Chapter VII

Obviation and Myth

The Dialectic of Foi Social Process

Throughout the last four chapters, I have assumed (with considerable anthropological precedent) that a basic orientation exists among the symbolic usages of any people and that this orientation is a function of the workings of the symbols themselves. The function can be simply stated: the conventional usages define, in and of themselves, what we would call (in semiotic rather than sociological terms) the moral or collective realm. As opposed to conventional usages, there are others whose construction impinges upon these semantic (or syntagmatic) domains. Although the meaningful properties of conventional usages require that they be treated as metaphors in some sense, I shall go on to assume that nonconventional usages may be treated as a cultural order in contradistinction to the conventional. This self-structuring orientation that I am assuming thus replicates Geertz' notion of a dialectic between "ethical" and cosmological ("worldview") realms such that each "emerges" from the other (1973). Dumont's (1965) discussion of the individual versus the collective suggests, furthermore, that the nonconventional can be opposed to the conventional as a differentiating function. Marshall Sahlins (1979) has similarly argued that individual experience and cultural meaning are mutually constitutive, describing them as respectively encompassing referential (semantic) and metaphoric signification.

Given this opposition, the question arises of the relation between the two realms, which becomes the relation between conventional (that is, literal, nonmetaphoric) and nonconventional (metaphoric) usages. I have defined the Foi realm of conventional usages as consisting of a set of images that depicts a flow of vital and personal energies and forces. Symbolically opposed to this domain are the idioms of human action and intention. For the Foi, this domain comprises the efforts of men and women to halt and redirect such vital forces into morally appropriate channels so as to create the artifice of human sociality. In chapters 3 and 4, for example, having outlined the content of the conventional distinction between male and female realms, I described how this distinction is maintained by the ongoing attempts of men to control sorcery material and to ward off illness. In chapter 61 observed that the Foi geographical environment of place names is recreated in a socially relevant form through the innovative medium of mourning songs.

As I noted, the metaphoric quality of these processes rests on the fact that they involve the substitution of one kind of symbolization by another. But I have also emphasized that what we might label as Foi kinship is defined not by genealogical criteria but by the bridewealth networks a person participates in. And since the exchange of wealth items that forms such networks is also a matter of substitution—of wealth objects for human vitality and continuity—then the processes of Foi social structure should also be susceptible to this kind of tropic analysis. I therefore now wish to analyze the sequences of the Foi marriage and mortuary cycles, described in chapter 5 as the progressive alternation between what for the Foi are innate conventional distinctions and the opposed social processes that serve to maintain such conventional orders.

All major social process for the Foi begins with the conventional separation between men and women, or between male and female domains. In figure 6, I label this as the starting point A of a dialectical alternation I now describe. The daily life of the Foi represented in one of its most important aspects the intersection of male and female productivity, as I suggested in chapter 3. When bridewealth items are given, however, the focus is shifted from this general distinction between the sexes to a more specific one between wife-givers and wife-takers. The initial negotiations of betrothal and bridewealth are the affair of the immediate kinsmen of the bride and groom so that at this stage, the distinction between wife-givers and wife-takers is one

Figure 6.

Tropic Alternation in Foi Secular Marriage Sequence

between individuals rather than larger social units such as the local clan or lineage. Since affinity and its attendant behavioral restrictions begin with the acceptance of the betrothal payment, it is the transfer of wealth that creates the affinal alliance. I will label the giving of the betrothal and bridewealth payment as B in figure 6, and the resulting affinal distinction between wife-givers and wife-takers as C .

In terms of my argument, it is necessary to view these two distinctions as analogous. In the bridewealth transfer, the wife-takers give male items of wealth and wife-givers provide the bride and her attendant gifts of female domestic implements and clothing (the arera gifts). The two parties to a marriage thus represent themselves as provisioners of male and female products, in a manner similar to which men and women provide each other with specific sex-linked foodstuffs on a more regular basis. Though the two kinds of transfer are differentially contextualized, they are analogues of each other at the level of cultural analysis with which I am concerned. I have thus drawn a line between A and C in figure 6 to show that, in the act of transferring bridewealth, the conventional distinction between the sexes has been temporarily supplanted or substituted by that between affines, and that the two therefore become metaphors of each other.

I identify the next stage in the sequence, which I have labeled D , as the final transfer of the buruga nami , the bridewealth pigs that the wife-takers give upon the birth of the bride's first child. Since the Foi say that a person is equally the child of both his father and his mother's brother—in other words, since he is related consanguineously to both his father's and his mother's group—the conventional distinction between affines has become correspondingly ambiguous. Thus, although the buruga nami is part of the bridewealth, the Foi say that it is given only when the first child is born. In other words, the buruga nami is given by a "child-taker" to a "child-giver," thus once more shifting the meaning of the conventional distinction between affines. The men formerly related as wife-takers and wife-givers are now additionally related transitively through the child they both consider their own. The payments that pass from wife-taker to wife-giver at this point become matrilateral payments, given to ensure the health of the child by mitigating the spiritual illness that can be sent by the child's mother's brother. These payments are made by the sister's husband to the wife's brother but are called "payments to the mother's brother." I label this stage in the sequence E . The line I draw between E and C depicts the symbolic transformation of affinity into its analogue, matrilaterality.

As I described in chapter 5, a man who feels he did not receive enough bridewealth for his sister can become the unwitting agent of the matrilateral sickness that attacks his sister's child in such cases. Under the same reasoning, a man can also demand pay from his father's sister's son (FZS), especially upon the marriage of the latter's sister. A man and his cross-cousin thus may initiate ka'o manahabora exchanges of (female) foodstuffs and (male) wealth items in order to reimpose the original affinal interdict that existed between their fathers, who were brothers-in-law to each other. As I have already noted, the Foi say that cross-cousins are "like brothers," but unlike brothers they belong to different clans, and unlike brothers one's mother's brother's son (MBS) has the ability to send illness to his FZS if he is dissatisfied with the bridewealth he received for the latter's sisters. Yet because they are like brothers—in other words, because their parents were siblings—cross-cousins call each other's spouses by the same terms they call their siblings' spouses. The relationship between cross-cousins thus combines both consanguinity and affinity: their parents are cross-sex siblings, but they are also brothers-in-law. In the cross-cousin relationship, the original interdict that separated male and female and wife-giver and wife-taker has been dissolved, or combined into one analogue.

The initiation of ka'o manahabora payments that I identify as point F in figure 6 serves to return the sequence to its original distinction between male and female, since the two cross-cousins give male and female items respectively, and since one's cross-cousin can cause kumabo illness, which the Foi classify both etiologically and symptomatically along with women's menstrual illness.

In other words, what began with point A as a clear-cut division between male and female domains becomes, through the successive differentiations that the Foi make in marriage and childbirth, a sum-mating analogue of the normatively opposed principles of bisexuality, affinity, and consanguinity. Indeed, being merely different refractions of a single analogical social differentiation, they are all metaphors of each other. The progressive explication of this analogy can be defined as symbolic obviation. The sequence I have described begins with the literal or conventional separation of men and women and ends by transforming this literal or semantic opposition with a metaphorical one between male cross-cousins, who are figuratively like male and female to each other. In other words, the "symbolic" rather than the "factual" nature of the distinction between male and female has been

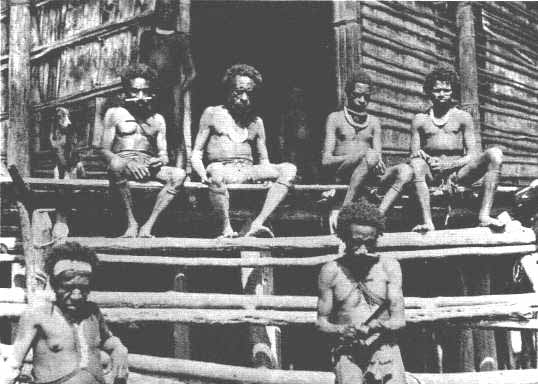

Entrance to longhouse, 1939 (photo by F. E. Williams)

Foi men, 1939 (photo by F. E. Williams)

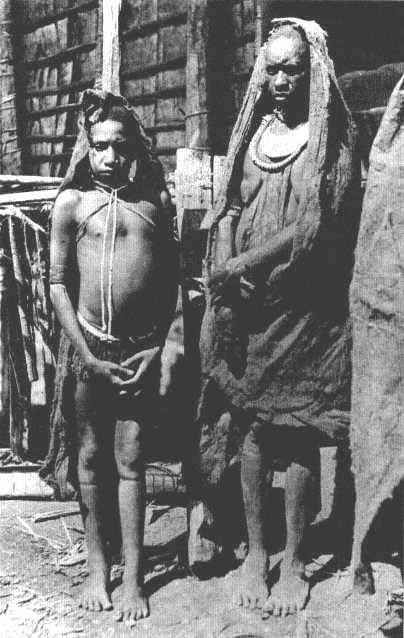

Foi women, 1939 (photo by F. E. Williams)

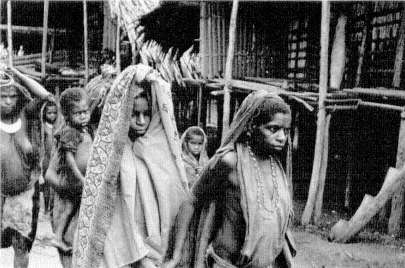

1979: Foi women in ceremonial dress: pearl shells and painted chest cloths (fefa'o kosa'a)

Wa'abu, a head-man of Barutage, displays the

bridewealth received for his daughter, Yebinu

Sumabo of Hegeso leads her co-wife's daughter, Fu, to the house of her

husband-to-be

The transvestite i~ ka of the Usane Habora curing ceremony

Horehabo of Hegeso demonstrates the procedure in constructing a cassowary snare

Canoes along the Faya'a River next to Hegeso longhouse

Heating stones for the earth oven prior to Hegeso's Dawa, December 1984

Baru longhouse, facing the Baru River

Women mourn over the corpse of Iraharabo in the Hegeso longhouse

Men remove the body of Iraharabo, from the Hegeso longhouse surrounded by mourners

rendered apparent or "obvious," for it now encompasses both the relationship between affines and between (certain types of) consanguines.

If obviation concerns the relationship between literal (semantic) and metaphorical usages, then, given the assumptions I have outlined in the beginning of this chapter, it can also be defined as the mutual creation of the conventional (or collectivizing) and nonconventional (or differentiating) cultural realms as I have defined them for the Foi. Referring to figure 6, it can be seen that points A, C , and E represent the transformation of the opposition of male and female into wife-givers and wife-takers, then child-givers and child-takers, and finally back to the analogically intersexual opposition between cross-cousins. Points B, D , and F , by contrast, represent the transfers of wealth that impel the former transformations: betrothal and bridewealth, the buruga nami , and finally ka'o manahabora. B, D , and F therefore represent the imposition of categorical oppositions in Foi social life, while A, C , and E represent the conventional distinctions that result from them. Following Wagner (1978:47-48), I will refer to points A, C , and E as the facilitating (conventional) mode of the sequence, and to points B, D , and F , the tropic constructions that obviate the former, as the motivating (figurative) mode. A more accurate depiction of this tropic alternation would fold the sequence back upon itself so that the obviation of F leads back to the starting point A , as I have illustrated in figure 7. The resulting ternary figure allows one to view schematically the preceding analytic sequence as a series of interlocked triads, ABC , CDE, and EFA . Points A, C , and E are respectively the theses of the triads they initiate and the syntheses of the preceding ones.

However, I now wish to reconsider the significance of point D within this sequence. Recall that unlike the bridewealth pearl shells and cowrie, the buruga nami or bridewealth pigs are shared by all members of the bride's paternal and maternal groups respectively. It must also be noted that unlike shells, pigs have a male and female component, the external flesh and internal organs respectively. This distinction, however, is not given normative expression in the division of the bridewealth pork, since men and women share both kinds of meat without restriction. Therefore, D negates or obviates the original male-female distinction of A , while at the same time the birth of the child it represents serves to render ambiguous the distinction between wife-givers and wife-takers. It is significant in this respect that, unlike the Daribi and many Eastern Highlands groups, the Foi do not artic-

Figure 7.

Obviational Sequence of Foi Marriage Cycle

ulate the contrast between maternal and paternal procreative substances as an idiom of filiative asymmetry.

The obviation of A by D , on the one hand, thus depicts the moral implications of the analogy between the differential provisioning of male and female vegetable staples and the undifferentiated sharing of male and female meat: that maternal and paternal substance relate individuals equally and that the distinction between male and female procreative substances must not be made a model for asymmetrical filiative relations. The relationship between points E and B , on the other hand, extends the implications of this point further, showing that asymmetry in social relations should be confined to the parties to the marriage, and not to the offspring. The obviation of B by E thus depicts the fundamental identity between bridewealth and matrilateral payments that I have already elucidated. Finally, if F is contrasted with C , it can be seen that the end result of the affinal interdict is the paradoxical or analogic brotherhood of cross-cousins: consanguines or "sharers" who are nevertheless impelled by a residual affinity to make ka'o manahabora payments involving the exchange of male and female items. The Foi marriage sequence therefore begins with unrelated wife-givers and wife-takers exchanging male and female objects and ends with consanguines doing the same. Consanguinity and affinity thus become analogues of each other, and it is in this analytic sense that I define obviation.

The second example I describe is the Foi mortuary sequence that I analyzed in chapter 5 and which is in all respects an inversion of the normal Foi marriage cycle. When a man dies, the distinction between the living and the dead is substituted for that between wife-takers and wife-givers (point A in figure 8). The affinal relations existing prior to this death are quickly severed by the death payments made between affines linked by the deceased (B ). This motivates the community to reorient itself in opposition to the ghost (temporarily abrogating the conventional male-female distinction normally characteristic of the community), and all men and women partake of the cooked meat during the Nineteenth Day feast from which the ghost is excluded (C ). Implicitly, as I have shown in the line between C and A , the distinction between the ghost and the living has been substituted for that between men and women. The next step marks the beginning of the return of the community to its normal secular state, as the men and women separate, the men to assume identification with the ghost in the bush and the women staying in the village to care for the corpse (D ). In

Figure 8.

Tropic Alternation in Foi Mortuary Cycle

relation to A, D marks the turning point in the obviation sequence: the reimposition of a male-female dichotomy for the original affinal opposition dissolved by death. It is consistent that the Foi represent this in terms of the essentially sexually bivalent composition of the corpse itself: the male spirit and jawbone and the female corpse or external flesh (which itself constitutes a metaphor of the separate male and female contributions to conception).

Upon their return to the village, the men hold their own feast (E ) from which they exclude the women, emphasizing their identification with the ghost brought about during the Bi'a'a hunting expedition. The men reestablish a total separation of male and female as the means of dispatching the ghost to its proper afterworld; thus E obviates B . Similarly, the death payments severed the previous affinal relationships among the deceased's kin for the same purpose: to separate or isolate the widow. When the feast is over and the men have been successful in ordering the ghost to take up residence in the afterworld, the widow is released from confinement and allowed to view the bones of her dead husband, after which the bones are permanently removed to the burial ossuary. As the community of men and women offered the bones to the ghost in the Nineteenth Day feast urging it to leave the living community, so the men and women now offer the dead man's bones to the widow (F ), forcing her to reassume her place in the society of the living. The sequence began with the disposal of a dead man and ends with the figurative rebirth of a live unmarried woman, and hence the resumption of the normal secular cycle of marriage and bridewealth (see figure 9).

However, it must be noted that if the widow resumes her place among the living, she does so in significantly altered form, for she wears the widow's kaemari mixture and is considered unmarriageable for a period of time due to the jealous interest her dead husband's ghost maintains in her. The kaemari mixture in fact is designed to simulate the offensive odor of a decomposing body: she has become the corpse, so to speak, an image which reveals that the distinctions between the living and the dead and male and female have become collapsed within a unitary ritual expression. Likewise, those affines linked through the dead man now prefix their affinal terms of address with denane , "ghost," so that they are to other normal affines as the dead are to the living. The distinctions between the sexes, between affines, and between the living and the dead have been established as analogues of each other.

Figure 9.

Obviational Sequence of Foi Mortuary Cycle

The Foi sequences of marriage, the creation and obviation of affinity and consanguinity, the recreation of the conventional flow of male and female productivity following death, are all instances of processes that span months or years. However, this should not mask the fact that as a series of successively preemptive metaphors, they are a form of discourse, as I am employing the term. My depiction of them is thus a purposeful condensation of the relevant tropic substitutions and turning points so as to demonstrate the semiotic and discursive foundation of these most important Foi social phenomena. But the tropic creation of the Foi moral universe is by no means limited to these social processes alone. In their stylized and compacted genre, myths provide miniature examples of the effect of metaphoric substitutions. The obviation of social predicaments in myth are prized by the Foi for their humor, irony, or chilling revelation of crucial moral ambiguities.

It cannot be emphasized too strongly that the formal diagrams and the abstract terminology I have been employing are not meant merely to represent reality, as a map depicts a portion of terrain, but to illustrate the relationship between different symbolic functions themselves. I do not consider it necessary to demonstrate a relationship between these diagrams as models and some behavior that they are supposed to explain, simply because I do not think that it is profitable to separate so radically thought and action. I focus the "heart" of this book on myth, and use myth as a model for the rest of social reality, not because I enjoy the arcane exercise of formal analysis but because I feel that myths reveal not only the categorical oppositions of the structuralist enterprise but also what is fundamental to Foi conceptualizations of morality, intention, consequence, agency, and person-hood themselves.

The Ethnography of Foi Myth

It is a common convention in ethnographic reporting that the analysis of myth and/or ritual should follow the analysis of, for example, the social structure, or the kinship, or the economic system of a particular society. This, as Marshall Sahlins notes, reflects the received anthropological definition of culture as a

division into component purposive systems, economy, society, and ideology . . . each composed of distinct kinds of relations and objectives, and

the whole hierarchically arranged according to analytic presuppositions of functional dominance and functional necessity. (1976:211)

As I reach this point in my analysis, however, it is necessary for me to reveal that I analyzed mythology of the Foi before I interpreted the symbolic dimensions of their society. What I have prefaced these remaining chapters with, in other words, is a normative portrait of Foi society based on my structuring in a particular way the images that emerged from my interpretation of their myths. But if I am correct in assuming that the cultural phenomena that constitute our anthropological subject matter are semiotic ones, then the ethnographic facts of Foi society I derive from an analysis of its myths are no less real than, for example, a catalogue of its population size or statistical rates of intermarriage. If I have demonstrated satisfactorily that the most important Foi social events of marriage, exchange, and death can be semiotically analyzed as a series of successive figurative constructions, then, as Sahlins implies, the analysis of myth should provide no less central an arena for the understanding of cultural meanings of such archetypal moral and social images.

In the last chapter I introduced the discursive styles appropriate to myth-telling and observed how the syntax of verb forms the Foi use in mythic narrative facilitates the substitutive structure of the tropic constructions involved. I now wish to describe the Foi practice of myth-telling itself before I analyze the myths as examples of symbolic obviation.

The Foi recognize several classes of folktales and stories. The most common and important ones, and the only ones I am concerned with here, are called tuni . The Foi define most of them as deliberately fanciful and untrue, and they regard as purely imaginary the various giants, ogres, and semihuman men and women—all of whom might be described as "Foi-manqué "—who appear in many of the tuni .

Williams, however, reported that "the Kutubu recognize two general types of story—the tuni and the hetagho " (1977:302). While he describes the function of the tuni as "obviously recreational" (p. 302), the hetagho were understood by the Foi "to deal with ancient events of fundamental importance and consequently possess a religious as well as magical meaning" (p. 303). This contrast corresponds to the one the Daribi draw between "moral tales" and "origin myths" (Wagner 1978:56). It is possible that Williams' rendition of the word hetagho could be what I heard as irika'o —that is what the Foi of Hegeso suggested when I inquired as to the meaning of the hetagho

stories. However, a simpler explanation of Williams' distinction is available.

Occasionally, a Foi man would recite a tuni to me and then approach me some days later and inform me that the particular tuni he narrated had "a base" (ga : the word meaning "base; origin; root; reason; significance" and so forth). What he meant was that he was subsequently informed by other more knowledgeable men that the tuni , in addition to its overt plot, also contained the implicit charter for a kusa or magic spell. The Foi of Hegeso therefore distinguish between two types of tuni : those whose content is limited to their overt moral, and those that also account for the origin of specific magical procedures. These latter myths, I believe, are what the Kutubuans define as hetagho . I found that this category of tuni often included the names of the main protagonists—names that figured significantly in the associated spells—whereas the other category of tuni dealt with unnamed characters.

Of the twenty-four tuni I analyze in chapters 8 through 11, only one is included which accounts for the creation of magical procedures by legendary characters of Foi mythical ancestry. In chapter 4 I noted that Williams observed that the pearl shell origin story he heard at Lake Kutubu (which included knowledge useful in making pearl shell magic) was told to him in great secrecy. It is conceivable that the Foi of Hegeso and neighboring villages avoided telling me those tuni that were associated with their most important magical procedures. On the other hand, I have no evidence that each magic spell known to the Foi has its corresponding myth accounting for its origin. I wish at this point only to explore the implications of the division the Foi make between those tuni that are origin stories for magic spells and those that are not. The implications of such a conceptual division bear upon an understanding of the relation of mythology to a more specific domain of magical efficacy in Foi thought.[1]

From one point of view we can isolate three independent normative institutions: (1) a set of certain subsistence activities; (2) a corpus of magical formulæ; and (3) a corpus of myths, each of which in addition to accounting for the origin of some magic spell also encompasses a commentary on various moral aspects of Foi sociality. By implication, those tuni that describe the origin of magic spells also account for the origin of the activity with which the spell is associated. But let us for argument's sake view these three apparently separate domains as different objectifications of a single symbolic nexus, much as Lévi-Strauss characterized the different properties of a Tlingit cedarwood fish club:

Everything about this implement—which is also a superb work of art—seems m be a matter of structure: its mythical symbolism as well as its practical function. More accurately, the object, its function and its symbolism seem to be inextricably bound up with each other and m form a dosed system. (1966:26)

The corpus of tuni that have associated magic spells or which account for the actions of legendary culture heroes responsible for such spells lends to the Foi economic sphere a moral significance: the resolution of paradoxes within the particular tuni is part of the meaning of the associated subsistence activity, much as the geography of Foi territory created through the media of mourning songs is rendered morally cognizable through the historical actions of human beings. I explore the implications of this relationship between particular myths and magic spells in the course of my analysis of the myths in chapters 8 through 11.

The Foi recite their tuni only during the nighttime after they have finished their evening meal. As they explained to me, they believed that if a person told a tuni during the daytime his anus would close up and he would be unable to defecate. The reciting of tuni , therefore, has an intimate association with the communal sharing of food that the Foi engage during their main evening meal: eating complements speech and vice versa, and speech is in a sense the residue or by-product of a more profound commonality centering on shared eating.

In the man's longhouse, when a man begins to recite a myth, he is immediately surrounded by a group of wide-eyed and attentive children, since it is for the ostensible amusement of the children that the tuni are told. But other adults also gather, most of whom have heard the tales many times before, and it is common for men to interrupt the narrator from time to time to demand a point of clarification or correct an ambiguous phrase.

Although only men recite tuni in the longhouse of course, women and girls gather in the women's houses at the same time in the evening for the same purpose. Four of the myths I present were told to me by women. Most others, although told to me by male informants, were known by both men and women. I attempt to make various contrasts between those myths told by men and those told by women during the course of my analysis.

My own investigation and collection of the tuni interfered somewhat with the Foi conventions of storytelling. Sometimes I tape-recorded the myths as they were told in the longhouse. More com-

monly, men and women visited my house and told one or more myths that I recorded there and then (I must note that they did not seem hesitant to do so during daylight hours, contrary to their belief concerning the harmful effects of diurnal myth-telling). After recording the myth, I transcribed the entire Foi text with the aid of a field assistant and made a word-by-word translation from Foi to English. From this literal translation I recomposed an English version, attempting at all times to preserve the syntactic and stylistic properties of the Foi version within the bounds of comprehensible English.

In addition to the tuni , the Foi also describe another class of stories as dase gahae , literally "first tales." The Foi consider these stories true: they account for real events that supposedly happened in the distant past, though the names of the specific individuals involved have been forgotten. Unlike the tuni , they deal with one basic theme: a malevolent ghost takes the form of a human being and the tale describes the successful attempts of a real human to overcome the ghost. The Foi, especially children, consider these stories particularly frightening, since they portray one of the more abiding fears of the Foi: attack by spirits of the dead.

A significant feature of Foi tuni is paradoxically that which is left unsaid; that which is assumed by the narrator to be understood by the listener. This is partly the result of the fact that much of the action in these tales is normal daily activity that requires little elaboration. For example, a common opening to many plots involves the meeting of a man and woman who consequently "live together." It is not necessary for the narrator to specify that they lived "as a married couple" or whether bridewealth was paid, and so on. This is understood by narrator and listener alike. But this feature is also a deliberate device on the part of the speaker to introduce ambiguity at certain points in the story so that the final resolution is made correspondingly more forceful: a previously veiled part of the plot is more sharply illuminated in this manner. In the above example, it might later be revealed that the man and woman were cohabiting adulterously. The initial ambiguity of the conventional description thus facilitates the particular moral transformation encompassed in the myth.

In a more profound sense, however, the Foi myth teller's failure to elaborate conventional settings only appears as an omission to the anthropologist who himself comes from a tradition that focuses on such settings as the form of moral statements. The Foi, instead, located morality in the particular actions of the characters, judging them not

in relation to a set of transcendent social rules but in terms of the consequences such actions have on relationships between the characters in and of themselves. And as I suggested in the opening chapter, it is the moral quality of such "precipitated" relationships that constitutes the social setting of the myth, but only after the fact, as it were. One might say that, like Indiana Jones, Foi myth makes up its morality as it goes along, and it is this lack of emphasis on moral backgrounding that is singularly evident to the Westerner.

Yet the Foi also go to the opposite extreme and explain in minute detail a minor aspect of the plot that has little to do with the meaning of the final resolution of the story. Much of this is done in a deliberately exaggerated sense to create, for example, a sarcastic, facetious, or ironic setting; to establish the comic or heroic proportions of the characters' personalities; or to deliberately sharpen the conventional roles of those characters.

In recent times, evening sessions of myth-telling must often give way to conversation on the mundane matters relating to all the myriad influences and pressures the Foi have been experiencing as a result of change and development. The Christian Mission too has encouraged the introduction of stories from the Bible, which in the eyes of strong Mission advocates are preferable to irreverent traditional Foi tales. Yet notwithstanding, before the Foi were contacted by the Mission and government, they had pressing concerns with bridewealth and other payments, sorcery accusations and litigations, all of which must have competed with the tuni for attention during the evening period of vigorous discourse. In short, the stories continue to be told and few have been forgotten. The tuni I present here represent only a fraction of the 130 myths I collected during my fieldwork. Most men and women beyond the age of twenty-five are well-versed in many different myths and "first tales." I have selected the ones here as most representative of the corpus. Many are those that were most frequently recounted to me and that the Foi consider important or otherwise favored; others are those I have chosen as exemplifying a single group of nearly identical plots. Yet I also chose them with the aim of presenting the entire range of moral problems to which all the myths are devoted.

Obviation and Structural Analysis

In the first chapter, I asserted that structural and obviational analysis were two sides of the same coin of meaning—one cannot invoke

metaphorical relationships without reference to the signs that are their ultimate building blocks, and one cannot discuss signs without considering the tropic equations that restrict and limit their associations. I also suggested that Lévi-Strauss's approach to myth could be characterized by a focus on sign relationships to the exclusion of tropic ones.

But can one really compare the enterprise of Lévi-Strauss with my current goal that easily? After all, Lévi-Strauss dealt with hundreds of cultures and thousands of myths, spanning two continents, while I have confined myself to the several stories that I collected in the sparsely populated jungle of one small and remote Papuan valley. Yet when all is said and done, the last paragraph of Lévi-Strauss' final volume of Mythologiques seems to reduce his entire magnificent enterprise to the ultimate and simple existential dilemma that humankind faces: how can we become self-conscious? Whether it is three or four lonely Foi myth tellers, or the records of long-dead missionaries attempting to immortalize a dying consciousness, that dilemma is insolubly and irreducibly the meaning of all culture. Semantic and tropic analysis may be formally opposed, as I will show, but they are both essential to the discovery process by which the apparent opacity of myth is revealed as the self-invented inscrutability of the meaning of man's life. Whether one confines oneself to a dozen stories of a single people or the representative corpus of an entire hemisphere, the nature of this insight cannot be made more or less intense. Structural and obviational analysis are not sterile attempts to reduce the artistry of myth to dreary formalisms, but rather joyous and reckless tools with which to demonstrate the overwhelming force that human language—and hence culture itself—possesses.

Let us therefore contrast the semantic and tropic qualities of mythic discourse with the aim not of negating Lévi-Strauss' work, but rather of augmenting it. This is perhaps best illustrated by contrasting the manner in which each analytical mode deals with the problems of variations of a single myth, and fragmented versus whole myths. I therefore begin with a Foi myth that both F. E. Williams and I collected but in significantly different forms. Williams entitled his version "The Origin of the Kutubu People" (1977:313-314 ff.) and rendered it as follows:

A girl was gathering firewood in the bush when she fell in with an ugly old woman. Going on together they came to a haginamo tree and derided to gather berries. The girl climbed into the tree when the old woman, who

stood underneath, suddenly struck the trunk. The tree sprang up to an enormous height, so that the girl could not possibly get down. She sat there crying in the branches and the old woman went away.

For several days the girl remained without food. But one morning she woke to find a great stock of provisions beside her. She ate and ate and fell asleep. Next morning there was fresh supply, and so on each day—sugar-cane, sago, meat, firewood, etc. (a long enumeration). She now stripped bark from the tree and made herself a new skirt and settled down to a solitary life.

Presently she found herself pregnant. She was very puzzled and angry about it. She could not imagine who had brought her to that condition. But in due time the child was born and nursed in the top of the tree; and after that a second child. Now she had a boy and a girl. Food continued to be supplied each day, and ornaments, bari shells, armlets, etc. were sometimes found with it. These she put on her children.

By now they had grown up. The boy had long hair and the girl's breasts were showing. Then one day the mother told her two children to close their eyes together. When they opened them there was no mother, no tree. They were standing on the ground beside a house.

At first they wept for their mother. But there was a supply of sago in the house, so they ate and made themselves comfortable. Then they fashioned a toio [stone axe] and a sago scraper and set about getting their own food. While the girl made sago the boy would hunt. One day they found a number of young plants set down near their house, and they proceeded to make a garden. Another day they found two piglets done up in a parcel of leaves; another day two puppies. The brother said, "You look after the pigs, and I will look after the dogs." He gave them medicines and took them out hunting and caught many animals. Brother and sister were very happy.

But the brother noticed that his sister was each day absent a long time at the sago place. He wondered what she was up to, and followed her secretly. He saw that she used to embrace a palm tree, rubbing up and down against it with her legs astride. Next day, while she was elsewhere, he wedged a sharp piece of flint in the tree trunk, and lay in hiding to see what would happen. When the girl came to embrace the tree again she cut herself, and was thus furnished with a vagina. She fell at the foot of the tree bleeding profusely. The boy did his best to stanch the blood, using various leaves (which have ever since been red or autumn-coloured).a Finally he though of applying bari shells and pearlshells, and the bleeding stopped.

Thenceforward they lived as man and wife and their children inter-married and populated the whole Kutubu district.b

The following were Williams' footnotes to this text:

a In another version it was said that the girl's blood was responsible for red colours in nature, the boy's semen for white colours (white leaves, stones, etc.).

A theory of conception or the make-up of the body, is that the mother's menstrual blood makes all the soft fleshy parts (thus, if you cut yourself the blood flows); the father's semen makes the hard "white" parts—bones, teeth, finger- and toe-nails.

b This story was one of those given me without names for the characters, my informant only supplying them after the tale was told. The mother (i.e. the girl who climbed the tree) was Saube (she became a marua bird on leaving the children). The person who supplied the food, i.e. the father who revealed himself, was Ya Baia, a hawk (the imagery is obvious). The boy was Kanawebe and the girl Karako. These were said to belong to "Paremahugu" amindoba .

The first part of the story is one of the amindoba myths, representing "Paremahugu" as the original clan. The second part, the story of how the girl cut herself, etc., is a general myth. Other versions of it give the characters different names.

Lévi-Strauss, in his analysis of the story of Asdiwal, began by isolating the "various levels on which the myth evolves . . . each one of these levels, together with the symbolism proper to it, being seen as a transformation of an underlying logical structure common to all of them" (1976b :1, author's emphasis); I begin in the same fashion. First, one can observe a succession of separations along a vertical axis represented in the form of a tree: the elder and younger woman are separated by the elder's magical elongation of the hagenamo tree; the mother and her children (a brother and sister) are separated when the two siblings are magically returned to the ground; finally, the sister separates herself from her brother by sliding up and down the palm tree (this point is made clearer in my own version of the myth).

Second, one can note a shift in subsistence activities: from the gathering of firewood and hagenamo berries (a characteristically female activity among the Foi), to the phantom provisioning of male food and other products to the stranded woman in the hagenamo treetop, and to the complementary raising of male and female domestic animals by the brother and sister respectively. This succession of domestic-subsistence regimens is mediated or perhaps paralleled by a series of anthropomorphic birds: first the male hawk husband; second the female marua mother; and last, the banima birds, represented totemically by the first married Foi couple, the transformed cross-sex sibling pair. The first Foi, according to Williams' version of this myth, were thus members of Banimahu'u clan (rendered as "Paremahugu" by Williams). The totemic bird representatives of this clan, the ya banima , was described by my informants as "always dwelling on the ground

and never flying among the treetops."[2] This characteristic of the banima bird becomes significant when I consider my own version of the myth.

Finally, to return to the significance of the vertical axis in more detail, one can note that movement up the tree in each case is associated with the creation of a marriage: first between the hawk man and stranded younger woman in the hagenamo tree, and second between the sister who, by returning to "tree climbing," provides her brother with the opportunity to transform her from a sister into a wife. In figure 10 I have diagrammed what I have so far abstracted analytically.

Williams' version deals with the transformation of certain Foi social relationships: the elder woman strands the younger woman in the treetop and this leads to the latter's marriage. The mother strands her children on the ground and this leads to the transformation of these children from siblings to a married couple. Beyond this, it is difficult to draw any further conclusions concerning the relationship between the several parallel series of transformations. Why should the shift from (female) gathering to (male and female) animal husbandry be mediated by movements along an arboreal axis? Why should the transformations between marriage and siblingship be similarly expressed? And why should the successive series of social relationships be paralleled by a succession of bird species?

These questions I ask in a deliberately rhetorical fashion as a foil for introducing my own version of the myth, which serves to clarify some of the above points. The myth that Williams recorded as a single story I heard as the following two separate and unrelated myths.

The Hornbill Husband

Once there lived a young woman. She was working in her garden one day when a ka buru approached her and said, "Sister, my hagenamo leaves are ready to pick and I want to gather them. But since I am too old to climb up the tree and pick them, I have come to ask you to help me." The young woman agreed and they left. When they approached the hagenamo tree, the ka buru said to the young woman, "Remove all your clothing and leave it at the base of the tree here; take my clothing instead before you climb up." The young woman did so and climbed up the tree. While she was in the top branches picking leaves, she heard the ka buru whispering to herself below. "What is she saying?" the young woman wondered and called out to the ka buru . "No, it is only that some biting ants have stung me," the older woman replied. Then the young woman heard the sound of the tree truck being struck repeatedly. "Now what is she doing?" she wondered. The ka buru called out to her, "I am going to marry your

Figure 10.

Structure of Williams' Version of the Myth "The Origin of the Kutubu People"

husband. You will stay here and die." And with that, the trunk of the hagenamo tree elongated greatly and the branches spread out in all directions and the young woman was marooned in the top of the tree. She looked down at the ground now far below her and thought, "How shall I leave this place now?" and she cried. That night she slept. In the morning she awoke and found that someone had built a fireplace and a small house. In this house she lived. At night while she slept, someone had fetched firewood and with this she made a fire.

She lived in this manner in the little house in the hagenamo treetop and presently she became pregnant. She continued to live in this manner, and then she bore a son. She gave birth to this child in a small confinement hut that someone had built for her. The unseen provider also began to bring food for the small infant boy as well as the mother. When the child grew up to be a toddler, one night the woman merely pretended to be asleep. Waiting there in the dark, a man arrived and held the child. The woman quickly arose and grabbed the man's wrist. He said to the woman, "Release me," but she refused. Finally, the man said to her, "The ka buru who trapped you here is married to your husband. But here near this tree where you live, they will soon come to cut down a sago palm. You must make a length of hagenamo rope and tie one end onto the middle of the sago frond. In this manner, you may pull yourself and your child onto the top of the palm. When they come to cut down the palm, you can then jump off and return to the ground." The woman did as the man instructed her, and with the aid of the rope she and her child pulled themselves onto the sago palm.

The ka buru and her husband arrived to set up the sago-processing equipment. While the ka buru erected the washing trough, the man began to chop down the palm. When it fell, he went toward the top to remove the fronds and gave a cry of surprise when he saw his other wife sitting there with a child. The ka buru heard his exclamation and called out to him, "What is it? "No," he replied, "Some wasps have stung me." The ka buru asked suspiciously, "You haven't found another woman perhaps?" The man meanwhile looked at his long-abandoned wife and was filled with shame. He brought her over to where the ka buru was making sago and the two women continued working together. They all returned when the task was done and lived together.

The two women began making a garden together, but the ka buru would constantly shift the boundary marker between her ground and the younger co-wife's ground, making her own bigger. The younger woman repeatedly moved the marker back to its proper place and the two eventually fought. The husband discovered their quarrel and blaming the younger wife, hit her on the head with a stick, drawing blood. The young woman became very disconsolate and remembered the words of her treetop husband: "While you live with your husband on the earth, I will be around. If he mistreats you, call out to me, I will be flying in the sky above." For he was really a hornbill and his name was Ayayawego or Yiakamuna. Now the young woman called out to him "Ayayawego, Yiakamuna, come fetch

me!" There she waited and she heard the cry of the hornbill. It approached and grabbed the woman by her hair and pulled her up along with her child. They then returned to their treetop home. The overwrought husband cried, "Come back, wife!" But in vain. At the same time, the ka buru turned into a cassowary and crying "hoahoa," she departed. That is all.

The Origin of the Foi People (or, The First Married Couple)

There once lived a man and his sister. Each day, the woman went out to make sago, but she would be gone an inordinately long time. She would not return in the late afternoon with food and firewood or sago but seemingly came back late every night. "What is my sister doing? the man wondered. One time when the woman left, her brother followed her. Downstream they traveled, and he saw her arrive at a tamo tree [arecoid palm]. He watched her climb up the tree and slide down, climb up and slide down, doing this repeatedly. He saw that the trunk of the tree was worn smooth from this activity. When she departed, the man took a sharp flake of obsidian and stuck it in the middle of the tree. The next time the woman went to slide up and down the tree, the stone knife cut a gash where her vagina belonged; before this time, she had had no female sexual organ. Meanwhile, the brother waited at the house but his sister did not arrive. He waited and waited and finally he returned to the tamo tree. He found her, seemingly dead, her skin yellow from loss of blood. The man gathered all manner of leaves and tried to stop the flow of blood from the wound but was unable to. The leaves he used in his attempt to stop the bleeding became colored red, and all the present-day trees with red leaves are the ones the brother first used to stop his sister's bleeding. He then tried the point of a pearl shell and when he rubbed this on the wound, the bleeding stopped a little. He then used the tail of a marsupial and the blood flowed less strongly still. Finally, he took a pig's rope and tried to stop the remaining blood and it finally ceased. He tied the pearl shell to the wound with a piece of bark cloth. When the sister recovered, the two became husband and wife and had sexual intercourse. From their offspring the Foi people originated. That is all.

The first myth now presents a more coherent theme: that of the hostility of co-wives. Foi co-wives can address each other both by the reciprocal term garu (co-wife) and by the reciprocal term boba , which is also the term used between female siblings. The myth therefore draws a contrast between women who are separated by their respective marriages to different men, and an opposed image of their difficulties in living together as co-wives of the same man. In other words, it presents a sustained moral comparison between monogamy and (sororal) polygyny. It is important to understand that sororal polygyny is the unmarked form of plural marriage for the Foi at the conceptual level, for reasons that will become apparent.

Nor is this the only way in which this contrast is depicted in the

Figure 11.

Structural Oppositions in the Myth "The Hornbill Husband"

first myth. The Foi say that the hornbill and the cassowary are "cross-cousins" to each other. In a different tuni , they describe how originally the hornbill inhabited the ground and the cassowary flew in the skies. Dissatisfied with their respective zones, they decided to switch. From that point on, the cassowary became a terrestrial bird and the hornbill assumed the aerial realm. Foi men then add that one should not make a snare trap for cassowaries if a hornbill is flying overhead at the time—the bird will see the trap and warn his cassowary cross-cousins to avoid it.

The contrast between the two trees and this version of the myth is also more easily understood: the hagenamo tree, the gathering of whose leaves and fruits is female work, contrasts with the sago palm, the exploitation of which requires intersexual cooperation. The descent by the young woman and her child by way of the sago palm thus signals her entry into a conventional marital domestic arrangement. I have diagrammed the relevant oppositions in figure 11.

The focus of hostility between the two women shifts from a vertical separation and arboreal entrapment in the beginning to the elder co-wife's furtive movement of the garden boundary marker along the horizontal axis in the latter half of the myth. Analogously, the two

women compete for exclusive access to a single husband in the first half and compete for exclusive rights to a piece of garden land in the second half. The story thus encompasses a commentary on the relative difficulties of polygyny and its resolution through the separate marriages of women. By portraying the two women as complementary avian species, the myth emphasizes the necessity of their separate and contrastive marital destinies: in other words, monogamy is the means by which the hostility of co-wives can be mitigated.

What then is the relationship between this myth and the second myth, which Williams recorded as a single tale? A transition between the two myths is missing in the version I collected, so that the vertical separation of the hawk's wife and her children is no longer a structurally relevant episode. Nevertheless, the second myth seems to invert the first in several key respects. "The Hornbill Husband" begins with a pair of females who become co-wives and therefore nominal siblings (since "co-wife" equals "sister" [female speaking] in Foi terminological usages), while the second myth begins with a pair of cross-sex siblings. The sister in the second myth abandons her female role in order to slide up and down a tamo palm (an arecoid species found in sago swamps but which bears no fruit or other edible part), while the younger woman in the first tale is trapped in a hagenamo tree by the elder ka buru .

The brother wounds his sister and creates her vagina and her menstrual ("reproductive") capacity in the second myth, while the husband in the first myth wounds his younger wife on the head, drawing "non-reproductive" blood from that part of the body which is for the Foi both diametrically and conceptually opposed to the sexual organ.[3] In several other Foi myths, the drawing of blood from a woman's head by a man is a figurative expression of having marked her by paying betrothal or bridewealth installments. Both wounds, however, lead to key moral separations: the separation of co-wives into their respective monogamous marriages, and the figurative separation of the sibling-ship of the brother and sister. The brother's actions in staunching the bleeding represent the proper sequence of bridewealth prestations: shells, game, and finally pigs, as I described it in chapter 5. By so doing, he converts his sister's newly created reproductive capacity into that of a wife's. This can be interpreted as a figurative statement on the dependence of Foi men on their sister's bridewealth for securing their own wives (see figure 12).

But a more complete analysis of the relationship of the two myths

Figure 12.

Inversion in Myths "The Hornbill Husband" and "The Origin of the Foi People"

would have to account for the themes of male and female subsistence activities woven into the plot of the first myth, and the exclusive preoccupation with the creation of bridewealth media in the second. I now present an obviational analysis of these myths in order to demonstrate that certain analogical equivalences are created in the plots which cannot be accounted for by structural analysis alone.

I begin with my version of "The Hornbill Husband" and present it, as I have suggested, as a series of substitutions. An elderly ka buru (literally "black woman" or in other words, an ogress), approaches a young woman and persuades her to leave her gardening work and help her gather edible hagenamo leaves (substitution A : [gathering] edible leaves for gardening; cooperative for solitary female activity). At the tree, the elder woman tells the younger woman to change clothes with her and ascend the tree (B : young woman's clothing [= identity] for elder woman's). Then, by a magical process, the ogress causes the hagenamo tree to elongate, trapping the younger woman. She then departs, announcing her intention of marrying the young woman's husband (C : elder wife for younger wife; treetop for ground). Substitution C now obviates A by revealing the hidden treachery of

the elder woman's offer of cooperation in gathering edible leaves, and completes the replacement of the elder woman in the younger's implicitly revealed marital household.

The turning point of the myth occurs when the young woman discovers that she is being supplied with food and shelter by an unseen provider (D : arboreal [male] nurturance for terrestrial [female] treachery, hence obviating A). This substitution also obviates A by introducing the new marital destiny of the young woman: her arboreal phantom husband has replaced her unidentified ("phantom") terrestrial husband.

Revealing himself, the hornbill husband tells his new wife how she may rejoin her terrestrial husband by shifting to the top of a nearby sago palm that the latter is due to cut down (E : sago palm for hagenamo tree), obviating B by creating the opposed vertical orientations of the sago palm and the hagenamo tree: one must climb up the hagenamo tree to gather its leaves, while one must cut down the sago palm to appropriate its starchy interior. The final substitution occurs when the husband rediscovers his first wife (F : terrestrial husband for hornbill husband), reversing (and hence obviating) the treachery of the elder woman represented in substitution C . The final substitution also returns the myth at this point to its original substitution, but in significantly altered form: the myth began with the competition between two women for a husband and ends with their ironic marriage to the same man, in which they would be expected to cooperate (as co-wives or "sisters").

The facilitating modality represented by substitutions ACE details the transformations in the relationship between the two women, while the motivating modality represented by substitutions BDF details their competitive relationship to husbands, impelling their assumption of a co-wife relationship (see figure 13). But the plot of the myth continues past the point of obviation. How does its additional resolution relate to the initial figurative construction I have already exposed?

If the facilitating and motivating modalities can be taken as whole metaphors themselves, then their relative positions can be reversed or inverted. In other words, if the relationship between women and their husbands can transform the relationship between women themselves then, logically, the inverse is also possible: the relationship between women can motivate the transformation of their marital statuses. The remainder of the plot of the "The Hornbill Husband" inverts the terms of each of the previous successive substitutions, turning triangle ACE

Figure 13.

First Obviation Sequence of "The Hornbill Husband"

into the motivating modality of triangle BDF , which facilitates it. And if this is so, then the order of the substitutions themselves must be inverted. Recall that D represents the "highest point" of separation between the two women, while the initial point A began with their nominal cooperation. The inversion of the first obviation sequence must therefore necessarily begin at its midpoint, D , and return in inverted form to that point, completing the substitutive sequence

The next substitution thus occurs when the younger woman rejoins her husband and new co-wife in a conventional domestic household (inverse D : terrestrial for arboreal marriage). The two women return to garden making (inverse C : gardening for gathering of edible leaves; horizontal for vertical separation). The elder wife attempts to encroach on the younger woman's ground (inverse B : appropriation of land [marital identity] for appropriation of clothing [individual identity]). This leads to their physical fighting and the husband's wounding of his young wife's head (inverse A : fighting [between co-wives] for cooperation). In anguish over her unfair treatment at the hands of her terrestrial husband, she calls out to Ayayawego, her benevolent aerial husband (inverse F : hornbill husband for terrestrial human husband). The hornbill returns her to her arboreal home (inverse E : return to arboreal home for return to terrestrial home). It is understood in the myth that this effects the young woman's transformation into a female hornbill herself. Having finally been separated by husbands who inhabit complementary and distinct spatial zones, the women themselves complete the terms of this complementarity: the hornbill wife versus the cassowary wife, once again obviating the quasi-sororal identification of the two women made in the opening of the myth.

My task now is to reintegrate the second myth into this sequence. I am obliged to do so solely on Williams' ethnographic evidence that the Foi of Lake Kutubu did once relate the two tales as a single myth. But it is my assertion, which I will prove with other examples in the next four chapters, that in such cases these double myths are separated and/or reintegrated precisely at the point of obviation . For I now show that the second myth simultaneously inverts both obviation sequences of "The Hornbill Husband" as I have just interpreted them.

"The First Married Couple" begins with a brother and sister who live as an intersexual domestic unit (substitution A , inverting D of the previous myth: cross-sex sibling complementarity for marital complementarity). Curious as to his sister's failure to provide her share of

food, the brother discovers that to the neglect of her domestic responsibilities, his sister instead regularly engages in metaphorical copulation with a tamo palm (substitution B , inverting C of the first myth: nonedible treetop for hagenamo treetop. It also inverts C in the following way: in the first myth, the young woman is helplessly trapped as the tree itself elongates; in the present tale, the tree remains passive while the girl herself moves up and down. The young woman in the first myth becomes trapped in the course of carrying out a normal female subsistence task; the sister in the present myth remains unconstrained in the course of neglecting her domestic responsibilities [thereby revealing what the Foi articulate as the conceptual contrast between sexual intercourse and subsistence activity]). The brother then inserts a sharpened stone into the trunk of the tree (substitution C , inverting B of the first myth: placing an obstacle in the sister's vertical progress, for the elder woman's placement of an obstacle [the garden boundary marker] in the young woman's horizontal gardening progress). Sliding down the palm, the sister slashes herself, releasing the first menstrual blood (substitution D , inverting A of the previous myth: substituting a wounded sexual organ for the younger wife's wounded head). The brother finally stops the bleeding with a conventionally correct series of wealth objects (substitution E , inverting F of the first myth in a rather complex fashion: the hornbill husband reclaims his young bride not merely because of her supplication but by virtue of the fact that he provided her with food and shelter and bore a child by her. The brother in the second myth claims his sister's reproductivity by accumulating the proper sequence of wealth objects. In all respects, this is a metaphorical inversion of the conventional Foi definitions of cross-sex siblings versus husband and wife relationships. A brother expects to exercise control over his sister's bridewealth because he nurtured her with food and other domestic necessities during her lifetime. A husband by contrast repays his wife's brother for such nurturance by making payments of wealth objects). Finally, the brother and sister become the first married couple, the ancestors of all the Foi people (substitution F , inverting E of the previous myth: ground-dwelling human marital pair for arboreal hornbill marital pair; terrestrial human progeny that are nevertheless totemically banima birds [who always inhabit the ground] for arboreal human marital pair who are hornbill birds). In figure 14 I have superimposed in italics the obviation sequence of the second myth onto the inverted myth of the "The Hornbill Husband."

Figure 14.

Inversion of First Obviation Sequence in "The Hornbill Husband"

and Parallel Obviation Sequence of "The First Married Couple"

The three substitutions of triangle BDF of the second myth in figure 14 represent the motivating modality. They detail the transformation of the sister into a wife. The facilitating modality of triangle ACE by contrast focuses on the transformation of the brother's role, from the provider of male subsistence products to the provider of the bride-wealth items with which he transforms his sister's reproductive capacity. In other words, although the myth itself represents an inversion of the inverted sequence of the first myth, "The Hornbill Husband," the relative positions of the facilitating and motivating modalities parallel that of the first obviation of the first myth. Hence the two sequences in their entirety metaphorize each other, and one can readily understand why Williams recorded them as "one myth." By juxtaposing the two tales, an analogy is revealed between the moral necessity for women to separate in marriage and the corresponding necessity that men have to separate themselves from their sisters by "turning them into" sources of bridewealth for their own wives. That these two mythical statements correspond to one of the quotidian preoccupations of Foi women and men respectively is demonstrated by the fact that I was always told "The Hornbill Husband" by a woman and "The First Married Couple" by a man. The two myths establish as metaphors of each other the complementarity of wives separated by marriage (represented by the respective final arboreal and terrestrial domains of the two women in "The Hornbill Husband") and the simultaneous complementarity of brothers and sisters and of husbands and wives.

If one were to follow Lévi-Strauss, it might be said of these myths that: (1) the progress between arboreal and terrestrial zones; (2) the progressive transformation of humans into birds; and (3) the successive replacement of intersexual domestic-subsistence activities serve as codes for the expression of parallel transformations between sibling and affinal relationships. Speaking in a similar manner of the logic of totemic differentiation, Lévi-Strauss maintains that they

constitute codes making it possible to ensure, in the form of conceptual systems, the convertibility of messages appertaining to each level [of a single culture]. (1966:90)

The significance of this convertibility obliges the analyst to correlate the objective differences between various natural species with correspondingly differentiated social categories. But I maintain that such objective differences are themselves created in the course of tropic con-

structions within a single culture. In the myths I have just analyzed, it can well be said that rather than the difference between hornbill, cassowary, marua , and banima species serving as a code for the differentiation of Foi kinship statuses, the reverse is equally true. In the same vein as Mauss offered his analysis of magical symbols (see discussion under "Magic," chapter 6), I dispute that this relationship between avian species reflects some objective connection between them. The hornbill and marua come to express figuratively a male and female marital unit, and do so in its nurturative aspects: the hornbill provides male sustenance while the female marua in Williams' version of the myth bears and succors children. Likewise, the Foi idea that the hornbill and cassowary are cross-cousins to each other, and hence figuratively depict the complementarity of cross-cousins in ecological terms, is another construction, itself serving as a foil in the plot of the myth for the comparison of the moral content of two different kinds of interpersonal differentiation (that between co-wives and that between husband and wife). To say that one differentiation serves as the fixed source of the other is misleading, since what myth does precisely is create the context of their mutual definition and delineation (cf. Kirk 1970:43; Lévi-Strauss 1963:215).

Furthermore, I have suggested that since each myth is itself a self-closing image, a series of successive substitutions that culminates in the creation of a single tropic construction, then the transformations between myths that Lévi-Strauss identifies throughout the four volumes of Mythologiques remain, in my terms, culturally unmotivated. Hence, Lévi-Strauss can only reduce such transformations, as I have said, to a set of objective or naturally derived oppositions. Their tropic basis as signifiers within a metaphorically created system of cultural meanings are sacrificed to their purely lexical or referential status. But nature is itself only created reflexively as a cultural construct; its reality bears a determinate relationship to the semiotic parameters of a symbolically constituted cultural domain.

Boon and Schneider (1974) have criticized Lévi-Strauss for failing to provide a holistic relation of a single culture's mythology to the total social facts of its particular and individual sociality. Despite Levi-Strauss' suggestion that "myth itself provides its own context" (1963:215), his enterprise is based on the deliberate decontextualization of mythic fragments. That is why Lévi-Strauss does not feel obliged to draw more than intermittently throughout Mythologiques on the nonmythical cultural elements of the societies whose myths he compares, though certain key facts he gleans from the associated eth-

nographies aid him in delineating the oppositions and transformations in mythical themes from culture to culture.

What obviational analysis obliges us to do is precisely the opposite: to consider the entire corpus of a single culture's mythology as a related set of moral statements on a unique set of cultural valuations. Let us begin not with a set of transcendental oppositions such as nature and culture, naked and clothed, raw and cooked, and so forth, but rather with the paradigmatic analogies I have analytically extracted in the two obviation sequences I discussed in the beginning of this chapter (figures 7 and 9).

As I have noted, if Foi sociality had to be expressed in a summating analogy, it would be the creation of affinity out of intersexuality and vice versa. The transformation of one to the other (and both out of life and death) depends upon the type of complementarity involved between these categories, which in turn is characterized by particular kinds of exchanges. Thus, men and women exchange complementary foodstuffs, affines exchange contrastive wealth items, and so on.

Thus, although the myths that now follow tell us much more about Foi society than is expressed in this simple equation, I have grouped them into four chapters according to their relationship to themes of male and female sexuality, affinal mediation, and the nature of complementarity and exchange themselves. In the course of focusing attention on certain metaphorical substitutions, each myth unfolds its own perspective on this analogy (and hence on one of the substitutions in the secular obviation sequences of Figures 7 and 9), until the analogy itself becomes refracted into many different statements. Indeed, perhaps the most appropriate way to introduce these myths is with the observation of Franz Boas, which also precedes Lévi-Strauss' original outline of his analysis of myth (1963:206): "It would seem that mythological worlds have been built up only to be shattered again, and that new worlds were built from the fragments."