The Heroön

Excavation of the Heroön took place in 1979, 1980, and 1983. The area had been greatly disturbed by agricultural activity in the Early Christian period and later; the effects can still be seen in the foundation stones scarred by plowing.

Three phases of construction can be distinguished in the Heroön: early Archaic, late Archaic, and early Hellenistic.

The Hellenistic Structure

The early Hellenistic phase is the one most visible today (Fig. 34). This latest structure took the shape of a lopsided pentagon, its outline possibly influenced by construction here during the late Archaic period. The south and east walls were set at right angles, more or less, to each other. The north and west walls were set at oblique angles, with a change in direction at the southern end of the west wall.

The north wall is just over 30 m. long and has four buttresses at intervals along its interior face. The east wall was originally 22.35 m. in length, but more than half of it was destroyed long ago by a shift in the course of the Nemea River. Ironically, the southern portion of the east wall is the best-preserved part of the Heroön, with five of the original reddish limestone orthostates still in position. The dimensions of the orthostates average 0.48 by 0.92 m., with a height of about 0.50 m. The south wall, slightly more than 36.50 m. long, has four interior buttresses. The west wall heads north for 4.50 m., then veers northeast for 25.50 m. to join the north wall. There were also four interior buttresses for the west wall.

For the most part, only the foundations of the Hellenistic Heroön are still extant. These are cut from a soft yellow poros, a malleable stone which deteriorates quickly when exposed to the elements. The average foundation block is 0.65

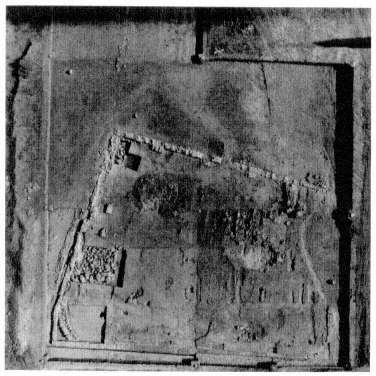

Fig. 34.

Plan of the Heroön, with phases.

by 1.25 m. At fairly regular intervals, blocks made of this same material project inward from the wall foundations, apparently as underpinnings for buttresses or the like. The actual wall above the foundations was no thicker than 0.50 m. to judge from robbing trenches and the next higher course of orthostates preserved at the southeastern corner of the enclosure.

The foundations supported a high fence, probably of stone, rather than a structural wall. The Heroön seems to have been unroofed; no interior roof supports have been found, and such supports would have been needed in such a large building. The structure is also strangely shaped to accommodate conventional roofing. In addition, there is some evidence for

Fig. 35.

Perspective view of the restored Heroön from the northeast.

trees having grown inside the Heroön, so perhaps we should think of a fence surrounding a grassy, sylvan area. Several stone blocks firmly positioned in the open area of the Heroön should perhaps be identified as individual altars (Fig. 35). This matches Pausanias's description of altars and the tomb of Opheltes within the enclosure. The tomb itself might have been a construction northeast of the center of the enclosure. Although now little more than a small, roughly aligned enclosure surrounded by fallen stones, this was once a rectangular structure measuring about 1.40 by 3.15 m. It was erected as part of the late Archaic phase and may have Continued in use dung the 4th century and following, perhaps functioning much as did the so-called Leokorion in the Athenian Agora.[59]

[59] See the description and references given in H. A. Thompson, ed., The Athenian Agora (Athens 1976) 87-90.

The entrance to the Heroön was at the northeastern corner facing the Temple of Zeus, where poorly preserved foundations for a monumental porch or gate stand outside the north wall. Measuring approximately 1.00 by 4.50 m., this porch was perhaps roofed over with curved Lakonian tiles, many small fragments of which were found at this place.

The area of the enclosure seems to have been cleared and leveled for a new construction phase in the late 4th or early 3rd century B. C. Traces of the ritual inauguration of the renovated shrine can be seen in the burial of a pot against the north wall and its easternmost buttress. When excavated, this vessel contained a greasy, dark brown earth. This may once have been the pulse (boiled beans) and vegetables inside what Aristophanes described as installation or dedication pots (see museum case 4, p. 28, and n. 24). The Hellenistic chronology of the Heroön's latest phase makes the enclosure roughly contemporary with the new construction of the Temple of Zeus and the other post-Classical building activity at Nemea.

The Late Archaic Structure

The strange shape of the Hellenistic building may be due to the irregular dimensions of the late Archaic construction since the foundations of this earlier building provided additional support for the 3rd-century structure. This sequence is particularly clear on the western side of the building where the rubble courses of the Archaic phase more or less underlie the Hellenistic ones. The two walls diverge slightly in the southwestern corner, with the earlier wall forming a curve instead of an actual corner (Fig. 36).

Other traces of the late Archaic enclosure have been uncovered beneath and perpendicular to the preserved portion of the Hellenistic east wall near its southern end. The foundations of this enclosure, formed of two courses of unshaped

rough stones, were considerably less formal than those of the later phase. They may have supported a mud-brick wall, protected on top by the tiles found in excavation. As yet no evidence for doors or gates has been uncovered. Although greater chronological precision is not possible, this phase can be dated to the second half of the 6th century B.C.

Inside the late Archaic Heroön was the rectangular structure made of large boulders placed on edge (see p. 106). The large amounts of ash, bone, and apparently votive deposits associated with this structure suggest cult activity—possibly an altar or, as already suggested, the tomb of Opheltes.[60]

The Early Archaic Structure

Remains of a yet earlier Archaic phase (in the first half of the 6th century B.C. ) can best be seen in the southwestern comer of the enclosure, where stone foundations of ashlar masonry are cut by, and therefore predate, the curvilinear rubble wall of late Archaic construction. Other features that may be connected with this phase lie further north along the west wall. A jumbled mass of rocks near the midpoint of the wall may have been left over from the dismantling of the early wall, then used as packing for later landscaping. More of these large unworked stones lie under the northwestern corner of the Heroön.

There is a sharp contrast between the cut poros foundation blocks from the southwestern comer and the unaligned, unworked stones to the north. What sort of activity took place here during the early Archaic period? Were there two different structures? Was the same function involved? The present

[60] This is not to say that an actual burial was located here; rather, it was a legendary one; no evidence of human burial has been uncovered at the Heroön. Such cenotaphs were common in antiquity, e.g., the "Tomb of Achilles" at Elis attested by Pausanias 6.23.3 and 24.1.

Fig. 36.

Aerial view of the Heroön, 1980.

state of the evidence does not allow us to answer these questions easily.

The early Archaic phase can be dated to the first half of the 6th century, around the time traditionally given for the establishment of Nemea as a site for Panhellenic athletic contests. Apparently the earliest "Heroön" had been in existence for about fifty years when the late Archaic enclosure was constructed.

Pausanias described the Heroön of Opheltes near the Temple of Zeus at Nemea as a

surrounding the tomb of the child. He used this particular phrase in four other instances, including his accounts of the shrines of Ino-Leukothea at Megara and of Pelops at Olympia.[61] The Pelopion has been excavated, and the information thus gained has been useful in reconstructing the Heroön at Nemea.[62] The function of the two structures, after all, was the same: to monumentalize and sanctify the tomb of a dead hero.

The identification of this area as the hero shrine of Opheltes has already been discussed (pp. 27-29). Although the Pelopion at Olympia occupies a central location in the sanctuary near the Temple of Zeus, here at Nemea the shrine to the hero whose mythical death is central to the foundation story of the games lies on the periphery of the Sanctuary of Zeus. The topography thus illustrates and emphasizes the extent to which Zeus dominated the games, the sanctuary, and the baby-hero. Nonetheless, the scale of the Heroin and the quantity of the dedications discovered within it show that the cult of Opheltes enjoyed a fair popularity.