Part One

1. Blood and Words

Writing History with (and about) Vampire Stories

The name of the bloodsucker superstition is Mumiani. I understand the superstition is fairly widespread throughout Africa. The Mombasa incident took place…in May or June [1947]. A man…started a story that the Fire Brigade were Mumiani people and had been seen walking around with buckets filled with blood, and had taken a woman as prisoner at the Fire Station with intent to take her blood. The man gave a good deal of detail, most of which I forget, but the gist of it was that Fire Brigade men took this woman while she was sleeping…off to the Fire Station.

The story ran round rapidly and aroused a great deal of excitement.…about noon on the day the rumours got started…the Municipal Native Affairs Officer heard the yarn, and…went to the Fire Station.…By that time excitement was rapidly rising.…Very soon after the MNAO’s arrival at the Fire Station a larger and angry mob gathered and started to get rough. Responsible Africans told the mob there was nothing in the story and certified they had searched the Station and found all in order. The mob refused to believe them. The MNAO with a few African police tried first to reason with the mob and then to disperse them. They were however heavily stoned and had to beat a rapid retreat…soon after an adequate force of police came up and after a few baton charges dispersed the crowd and made a few arrests. The excitement then rapidly subsided. The mob were roused in the first instance by their superstitious fears, and were soon reinforced by the rowdies who are far too numerous in Mombasa and always ready to join in any shindig.

The unfortunate Fire Brigade have I believe from time to time been suspected of Mumiani practices, because they wear black overalls, which are reputed to be similar to the dress of the alleged Mumiani men.

An African politician recalled that in 1952, a man returned to his home area in central Kenya, much to the surprise of his neighbors: “He had been missing since 1927. We thought he had been slaughtered by the Nairobi Fire Brigade between 1930–1940 for his blood, which we believed was taken for use by the Medical Department for the treatment of Europeans with anaemic diseases.” [2] In 1986, however, a man in western Kenya told my assistant and I that it was the police, not the firemen, who captured Africans (“ordinary people” just “associated firemen with bloodsucking because of the color of their equipment”) and kept their victims in pits beneath the police station.[3]

What are historians to do with such evidence? To European officials, these stories were proof of African superstition, and of the disorder that superstition so often caused. It was yet another groundless African belief, the details of which were not worth the recall of officials and observers. But to young Africans growing up in Kenya—or Tanganyika or Northern Rhodesia—in the 1930s, such practices were terrible but matter-of-fact events, noteworthy, as in the quotations above, only when proven to be false or when the details of the story required correction. In this book, I want to study these stories both as colonial stories and for their mass of often contested details. I want to interrogate and contextualize these stories for what was in them: I want to contextualize all their power, all their loose ends, and all their complicated understandings of firemen and equipment and anemia, so that they might be used as a primary source with which to write, and sometimes rewrite, the history of colonial East and Central Africa. I argue that it is the very inaccurate jumble of events and details in these stories that makes them such accurate historical sources: it is through the convoluted array of overalls and anemia that Africans described colonial power.

These were, as officials knew, widespread stories, which showed great similarities and considerable differences over a wide geographic and cultural area. Game rangers were said to capture Africans in colonial Northern Rhodesia; mine managers captured them in the Belgian Congo and kept them in pits. Firemen subdued Africans with injections in Kenya but with masks in Uganda. Africans captured by mumiani in colonial Tanganyika were hung upside down, their throats were cut, and their blood drained into huge buckets. How is the historian to tease meaning out of such tales? To dismiss them as fears and superstitions simply begs the question. To reduce them to anxieties—about colonialism, about technology, about health—strips them of their intensity and their detail. Indeed, to attempt to explain these stories, to show how they made sense of the world Africans experienced, would be to turn them into mechanistic African responses: it would reduce them to African misunderstandings of colonial interventions; it would be to argue that these stories simply deformed actual events and procedures. Such an analysis would turn the resulting history away from these stories and back to the events Africans somehow misunderstood.

This book takes these stories at face value, as everyday descriptions of extraordinary occurrences. My analysis is located firmly in the stories: they are about fire stations, injections, and overalls, and they record history with descriptions of fire stations and injections. These are tools with which to write colonial history. The power and uncertainty of these stories—no one knew exactly what Europeans did with African blood, but people were convinced that they took it—makes them an especially rich historical source, I think. They report the aggressive carelessness of colonial extractions and ascribe potent and intimate meanings to them. Some of the stories in this book locate pits in the small rooms of Nairobi prostitutes in the late 1920s. Others relocate the Tanganyikan Game Department in the rural areas of Northern Rhodesia in the early 1930s. Such confusions offer historians a glimpse of the world as seen by people who saw boundaries and bodies located and penetrated. The inaccuracies in these stories make them exceptionally reliable historical sources as well: they offer historians a way to see the world the way the storytellers did, as a world of vulnerability and unreasonable relationships. These stories of bloodsucking firemen or game rangers, pits and injections, allow historians a vision of colonial worlds replete with all the messy categories and meandering epistemologies many Africans used to describe the extractions and invasions with which they lived.

This book is not simply about rumor and gossip, however: it is about the world rumor and gossip reveals. The chapters in part 2 argue that such stories perhaps articulate and contextualize experience with greater accuracy than eyewitness accounts. They explain what was fearsome and why. New technologies and procedures did not have meaning because they were new or powerful, but because of how they articulated ideas about bodies and their place in the world, and because of the ways in which they reproduced older practices. The five chapters in part 3 write colonial history with vampire stories. The result is not a history of fears and fantasies, but a history of African cultural and intellectual life under colonial rule, and a substantial revision of the history of urban property in Nairobi, of wage labor in Northern Rhodesia and the Belgian Congo, of systems of sleeping-sickness control in colonial Northern Rhodesia, and of royal politics and nationalism in colonial Uganda. In each case, evidence derived from vampire stories offered a new set of questions, recast prevailing interpretations, and introduced analyses that allowed for a reworking of secondary materials. Vampire stories are like any other historical source; they change the way a historical reconstruction is done.

| • | • | • |

Siting Vampires

But why have I focused on these stories of blood? There are any number of other widespread rumors—about food additives that made men impotent, about dreams that foretold the appearance of white men, or dreams that foretold when they would vanish, about the origin of AIDS—that I could have used. But they do not share the same generic qualities and lack the similarities of plot and detail. Stories about colonial bloodsucking, in contrast, are told with—and about—a number of overlapping details; they are identifiable over a large geographic and cultural area, both by the people who tell them and the people who hear them, as a specific kind of story. Even people who don’t believe them understand that this is a particular kind of story and often use it as an example of what Africans are willing to believe, as chapters 4 and 8 argue. These stories are almost always taken together, so that they form a genre, a special kind of story that, while drawing on other kinds of stories and everyday experiences in each retelling, retains a specific set of plot and details. It is the pattern of the tale, not the circumstances of the telling, that makes a story recognizable as belonging to a genre, different from other stories that flourish alongside reports of bloodsucking firemen and game rangers.[4] As some of the oral material quoted in these introductory chapters makes clear, the circulation of the genre gives these stories their unity. These were the kinds of stories that, like some kinds of song or praise poetry, could be extended, amended, and applied and reapplied to different situations in different places.[5] Listeners understand the variety of these stories as forming part of a whole: hearing a bloodsucking story from Uganda can confirm a bloodsucking story from Nairobi. When someone hears that prostitutes work for firemen in Nairobi but not in Kampala, this does not contradict the story he or she knows. Instead, it underscores the local difference that makes the stories such accurate descriptions of life in Kampala and Nairobi. The circulation, and the differences circulation reveals, makes storytellers and listeners aware of the historical location of these stories, which in turn gives the genre its authority: a story that reports so many diverse experiences from so many different places must depict elements of social life—and speech—that hearers recognize and want to repeat.

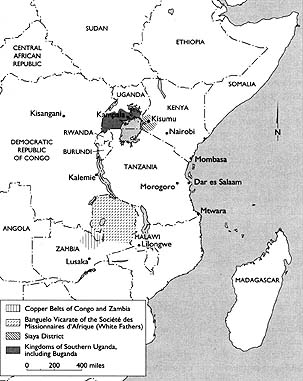

Map 1. East and Central Africa

Firemen, pits, injections, game rangers, and buckets—these are the formulaic elements of these stories. The formulaic has had a troubled history in the study of oral literature. Originally thought of as a group of words that expressed an essential idea, often in meter, formulas were once considered a key tool by which Homeric bards had composed their epics. But the idea was reworked, and by the time African history emerged as an object of academic study, the very fact that formulas were an explicit tool in performance was thought to make them less reliable as historical sources.[6] The devices of storytelling were considered irrelevant to the history as a story told. Recent research, however, has argued that African oral materials never provide the same kind of stable texts that documents do and has challenged historians to unfix the boundary between the formulas used to tell a particular story and the history transmitted in that story.[7] My use of the concept of formula in this book takes up that challenge, arguing that the formulaic elements of these stories, the firemen and the pits and the injections, are simply that: terms and images into which local meanings and details are inserted by their tellers. These stories say different things about injections and pits in different places because the history and the meaning of those terms is different in those places. These stories belong to a genre that is told with formulaic elements; they are about the past and can be used to recover experiences and ideas best described in terms of firemen, pits, and blood.

I call this transnational genre of African stories vampire stories, not because I want to insert a lively African oral genre into a European one, but because I want to use a widespread term that adequately conveys the mobility, the internationalism, and the economics of these colonial bloodsuckers. No other term depicts the ease with which bloodsucking beings cross boundaries, violate space, capture vulnerable men and women, and extract a precious bodily fluid from them. No other term conveys the racial differences encoded in one group’s need for another’s blood. Europe’s literary vampires were a separate race, which fed, slept, and reproduced differently from humans.[8] Yet I worry, as historians of Africa are prone to do, that an African specificity will be lost when I invoke a dominant European term. I worry that all the regional and local history in this book will be submerged into a vision of African vampires congruent with that of European lore. But in fact, some of the very processes of storytelling that inform this book should spare me further anxieties about which term to use: in contemporary usage, “vampire” conveys little of its original meaning. Popular versions of Transylvanian counts and modernized vampires reveal how powerfully a concept—and a word—can attract and hold events and ideas that were never part of its initial construction. The issue is not so much the accuracy of terms like “game ranger” or “firemen” but how such terms can be used to describe many situations. It is not a common point of origin that gives vampire beliefs their longevity and periodicity; as Nina Auerbach points out, “it is their variety that makes them survivors.” [9] Indeed, I hope that the very variety of colonial vampires in this book, and the variety of colonial situations they depict, will encourage others to look more carefully at the supernatural—the very term should encourage a careful rereading of what it might mean—and at Europe’s vampires. Far from being products of folk belief or a clear-cut representation of the extractions of a dominant power, vampire stories articulate relationships and offer historians a way into the disorderly terrain of life and experience in colonial societies.

| • | • | • |

Translating Vampires

There are no words in the languages of the people I write about for blood-drinker or blood-taker. The words in African languages that I translate as vampire are already translations—they are words for firemen, game rangers, or animal slaughterers that had already undergone semantic shifts to mean the employees of Europeans whose job it was to capture Africans and take their blood. This of course raises another question: were the practices of firemen and game rangers and surveyors such that they encouraged stories about bloodsucking, or did these terms mean vampire before the tasks of firemen and game rangers became well known? In short, which came first, the use of a term to describe an actual thing or job, or its use to mean vampire?

There is no simple, undialogic answer. One of the oldest terms for vampire on the East African coast, mumiani, first appeared in Swahili dictionaries in the late nineteenth century. According to Bishop Edward Steere’s dictionary of 1870, compiled on Zanzibar, mumyani was a mummy, but could also refer to medicine.[10] It had been a widespread belief in late nineteenth-century India, especially among plague victims on the west coast that hospitals were torture chambers designed to extract momiai, a medicine based on blood. The Indian Ocean trade, with African sailors coming and going between Zanzibar and India, could easily have carried the idea, as well as medicines supposedly made from blood, to East African markets.[11] Just over a decade later, Krapf’s dictionary, compiled near Mombasa, repeated Steere’s definition of mumiani, as the word was transcribed, but added “a fabulous medicine which the Europeans prepare, in the opinion of the natives, from the blood of man.” [12] No one I interviewed, however, said that mumiani appeared that early. Even people born in the 1890s said the practice started after World War I in Kenya and in the 1920s in Northern Rhodesia and Uganda.[13] It may be that some people on the East African coast in the late nineteenth century believed that Europeans made medicine from African blood, but their stories about it did not survive. But the term mumiani was in intermittent use on the coast for over a century, during which time it was given many of the contemporary meanings associated with blood accusations. In the Swahili-French dictionary of the priest Charles Sacleux, compiled on Zanzibar and published in 1941, mumiani is defined as mummy, and a medicine Africans believed was made from dried blood. Jews, Sacleux added, were in charge of getting the blood from people.[14] In everyday use, mumiani was synonymous with kachinja and chinjachinja. This Swahili term came from the verb kuchinja, to slaughter animals by cutting their throats and draining their blood. Doubling the root word intensified its meaning. The prefix ka- meant small in Kenya and gross in Tanganyika. Either or both meanings may have applied when the term was fixed in everyday use.[15] However, the term for slaughtering people, according to A. C. Madan’s 1902 English-to-Swahili dictionary, was a literal translation word that meant the killing of many people (from the verb kuua, to kill) that did not use the root -chinja.[16] The use of a term specific to animals for vampires may have kept the idea of bloodsucking outside of all logic and nature. Indeed, animal butchers were not accused of bloodsucking on the East African coast: firemen were.

The word for firemen, wazimamoto in Swahili (bazimamoto in Luganda), is a literal translation: the men (wa-) who extinguish (from kuzima to put out, to extinguish) the fire or the heat (moto). It became a generic term for vampire, always as a plural, almost as soon as it was in widespread use, well before there were formal fire brigades in most of the places where the word meant vampire. In Uganda, for example, the idea that bazimamoto took Africans’ blood predated full-time firemen by thirty years. Chapters 4 and 7 explore the loose relationship between occupational practices and the social imagination, but the fact that there were no real firemen meant that the term could be applied to surveyors, yellow fever department personnel, whomever. It is not that the term had no specificity, but that its meaning was unstable enough to be made to fit any number of situations and relationships. The term banyama (singular, munyama) for game rangers in colonial Northern Rhodesia was translated by officials there as “vampire” as early as 1931. Not only did it refer to the game department in a neighboring colony, but it was another term depicting actions toward animals applied to humans. The word was never fully translated into Bemba, the local language. The prefix ba- means men, but nyama is Swahili and Nyanja for the meat of animals and quadrupeds who shed blood, either in sacrifice or as predators: cows have nyama but chickens do not. The Bemba word is nama.[17]Although the term does not seem to have been used in Swahili-speaking areas, banyama maintained its Swahili origins for Bemba speakers; it was never naturalized in the local language. Many words for vampires were never given African translations. Among the Nilotic Luo peoples of western Kenya, the word for vampire was the Swahili plural wachinjaji, slaughterers, and not a Luo translation. In Mozambique, the term was Portuguese, chupa-sangue, literally “blood drinker or blood sucker,” although Swahili speakers would note the implicit pun that chupa means bottle in Swahili, a word derived from the Portuguese chupar, to suck or drain.

The pun I impute to chupa-sangue raises another question. When we speak of words used by people who neither read nor write, how useful are terms like “translation,” and “pun,” or even “multiple meanings”? Are we not better served by asking what kind of understandings speakers bring to bear on their own use of these words? The term for those who captured Africans for the Europeans who ate their flesh in colonial Belgian Congo was batumbula (singular, mutumbula), from the Luba -tumbula, translated in Shaba Swahili as to “butcher.” [18] (Shaba Swahili is the variant of the Swahili of the East African coast spoken in present-day Shaba, colonial Katanga, shaped as much by work and migrancy in the area as it was by its historical roots as a trade language.) But the range of meanings for the root tumbula in the region suggest how accurately the term came to describe all the things batumbula did. In Luba, -tumbula means “to overpower,” but also “to pierce or to puncture,” sometimes from below.[19] In many of the languages of Kenya and Tanzania, including Swahili, the meaning is “to disembowel” or “to make a hole with a knife or sharp object.” [20]Batumbula, a term that took hold among the migrant labor population of the mines of colonial Katanga, may have been heard by Swahili speakers with one set of meanings and by Luba speakers with another set. The power and viability of the term lay in its many meanings, which allowed the word to encompass all the things batumbula were said to do, from digging pits, to giving their victims injections, to eating their flesh. And in colonial Belgian Congo, batumbula was also glossed by the Shaba Swahili term simba bulaya, the lion from Europe, another animal term to describe the predatory cannibals who left their victims’ clothes behind.

Why are there so many terms that could mean “bloodsucker”? And why do so many of them describe another activity altogether? Such semantic shifts occur when existing languages do not have the words to convey new meanings. But the fact that wazimamoto meant “vampire” almost as soon as it became a word suggests that these words were semantically malleable: once in everyday use, they could be taken over by their users and given new and potent meanings. They did not simply describe firemen the way a new word might describe a streetcar or an airplane; they described firemen and what Africans thought they really did.[21] The words for firemen and game rangers and small butchers themselves were translated by Africans to describe true meanings not available in the language from which they are taken. Vampires were new. Despite scattered written references and a dictionary definition, no one I ever interviewed knew any precolonial stories about whites or Africans who took blood: “In those days there was nobody looking for blood.” [22] The blood of precolonial sacrifice was bovine; the ritual killings that sometimes marked a king’s death did not draw blood, and the blood of blood brotherhood was thought of as a sexual fluid, more akin to breast milk or semen than to the blood of wounds and injuries.[23] But why do some of these terms require two languages to contain their meanings? Part of the reason is again semantic: blood was not a stable enough category to allow for a local term to describe its extraction. Many African peoples do not have a specific concept for blood that matches the scientific concept of a fluid pumped by the heart into arteries and veins. Many African peoples use a word for blood broadly as a metaphor for sexual fluids, either because of symbolic systems or because of the demands of polite conversation. At the same time, many African languages distinguish between kinds of blood and the circumstances in which it leaves the body in ways that the scientific concept does not, so that the blood of childbirth and the blood of wounds are called by different terms.[24] The red fluid circulating through the body was in some places an alien concept, best described by the Portuguese word sangue or by using a term derived from the verb kuchinja. But different conceptions of the body do not explain why some words never fully became Bemba or why Luo speakers use a Swahili word without translation. The absence of linguistic transformations, however, may be less semantic than genealogical: each plural, and each language carries a historical link to the source of the term. The term never becomes fully Bemba, or Luo, because part of its importance lies in its origin, part of its local meaning is its very foreignness.[25] And throughout this book I shall use wazimamoto, mumiani, kachinja, banyama, and batumbula as synonyms for “vampire,” and vice versa: cultural literacy, like translation, is a two-way street.

Many of the published accounts of vampires have been memoirs: an author encountered the rumor, wrote about it, and theorized its meaning. Only Rik Ceyssens, in an encyclopedic article on batumbula in the Congo, argues that these stories can be traced to the sixteenth century and the slave trade. He relates stories of consumed Africans to precolonial African ideas about agricultural cycles and commodity production. According to Ceyssens, batumbula stories from World War II Kananga and Katanga, for example, were but modern versions of eighteenth-century slaves’ beliefs that they were being transported to the New World to be eaten; he is more concerned with the continuity of African ideas than with the ways in which 1940s batumbula stories described the industrial spaces of the urban Congo.[26] Ceyssens flattens a variety of descriptions of consumption into ingestion and levels much of the sense of region that I try to make prominent in this book. The white cannibals of the slave trade and the white cannibals who captured the imagination of Congolese after the fall of Belgium during World War II were constructed in different social worlds. The tales told by slaves on the Atlantic coast and tales told by fishermen in the Luapula River Valley four hundred years later are not the same. While the idea of cannibalism informs these stories, the white people in each set of narratives have different meanings, different relevances, and different histories. Among Kongo-speaking people in and around Kinshasa and near the Atlantic coast, white people are ancestors and the Americas are the other world inhabited by the dead; the white mine supervisors and priests of Katanga batumbula stories carry quite different connotations; the Americans whose arrival was promised by the Watchtower movement in the 1930s and 1940s had different meanings still.[27] Stories of white cannibals, however similar in plot, are shaped by local concerns and local experiences; stories may travel, but they do not travel through or to passive storytellers. Interpreting stories as regional productions reveals them to be both socially constructed and socially situated; locating such stories in regional histories and regional economies yields historical evidence.[28]

Most of the people I have interviewed—and I have now interviewed about 130—say that white vampires began their work between 1918 and 1925. It seems likely that these stories were triggered by Africans’ experiences during World War I, but that does not explain their meaning over the next forty years, during which time they came and went with dreadful intensity. Not every African believed these stories, of course, and many people assumed that those who did simply misunderstood Western medicine. A Ugandan politician complained that vampire beliefs were a troubling kind of popular nonsense: “My people the Baganda had strange ideas about the British. They thought they drank blood and killed children because they did not understand what happened in hospitals.” [29] A Tanzanian man said that “the British government needed no blood donations because it got blood in this way, but when independence came this government stopped it. That’s why hospitals always ask people to volunteer to give blood.” [30] A man in western Kenya explained that once he realized that “nowadays people are required to donate blood for sick relatives,” he began to “strongly believe” that wazimamoto stories actually described “the science of blood donation.” [31] Misunderstandings or not, these stories presented grim ideas about knowledge, expertise, and therapeutic and political power: “These people were educated in the use of blood, they knew about the use of blood.” [32] In colonial Northern Rhodesia, banyama had “white balls of drugs” that could sap their victims’ wills and, a few years later, butterfly nets that could expand to capture a grown man. In Kenya, the men who worked for wazimamoto were “skilled.” Jobs gave people new tools with new powers. In Uganda, some men said the bazimamoto were really health inspectors or the yellow fever department; in Tanganyika in the 1950s, others said that firemen had injections that made people “lazy and unable to do anything.” [33] Not only did prostitutes in Nairobi dig pits in their small rooms in which to trap their customers for the wazimamoto, the fire station in Nairobi and the police station also had such pits, hidden from public view by clever construction.

Many authors have speculated on how these stories began. An administrator with many years experience in Tanganyika wrote that mumiani was simply the theory by which Africans explained their invasion first by Arabs and then by Europeans. It kept their dignity intact. The Arabs were said to have killed Africans for the blood, which they made into medicine that they drank or smeared on their weapons. “It was this that gave them power over Africans.” [34] Stories about white people taking precious fluids from the peoples they colonized were common in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Peter Pels has written an intriguing article in which he argues that mumiani stories were actually carried from India by soldiers in the 1890s, a decade after Krapf’s dictionary. Drawing on David Arnold’s work on epidemic disease in nineteenth-century India, Pels notes some similarities between Indian ideas about momiyai—a medicine made from bitumen, but said to be made from blood—and African ideas about mumiani. The similarity is too much to explain by the colonial experience, and Pels suggests that Indians’ fear that sick people were brought to hospitals specifically to have momiyai removed from them was carried to East Africa by the sepoys recruited in Delhi in the early 1890s for the East African Rifles. In 1895, the East African Rifles—700 soldiers, of whom 300 were Indian—were quartered in Mombasa; 400 Indian sepoys joined them in 1902. Pels suggests the rumor spread through conversations between these African and Indian soldiers or via the Gujurati shopkeepers he places in East Africa somewhat earlier than most sources do. A single letter to the Tanganyikan secretariat stating that the rumor began in Mombasa in 1906—at the house of a Parsee no less—was confirmation.[35] According to Pels, nothing in Africans’ experience of colonial rule generated these stories.

This book argues something very different. I think there are many obvious reasons why Africans might have thought that colonial powers took precious substances from African bodies, and I doubt if Africans needed to see or hear of a specific medical procedure to imagine that white people would hang them upside down and drain their blood. I think bloodsucking by public employees is a fairly obvious metaphor for state-sponsored extractions, just as vampires are an unusually convincing modern metaphor for psychic ills and personal evil. While I think that vampire beliefs emerged out of witch beliefs—Africans, after all, did not make up these stories out of thin air—what is significant is that these particular beliefs were new. Even witchcraft did not describe what Africans were talking about when they talked about vampires. My concern is not with why the idea of bloodsucking Europeans came into being, but why it took the hold it did, and why Africans used it to depict a wide variety of situations and structures and sometimes acted upon such beliefs. As a historian, I am less concerned with the origin of vampire beliefs than I am with their power, their ability to describe and articulate African concerns over a wide cultural and geographic area.

Even if these stories were originally “brought” there by Indian soldiers garrisoned in East Africa, this does not explain the meanings they had in East Africa fifty years later. Even if these beliefs could be traced to the botched and badly done battlefield medical practices in wartime, or bismuth injections for yaws a few years later, this would not explain why some Nairobi prostitutes were accused of capturing men for the firemen, and why some white doctors, some surveyors, and some policemen were accused of being vampires. The origin of the belief does not explain how these stories came and went, capable each time of describing new situations and relationships. As one Ugandan official told another, the rumor was dormant for a few years “and then something starts it off and for the next few months it’s more than your life’s worth to stop your car for a pee.” [36] It is not a common point of origin that gives vampire beliefs their longevity and periodicity, but how elastic they are, and how broad a category “vampire” is.

The question of how and what to think about imagined events and deeds has long concerned historians. Recent debates about what constitutes “experience”—discussed below—have long genealogies: theological debates in Western Europe—including debates about witchcraft accusations and confessions—were also concerned with questions of memory, corporeality, and proof. In the next few pages I want to explore some questions of evidence raised by the literature on witch beliefs both in Europe and in Africa as a way to both suggest points of origin for African vampire rumors and the vocabularies with which vampires are described.

In a book that was far more influential to historians of Europe than it was to be to historians of Africa, E. E. Evans-Pritchard argued that witch beliefs were not superstitions, but explanations. Witch beliefs did not deny accidents or bad luck or illness, they simply explained why an accident or bad luck or an illness happened to one person and not another. His example of the granary is worth repeating: when a granary fell in the afternoon, collapsing on the men taking shade beneath it, no one questioned that this was due to the termites eating through the poles on which it stood. At the same time, however, no one thought it possible that it had fallen at the precise moment it did without some supernatural intervention: why else did it fall in the daytime, on these men and not on others? Witch beliefs explain the specificity of cause far better than Western explanations of termites do.[37] Years later, Monica Wilson noted that scientific medicine could easily be accommodated to witch beliefs: “I know typhus is caused by lice,” said her assistant, “but who sent the lice?” [38]

Fifteen years after Evans-Pritchard, anthropologists working in Africa began to argue for a sociological interpretation of witchcraft. Suspicions and gossip about witchcraft revealed social tensions, while public accusations of witchcraft revealed social conflict.[39] These anthropologists had for years focused on the way witchcraft is an idiom of intimacy: a person has another bewitched because he or she has been wronged by the other person. A brother slighted in a returned migrant’s gift-giving, a co-wife insulted, or a man impoverished as his neighbor grows rich—these are the people who want to bewitch their offenders. The other horrible things witches did—going naked in daytime, consorting with hyenas and snakes, ingesting what normal people would never touch—amplified the ways that witches inverted everyday life and made it all the more appalling that they harmed those closest to them.[40] The diverse places of intimate socializing—births, for example, or beer parties—are likely to attract witches.[41] For these anthropologists, witchcraft was a way for people to articulate, and sometimes act out, the tensions inherent in specific social structures. Witchcraft was not a system of explanation or phenomenology, but embedded in social structure and social history.[42] Among the Nupe, where women were witches and a few men had the innate power to deal with witches, fatal witchcraft was attributed to the men who had betrayed their gender and failed to constrain witchcraft.[43] Sally Falk Moore argues that witchcraft accusations followed specific patterns for specific reasons, such as when the wife of a middle brother was accused of bewitching her childless sister-in-law. The weak middle brother, already working in town, could not combat the accusation; he lost use rights over his land when his wife left it. The older brother, husband of the childless woman, claimed the land for his farm.[44]

Colonial capitalism does not seem to have made witchcraft any less intimate, but there are hints from after 1920 that witch beliefs were being refashioned. Edwin Ardener’s description of a world of witches and animated corpses at work in hilltop plantations in post–World War I Cameroon placed imaginary beings in the context of economic change. Witch beliefs had continuity but were not constant: a witch finder could cleanse an area of witches so that ordinary people would be safe getting rich from cash-crop production.[45] John Middleton was told that in Lugbara in northern Uganda around 1930, sorcerers who had once been migrants purchased medicines with money and “wandered aimlessly, filled with malice” killing strangers.[46] Among the Bashu in eastern Belgian Congo in the late 1950s, dispersed lineage-based villages had been consolidated just as male migrancy had coincided with the introduction of cassava, both of which increased female labor dramatically. A new kind of witch—women who taught other women to leave their bodies and punish the men with whom they were angry—became a new source of misfortune by the end of the colonial era.[47] Witches were said to be aged in postcolonial Zambia; the crones and the old men thought to be witches suggested the true burdens of kinship obligations for sons and nephews, and in postcolonial Cameroon, the victims of witches were sent to work on the invisible plantations of great men.[48]

New and improved witches did not translate into vampires, however, in either 1930s Lugbara or postcolonial Cameroon. My question, then, is why weren’t the surveyors, the Parsees, or the firemen visible in East Africa before 1925 called witches? They could have at least been described as these new types of witches of the post–World War I era, but these people said to be looking for blood were called game rangers or firemen instead. The reason in part was that they were strangers for whom an idiom that conveyed the intimacies and the disappointments of closeness would have been inappropriate. It would have stripped these agents of the state of all that made them foreign and powerful. Vampires were not thought to be social problems—the result of envy and asocial behavior; they were considered political realities. Although chapters 4 and 5 argue that vampire stories articulate new African social relations in a colonial context, when Africans spoke about vampires—their hired agents, their cars, and the spaces in which they worked—they described political issues in a situation that was categorically different from the tensions between siblings, co-wives, and matrilineal kin. If beer parties had been sites for witchcraft, people in Uganda said that bazimamoto captured men after a night’s drinking, as they staggered home alone. If witches sought the intimate fluids of birth, Congolese batumbula, at least, avoided parturient women. Vampires were more than new imaginings for new times, they were new imaginings for new relationships.[49] I do not mean to suggest a mechanistic connection between social events and social imaginings, however; there is another possible reason why vampire beliefs emerged out of witch beliefs, and I want to turn to European historiography to discuss it.

Europeanists have taken issues of witchcraft and witch hunting very seriously, and in doing so, they have raised some of the questions of evidence that have informed this book. Studies of witchcraft and particularly witchcraft accusations and confessions in Europe have long noted how similar witches’ confessions were. If there was no such thing as a devil, and if witchhunting was a crazed moment in European history, why were the details of witchcraft—the sabbath, the spells, the familiars—so similar over a wide geographical range? Margaret Murray and in a much more subtle way Carlo Ginzburg have argued that witches’ testimony revealed another world altogether: that not of witchcraft but of an older religion of female and agricultural fertility, of shamans and trances. In between Murray and Ginzburg, Norman Cohn wrote an extremely influential account of European witchhunting in which he argued that the sabbaths, trances, and familiars were the imaginings of the inquisitors, who then used torture to shape the answers they wanted and got. All these analyses are framed around either/or terms, however: the narrative of witchcraft in all its rich details either belongs to the common folk or to the inquisitors. These analyses argue that there was no shared vocabulary with which peasant women and clergymen negotiated a description of the world, no genre of talking that both parties might use to different ends.

But shared vocabulary is a tricky concept: knowing the words and using them correctly were very different things. Some vocabularies and their deployment were so far apart that confessions were difficult to obtain. Po-chia Hsia’s studies of the blood libel note that the obsessions and fears of ordinary Christian folk were translated to clergymen with great speed and clarity; accusations of Jewish ritual murder began with parents telling judges that their missing children had been slaughtered by Jews. But even under torture, in trials that were conducted in two or three languages, Jews who only vaguely knew the stories Christians told about them could not always produce a description of Jewish ritual murder that satisfied their inquisitors. In late fifteenth-century Germany, tortured Jews tried in painful confusion to explain why Jews needed Christian blood—to cure epilepsy or for its healing power. To this the judges answered: “Then why is your son an epileptic?” and “we would not be satisfied.” [50] Other vocabularies had to be learned and negotiated. When inquisitors in Friuli first heard people confess willingly that their spirits went out at night to guard crops from witches, they did not know what to call these benandanti. Were they witches or counterwitches? Inquisitors had to coin a new phrase, “ benadanti witch,” to begin to evaluate the information they heard. It took seventy years for benadanti to come to mean witch for both peasants and inquisitors, and even then both parties were uneasy about what kind of witch it meant.[51] In some places and instances, vocabularies were so consistent that women and theologians made concerns about the harvest, food, and nurturance central to women’s everyday lives and the most intense images of Christian piety.[52] Scholars have argued that in early modern Germany, women appropriated the inquisitors’ version of witch beliefs to describe the conflicts and disappointments of their own domestic situation.[53] So shared was this vocabulary in some communities that some accused witches begged forgiveness after their confessions, and others, unrepentant in death, were said to have paralyzed the hands of the executioners attempting to carry out death sentences.[54]

It is with these varieties of vocabularies and the multiplicity of insinuated meanings that historians of witches and vampires work. It is precisely these difficulties of translation—the years when benadanti did not mean witch, the ignorance of Bavarian Jews of what their accusers said about them, all the men who could be called wazimamoto—that describe the world as people in the past saw it, with all the variations that inequalities of power and knowledge bring to such descriptions. The power relations in an interview done in rural Africa, or a judge’s chamber in Friuli, may not shape the content of testimony; there may be no simple one-to-one relationship between a question asked and the answer received, let alone between the relative authorities of interrogator and speaker. Here Hayden White’s analogy of the historian and the psychiatrist is useful, partly because it allows for the loose and slippery ways that information is presented, but mainly because it focuses on how historians reevaluate the information they receive. Historians foreground some meanings and submerge others to authorize an interpretation of the past. Rather than seeking a reality behind the words and images—the task of judges and inquisitors—historians’ reorganization gives some meanings great and renewed power and strips others of their intensity. Ginzburg reflected on Nightbattles that inquisitors and ethnographers simply recoded peasant belief. But however much coding and recoding the interrogator does, the terminology remains that of the informant, and those vocabularies dominate the resulting texts. My point is not that the term benandanti was contested—it was, but that hardly matters for what follows—but that talk about benandanti could only be conducted by using the term. The deep cultural layers constituting the term could be maintained by the speakers even while it eluded the judges; the judges could only access the layers of historical and cultural meaning by using the term. In this way, some of the most powerful evidence in this book comes from Europeans’ accounts of African vampires: they didn’t believe them and often published them to show the depth of African superstition, but they presented these stories in all the rich contradictory details of the genre; they wrote with materials and constructions they themselves did not produce. Like Friulian inquisitors, historians do not reject information out of hand; rather, they rearrange it, stressing different parts according to their own interests and understandings of the world: the gap between the “spontaneous confessions” (Ginzburg’s term) and interrogators expectations is never fully bridged, and terms are never fully recoded by power or culture. For fifty years the judges heard stories of benandanti and could not figure out what the term actually meant. When the confusion was over, when inquisitors and peasants began to speak the same language, benandanti meant witch, but inquisitors now used the term. The array of meanings of benandante—or mumiani, or banyama—could not be fully stifled; judges and officials could never really recode local beliefs.

In wartime colonial Northern Rhodesia, when European officials were thin on the ground, African clerks, settlers, and colonial officials sought to recode banyama into traditional African human sacrifice, which, they claimed, had gone on for centuries. “The old word used before the advent of the Europeans,” mafyeka, which had appeared only once in official writings on banyama,[55] became the subject of memoranda in Northern Province for almost two years. A man was attacked on a path in Isoka District in 1943. When the man’s assailants claimed they were only after a reward from banyama, the district commissioner, Gervas Clay, turned to Robert, the African district clerk, for clarification. Robert told him that in addition to banyama, there were mafyeka, people who sacrificed Africans at Christmas in a chief’s village. The victims’ blood was sprinkled on a drum used in rain-making ceremonies.[56] Africans believed that Europeans approved of this custom, Robert said. Clay sent for the relevant files and studied the fragments about banyama he found, recoding them with his new insider knowledge: “I would suggest the possibility that the activities of the Mafyeka…may not be dead and the whole banyama story may be an invention of those who wish to keep mafyeka activities alive.” Most banyama incidents took place in the rainy season; those that did not were due to “the natural delay” in reports of such disappearances.[57] Although Clay and his wife had filmed the rain dance the year before and found it “completely harmless and rather dull,” two African policemen were sent to observe the ceremony in 1943. They found much that was ominous: “the noise of the drum is different from an ordinary drum, and seems to be made by rubbing rather than beating” and dancers wore red and looked very serious. Clay recommended that the assailants be convicted of attempted murder, to allay African suspicions of European collusion.[58]

A few months later, R. S. Jeffreys, a retired official, wrote an unsolicited letter to the district headquarters (the boma) in Northern Province, explaining that a chance meeting had alerted him to officials’ need for clarification regarding human sacrifice. Recalling that he “really knew these people” and “their dialect” when he lived in Isoka twenty years ago, he noted that kidnapping and killing by strangulation during the early rains of November was “the observance of customary propitiary rites for the securing of an abundant harvest. ” He did not use the term mafyeka, but assured officials that the custom still went on, albeit in great secrecy.[59] Ten days later, the provincial commissioner issued a memorandum to all DCs in which he transformed banyama into ritual murder and a harvest ritual: the word mafyeka had disappeared altogether, and banyama had become “the so-called banyama movement,” which attempted “to obtain people for human sacrifice in connection with rain making ceremonies or to ensure good crops.” A retired African clerk “of the highest integrity” had described the commonplace methods of sacrifice.[60] The letter from Jeffreys was typed (with several carbon copies) and filed, and, over the next few years, copies were sent around to various officials and anthropologists at the Rhodes-Livingstone Institute requesting figures on the frequency of ritual murder in the colony.[61] But mafyeka and the recoding of banyama were short-lived; outside of these memoranda, the term was never used. Even as officials proclaimed the new meaning of banyama, they forbade a London parasitologist to collect stool, blood, and skin samples for fear he would be accused of being banyama.[62] By 1945, the word mafyeka was gone and only the acting chief secretary, Cartmel-Robinson, himself accused of being banyama during a smallpox vaccination campaign in Isoka in 1933, defined banyama as meaning human sacrifice.[63] No one else did. Earlier in the year, the PC of Northern Province assured two settlers that banyama was an African superstition of no historical validity and that they should advise their laborers accordingly.[64]

But vampires, witchcraft, and ritual murder were, in Gábor Klaniczay’s words, “a matter of mentality and legal practice.” The place of proof in witchcraft and banyama trials and the place of popular lore in articulating that proof was not simply how the accused were convicted; it was the site in which the many meanings of terms for witch were disclosed and forced into official usage. In a very important essay, Klaniczay locates in the emergence of “vampire scandals” in the Austro-Hungarian Empire starting in the seventeenth century—“the first media event” according to Paul Barber[65]—in the decline in prosecutions for witchcraft there. The many meanings of witch could not survive the newly scientized appeal courts of Maria Theresa’s reign, and the very facts by which vampires were separated from ordinary witches meant that vampires could never be fully investigated; they could only be condemned as superstition and refuted. Vampires straddled the realms of nocturnal bloodsucking beings and biological knowledge in which blood was an object of investigation in and of itself. The new vampire that emerged in the Balkans was categorically different from the bloodsucking entities that had gone before. It was dead, and in rising from the dead, it was a dreadful parody of Christ. Vampires were a very special kind of corpse, they never decayed; they rose from the grave only to have carnal relations or take blood. The blood they took was not a generalized bodily fluid that might be blood, milk, or semen, however: it was a specific red fluid that vampires took from the veins in which it circulated in the bodies of the living. Vampires were very much a product of modern theories of the body. Prosecution of vampires raised far more problems than it would have solved; they remained outside official sanction and in a relatively short time became a literary idiom, mixed with—then as now—spectacular fantasies of sexuality and death.[66] However novel eighteenth-century Balkan vampires were, they could easily be bundled with older ideas about race and blood, so that Balkan vampires and Jewish ritual murder could sometimes be combined. Vampires troubled the tenets of scientific humanism: a belief in vampires insisted that difference did matter, so that the specificity of vampires could be associated with the specificity of Jews.[67] These associations did not make vampires any more or any less real, but it made them both a metaphor and a belief at the same time. The accusation in 1880s London that Jack the Ripper was a Jew in search of Christian blood must be read alongside newspaper editorials from the same year that referred to Jewish immigrant merchants in London as vampires.[68]

I do not want to force Klaniczay’s subtle analysis onto East and Central Africa, but further research might be able to look for the origin of colonial vampires in the banning of the poison ordeal in colonial Africa.[69] I do not wish to imply that vampires rise up whenever witches go uncriminalized, but rather that without the public spectacle of ordeals—like trials—the many things witches mean are not formally debated and contested. African vampires came to be talked about differently, in different contexts: they were a synthetic image, a new idiom for new times, constructed in part from ideas about witchcraft and in part from ideas about colonialism. These vampires might move about at night, but they did not go naked: they wore identifiable uniforms and used the equipment of Western medicine. Witches and vampires were different because they operated in different historical contexts. Vampires were a discursive contradiction—firmly embedded in local beliefs and constructions but named in such a way that their outsiderness was foregrounded. Unlike witches, vampires were not deeply rooted in local society; they did not fly or travel on familiars, but had mechanized mobility. Bloodsucking firemen had none of the personal malice of witches; it was a job. As such, it did not merely imperil people in tense relationships, it imperiled everyone. Firemen and their agents were not evil but in need of money. “Wazimamoto employed prostitutes…they did this for the money, they needed the money, and they could do this kind of work.” [70] “If somebody asked you to look for a drum or a liter of blood for 50,000/-, would you not do that?” [71] “It was not an open job for anybody, you had to be a friend of somebody in the government, and it was top secret, and it was not easy to recruit anybody…although it was well paid.” [72] Vampires were outside the social context that witches continued to inhabit in East and Central Africa; they were seen to be internationalized, professionalized, supervised, and commodifying.

Still, why did Africans, or anyone else, articulate tensions and conflicts with stories of bloodsucking beings? Vampires, Klaniczay argues, straddle the connections between medicine and violence, between the supernatural and new scientific rationalities that were becoming naturalized. They were a way of talking about the world that both parodied the new technologies and showed the true intent behind their use. The very novelty of blood and the very detailed ways Africans said it was extracted provide a powerful way to talk about ideas and relationships that begged description.[73] It is not that there were no other ways for Africans, or Transylvanians, to talk about wealthy men or new machines or the meaning of medical testing, but that these things were so important that they were talked about with new, specific vocabularies.

| • | • | • |

Truth in Vampires, Truth in Oral History

A simple premise undergirds my interpretation of vampire stories in this book: people do not speak with truth, with a concept of the accurate description of what they saw, to say what they mean, but they construct and repeat stories that carry the values and meanings that most forcibly get their points across. People do not always speak from experience—even when that is considered the most accurate kind of information—but speak with stories that circulate to explain what happened.

This is not to say that people deliberately tell false stories. The distinction between true and false stories may be an important one for historians, but for people engaged in contentious arguments, explanations, and descriptions, sometimes presenting themselves as experts, or just in the best possible light, it may not matter: people want to tell stories that work, stories that convey ideas and points. When Gregory Sseluwagi in Uganda became exasperated with my assistant and I hectoring him to admit that vampires did not exist, he said, “They existed as stories,” and it was that existence with which he and his fellows were confronted daily.[74] For this man—and for historians—true and false are historical and cultural constructions. They are not absolutes but the product of lived experience, of thought and reflection, of hard evidence. “During the colonial period, I could not believe there were some people who could abduct people. I would ask myself, how could someone go missing? Could somebody disappear like a goat? But when I learned of my brother-in-law…taken by the Amin regime…then I understood. But for some of us, who did not know anybody captured by bazimamoto, it was impossible to understand it.” [75]

For most of the people quoted in this book, experience was true, but not as reliable as hearsay, the circulating stories that helped a person understand what had previously been incomprehensible. There was a widespread belief that talk was rigorously grounded in fact. Its opposite was the “loose talk” that characterized the Swahili-speaking people of the East African coast.[76] Children were brought up not to speculate idly.[77] The way to prove that vampires were real was to say so: “This is not just a tale, nor something you gossip about,” the Congolese painter Tshibumba told Johannes Fabian.[78] Experience shaped narratives insofar as it was assumed that everyone spoke the truth. “If I am stealing bananas and they talk about me, they say I always steal bananas. But can they talk about somebody they don’t know, and say he is stealing?…Now I have seen this recording machine. If I had not seen it, I wouldn’t be able to talk about it, but because I have seen it I can talk about it.” [79] Put simply, “people were not crazy just to start talking about something that was not already there.” [80] The issue was not how well argued a story was—what Paul Veyne has called “rhetorical truth,” established by eloquence and elegance[81]—but how readily and commonly a story was told. “It was a true story because it was known by many people and many people talked about it. Therefore it is a true story and it is wrong to say that it is not because they would not talk about it if it was not true.” [82]

But how well can oral historians trust informants to talk about what’s true, especially if, as I argue, what is true is so historically constructed as to be beyond generalization. Some believe that, like trial lawyers, oral historians should not ask leading questions to elicit facts that can be evaluated on their own terms to arrive at a single truth explaining one version of events. Interviewers must be neutral; otherwise they risk people telling them the stories they think the interviewers want to hear. Jan Vansina has cautioned against leading questions with a calculus of participation and exclusion: “Any interview has two authors: the performer and the researcher. The input of the latter should be minimal.…Indeed, if the questions are leading questions, such as ‘Is it not true that . . .’ the performer’s input tends to be zero.” [83] This book argues something very different, that absolute notions of true and false, of interviewing technique and legalistic practices, are simply overwhelmed by local ideas about evidence, ideas that are continually negotiated and renegotiated by talking.[84] In the following exchange, who is leading whom, the way informant and interviewer toss concerns about expertise and knowledge back and forth, indicate the ways in which evidence, especially oral evidence, is produced in contentious dialogue:

q:Some people have told us that wazimamoto kept their victims in pits. Did you ever hear this?

a:No, I never heard anything like that.

q:Some people have said that wazimamoto used prostitutes to help them get victims. Did you hear that also?

a:Yes, I heard that wazimamoto used prostitutes for such purposes.

q:That means these stories were true?

a:Of course they were. Who told you they weren’t?

q:Nobody told me, it was just my personal feeling that these stories were false.

a:These stories were very much true. Those stories started in Nairobi when racial segregation was there. Whites never shared anything with other races and whites were also eating in their own hotels like Muthiaga.[85]

The slippage between confirming facts, hearsay, and geographical knowledge bordering on political economy is typical of wazimamoto stories told by former migrants in western Kenya. But the slippage also poses a disjuncture between academic historians’ and the speakers’ notions of truth. While historians might be most concerned with which parts of the account are true and are thus useful in historical reconstruction, the speakers seem engaged in problematizing what is true, and establishing how and with what evidence a story becomes true. It is not that truth is fluid, but that it has to be established by continually listening to and evaluating new evidence. The material basis of historical truth is not eroded in such accounts, and the mediation of language is no stronger than the events it describes. Something much more subtle is going on, something oral historians may be better placed than other historians to appreciate, that the use of language is the analysis by which people ascertain what is true and what is false, what they should fear and what they can profit from. It is through talking that people learn about cause and intention. Language and event—even language and événement—are not opposites, but in constant dialogue and interrogation. Accounts of the past are documented with words, with descriptions of social relations and of material objects, even as the relationships between the men and women narrating these accounts are negotiated as they speak.[86] Old words, new terms and neologisms, circulating stories and eyewitness accounts, and the insights of the odd interviewer all add up to make a bedrock not of experience but of the ideas on which experience can be based. Turning those words and stories into the tools with which a historian reconstructs the past is not a matter of transforming them into something else, but of giving the words and stories the play of contradiction, of leading question, of innuendo and hearsay that they have in practice. Oral historians have not always done this well. In an early, important critique of the use of oral tradition, T. O. Beidelman complained that historians tended to make African culture static to make traditions into historical facts; finding out what really happened obscured how traditions were used on the ground, how they held “social ‘truths’ independent of historical facts.” [87] But the line between different kinds of truth is flexible. Historical facts—like knowledge of segregation and the elite settlers’ club in colonial Nairobi—emerge from social truths, just as social truths develop from readings of historical facts. Hearsay is a kind of fact when people believe it. It is impossible to say that wazimamoto stories, told and retold in East African cities, are independent of historical, or social, or sociological fact. The 1947 riot at the Mombasa fire station is but one example. In October 1958, Nusula Bua was arrested at the Kampala fire station for offering to sell them a man for 1,500/-. He told the fireman he spoke to that he had “about 100 people to sell.” Bua was sentenced to three years, because it was his first offense. According to the magistrate, “People must know that the Fire Brigade is not buying people, but is intended to extinguish fires in burning buildings and vehicles.” [88] It took more than officials’ statements to get people to believe that firemen just put out fires, however. In 1972, the Dar es Salaam section of the Tanzania Standard published a half-page article, “Firemen are not ‘chinja-chinja.’” [89]

Part of what made hearsay so reliable to those who repeated it was that it could resolve some of the confusions that experience actually contained. What happened to people was not always so clear and explicable that they would immediately appreciate its full import, or always have the right words to describe it at the time. Joan Scott’s essay “The Evidence of Experience” (1991) and its critics have noted the limits of the project of social history. The goal of widening the range of experiences that could constitute a national, occupational, or sexual narrative simultaneously reinforced a notion of experience in which individuals are the foundation of evidence, the ultimate authorities on what they lived through. Whatever fractures and fissures in individuals’ senses of themselves and their worlds that shape first-person accounts are lost: instead, Scott argues, “raw events” produce raw analyses, visual and visceral, outside language, and thus beyond the reach of historians who seek diverse experiences in order to relocate subjects in the historical records.[90] Scott’s critics argue that she has gone too far, that even the most counterhegemonic of experiences are described with words borrowed for the purpose: no words are free from the materialism that generates them, and words are often densely packed with historical meanings. Meanings change—like that of benandanti—and terms can lose one historical specificity and take on another. The use and, as chapter 4 argues, misuse, of words carries material histories of work, objects, and places. It is only when these new words are taken up and transformed into personal narratives—when circulating stories are refashioned into personal experiences and the knowledge such experiences contain—that people participate in shaping the language with which they describe the world.[91] When these new words are spoken unproblematically, as hearsay, they offer a contextualization that older terms do not provide. The repetition of hearsay provides a glimpse of the everyday talk and gossip that is a thick description of what otherwise remains as confusing as distinguishing between a wink and a twitch.[92] For example, a woman who thought she was almost captured by wazimamoto could be reassured by hearsay. Mwajuma Alexander was going to her farm late one night in 1959 after an evening’s drinking with her husband and co-wife. Near a neighbor’s farm, she saw a group of men, one of them white, standing around a parked vehicle. One man threw her to the ground. She ran away and hid while they searched for her. Finally, she heard one of them say, “Oh, oh, oh, the time is over,” and they drove off. She fled home. The following day, her husband, on his way to a market in a nearby village, heard that the wazimamoto had caught a woman in the area; this confirmed what everyone suspected.[93] If someone told someone, who told someone, who told Mwajuma’s husband, that wazimamoto were capturing women in the area, then they were.

But what constituted hearsay and circulating stories? Was the common knowledge that wazimamoto had caught a woman here or there made up from bits and pieces of the diverse experiences of many people, or was something else at play, a notion of experience that was not necessarily personal, a notion of experience that incorporated that which was heard about? If historians have worried that experience may be our own rubric for unifying diverse elements into a narrative that subsumes differences, men and women in western Kenya, at least, have suggested that diverse experiences, taken over and told as personal narratives, can reveal the power of difference and the speakers’ knowledge thereof. Such domestication of circulating stories was not boastful exaggeration, or at least it was not only that. Circulating stories were told with convention and constraint. The act of making a wazimamoto story personal—adding names and places and work relations—had nothing to do with making it a better, more detailed story that explained the intricacies of bloodsucking.

The idea that a story may be true although its details are unknown to its tellers is at odds with most of the methodologies used to assess the reliability of testimony or an informant.[94] Vampire stories are neither true nor false, in the sense that they do not have to be proven beyond their being talked about; but as they are told, they contain different empirical elements that carry different weights: stories are told with truths, commentaries, and statements of ignorance. These do not make wazimamoto stories seem unlikely; it is a true story and no one would make a compositional effort to change it to make it more credible. Anyango Mahondo of Siaya, for example, explained that the police were actually the bloodsuckers, something he could neither tell his wife nor his brothers. It was “ordinary people” who could not distinguish between police and firemen. In Kampala

When a man joined the police, he had to undergo the initial training of bloodsucking.…When one qualified there, he was absorbed into the police force as a constable.…At night we did the job of manhunting…from the station, we used to leave in a group of four, with one white man in charge.…Once in town, we would hide the vehicle somewhere that no one could see it. We would leave the vehicle and walk around in pairs. When we saw a person, we would catch him and take him to the vehicle.…Whites are a really bad race.…They used to keep victims in big pits.…blood would be sucked from those people until they were considered useless.…Inside the pits, lights were on whether it was day or night. The victims were fed really good food to make them produce more blood.…The job of the police recruit was to get victims and nothing else. Occasionally, we could go down in the pits, and if we are lucky, we can see the bloodsucking, but nothing else.[95]

This is presumably the account Mahondo could not tell his wife. Chapter 4 argues that this particular chunk of narrative describes on-the-job experience, supervision, promotion, and the place of race and rank therein. Now I want to examine this account as testimony, as a narrative told with different kinds of truths and frank admissions of ignorance. I am not interested in why he told this story, but in how. Mahondo has made hearsay into a narrative of personal experience: the vehicles, the nighttime abductions, the pits, the feeding of victims were all commonplace in the region’s wazimamoto stories. Mahondo does not seem to be talking simply to enhance his dubious prestige;[96] instead, he seems to be establishing truth about wazimamoto—the role of the police, the evils of white people—by telling the story as personal experience and by describing his own role as a participant and a bystander. Indeed, what is important here is the way that Mahondo informs his own storytelling; the process of making a personal narrative was constrained by hearsay: if Mahondo was not speaking the truth, or claiming that he as an eyewitness knew more truth, why did he not make up a better, more elaborate story about what happened in the pits?

It is possible that it was only by conforming to the standards and conventions of hearsay that Mahondo could have been thought credible. Had he stated what actually went on in the alleged secret pits under the Kampala police station, or if he said that he knew what whites did with the blood, he might have revealed himself to be a fraud, rather than a man with insider knowledge. Performance is part of every interview, not the work of specific practitioners in specific places.[97] Speakers use a genre by giving a good example of its use shaped to meet their needs at the moment.[98] Mahondo’s eyewitness account was told the way hearsay wazimamoto stories were told. How the story was performed, and the elements with which it was performed, made it credible. Where it stood on some imaginary line between hearsay and experience had nothing to do with how accurate it was.

Zebede Oyoyo had been captured by Nairobi’s fire brigade in the early 1920s. All his neighbors knew his story, which was how I came to be sent to him early on during my stay in Yimbo in 1986. My research assistant and I interviewed him twice. The first interview was a barely disguised account of his strength—“My fists were like sledgehammers.” “Nobody could come near me.” “When I saw the chance, I dashed out of the room…I outpaced them.” “Those kachinjas really chased me, and when I had completely beaten them, one of them told me, ‘Eh, eh you! You were really very lucky. You will stay in this world and really multiply.” [99] The second interview, ten days later, provided a much more detailed and subtle account of his encounter in a urinal with an African man.

I was caught near River Road. It was near the police station. I had gone for a short call in one of those town toilets. The time was before noon.…When I finished urinating, someone came from nowhere and grabbed my shirt collar. He started asking me funny questions, like “What are you doing here?” I told him I was urinating in a public toilet. On hearing that, the man started beating me. He slapped me several times and pulled me toward a certain room. On reaching that room, I realized that something was wrong. It was then that I started to become wild, and since I was still young…that man could not hold me.…I fought with the man until I got the chance to open the door. I shot out at terrific speed.…When they realized they could not catch me, one of them told me, “You, you are really lucky. You will really give birth to many children and will only die of old age. You were lucky and pray to God for that luck.” [100]

I am not the first to notice that people often revise the answers they have given in a first interview when they are interviewed for a second time. Neither am I the first to find this unremarkable. Historians routinely mediate between different accounts of the same event; why should this mediation be methodologically any different when the different accounts are provided by one person? It is only when a voice is conceived of as a single, spoken rendition of experience that contradictions become extraordinary rather than ordinary. To argue that an informant is mistaken because he or she says different things at different times, or even to argue that one account is wrong, makes linear demands on speech and self: lives and experiences are not such simple, straightforward things that they lend themselves to easy representation; people do not give testimony that fits neatly into chronological or cosmological accounts. Instead, they talk about different things in personal terms; they talk both about what happened to them and about what they did about it, but they also use themselves as a context in which to talk about other things as well.

The idea that a voice, however produced, would not change its mind or its words serves historians, not the speaker’s own complicated interests. What, after all, constitutes the authority of the voice? That historians use what it says? But what happens when voices willingly speak untruths, telling stories the veracity of which they might learn, but that they do not always believe? This raises another question entirely: what makes oral evidence reliable? That it can be made to be verified just like documents, or that it is taken as a kind of evidence produced in circumstances unlike the ones in which people write diaries, reports, and memoranda? What would make oral material true: that truth is spoken during an interview or the repeated social facts and hearsay with which people talk that give us insight into local knowledge beyond one man or woman’s experience? Mwajuma Alexander or Zebede Oyoyo or even Anyango Mahondo were not telling “the truth” but misrepresenting and misconstruing something that happened into vampire stories; they were constructing experience out of widespread hearsay.

Indeed, Oyoyo’s second story seems to have been circulating throughout East Africa in the early 1920s. In 1923, a “Believer” wrote to the Tanganyikan Swahili-language newspaper Mambo Leo saying that he was now convinced that “mumiani are cruel and merciless and kill people to get their blood.” He had seen this himself in Nairobi. Near the new mosque in River Road, there was a long, narrow building and a “government toilet but no permission was given for people to use these toilets. Inside the long narrow house, people stay, wear black clothes and are called Zima Moto, but the thing that is astonishing is that somebody isn’t in this group and they go inside this building, they never come out again.” A Luo man who worked there would not allow his brother to come near the building, not even to greet him.[101] Did Oyoyo bring this story home and craft it to depict his own strength, his own talents, and his own memories?