The Mask As Metaphor

The Olmec Were-Jaguar

From the standpoint of Aztec civilization, Huitzilopochtli is of major importance, but from a

broader perspective encompassing all of Mesoamerica and adding the temporal dimension that allows a view ranging back as far as archaeology permits us to see, Huitzilopochtli pales into insignificance; he was only a god of the Aztecs. But the figure with whom he shared the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlán suffers no such fate. Tlaloc, the god of rain, associated always with storms and lightning, has his roots deep in the Mesoamerican past. To understand the complex of symbols comprising his characteristic mask is to understand something fundamental about Mesoamerican spiritual thought, because that mask has its readily identifiable counterpart in every civilization that played a role in Mesoamerican culture and because, like Tlaloc, the figure identified by the rain god mask is in every case involved not only with the provision of the life-sustaining rain but also with divinely ordained rulership and several other equally fundamental themes of Mesoamerican spirituality. Thus, the mask of the rain god provides a particularly good example of the way Mesoamerica as a whole constructed metaphorical masks to delineate its gods.

Tlaloc, the Aztec incarnation of the complex of symbols associated with rain, is the rain god we know most about because, as with Huitzilopochtli, we have the evidence of the codices and the chronicles to supplement and clarify the information we can glean from the remains of art and architecture. The earlier civilizations of the Classic and Preclassic periods left us no such explanatory material. But although there has been some dispute about whether it is possible to use the information regarding Aztec culture to explain symbolic visual images from earlier cultures,[27] our analysis of rain god imagery that follows suggests that this particular complex of images can be traced from its origins in the relatively dim past to the time of the Conquest. It is undeniable[28] that certain symbolic visual traits occur in combinations consistently connected with rain. At times, it is possible to "read" the meanings of particular symbols even from very early times, and when it is possible, these meanings coincide remarkably well with those suggested by working backward from later times. Mesoamerica, after all, was one culture, however complex, with one mythological tradition. The complexity of cultural development over a large geographic area and a time span of three thousand years will necessarily cause difficulties for our full comprehension of its fundamental unifying themes, but the unity is always tantalizingly present; we must attempt to find it amid the artifacts archaeology provides for us.

What is easiest to demonstrate about the continuity of Mesoamerican spirituality from the earliest times is that the characteristic Mesoamerican way of constructing "gods," or masks, by combining a variety of natural items, that is, constitutive units, in unnatural ways begins very early and that certain combinations recur from those early times until the Conquest. The mask associated with the complex process of the provision of water by the gods, a process involving caves, underground springs, and cenotes as well as rain with its accompanying thunder and lightning is a case in point; the remarkable similarities in imagery in the features of the masks of the rain gods, a term we will use to denote this whole complex of associated meanings, created by each of the cultures of the Classic period in Mesoamerica certainly suggest the existence of a shared prototype in earlier, Preclassic times.[29]

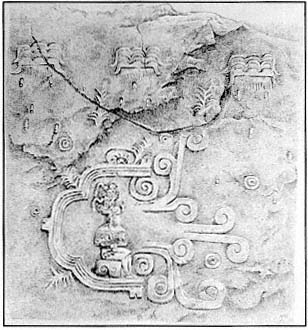

That prototype can be found in the first high civilization in Mesoamerica—that of the Olmecs. This argument was made clearly and forcefully as early as 1946 by Miguel Covarrubias, who constructed a chart (pl. 2) showing "the 'Olmec' influence in the evolution of the jaguar mask into the various rain gods—the Maya Chaac, the Tajin of Veracruz, the Tlaloc of the Mexican Plateau, and the Cosijo of Oaxaca."[30] But the tremendous number of archaeological discoveries and the equally large body of scholarly thought devoted to the Mesoamerican material since Covarrubias advanced this idea have revealed levels of complexity neither he nor anyone else imagined at that time. It is therefore doubly remarkable and a tribute to his deep intuitive understanding of the spiritual art of Mesoamerica that the Covarrubias hypothesis has held up quite well. That hypothesis, however, must now be understood in the light of more recent developments, which necessitates an explanation of recent thought regarding Olmec spirituality in general which, however, has clear implications concerning the fundamental nature of Mesoamerican spiritual art of all periods. That done, we can return more meaningfully to the features of the Olmec mask associated with rain.

Covarrubias, in addition to seeing the jaguar as involved with rain, believed that the jaguar "dominated" the art of the Olmecs and that "this jaguar fixation must have had a religious motivation."[31] As his chart suggests, however, it is not the jaguar himself who dominates Olmec art but rather the composite being who has come to be known as the were-jaguar, a creature combining human and jaguar traits. As Ignacio Bernal notes, "when one attempts to classify human Olmec figures, without realizing it one passes to jaguar figures. Human countenances gradually acquire feline features. Then they become half and half, and finally they turn into jaguars. . . . What is important is the intimate connection between the man and the animal."[32]

The contentions of both Covarrubias and Bernal must be further qualified by acknowledging the hypothesis of Coe and Joralemon regarding the Olmec gods, a hypothesis based on a recently dis-

Pl. 2.

Covarrubias' graphic representation of the evolution of the mask of the Rain God

from an Olmec source, which we designate Rain God C, through the Oaxacan Cocijo, in the

left-hand column, the Tlaloc of central Mexico in the next column, followed by the

Gulf coast rain gods and finally, those of the Maya in the right-hand column.

covered Olmec sculpture, the Lord of Las Limas (pl. 3). As Coe noted, the knees and shoulders of the seated figure are incised with "line drawings," in typical Olmec style, of masked faces. Joralemon later discovered another mask incised on the figure's face which, with the mask "worn" by the infant, brought the total of distinctly different masked faces to six. After a great deal of analysis of the corpus of Olmec art by Joralemon, he and Coe have argued "that the Las Limas figure depicts the Olmec prototypes of gods worshiped in Postclassic Mexico" and that "Olmec religion was principally based on the worship of the six gods whose images are carved on the Las Limas Figure." Furthermore, Joralemon concluded that

the primary concern of Olmec religious art is the representation of creatures that are biologically impossible. Such mythological beings exist in the mind of man, not in the world of nature. Natural creatures were used as sources of characteristics that could be disassociated from their biological contexts and recombined into non-natural, composite forms. A survey of iconographic compositions indicates that Olmec religious symbolism is derived from a wide variety of animal species.[33]

Thus, Coe and Joralemon would probably not agree with Covarrubias's contention that the jaguar dominated Olmec religious art, but they continue to believe, as Covarrubias did, that there is a demonstrable continuity linking Olmec and Aztec gods.

Predictably, their theory caused tremendous controversy. Some objected to the argument from the analogy with Aztec and even more recent spiritual traditions; Beatriz de la Fuente, for example, objected to Coe's identifications on the grounds that they were

based on a comparison of the Aztec with the Olmec, the cultures having between them a span of some 2000 to 2500 years. They seek explanations for ancient forms in activities or beliefs of present-day peoples, whose societies have, furthermore, suffered the inevitable effects that result from the clash of native and western cultures .[34]

Another form of objection concerned the equation of certain traits with certain fixed and specifically defined gods. Contending that Joralemon had artificially isolated and emphasized certain visual features at the expense of others and neglected to pay sufficient attention to the complexity and fluidity of the combinations of features, Anatole Po-

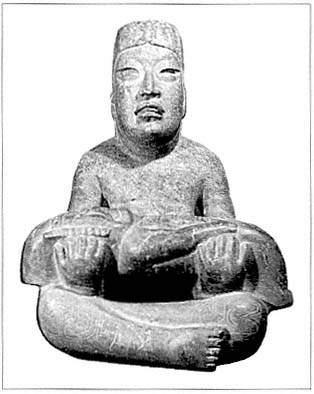

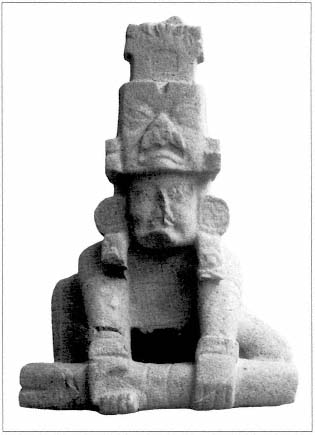

Pl. 3.

The "Lord of Las Limas," Olmec sculpture from Las Limas,

Veracruz; dimly discernible in this photograph are the masked

faces incised on the figure's face, shoulders, and knees; the

face of the child held by the figure is an excellent example

of our Rain God CJ (Museo de Antropologia de Xalapa).

horilenko maintained that "there are no Olmec compositions which consistently depict recurring combinations of the same referential signs. . . . For instance, a four-pointed flaming eyebrow is not exclusively and consistently used with a jaguar mouth showing slit fangs and an egg-tooth. "[ 35] Thus, both de la Fuente and Pohorilenko suggest, in rather different ways, that the Coe-Joralemon hypothesis is too rigid, too specific in its identification of the gods of the Olmecs.

Accepting these objections, however, neither invalidates nor trivializes the fundamental insight at the heart of the argument advanced by Coe and Joralemon: Olmec religious art, rather than betraying a fixation on the jaguar, presents a variety of composite beings, each delineated in a characteristic mask and each a symbolic construct derived from a variety of natural creatures. Furthermore, these varied figures must be seen as the component parts of an all-inclusive system that mediated between man and the powerful forces originating in the world of the spirit. While it is possible to feel that the identification of specific Olmec figures with specific Aztec gods is unwarranted, it seems unarguable that, as Coe and Joralemon have allowed us to see, the Olmecs created a mediating system of gods to establish a relationship between man and the world of the spirit in precisely the same manner as did the Aztecs, their distant Mesoamerican heirs. There is, then, a demonstrable continuity linking Olmec and Aztec spiritual thought. In fact, the Olmecs are the likely originators of this characteristic Mesoamerican practice of creating a spiritual system composed of a large number of interrelated "gods," each of which is represented by a mask and costume made up of symbolic features. The seemingly endless parade of Mesoamerican gods tricked out in their fantastic regalia probably begins at La Venta.

These gods can be seen in Olmec religious art, but when one looks closely at the way they are depicted, the identification of particular clusters of features as specific, recurring deities does not seem as simple as the Coe-Joralemon hypothesis suggests. Two sorts of complexity must be reckoned with. First, three distinct categories of figures exist in Olmec art despite the fact that some figures straddle the boundary between two categories. Only one of these categories is made up of figures that stand as metaphors for the supernatural, that is, the Olmec "gods." Second, even within that category, there are, as Pohorilenko points out, a very large number of combinations of the basic repertory of symbolic features.

The first of these levels of complexity is easiest to deal with. Although all Olmec art is essentially religious,[36] that religiosity expresses itself in three different ways, sharing only a fascination with natural forms, especially the form of the human body. The first category glories in the presentation of the human form and countenance in all its ideal beauty. Perhaps the best example of this is the sculpture from San Antonio Plaza, Veracruz, which is often called The Wrestler. Its sensitively realized dynamic pose and clearly but delicately delineated physical features reveal the Olmec artist's desire and ability to idealize the human body as a purely natural form of beauty almost spiritual in its compelling vitality. And that elusive spirituality is also hinted at by the slightly downturned mouth suggestive, of course, of the symbolic were-jaguar. The well-known colossal heads and the characteristic jade and jadeite masks, both realistic enough to suggest portraits,[37] often evoke the ideal beauty of the human countenance and similarly hint at man's basically spiritual nature.

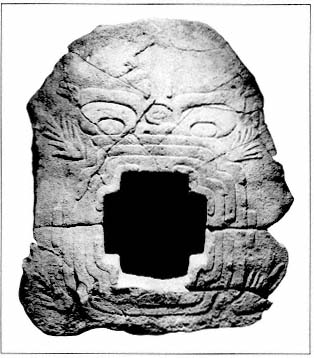

Opposed to these realistic depictions of human features, a second category of Olmec art depicts fantastic composite beings whose faces are masks comprised of natural features combined in strikingly nonnatural ways, denizens of the world of the spirit rather than the world of nature. Though the human body provides the basic form for the sculptures, they are clearly not human. San Lorenzo Monument 52 (pl. 4), which is analyzed in detail below, serves as an excellent example of the type. Everything about it—its combination of fa-

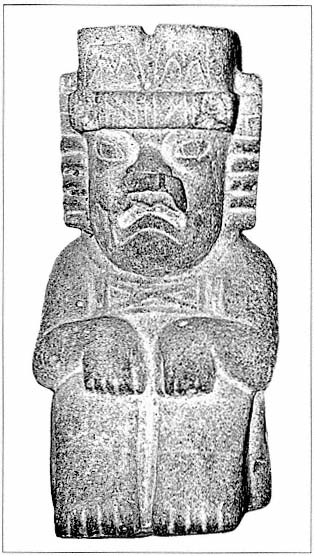

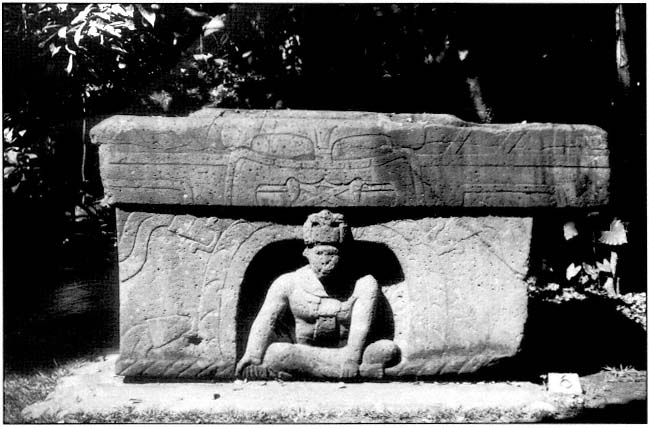

Pl. 4.

Monument 52, San Lorenzo, our "Rain God CJ"

(Museo Nacional de Antropologia, México).

cial features, its human body with nonhuman hands and feet, and its stylized form and unnatural proportions—proclaims it a mythological creature rather than a natural one. As anyone even slightly familiar with Olmec art is aware, such composite beings, once thought to be primarily were-jaguars, are so frequently depicted as to be practically characteristic of that art. These composite beings are, collectively, the Olmec metaphor for the domain of the spirit, a domain that could be conceptualized only by departing from the order inherent in the natural world. No doubt the Olmecs, like their Mesoamerican heirs, saw a creator god, their prototype of an Ometeotl, in this spiritual realm, a creator who was not depicted, a force so essentially spiritual that it could not be encompassed and ordered by human thought. The mythological creatures who populate Olmec art are the "unfoldings" of this spiritual essence.[38]

Significantly, there is a third category of Olmec artistic representation that mediates between the first two diametrically opposed categories. It depicts realistic human beings, as does the first type of Olmec art, but they are masked and costumed to resemble the mythological creatures of the second type. Mural I of Oxtotitlán, Guerrero (pl. 5), provides the clearest representation of such a figure. The seated man is depicted x-ray fashion, as the Maya were to do later,[39] disclosing the realistically rendered human being within the fantastic birdlike disguise. These are ritual figures, and we will explore their symbolic dimensions in the later discussion of the mask in ritual.

These three categories of Olmec figural representation—human, mythological, and ritual—reveal an Olmec conception of the universe basically the same as, and thus the logical prototype of those of, the later cultures of Mesoamerica delineated in the second part of this study. For the Olmecs, the world of nature, symbolized in art by the realistically rendered human figure, was imagined as the binary opposite of the world of the spirit, symbolized by the composite beings. The masked ritual figures show man's way of mediating between those two opposed realms. Though her analysis of Olmec art is quite different from ours, de la Fuente grasps the essential nature of that art: "The human figure, the gravitational center of almost all the forms of Olmec art, appears in this art with different metaphysical definitions which, at their extreme, seem to repeat . . the entire order of the universe."[40] Thus, this symbolic art allowed the Olmecs to represent their conception of the cosmic

Pl. 5.

Mural I, Oxtotitlán, Guerrero displaying the x-ray convention

which allows the simultaneous depiction of the features of the wearer

of the ritual mask and of the features of the mask itself

(drawing by David Grove, reproduced by permission).

structure in visual form by symbolically reordering the materials of nature.

Distinguishing carefully between the three different categories of the art through which the O1mecs represented the tripartite cosmic structure allows our discussion of the gods to focus on those works of art representing the fantastic composite beings who symbolized the forces of the world of the spirit. But there is another form of complexity that must also be acknowledged: as Pohorilenko pointed out, the features of these composite beings are not characterized by a limited number of combinations of the same symbolic features. On the contrary, though the total number of features is not great, they are combined in what often seems to the would-be iconographer an endless series of combinations. In view of the limited state of our present knowledge of Olmec spiritual thought—Jacques Soustelle says, "We are overawed by the immense depths of our ignorance"[41] —we believe it would be impossible to determine which of those combinations, if any, the Olmec priesthood identified as named deities. When we think of how little we know of Olmec thought in comparison to the relative wealth of information we have about Aztec spirituality and then realize that even with the knowledge of Aztec spiritual thought provided by the codices and chronicles, there is still a great deal of uncertainty involved in the identification of many Aztec gods represented in art,[42] our difficulties become clear. Fortunately, what we do know of Aztec art can help us to understand their distant forebears.

Our brief analysis of Huitzilopochtli revealed that not all of the symbols associated with him by the Aztec priesthood need be present in any particular depiction of him and, furthermore, that it was possible within the Aztec symbol system to create figures combining the features usually associated with particular gods. We term these combinations "secondary masks" and will discuss them in the conclusion to our consideration of the mask as metaphor for the gods. The Aztec system was an extremely complex one built up—like the calendrical systems of Mesoamerica—through the permutation of a limited set of symbolic features through the range of their possible combinations. If the Olmec system was similarly constructed, and the evidence suggests overwhelmingly that it was, it seems unlikely that, lacking codices and chronicles or other explanatory material, we will ever be able to reconstruct the system as it would have been understood by the Olmec priest.

This is not to say, however, that we cannot "read" particular symbolic features and understand the general ritual or mythological function they probably served. This then enables us to understand the more complex meaning that a cluster of individual symbolic features could carry, but the more complex the configuration, the more general our understanding is likely to be. Thus, a number of such clusters can be shown to refer generally to rain and lightning, vegetation and fertility, and divinely ordained leadership. It is no doubt true that each of the configurations conveyed a particular shade of meaning to the Olmec priest, and it is certainly possible that each of them was a particular "god." It is equally possible, however, that many of them were aspects of one basic spiritual essence, particular manifestations of a single "god." And it is also possible that none of them was thought of as a god at all but rather as a collection of spiritual "facts" joined together temporarily to make a mythological or ritual statement. It is therefore difficult to talk about the gods of the Olmec but not nearly so difficult to discuss the ways the 01mecs symbolized the forces they identified with the world of the spirit. Through an analysis of the individual features that occur on the symbolic masks, we can begin to understand at least this much about Olmec spiritual thought.

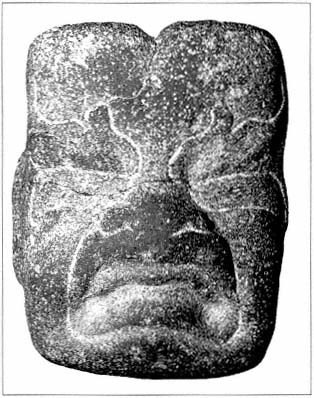

Thus, to return finally to our discussion of the mask representing the rain god, we can concur with Covarrubias, Bernal, and Coe and Joralemon that a mask combining particular features drawn from nature was associated by the Olmecs with the provision of the life-maintaining rain from the world of the spirit. We, and most other scholars who have studied Olmec art, would further agree that the particular "god" associated with rain is a were-jaguar,[43] that is, a mask dominated by the characteristically feline mouth with downturned corners beneath a pug nose. But this general agreement comes to an end when specific masks are discussed. The particular were-jaguar depicted at the bottom of Covarrubias's chart as the archetypical rain god, a stone mask or face panel now in the American Museum of Natural History in New York (pl. 6), differs in several symbolic features from the were-jaguar identified as the Rain God by Coe and Joralemon, a composite figure typified by the were-jaguar child held by the Las Limas figure (pl. 3) and seen clearly on San Lorenzo Monument 52 (pl. 4). Those differences account for Joralemon's seeing the Covarrubias mask (which we will call Rain God C) as representing his God I,[44] "the Olmec Dragon," rather than the Rain God he and Coe have designated as God IV (which we will call Rain God CJ).

These differences should not, however, obscure some fundamental similarities. Both Rain God C and Rain God CJ have generally rectangular faces with cleft heads, pug noses, heavy upper lips, and downturned mouths showing toothless gums. They differ in their ears or ear coverings—C's are long, narrow, and plain while CJ's are long, narrow, and wavy; in their eyebrows—C's are the so-called flame eyebrows while CJ's are nonexistent, replaced by a headband with markings which is part of a headdress; and in their eyes—C's are trough

Pl. 6.

Olmec stone mask, probably architectural, our "Rain God C"

(American Museum of Natural History, New York).

shaped and turned downward at the sides while CJ's are almond shaped and turned upward; CJ wears the typical Olmec St. Andrew's cross as a pectoral while C, being only a mask, of course has no pectoral. Perhaps significantly, the tops of the heads of the two are similar as are the bottoms, that is, the mouth areas. The differences occur in the middle zone of the faces. And it seems even more significant that, to a casual glance, the similarities are far more apparent than the differences; the two faces seem clearly to be variations on a single theme, perhaps the variations that would identify the aspects of a quadripartite god. We believe that an analysis of their symbolic features will demonstrate that a casual glance does in fact reveal an essential truth and that the symbolic features all refer to fertility connected with rain.

Beginning at the top, the first symbol is the cleft head, which Coe and Joralemon evidently do not see as diagnostic since each of their six gods is sometimes depicted with a cleft head and sometimes without. The presence or absence of the cleft, in the light of our earlier analysis of the four Tezcatlipocas whose faces are fundamentally similar with minor variations to indicate their distinct identities, is a tantalizing suggestion that these symbolic faces might also be manifestations of a quadripartite god. Whether this is true or not, however, when one examines the occurrence of the cleft head in Olmec art,[45] several significant facts emerge. First, cleft heads seem to occur only on masks that contain other clearly symbolic features and not on the relatively naturalistic masks and sculpture. This, incidentally, is not true of the symbolic were-jaguar mouth. Second, the cleft appears in two opposed forms, either empty or with vegetation appearing to emerge or grow from it. Third, the empty cleft seems to be found in certain contexts, the vegetal cleft in others. Votive axes were often carved with their upper halves as were-jaguars with cleft heads, but the clefts are always empty.[46] Celts, however, are often decorated with incised masks; when those masks are cleft-headed, the clefts are vegetal. Thus, the appearance of the cleft seems to follow a pattern. These facts would indicate that the presence or absence of the cleft and the form it takes have sufficient symbolic importance to be governed by rules and that it makes a significant contribution to the overall meaning of the symbolic cluster in which it appears.

That the cleft has symbolic importance is further suggested by the fact that it appears only on masks containing other clearly symbolic features and not on the more naturalistic ones. But to understand its function, we must first decipher its symbolic meaning.[47] The fact that the cleft is often depicted with vegetation, probably corn, sprouting from it suggests fertility, and the associations of the other symbolic features on the masks on which it is found with water surely support that connection. As the source of the growing corn plant, it suggests the "opening" in the earth from which life emerges, the symbolic point at which the corn, the plant from which man was originally formed and which was given by the gods as the proper food for man and thus a symbol of life and fertility, can emerge from the world of the spirit to sustain mankind on the earthly plane.

That symbolic connection is reinforced by the fact that the V-shaped cleft, or inverted triangle, has been since paleolithic times a specifically female symbol representing, in human terms, the point of origin of life. Peter Furst discusses the occurrence of this motif in the much later Mixtec codices as a means of identifying these Olmec clefts with "a kind of cosmic vaginal passage through which plants or ancestors emerge from the underworld" and laments the "enormous span of time dividing them" as possibly calling into question the validity of reading Olmec symbols with this Mixtec "language."[48] However, Carlo Gay's discussion of the highly symbolic designs found in pictographic form in shallow caves associated with the Olmec fertility shrine at Chalcatzingo would seem to lay that objection to rest, if indeed these pictographs are contemporary with the Olmec art found at that site.[49] He records the occurrence of "triangle and slit signs [that] are among the most graphic of vulval representations"

among the many sexually related symbols in those pictographs found at a site obviously dedicated to fertility,[50] signs that are identical in shape to the cleft in the were-jaguar head.

That a sexual symbol would occur on the head of a composite being generally seen as remarkably childlike or sexless is perhaps not so strange. The spiritual thought of Mesoamerica is, in a sense, fundamentally sexual in nature. Its ideas regarding the transformative nature of creation through unfolding, which we will delineate in our consideration of the entrance of the life-force into the world of nature (Part II), surely parallel the natural, sexual process of regeneration. Its persistent emphasis on duality—opposites coming together to form a unity—has one of its most obvious examples in the sexual act. Its emphasis on caves as places of origin must surely be connected with the emergence of the child from the womb as the final result of the sexual act.[51] And its common conception of the fertile earth as female clearly has a sexual origin. But the conventions governing Mesoamerican spiritual art did not allow direct expression of this sexual metaphor. Generally speaking, though there are notable exceptions, throughout the development of Mesoamerican art and thought any depiction of sexual organs or the sexual act was taboo. Under these circumstances, it is not surprising that sexual symbols should appear in disguised ways. Although not overtly sexual, the cleft head carries the sexual meaning: it symbolizes creation, especially as that creation takes the form of agricultural fertility, but by extension it can refer to any related instance of life entering the world in the cycle of life and death. Perhaps the vegetal cleft refers directly to agricultural fertility and the empty cleft to the concept of birth and rebirth in a more general sense, especially as it relates to such state-related matters as rulership and sacrifice.

The fertility theme is also the focus of the other symbol the two rain god masks share, the characteristic were-jaguar mouth. The mouth is, of course, far more striking than the cleft, so striking that it has come to be seen as characteristic of Olmec art generally. But before discussing the complex set of symbolic associations it makes, it might be well to clarify what it is since there have been numerous suggestions that it is not a jaguar mouth or even feline. Peter Furst and Alison Kennedy claim that what is represented is the toothless mouth of a toad, the fitting representative of the earth. Terry Stucker and others and David Grove see the mouth as sometimes crocodilian, and Karl Luckert, who sees the facial configuration as that of a serpent, goes even further by claiming that not only is this mouth not that of a jaguar but, aside from three figures, there are no jaguar representations at all in Olmec art.[52] In our view, however, and that of most other Mesoamericanists, the typical were-jaguar mouth is just that, the mouth of a jaguar with some features exaggerated for symbolic reasons and some modified to fit the human facial configuration. The heavy pug nose that is an integral part of the configuration and the general frontal flatness of the mouth segment are typically feline and not at all serpentlike. Furthermore, when the body of the figure on which the mouth is generally found is taken into account, both the posture and numerous anatomical details suggest the jaguar. In addition, the jaguar is indisputably represented with reasonable frequency in Olmec art,[53] and it is an important symbolic creature in every Mesoamerican culture that succeeded the Olmecs and was used by each of them as a source of attributes for its gods. And there are several Olmec sculptures that clearly combine the features of the feline with those of man and that depict the characteristic mask.

But it is important to recognize that while the jaguar is the most likely source of the nose/mouth configuration, that facial feature is a highly multivocal symbol that has meanings other than those related to the creature from whom it was taken. Two of those other meanings can be seen in Monument I (pl. 7) from the Olmec fertility shrine of Chalcatzingo which depicts a figure holding a ceremonial bar signifying rulership seated within a stylized cave mouth that lies under three stylized clouds from which raindrops are falling. The clouds themselves bear a striking resemblance to the heavy upper lip of the were-jaguar mouth, and the cave is that very mouth represented in profile, as is made clear by the appearance above it of an eye bearing the Olmec St. Andrew's cross on its eye-

Pl. 7.

Monument I, "El Rey," Chalcatzingo, Morelos (drawing by Frances Pratt,

reproduced by permission of Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, Graz, Austria).

ball, the same cross found on the pectoral of Rain God CJ and occasionally found on one or both eyes of were-jaguar masks. A further indication that this cave is to be seen as a mouth are the "speech scrolls" issuing from it in typical Mesoamerican fashion.

The identification of the cavity as a mouth is strengthened by another bit of evidence external to the relief itself. A freestanding monument found at Chalcatzingo, Monument 9 (pl. 8), is a frontal view of the were-jaguar mouth/cave represented in profile in Monument I. It has the same eyes and the same ridged mouth with vegetation sprouting from its "clefts" in a fashion reminiscent of the cleft heads, and further suggesting the close relationship between the two symbolic works is the apparent use of Monument 9. According to Grove, the carved slab, when erected for ritual use on the most important platform mound at Chalcatzingo, was designed to be entered: "The interior of the mouth is an actual cruciform opening which passes completely through the rock slab. Interestingly, the base of this opening is slightly worn down, as if people or objects had passed through the mouth as parts of rituals associated with the monument."[54] It replicated the natural cave and allowed the ritual "cave" to be entered through the mouth of the composite being representing the world of the spirit, which the ritual enabled man to contact. The seated figure depicted in Monument I has entered that same liminal zone from which issues the "speech" of the supernatural. Thus, the relief designated Monument I relates the cave to the rain cloud by visually associating both of them with the were-jaguar mouth.

Such an association of caves and clouds seems as strange to us as it did to Evon Vogt when he encountered it in his work with the present-day Maya of Zinacantan. But he learned that in the context of the Mesoamerican environment, it is not so strange.

Pl. 8.

Monument 9, Chalcatzingo, Morelos (MunsonWilliams-Proctor Institute,

Utica, New York; photograph courtesy of that institution).

I have had a number of interesting conversations in which I have attempted to convince Zinacantecos that lightning does not come out of caves and go up into the sky and that clouds form in the air. One of these arguments took place in Paste [ * ]as I stood on the rim with an informant, and we watched the clouds and lightning in a storm in the lowlands some thousands of feet below us. I finally had to concede that, given the empirical evidence available to Zinacantecos living in their highland Chiapas terrain, their explanation does make sense. For, as the clouds formed rapidly in the air and then poured up and over the highland ridges . . . they did give the appearance of coming up from caves on the slopes of the Chiapas highlands. Furthermore, since we were standing some thousands of feet above a tropical storm that developed in the late afternoon, I had to concede that it was difficult to tell whether the lightning was triggered off in the air and then struck downward to the ground, or was coming from the ground and going up into the air as the Zinacantecos believe.[55]

The Olmec connection between caves and clouds apparent on Monument I indicates that today's Zinacantecos have a belief system rooted deep in the past. And that Olmec connection between caves and clouds and the were-jaguar mouth clearly worked in reverse as well; the shape of the mouth called to the Olmec mind caves and rain clouds as well as jaguars.

The connection at Chalcatzingo between these elements is supported by the existence there of numerous miniature, artificial "cavities" linked by a system of miniature carved drain channels[56] evidently designed for the symbolic movement of water in the ritual reenactment at this fertility shrine of the provision of water by the gods. There is also a curious relief carving, Monument 4, that depicts a feline creature, perhaps devouring a man, associated with a branched design that might represent "the pattern of watercourses of the valley north of Chalcatzingo"[57] which would thus flow symbolically from the mouth of the "jaguar." This concern with systems through which water flows is not an isolated phenomenon; the Olmec cave-shrine at Juxtlahuaca, Guerrero, exhibits a comparable, though different, system. These symbolic structures, and others no doubt yet to be found in

the caves of Guerrero, were perhaps the first instances of the jaguar mouth/cave/drain combination that finds its most celebrated example in the carved drain running the length of the cave under the Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacán.

Even more significant for our discussion of the Olmec rain god is the fact that the symbolic use of a system of drains also occurs at all four of the major sites in the Olmec heartland on the Gulf coast, though not in association, so far as we know, with caves. "The complex of artificial lagoons or water tanks on the plateau top and the drain systems associated with them form one of the most unusual aspects of San Lorenzo architecture," according to Richard Diehl, and from an archaeological point of view

the association of Monuments 9 and 52, both of which depict water-related symbolism, with the drain system, the geometric shapes of some of the lagoons, and the fact that the scarce and expensive basalt was used for the drain system instead of wood, all suggest that the system had more than a strictly utilitarian meaning to the Olmec.[58]

All of this, of course, suggests ritual use in the reenactment of the gods' provision of water. Although there are no caves associated with this man-made system of drains and lagoons at San Lorenzo, the fact that the drain channels were carefully covered and that they emptied into the lagoons suggests they may have been used symbolically to recreate the emergence of water from the "heart" of the earth in the fashion of an underground spring feeding a pool of water. One thinks in this connection of the cenotes held sacred by the Maya of the Yucatán.

It is quite significant that the were-jaguar mouth is also linked to this symbol of the gods' provision of water since Monument 52 (pl. 4), one of the primary images bearing the mask of Rain God CJ, "was discovered at the head of the principal drainage system."[59] Further suggesting its relationship to the drain system, the back of the sculpture is fashioned in exactly the same U-shaped form as the basalt stones of which the drain system was constructed. Symbolically, both the drain and the god are "conduits" for the movement of water, the fluid needed to maintain life, from the world of the spirit to the world of man. Whether as the cave mouth or the point at which an underground spring bubbled to the surface, the were-jaguar mouth was surely seen by the Olmecs as the liminal point of mediation between the source of spiritual nourishment located within the essentially female earth and the world of man that existed on the earth's surface. And that mouth was a primary feature of many of the symbolic masks constructed by the Olmecs, masks that, in what was to become the time-honored Mesoamerican fashion, designated the point of contact between the world of nature and the world of spirit, the interface between man and the gods.

But why connect the jaguar with rain? The connection might seem an unlikely one to the modern scholar who probably has never encountered a jaguar outside a book, movie, or zoo and surely hopes never to do so. Similarly, the scholar has been sheltered to some extent by the conveniences of modern urban life from the terrible reality of brutal storms and floods, on the one hand, and drought, on the other. In this respect, the inhabitants of the jungles and forests of Preclassic Mesoamerica knew far more than we do about both jaguars and rain from personal experience as well as from the shared experiences of their group, knowledge that no doubt suggested numerous possible connections between the two. They would have known that the jaguar truly was the lord of the Mesoamerican jungle: it is the largest cat in the western hemisphere, weighing as much as 300 pounds and measuring up to 9 feet in length and almost 3 feet in height at the shoulder[60] and because of its size and power, has no natural enemies. Two other creatures used symbolically by the Olmecs, the crocodilian and the snake, might kill young jaguars, "but adult jaguars regularly hunt full-grown caimans as food" and hunt and eat the giant anaconda.[61] The Olmecs might have had an even stronger reason to respect the jaguar than the fact that it preyed on the most powerful creatures in its habitat. According to a modern guide to game animals,

the jaguar is the only cat in the Western Hemisphere that may turn into an habitual man-eater. There are two reasons for this. One is the jaguar's large size and superior strength. . . . The second reason is that most jaguars live in areas where the natives do not possess firearms. Although the jaguar often has been killed with spears and bows and arrows, it takes an expert hunter to do it."[62]

The formidable power of the jaguar, then, was impressive enough to have served as the basis of a symbolism that continued to exist until the Conquest and to some extent continues even today. As Eduard Seler points out, "the jaguar was to the Mexicans first of all the strong, the brave beast, the companion of the eagle; quauhtli-océlotl 'eagle and jaguar' is the conventional designation for the brave warriors."[63]

The jaguar must also have seemed almost supernatural in its typically feline ability to move almost noiselessly despite its great size and in its surprising ability to move equally well on land, in water, and in the air.

The jaguar is the most arboreal of the larger cats. It climbs easily and well. . . . At those times of the year when its jungle home turns into a huge flooded land, the jaguar takes to the trees and may actually travel long dis-

tances hunting for food without descending. Water holds no fear for the jaguar, and it swims well and fast, frequently crossing very wide rivers. On the ground, jaguars walk, trot, bound and leap. Their speed is great for a short, dashing attack.[64]

These qualities explain why, as Covarrubias discovered, "even today the Indians regard the jaguar with superstitious awe; subconsciously they refer to it as The Jaguar, not as one of a species, but as a sort of supernatural, fearsome spirit."[65]

The storms that lash the Gulf coast—the nortes during the winter months which can bring winds up to 150 kilometers per hour, making coastal navigation impossible, and the hurricanes of late summer and fall with wind velocities over 180 kilometers per hour and tremendous amounts of rain producing destructive floods[66] —make it possible to appreciate the range of possible connections between rain and the jaguar. Rain for the Olmecs was not April showers. In the Veracruz heartland it fell throughout the year and was often accompanied by tremendously destructive storms. Even without the storms, the quantity of rainfall could cause disastrous flooding.[67] In the central highlands, the other area in which a substantial amount of symbolic Olmec art depicting the were-jaguar is found, the more common Mexican rainfall pattern prevails; there are distinct dry and rainy seasons. In that area, a lack of rain at the right time can cause the death of the corn by which man survives. The destruction caused by drought, though different from that wrought by a hurricane and flooding, is just as devastating. The problem for man in these environments is not to "bring rain" as many people think. Rather, man must attempt to bring the elemental forces represented by rain and storm under human control, reduce them to an order that will make the orderly life of culture possible. This, for early man, could only be accomplished through ritual that would enable him to interact with the source of all order, the underlying, otherwise unreachable realm of the spirit.

The ritual control of the rain-related forces probably involved the jaguar because it was the animal equivalent of the storm, equally powerful, equally sudden in its attack, equally destructive of human life and order. Furthermore, the jaguar was at home both in water and in the trees from which it was able to fall, like the storm, on its prey. Like the storm, it was a force that revealed itself in the natural world outside man's control, a force that could be seen as symbolically at the apex of the "unordered," wild forces of nature. By creating the were-jaguar mask, the Olmecs combined the creature who epitomized the forces of nature with man, the epitome of the force of culture. In typical Lévi-Straussian fashion, they created the were-jaguar mask as the dialectical resolution of the binary opposition between the untamed forces of nature and the controlled force of man. While the jaguar hunts with natural weapons (teeth and claws), lives entirely from hunting, and eats his prey raw, man hunts with artificial weapons for food that is a supplement to his staple diet derived from cultivation and eats his food cooked. The jaguar, though generally remaining in the same area, seldom has a den, "usually curling up to sleep in some dense tangle or blowdown,"[68] while man constructs a dwelling and returns to it each night. The jaguar acts instinctively while man can act rationally. In a sense, then, man and jaguar are equal opposites, and the were-jaguar by virtue of combining the force of man with the forces of nature brings together both aspects of the life-force in a being who can thus mediate between man and the origin of that force. By donning the mask in ritual to become that being, man could bring the otherwise destructive elemental forces under control so that they might aid in the maintenance of life by providing the rain in moderation so that the corn would grow and his own life would be maintained.

Thus, the were-jaguar mouth makes symbolic sense, but a glance at that mouth on Rain Gods C (pl. 6) and CJ (pl. 4) reveals a remarkable difference between image and reality; these were-jaguar mouths are toothless. The significance of this is made more apparent by the fact that although there are a great number of fanged were-jaguar mouths in Olmec art, Covarrubias and Coe and Joralemon have selected toothless images to represent the rain god. That this selection is correct is suggested, at least in the case of Rain God CJ, by the water associations of Monument 52. The lack of fangs might suggest visually the association with caves that would be somewhat more difficult to see were the mouths fanged, but the toothless mouth also carries other connotations linked in Mesoamerican thought to rain. The were-jaguar mask is often called a baby-faced mask, the reason for which can be seen in the more naturalistic faces that bear the same toothless were-jaguar mouth that we see here. In the context of the puffy cheeks and chubby facial configuration of those faces, the mouth looks like that of a pouting infant. When the face is found on a body with infantile features, as it often is, the designation seems even more apt. The child held by the Lord of Las Limas (pl. 3) is just such a figure and is, significantly, another primary image of Rain God CJ.

The association of infant and were-jaguar mouth inevitably brings to mind the ritual sacrifice of children to the rain god by both the Postclassic Maya and the peoples of central Mexico, a characteristic form of sacrifice that may well have a prototype in Olmec thought and ritual, as the seemingly lifeless body of the infant held by the Las Limas figure suggests. Most commentators explain this form of sacrifice in the terms suggested by Sahagún, as a form of sympathetic magic where-

by the tears of the children cause the rain, that is, "tears" of the gods, to fall.[69] And Thompson suggests that the rain gods "liked all things small";[70] their "helpers," the tlaloques or chacs , like today's chaneques , were thought of as dwarfs, though not children.[71] In addition to these connections between small children and rain, however, one might also see in this ritual the return of a child to the womb of the earth from which he has only recently emerged. Such an interpretation would accord with one of the means of sacrificial death—drowning in such a manner that the bodies never again rose to the surface—as well as the burial rather than cremation of the bodies of victims sacrificed in other ways to Tlaloc. The common Mesoamerican conception of the sacrificial victim as the bearer of a message to the gods would seem to support this interpretation, as would the symbolic identification of caves as both the womb of the earth and the source of rain and lightning. The lifeless body of the were-jaguar child held by the Las Limas figure whose infantile features are often found on Olmec figures would thus symbolically unite these diverse ideas.

These symbolic connections between the were-jaguar mouth and caves and infants help to explain the difficulty scholars have had in identifying the natural origin of the mouth. Though we feel certain that it is feline in origin, the natural form has been modified to suggest its symbolic multivocality by making visual reference to other rain-related symbols. The complexity of the symbolic structure lying behind the outward form is typical of the Mesoamerican way of constructing complex symbols by combining a number of symbolic details drawn from nature in a metaphoric, emphatically nonnatural structure. As we will explain in detail below, the life-force enters the world of man through transformation, and the construction of the mythic symbol illustrates that transformative process. The source of the water that nourishes natural life on the earthly plane is to be found in the world of the spirit, but the essence of spirit cannot be visualized. Hence the intermediary stage represented by the combination of natural features in a nonnatural, "spiritual" form. Through the mediation of that form—the symbolic were-jaguar mouth in this case—energy, in the form of rain, can flow from the world of the spirit to the world of man. Thus, the appearance of the toothless variant of the were-jaguar mouth on an Olmec mask, especially in conjunction with the cleft head, would connote fertility generally and rain specifically. It is especially interesting, then, that Coe and Joralemon and Covarrubias selected such masks as images of the Olmec rain god. Although neither explain in detail their reasons for associating the toothless mouth with rain, their remarkable familiarity with Mesoamerican religious symbols probably led them to do so intuitively. As we have shown, they had good reason to make that connection.

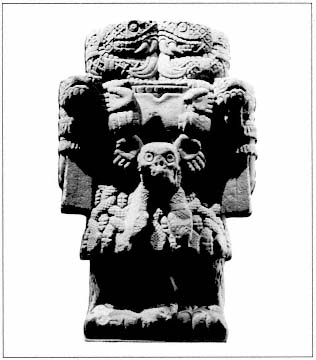

Although the similarities between these two faces indicate without a doubt that they are both concerned with the symbolic representation of forces associated with rain and fertility, there are important differences that indicate that Olmec symbolic art was not made up of a small number of static combinations of symbols endlessly repeated; it exhibits a large range of symbolic figures created by combining in different ways details drawn from the basic inventory of symbols. Thus, when viewing any collection of Olmec art, we are always involved in the fascination of theme and variation. Far removed in time and culture from the creators of this body of art, it is impossible for us to say with any precision what shades of meaning were conveyed to the Olmec cognoscenti by these variations, but we can say with certainty that such a body of symbolic art has the capacity to communicate sophisticated and complex spiritual ideas with precision. Such an art begins the heritage that came to fruition, for example, in the monumental Aztec Coatlicue (pl. 9) and on the lid of Pacal's sarcophagus at Palenque (pl. 10), both of which, as we will demonstrate, are complex symbolic structures that must be "read," item by item, if they are to reveal their profound meanings.

When we look again at the masks of the rain god, this time seeking variation, the variations we find form a fascinating pattern that holds constant the symbolic motifs of the toothless were-jaguar mouth at the bottom of the face and the cleft at the

Pl. 9.

Coatlicue, Tenochtitlán

(Museo Nacional de Antropologia, Mexico).

Pl. 10.

Relief carving on the cover of the sarcophagus of Pacal,

Temple of Inscriptions, Palenque (Photograph by Merle Greene Robertson

and Lee Hocker, reproduced by permission).

top while varying the treatment of the area between them. Taking care to deal only with masks representing mythological creatures—which can be distinguished from human representations with symbolic mouths by their frontal flatness, rectangular rather than ovoid shape, and symbolic cleft—we can see that the variation involves a progression from simple to complex and is accomplished by adding features to the basic mask. An excellent example of that basic mask can be seen in the headdress of a figure found at the summit of the volcano at San Martin Pajapán (pl. 11), one of the Tuxtla Mountains held sacred by the Olmecs. Its mountaintop placement, like that of rain god figures throughout Mesoamerican history, suggests clearly its function. The mask's almost square, flat shape, its pronounced cleft and symbolic mouth, and its almond-shaped eyes set at an angle to the horizontal line of the mask all contrast markedly with the human face below it and indicate clearly its symbolic nature. This is the symbol of the rain god—as identified by Coe and Joralemon, Covarrubias, and our own analysis—reduced to its essentials. The same mask also appears at La Venta in Monument 44, a head that is all that remains of a figure that must have been almost identical to that of San Martín Pajapán,[72] and on a small greenstone object from Ejido Ojoshal, Tabasco.[73]

Pl. 11.

Olmec Kneeling Figure,

San Martin Pajapán, Veracruz

(Museo de Antropologia de Xalapa).

The simplest variation on the basic theme involves the addition of eyebrows and changes in the shape of the eyes. The eyebrows are all the so-called flame eyebrows, and the mask Covarrubias identifies as the rain god, our Rain God C, displays them in one of their several variant forms. Masks displaying these eyebrows are commonly found on celts and votive axes carved to represent the figure of the rain god, but the same mask can also perhaps be seen on a sarcophagus found at La Venta.[74] The mask on the sarcophagus might have had a dangling, bifid tongue, a development of the rain god we will see clearly in all of the later rain gods of the Classic period, which would suggest a connection with the serpent. Such a connection may also be suggested by the eyebrows since, as several scholars have felt, these are probably better interpreted as feathers or plumes than as flames. If they are so interpreted, the composite mask reveals avian connotations and would suggest an Olmec

version—perhaps the original version—of the jaguar/bird/serpent symbolism associated with the lightning, wind, and rain of the storms through which water was provided by the gods for man. Just as there are variants of the flame eyebrows, there are also variants of eye shape in the masks with plume eyebrows. Some continue to display the almond-shaped eye of the basic mask, but others have rectangular, trough-shaped eyes, some of which are turned down in an L-shaped fashion at the outer edge. It is quite likely that the particular combination of eye and eyebrow—and all possible combinations seem to exist—meant something specific, now forever lost, to the Olmec priest.

At the succeeding levels of complexity, other items are added to the mask. The first of these is a headband with symbolic markings which covers whatever eyebrows the figure might be imagined to have. Perhaps attached to this headband are elaborate wavy ear coverings, which are long and narrow and similar to those often depicted in Aztec art, the design of which might well suggest water. Such a combination of headband and ear coverings is worn by the child held by the Las Limas figure (pl. 3), a primary image of Rain God CJ, as well as by an iconographically equivalent standing figure holding a child now in the Brooklyn Museum and can also be seen on several carved celts from the Olmec heartland. The final addition to the basic concept is that illustrated by Monument 52 from San Lorenzo (pl. 4), another primary image of Rain God CJ. In addition to the headband with ear coverings, this figure wears a headdress with a pair of presumably symbolic markings prominently displayed. Like the design on the ear coverings, these markings might also suggest water.[75] Since this image of Rain God CJ was found at the head of the system of ritual water channels at San Lorenzo, the symbols it carries likely relate to the gods' provision of water not by rain but directly from the earth in the manner of the cenotes and of underground springs bubbling to the surface.

Interestingly, however, a stone object from Tlacotepec, Guerrero, an area with caves but no cenotes, displays, in very different form, the same combination of mask and headdress. This suggests that the symbolic reference must be wider than one resting on an interpretation of the San Lorenzo figure. But whatever the precise meaning of each of the symbolic details of the many variants of the mask, it is clear that while all of the combinations refer to rain, each particular image has a different inflection symbolized by the individual combination of features drawn from the basic inventory. Perhaps each figure deals symbolically with a different part of what is, after all, quite a complex process, or perhaps one of the features—the mouth, for example—is significant enough to embody the basic meaning of any figure on which it appears.

But as we suggested at the outset of this lengthy discussion of the mask we call the Olmec rain god, that particular point of contact with the world of the spirit symbolized more than the provision of the life-maintaining rain. For the Olmecs, as for all the peoples of Mesoamerica who were to follow them, the mask that symbolically identified the rain god was simultaneously involved with the metaphorical delineation of the essentially sacred nature of what we would call profane power and thus demonstrated the intimate relationship between spiritual and worldly leadership which has always intrigued and puzzled students of the pre-Columbian Mesoamerican civilizations.[76] Although we will not attempt at this point to define precisely that relationship, it seems clear that the Olmecs believed, as did the Aztecs and all the civilizations between the two, that their rulers were provided by the gods and returned at death to the realm of the gods, the world of the spirit. In the exercise of profane power, these rulers spoke for the gods and provided an essentially spiritual order for the world of nature in which humanity was embedded. That spiritual function was symbolized in Olmec art by the were-jaguar mask, which also symbolized rain.

The origin of this fascinating three-way connection between rain, rulers, and jaguars cannot be discovered for us by archaeology, but it seems reasonable to suppose that that enduring link was forged in the Preceramic phase of the development of Mesoamerican culture, probably in the period of transition from the nomadic existence of hunting-gathering groups to the settled life associated with the beginnings of agriculture. It was at this time, perhaps, that the jaguar, the hunter's greatest adversary, became involved in Mesoamerican man's symbolization of the twin requirements for maintaining the communal life both based on and necessary for raising crops—a settled society and regularly timed rainfall. As we have demonstrated above, the were-jaguar mask metaphorically resolved the binary opposition between "wild" nature and the control necessary for the development of human culture. By uniting the equal opposites of the jaguar, the epitome of nature, and man, the epitome of culture, the were-jaguar mask provided the focal point for the ritual through which the gods' provision of rain could be harmonized with the needs of the crops that were to sustain human life and provide the basis for the existence of human culture.

Similarly, social harmony could be achieved through the rulership of a particular man sent by the gods to "take over the burden, . . . devote thyself to the great bundle, the great carrying frame, the governed."[77] In that sense, at least, the ruler is the equivalent of the rain. Both are sent by the gods, both are necessary parts of the framework within which the common man can sustain his life, and thus both are prerequisites for the life of

culture. The Quiché Maya creation myth embodied in the Popol Vuh is both fascinating and instructive in this regard since even though it is a post-Conquest document recording Postclassic beliefs, it clearly relates rain and rulers, sustenance and governance in its delineation of the creation of humanity, which is, of course, essentially a definition of what it means to be human. In the myth, man is finally created after three previous failures, two of which depict the newly created would-be man as incapable of attaining human status and relegate him to the status of "wild" animal. The meaning of these two failures is clear: true humanity can exist only in the context of culture, defined in the myth as the binary opposite of nature.

The second of those two cases—the wooden men who ultimately become monkeys—is especially intriguing since the myth takes care to differentiate between the forces of nature and those of culture. The wooden men are destroyed as humans and thus relegated to animal status by the forces of untamed nature—"The black rainstorm began, rain all day and all night. Into their houses came the animals, small and great"—and, separately, by the forces of culture—"Their faces were crushed by things of wood and stone. Everything spoke: their water jars, their tortilla griddles, their plates, their cooking pots, their dogs, their grinding stones, each and every thing crushed their faces."[78] The opposed forces of nature and culture act in destructive harmony on this occasion, but the myth makes clear that it is the task of human society, through ritual and the efforts of the ruler, to harmonize those forces, as Olmec art much earlier similarly harmonized the faces of jaguar and man in the metaphorical were-jaguar mask. This harmony, now constructive rather than destructive, is precisely the theme of the gods' fourth and final attempt to create man.

[They] sought and discovered what was needed for human flesh. It was only a short while before the sun, moon, and stars were to appear above the Makers and Modelers. Broken Place, Bitter Water Place is the name: the yellow corn, white corn came from there.

And these are the names of the animals who brought the food: fox, coyote, parrot, crow. There were four animals who brought the news of the ears of yellow corn and white corn. They were coming from over there at Broken Place, they showed the way to the break.

And this was when they found the staple foods. And these were the ingredients for the flesh of the human work, of the human design, and the water was for the blood. It became human blood and corn was also used by the Bearer, Begetter.

And so they were happy over the provisions of the good mountain, filled with sweet things, thick with yellow corn, white corn, and thick with pataxte and cacao, countless zapotes, anonas, jocotes, nances, matasanos, sweets—the rich foods filling up the citadel named Broken Place, Bitter Water Place. All the edible fruits were there; small staples, great staples, small plants, great plants. The way was shown by the animals.

And then the yellow corn and white corn were ground, and Xmucane did the grinding nine times. Corn was used, along with the water she rinsed her ands with, for the creation of grease; it became human fat when it was worked by the Bearer, Begetter, Sovereign Plumed Serpent as they are called.

After that they put it into words:

the making, the modeling of our first mother-father,

with yellow corn, white corn alone for the flesh,

food alone for the human legs and arms,

for our first fathers, the four human works.[79]

The creation of man is intimately connected here with the origins of agriculture, that is, with the "discovery" of corn at Broken Place. Broken Place, translated by Munro Edmonson as Cleft,[80] is symbolically the point at which man's sustenance, the corn, emerges from the world of the spirit into the natural world. This place-name in the Popol Vuh is thus the equivalent of the visual clefts found in the Postclassic Mixtec codices, and both symbols are related, as we have demonstrated above, to the symbolic cleft on the Olmec were-jaguar masks from which, of course, corn is often depicted emerging. But corn, as Mesoamerica well knew, is a cultivated plant, not a wild one, and the import of the myth in this regard is clear. Man exists in culture, not as a wild animal; the animals find the corn, but man is formed from it. Only within the context of culture can man make use of plants and water, his symbolic flesh and blood, to sustain his individual life and the life of the community without which truly human life would be impossible. And communities implied rulers to the Mesoamerican mind. The Popol Vuh makes this quite clear.

These are the names of the first people who were made and modeled.

This is the first person: Jaguar Quitze.

And now the second: Jaguar Night.

And now the third: Mahucutah.

And the fourth: True Jaguar.

And these are the names of our first mother- fathers.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

And then their wives and women came into being.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Celebrated Seahouse is the name of the wife of Jaguar Quitze.

Prawn House is the name of the wife of Jaguar Night.

Hummingbird House is the name of the wife of Mahucutah.

Macaw House is the name of the wife of True Jaguar.

So these are the names of their wives, who became ladies of rank, giving birth to the people of the tribes, small and great.

And this is our root, we who are the Quiché people.[81]

The mythical ancestors, the mother-fathers, the Lords of the Quiche, are the root of the Quiché people, their means of attachment to the source of their sustenance in the world of the spirit. These mythical beings are symbolically both male and female, matter and spirit, temporal and eternal, human and divine, and thus unite, precisely in the manner of the were-jaguar mask, the whole series of opposed categories that define god and man, categories that metaphorically find their meeting place in these "first people." These are the first rulers, the progenitors of and the models for all the Lords of the Quiché who are to follow them. Through their wives, they unite metaphorically the two aspects of the enveloping world of the spirit with the earthly plane on which man lives and on which they rule: Sea and Prawn suggest the watery underworld, equivalent in Maya thought to the cave, while Macaw and Hummingbird suggest the airy upper world. And all of them are married to and thus complement the Jaguar-three of the four Lords' names—the creature of the earth in this set of symbolic oppositions. The primary function of the ruler, then, is here defined through the metaphor of the three-layered cosmos fundamental to shamanistic thought as the uniting of matter and spirit.

Clifford Geertz explores this symbolic function in "Centers, Kings, and Charisma: Reflections on the Symbolics of Power":

At the political center of any complexly organized society ... there is both a governing elite and a set of symbolic forms expressing the fact that it is in truth governing. . . . [Such elites] justify their existence and order their actions in terms of a collection of stories, ceremonies, insignia, formalities, and appurtenances that they have either inherited or, in more revolutionary situations, invented. It is these—crowns and coronations, limousines and conferences—that mark the center as center and give what goes on there its aura of being not merely important but in some odd fashion connected with the way the world is built. The gravity of high politics and the solemnity of high worship spring from liker impulses than might first appear.[82]

When we discuss Olmec society, of course, crowns become headdresses and we must do without limousines, but the principle remains operative; here too, as early as 1200 B.C., we see carved in stone by Olmec sculptors the evidence of an elite at the center of things defining its position and function through "a set of symbolic forms" that thoroughly interweave "the gravity of high politics and the solemnity of high worship."

Strange as it might seem, the clearest expression of this fundamental theme of Olmec art appears not in the Olmec heartland on the Gulf coast but hundreds of miles away in the central highlands at Chalcatzingo, Morelos. Perhaps Grove is correct in contending that the art created on the Olmec "frontier," as he calls it, made graphically clear the ideas that "are abstracted in Gulf coast monuments" in order to instruct a populace not conversant with those concepts,[83] but whatever the reason, the thematic interweaving of high politics and high worship, of the rain god and the ruler, is nowhere more apparent than in Monument I at Chalcatzingo (pl. 7), a relief carving fittingly called El Rey by today's villagers. As we indicated above, Monument I depicts a figure holding a ceremonial bar seated within a stylized cave/jaguar mouth from which issue speech scrolls. On the one hand, the seated figure is clearly associated with the rain god by the stylized raindrops, identical to those falling from the clouds, decorating his costume and headdress and by his location within the mouth of the cave/jaguar, but, on the other hand, he is identified as a ruler by the ceremonial bar he holds and, perhaps, by the headdress he wears.

What might seem to be two conflicting thematic motifs in this relief can be resolved into one: we see here the Olmec identification of ruler and rain god. Monument I, according to Grove and Gillespie, "depicts a person seated within a cave, source of both water and supernatural power." That person, they believe, "was a revered ancestor rather than merely a generalized 'rain god."' But the location of the relief "above the site on the main rainwater channel," which would cause "the torrent of water rushing down the mountain" to appear "to come directly from this revered ancestor,"[84] and the evidence of the symbols on the relief suggest overwhelmingly that the "revered ancestor" or, perhaps, current ruler is to be equated metaphorically with the rain. The speech symbolized by the scrolls emanating from the cave mouth would seem to be either his speech or speech concerning him, and that speech is symbolically equated with the issue of the mouthlike rain clouds—the raindrops—with which his costume and headdress are also decorated. The ruler depicted here is symbolically equivalent to the rain, as is the "speech"—his rule—that issues from him, and thus from the gods. That speech sustains the life of the ruled as does the rain that gives life to the corn that nourishes man. While the relief was no doubt intended by its creators to commemorate a particular ruler

or to indicate their reverence for the supernatural power that provided the rain or, perhaps, to do both, its primary significance for us is to indicate the identification in the Olmec mind of those two motifs.

Another sculpture at Chalcatzingo, a fragment of a freestanding relief or stela, depicts a strikingly similar motif but in a form that relates it directly to the sculptures of the Olmec heartland we have discussed and helps, in the process, to clarify their meaning. This sculpture, Monument 13, depicts a seated or kneeling figure, remarkably similar in posture to the San Martin Pajapán figure (pl. 11), within a stylized cave/jaguar mouth identical to the empty cave/mouth of Monument 9 (pl. 8). The figure within this mouth suggests that the empty mouth of Monument 9 was occupied by a living figure, probably that of the ruler, in a ritual that legitimized his rule by relating it to the provision of rain. Both the rain and the ruler would thus be seen metaphorically as emanations of the world of the spirit. Furthermore, both Monuments 9 and 13 are frontal views of the mouth depicted in profile in Monument I, the mouth in which the seated figure fittingly designated El Rey is found, suggesting the importance of this theme in the art of Chalcatzingo.

But that theme is not restricted to Chalcatzingo and the Olmec frontier. It occurs with equal frequency, though somewhat more subtly, in the art of the Gulf coast Olmec heartland, as the striking similarity between the figure depicted in relief on Chalcatzingo's Monument 13 and the sculpted figure found atop the volcano of San Martin Pajapán indicates. Both are depicted in the same posture, a posture clearly indicated by the continuous curve described by the back, shoulders, and arms; both wear a headdress bent back and cleft; both have a mouth suggesting the were-jaguar configuration, but neither is an extreme version of that mouth; and both have their hands resting on a barlike object in front of them, an object that is probably a ceremonial bar and thus a symbolic indication of rulership. Furthermore, both are associated with a clearly symbolic version of the were-jaguar mouth: Monument 13's figure is seated within it and the San Martin Pajapán figure carries it in his headdress. Were Monument 13 not a fragment, we might see an even greater similarity because we would then know what the front of the seated figure's headdress looked like. But even without that knowledge, we can say the existing similarities are so striking as to demonstrate that the carver of the Chalcatzingo relief was depicting the same thematic motif, and that motif clearly relates rulership to rain.

That relationship can also be seen in the complex of symbols depicted in several variant forms on the monumental sculptures called altars, but which more likely served as thrones, found throughout the heartland and at Chalcatzingo and depicted in a painting on the cliff face above a cave-shrine at Oxtotitlán, Guerrero. These "altars" are massive rectangular tablelike forms with tops extending beyond large pedestal bases. Altar 4 from La Venta (pl. 12), the most fascinating of them from our point of view in this discussion, depicts on the face of its pedestal, below the protruding ledge of its top, a figure in high relief wearing a headdress, cape, and pectoral ornament. He is seated crosslegged within the stylized mouth of a were-jaguar, a mouth remarkably similar to the mouths on the Chalcatzingo reliefs. Above the mouth on the face of the ledge appears the upper jaw, fanged and decorated with the St. Andrew's cross, and the eyes, with a cleft between them, of the were-jaguar. Interestingly, though the body of the emerging figure is quite realistically human, the face, though now mutilated, seems also to suggest the were-jaguar. Bent forward slightly, the figure grasps a rope that runs along the base of the altar and is tied to realistically depicted human figures on either side. Those familiar with later Maya symbolism would be inclined to see the figures on the sides as captives suggesting the dominance of the lord seated in the niche.[85] But the figures on the sides are not bound, as captives typically are in Maya art, and may symbolize kinship ties resulting in alliances with the domains of other lords[86] or the common Maya theme of accession. In any case, it seems clear that the symbolic meaning of the rope is related in some way to earthly rulership and equally clear from the altar as a whole that rulership is to be thought of as fundamentally connected with the rain suggested by the were-jaguar/cave mouth motif. That this complex of ideas was also present at the Olmec site of San Lorenzo is indicated by Monument 14, an altar that is now heavily mutilated but which seems to have been virtually identical to La Venta Altar 4.

Other Gulf coast altars, La Venta Altars 2 and 5 and San Lorenzo Monument 20, express the same symbolic meaning in a different way by depicting a seated figure in a cave/mouth niche holding a seemingly lifeless infant. The infant is probably always the were-jaguar figure we have called Rain God CJ[87] so that the symbolic motif is identical to that of the Lord of Las Limas (pl. 3). Altar 5 of La Venta is the least mutilated of this group, and it, like Altar 4, bears figures on the sides (pl. 13); each of the figures wears an elaborate headdress and holds a were-jaguar infant or dwarf, but one who is very much alive in contrast to the lifeless infant held by the central figure. That contrast might very well suggest that the central infant represents a sacrifice, an offering to the rain god, while the four infants or dwarves on the sides represent the quadripartite helpers of the rain god—the Olmec prototype of the later chacs of the Maya or tlaloques of central Mexico. The elaborate headdresses of the

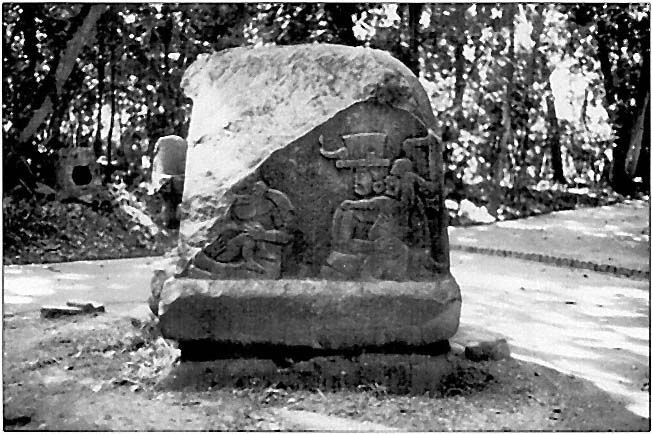

Pl. 12.

Altar 4, La Venta (Parque Museo de La Venta).

Pl. 13.

Altar 5, La Venta, side view (Parque Museo de La Venta).

figures holding the infants as well as their realistic features, in contrast with the were-jaguar features of the infants or dwarfs, suggest that they are depictions of past or present rulers, thus tying rain and rulership together in still another fashion. And just as the rope on Altar 4 may represent kinship ties, the infant on Altar 5 may also suggest "the basic concept of royal descent and lineage."[88] The Olmec altars, then, symbolically link Olmec rulers to the provision of rain from the realm of the spirit, the entrance to which is represented by the niche in the altar symbolizing simultaneously the were-jaguar mouth and the cave. Thus, in an almost literal sense, the altars were "masks" placed on the earth to allow the ritual entrance into the world of the spirit from which the power wielded by the temporal ruler must ultimately flow. That power was legitimized by virtue of its emergence, through the mask, from the world of the spirit.