Part Two

Mind and Body in Practice: Physiology, Literature, Medicine

Four

Thomas Willis and His Circle:

Brain and Mind in Seventeenth-Century Medicine

Robert G. Frank, Jr.

In the autumn of 1663, a middle-aged, and now moderately successful, Oxford physician took up his pen to write an "Amico Lectori Praefatio." He wanted to explain to his prospective readers how he had occupied his two years past, and how he had come to write the more than 450 quarto pages of Cerebri anatome that followed. Academic responsibilities and a disillusionment with his own speculativeness had led him to publication. His position as Sedleian Professor of Natural Philosophy demanded that he lecture twice a week on, as he put it, "the Offices of the Senses, both external and also internal, and of the Faculties and Affections of the Soul, as also of the Organs and various provisions of all these." He had, he said, thought of "some rational Arguments for that purpose, and from the appearances raised some not unlikely Hypotheses, which (as uses to be in these kinds of businesses) at length accrued into a certain System of Art and frame of Doctrine." Yet "when at last the force of Invention [had been] spent," the lecturer reconsidered these things seriously, and "I awaked at length sad, as one out of a pleasant dream." He realized that "I had drawn out for my self and auditors a certain Poetical Philosophy and Physick."[1]

Indeed, if this Clark Library series promises to show us anything, it

[1] Thomas Willis, Cerebri anatome: Cui accessit nervorum descriptio et usus (London, 1664), sig. a1v. This and all subsequent citations to the Cerebri anatome are to the quarto edition of 1664, not to the octavo printing in the same year. Quotations in English are based upon the translation by Samuel Pordage, "Of the anatomy of the brain" [separately paginated], in Thomas Willis, Practice of physick (London, 1681), 53. In all cases the English translation has been checked against the Latin original, since there are occasional discrepancies.

is that problems of "mind and body" have exercised the "force of Invention" of numerous thinkers in the Enlightenment, and that "rational Arguments" derived from "appearances" do most certainly "accrue" into systems of "Doctrine."

Yet our physician, Thomas Willis, felt that there was a way out of this dilemma. The contemplation of the mind and its faculties need not lead invariably to "Poetical Philosophy." He felt that he himself had entered upon a "new course," independent both of the "Received opinions of others," and of the "guesses" of his own mind. He would believe only "Nature and ocular demonstrations."

Therefore thenceforward I betook my self wholly to the study of Anatomy: and as I did chiefly inquire into the offices and uses of the Brain and its nervous Appendix, I addicted my self to the opening of Heads especially, and of every kind, and to inspect as much as I was able frequently and seriously the Contents; that after the figures, sites, processes of the whole and singular parts should be considered with their other bodies, respects, and habits, some truth might at length be drawn forth concerning the exercise, defects, and irregularities of the Animal Government; and so a firm and stable Basis might be laid, on which not only a more certain Physiologie than I had gained in the Schools, but what I had long thought upon, the Pathologie of the Brain and nervous stock, might be built.[2]

This was a bold enterprise indeed: to believe that systematic anatomy of the brain, especially of the comparative sort, would lead to discovering patterns of function and dysfunction, and that these in turn would illuminate the cluster of subjects that launched Willis in the first place—the nature of senses and the faculties of the soul.

Yet it turned out to be an enterprise that, in the eyes of Willis's contemporaries and successors, was both highly productive and very successful. Cerebri anatome (1664) was just the first of Willis's books on the nervous system and its attributes. Following soon thereafter was the Pathologiae cerebri (1667),[3] then a defense of his views on the neural origins of hysteria and hypochondria (1670),[4] and De anima brutorum

[2] Willis, Cerebri anatome, sig. a2r; "Anatomy of the brain," 53.

[3] Thomas Willis, Pathologiae cerebri, et nervosi generis specimen: In quo agitur de morbis convulsis, et de scorbuto (Oxford, 1667); translation by Pordage as "An essay of the pathology of the brain and nervous Stock: In which convulsive diseases are treated of," in Willis, Practice of physick [separately paginated].

[4] Thomas Willis, Affectionum quae dicuntur hystericae & hypochondriacae pathologia spas-modica vindicata, contra responsionem epistolarem Nathanael Highmore, M.D.: Cui accesserunt exercitationes medico-physicae duae. 1. De sanguinis accensione. 2. De motu musculari, (London, 1670). The response to Highmore has not been translated; the other two tracts appear as "Of the accension of the blood" and "Of musculary motion" in Willis, Practice of physick [separately paginated].

(1672).[5] These more than 1,400 quarto pages all arose explicitly out of his work at Oxford. The neurological works were embedded in, and made up the largest part of, an oeuvre that occupied an honored place in late-seventeenth- and eighteenth-century medicine. Willis's individual treatises went through numerous editions in his own lifetime. His works were rapidly translated into English in the 1680s, and his Opera omnia went through eleven editions between 1676 and 1720.[6] They continued to be highly influential through the 1770s, and in the 1820s the neuro-anatomist Karl Friedrich Burdach had many good things to say about Willis's work on the brain.[7] In the twentieth century, even after his investigations have ceased to have an active scientific influence, Willis is still widely known among neuroscientists, and he attracts a steady stream of biographers and commentators.[8] Certainly then, in any discussion of "mind and body" in the Enlightenment, Willis should command our attention.

Here I wish to examine, not effects, but origins. How is a highly im-

[5] Thomas Willis, De anima brutorum quae hominis vitalis ac sensitiva est, exercitationes duae. Prior physiologica ejusdem naturam, partes, potentes & affectiones tradit. Altera pathologica morbos qui ipsam, & sedem ejus primarium, nempe cerebrum & nervosum genus afficiunt, explicat, eorumque therapeias instituit (Oxford, 1672); the Pordage translation is Thomas Willis, Two discourses concerning the soul of brutes, which is that of the vital and sensitive of man. The first is physiological, shewing the nature, parts, powers, and affections of the same. The other is pathological, which unfolds the diseases which affect it and its primary seat; To wit, the brain and nervous stock, and treats of the cures (London, 1683).

[6] Consider for a moment the numbers and distribution of Willis's individual writings: Diatribae duae, fifteen editions in the period 1659-1687, published at London, Amsterdam, Geneva, Paris, The Hague, and Middelburgh; Cerebri anatome, eight editions in 1664-1683, published at London, Amsterdam, and Geneva; Pathologiae cerebri, eight editions in 1667-1684, published at Oxford, London, Amsterdam, and Geneva; Affectionum, four editions in 1670-1678, published at London, Leiden, and Geneva; De anima brutorum, eight editions in 1672-1683, published at Oxford, London, Amsterdam, Lyon, and Cologne; Pharmaceutice rationalis, parts I and II, eleven editions in 1674-1680, published at Oxford, London, Amsterdam, The Hague, Lyon, Geneva, and Cologne. After Willis's death the most common way of bringing out his writings was as an Opera omnia or an edition abridged from it, either in Latin or in English; between 1676 and 1720 there were sixteen such editions, published at London, Geneva, Lyon, Amsterdam, Cologne, and Venice.

[7] Cf. the praise for Willis in Antoine Portal, Histoire de l'anatomie et de la chirurgie (Paris, 1770-1773), 3:86-105, and A. Meyer, "Karl Friedrich Burdach on Thomas Willis," Journal of the Neurological Sciences 3 (1966): 109-116.

[8] Since the 1920s, articles on Willis have appeared at the rate of about four to eight per decade; the exception is the 1960s, in which thirty-three articles and books on Willis were published, many of them prompted by the tricentennial of Cerebri anatome.

portant set of results and ideas created? Specifically, how does one work on the problem of brain and mind in the context of seventeenth-century medicine and culture? I use the phrase "work on" quite deliberately, because my primary focus is the process of creation, not the results.

I would like to explore this creative process by asking three interrelated sets of how questions. How biographically? What is the trajectory of a man's life that brings him to a point of creativity, and what is the constitution and integration of the elements of that life such that he creates a product in a unique way? How operationally? What are the social and scientific circumstances under which the work is carried out, and how do these circumstances relate to the essential nature of the product? How intellectually? In what ways does a scientist approach his subject, and deal with it, so as to produce new ideas and results? Since the object of Willis's inquiry was the brain and nervous system, neuro-anatomy necessarily enters into the discussion; but its entry is subservient to my larger aim of showing Willis and his circle at work. I am not concerned here with a complete description of Willis's neuroanatomy and neurophysiology. Nor do I wish to judge in what ways his work anticipates, or fails to anticipate, the concepts of the twentieth-century neurosciences. I ask, rather, how one constructs a system of brain and mind, three hundred years ago, in the absence of what we flatter ourselves by calling the necessary tools and insights of modern science.

WILLIS'S PATH TO THE BRAIN

Willis is in many ways very apt for such purposes of exemplification. He was no great genius. Rather, he was an ordinary man in extraordinary times. He lived through a revolution and a reaction. His life straddled the transition between late-Renaissance and early-Enlightenment England, and he lived it successfully in two contrasting spheres of academic reclusion and worldly bustle.

Willis was born in 1621 near Oxford, and stayed in the shadow of its spires for almost half a century, moving to London only in 1667, where he died in 1675.[9] In his early life he was surrounded by the traditional

[9] To date, the only full-length biography is Hansruedi Isler, Thomas Willis: Ein Wegbereiter der modernen Medizin, 1621-1675 (Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, 1965); this was translated, with additions, by Islet, Thomas Willis, 1621-1675: Doctor and Scientist (New York: Hafner, 1968). The late Kenneth Dewhurst has been the scholar most active in writing about Willis over the past two decades. Much biographical material is contained in the long introductions to his editions of Willis manuscript material: Thomas Willis's Oxford Lectures (Oxford: Sandford, 1980), 1-49; Willis's Oxford Casebook (1650-52) (Oxford: Sandford, 1981), 1-59. A useful synoptic view of Willis's life and scientfic ideas is Robert G. Frank, Jr., "Thomas Willis," in Dictionary of Scientific Biography (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1970-), 14: 404-409.

verities of crown and church; then, when King confronted Parliament, the world was, in Christopher Hill's phrase, turned upside down. Like many, he fought for the Royalist cause between 1643 and 1646, main-rained a secret opposition through the Commonwealth period, and was elated at the Restoration. Nor did Willis possess unusual qualities of personal magnetism. He was merely honest in speech and conservative in mentality. With typical earthiness, John Aubrey tells us that Willis was of "middle stature: darke red haire (like a red pig)," and "stammered much."[10] Antony Wood called him simply "a plain man, a man of no carriage, little discourse, complaisance, or society."[11] What was there about his life that brought him to the enterprise of grounding mental phenomena in neural tissue? His biography, which has been reasonably well explored, contains scattered bits of evidence that bear upon the origins of his neurological work.

Willis was first and last a clinician. He began practicing medicine at Oxford about age 24, and continued his profession daily until the week of his early death at age 54. The greater part of his first book in 1659 applied ideas of fermentation to explain fevers,[12] and his last, the Pharmaceutice rationalis of 1674, was an omnium-gatherum of his clinical judgments and prescriptions.[13] He was a successful practitioner, but this came only slowly. As a young doctor in the late 1640s he hustled for pa-

[10] "Brief Lives," Chiefly of Contemporaries, Set Down by John Aubrey, between the Years 1669 & 1696, ed. Andrew Clark (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1898), 2: 303.

[11] Anthony Wood, Athenae Oxonienses: An Exact History of All the Writers and Bishops Who Have Had Their Education in the University of Oxford, new ed., ed. Philip Bliss (London: Rivington, 1813-1820), vol. 3, col. 1051.

[12] Thomas Willis, Diatribae duae medico-philosophicae, quarum prior agit de fermentatione sive de motu intestino particularum in quovis corpore; altera de febribus, sive de motu earundum in sanguine animalium. His ascessit dissertatio epistolica de urinis (London, 1659). The three treatises are paginated separately, so I shall refer to them as De fermentatione, De febribus, and De urinis. All were translated by Pordage as "Of fermentation," "Of feavers," and "Of urines" [separately paginated], in Willis, Practice of physick. In this, as in other works of Willis for which more than one edition was published in Willis's lifetime, one must exercise caution in using the Pordage translation; it sometimes contains intercalated sentences, paragraphs, or even sections that are not found in the first edition.

[13] Thomas Willis, Pharmaceutice rationalis. Sive diatriba de medicamentorum operationibus in humano corpore [Pars I] (Oxford, 1674); translation by Pordage as "Pharmaceutice rationalis, Part I," in Willis, Practice of physick. Thomas Willis, Pharmaceutice rationalis... Pars secunda (Oxford, 1675); translation by Pordage as "Pharmaceutice rationalis, Part II," in Willis, Practice of physick.

tients on market days in neighboring towns, and a clinical notebook kept in 1650 shows a practice that was certainly not booming.[14] But by 1657 he had acquired enough skill, patients, and financial security to marry, and the Restoration set his career firmly on the upward path. By the early 1660s he was buying properties in Oxford, and just before his departure from there he had the highest income in the town.[15] The move to London brought more success and, as Wood noted, "in very short time after he became so noted, and so infinitely resorted to, for his practice, that never any physician before went beyond him, or got more money yearly than he."[16]

But Willis was successful in more than simply monetary terms. He was a remarkable clinical observer. His characterizations of epidemics were particularly acute; he reported in detail the first English outbreak of war typhus among the Oxford troops in 1643, cases of plague in 1645, measles and smallpox in 1649 and 1654, and influenza in 1657. He also recorded what seems to be the first reliable clinical description of typhoid fever. For a variety of other clinical descriptions, his works contain in each case the locus classicus: myasthenia gravis; the distinction between acute tuberculosis and the chronic fibroid type; the first clinical and pathological description of emphysema; extrasystoles of the heart; aortic stenosis; heart failure in chronic bronchitis; emboli lodged in the pulmonary artery; the first European to note the sweet taste of the urine in diabetes mellitus.[17] Overall, he was a moderate in therapy[18] and seems—at least as reflected by his writings—to have had no great knowledge of Galen or Hippocrates. Throughout his life, his abiding interest was his patients, not learned medicine.

In addition to being an acute but conservative physician, he was also

[14] Aubrey, "Brief Lives " 2: 303. Cf. Dewhurst, Willis's Oxford Casebook, where Willis notes seeing only forty-six separate patients in 1650; many, however, were seen more than once, and it seems most likely that Willis did not record all of his cases.

[15] On Willis's growing wealth and acquisition of properties, see Dewhurst, Willis's Oxford Lectures, 9-12, 14-18, 20-26; Willis's Oxford Casebook, 41-42, 55-56.

[16] Wood, Athenae, vol. 3, col. 1051.

[17] See, for example, the selections from Willis's writings in Ralph H. Major, Classic Descriptions of Disease (Springfield, Ill.: Charles C. Thomas, 1932), 121-124, 133-136, 192-194, 534-536, 541-545, 591-593. A good overview of Willis's clinical accomplishments is R. Hierons, "Willis's Contributions to Clinical Medicine and Neurology," Journal of the Neurological Sciences 4 (1967); 1-13.

[18] Willis's practice, as it appeared to his contemporaries, is reflected in the diary-like commonplace books of his younger Oxford contemporary, John Ward; see Robert G. Frank, Jr., "The John Ward Diaries: Mirror of Seventeenth-Century Science and Medicine," Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 29 (1974): 147-179.

a staunch churchman. He seems originally to have been destined for holy orders, but the Civil War derailed his clerical career. He maintained his strong Anglicanism throughout the interregnum, and his residences at Oxford, both when he lived in Christ Church and in Beam Hall, were used regularly for sub-rosa worship. His friends during this period included John Fell (whose sister he married), Gilbert Sheldon, John Dolben, and Richard Allestree; after the Restoration these four became, respectively, the Bishop of Oxford, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Archbishop of York, and the Regius Professor of Divinity as well as the Provost of Eton.[19] Willis was especially close to Fell and Allestree; not only did Richard Allestree take a course in chemistry from Willis, but his brother James, the printer, brought out Willis's first four books.[20]

Willis's religion, although not at all theological, was more than merely a matter of friends and politics. He gave to the poor all the fees he earned on Sundays. He went to church daily, and when he found that his London practice precluded midday worship, he paid a priest at St. Martin's in the Fields to read prayers early and late, for such as he, who could not otherwise attend. Characteristically, he endowed this position in his will. As Wood said, he "left behind him the character of an orthodox, pious, and charitable physician."[21]

This orthodoxy squared with his early philosophical education. He had matriculated at Oxford in the boom years of the mid-1630s, proceeding to the B.A. in 1639, and to the M.A. in 1642.[22] At that time the colleges were throwing up new buildings with abandon to accommodate the thousands who, largely for social reasons, wanted a traditional uni-

[19] Wood, Athenae, vol. 3, cols. 1049—1050; Anthony Wood, The History and Antiquities of the University of Oxford, ed. and trans. John Gutch (Oxford: For the editor, 1796), 2: 613; Cf. the brief obituary by John Fell which was appended to the Pharmaceutice rationalis... Pars secunda, sig. b3v-b4r; "Pharmaceutice rationalis, Part II," sig. A2v-A3r.

[20] Richard Allestree was reputed to be the author of The causes of the decay of Christian piety (London, 1668), and on the copy in the Bodleian Library is the anonymous note that "Dr. Allestree was author of this book, and wrote it in the very same year wherein he went thro' a course of chymistry with Dr. Willis, which is the reason why so many physical and chymical allusions are to be found in it": Dictionary of National Biography 15: 87, under entry "Pakington". Other than purely conventional figures of speech, there are medical or chemical references in Causes at pp. 4-5, 29, 58, 75, 118-119, 122, 253. James Allestry, Richard's brother, published Willis's Diatribae duae (1659), Cerebri anatome (1664), Pathologiae cerebri (1667), and Affectionum (1670).

[21] Wood, Athenae, vol. 3, col. 1053.

[22] Joseph Foster, ed., Alumni Oxonienses: The Members of the University of Oxford, 1500 -1714 (Oxford: Parker, 1891-1892), 4: 1650. Willis matriculated from Christ Church, 3 March 1636/7; B.A., 19 June 1639; M. A., 18 June 1642.

versity education.[23] The curriculum was still highly Scholastic, and was organized around the two medieval elements of lectures and disputations.[24] Especially in the years between the B.A. and the M.A., Willis would have studied traditional natural philosophy, geometry, and astronomy. He would have dutifully read his Aristotle, absorbing what he was later to call "those vain figments," the Peripatetic forms and qualities.[25] Although Willis is often—and rightly—portrayed as one of the new breed of savant that the seventeenth century created, he was certainly perceived by his contemporaries as intellectually reliable enough that, in 1660, through the influence of Sheldon, he was elected Sedleian Professor at £120 per annum.[26]

Physician, pillar of the church, Scholastic—described thus far, Willis would hardly seem an innovator. How did he come to his reputation as a master of brain anatomy and theoretician of the soul? His portal of entry, I would argue, was originally not anatomy, as one would expect, but a subject more appropriate to the humble prescribing medico: chemistry. As early as 1648, when he still lived in bachelor rooms in Christ Church, he joined with another Anglican perforce turned physi-

[23] On the growing popularity of the English universities see Mark H. Curtis, Oxford and Cambridge in Transition, 1558-1642 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1959); Kenneth Charlton, Education in Renaissance England (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1965); Hugh Kearney, Scholars and Gentlemen: Universities and Society in Preindustrial Britain, 1500-1700 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1970); Lawrence Stone, ed., The University in Society (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974). In the 1540s Oxford admitted about 40 B.A.s and 20 M.A.s each year; by the 1620s this had grown to the extent that about 400 new students came to Oxford each year, of whom an average of 240 would proceed to the B.A., and about 150 to the M.A.; see Robert G. Frank, Jr., "Science, Medicine and the Universities of Early Modern England: Background and Sources," History of Science 11 (1973): 194-216, 239-269, especially 213. For the physical growth of the colleges in the pre-Civil War period, see the Victoria History of the County of Oxford, ed. H. E. Salter and M. D. Lobel (London: Institute of Historical Research, 1954), 3:96, 102, 115-116, 127-128, 169-170, 216-217, 240-242, 272-274, 283-285, 289.

[24] The relation between statutory forms and scholastic content at an English university is brilliantly set forth in William T. Costello, The Scholastic Curriculum at Early Seventeenth-Century Cambridge (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1958). On the relation of science to the scholastic format, see Frank, "Science, Medicine and the Universities," 200-207.

[25] For a description of the arts curriculum at Oxford in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, see Andrew Clark, Register of the University of Oxford, vol. 2 (1571-1622), part 1 (Oxford: Oxford Historical Society, 1887).

[26] The documents on Willis's election are in the Oxford University Archives, "Regis-trum Convocationis, 1659-1671," reverse codex f. 4r-v.

cian, Ralph Bathurst, in preparing chemical compounds.[27] His case notes of 1650, although largely Galenic in framework, show him edging toward chemical explanations of blood composition. Take, for example, the phenomenon of diffused pains; Willis thought they were due to an "acrid salt."[28] By 1652 Willis was one of an inner circle of eight Oxford virtuosi who, according to Seth Ward, had "joyned together for the furnishing an elaboratory and for makeing chymicall experiments wch we doe constantly every one of us in course undertakeing by weeks to manage the worke."[29] Willis's neat accounts of money "laid out at Wadham coll" for chemical apparatus and supplies, written in the back of one of his surviving casebooks, no doubt dates from his rota of managing "the worke." It was no mean operation; the expenses up to that point totaled almost twenty-five pounds, at a time when a college fellow was paid three pounds a years to tutor a young gentleman in Oxford.[30] As Willis came to know other virtuosi, such as John Wilkins and Robert Boyle, his reputation as a chemist spead.[31] The London projector Samuel Hartlib recorded in November 1654 that

Dr. Wellis [sic] of Dr. Wilkins acquaintance a very experimenting ingenious gentleman communicating every weeke some experiment or other to Mr. Boyles chymical servant, who is a kind of cozen to him. He is a great Verulamian philosopher, from him all may bee had by meanes of Mr. Boyle.[32]

[27] See the letters of John Lydall from Oxford in 1649 referring to "Mr. Willis our Chymist," extracted and explicated in Robert G. Frank, Jr., "John Aubrey, F.R.S., John Lydall, and Science at Commonwealth Oxford," Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 27 (1973): 193-217, especially 196-198, 213.

[28] Dewhurst, Willis's Oxford Casebook, 109; other references of a chemical bent are on pp. 82, 83, 98, 110, and 119.

[29] Seth Ward to Sir Justinian Isham, 27 February 1652, in H. W. Robinson, "An Unpublished Letter of Dr. Seth Ward Relating to the Early Meetings of the Oxford Philosophical Society," Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 7 (1949): 68-70.

[30] Dewhurst, Willis's Oxford Casebook, 153-154.

[31] Wilkins was installed as Warden of Wadham in April 1648 (Wood, History and Antiquities 2: 570), although given their difference in politics, they may not have gotten to know each other until their common experience in William Petty's club about 1650. Cf. Robert Boyle to Ralph Bathurst, 14 April 1656, where he sends his service "to Dr. Willis, Dr. Ward, and the rest of those excellent acquaintances of yours, that have been pleased to tolerate me in their company" (Thomas Warton, The life and literary remains of Ralph Bathurst, M.D. [London, 1761]. pp. 162-164).

[32] Samuel Hartlib, "Ephemerides" [diary-like commonplace books], 1654, ff. WW-WW 7-8, Harlib Papers, Sheffield University Library. The Hartlib Papers are quoted by the kind permission of their owner, Lord Delamere.

By June 1656 Willis had completed his first chemical work, "De fermentatione"; he circulated it among his fellow scientists in Oxford, and word of it even reached London.[33] In late 1658 he appended to it some additional tracts on fevers and on urines, and published the whole as Diatribae duae medico-philosophicae (1659).[34] The book attracted much attention not only in Willis's coterie but in London and abroad.[35] To his local reputation as an adept, Willis thereby added an international one as a theoretician of the spagyric art.

Since Willis's ideas about the animal and human body were built upon his chemistry, one must understand something about it in order to see how he approached problems of brain function. All bodies, he believed, were composed of five "principles": spirit, sulphur, salt, water, and earth. The last two were traditional Aristotelian "elements," while the first three were modifications of Paracelsian "principles"—in his chemistry, as in most other things, Willis was always the compromiser between ancients and moderns.

But unlike Aristotelians and Paracelsians, Willis did not believe that the five principles were names for homogeneous substances; rather, they were labels for categories of particles. All spirit particles, for example, shared the property of being highly subtle and active. They were always

[33] Hartlib, "Ephemerides," 1656, f. 48-48-3, where Hartlib noted that Willis was "a leading and prime man in the Philosophical Club at Oxford," who "hath written a treatise De Fermentatione," which John Aubrey commended highly. Robert Wood, who was at Oxford from 1640 to 1656, and a year younger than Willis, wrote to Hartlib: "If the Booke you write of de Fermentatione be Mr Willis his of Oxford, I am confident it is an excellent peece, having formerly seen some sheets of his upon ye subject, when we met at a Club, at Oxford" (Wood to Hartlib, 9 February 1658[/9], Hartlib Papers, Bundle XXXIII (1)).

[34] Cf. A Transcript of the Registers of the Worshipful Company of Stationers, from 1640-1708 (London: Privately printed, 1913-1914), 2: 207, where the Diatribae duae was licenced on 26 November 1658.

[35] On 16 December 1658, Hartlib thanked Boyle for sending a copy of Willis's Dia-tribae duae from Oxford, and noted of the London chemist Frederick Clodius that his "chemical son's head and hands are much taken up with animadversiones on Dr. Willis's book, he having very clear reason and experiences to dislike very many particulars in it: but, no doubt, of this he will write himself" (Hartlib to Boyle, in The works of the Honourable Robert Boyle, ed. Thomas Birch, 2d ed. [London, 1772], 6: 115-116). Three months later Robert Wood wrote from Dublin: "A frend from Oxford has sent me Mr. Willis his much approved Booke de Fermentatione, so yt though I shall not now need yours... yet I shall still value your intentions as highly as I do the booke it selfe" (Wood to Hartlib, 2 March 1658[/9], Hartlib Papers, Bundle XXXIII (1)). Boyle also passed on a copy to John Beale in Herefordshire: cf. Samuel Hartlib to John Worthington, 26 June 1659, The Diary and Correspondence of Dr. John Worthington, ed. James Crossley (Manchester: Chetham Society. 1847), 1: 135.

attempting to fly out of an object, and had to be bound to other, heavier particles. But because not all spirit particles were of identical size and activity, they could not all fly away at the same time. "Spirit," for Willis, described a population of particles with common characteristics and activities, but which, like individuals that made up a species, were not necessarily identical.

The other four elements were conceived in a similar manner. Sulphureous particles were rather less active than spirit, but they too were capable of flying away. Less subtle than spirit, they were more vehement and unruly. With a little motion, they produced maturation and sweetness; with more motion, heat; with the maximum motion, the body dissolved into flames. Salt was of a more fixed nature than the previous two; it bestowed solidity on things, and retarded their dissolution. The two last principles served as passive matrices for the active ones. If particles of earth predominated, then the substance was solid; if those of water, it was liquid. Willis could, then, look at a biological substance like blood, or a part of the brain, and conceive of it as a heterogeneous population of particles, of varying types, and varying motions. Particles of different principles could combine with each to produce "copula"—spirito-sulphureous, salino-sulphureous, and so forth—which combined the chemical properties of their constituent parts.[36]

Note, though, what Willis had done. He had created a corpuscular matter-theory, and its correlate chemistry, in a way that differed from classical atomism, which did not allow matter to have properties in and of itself. His youth, the 1630s and 1640s, had been a time of revival, and reworking, of Epicurean corpuscular theories.[37] René Descartes had made particles of matter in motion the basis of his supremely influential Principia philosophiae (1644)[38] Although Descartes's mechanistic explanations applied to animal bodies appeared only in his posthumous De l'homme (1664), many of his physiological ideas were expounded earlier by his Dutch disciples, Henrik de Roy (Henricus Regius) in his Fundamenta physices (1646) and Fundamenta medica (1647), and Cornelis

[36] Willis, De fermentatione, 1-17; "Of Fermentations," 1-8. The Pordage translation includes material added in later editions.

[37] On the problems and sources of early modern atomism and the corpuscular philosophy, see Kurd Lasswitz, Geschichte der Atomistik vom Mittelalter bis Newton (Hamburg: Leopold Voss, 1890); Marie Boas, "The Establishment of the Mechanical Philosophy," Osiris 10 (1952): 412-541; Robert Hugh Kargon, Atomism in England from Harlot to Newton (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1966).

[38] René Descartes, Discours de la méthode (Leiden, 1637); Principia philosophiae (Amsterdam, 1644); De l'homme (Paris, 1664).

Hooghelande in his Cogitationes (1646).[39] Marin Mersenne's brand of mechanism was most clearly delineated in the Cogitata physico-mathematica (1644).[40] Pierre Gassendi's massive three-volume Animadversiones in decimum librum Diogenis Laertii (1649) established him as the leading spokesman for, and interpreter of, Epicurean atomism as applied to science.[41] Gassendi's was the most highly ramified of the corpuscularian philosophies. According to him, there was only matter and the void. Matter was of one type, and it was only the varying size and figure of the atoms, and their concretion into second-order particles called moleculae, that constituted perceived differences in matter.[42] In page after doublecolumned page, Gassendi went on to show how light, color, sound, odors, rarity, density, perspicuity, opacity, subtility, hardness, smoothness, fluidity, humidity, and ductility—all could be transposed out of the Aristotelian categories of essences and substantial forms, into the matter-and-motion categories of the atomistic conceptual scheme.[43]

Willis was familiar with much of this literature, and explicitly cites Descartes, Regius, Hooghelande, Mersenne, and Gassendi. Yet he preferred a corpuscularian chemistry in which particles, although of possibly differing activities, had inherent properties by which they could act. In this version, he said, chemistry could demonstrate the principles of natural philosophy, whereas the "Epicurean hypothesis" only supposes them.[44]

However, Willis did not come by his corpuscularianism merely in the library. It was nonexistent in his casebook of 1650, well established in the De fermentatione of 1656, and grew into efflorescence in his works written in the 1660s. Whence came such an intellectual trajectory? I

[39] Henrik de Roy, Fundamenta physices (Amsterdam, 1646) and Fundamenta medica (Utrecht, 1647); Cornelis Hooghelande, Cogitationes, quibus Dei existentia et animae spiritualitas, et possibilis cum corpore unio, demonstrantur; necnon brevis historia oeconomiae corporis animalis proponitur, atque mechanice explicatur (Amsterdam, 1646).

[40] Marin Mersenne, Cogitata physico-mathematica in quibus tam naturae quam artis effectus admirandi certissimis demonstrationibus explicantur (Paris, 1644). On Mersenne see the excellent study by Robert Lenoble, Mersenne; ou, La naissance du mécanisme (Paris: Vrin, 1943).

[41] Pierre Gassendi, Animadversiones in decimum librum Diogenis Laertii (Lyon, 1649); on Gassendi's atomism see Bernard Rochot, Les travaux de Gassendi sur Epicure et sur l'atomisme, 1619-1658 (Paris: Vrin, 1944), and Lasswitz, Geschichte der Atomistik 2: 126-188.

[42] Gassendi, Animadversiones 1: 222-236.

[43] Ibid., 236-362.

[44] Willis, De fermentatione, 4; "On fermentation," 2. The English translation includes a remark that if anyone were to say that the chemical and atomical schemes can be brought together, he would not disagree; but he will leave it to those more clever than he to devise or dream philosophy.

would argue that it was rooted in Willis's experiences in informal scientific groups that met at Oxford in the 1650s and 1660s. Among the participants in these groups were men like William Petty, Robert Boyle, and John Wallis, all of whom we know were, from their Continental contacts and reading, particularly interested in Gassendian atomism.[45] Willis worked with men like these by being a member of no fewer than five such groups that met over the period from about 1648 to 1667.[46] The first was a small chemistry group with Ralph Bathurst and John Lydall that worked at Trinity and Christ Church about 1648-1649.[47] The second was organized by William Petty from late 1649 to early 1652, at his lodgings over an apothecary shop in the High Street. The third convened, from the early 1650s to about 1657, at Wadham College under the auspices of John Wilkins, its Warden. It was by far the largest and most well-organized of the groups, and provided part of the nucleus for the founding of the Royal Society in London in 1660. The fourth group met rather more sporadically at Robert Boyle's lodgings in the High Street, from late 1657 to late 1659, and from July 1664 to April 1668. And the last was Willis's own, largely of physicians and chemists, that met at Beam Hall, in Merton Street, from the late 1650s up to Willis's departure to London in 1667.[48]

Through each of these groups in which Willis participated there were continuities and discontinuities of membership. Younger men became interested in scientific topics, and were brought into activities, while

[45] For evidence of the popularity of the French and Dutch mechanists among Oxford scientists, see Robert G. Frank, Jr., Harvey and the Oxford Physiologists: Scientific Ideas and Social Interaction (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1980), 92-93·

[46] For a survey of Oxford scientific groups in the 1650s and 1660s, see ibid., 43-89; also Charles Webster, The Great Instauration: Science, Medicine and Reform, 1626-1660 (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1976), 153-178.

[47] Frank, "John Aubrey," 196-198.

[48] On the venues, membership, and activities of the Petty, Wilkins, and Boyle clubs, see Frank, Harvey and the Oxford Physiologists, 52-57, and the sources cited in the notes on pp. 312-314. Willis's membership in these groups is recorded in the following sources: Bodleian Library, MS. donat. Wood 1, pp. 1-3; John Wallis, A defence of the Royal Society (London, 1678), 8; John Wallis's autobiography (1697) in Peter Langtoft's chronicle, ed. Thomas Hearne (Oxford, 1725), 1: clxiii-clxiv; Wood, History and Antiquities 2: 633; Thomas Sprat, The history of the Royal-Society of London, for the improving of natural knowledge (London, 1667), 52-58; Aubrey, "Brief Lives " 2: 141; participant in the "resurrection" of Anne Green, see [Richard Watkins], Newes from the dead, 2d ed. (Oxford, 1651, 1-8; Walter Pope, The life of the fight reverend father in God Seth, Lord Bishop of Salisbury (London, 1697), 29.

others moved away from Oxford or lost interest. Most of all, these shifting constellations gave rise to numerous cooperative research projects. The ethos was one not of discussion and debate but of experimentation, trial, and manual exploration. Again and again, clusters of investigators served as helpmates, audience, and witnesses in one another's scientific work.

This then was the constellation of elements in Willis's life at the time of the Restoration, the six kinds of conceptual and social raw material out of which one shaped an approach to the relation of brain and soul. They reflected the many sides of the newly elected professor of natural philosophy: Willis the clinician of increasing acuity and fame; Willis the staunch Royalist and devout Anglican; Willis the man of traditional philosophical education, recently placed into an endowed professorship; Willis the enthusiastic experimental chemist; Willis the afficionado of corpuscular philosophies; and Willis the ever-active member of Oxford scientific circles.

ORIGINS OF A NEUROLOGICAL RESEARCH PROGRAM

Yet even given all of this, in 1660 there was no inevitability to Willis's future interest in the brain; it arose as a fortuitous concourse—a phrase beloved by the atomists—of incitement and opportunity.

As he himself noted in his "Praefatio," the incitement was his new responsibilities as a teacher. What were those duties? The Laudian statutes, adopted in the 1630s but codifying the practices of previous decades, specified them quite clearly. During the Michaelmas, Hilary, and Easter terms, each about eight weeks in length, Willis was to read to the bachelors of arts at 8:00 A.M. on Wednesdays and Saturdays. For failing to read a lecture, the professor incurred a fine of ten shillings (about $200 proportionally today), whereas the B.A.s were to be fined four-pence (perhaps $6) for failure to attend. His lectures were to be drawn from a list of Aristotle's works: De physica, De caelo, Meteorologica, De generatione et corruptione, De anima, and the Parva naturalia.[49] The first four fall into the category of the physical sciences, while the last two might properly be called psychology. It was not a modest province of knowledge; Willis's teaching obligations covered two of the eight cate-

[49] John Griffith, ed., Statutes of the University of Oxford Codified in the Year 1636 under the Authority of Archbishop Laud, Chancellor of the University (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1888), 36-37.

gories into which Aristotle's total surviving works could be distributed.

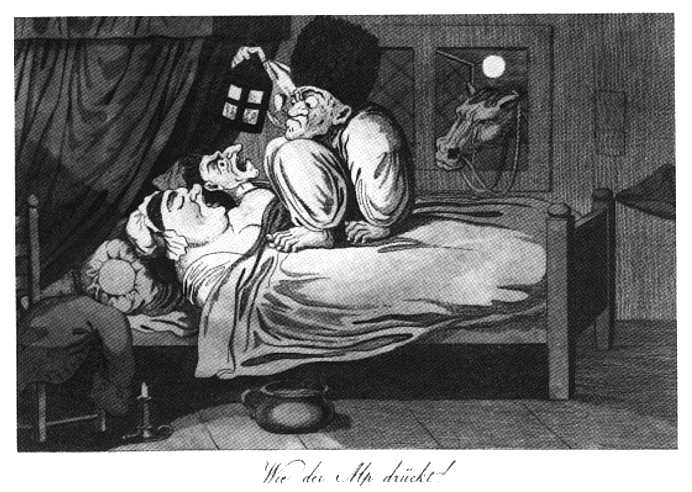

Such were the statutory injunctions. But in good English fashion, at Oxford the statutes were venerated more in the breach than the observance. By the 1650s the Savilian Professors of Astronomy and Geometry—Willis's fellow club members John Wallis and Seth Ward—were teaching the ideas of Copernicus and Kepler, defending the "Atomicall and Magneticall" hypotheses, and in general feeling free, as Ward and John Wilkins put it, to "discent" from Aristotle, "and to declare against him."[50] Willis did no less. He was naturally drawn more to the psychological side of his bailiwick than to the physical, so he chose to honor the statutes by lecturing within the general subject area with which De anima and the Parva naturalia dealt: the principles animating vegetable and animal life, the senses and sensation, memory, sleep and dreams. That he exercised his freedom from the very beginning can be seen in a passing reference in a commonplace book of a medical student; John Ward, of Christ Church, noted in February 1661 that "Dr. Willis is now reading about ye succus nervosus," and that the professor doubted that the nerve juice actually exercised its reputed nutritive function.[51] Willis's lectures went on to include the nature of life, sensation, movement, narcotics, nutrition, convulsions, epilepsy, hysteria, sleep and wakefulness, nightmare, coma, vertigo, paralysis, delirium, phrensy, melancholia, mania, stupidity, the cerebrum, the cerebellum, and nerve fibers. In fact, it seems that wherever Willis encountered an interesting observation or result, it might well end up as part of his teaching; in 1664 his protégé, Richard Lower, observed an interesting anatomical arrangement in the stomach of a ruminant, and Willis was, as Lower reported to Boyle, "so taken with it" that he wanted to "make a lecture of it the next term."[52] Such freedom within statutory constraints allowed Willis to shape his teaching to reflect his own interests, which were largely chemical and medical. Exactly the opposite happened once he left Oxford, and paid a deputy to discharge his obligations as Sedleian Professor; in 1669 George Hooper was overseeing disputations on such subjects in the physical sciences as "Whether the Medicean stars are

[50] [Seth Ward], Vindiciae academiarum (Oxford, 1654), 2, 28-30, 32, 45-46; quotation from p. 2, which was written by John Wilkins.

[51] John Ward, diary-like commonplace books, 16 vols., in the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, D.G. MSS. V.a. 284-299; hereafter cited as Ward, "Diary." Quotation is from Ward, "Diary," VIII, f. 39v. See also Frank, "The John Ward Diaries," 153-154.

[52] Richard Lower to Robert Boyle, 24 June 1664, in The works of the Honourable Robert Boyle, ed. Thomas Birch, 2d ed. (London, 1772), 6: 474.

the moons of Jupiter? Affirmative," and "Whether a vacuum can exist? Negative."[53]

We know Willis took such a biological approach and covered such neurological subjects, because abstracts of some of his lectures have survived in the form of student notes—notes that are of particular interest and significance both for their content and for their auditors. Most probably in the late 1661 or early 1662, Lower attended some of the Sedleian lectures and wrote out notes on them. In November 1662 Lower then made a transcription of some of the topics and sent it on to Robert Boyle, who was in London at the time.[54] About 1664 Lower also lent his notes to his fellow member of Christ Church, John Locke, who abstracted them into a commonplace book.[55] Even though Lower's notes themselves have not survived, we have, therefore, overlapping extracts among the Boyle Papers at the Royal Society,[56] and in John Locke's manuscripts at the Bodleian Library.[57] The link between the two became clear to me in 1969. I had read the extracts in Locke's commonplace book at Oxford. A few weeks later, while paging through thirty volumes of Boyle Papers in London, I came across an anonymous fascicle of Latin notes on medical topics. As I glanced through them, it struck me that they covered some of the same topics as the Locke notebook. A few hours' work comparing the text with the Locke extracts, and the handwriting with known samples of Oxonians, yielded the answer: this was Willis's work, and Lower was the writer.[58]

Clearly the Sedleian lectures, although Willis expressed some dissatisfaction with the early versions of them, were not treated by his circle of friends simply as a réchauffé of old ideas for adolescents. Nor were they.

[53] The Life and Times of Anthony Wood, Antiquary, of Oxford, 1632-1695, Described by Himself, ed. Andrew Clark (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1891-1900), 2: 161.

[54] Lower to Boyle, 26 November 1662, Works 6: 465.

[55] Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS. Locke f. 19, PP. 1-68 passim.

[56] Royal Society of London, Boyle Papers, XIX, ff. 1-35.

[57] The Locke manuscripts are described in P. Long, A Summary Catalogue of the Lovelace Collection of the Papers of John Locke in the Bodleian Library (Oxford: University Press, 1959) and in "The Mellon Donation of Additional Manuscripts of John Locke from the Lovelace Collection," Bodleian Library Record 7 (1964): 185-193. The existence of Locke's notes from Willis's lectures was first discovered by Kenneth Dewhurst, "Willis in Oxford: Some New MSS," Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 57 (1964): 682-687.

[58] When the late Dr. Dewhurst expressed an interest in editing the Willis lectures in MS. Locke f. 19, I called his attention to the complementary MS in Boyle Papers. Dewhurst's edition and translation of, and commentary on, the merged MSS appeared as Dewhurst, Willis's Oxford Lectures. I cite the lectures in that form unless there is a particular reason to refer back to the original Locke and Boyle manuscripts.

They contained many original and stimulating ideas—ideas that not only provided a program for neurological research but represented significant changes from Willis's very much more conventional earlier concepts. For example, in his casebook of the early 1650s he had attributed hypochondria to a faulty spleen and accepted the uterine origins of hysteria.[59] By the time he began lecturing, however, he had come to trace both to the brain.[60] Similarly with mania and "phantasy"; in the case-book Willis's descriptions reflect the traditional medical explanations,[61] whereas a decade later he had brought both of these conditions into the orbit of the nervous system.[62] In the lectures, then, Willis clearly outlined neurological explanations that, with only a few exceptions, he was to flesh out over the succeeding decade.[63] But one must also be aware of how skeletal this corpus originally was. The corpuscular details were very rudimentary. But even more significantly, Willis's explanations for brain function were insufficiently grounded in a firm and detailed knowledge of anatomy.

It is important, therefore, that we see clearly the academic, philosophical, and rather traditional origins of Willis's neurological research program, as well as its original incomplete state, because together they explain why a set of medical treatises should show a seemingly unmedical concern with the soul and its properties. Willis's medical practice over the previous fifteen years had provided him with an ever-increasing wealth of clinical experience, but no incentive whatsoever to analyze that experience systematically with respect to a long-standing tradition of thinking about the mind/body problem. But Willis, sincere in all things, took seriously his professorship, and the statutory injunctions about its subject matter. He confronted his own medical experience and ways of thinking about the physical world with the distinctly nonmedical and nonanatomical tradition of Aristotelian psychology—and these lectures were the result. Perhaps as important for the end result, Willis had to deliver his thoughts to an audience that included a number of his scientific cronies. One can hardly imagine a stronger incentive to casting the old psychology into new terms.

[59] Dewhurst, Willis's Oxford Casebook, 67, 93, 95.

[60] Dewhurst, Willis's Oxford Lectures, 87-92; Willis, Pathologiae cerebri, 144-193; Willis, "Pathology of the brain," 76-102.

[61] Dewhurst, Willis's Oxford Casebook, 127, 145.

[62] Dewhurst, Willis's Oxford Lectures, 66, 82, 96, 98, 122, 130-134.

[63] Dewhurst, Willis's Oxford Lectures, has correlated the topics of the lectures with the treatment of the same subjects later in Cerebri anatome, Pathologiae cerebri, and De anima brutorum.

I wish to argue further, however, that incitement was not of itself sufficient to get this new research program off the ground. Opportunity was needed as well. In the midst of an ever-busier practice, and lecturing responsibilities, Willis would most likely have had little chance to remake the speculations expressed in his Sedleian lectures, had he not been helped by a near-perfectly complementary collaborator: Richard Lower.[64] Ten years younger than Willis, Lower had come from both a higher social background and a better preliminary education than his mentor: respectively, the Cornish gentry and England's best public school of the period, Westminster School in London. In 1649 Lower had come up to Willis's old college, Christ Church, collected his B.A. and M.A. in due order,[65] and supervised students as the college's Censor in Natural Philosophy from 1657 to 1660.[66] He became interested in medicine in the early 1650s and started practicing about 1656. He soon thereafter began to work "under the directions of Dr Thomas Willis, to whose favour he recommended himself, by assisting him in his anatomical dissections."[67] Lower continued to practice as Willis's junior medical partner until he left Oxford in 1665.[68]

[64] For Lower's life and scientific activities, see Frank, Harvey and the Oxford Physiologists, passim, but especially 64-65, 174-220, and the sources therein cited. The best brief overview of Lower's life is Theodore Brown, "Richard Lower," Dictionary of Scientific Biography 8:523-527.

[65] Lower was elected into a Studentship from Westminster in 1649 and seems to have come to Oxford then, although he did not actually matriculate until 27 February 1651; he proceeded to the B.A. on 17 February 1653 and to the M.A. on 28 June 1655 and accumulated his degrees of B. and D.Med. on 28 June 1665, just before leaving Oxford: Foster, Alumni Oxonienses 3: 943. It was not unusual for fellows of colleges to practice before formally taking their degrees.

[66] Chapterbook (1649-1688), pp. 77, 88, 104, Chapter Archives, Christ Church, Oxford. Lower also served as Praelector in Greek for 1656-57. Occupying one of the positions as a Student (the equivalent of a Fellow in other colleges), he rose in seniority within Christ Church until about 1662, when he reached the top of those not in orders. Then, having as he said to Boyle insufficient "favour or friendship" to obtain one of the two physician's places in the college, he could not keep his Studentship. He did, however, continue to occupy rooms in the college. See Richard Lower to Robert Boyle, 24 June 1664, Works 6: 474.

[67] Biographia Britannica (London, 1747-1766), vol. 5, col. 3009.

[68] For example, in September 1662 Willis and Lower treated one of John Locke's tutees; Willis got a one-pound fee, and Lower ten shillings: Bodleian Library, MS. Locke f. 11, f. 24r. Lower was sent out to the country—once as far as Cambridgeshire—to attend Willis's patients: Richard Griffith, A-la-mode phlebotomy no good fashion (London, 1681), 171. On the return journey of one such trip into Northamptonshire in April 1664 Lower discovered the medicinal character of the waters of Eastrope, Oxfordshire, near King's Sutton, which he and Willis then promoted as a local spa: Wood, Life and Times 2: 12.

But Lower's real interest, as suggested by the activity that brought him together with his mentor, was not so much clinical medicine as anatomy and physiology. He seems to have had an inveterate itch to cut things up. The first surviving piece of evidence about his scientific interests, written by John Ward in his commonplace book about October 1660, pictures him vividly: "Mr. Lower cut a doggs windpipe and let him rune about: hee had a week so: he could note smell but would eat any thing I was told."[69] Lower's curiosity naturally expressed itself in exploring the detailed structure, the precise workings of a living thing. As his later work on the heart, Tractatus de corde (1669), showed, he had little interest in broader questions of matter-theory and principles of life. His was a reputation as a dissector and vivisector; his friend, Anthony Wood, was not at all surprised to arrive at Lower's rooms in Christ Church one Sunday morning and find him busily dissecting a calf’s head.[70] Lower's personality fit his avocation. He seems to have been anti-High Church, politically a Whig, temperamentally exacting, and—if later testimony is to be credited—inclined to be arrogant about his scientific knowledge.[71]

Willis, a contrast in personality and background, equally contrasted with Lower in having no such eager knife. Before 1660 he actively pursued chemistry but did little anatomy. Of fifty patients whose treatment is recorded in his casebook from the early 1650s, ten died, and on only one was a cursory postmortem performed; even in that case the phrasing of the notes seems to hint that it was a surgeon, not Willis, who did the necropsy.[72] Although the only official university teaching post in anatomy, the Tomlins Readership, changed hands several times during Willis's residence in Oxford, there is no indication that he sought the position.[73] His first book, the Diatribae duae medico-philosophicae of 1659, reports no postmortems, and of the numerous scattered references to Willis to be found in published works, diaries, and correspondence be-

[69] Ward, "Diary," VII, f. 83r.

[70] Wood, Life and Times 2: 4.

[71] Frank, Harvey and the Oxford Physiologists, 283 and sources cited there.

[72] In Dewhurst, Willis's Oxford Casebook, deaths are recorded on pp. 74, 80, 91, 97, 100, 105, 118, 122, 127, 132. The only postmortem was carried out on F. Symmons (118); the phrasing seems to imply that Willis only did the chemical examination of fluids:

In the dead body it was found that the lungs were floating in a large quantity of water which was enclosed in the saepta of the thorax.

Moreover when we evaporated some of this water with slow heat on sand there was, in the bottom of the vessel, a residuum like mucus or flour porridge and whites of egg, viscous and smelling adominably.

[73] On the Tomlins Readership, see Wood History and antiquities 2: 883-884.

fore 1660, only one links him to an anatomical proceeding. This is the renowned "resurrection" of Anne Green in December 1650, in which Petty, Willis, Bathurst, and others assembled to dissect the body of a hanged convict, only to find the proposed cadaver very much alive.[74] But on this occasion it was not Willis but Petty, a skilled dissector trained in Leiden, who took the lead.[75]

But Lower's presence at Oxford, and especially in Willis's coterie, provided the opportunity. Lower reported the start of the project in a letter to Boyle in January 1662:

The doctor was not at leisure till of late to make those dissections of the brain, which he hoped; but at length we have had the opportunity of cutting up several, and the doctor, finding most parts of the brain imperfectly described, intends to make a whole new draught thereof, with the several uses of the distinct parts, according to his own fancy, seeing few authors speak any thing considerable of it.[76]

Thus began an intense period of dissections in which "no day almost past over without some Anatomical administration; so that in a short space there was nothing of the Brain, and its Appendix within the Skull, that seemed not plainly detected, and intimately beheld by us."[77] Entire "hecatombs" of animals, Willis said, were slain in the anatomical court.[78] They dissected not only human cadavers but horses, sheep, calves, goats, hogs, dogs, cats, foxes, hares, geese, turkeys, fishes, and even a monkey. The indefatigable worker was Lower, the "edge of whose Knife and Wit" Willis gratefully acknowledged for assistance in "the better searching out both the frames and offices of before hidden Bodies."[79] Others of the club helped out. John Wailis, the mathematician, and a longtime club member, participated in some of the initial dissections.[80] The physician Thomas Millington and the mathematician Christopher Wren, both con-

[74] The incident is described in [Watkins], Newes from the dead, 2d ed. (Oxford, 1651), 1-8. Petty also described the resurrection in a letter to Samuel Hartlib, 16 December 1650: Hartlib Papers, Bundle VIII (23).

[75] Petty was appointed Tomlins Reader on 31 December 1650, about two weeks after the Anne Green affair. His anatomical work at Oxford is reflected in volume 3 of the Petty Papers (now at Bowood House, Clan, Wiltshire), which contain his medical and anatomical lectures at Oxford c. 1650-1652. For details, see Frank, Harvey and the Oxford Physiologists, 101-103.

[76] Lower to Boil, 18 January 1661[/2], Works, 6: 462.

[77] Willis, Cerebra anatome, sig. a2v; "Anatomy of the brain," 53.

[78] Ibid., sig. A4r and 51.

[79] Ibid., sig. a2v and 53.

[80] Wallis's presence at a brain dissection is mentioned in Lower to Boyle, 18 January 1661[/2], Works 6: 463. Cf. also John Wallis to Henry Oldenburg, 17 February 1673, The Correspondence of Henry Oldenburg, ed. and trans. A. Rupert Hall and Marie Boas Hall (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1965-), 9:466, in which Wallis shows an intimate knowledge of Willis's Cerebri anatome.

temporaries of Lower's at Westminster, and by then at All Souls, "were wont frequently to be present at our Dissections, and to confer and reason about the uses of the Parts." Millington especially was Willis's sounding board, to whom he proposed almost daily his "Conjectures and Observations."[81] Within ten months Lower could send to Boyle the extracts of Oxford lectures, and report that the "doctor hath now perfected the anatomical part likewise, but being not satisfied in some things," might not soon be induced to publish.[82] By April of 1663, however, Willis and Lower were "wholly diverted" with more dissections, which were "very near finished" because Willis intended to put the book into the press by midsummer.[83] Within the next few months Wren had, as Lower reported to Boyle, "drawn most excellent schemes of the brain, and the several parts of it, according to the doctor's design," and Willis was resolved "to print his anatomy forthwith."[84] Lower carried the same news personally to London in July. He missed presenting Willis's service to Boyle, but told his old Westminster schoolfellow Robert Hooke that Willis's book "is within a little while to come forth, and he added, that Dr. Wren had drawn the pictures very curiously for it."[85] A "little while" and "forthwith" were faster in the seventeenth century than today, and the book came out six months later.

To those wishing to assign credit for the Cerebri anatome, the role of Lower especially has posed some problems. Anthony Wood, in his capsule biography of Willis, noted of the Cerebri anatome : “Whatsoever is anatomical in that book, the glory thereof belongs to the said R. Lower, whose indefatigable industry at Oxon produced that elaborate piece."[86] Twentieth-century scholars have noted that Lower was a frequent drinking chum of Wood,[87] that Wood later had a land dispute with Willis,[88]

[81] Willis, Cerebri anatome, sig. a3r: "Anatomy of the brain," 54.

[82] Lower to Boyle, 26 November 1662, Works 6: 465·

[83] Lower to Boyle, 27 April 1663, Works 6: 466.

[84] Lower to Boyle, 4 June 1663, Works 6: 466.

[85] Robert Hooke to Robert Boyle, [3 July 1663], Works 6: 487.

[86] Wood, Athenae, vol. 3, col. 1051; see also the comment to similar effect in Wood's biography of Lower, ibid., 4: 297.

[87] Dewhurst, Willia's Oxford Lectures, 13, 32. Wood's references to eating or drinking with Lower are in Wood, Life and Times, vol. 1: (1657) 30; (1658) 259; (1659) 266, 267, 279, 284; (1660) 313, 318, 321, 327; (1661) 405, 410; (1662) 428, 430, 444, 450; (1663) 471, 474,477, 486, 487, 501, 503, 507; vol. 2: (1664) l, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 14, 15, 23, 24; (1665) 27, 31, 33, 35, 37, 40, 43; (1666) 71, 73, 76; (1667) 99.

[88] Dewhurst, Willis's Oxford Lectures, 33.

and finally that Wood's judgment was taken almost word for word from one of Henry Stubbe's blasts against the Royal Society.[89] They have therefore tended to discount Lower's participation in the research and to credit Willis with everything.[90] Such a judgment is untenable and unnecessary. Stubbe and Wood were admirers of both Willis and Lower and merely wished to recognize the interdependence of the two.[91] In reality, the collaborative relationship was quite complex. Clearly Willis provided the impetus; from the very beginning Lower's letters remarked how "the doctor" suggested, and participated in, this or that aspect of the brain dissections.[92] Moreover, Willis's concepts seem to have directed the interpretation of the findings, as for example when Willis showed Lower "several times" how the dissections supported "his opinion of the use of the cerebellum for involuntary motion." Similarly with the medullary and cortical parts of the cerebellum, and the origins of the optic nerves.[93] The degree of collaboration could vary from day to day. Lower often wrote in letters of dissections, postmortems, and experiments that

[89] The argument of the biased testimony of Wood was first made by Sir Charles Symonds, "The Circle of Willis," British Medical Journal (15 January 1955), i, 119-124, especially 121. It has been accepted by: William Feindel, "Thomas Willis (1621-1675)—The Founder of Neurology," Canadian Medical Association Journal 87 (1962): 289-296, especially 289; and Islet, Willis [1968], 33-34. Wood's phrase was taken almost verbatim from Henry Stubbe, The plus ultra reduced to a non plus (London, 1670), 95, where Stubbe is attempting to refute Joseph Glanvill's claim of anatomical novelties to be found in Willis's Cerebri anatome. Stubbe wrote further that Willis did not lack abilites but that because of his great practice, he did not have leisure to attend the dissections. All that Willis contributed, Stubbe heard, was the "discourses and conjectures" upon Lower's anatomical deductions; these were ingenious, but they were not inventions in the sense that Glanvill wished to claim.

[90] Dewhurst, Willis's Oxford Lectures, 13.

[91] For most of his career, Stubbe was a great admirer of Willis. See for example, his praise for, and use of, Willis's ideas in: The Indian nectar; or, A discourse concerning chocolata (London, 1662), dedication to Willis, sigs, a2r-v, whom he calls second only to Harvey, pp. 124-125; The miraculous conformist (Oxford, 1666), prefatory epistle to Willis, sigs. A2r-A3v, pp. 14, 18-19, 29; Legends no histories (London, 1670), 64-65, 79; An epistolary discourse concerning phlebotomy ([London], 1671), 8, 44-48, 110, 114-115, 119, 172-240. Moreover, even in The plus ultra reduced, 178, Stubbe was willing to grant that Willis did "propose new matter for improving the discoveries, and put Dr. Lower upon continued investigation, thereby to see if Nature and his Suppositions did accord; and although that many things did occur beyond his apprehension, yet was the grand occasion of that work, and in much the Author." Stubbe had an excellent collection of medical books, which included all the works of Willis and Lower, and many of Boyle's: cf. British Library MS. Sloane 35, ff. 6r, 8r, 9r, 12r-13r, 15r' 16r, 17r-18v, 20r.

[92] Lower to Boyle, 18 January 1661[/2], Works 6: 469,463; Lower to Boyle, 4 June 1663, ibid., 467, 468; Lower to Boyle, 24 June 1664, ibid., 470-471.

[93] Lower to Boyle, 18 January 1661[/2], ibid., 462, 463.

"we" did. In other circumstances he mentioned times when "I tried an experiment for Dr. Willis."[94] On yet other occasions he reported instances of his own dissections and experiments, although these are almost invariably not on the nervous system. Willis and Lower, at least, seem to have been quite clear about the mutually distinct, but symbiotic collaborative roles that they occupied. Willis needed Lower's results and continuing efforts as much as Lower needed Willis's direction, facilities, and literary follow-through. And both needed Wren's drawings, which visualized and encapsulated the highly detailed written description in the text.

It is important to realize this cooperative nature of the Cerebri anatome, and to a lesser extent Willis's later work, because such origins explain the recurring puzzlement that commentators have felt when confronted with his books. They are vocal in their praise of the accuracy of the anatomy and the quality of the illustrations, are intrigued by the localizations proposed, are repelled by the fancifulness of the hypothetical mechanisms described, are befuddled by the corpuscular language in which they are expressed, and are bemused by the therapies counseled.[95] It always seems as if Willis is trying to do too much. But if one views Willis's neurological works as products rather of many minds, each with a different forte, then the reason for this synthetic quality becomes clear. Indeed, given the history of small-scale cooperative ventures in research at Oxford, the very model upon which the Royal Society was originally founded, this synthetic quality should be expected.

THE SOUL ON THE DISSECTING TABLE

Thus far I have characterized the biographical trajectory from which Willis's neuroanatomy and neuropsychiatry arose, and the process through which his research program was launched and carried forward within his Oxford circle. What did Willis and his confreres do once they attempted to put the animus under the dissecting knife? What were the axioms, the assumptions, the heuristic principles—the moves, or tactics —through which a new view of brain and soul was worked out? By assumptions or principles, let me reiterate, I do not mean his specific conclusions in neuroanatomy, neurophysiology, or neuropsychiatry, although I will have occasion to look closely—albeit selectively—at these

[94] Lower to Boyle, 24 June 1664, ibid., 470.

[95] Even one of Willis's admirers, Isler, speaks of "the combination of epoch-making scientific ideas and discoveries with reckless speculation and overt nonsense which is typical of Willis' books " (Thomas Willis [1968], 106).

concepts.[96] I mean instead his ways of reasoning in order to reach those conclusions. Seldom does Willis set these out explicitly, with a full and clear explanation. They must rather be extracted from his actual processes of reasoning, as they are laid out in his lectures and books.

The first such principle was a methodological one: the initial and seemingly thoroughgoing separation of what later generations would call "mind" into two kinds of soul, the rational and the animal.[97] Willis took the outline of this distinction most immediately from Gassendi, although he argued that it had also been held by St. Jerome and St. Augustine among the ancients, and Henry Hammond among his own

[96] For detailed discussions of one or another aspect of Willis's ideas in neurology and neurophysiology, see the following (arranged chronologically); Jean Vinchon and Jacques Vie, "Un maître de la neuropsychiatrie au XVII siècle: Thomas Willis (1662[sic]-1675)," Annales médico-psychologiques 86 (1928): 109-144; Donal Sheehan, "Discovery of the Autonomic Nervous System," Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry 35 (1936): 1081-1115, especially 1085-1089; Paul F. Cranefield, "A Seventeenth-Century View of Mental Deficiency and Schizophrenia: Thomas Willis on 'Stupidity or Foolishness,'" Bulletin of the History of Medicine 35 (1961): 291-316; Raymond Hierons and Alfred Meyer, "Some Priority Questions Arising from Thomas Willis's Work on the Brain," Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 55 (1962): 287-292; Alfred Meyer and Raymond Hierons, "A Note on Thomas Willis's Views on the Corpus Striatum and the Internal Capsule," Journal of the Neurological Scierices 1 (1964): 547-554; Raymond Hierons and Alfred Meyer, "Willis's Place in the History of Muscle Physiology," Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 57 (1964) 687-692; Raymond Hierons and Alfred Meyer, "On Thomas Willis's Concepts of Neurophysiology," Medical History 9 (1965): 1-15, 142-155; Edwin Clarke and C. D. O'Malley, The Human Brain and Spinal Cord (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1968), 158-162, 333-390, 388-390, 472-474, 582-585, 636-640, 723-726, 775-779; Isler, Thomas Willis [1968], 88-141, 148-182; Kenneth Dewhurst, "Willis and Steno," Analecta medico-historica 3 (1968): 43-48; Elvira Aquiola, "La lesion nerviosa en la obra de Th. Willis," Asclepio 25 (1973): 65-93; Yvette Conry, "Thomas Willis, ou la premier discours rationaliste en patholgie mentale," Revue d'histoire des sciences 31 (1978): 193-231; John D. Spillane, The Doctrine of the Nerves: Chapters in the History of Neurology (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981), 53-107; Kenneth Dewhurst, "Thomas Willis and the Foundations of British Neurology," in Historical Aspects of the Neurosciences, ed. F. C. Rose and W. F. Bynum (New York: Raven, 1982), 327-346; Adolf Faller, "Die Pr paration der weissen Substanz des Gehirns bei Stensen, Willis und Vieussens," Gesnerus 39 (1982): 171-193; Richard U. Meier, "'Sympathy' in the Neurophysiology of Thomas Willis," Clio medica 17 (1982): 95-111. Hierons and Meyer [1965] has a very full bibliography and provides the best entrée into the older literature on Willis's neuroanatomy and neurophysiology.

[97] Although the notion of the corporeal soul was adumbrated partially in the Sedleian lectures, it was not stated clearly until the Cerebri anatome. See Dewhurst, Willis's Oxford Lectures, 125-129; Willis, Cerebri anatome, 133-134, 253; "Anatomy of the brain," 95, 130; Willis, De anima brutorum, sig. A2r-v, b1v-b4v, pp. 1-16; Soul of brutes, sig. A2v, A3v-A4v, pp. 1-6

[98] Willis, De anima brutorum, sig. A2v, pp. 7-8. 115-119; Soul of brutes, sig. A2v, pp. 4, 40-42.

contemporaries.[98] According to this distinction, the characteristics of the rational soul were relatively straightforward: it reasoned and judged; it was immortal and possessed by man alone.[99] The animal soul, which he also called the corporeal soul, or anima brutorum, was possessed by both man and the animals, and in the case of man was subservient to the rational soul.[100] Logically, the distinction between the two was sharp and clean. In actuality, as we shall see, the corporeal soul came to take on a complexity of meaning and function such as to infringe significantly on the autonomy of the rational soul.

Was this supposition of a corporeal soul merely a ruse, a quasi-Cartesian device to avoid confrontation with church authorities? The very piety of Willis's life should refute any implication of devious intentions. Nor did the church see danger; his three major neurological works, the Cerebri anatome, the Pathologiae cerebri, and De anima brutorum, were dedicated to Sheldon, his good friend, patient, and Archbishop of Canterbury. Each book carried the "Imprimatur" of the highest scholarly and religious official of the University of Oxford, the Vice-Chancellor; in two of these cases, that was Willis's brother-in-law, John Fell. Willis's attachment to the distinction between the rational and the corporeal soul arose rather, I believe, from his pressing desire to see man in a way that squared with his own experience as a clinician and scientist. For years he had looked at patients and seen bodies capable of multifarious derangements, of which the most interesting seemed to stem from the brain. Yet to see most of these functions and dysfunctions as proceeding from the traditional, unitary, soul was repugnant to his belief that anatomy could be pictured in chemical, corpuscular terms and could be manipulated by treatment for the benefit of the patient. Moreover, if one ascribed all human mental phenomena to the rational soul, then diseases of the body could be thought to derange that which was immortal in a human being: his reason and will. This verged on blasphemy. Indeed, Willis felt strongly that the dignity of the rational soul was actually vindicated by believing in its corporeal servant.[101] I am led to conclude that the anima brutorum, if it served as a device for any purpose, functioned to give meaning to Willis's integrated life as devout churchman, clinician, and scientist.

Willis conceived the corporeal soul, in its turn, to be composed of two parts: the vital soul lodged in the blood, and the sensitive soul seated in

[99] Willis, De anima brutorum, sigs. b3v-b4r, pp. 96-99, 110-124; Soul of brutes, sig. A4r, pp. 32-33, 38-44·

[100] Willis, De anima brutorum, 87-109; Soul of brutes, 29-38.

[101] Willis, De anima brutorum, 2; Soul of brutes, 2.

the nervous system.[102] For our purposes here we need know about the vital soul only that Willis conceived it as a kind of "flame" in the circulating blood, which was fed by the nitrous, active particles from the air absorbed in respiration. Through a mutual agitation of these nitrous aerial particles with the sulphureous, spirituous, and saline particles of the blood—a process which Willis more and more firmly identified as a "fermentation"—the vital soul generated heat, assimilated digested food, and maintained the body parts.[103] In contradistinction, the sensitive soul consisted of the movement and agitation of particulate animal spirits within the brain and nerves. It was linked to the vital soul because these particles of animal spirits in the nervous system were extracted from the most subtle and active spirits of the blood.[104] The sensitive soul lodged in the nervous system was the part of the corporeal soul most directly subservient to the rational soul, since it was only through the sensitive soul that sensation and movement could take place.

The second implicit axiom of Willis's neurological reasoning related these subtle and active particles of animal spirit to the perceived differences of anatomical texture in the nervous system, and in turn correlated these textural differences with differences in function. Willis emphasized, as few did before him, that the substance of the nervous system was of three distinct types: the gray cortical masses (both cerebral and cerebellar), the white medullary structures, and the long, thin peripheral nerve bundles. He and his collaborators noted the consistent way in which blood vessels encased both cerebral and cerebellar cortices, running inward, and deduced that this first type of texture, cortex, must therefore serve to separate animal spirits from the blood for use by the nervous system.[105] The image that recurred again and again in interpreting this anatomical relationship was the chemical alembic: the cortex "distilled" the finest spirituous particles out of the blood.[106] The second set of neural elements, the deeper, white, medullary structures, whether

[102] Willis, Cerebri anatome, 133-134; "Anatomy of the brain," 95; Willis, De anima brutorum, 9-33, 69-70; Soul of brutes, 4-7, 22.

[103] The concept of the vital soul was mentioned briefly in Cerebri anatome, 133; "Anatomy of the brain," 95, but was not developed fully until De sanguinis accensione in 1670, and De anima brutorum, 12-72; Soul of brutes, 6-23.

[104] The sensitive soul seems to have been the first of these linked concepts to emerge in any clarity: Dewhurst, Willis's Oxford Lectures, 67, 125-129, 132; Willis, De anima brutorum, 72-77; Soul of brutes, 23-24.

[105] Dewhurst, Willis's Oxford Lectures, 63; Willis, Cerebri anatome, 109 -113, 125-126, 187-194; "Anatomy of the brain," 87-89, 92, 110-113; Willis, De anima brutorum, 72; Soul of brutes, 23.

[106] Willis, Cerebri anatome, 83-84; "Anatomy of the brain," 79.

of cerebrum, brain stem, or cerebellum, received the animal spirits and provided the tracts and labyrinths within which these particles exercised their functions.[107] The third part of the nervous system, the peripheral nerve structures such as cranial nerves, spinal nerves, and the nerve plexi linked to the brain, all served as grand highways for the action of the spirits to be propagated over a long distance. Although all three textures of the nervous system were solid, this was no impediment to the movement of subtler particles. They could flow through the liquid/ solid matrix that was created by the grosser classes of particles, such as earth and water. Although Willis himself does not use the image, one can visualize the relationship as a stream of water flowing through a solid mass of gravel. Certainly Willis had this picture in mind when he thought of the peripheral nervous system; he had examined cut cross-sections of nerves and always found them solid, but felt that spirits could percolate through the nerve none the less.[108]