Three

The Decision Makers

Preoccupied with the governed classes, European social historians have not shown as much curiosity about the governing classes, not even about the new elite of businessmen and salaried managers emerging in the nineteenth century. Their career trajectories, responsibilities, compensations, family backgrounds, and outlooks await serious analysis.[1] The PGC, as one of France's early corporations, provides an opportunity to study salaried managers just as they came to form a distinct socioprofessional category. Corporate management was not yet a familiar activity and lacked clear-cut norms and prescriptions when the firm was founded. Only railroad companies and a few other large enterprises existed to serve as models.[2] In truth, their example was only marginally useful to decision makers at the PGC. Corporate forms and practices arose gradually within the gas company, partly through trial and error. The model of the bureaucratic state proved highly influential, too. Such were the forces molding a powerful, new economic elite.

The Administrative Hierarchy

The statutes of the PGC laid down once and for all and with Cartesian clarity the lines of authority that were supposed to direct the firm. Given

[1] For one rare study of these questions, see Maurice Lévy-Leboyer, "Hierarchical Structure, Rewards, and Incentives in a Large Corporation: The Early Managerial Experience of Saint-Gobain, 1872-1912," in Recht und Entwicklung der Grossun-ternehmer im 19. und frühen 20. Jahrhundert, ed. Norbert Horn and Jürgen Kocka (Göttingen, 1979), pp. 451-472.

[2] The importance of railroads in establishing patterns in corporate management is a well-known theme. See Alfred Chandler, "The Railroads: Pioneers in Modem Corporate Management," Business History Review 39 (1965): 16-40, and The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business (Cambridge, Mass., 1977). A few of the PGC's early executives had worked for railroads, but it is doubtful whether that experience was formative.

the weight of French tradition, one might expect those lines to have been highly centralized, and they were. The nature of the executive at the center, however, changed several times over the life of the firm. Furthermore, the concentration of authority proved far greater in principle than in reality, the result of both choice and circumstance. The PGC was not so inflexible as to have faced all its challenges without structural innovation. It responded to the environment with new managerial approaches and tolerated even a good deal of ambiguity about lines of authority. Of course, such flexibility did not in itself guarantee wise or appropriate decision making.

Sovereignty over the firm was vested in the stockholders, but they immediately delegated their authority to a conseil d'administration, or board of directors, composed of twenty elected shareholders. Meeting faithfully at least once a month for the fifty-year life of the firm, board members envisioned for themselves a supervisory role.[3] No decision would have force without their approval, but they declined to be the managers of the corporation. Instead, the very first board, led by the owners of the merging gas companies, decided on a collective executive. The board created a five-member executive committee (comité d'exécution ) made up of rotating board members. Each member was to oversee a set of operational departments. Though the committee's name implied the passive role of carrying out the wishes of the board, the committee was actually the governing force—until the need for further change became evident.[4]

The owners of the new gas firm quickly found a collective executive too cumbersome. The first year of business brought vast new opportunities, the beginning of daytime consumption, shortages, confusion, and the need to plan for expansion. An executive committee composed of parttime managers preoccupied by interests outside the firm could not deal seriously with pressing matters. Besides, they received compensation for their tasks essentially as stockholders, through dividends. The need for a full-time chief executive who would receive ample compensation for his services to the gas company alone was manifest. In November 1856 Louis Margueritte, an owner of one of the merging firms and an influential board member, proposed the creation of the office of director. The incum-

[3] The deliberations of the board are in AP V 8 O nos. 723-737.

[4] Ibid., no. 723, deliberations of January 11, 1856. The records of the executive committee are in nos. 665-700.

bent would provide leadership and implement all the decisions approved by the board and executive committee. These two bodies would continue to meet (in the case of the committee, as often as once a week), with the director presiding. He would also have the power to choose the committee members.[5] Thus the office became the central one in the firm even though the director was not absolute master. As the PGC grew larger and more complicated and as board members grew more distant from the gas industry, the director assumed the role of the company's animating force. On matters of potential controversy it is likely that the director was careful to consult with influential board members and build a consensus in the executive committee. In any case, minutes of the committee meetings show virtually automatic confirmation of the director's proposals.

With the appointment of a director before the first year of operation was over, the PGC would seem to have joined the ranks of the new breed of firm, still rare in France and Europe, run by a salaried manager rather than by the owner.[6] Yet this was not quite the case, at least for a while. The board of directors offered the post of director to Margueritte, but he turned it down. Another board member, Vincent Dubochet, took the position. He, like the board's first choice, had been an owner of one of the pre-merger gas companies and a founder of the PGC. Both were among the largest stockholders. Whether the board fully intended the choice to set a precedent for future appointments is unclear, but the selection of Dubochet as director was only half a step away from the owner-manager. Accentuating the incomplete transition to a new form of management was the board's failure to establish a salary for the new director until a year after his appointment.[7] The definitive move to a salaried director came with Dubochet's retirement in 1858, when the board entrusted the fate of the firm to an officer of the prestigious Corps des Ponts et Chaussées (Corps of Bridges and Roads). An annual salary of twenty thousand francs, supplemented by a generous profit-sharing bonus, was established immediately.[8] The chief executive in the PGC was no longer a collective entity nor an owner-founder but rather a graduate of France's most illustrious technical institutions and a member of a national administrative elite. Though salaried directors of corporations were soon to become com-

[5] Ibid., no. 723, deliberations of November 20, 27, 1856.

[6] For a historical survey of large corporations in Europe, see Herman Daems and Herman Van Der Wee, eds., The Rise of Managerial Capitalism (Louvain and The Hague, 1974), and Alfred Chandler and Herman Daems, eds., Managerial Hierarchies: Comparative Perspectives on the Rise of the Modern Industrial Enterprise (Cambridge, Mass., 1980).

[7] AP V 8 O , no. 723, deliberations of April 30, 1857.

[8] Ibid., deliberations of May 1, 1858.

monplace, appointing one was not yet routine when the PGC was founded.[9] The firm had spent three years groping toward such an office as a solution to its executive needs.

The central office retained essentially this form throughout the rest of the company's history, but there were some adjustments. The post of assistant director was added in 1860 to help carry the growing burden of administration. The director's position also suffered a temporary demotion between 1892 and 1901. In an effort to deal with labor demands from city hall and with the threat of unions, the board appointed a well-known advocate of industrial reform to the directorship. It seems clear, though, that the person he replaced, Emile Camus, remained in command. Immediately upon resigning as director, Camus was named delegated board member, charged with "a superior control over all services." Camus received higher pay than the new director and was present at most of the crucial meetings.[10] The exposed political situation of the firm after 1890 apparently forced complications on the executive hierarchy but did not change it fundamentally.

The corporate statutes were inevitably hazy about the staff that would assist the director and executive committee. The principle of indivisible sovereignty discouraged a priori concern with the delegation of decision making. Nonetheless, the statutes did recognize thirteen "officers" of the firm; eight of them were to supervise bookkeeping departments, and the rest were entitled "engineer" or "assistant engineer" and were to oversee production operations.[11] What is noteworthy is how much the list diverged from the positions that really came to matter. By no means were the officers and the effective managers of the PGC the same. The company operated with a nebulous concept of management. Even as crucial a figure as the superintendent of a factory was not listed as an officer. By contrast, the statutes made provisions for such relative nonentities as "chief of correspondence" or "assistant cashier." Moreover, personnel records never distinguished clearly between mere clerks and managers. The conceptual framework organizing the personnel charts was salary level—above or be-

[9] On the graduates of elite engineering schools heading important French corporations, see André Thépot, "Les Ingénieurs du Corps des Mines, le patronat, et la seconde industrialisation," in Le Patronat de la seconde industrialisation , ed. Maurice Lévy-Leboyer (Paris, 1979), pp. 237-246.

[10] AP, V 8 O , no. 733, deliberations of April 14, 1892. The post of administrateur-délégué had always existed (indeed, it was required by law) but had not been filled until this awkward moment for the PGC. Camus did not move out of the director's residential suite within the corporate headquarters until 1898 (see no. 735, deliberations of August 25, 1898).

[11] Ibid., no. 723, appendix to deliberations of December 26, 1855.

low three thousand francs a year—not level of responsibility n Beginning managers were on the same salary ladder as office clerks; both started at eighteen hundred francs. The only difference was that the managers advanced faster. Even without a clear notion of what "management" could and should be, the PGC did develop an executive corps that served its needs well.

The new gas company quickly assembled a staff of twenty-three people, who were primarily responsible for ordinary operations (table 4). Seventeen of these headed technical departments or divisions and were graduates of state engineering institutes; the rest headed clerical departments. The managers below the director did not simply constitute a mechanism for passing on his orders. In fact, it is possible to apply the classic labels of top, middle, and lower management to the hierarchy—though admittedly the language is entirely anachronistic. Nineteen officers supervised directly the production and distribution of gas. Three others oversaw, evaluated, and perfected the work of those nineteen, so they might be considered middle management. The director and his immediate assistants coordinated the efforts of their subordinates and were chiefly responsible for general policy. These distinctions do need some qualification, but they hold true in a broad sense. Between the founding of the firm and the end of its golden age, the size of the managerial staff nearly doubled, with most of the growth at the lower level. There was hardly any further expansion at any level during the era of adjustment. The crisis through which the PGC passed did not spark a reconsideration of administrative organization, and the reduced pace of growth obviated the need for an expanded executive corps.

What sort of relations prevailed among the different managerial levels? The corporate statutes as well as national traditions would lead one to expect thorough centralization.[13] In theoretical terms, the director made all decisions, even trivial ones. In practice, his oversight did cover many matters of detail, with middle and lower managers merely supplying ad-

[12] For examples of personnel charts, such as they existed within the PGC, see ibid., no. 153, "Cadre du personnel," and no. 162, "Assimilation." Michael Crozier, The Bureaucratic Phenomenon (Chicago, 1964), p. 273, writes of a "lag" in the development of French managerial functions because firms were overcentral-ized and managers gloried in being in control of everything. As we shall see, this stereotype does not quite hold for the PGC.

[13] Octave Gelinier, Le Secret des structures compétitives (Paris, 1968); Crozier, Bureaucratic Phenomenon ; Eugene Burgess, "Management in France," in Management in the Industrial World, ed. Frederick Harbison and Charles Myers (New York, 1959), pp. 207-231; James Laux, "Managerial Structures in France," in The Evolution of International Management Structures , ed. Harold Williamson (Newark, Del., 1975), pp. 95-113.

Table 4. Structure of Management at the PGC | |||

Number | |||

1858 | 1884 | ||

Top Managers | |||

Director | 1 | 1 | |

Assistant director | 0 | 1 | |

Delegated administrator | 0 | 1 | |

Middle Managers | |||

Head of factory division | 1 | 1 | |

Assistant head of factory division | 1 | 1 | |

Head of gas production | 0 | 1 | |

Head of distribution division | 1 | 1 | |

Lower Management | |||

Factory superintendents | 6 | 11 | |

Assistant superintendents | 1 | 10 | |

Head of lighting department | 1 | 1 | |

Head of by-products department | 1 | 1 | |

Head of machinery department | 0 | 1 | |

Head of coal department | 1 | 1 | |

Head of coke department | 0 | 1 | |

Head of construction department | 1 | 1 | |

Head of meter department | 1 | 1 | |

Head of gas lines department | 1 | 1 | |

Assistant head of gas lines department | 1 | 2 | |

Head of accounting department | 1 | 1 | |

Head of workshops | 1 | 1 | |

Head of legal department | 1 | 1 | |

Secretary | 1 | 1 | |

Head of customer accounts department | 1 | 1 | |

Total | 23 | 43 | |

Sources: AP, V 8 O1 , no. 665 (fols 500-514); no. 153. | |||

vice or information. Yet centralization was not comprehensive. The outstanding characteristics of the PGC's authority structure were the dispersal of decision making and the unclear lines of power An uneven pattern of centralization and decentralization quickly evolved. Both principle and pragmatism gave it a peculiar shapelessness that partook of none of the Cartesian clarity the statutes described.

Managers informally expanded their authority into areas that superiors left for them, and the latter did not guard all their powers with a ferocious jealousy. The director reserved for himself the most noble activities,

appointing personnel, allocating rewards and sanctions, and authorizing expenditures. In these areas there was hardly any delegation of authority to relieve top management from involvement even in petty details. It hardly pays to conceive of a middle or lower management in these matters except as a transmission belt for decisions made at the top. Each December the director personally reviewed the records of every clerical worker and decided on annual bonuses and promotion.[14] Heads of departments participated in these decisions only by providing written comments about employees. The chief of the lighting department lacked the right to grant even a simple leave of absence for a clerk in his office. Usurping that power earned the engineer a formal rebuke.[15] Middle management did not select their own assistants or immediate subordinates; the decisions came from above. Only by restricting information available to a busy director or making strong recommendations could division chiefs assemble staffs of their choice.[16] The power to spend was likewise highly centralized. The director ruled on the type of hand towels that would be purchased for the bathrooms of the headquarters. Not until 1872 did factory superintendents gain the right to spend twenty francs without prior approval from above.[17]

By contrast, there soon came to be important spheres into which centralization did not extend. The director was actually quite removed from the daily operations of major departments. He appeared to know little about products and the ways they were manufactured and did not seek to learn about them. The company had no absolutely uniform wage or labor policies. By the 1860s factory superintendents had ceased reporting to the directors on a regular basis. In these circumstances centralization failed, not by default, but rather by conscious design. The director welcomed the benefits of delegated authority, at least in some spheres. Thus, when the opportunity to install telephones connecting the factories to headquarters appeared in 1879, the director vetoed the proposal on the grounds that the new device would undermine the responsibility belonging to his subordi-

[14] The decisions were formalized at one of the last annual sessions of the conseil d'administration and of the comité d'exécution.

[15] AP V 8 O no. 93, notification of January 9, 1869 (fol. 71).

[16] This informal input may explain how division heads were able to have graduates of their own schools appointed under them.

[17] AP V 8 O , no. 1081, ordre de service no. 20; no. 751, "Secrétariat." Heads of departments and divisions were forbidden to correspond directly with suppliers (ordre de service no. 98). Corporate rules made them get the director's approval for all maintenance projects or for any changes on approved projects (ordre de service no. 93).

nates. Not until twenty years later did the PGC install telephone service, and then only because strike threats imposed the need for immediate communication.[18]

However amorphous the patterns of authority, they were not entirely the product of capriciousness on the part of successive directors. There was a logic, though not a consistent one. The centralization of budgetary and personnel decisions was in a sense ideological, reflecting the directors' conception of their sovereignty. Yet their aloofness from nearly all concerns at the factory level probably arose from pragmatic calculations about control over the labor force.[19] Management did not want workers at each of their plants uniting against the company, and the best way to encourage fragmentation was to treat each factory as an autonomous unit. Furthermore, the director wished to strengthen the hand of superintendents over the labor force by granting his managers the status of masters in their own houses. This mixture of principle and practical calculation generated much corporate policy.

Inevitably, the untidy dispersal of authority gave middle and lower managers considerable responsibility.[20] No document explicitly defined their duties. Their functions evolved as a result of experience, shared understandings, and personal initiative. Strategic, tactical, and operational decisions gravitated to executives at each level. All managers had to be active in four areas—daily operations, planning, financial oversight, and research. Even top management supervised or intervened in the details of daily routine. Most of the burdens fell on lower managers, however, and the PGC was probably understaffed at that level. The chief of the by-products department ran by himself an operation that involved revenues of some two million to three million francs and 250 workers.[21] Several superintendents directed plants with nearly a thousand laborers and millions of francs in equipment with the assistance of at most one other engineer.

Since the PGC never centralized planning procedures, every manager had to divert his eyes from current concerns to consider the future. The director depended on department heads to recommend areas of expansion and new markets. The systematic preplanning of new factories was a task

[18] Ibid., no. 680, deliberations of October 31, 1879, and no. 695, deliberations of April 26, 1899. Superintendents sometimes disregarded formal directives from the chief executive. See, for example, no. 90, "Précautions prises au point de rue hy-giènique pour la boisson des ouvriers."

[19] See below, chapters 6 and 8.

[20] The thousands of reports scattered through the archives of the PGC shed light on their functions. Especially rich are cartons 709-719, 746-770.

[21] AP, V 8 O , no. 1060, "Usines-Traitement des goudrons et eaux ammonicales."

born of the industrial revolution, and it imposed a marathon of toil on the engineers. Any large capital improvement project involved corporate managers in inventing, testing, and perfecting equipment. When the PGC renovated its coal-handling machinery, nearly all new devices were designed by its engineers and constructed in its workshop.[22] Moreover, every department chief acquired a thick file of correspondence with inventors, for they continually explored innovations that could be useful to their departments and examined the more promising ones in their laboratories.

Oversight of bookkeeping was an activity managers dared not neglect. It was a duty on which top management insisted more than any other, issuing sharply worded reprimands when necessary. The factory managers filed fifty-six reports each day on expenditures. Scrutinizing the books was required because honesty was a problem within the accounting staff. When an embezzlement scheme in the factory accounting office was exposed in 1873, it hurt the reputation of a plant superintendent, for the director charged him with insufficient supervision.[23]

Apart from the duties imposed by current and future operations, managers undertook individual research and improvement projects. The engineers rarely left existing procedures as they found them; they devoted many of the workdays to tinkering with details of production. Although the PGC employed a consulting expert to oversee research (for many years Henri Regnault, a distinguished scientist and professor at the Collège de France), the endeavors lacked genuine coordination. Managers' projects were usually self-directed and not always intimately related to their immediate responsibilities at the firm. Nonetheless, the results could sometimes prove useful. The assistant chief of the factory division developed a crucial pressure-regulating device; the entire gas industry used the tables on gas flow calculated by the head of the factory division; a chief of the coke department was responsible for a new type of street lamp.[24] The

[22] On the preplanning of factories, see Sidney Pollard, The Genesis of Modem Management (Cambridge, Mass., 1965), p. 262. J. Laverchère, Manutention mécanique du charbon et du coke dans les usines de la Compagnie parisienne du gaz (Paris, 1900), illustrates the work of the engineers in designing and building their own equipment.

[23] AP, V 8 O no. 161, "Etat des pièces. . ."; no. 675, deliberations of April 24, 1872; no. 676, deliberations of May 3, 1873, and January 17, 1874; Rapport, March 28, 1874, pp. 39-41.

[24] Bulletin de l'Association amicale des anciens élèves de l'Ecole Centrale 35 (1903-1904): 232; AP V 8 O , no. 677, deliberations of October 7, 1874; no. 672, deliberations of June 26, 1867; no. 1060, report of October 10, 1859; Philippe Delahaye, L'Eclairage dans la ville et dans la maison (Paris, n.d.), pp. 151-152; Alphonse Salanson, "Ecoulement du gaz en longues conduites," Société technique de l'industrie du gaz en France. Neuvième congrès, 1882, pp. 157-164.

managers' research agendas demonstrated a disinclination to specialize, which was all well and good given their multifarious duties.

The responsibilities assigned to each post and the career paths of the managers did not allow them to concentrate exclusively on a narrow set of technical matters. Engineers commonly moved from one department or division to another in the course of their careers. Eugene de Montserrat began as an assistant factory superintendent after graduating from the Ecole Centrale des Arts et Manufactures; he then became, successively, head of the secretariat, chief of the coke department, and chief of the distribution division. Plant superintendent Leroy had behind him several years in by-products production and in the machine shop. Louis Dhombres became an assistant factory superintendent after finishing the Ecole des Mines, moved to the coal-testing laboratory, and was promoted to the head of the mounted main office.[25] Even when serving in one post, these managers could not confine their purview to engineering questions. They had to deal with personnel problems and marketing matters, among others. The workday for the head of the by-products department might have included drafting a report on the proper way to clean a coal-tar filter and then a memorandum on the sale of ammonium sulfate to farmers in Picardy. The director did not hesitate to ask the chief of the distribution division for advice on legal strategies regarding a gas explosion, and the latter did not hesitate to respond. This engineer also had to make business calculations about which streets would be profitable to service.[26] The analysis of budgets or capital improvement options was an integral part of the managers' duties, as they usually lacked the staff to handle the financial questions for them. Being a part of a large-scale organization—and only a handful of French corporations were larger than the PGC—imposed only a limited degree of specialization on the managers.

Such duties left little room for leisure and obscured the distinction between free time and work. Managers did task-oriented labor, and there were no fixed hours on the job. Factory superintendents and their assistants lived at the work site and were on duty at all times. The director, the head of the factory division, and the chief construction engineer met on Saturday mornings to examine new projects. Sunday labor, at least on

[25] In the absence of personnel dossiers for managers, one must follow their careers through the deliberations of the conseil d'administration , AP, V 8 O , nos. 723 -737.

[26] Ibid., no. 626, "Sulfate d'ammoniaque"; no. 92 (fols. 126-130); no. 828, "Accidents." The head of the secretariat wrote reports on the marketing of coke; see no. 751, report of June 18, 1858.

personal projects, may have been normal. When the owner of the Rossini Theater bestirred himself early one Sunday morning to have gas restored to his establishment, he found the chief of the lighting department at his office. The chief sent the impresario to see the director, who was also at work and assured him that both executives would be on the job all day.[27] As far as can be discerned from the incomplete records, vacations were not part of the annual calendar. Starting in the late 1880s there were some requests for a week's leave during the slow summer season, usually disguised as health-related absences, but these came from a minority of engineers. It was not only for wage earners that management conceived of hard work seven days a week, fifty-two weeks a year, as natural and inevitable.

Beyond constant application the company also demanded a rare combination of moral qualities from its executives. They had to be eager to accept new challenges and grow on the job. The self-confidence to make decisions on matters that were not susceptible to technical analysis was a basic requirement of their work, and it was a virtue they did not seem to lack. But self-confidence had to be tempered by self-effacement when necessary. The company was not especially sensitive to the egos of its executives and assumed their pride was expendable. The director once sent the assistant factory chief, Edouard Servier, to examine an electric pressure regulator that competed with his own invention. The mission was still more delicate in that his competitor had accused Servier of copying. Yet his superior found that Servier had nonetheless carried out the task with "the most perfect impartiality."[28] Clearly the company expected much from its engineer-managers, and these men, as a result of their backgrounds, expected much from themselves.

The Social Composition of Management

Through its early boards of directors the PGC grew under the casual supervision of some of France's most original and innovative entrepreneurs. Among these were the fourteen principle owners, partners, and directors of the gas firms that had fused to form the company. These pioneers of the gas industry in France had not been members of the conservative Orléan-ist business aristocracy that safely dominated the court and banking circles. Some were clearly outsiders who won great wealth despite, or perhaps as a consequence of, breaking rules. Jacques and Vincent Dubochet,

[27] Ibid., no. 766, report of May 4, 1870; no. 1081, ordre de service no. 180.

[28] Ibid., no. 1070, report of September 25, 1861.

owners of the former Parisian Gas Lighting Company, were born in Switzerland (Vevey) and were well known for their republican principles. They had participated in Carbonari conspiracies in their youth and became wealthy patrons of Léon Gambetta during the Government of Moral Order. Gambetta received financial support from the Dubochets for newspapers and campaigns, most notably during the May 16 (1877) crisis. Vincent's death in 1877 was marked by two distinctions: Leading Opportunist republicans were at his funeral, and he died one of the wealthiest men in France, with an estate worth more than thirty-five million francs.[29]

Louis Margueritte, the principle architect behind the merger forming the PGC and the owner of the largest pre-merger firm, was another outsider. Born into a family of well-off Rouennais merchants in 1790, Mar-gueritte developed a serious interest in both industry and theater. He claimed to have written a tragedy that the Comédie-Française produced in 1824. Though he entered the gas industry the very next year, his ties to the arts did not dissolve. In fact, he married one Mademoiselle Minette, a former actress at the Vaudeville Theater. He eventually came to own huge estates outside Paris and died one of the largest landlords in the Seine-et-Oise. His fortune was rumored to be eighty million francs.[30]

Thomas Brunton, another board member and a partner to the merger, was born to English parents in 1793. His father had made a fortune by taking British methods of cotton spinning to Normandy. The Revolution ruined the business, and his father went to prison during the Terror. Brunton's status as an alien was reinforced by his habit—inexcusable to some proper-thinking Frenchmen—of calling himself an engineer even though he lacked a diploma from an appropriate French school. The Imperial administration declined to recommend Brunton for the Légion d'honneur because he did not "enjoy much consideration among industrialists."[31]

The pioneers of the gas industry were joined on the board by some of the men most responsible for the French "industrial revolution" of the Second Empire. The largest investors in the PGC were Emile and Isaac Pereire, the "best representatives of Saint-Simonian dynamism in service

[29] I. P. T. Bury, Gambetta and the Making of the Third Republic (London, 1973), pp. 111, 307-308, 414, 441. On Dubochet's wealth, see AP, D Q7 , nos. 12387-12389, 12396. Jean-Marie Mayeur, Les Débuts de la III République (Paris, 1979), p. 50, refers to Dubochet as the "Mécène des républicains."

[30] Archives nationales, F12 5201. On hearsay regarding Margueritte's fortune, see Maurice Charanay, "Le Gaz à Paris," La Revue socialiste 36 (1902): 433.

[31] Archives nationales, F12 5098.

of the Imperial economy" according to Guy Palmade.[32] Though the gas company was less pathbreaking and historically significant than the Pe-reires' Crédit mobilier, one of Europe's first industrial banks, it proved more enduring and profitable. The Pereires brought their circle of business associates and fellow investors to the PGC's board.[33] Hippolyte Biesta, the director of the Comptoir d'escompte and a collaborator of the Pereires in creating the Crédit mobilier, was on the first board. Alexandre Bixio, who served on the board from 1855 to 1865, also sat on the boards of the Credit mobilier, the Railroad of Northern Spain, and the General Transportation Company, all Pereire projects. Emile's son-in-law, Charles Rhoné, was also a board member. These associations emphasized the ties of the PGC to the men who were shaking up the French economy during its most dynamic era and to other pillars of the new corporate capitalism.[34]

The Pereire circle continued to encompass most of the leading nationally connected entrepreneurs on the PGC's board even after the failure of the Credit mobilier (in 1867) and the humbling of the family.[35] In spite of its size and profitability the company never succeeded in forging links to other great names of French capitalism, like Paulin Talabot, Henri Ger-main (of the Crédit lyonnais), Paul-Henri Schneider (of Le Creusot) or the Rothschilds. Only one representative of France's financial aristocray, the Haute Banque, sat on its board—André Dassier.[36] As the significance of the Pereire group faded on the national scene, the PGC's board lost its entrepreneurial luminaries. In 1864 at least thirteen of the twenty board members served on the boards of other large and important corporations.

[32] Guy Palmade, French Capitalism in the Nineteenth Century , trans. Graeme Holmes (London, 1972), p. 130.

[33] On this circle, see Robert Locke, "A Method for Identifying French Corporate Businessmen," French Historical Studies 10 (1977): 261-292, and lean Autin, Les Frères Peteire (Paris, 1984).

[34] Charles-Joseph-Auguste Vitu, Guide financier: Répertoire général des valeurs financières et industrielles (Paris, 1864), lists the boards of directors of large firms. Note that reference works on French entrepreneurs, even important ones, hardly exist.

[35] AP, V 8 O , no. 726, deliberations of April 2, 1868. Emile and Isaac Pereire resigned from the board in April 1868, but members of the younger generation remained.

[36] Pierre Dupont-Ferrier, Le Marché financier de Paris sous le Second Empire (Paris, n.d.), p. 70. David Landes, Bankers and Pashas (Cambridge, Mass., 1958), p. 13, notes that "there was hardly a corporation of any importance [in France]— canal, railroad, or public utility—that did not feature among its founders and on its board the names of one or more of these few firms who formed . . . the Haute Banque." The PGC fit his description, but just barely and not for its entire life.

By 1878 only five of the PGC's administrateurs sat on other boards, and these were largely a legacy of the Pereire connections.[37]

The businessmen who replaced the Pereire group or sat alongside its remaining members were well-off Parisians, grands bourgeois, but not captains of industry or finance. The banker Charles Mussard had an estate worth 690,000 francs at his death; he was neither a Pereire nor a Du-bochet. Jules Doazan, a stockbroker (agent de change ), possessed just under a million francs. Athanase Loubet was an important merchant and a former president of the Parisian Chamber of Commerce, but his fortune of 1.8 million francs did not give him the stature of a department-store magnate.[38] Under the Third Republic the PGC increasingly lost its ties to other great corporate enterprises.

Instead, the PGC recruited to its board ever-larger numbers of distinguished scientists, state officials, and administrators to replace business leaders. The representation of scientific expertise became rather formidable. One of France's leading chemists, Henri Sainte-Claire Deville, joined the board in 1874.[39] Louis Troost, professor of chemistry at the Sorbonne, became president of the corporation and one of the more active hoard members. Eugène Pelouse, an applied chemist, came to the board after developing a widely used condenser for coal-gas production and finding new ways to use by-products.[40] There were also a member of the In-stitut de France and a vice president of the French Geological Society. Whereas these notables were eminently qualified to examine the firm's technical procedures, several of the men who joined them on the board had occupied important positions in state administration. The general inspector of mines, Meugy, came to the board in 1880. A former director of the postal service, Baron, served with him as did two former councillors of state. The stockholders confirmed the trend toward reduced ties with other corporations by placing on the board the retired director of the PGC and the current director.[41]

The shifting profile of the board of directors, from economic movers and shakers to administrators, mirrored the declining vigor and aggressiveness of the PGC's entrepreneurial policies (see chapter 4). Yet we

[37] Vitu, Guide financier ; Alphonse Courtois, Manuel des fonds publics et des sociétés par actions (Paris, 1878).

[38] AP, D Q7 , nos. 12371, 10710, 10714, 12342.

[39] Harry Paul, The Sorcerer's Apprentice: The French Scientist's Image of German Science, 1840-1919 (Gainesville, Fla., 1972), pp. 77-78 ; L. F. Haber, The Chemical Industry during the Nineteenth Century (Oxford, 1958), p. 77.

[40] Archives nationales, F12 5231.

[41] Appointments to the board were announced in the deliberations of the conseil d'administration. In most cases information available on these people was slender.

should not make too much of the parallel. There were more important reasons for the growing caution of the corporation, not the least of which was the approaching end of its charter (giving heavy, new investments less opportunity to pay off). Moreover, patterns of aggressiveness and caution in business policies were not clearly confined to a distinct phase of the firm's life, and it is far from certain that the board had more than a passive impact on decision making.[42] The changing composition of the board may well have reflected wider trends in the French economy rather than changes within the corporation. After all, Paris had ceased to be the center of commercial and financial innovation that it had been during the 1850s. Great names in business were fewer and farther between. The depression of the 1880s hit the economy of France harder and longer than those of other countries. When France resumed vigorous economic growth at the beginning of the new century, the innovative leaders were specialists, like Louis Renault, who confined their activities to one firm.[43] Such figures would not have considered the gas industry as marked for special growth in any case and might have turned to the infant electrical industry. The last boards of the PGC were well suited to the task at hand—finding a technological niche and adapting to new corporate responsibilities as a public service and as a model employer.

<><><><><><><><><><><><>

The central figure and animating force in the PGC was the director. After owner-entrepreneur Vincent Dubochet took the post for its first eighteen months, it went to a salaried manager. The PGC was one of the early firms to initiate a practice that was to become a distinctive mark of French capitalism. It sought its chief executive not among the subordinate officers already in the firm, nor among the heads of comparable firms, but rather in the civil service. After Dubochet the directors of the PGC were all engineers of the Corps des Ponts et Chaussées.

The corps was charged with overseeing and improving the nation's infrastructure, and its engineers were indisputably public servants of high rank. They had diplomas from France's most distinguished and exclusive school, the Ecole Polytechnique. Furthermore, the corps accepted only the polytechniciens who had graduated at the top of their classes. The corps in effect comprised a post-Napoleonic aristocracy. Recruited through rig-

[42] Only two board members had enough of an attachment to the PGC to leave substantial legacies to its personnel. Those members were Germain Hervé, an early entrepreneur in the gas industry, and Raoul-Duval, an engineer-entre-preneur and a polytechnicien.

[43] Maurice Lévy-Leboyer and Francois Bourguignon, L'Economie française au XIX? siècle: Analyse macro-économique (Paris, 1985), pp. 78-84; Palmade, French Capitalism, pp. 187-216.

orously competitive examinations, the engineers who were admitted came overwhelmingly from haut-bourgeois families. The purpose of their long years of preparation and demanding careers was service to the state. Moreover, members were bound by powerful codes of collegial loyalty and personal honor. Wearing the distinctive military uniform at all times was obligatory for the engineers of the corps. The dignity of the corps was an ideal around which the members had to organize their lives. Aristocrats of the Old Regime had had to accept an occasional mésalliance; there was nothing they could have done about the waywardness of individual blue bloods. However, the engineers of the Corps des Ponts et Chaussées had to submit their marriage plans for approval to their director general.[44]

Preparation for the corps marked the engineers for life. Each officer was the product of about fifteen years of cloistering—first nine years at the lycée, then six years at the Ecole Polytechnique and the Ecole des Ponts et Chaussées. The latter two were run on a military model, and minute regulations governed the details of the students' lives. Vacations were short and infrequent; students spent little time outside the school. Hazing and deeply rooted customs inculcated a strong corporate identity.[45] At the same time, the rigors of the selection process and of the training bred a sense of elitism and authority. Contemporaries noted in the officers that emerged from this formative experience a distinctive comportment and even a distinctive way of thinking. No wonder the chief executives of the PGC always identified themselves first as "engineer of bridges and roads" and only then as director of the firm.[46]

The PGC was one of the earliest private enterprises to take engineers out of state service and place them in corporate management. The path by which these post-Napoleonic aristocrats came to accept—even welcome— the new career opportunities is worth examining. Members of the corps enjoyed great prestige; they were admired for their learning, for their expertise, and for the weighty matters they handled. There was hardly a family in France that would not have taken pride in having a member in the corps. The daily existence of an officer, however, was usually mundane. The pay was modest, barely enough to sustain bourgeois standards

[44] On the corps, see E Fichet-Poitrey, Le Corps des Ponts et Chaussées: Du Génie civil à l'aménagement du territoire (Paris, 1982), and A. Brunot and R. Coquand, Le Corps des Ponts et Chaussées (Paris, 1982).

[45] Fichet-Poitrey, Corps, pp. 33-34; John Weiss, "Bridges and Barriers: Narrowing Access and Changing Structure in the French Engineering Profession, 1800-1850," in Professions and the French State , 1700-1900, ed. Gerald Geison (Philadelphia, 1984), pp. 30-40.

[46] Brunot and Coquand, Ponts et Chaussées , p. 133. The directors turned over 5 percent of their salaries to the state for their pensions as engineers "on leave."

unless subsidized by private wealth. The engineers' duties could often be routine or at least subject to bureaucratic roadblocks. It is easy to imagine that there were discontents, and Honoré de Balzac, that preeminent interpreter of the bourgeois soul, left a memorable literary portrait of a troubled engineer in Gérard of Le Curé du village (based perhaps on his own brother-in-law). Gérard emerged from the Ecole Polytechnique with aspirations for a brilliant career and a yearning for la gloire. Instead, his career, though honorable, brought him mainly hard work, routine, and low pay. He came to dread a future consisting of "counting pavement stones for the state" and waiting for a small promotion every few years.[47] Balzac's speculations on the psychology of the state engineer were dramatic, to be sure, but not necessarily accurate. There was little evidence of a crisis of morale within the corps. Balzac surely underestimated the engineers' commitment to hierarchy, discipline, and service to the state.[48] Individual officers may have despaired, but they did so privately. Outwardly the corps projected a sustained attachment to its responsibilities and to its acquired status. Defections from state service were rare. Not until 1851 did the war minister find it necessary to issue a decree regulating permanent leaves of absence, allowing engineers to take outside positions. Even so, officers did not often take advantage of the regulation until the 1880s.[49] The lack of opportunities may have had much to do with the hesitations. The directorship of the small firms characteristic of the early industrial era was not suitable for men of their talent and standing even if the material rewards were attractive. But the emergence of large-scale enterprise—mines, railroads, machinery construction, and utilities—offered them a lucrative alternative that they might accept as appropriate. The appearance of firms like the PGC allowed this administrative elite to reach out and capture new positions entailing considerable economic power.

Dubochet's successor as director, Bridges and Roads Engineer Joseph de Gayffier, may not have married an actress—the corps would never have allowed that—but he was a trailblazer in his own way. De Gayffier was one of the early members of the corps to leave state service and take a position in private industry. In doing so, he helped create a model that

[47] Ibid., pp. 138-141.

[48] Terry Shinn, L'Ecole Polytechnique , 1794-1914 (Paris, 1980), p. 181, on the mentality of the graduates of the institute. For an assessment of the bourgeois "soul" that differs substantially from Balzac's, see Theodore Zeldin, France , 1848-1945, 2 vols. (Oxford, 1973-1977), 1:11-130. Zeldin stresses the limited ambitions of most French bourgeois.

[49] Brunot and Coquand, Ponts et Chaussées, p. 257; Shinn, Ecole Polytechnique, pp. 94, 167.

would eventually become commonplace in French large-scale industry. In 1858 he was still an exception and perhaps had something of Gérard in him. Born to a wealthy Auvergnat family in 1806, Joseph became a student at the Ecole Polytechnique and at the Ecole des Ponts et Chaussées by dint of hard work and uncommon intelligence. When he finished the rigorous training, he began the long, slow climb up the official rungs of the corps. By the age of forty he was still only a second-class engineer earning forty-five hundred francs a year and had already served in the departments of Indre, Somme, Oise, and Côtes-du-Nord. The modest pay and difficult work may have interested de Gayffier in more lucrative endeavors outside the corps. His subsequent employment showed how both the engineers and the corps would have to adapt to new career patterns.[50]

De Gayffier's first attempt to serve private enterprise went smoothly. In 1845 he left the corps briefly to be director of a public-works firm in Portugal and readily received a leave of absence for that purpose; he was back in the corps within two years. The next involvement with a private firm proved more complicated. De Gayffier asked for another leave in 1856 so that he could take a post with the Grand Central Railroad. His superiors at Bridges and Roads were reluctant to grant the request on the grounds that the position involved directing operations that had been subcon-tracted to another firm. The officials insisted that "the reputation of the corps requires that the position of engineers who take leaves from its ranks . . . must be perfectly defined and must present nothing untoward in the eyes of the public." Clearly the corps was trying to set lofty standards for outside employment, whereas de Gayffier sought to extend those limits· He finally worked out an acceptable definition of the post and received the authorized leave. During his employment with the railroad he earned six times as much as the corps would have paid him.[51]

The merging of the Grand Central Railroad with a larger line placed de Gayffier in a new predicament. He lost his position but was no longer willing to return to the corps· He was reprimanded for not reporting to his assigned post when the leave ended. Soon he suffered the further humiliation of being passed over for promotion to first-class engineer. He apparently spent two years in this ambiguous situation before the offer from the PGC arrived. Perhaps an exceptionally disgruntled state engineer was the only sort that private enterprise could attract at that time.

Why board members of the PGC selected de Gayffier to direct the firm

[50] Archives nationales, F14 22331 .

[51] Ibid. See especially Conseil général des Ponts et Chaussées, deliberations of August 7, 1856.

is not clear. His assignments as an engineer had prepared him for work with railroads. He had planned canals, dredged harbors, and supervised the laying of track, but he had no experience whatsoever with the gas industry. Moreover, his reputation within the corps had its blemishes; internal reports described his character as "inconstant" and the quality of his work as "mediocre." Nonetheless, like most of his colleagues at Bridges and Roads, de Gayffier had had experience administering large projects. It is possible that de Gayffier had made important contacts when he worked with the Grand Central Railroad, for that was a Pereire undertaking.[52]

Still working out the terms by which state engineers would serve private enterprise, the directors of the corps did not approve de Gayffier's new post without some clarification. The officials were concerned that this position would associate him too closely with commercial operations, considered beneath the dignity of the corps. They had to receive assurances that de Gayffier's functions would entail the oversight of a large corporation serving a useful public purpose and that baser matters, such as purchasing coal, would be the responsibility of his subordinates. With those assurances de Gayffier was allowed to begin his thirteen-year career with the PGC (1858-1871). Though he was undoubtedly pleased to earn many times the salary of a Bridges and Roads engineer, his status in the corps did not cease to weigh on his mind. Apparently self-conscious about being only a second-class officer, he campaigned for a promotion even as he assumed the directorship of the PGC.[53]

Emile Camus succeeded de Gayffier as director in 1871 and remained at the helm of the firm for the next twenty years. The son of a prosperous notary from Charleville (Ardennes), Emile had entered the Ecole des Ponts et Chaussées after graduating fourteenth in his class from the Ecole Polytechnique. Like his predecessor, he had held several positions in private firms before his employment with the PGC, and none had been in the gas industry. In 1858 he had taken leave from the corps to head a firm that transformed more than three thousand hectares of marshland around Mont-Saint-Michel in Brittany into arable land. This demanding project won high praise for its technical accomplishments. In 1860 Camus was named assistant director of the PGC. How Camus came to the attention of the gas company is not, in this instance, a mystery: he had married a

[52] Ibid., report of prefect to minister of commerce, January 3, 1855; undated fiche from Corps des Ponts et Chaussées.

[53] Ibid., report of March 24, 1859; prefect to minister of commerce, July 30, 1860.

relative of de Gayffier in 1852 and had worked under his direction at the Grand Central Railroad in 1856.[54] In fact, the last director of the PGC, Léon Bertrand (appointed in 1901), was also a relative of Camus and de Gayffier.[55] The company was thus under the control of one "dynasty" for thirty-eight of its fifty years, showing the narrowness of the search for a chief executive officer. De Gayffier's successors also owed him gratitude for helping create the precedent of leaving the corps to serve a profit-making enterprise. Camus did not face questions from his commanders in the corps about the appropriateness of his position; he received a leave of absence as a matter of course.

Stéphane Godot, who became director in 1892 (serving until 1901), was the only one of the PGC's chief officers to have displayed any personal rebelliousness or an inclination to think critically about wider social questions. As a twenty-year-old student at the Ecole Polytechnique he committed an (unknown) offense that resulted in his expulsion. Receiving indulgence from the war minister, he was readmitted but dropped from ninth to twenty-fifth place in the class. Perhaps as a result of the chastising experience, he redoubled his efforts as a student at the Ecole des Ponts et Chaussées and graduated second.[56] The rest of his life was not a model of passive conformity, however. He became interested in the school of thought inspired by Frédéric Le Play and developed a reputation as an industrial paternalist. When the PGC faced a new era of industrial relations in the early 1890s, Camus turned the post of director over to Godot. The union leaders took the change as a conciliatory measure. He resigned in 1901, ostensibly for reasons of health, when a dialogue about industrial reform was no longer necessary.[57]

Godot's successor, Léon Bertrand, showed no such signs of rebelliousness or questioning. He was the son of a professor at the Ecole Polytech-nique who was also an immortal of the Académie française. Léon obtained only enthusiastic praise from teachers and superiors: his character was "excellent," his work habits "irreproachable."[58] In a sense Bertrand marked the completion of an evolution among the PGC's leaders, from nonconforming entrepreneurs to unconventional state engineers to model officers of France's most distinguished technical corps.

Each of these engineer-directors was part of a national elite, not only

[54] Archives nationales, F14 21851 ; F12 5101.

[55] I have been unable to discover the precise relation among all three engineers, but an elegant tomb in the Père-Lachaise cemetery attests to the alliance of their families.

[56] Archives nationales, F14 11481.

[57] See below, chapter 4, on Godot's relation to the gas personnel.

[58] Archives nationales, F12 8516; F14 11520.

as a result of his own membership in the corps but also through family membership.[59] A generation or two earlier, their progenitors had been successful professionals. Camus's father had been a notary, Bertrand's grandfather a physician. The path of further ascent had led through the grandes écoles and from there to high state posts. The directors' family trees contained numerous maîtres de requêtes and auditeurs of the Council of State, judges, and professors. Relatives in banking or business were fewer. Among the last group were those who had also "parachuted" from a state corps into industry. Official documents were always able to categorize the directors' parents as well-off, but huge fortunes were rare. De Gayffier's personal estate of 632,000 francs was probably typical. Though substantial, it was not the wealth of a Dubochet or even of a board member like the banker Dassier, who died with a fortune of more than four million francs. By moving into the PGC, engineer-directors added sizable income to the prestige and power their relatives enjoyed as hauts fonctionnaires .[60] Perhaps the lure of lucre was not so powerful among most of their cob leagues who remained in the corps, or perhaps desirable opportunities were lacking. As we have seen, the PGC kept its search for chief executives within narrow limits.

Was the Corps des Ponts et Chaussées the most appropriate source of leadership for the PGC? It is hard to identify specific qualities and training that made these engineers essential to the firm. Their education, highly abstract and oriented toward mathematics, did not ensure a technical grasp of industrial problems. The most valuable asset they possessed was the ability to deal as equals with the other graduates of the grandes écoles they were likely to meet in the course of doing business. As polytechni-ciens, they could address the prefect or municipal engineer as mon cama-fade and use the informal tu .[61] Such standing was worth something, but the deepest reason that the PGC's board turned to the corps to find its chief executive was no doubt a conventional, uncritical respect for hierarchy. State and society defined these men as the nation's administrative elite.

<><><><><><><><><><><><>

A clear sign that the Ecole Polytechnique and the state's technical corps did not produce men with precisely the necessary preparation to direct gas production was that the PGC recruited the engineers in charge of opera-

[59] Ezra Suleiman, Elites in French Society (Princeton, 1978); John Armstrong, The European Administrative Elite (Princeton, 1973).

[60] AP, D Q7 , 12341 (fols. 56-57); Shinn, Ecole Polytechnique , p. 90.

[61] For an interesting illustration of the right to use informal forms of address as well as of the inevitable contacts made at the Ecole Polytechnique, see Ibid., no. 155, Fontaine to Godot, April 26, 1902.

tional departments from other schools. Heads of divisions, departments, and factories were graduates of the Ecole Centrale des Arts et Manufactures (founded in 1829) or the external classes of the Ecole des Mines.[62] Both of these institutes had assumed the task of training industrial leaders. Though they lacked the supreme prestige of the Ecole Polytechnique, they stood just beneath it. The bourgeois family that placed a son in one of these state schools had reason to be pleased. Industrialists often chose one of these alternatives over the Ecole Polytechnique for their heir if he was serious about continuing in business.[63]

The Ecole Centrale and the external classes of the Ecole des Mines, with their industrial mission, were products of the emerging factory era. So were their graduates. Just as the early directors of the PGC departed from convention by leaving state service and creating a new role for themselves at the helm of large firms, lower managers were creating their own social persona. The PGC was born at the moment when engineer-managers of industrial firms were appearing. Enrollment figures at the two schools attest to the rapid expansion of the milieu (table 5). No more than the PGC's director did the heads of departments or plants build their identity around business administration. Their professional designation was "industrial engineer," a new occupational title that came into common use around the time the PGC was founded. Earlier all who used the title "engineer" had been members of a state corps. The birth of civil or industrial engineering as an established occupational category can perhaps be dated from 1848, when the Society of Civil Engineers was founded.[64] Managers at the PGC

[62] The term "external classes" needs explanation. Technically, the Ecole des Mines was an extension of the Polytechnique. It enrolled two sorts of students. The "student-engineers" were graduates of the Polytechnique, usually top-ranking ones. These students were destined for the Corps des Mines, which, like the Corps des Ponts et Chaussées, was a highly prestigious body of state engineers. The Ecole des Mines also admitted "external" students, men who had generally not attended the Polytechnique and had gained admission through an examination. These students were not eligible for the Corps des Mines and were being trained for industry.

[63] The early history of the Ecole Centrale is well served by John Weiss, The Making of Technological Man: The Social Origins of French Engineering Education (Cambridge, Mass., 1982). See also Louis Guillet, Cent ans de la vie de l'Ecole Centrale des arts et manufactures, 1829-1929 (Paris, 1929). On the Ecole des Mines, see Louis Aguillon, L'Ecole des Mines de Paris: Notice historique (Paris, 1889), and Gabriel Chesneau, Notre école: Histoire de l'Ecole des Mines (Paris, 1932). The external classes of the Ecole des Mines were not at first so exclusive nor so rigorous as classes at the Ecole Centrale but eventually became much more demanding. Not until its later years did the PGC recruit heavily from Mines.

[64] Terry Shinn, "From 'Crops' to 'Profession': The Emergence and Definition of Industrial Engineering in Modern France," in The Organization of Science and Technology in France , 1808-1914, eds. Robert Fox and George Weisz (Cambridge, 1980), pp. 184-210; John Weiss, "Les Changements de structure dans la profession de l'ingénieur en France de 1800 à 1850," in L'Ingénieur dans la société fran-çaise, ed. André Thépot (Paris, 1985), pp. 19-38.

Table 5. Size of Graduating Classes at Schools of Industrial Engineering | |||||

Year | Centrale | Mines (External Class) | Year | Centrale | Mines (External Class) |

1835 | 16 | 3 | 1875 | 151 | 19 |

1840 | 31 | 4 | 1880 | 162 | 15 |

1845 | 48 | 11 | 1885 | 181 | 24 |

1850 | 67 | 15 | 1890 | 203 | 26 |

1855 | 72 | 18 | 1895 | 207 | 33 |

1860 | 116 | 17 | 1900 | 220 | 36 |

1865 | 135 | 25 | 1905 | 221 | — |

1870 | 174 | 17 | |||

Sources: Annuaire de l'association amicale des anciens élèves de l'Ecole Centrale des Arts et Manufactures. 1929 (Paris, 1929); Association amicale des élèves de l'Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Mines. Annuaire. 1900-1901. (Paris, 1901). | |||||

benefited from its growing social acceptability. Already in 1856 Gustave Flaubert was able to have Charles Bovary's assertive mother entertain aspirations that her son would be either a judge or a civil engineer

The sorts of firsts that PGC engineers could achieve were well illustrated by the career of Louis Arson, the chief of the factory division for thirty-eight years and, as such, the principal operational manager Arson graduated from the Ecole Centrale in 1841 with the first diploma awarded in mechanical engineering. One of his early jobs was with a machine-construction firm that made the first French locomotives and the engines for the first transatlantic steamships. He was the first graduate of the Ecole Centrale to sit on its advisory board.[65] Arson and his colleagues at the PGC were members of the generation that helped establish the social persona for France's industrial managers. It was certainly not the case, however, that the first generation imagined itself without governing norms and models. Only by adapting some of the formal structures

[65] Archives nationales, F12 5082; "Discours de Mont-Serrat," Bulletin de l'Association amicale des anciens élèves de l'Ecole Centrale 35 (1903-1904): 98-102. On Arson's private life and family, there is a carton of interesting documents: AP, D E1 , Fonds Lestringuez.

of the traditional professions did industrial managers gain social acceptance.[66]

The distinctive features of the French engineering profession, as it had developed under the tutelage of the state, deeply marked the careers and work culture of the PGC's managers. One manifestation was the reconstruction of the professional hierarchy within the company in the form of closed castes. As we have seen, top managers were graduates of the most exclusive schools, the Ecole Polytechnique and the Ecole des Ponts et Chaussées.[67] Middle and lower managers were recruited from the technical institutes of the next rank, the Ecole Centrale and Ecole des Mines. These graduates were excluded from top management regardless of their record of achievement on the job, but they had their own privileges. They monopolized the administration of divisions, departments, and factories. By contrast, men with diplomas from the least exalted of the engineering institutes, the Ecoles d'Arts et Métiers (gazarts as they were known), were relegated to modest posts. It was not that these schools failed to provide rigorous training and produce capable students; but the social level of recruitment was lower and the prestige less resounding. The officers of the PGC accepted the gazarts mainly for staff positions.[68] Thus the PGC allocated managerial posts on the basis of criteria external to the firm and replicated the hierarchy of the engineering profession.

Notions about the ways managers should do their work came from the engineering profession as well. Managers inevitably looked to the engineers of the state corps to define their responsibilities and work culture.[69] State engineers provided guidance on how a technically trained elite would function within a bureaucratic setting. They inspired ideals of au-thoritativeness, independence, and bureaucratic loyalty. The managers of the PGC, following the officers of the corps, eschewed specialization and readily delved into all aspects of administration, including nontechnical ones. Far from regarding mundane details as beneath them, they wel-

[66] Robert Anderson, "Secondary Education in Mid-Nineteenth-Century France: Some Social Aspects," Past and Present , no. 53 (1971): 125.

[67] The one exception proves the rule. Eugène de Montserrat, a graduate of the Ecole Centrale, was named assistant director in 1901. The PGC was liquidated before he could have moved up to the top post, if indeed that was a genuine possibility for him.

[68] C. R. Day, "The Making of Mechanical Engineers in France: The Ecoles d'Arts et Metiers, 1803-1914," French Historical Studies 10 (1978): 439-460. Not all large corporations relegated the gazarts to minor posts. See Claude Beaud, "Les Ingénieurs du Creusot à travers quelques destins du milieu du XIX? siècle au milieu du XX?," in Thepot, L'Ingénieur, pp. 51-59.

[69] On the functioning of the engineers of the corps, see Jean-Claude Thoenig, L'Ere des technocrats: Le Cas des Ponts et Chaussées (Paris, 1973), pp. 165-214.

comed involvement in every aspect of supervision. Yet even when they were directly involved in decision making, they posed as impersonal authorities who could evaluate a matter with detachment. The PGC's managers also emulated the state engineers by asserting a degree of independence from their immediate employer and identifying with a larger scientific community. They did so chiefly through their personal research projects, which were related only tangentially to their current position in the enterprise. The factory superintendent, Paul Biju-Duval, and the chief of gas production, Albert Euchène, published findings on the specific heat of iron and nickel. The assistant factory head, Edouard Servier, studied the chemistry of coal tar and made noteworthy empirical observations. His superior, Arson, turned out a steady stream of gadgets from his laboratory.[70] Though there was a good deal of tinkering and research in progress, it was not usually coordinated or directed by the firm toward established goals. The projects reflected the personal interests of the managers, and they considered the materials, laboratories, and personnel of the company at their disposal to pursue their work. The company accepted such independence and even expressed pride in the accomplishments of its engineers when they won scholarly recognition. The only limit it sought to place on the independence of its personnel was prohibiting paid consultation for other firms.[71]

Though there was this independent aspect to the managers' work culture, the impact of the French engineering tradition was to reinforce loyalties to the organization. Nurtured under the aegis of a powerful state while capitalism was still a weak motor of change, French engineers hardly had a chance to form an autonomous professional group with individual careers as the focus of professional life. Instead, state engineers imparted a sense of comfort with bureaucratic procedures, lifelong commitments to the organization, and ambiguity about the morality of the marketplace.[72] The acceptance of hard work and modest rewards coupled with a respect for hierarchical authority that characterized the corps d'état certainly influenced the managers of the PGC. Thus, entitling themselves civil engineers was not a superficial affectation: they were making a statement about their cast of mind and their expectations on the job.

By the late nineteenth century some contemporaries viewed it as a pe-

[70] Bulletin de l'Association amicale des anciens élèves de l'Ecole Centrale 35 (1903-1904): 232; AP, V 8 O , no. 677, deliberations of October 7, 1874; no. 672, deliberations of June 26, 1867; no. 1060, report of October 10, 1859.

[71] AP, V 8 O , no. 666, deliberations of June 26, 1858.

[72] This analysis follows the thinking of sociologist Dietrich Rueschemeyer, Power and the Division of Labor (Stanford, 1986), pp. 122-124.

culiarity of French industry that engineers so dominated managerial posts in private enterprise. Though the monopoly of the profession was especially complete in France, the situation was not unique.[73] In any case, as France's industrial prowess retreated before that of its neighbors, the dominance of engineers became a source of regret and anticipated reform. Industrial critics denigrated the training that French engineers received. The attacks began with the fossilized education at the apex, the Ecole Polytech-nique, on the grounds that its instruction was too mathematical, too theoretical, and contemptuous of the practical problems posed by industry. The PGC, like most firms, implicitly accepted such criticisms, for it drew its personnel from schools that were more specifically oriented toward the application of science. However, observers familiar with German technical training argued that the Ecole des Ponts et Chaussées, the Ecole Centrale, and the Ecole des Mines ultimately resembled the Ecole Polytechnique more than the German schools. All of the French institutes placed far too much emphasis on theoretical approaches and mathematical training; all relied heavily on lectures even though laboratory exercises were necessary for good instruction in the rising fields of organic chemistry and electricity; all led French engineers to develop general knowledge and eschew the specialization that would have been more beneficial to industry.[74] The critics made some worthy points, but they postulated for the engineers a narrow, technical role in production. The responsibilities that managers held in a firm like the PGC did not justify the sort of specialization and laboratory training that the critics desired. Indeed, the partial concentration that French technical institutes did permit often proved superfluous because the graduates' assignments were unrelated to their academic specialties. The ideal of the elite schools, theoretical training aimed at rapid assimilation of new concepts, was not as outmoded as the critics maintained.

[73] Max Leclerc, La Formation des ingénieurs à l'étranger et en France (Paris, 1917). The dominance of engineers in France was not as unusual as Leclerc believed. See Heinz Hartmann, Authority and Organization in German Management (Princeton, 1959), p. 162; Jürgen Kocka, "Entrepreneurs and Managers in German Industry," Cambridge Economic History of Europe (Cambridge, 1978), 7(1):492-589; Chandler, Visible Hand, p. 95.

[74] Louis Bergeron, Les Capitalistes en France (1780-1914) (Paris, 1978), p. 70; Leclerc, Formation des ingénieurs; André Pelletan, "Les Ecoles techniques alle-mandes," Revue de métallurgie 3 (1906): 589-620; Antoine Prost, Histoire de l'enseignement en France, 1800-1967 (Paris, 1968), p. 303. The presumed deficiencies of French engineering education have been summed up and forcefully reasserted in Robert Locke, The End of Practical Man: Entrepreneurship and Higher Education in Germany, France, and Great Britain , 1880-1940 (Greenwich, Conn., 1984).

It is no wonder that the Ecole Centrale was proud of the versatility of its students.[75] Generalized training for careers modeled on the state engineers was what managers wanted and needed.

A more pertinent criticism came in the early twentieth century from Henri Fayol, the founder of managerial science in France and one of the most respected engineers of his day.[76] Fayol readily acknowledged the multiplicity of disciplines that managers had to master. For him, the deficiency in training arose from its exclusively technical character. Though engineers faced responsibilities for personnel, marketing, accounting, and financing, they received no formal instruction whatsoever in administration. Fayol refused to regard a capacity for mathematical reasoning as a sound basis for judgment in these areas. For decisions in these nontechn-ical fields the PGC followed the British model of empirical training on the job. Perhaps Fayol underestimated another quality that French technical training succeeded in imparting, a sense of confidence in handling the disparate responsibilities of business management. The engineer-managers of the PGC appeared comfortable with their multiple duties: their decisions may not have been especially keen, but they were consistent and conscientious. Such comfort with nontechnical fields may explain why the engineering profession ignored Fayol's challenge for so long.

The influence of the state institutes extended to staffing. In countries like Britain, where such institutes did not exist, filling managerial positions was a great problem. Owners refused to trust salaried executives to use their capital honestly and efficiently, so kinship and friendship played a large role in hiring.[77] The engineering schools of France provided the guarantees of probity and expertise that personal familiarity did across the Channel. The PGC relied on the recommendations of the school directors more than any other source of recruitment. Faith in the excellence of the alma mater, reassurances provided by shared experiences, and established contacts made managers draw their new colleagues from their own schools. Factory chief Arson recommended one engineer after another from the Ecole Centrale. As his influence waned and Paul Gigot, his assistant, took charge, appointments gravitated to the Ecole des Mines, Gigot's alma mater.

More than excellence of training, the engineering institutes offered the

[75] Weiss, Making of Technological Man , p. 225.

[76] General and Industrial Management , trans. Constance Storrs (London, 1949). Fayol first published his influential tract in 1916, but it was based on talks given before the war.

[77] Pollard, Genesis of Modern Management , pp. 11-13.

PGC a cadre of managers with the proper attitudes and firm character. Despite minor variations in curriculum, all the institutes sought to impart an ideology of sobriety discipline, and assiduousness. Standards of accomplishment were very high, and the schools worked the students mercilessly. Consciousness of class rank, continuously reassessed, ritualized the view of life as a constant struggle. Any student who did not embrace hard work and persistent application left the program. Those who remained developed a sense of intellectual and moral elitism. For good reason one historian of the Ecole Centrale has labeled it a "factory of the bourgeoisie."[78] Although not all graduates attained the schools' ideals, the PGC found among them a group of men with ample aptitude for science, a passion to apply it, and a commitment to the work ethic. The PGC took full advantage of the discipline inculcated at the Ecole Centrale and Ecole des Mines.

Satisfied with the elite schools and loyal to them, the PGC regarded the Third Republic's efforts to create new institutes of applied technology in the last two decades of the century with complete indifference. The company gave no support whatsoever to the creation of the Ecole de Physique et de Chimie Industrielle when it was founded in Paris in 1882 and hired only a few of its graduates for humble laboratory posts.[79] The firm did not wish to make a place for specialists and technicians lacking elite diplomas in its managerial structure.

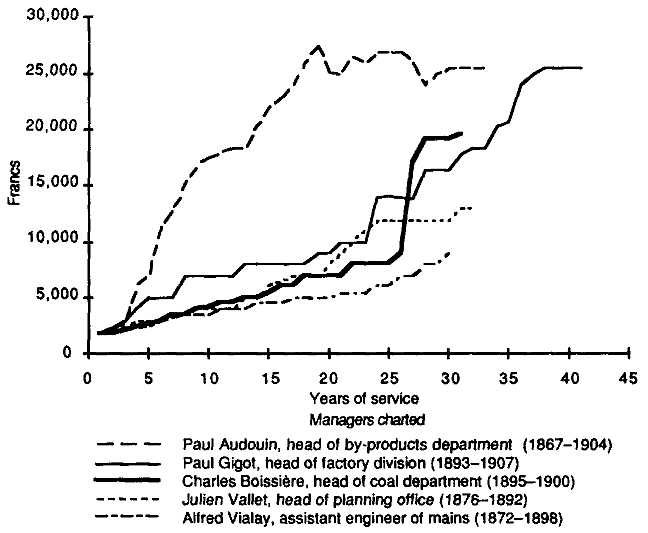

Careers and Rewards

The privileged family background of the young men who received diplomas from the grandes écoles is well documented. Not only the Ecole Po-lytechnique and its schools of application (Mines and Ponts et Chaussées) but also the Ecole Centrale and the external classes of the Ecole des Mines were preserves of the well-to-do bourgeoisie.[80] The social antecedents of the PGC managers who were centraux conform to the rule. Their fathers

[78] Weiss, Making of Technological Man , p. 234; Weiss, "Bridges and Barriers," pp. 39-41.

[79] Ville de Paris, Cinquantième anniversaire de la fondation de l'Ecole de physique et de chimie industrielle de la ville de Paris (Paris, 1932). On another set of new technical schools, see Harry Paul, "Apollo Courts the Vulcans: The Applied Science Institutes in Nineteenth-Century French Science Faculties," in Fox and Weisz, Organization of Science, pp. 155-181.

[80] Maurice Lévy-Leboyer, "Innovation and Business Strategies in Nineteenth-and Twentieth-Century France," in Enterprise and Entrepreneurs in Nineteenth-and Twentieth-Century France, ed. Edward Carter, et al. (Baltimore, 1976), p. 108; Weiss, Making of Technological Man, p. 205; Shinn, Ecole Polytechnique , pp. 101,142.

Table 6. Family Background of Engineers from Ecole Centrale | |||

Alumni at PGC | |||

Fathers | All Graduates 1830-1900 (%) | No. | % |

High Income | |||

Property Owner | 31.8 | 14 | 53.8 |

Businessman | 34.6 | 5 | 19.2 |

Professional | 12.7 | 6 | 23.2 |

Low Income | |||

Employee | 10.9 | 1 | 3.8 |

Artisan | 5.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

Farmer | 4.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

Total | 100 | 26 | 100 |

Sources: Archives de l'Ecole Centtale, Registres de promotion; Maurice LévyLeboyer, "Innovation and Business Strategies in Nineteenth- and Twentieth Century France," Enterprise and Entrepreneurs in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century France, ed. Edward Carter, Robert Forster, and Joseph Moody (Baltimore, 1976), p. 108. | |||