Tower

The variety of forms in which the tower is presented is truly astonishing: statuettes, paper weights, tee shirts, ashtrays, and such, but also bottles of perfume and brightly colored bath sponges shaped like the tower. And any visitor who just might possibly have forgotten to pick up an appropriate souvenir on the spot can repair the omission in the gas stations on the main autoroute leaving the city.

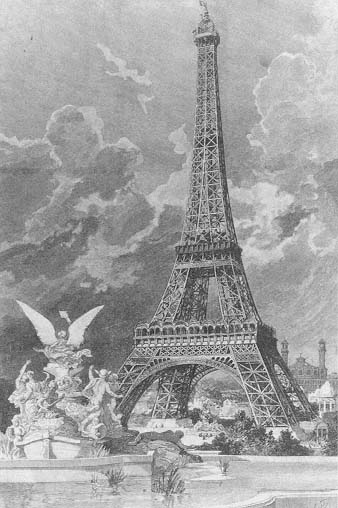

Plate 20.

The Eiffel Tower at the World's Fair of 1889. As the fall of the Vendôme

Column sealed the end of romantic Paris, so the Eiffel Tower proclaimed a new

and aggressively modern Paris. Built for the World's Fair of 1889 and for the

celebration of the centennial of the French Revolution, the Eiffel Tower resolutely

faced the twentieth century. The allegorical statues of Progress in the left

foreground, all curves, wings, and drapery, throw the stark, geometric lines of

the tower into even sharper relief. The classical allegory dwindles before the

very different grace and power of the modern representation as the clouds of

change hover on the horizon. (Photograph from the Bibliothèque Nationale,

courtesy of Giraudon / Art Resource, N.Y.)

is, as Roland Barthes observes in a marvelous essay, a "pure sign," open to interpretation by every user.[22] Viewing in this context is, of course, using.

Representing only itself, the Eiffel Tower is the indisputable synecdoche for modern Paris, ostensibly above the history that ties Paris to its past and, for that very reason, resolutely open to the future. So too Zola's Paris, with its metaphorization of the cityscape into a landscape, turns the city away from its site, its past, and its history toward a vision of future grandeur that will, by implication, eclipse the present as well as the past. Apollinaire's celebrated shepherdess tending her bleating flock of automobiles on the bridges of Paris magnifies by modernizing Zola's version of urban pastoral.

Although the Third Republic put the Vendôme Column back in place, it looked elsewhere to fix the imagination of the city and the country. The column was henceforth only one of the many monuments to dot the Parisian landscape—the landscape that the Eiffel Tower defined. The Vendôme Column, like all the other monuments and buildings that harked back to one or another ancien régime, proclaimed its connections to a past, even to several pasts. It made sense only in relation to the past, however dimly perceived or, for that matter, misperceived. To the contrary, the Eiffel Tower visibly had no ties to any past. It fit within no tradition. It was truly one of a kind. The deliberate absence of manifest historical reference opened the tower to every future, and does so still today. In a city where history so obviously marked virtually every corner, the Eiffel Tower was indeed, as it was accused of being, "foreign," indisputably not Parisian, not French. Its manifest ahistoricity challenged history itself and provoked very vocal protests like the manifest signed in 1887 by writers, artists, and other "passionate amateurs of the beauty of Paris" who spoke "in the name of French art and history" against "the useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower" then in the process of construction "right in the heart of our capital."[23] Its size alone—at 984 feet it is almost seven times the height of the Vendôme Column—meant that it could be neither ignored nor avoided.

Yet, as Haussmann's Paris had become nineteenth-century Paris, so the Eiffel Tower created its own space and its own history to become synonymous with the twentieth-century city. Now all comers could master the city from above. No longer was the bird's-eye view restricted to the powerful or the imaginative. The tower became quin-

tessentially Parisian. By the time of its fortieth anniversary, in 1929, a poll on whether or not it should be torn down found few advocates of demolition. The painter Robert Delaunay, for whom the tower was a favorite subject, even went so far as to call the tower "one of the marvels of the world."[24]

That the Eiffel Tower presents itself as resolutely modern and aggressively ahistorical does not, of course, place it outside history. The very ahistoricity of this extraordinary structure fits rather neatly within the larger political project of the Third Republic. To forge a national consensus and to stabilize the country, the republican governments after 1871 slowly but surely de-revolutionized the Revolution. It took over a decade of often bitter political debate punctuated by constitutional crises for the regime to settle into the patterns that would make it the longest French government after the Revolution (18701940, a record that will hold for many years to come).

Not the least of these battles concerned the emblems through which the republic exemplified itself to France and to the world. A symbol system had to be reconstructed. The Third Republic worked diligently to build a republic that would accommodate the past with the future, a republic whose glory would draw upon Louis XIV and Versailles as well as Napoléon and the Civil Code and even the fall of the Bastille. A series of key dates charts this delicate process of ideological negotiation as the republic went about selecting its ancestors and overhauling its symbolic arsenal: 1878, the centennial celebrations of the deaths of Rousseau and Voltaire, the twin deities converted to republican duty; 1879, the vote for "La Marseillaise" as the national anthem; 1880, declaration of 14 July as the national holiday; 1885, the gigantic state funeral of Victor Hugo, the ecumenical republican par excellence; and finally, 1889, the joint celebration of the centenary of the Revolution and the World's Fair. Inaugurated in 1889 the Eiffel Tower thus participated in both the revolutionary celebration and the celebration of scientific and technological progress. Even though the organizers of the centennial most certainly bore in mind the revolutionary festivals held there, it was with the intention of rewriting revolutionary history. The Champ-de-Mars was to be the site of a festival for a new revolution. On the erstwhile military parade ground, the revolution of science and commerce made its claims. The Eiffel Tower signaled the determination of the republic to face res-

olutely forward. It would take from the past only that which could be turned to account for the France of tomorrow.[25]

Because the violence of revolution had no place in the new France, the Paris explained by the Revolution had to be redefined, reconstructed, and reimagined. Bastille Day became the national holiday, but the animation was confined to commemorating not reenergizing the Revolution. No single image of Paris at the end of the century carries the powerful charge of revolutionary Paris. The myth had lost its force.[26] The Eiffel Tower could remain the emblematic urban icon because, figuring none of them, it could signify them all. It was in a sense the "degree zero" of the city.

<><><><><><><><><><><><>

The hold of the Revolution of 1789 on the collective imagination of France and Europe throughout the nineteenth century lay in its proleptic powers. The Bastille and the guillotine, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the execution of the king, cast a long shadow forward, inviting, even requiring that the present be understood through a certain past. The future, as well, was a function of that past, one in which order and turmoil cohered. The French Revolution of 1789 substituted prophecy for teleology, a vision that gained strength from the ensuing revolutions that occurred with distressing (or exhilarating) regularity in the decades that followed the siege of the Bastille.

Paris as Revolution has claimed that nineteenth-century re-visions of Paris, and especially the myth of Paris that structured so much writing about the city, depended upon a concerted need to create and, thereby, fix and place through the language and symbols at hand. Like any other interpretation that proposes an order, these reconfigurations of Paris arrested change, the better to determine its course. Haussmann's willful transformation of Paris illustrates to perfection how "rewriting" the cityscape redirected and then determined new imaginative practices of the city.

The texts that produced the mythic city of Paris depended on a distinct nineteenth-century sense of the whole. Paris stood for something complete and, above all, knowable. Accordingly, when writers no longer felt the desire, the will, or the imaginative capacity to grasp the city as a whole, the myth of revolutionary Paris lost both imagi-

native force and literary significance. The traditional metaphors, the conventional metonymies, and the standard synecdoches no longer conveyed the complexity of the modern city; their power to define space and to determine place diminished rapidly. By the end of the century, the holistic metaphor of revolution that had guided so much thinking about the city had run its course. It was, after all, a profoundly disquieting metaphor. It channeled change, to be sure, but it did so with the promise, or the warning, of still more change to come, more movement, more mobility, more confusion, and, of course, more bloodshed. Revolution proposed change as the norm, as the fundamental category of social existence. In the end, revolution as metaphor necessarily came into conflict with the Revolution as the primal, founding event of modern French society. This historical revolution was still a catalyst, but it came increasingly out of a fixed and determined past.

There was never a scarcity of competing definitions in the nineteenth century. The conception of revolution proved extraordinarily capacious. That one talks about an "Industrial Revolution" in spite of egregious dissimilarities from the political events of the same period points both to the versatility of revolution as an abstraction and also to the need to make sense of change in terms of a comprehensive sign or emblem. Belief in revolution meant acceptance of change as a way of life and mode of perception. It would be no wonder, then, that the fin-de-siècle, quite apart from the cultural colorations that it took on in particular settings, turned toward an interrogation of time in its own search for meaning.

The myth of Paris that unfolded over the nineteenth century developed out of this perception of temporal and spatial mobility and from a concomitant urgency to check that movement. Moreover, the historical novel at its most serious and most modern—from Scott and Balzac to Flaubert and Zola—exemplifies exactly this conflation, one in which chronology and topography combine. The two, a myth of urban history and the historical novel, join in the chronotope of revolutionary Paris, the topos that infuses urban space with recognizable movements in history. The same conjunction is fundamental to making sense of the modern city, and in particular to an informed understanding of Paris as the paradigmatic city of modernity. The chronotope proves an apposite figure to the degree that it translates into textual terms the double vision that imposes time upon place

and the corresponding triple vision that brings past, present, and future together in a meaningful whole. The passion for being modern inheres in this perception of living in a place and a time that make sense on y when interpreted as a function of change, disruption, and transformation. It is, then, not by chance that the central novels in the nineteenth-century tradition produced a powerfully urban model of history. Nor is it an accident that so much of the debate over the novel as a genre should take place among French critics and about French novels, in which that model carries such intensity.

Much is made of the disruptive force of modernity and of the instability that, at least since Baudelaire, is taken as its essential feature. Analyzing and dramatizing both the social forces that produce the condition and the condition itself preoccupied writers and intellectuals of every persuasion throughout the century—from the "mal du siècle" diagnosed by Chateaubriand to the "bovaryisme" dramatized by Flaubert to the deracinement attacked by Barrès and the anomie diagnosed by Durkheim. Each interpretation, even as it accepted the universe of perpetual motion, offered meaning and stability of a sort, however illusory stasis inevitably turned out to be.

As one would expect, the exhaustion of revolution as an organizing scheme for conceptions of the city coincided with the advent of other models of interpretation. By the end of the century, urban narratives began to work through other elective affinities as literature engaged the city on other terms. Paris splintered into many cities, and revolutionary Paris dissolved into any number of images. The literature of the twentieth century moved elsewhere, and decisively inward. Writers took their inspiration from the many new cities and their myths—the idealized urban landscape of the Impressionists, the Gay Paree of cabarets, the intellectual's city of university and academies, the Paris of art studios and galleries and cafés that drew writers and artists from all over the world, and the greatest of the literary cities of the Belle Époque, the Paris of Proust filtered through the lens of memory. The Paris of the Eiffel Tower and the World's Fair of 1889 did not celebrate revolution but rather the centennial of 1789. The republican present sought to assimilate the turbulent insurrectionary tradition by removing it safely to an increasingly remote past.

Each of these new cities at the end of the century forged its own myths and lived off its own legends. But none of them depended, as before, on the totality of conception inherent in revolution. No mod-

ern author claimed the city as Balzac, Hugo and Flaubert, and Vallès and Zola once claimed it. The reconceptualization of the city brought new practices of urban space and new visions of revolution. The revolutionary tradition that Zola invoked so dramatically during the Dreyfus affair has no privileged space in the twentieth century. It is, rather, a sensibility, a consciousness, a set of abstract principles. The modern intellectual that Zola put into circulation does not write from or identify with a special place. No urban icon, no urban narrative can contain the principles of right and justice that guide the intellectual. Henceforth the intellectual who claims to speak for humanity does so disengaged from the particulars of time and place as a relatively disembodied figure.

For the century before, the interpretation of meaning meant Paris, and Paris arranged itself around revolution—revolution in its streets and revolution in its narratives. Making sense of the one always entailed making sense of the other. Indeed, the great works of this city and this time centered on that interaction and invariably reached for some larger form of integration. Over and over again, writers turned to place within a narrative of revolution to fix but also to convey the meaning of change in that movement. Paris was the subject; revolution, the inevitable theme.

By the end of the century, the virtuoso metaphor that served the urban imagination so long and so well served no longer. The cityscape disaggregated, and the bird's-eye view revealed not overall design but fragmentary scenes of almost unimaginable diversity. Zola's Paris made one final attempt to comprehend the city as a whole, but the knowledge came at a great price. This final Paris dissolved into a utopian vision of the future with little connection to the dynamic, revolutionary, and eminently visible cities of Hugo, Flaubert, Vallès, and even the young Zola. Like Zola in the articles on the Dreyfus affair, the intellectual of the twentieth century sees largely within the mind's eye.

Of course, Paris does not disappear from literature. On the contrary, in some senses the city is never more present. But, somewhere, early on, the twentieth century loses both the certainty that Paris can be known and the conviction that revolution holds the key to that knowledge. Writing the twentieth-century city implies different urban practices, entails very different strategies, and works with different symbols. Louis Aragon's marvelous Le Paysan de Paris (The Peasant of

Paris ) (1921 ), by way of example, takes on the city but in a decidedly surrealistic mode. Aragon works off the fragments of a public discourse (the signs and the advertisements in the Passage de l'Opéra, which he reproduces in loving detail), but he does not suppose any global coherence, much less one with revolutionary connotations.

The real coda to the myth of Paris comes with Raymond Queneau's Zazie dans le métro (1959). During the whirlwind Paris visit of Zazie, an inordinately precocious girl of eleven or twelve, even the most inveterate of her Parisian guides—a taxi driver—is never altogether sure whether he is looking at the Sacré-Coeur or the Invalides or the Panthéon (they all have domes), and there is always a sneaking suspicion that the building in question just might be the Gare de Lyon. Queneau's spoof of the modern guided tour to Paris also parodies the whole literary tradition of urban exploration. This Paris-Guide, or antiguide, for the twentieth century systematically effaces the historical and topographical differences crucial to the sense of history that informs the great urban narratives of the nineteenth century. At the same time, as parody, Zazie presupposes that history, that topography, and that tradition. The humor depends on the reader knowing that the monuments are from very different historical eras and are located in quite different parts of Paris. It also depends on catching the connections to Hugo's epic Les Misérables when Zazie is rescued from the police by her uncle's transvestite lover, who carries her through a sewer into the métro to the train station. For Hugo's christological Jean Valjean, who carries the wounded Marius through the sewers to his home in the city, Queneau gives us a complicated figure of uncertain meaning who takes Zazie out of, not into, the city.

Even the view from the top of the Eiffel Tower fails to make anything clearer since the only construction identifiable with certainty is the part of the subway that goes above ground. But that, as Zazie has already observed, is not the real métro. And the point is, obviously, that, because the métro is on strike, Zazie never gets to see the only thing that interests her in all Paris. In the one short trip that she actually takes on the métro, she faints and sees nothing.

Only the surfaces attract in Zazie. The depths of place have no meaning, no lessons to impart. The métro like the metropolis itself remains forever out of reach. Queneau explicitly refuses the mastery of the bird's-eye view and rejects the knowledge of the encompassing metaphor. We who live in the city are condemned and, like Zazie, live

without knowledge. What has she done, her mother asks on the train home, if she hasn't seen the métro? "I've aged," replies Zazie in the emblematic last line of the book, one that utterly resists the implicit notion of renewal in a revolutionary construct.

The coherence of the new, modern city derives from singular, private experience, from Queneau's fantasy that plays on even as it disavows the sense of the city as a whole. The faith that gave such assurance to the writers of the revolutionary tradition becomes just one more urban practice. Queneau celebrates not Paris but the absence of Paris. Finally, it makes no difference whether we are looking at Sacré-Coeur or the Invalides or the Panthéon. Gone are the time-space and especially the dream-time that made it possible to write the nineteenth-century city. Dreams, though, have a way of recurring, and they also have a life of their own.