GROUP-WIDE ACTIVITIES: THE SYMBOLS AND CEREMONIES OF ALLIANCE

Symbolically significant group-wide activities within the keiretsu serve to establish a framework within which group interaction can take place. These both establish a sense of coherent identity for group members and, just as important, position the group as a whole within the larger business community. The presidents' council represents one important symbolic framework within which group cohesion is created, but in addition, each of the keiretsu has moved into a variety of industrial, public-relations, and social activities that bring together group companies as a collective social unit.

The Symbolic Role of Industrial Projects

Where joint projects involving group firms expand to include most or all of the core companies in the group, their significance extends beyond a smaller subset of companies to take in the group as a whole. Among the twenty-five projects involving the Sumitomo group cited in Keiretsu no kenkyu for 1982-84, nearly half involved more than three group companies, and some brought together most or all of the core group mem-

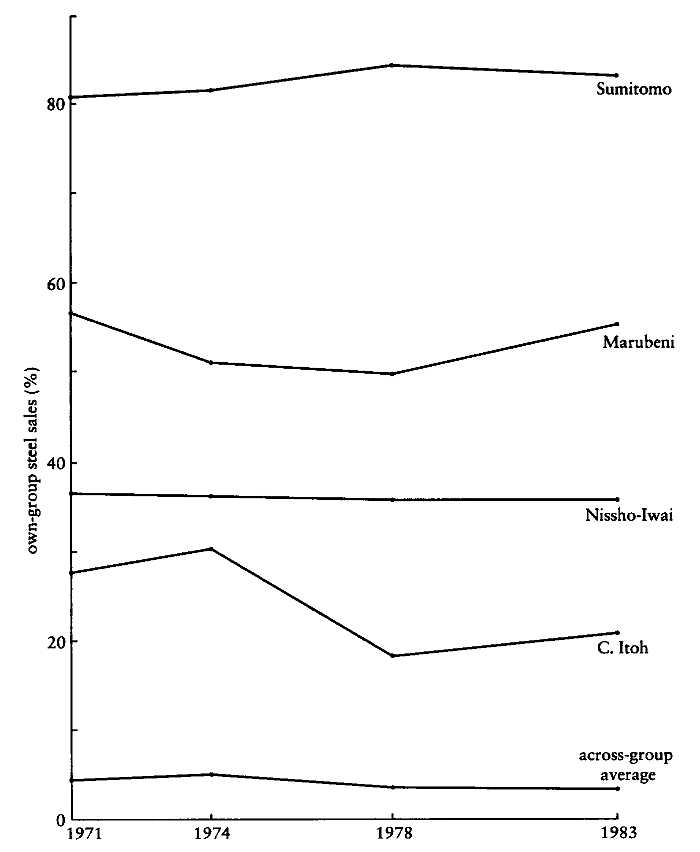

Fig. 4.10. Durability of Sogo Shosha-Steel Company Transactions.

Source: Sogo shosha nenkan (1972, 1975, 1980, 1985).

bers. While the symbolic content of group-wide activities is perhaps more readily apparent in other group activities, even ostensibly instrumental business projects such as joint industrial investments often appear to be more important for establishing the position of the group within the larger business community than for pursuing their immediate economic interests.

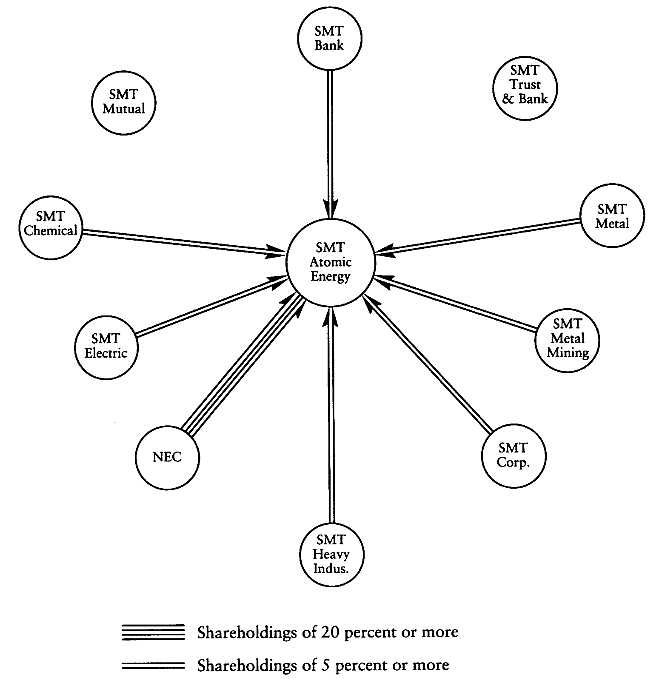

The evidence for this is found in the fact that group-wide industrial projects, even in major industries such as atomic energy and overseas petroleum development, have nearly all remained limited in size and scope. Within the Sumitomo group, for example, the largest joint project, Sumitomo Atomic Energy, employs only thirty people, and its asset value (¥2.3 billion) puts it at well under 1 percent of the total asset value of any of its core investing Sumitomo companies (data from Industrial Groupings in Japan, 1982). Rather than grow into large operations in their own right or produce breakthrough technologies, group industrial projects tend to serve as a focus for the resources and technologies already existing among group firms.

The symbolic importance of collaborative projects in the status competition among groups is further evident in the way in which group projects have tended to spring up almost simultaneously in highly visible and currently popular fields. This is seen in the project waves that marked the period 1957-73, shown for the three former zaibatsu groups in Table 4.8.

The first wave of group projects began in the late 1950s, when Japan was seeking alternatives to imported oil as a source of energy and each of the three groups moved into the field of atomic power. This was an important event in the postwar history of the groups, as it was the first time since the dissolution that the companies involved had cooperated as a group on a systematic task. The intragroup ownership structure for Sumitomo's atomic energy project as of 1980 is shown in Figure 4.11.

After a series of smaller ventures in the information industries in the late 1960s, the groups moved into the next major wave in the early 1970s in domestic and overseas development projects. Mitsubishi was the leader this time, starting Mitsubishi Development in 1970 to celebrate its centennial anniversary, with thirty-two companies participating. This was a decade of heady growth for Japan, as seen in then Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei's plan to "remodel the Japanese archipelago," with the resulting need to build industrial centers in sparsely settled areas of Japan. With the stimulus of economic potential and, perhaps more important, the challenge posed by the Mitsubishi group, the Mitsui and Sumitomo groups started projects the following year with thirty-four and fifteen companies, respectively. Among the bank groups, companies affiliated with the old Dai-Ichi Bank were the first to enter, joining Mitsubishi in the same year with a twenty-seven-company project. The Fuji and Sanwa groups started their own projects in 1972 with twenty-eight and twenty-nine companies, respectively.

TABLE 4.8. PROJECT WAVES INVOLVING THE MITSUBISHI, MITSUI, | ||||

Year | (Group) | Project Name | Capitalization | Share Held |

1957 | (SMT) | Sumitomo Atomic Energy | 1,590 | 80.0% |

1958 | (MTB) | Mitsubishi Atomic Power Inc. | 4,500 | 97.9% |

1958 | (MTS) | Japan Atomic Energy | 3,250 | 72.4% |

1967 | (MTS) | Mitsui Information Devt. | 500 | 61.0% |

1969 | (SMT) | Japan Information Service | 600 | 95.0% |

1970 | (MTB) | Mitsubishi Research Inst. | 1,000 | 61.0% |

1971 | (SMT) | Sumitomo Business Consulting | 200 | 44.5% |

1970 | (MTB) | Mitsubishi Development | 2,500 | 87.8% |

1971 | (MTS) | Mitsui City Development | 1,000 | 63.0% |

1971 | (SMT) | Sumitomo City Development | 1,000 | 100.0% |

1967 | (MTB) | Western Japan Petro. Devt. | 13,600 | 56.8% |

1968 | (MTB) | Middle East Petroleum | 7,570 | 41.2% |

1969 | (SMT) | Sabah Overseas Petroleum | 2,780 | 42.4% |

1969 | (MTS) | Mitsui Petroleum Devt. | 6,980 | 74.1% |

1972 | (MTB) | Mitsubishi Petroleum Devt. | 7,000 | 81.1% |

1973 | (SMT) | Sumitomo Oil Development | 5,000 | 78.9% |

SOURCE : Futatsugi (1976, p. 64). Notes: MTB refers m the Mitsubishi group, MTS to the Mitsui group, and SMT m the Sumitomo group. | ||||

Fig. 4.11. Sumitomo Atomic Energy Industry, Ltd.

Source: Data from Industrial Groupings in Japan (1982).

Note: SMT = Sumitomo.

Large-scale overseas petroleum projects were also highly visible during this period, but were unusual in that they also brought in a number of important nongroup companies. Mitsui began in 1967 with its Iranian petroleum complex, which involved its trading firm, Mitsui and Co., as main sponsor (holding 45 percent of equity) and also included Mitsui Toatsu and Mitsui Petrochemicals, as well as the outside firms of Japan Synthetic Rubber and Toyo Soda Manufacturing. Mitsubishi's project in Saudi Arabia began with Mitsubishi Corporation and brought in other group companies (most visibly Mitsubishi Petrochemicals). However, they were able to position themselves as a national project, receiving

45 percent of capital in Overseas Economic Assistance money from the Japanese government, by bringing in outside steel, automobile, and other non-Mitsubishi companies. In total fifty-nine firms were involved. Sumitomo's oil project in Malaysia brought in outside companies for the same reason as Mitsubishi's-in order to qualify for government assistance as a "national project."

The 1980s have seen the proliferation of projects in all six major keiretsu in new and high technology industries, particularly in what the Japanese business community has called the "C&C industries"-computers and communications. Mitsubishi formed the Mitsubishi C&C Kenkyu-kai in 1981, a study team bringing together forty Mitsubishi companies to develop technologies related to high-level data transmission that will link firms through electronic firm banking, producer-sales agent data exchanges, and other forms of interfirm communication. Mitsui followed in 1982 with the Mitsui Joho Shisutemu Kyogi-kai, with thirty-nine Mitsui companies participating in projects in value-added networks and other telecommunications-related technological fields. In 1983 ten more firms were added, including several large firms that maintain close connections with the Mitsui group but do not participate in its council-Sony, Ito Yokado, and Tokyo Broadcasting System.

The Mitsubishi and Mitsui groups have escalated the baffle by introducing foreign competitors into their alliances. This began with a tie-up involving Mitsubishi Corporation, Cosmo 80 (a Japanese software company), and IBM in a venture business in the computer software and communications field. The Mitsui group followed by establishing an arrangement with AT&T to introduce the latter's large-scale enhanced information networks into Japan. Recently, IBM's relationship with Mitsubishi has been extended to the formation of a partnership with Mitsubishi Electric in which IBM Japan will supply the key technologies of some of its most advanced mainframe computers in return for Mitsubishi sponsorship of IBM sales in Japan (Japan Times, April 28, 1991).

The implications of these trends are important in at least two ways. First, they suggest that foreign firms positioning themselves in the Japanese market are also subject to the same dynamics of alliance formation that affect the positions of Japanese firms. This must therefore become an element in foreign firms' market entry strategies. Second, the network technologies themselves will undoubtedly affect the nature of interfirm relationships, since decisions about the organizations with which one establishes information networks will set the framework within which other ongoing business transactions are carried out. If, for example,

direct orders can be made between companies by computer, a key factor in determining sales patterns will be the presence or absence of computer and data transmission connections between firms. Choices about communications networks will become an increasingly important part of firms' alliance strategies.

Public Relations and Social Activities

The importance of collaborative projects in symbolizing group coherence is dearly seen in the groups' public relations activities. Osaka's Expo '70 attracted pavilions for the five major keiretsu existing at the time as well as for several vertical groups. These pavilions brought together not just core firms but the broader group, including satellites of core companies and companies in the group periphery. Altogether, Sumitomo's pavilion involved forty-seven companies, Mitsubishi's thirty-five, Mitsui's thirty-two, Fuyo's thirty-six, and Sanwa's thirty-two (Miyazaki, 1976, p. 229). These five groups were also included more recently at the 1985 Tsukuba Science and Technology Exposition. Each had its own pavilion, the contents of which involved displaying various technologies and products of member firms, as well as presenting the group as a whole as a progressive force for the future.[27]

Group projects have even moved into the social sphere, including facilitating marriages among employees of different member companies through group-wide marriage advisory centers, or kekkon sodan-jo. In the case of the Fuji group, for example, prospective brides and grooms go to a special office with small rooms and red velvet sofas and fill out questionnaires about their lives, interests, and requirements for a mate. Applicants pay a service charge for registration and an additional charge if the registrant gets engaged.[28]

Perhaps the most elaborate set of activities is found in the Sanwa group, now formalized into a separately chartered organization called the Midori-kai and involving an extended membership of 154 corporations. The functions of this association are summarized in the Oriental Economist (September 1982) as follows:

Twice a year the Midori Kai sponsors a special invitation bazaar for discount sale of a wide range of merchandise to member-company employees and their dependents. Tennis tournaments, baseball games, and other sports events are organized as are competitions in go, shogi (Japanese chess) and other indoor pastimes. There are also study groups, art classes, and cultural and topical

seminars as well as beer parties and other recreational gatherings. Also maintained are a health care center, clinics, a wedding hall and dining rooms for nuptials and various social functions. In short, the Midori Kai takes care of virtually all needs in food, clothing and housing as well as in health, medical care, travel, insurance, consumer credit, leisure, and recreation. Taking advantage of the services and facilities offered are close on a million people when employee families are included. . .. The Midori Kai projects the Sanwa image of caring for people and their immediate needs.

The Fuji group also maintains a set of facilities for group-wide use, though it is not on the scale of Sanwa's. At the "F-kai," group-wide events include sports tournaments and beer parties where the middle-level managements of group firms can interact. Among upper-level executives, the prime forum for social interaction, apart from the golf course, is typically the hostess club. Accordingly, Fuji group companies have invested together in a downtown Tokyo club dubbed the Fuyo Ginza Club.

The keiretsu also have their own group publications, of which Sumitomo's English-language magazine is representative. Called the Sumitomo Quarterly, a typical issue includes interviews with one or two executives in Sumitomo group companies, news of various group projects, events involving individual group companies such as new technology development, as well as several articles of more general interest. The front cover of one issue, which shows the outside of Sumitomo's 1985 Tsukuba pavilion, is reproduced in Figure 4.12. Other publications are also issued by the Sumitomo group, including the group's official history and a book of general information on group companies. All of these are published through the group's trading company, Sumitomo Corporation.