16

A Few Pounds of Lit Crit

The angry professor asked: "Why do you publish only books about Ezra Pound in American literature?" This accusation of prejudice, more than the one about poetry in English, took me by surprise. I mentioned the huge Mark Twain series and books about Melville and Wharton by colleagues of the accuser. But the Twain, he said, was an editing project and the others were only two and were published quite some while before.[1] I could have mentioned, but did not, that my own personal taste happened to be more Proustian than Poundian—pure American that I am and, like Pound, born in the state of Idaho. Nor did I think to point out that we had no special reason to favor an author who once wrote: "Piracy is lesser sin than the continued blithering of University presses, the whole foetid lot of'em, men with NO human curiosity, gorillas, primitive congeries of protoplasmic cells without conning towers, without nervous organisms more developed than that of amoebas."[2]

We had never consciously thought to put together a list in American literature, or in English literature for that matter. Other areas had to be worked at, we thought, whereas there would always be submis-

[1] Leon Howard, Herman Melville: A Biography (1951), and Blake Nevius, Edith Wharton: A Study of Her Fiction (1953).

[2] In Guide to Kulchur (London, 1938), 147. Pound was writing about the lack of bilingual editions of Chinese classics and noted that one edition may have been pirated.

sions from the large English departments, and all we needed do was to choose the better ones. Not entirely true, I can see now, looking back, but enough true to make some practical sense of our attitude. And in literature, as in other fields, one thing leads to another, one book brings in other books. So if we then had a group of books on Pound, it was largely because we had published the first one in 1955.

Our critic had, unknown to me, submitted a manuscript that got unfavorable readings and was declined—perhaps a mistake on our part, because he was quite intelligent. Thereafter we became better acquainted; he came on the Editorial Committee and saw how we worked, saw that we were publishers, hence generalists, and that personal preferences played little part in fashioning the book list. Over the years, and in one way or another, we managed to make friends of several who came to us as enemies. A term on the Editorial Committee could be hugely enlightening.

Our first Pound book was written by John Espey, another UCLA colleague of the critic. Entitled Ezra Pound's Mauberley: A Study in Composition, it surprised both author and publisher by attracting much critical attention. It later went into paperback and is still in print. The author, wrote one reviewer, "amasses a whole album of new perceptions and . . . new validations."

One thing led to another, and from that point on it is easy to see connections. By the time the next manuscript came in, Espey was on the Editorial Committee and he made so many useful suggestions to the authors that they asked us to put his name on the title page as third author. An Annotated Index to the Cantos of Ezra Pound, by John Edwards and William Vasse, came out in 1957, perhaps the first reference book to that difficult poem.[3] If we had known then how Pound studies would grow and flourish, we might have set the book in type instead of reproducing it from typewritten copy, after inserting Greek and Chinese characters by hand. And it was surely the existence of this WPA project—as Pound is said to have called the book—that

[3] About this same time Edwards, then on the Berkeley faculty, brought the manuscript of Mary Barnard's Sappho to us.

several years later led K. K. Ruthven to send us from the University of Canterbury in New Zealand the manuscript of his A Guide to Ezra Pound's Personae (1926), published in 1969.

The book that seems to have put the stamp on us as Poundian publishers came out in 1971 and was described later by a hostile critic as "the Bible" of the Pound industry. Although a bible may seem more suitable to a cult than to an industry, the critic—if I have it right, and the article is not at hand—was firing a broad salvo at the host of scholars, here and abroad, who by then were working on Pound and his Cantos . Literary "industries"—Joyce industry, Twain industry, and others—are apt to spring up when an author's works are voluminous, complex, and obscure enough to provide endless material for study and disagreement.[4]

And when the author himself is complex and contradictory—when he is kind and generous to friends and others, helping unknown and distant writers like Mary Barnard, but writes viciously of those who cross him, when he remains very American but broadcasts treasonable hate against his country, when he espouses weird economic theories and yet provides the clear intelligence that guides the rebirth of poetry in our century—when he is all of these things and more, then there are apt to be as many detractors as disciples. Liberal critics, like the one mentioned above, are often unable to separate poetics from politics. And even without the corruption of politics, many of us appear unable to deal with public figures who are not all of one piece. Thus, and in regard to another matter, one of our editors, brilliant but sometimes stubborn, once condemned the introduction to a book, calling the famous writer (not Pound) a charlatan. To which I could only reply: "Yes, but what you are forgetting, Grant, is that one can be a charlatan and a genius at the same time." The contradictions in Pound have led to violent words among the intellectuals, such as those thrown about when The Pisan Cantos were awarded the Bollingen prize by the Library of Congress in 1949. By now, one hopes, the past has retreated, the rage is mostly dissipated, and it is possible to

[4] The Mark Twain case is rather different, as we have seen in another chapter.

deal sympathetically with a great but flawed man. A few could do so twenty years ago.

One day Hugh Kenner, recently come on to the Editorial Committee, sent me an issue of a little magazine, containing his article "The Invention of China." He could not have known that Cathay —especially "The River Merchant's Wife" but also the other poems in that small volume—happened to be the work of Pound that most appealed to me. I was then too lazy, or too involved in other things, to have read my way through the Cantos —something I might have told the accuser mentioned above—but had been struck by some of the shorter poems. Presumably Kenner sent the article as a courtesy, but I swallowed as if it had been bait, wrote back my pleasure, and asked whether the piece might be part of a book and, if so, could we publish for him. Yes, it was a book, said he, but was contracted to an eastern publisher, who had given a royalty advance—but now seemed unenthusiastic. So the ball was in my court, and I offered to double the advance, so that he could buy his way out of the contract and have something left over for wine or computer ware. Not a usual university-press practice but justified this time, I thought.

As The Pound Era begins—in Jamesean and unacademic prose—it is June 1914 and Henry James is strolling down a street in Chelsea with his niece, and there they run into Ezra Pound and his wife Dorothy Shakespear. From then on this long book is a mixture of literary and personal history, literary and social criticism, explication of key verses, evocation of people and places. Altogether perhaps a recreation of a temps perdu, a gone world, not very long gone but quite unlike our present world, a literary age, with Ezra Pound at the center, others revolving around him—James, Ford, Eliot, Lewis, Moore, Williams, and even Joyce. Literary criticism become literature, a rare thing.

Because of this book, and others that were coming in or being offered by London publishers—one thing leads to another—I went to the Pound conference at the University of Maine in 1975, a mixed gathering of scholars and disciples, presided over by the eminent entrepreneur of Orono, ringmaster of Poundian affairs, editor of Pai-

deuma, Carroll F. Terrell. I was rather out of place, knowing less about Pound than anyone present, nodding blankly at mention of Malatesta or Omar or Brunnenburg. I did know something about Montségur, the little mountain in Provence where Pound once went in his pursuit of the troubadour lyric, but no one spoke of it. I gave a short talk about publishing and, with the help of Kenner, signed up a few projects for the Press. Terry himself, from his central position in the great web of Pound studies, undertook to compile a new guide to the Cantos, replacing the now outdated Annotated Index . It was eventually published in two volumes.[5] And at Orono I met Louis Zukovsky, poet and friend of Pound, and arranged to publish for the first time in one volume his long poem "A." Original poetry but not new and unknown, the culmination of a life's work. Later the Press published the collected poems of Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, and others.

Why we went to Montségur, Bob Zachary and I, is no longer clear to me. I seldom go on literary or other pilgrimages, having made a few and come away empty-handed. Driving near Chartres one day a few years earlier, I saw the name Illiers[6] on a road sign and swung the car around. In the town I happened to coincide with a small group being shown through the house of Tante Léonie. And I walked outside the town and along the little river, trying to see the two côtés, or ways. It was all pleasant enough on an autumn afternoon, but no ghosts were there. The simple bedroom must have been like any other of the time. The hawthorns were not so different from hawthorns in Berkeley. In the town there was a bakery shop called Les Madeleines, and I suppose one could have bought some, like a proper tourist, but I did not go in. The little church was not the church of Combray, although it had made its contribution along with others.

I should have known—perhaps I did know—that I would find nothing I had not brought with me. I could not see with the eyes of

[5] Carroll F. Terrell, A Companion to the Cantos of Ezra Pound (1980–84).

[6] Now renamed Illiers-Combray, I believe.

On the way to Montségur. Zachary at Cahors.

a child a hundred years before, or with the inner eye of the man that child became and whose words could make the reader see. The clef to a roman of second or third level—New York intellectuals writing about each other—may be useful or at least curious, but the key to a great novel is not so easily come by. What the great writer adds to the model or to the skeleton is virtually everything. It was Proust himself, as I have noted before, who wrote that the work of art is made not by the quotidian self but by a secret or inner self that may have little or no connection with the artist's daily life. So much for most literary biography.

But Montségur is not Combray, is a historical rather than a literary site, with the history made a little more attractive by Pound's interest. Still, why did we go? We happened to be driving in France; Kenner must have mentioned Montségur as a place to go, or we remembered it from The Pound Era; I had read Zoé Oldenbourg's great historical novel The Corner-Stone (La pierre angulaire) , with its vivid

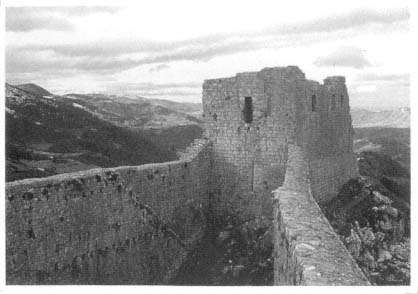

Montségur.

scenes of the Albigensian Crusade, the bloody religious wars in which the northern French put down the southern French in the thirteenth century. And eventually drove out the southern French language, Langue d'oc or Provençal, the tongue in which the troubadours wrote their lyric poetry, so important to Dante and much later to Ezra Pound in his search for the source of lyricism in the West.

In southern France one goes to Foix and then south and east toward the Pyrénées. At the top of a pass on local highway D9 one parks and climbs a steep rocky trail, called a sentier pénible by the green Michelin, to the roofless stone temple at the top of the mountain. Here in 1244 some two hundred Albigensians—heretics to the great church—were besieged and eventually burned on the plain below.

Pound went there in 1919 with his wife Dorothy, and Kenner followed while writing The Pound Era, as his photographs in the book show (pages 333–34). Both had the good sense to go in the summer; Zachary and I arrived in late January. More knowledgeable than I about Pound and other matters, Bob the indoorsman was less

at home on the mountainside. I remember that the upward scramble almost did him in. As we sat on the stone remains at the top, the coldest wind I have ever felt came down off the Pyrénées above. My tired and freezing companion suggested that the Albigensians had surrendered not from hunger or military weakness but because burning at the stake would provide a few moments of warmth. That burning was almost the end of the Albigensian heresy. Provençal poetry died about the same time.

Only a fraction of our books of lit crit, and lit hist and lit ref, were about Ezra Pound or even about modernist literature. Others ran into the hundreds, but none, from Malory and Chaucer down to the present, grouped themselves in quite the same way or came with such personal overtones, and none caused us to scramble up even small mountains. Over the years and without pain or complaint we put together a large clutch of books about that other hero of modernism, James Joyce, including three lexicons to the Gaelic, the German, and the classical words in Finnegans Wake . In 1966 Kenneth Burke, once called by W. H. Auden "the most brilliant and suggestive critic now writing in America," spent a term as Regents Professor on the Santa Barbara campus, and again one thing led to another. Zachary became Burke's personal editor, and after a few years the Press had in print almost the complete writings of Burke, critical, philosophical, and imaginative. None of them ever sold very well, I believe, but they added luster and substance to the list.