Tribes of Arunachal Pradesh

The tribal populations of Northeast India, which will be discussed in chapter 11, belong racially, linguistically, and culturally to a sphere totally different from that of all the aboriginal tribes of Peninsular India, and their present political situation contrasts fundamentally with that of tribals in states such as Andhra Pradesh.

Arunachal Pradesh, the union territory previously known as the North East Frontier Agency, is a mountainous region extending between the Brahmaputra Valley, whose eastern part it encloses like a horseshoe, Tibet to the north, Burma to the east, and Bhutan to the west. With the Tibetan region of China it has a common frontier, from the Bhutan border eastward to the tri-junction of India, Burma, and China in the extreme northeast. The border with Tibet/China is about 1,000 kilometers long and runs along some of the highest mountains of the eastern Himalayas. Arunachal Pradesh occupies an area of 81,436 square kilometers (31,438 square miles), and the population at the time of the 1971 census—the latest available enumeration—was 467,511. This means that the average density of population per square kilometer is only 6, whereas the comparable figure for the whole of India is 178 and that for Assam, 153.

Arunachal Pradesh comprises ethnic groups of great cultural diversity, but in many respects there is an overall uniformity. All tribes are

of basically Mongoloid stock, and they all speak Tibeto-Burman languages. Many of these languages are not mutually understandable, but there are also large areas within which people can communicate by each speaking his own language, which is more or less understood by those speaking other dialects. British administration extended over only a small part of the present territory of Arunachal Pradesh, and the populations of large areas lived then in virtual isolation, although those of the northern border areas maintained occasional trade contacts with Tibet, while those of the foothills were dependent on some barter trade with Assam. Since 1947 strenuous efforts have been made to bring the entire territory under the effective administration of the Government of India, and in 1978 a democratic form of government based on universal franchise was introduced. Today Arunachal Pradesh has a legislative assembly and a cabinet of ministers consisting of members of this assembly.

The following ethnographic notes relate only to communities discussed in chapter 11, for in this context a description of all the tribal groups would serve no useful purpose.

Nishis

A large population of closely related tribal groups extends over the southern and western part of the Subansiri District and across its western border into the Kameng District. As long as little was known about the people of these districts, the members of this population were called Daflas, a name coined by the Assamese of the adjoining plains, which has the somewhat derogatory connotation "wild man." With the development of contacts between the people of the hills and those of the Brahmaputra Valley and particularly with the spread of education among the tribesmen, this term appeared objectionable to the people concerned, and they insisted on being referred to as Nishi, a term which is derived from the word Ni meaning "man." Today the name Dafla has been discarded and Nishi (or in relation to some groups Nishang) is used in conversation and all official publications, though some Assamese persist in their old habit of referring to the hillmen as Daflas. In the 1971 census 33,805 Nishis, 15,462 Nishangs, and 8,174 Hill Miris were counted, but it is not clear what criteria were used to distinguish between Nishis and Nishangs.

According to tribal tradition all Nishis are descended from one mythical ancestor by name of Takr, and it is also believed that his sons became the forefathers of three branches of the tribe, respectively known as Dopum, Dodum, and Dol. Each of these branches is divided into a number of phratries, which are exogamous units subdivided into several named clans. This system is spread over an extensive area,

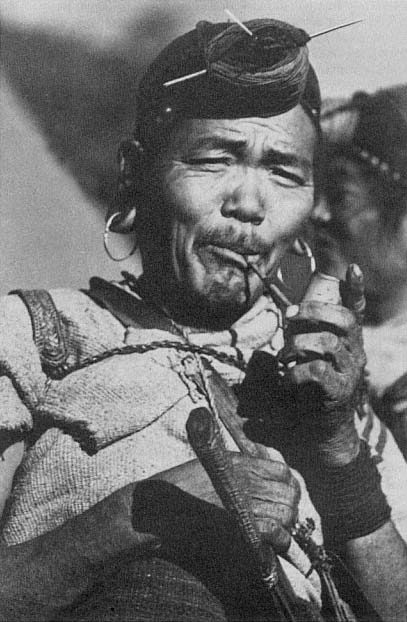

Nishi man of Jorum village. Cane hats and hair-knots pierced by a brass pin are

part of the traditional Nishi attire, and served as protection as well as decoration.

Miri woman of the Raga Circle. The disks worn in the ear-lobes are made of silver;

the necklaces are partly of glass beads and partly of more valuable stone beads.

Nishi war leader speaking during peace negotiations to end a long-standing

feud in 1944.

and there are few men whose knowledge of its ramifications extends further than their own phratry. Though the Nishis' mobility is high and there is evidence of extensive migrations, it appears that the three major branches and also some of the phratries had at one time a regional dimension.

But neither phratries nor clans are political units, nor in traditional Nishi society did the members of a village cooperate in the pursuance of political aims. We shall see in chapter 11 that in recent years there have been considerable changes in the system of social control, but in the conditions which prevailed until well into the 1940s (in many remote areas, into the 1950s and even the 1960s) the primary social unit was the household. Most Nishis lived and still live in long-houses comprising several families. It is only the members of such a giant household who have the duty to support each other in any dispute with outside adversaries, for Nishis lacked a tribal organization capable of maintaining law and order.

The instability of Nishi society was linked with the system of land tenure. As no one had individual rights to land and the inhabitants of a settlement were free to cultivate wherever they chose, wealth could not be invested in land, and movable possessions, be they cattle or valuables, were liable to fall into the hands of powerful opponents. A

Nishi men discussing the terms of a peace settlement.

concomitant of the general insecurity and frequency of armed hostilities was the distinction between free men and slaves. The latter were mainly people captured in war and either kept by their captors or sold. Their children became members of their owner's clan, but their status was that of dependents rather than slaves, and in time they could gain their freedom and acquire property. Thus there existed among Nishis no permanent slave class, barred for all time from a rise in social status.

Like most other tribes of Arunachal Pradesh, the Nishis were traditionally slash-and-burn cultivators. They cleared the forested slopes lying at altitudes between one thousand and six thousand feet and grew rice, millet, and pulses on these hill fields. Hoe and digging stick are their principal agricultural implements, and though they breed cattle, particularly mithan (Bos frontalis) , they use neither the plough nor any form of animal traction. In recent years, however, the cultivation of rice on permanent, irrigated fields has been introduced in many villages possessing some level land, and this change in agricultural methods has caused economic as well as social changes.

Barely distinguishable from the Nishis of the western part of Subansiri District is a tribal group about 8,200 strong officially referred to as Hill Miris, which is settled in the hills to both sides of the lower

course of the Kamla River. The two groups merge and overlap, and any line drawn between them would be entirely arbitrary, for there is no bar to intermarriage and many so-called Hill Miris describe themselves as Nishis when speaking their own language.

Equally blurred is the distinction between the Nishis of the upper Kamla Valley and the tribes living to the north of that area and spreading into the Sipi Valley and that of the upper Subansiri. They are usually referred to as Tagin, but as so far no anthropological research has been done among this ethnic group, little information of an ethnographic nature is available.

In the Kameng District the people identical with the Nishis of the Subansiri District but separated from them by a high though not impassable mountain range are known as Bangni. Their life-style is similar to that of the Subansiri Nishis, and in the days before the establishment of Indian administrative control they were as warlike as their eastern fellow-tribesmen and used to terrorize the less martial local tribes.

Bibliography

Bower, Ursula Graham. The Hidden Land. London, 1953.

Fürer-Haimendorf, C. von. Ethnographic Notes on the Tribes of the Subansiri Region. Shillong, 1947.

——. Himalayan Barbary. London, 1955.

Pandey, B. B. The Hill Miri. Shillong, 1947.

Shukla, B. K. The Daflas of the Subansiri Region. Shillong, 1959.

Apa Tanis

Whereas Nishis, Hill Miris, and other related groups merge imperceptibly one into the other, there is one people, known as Apa Tani, which constitutes a separate endogamous community with its own territory, language, customs, and traditions, and an economy fundamentally different from that of all other tribes of Arunachal Pradesh. In a single valley with an area of approximately fifty-two square kilometers, close to 13,000 Apa Tanis live in seven villages ranging in size from 160 to 1,000 houses. The fact that roughly 300 tribal people can make a living on one square kilometer would be unusual anywhere among primitive subsistence cultivators dependent on their own resources, but in an area where no other tribe had until recently any idea of intensive cultivation, the achievement of the Apa Tanis is truly astonishing. Both Nishis and Apa Tanis are agriculturists, but their systems of cultivation differ fundamentally. While the Nishi slash-and-burn cultivator seldom tills a piece of land more than two or three years in succession, the Apa Tani tends every square yard of his land

with loving care and the greatest ingenuity. Until the economic revolution of recent years, land was to him the source and essence of all wealth, and only the possession of land gave a man material independence. All cultivated land is jealously guarded property, and good irrigated fields fetch prices that in the plains of Assam would be considered fantastic. Rice cultivated on irrigated terraced fields is the Apa Tani's main crop, but on dry land millet, maize, potatoes, and vegetables are grown. All cultivation is done with iron hoes, digging sticks, and wooden batons, for not only were ploughs unknown in the past, they also failed to gain acceptance in recent years when Apa Tanis eagerly took to bicycles and other products of modern technology.

While most Nishis live in dispersed settlements, the Apa Tanis dwell in crowded villages where hundreds of houses stand eave to eave in long streets and narrow lanes. The villages are divided into wards, and each of these contains several exogamous clans. The villages are administered by councils of elders, but there has never been any overall authority controlling the entire tribal community or determining its relations with neighbouring Nishi villages.

A characteristic feature of Apa Tani society is its rigid stratification. There are two classes differing in status: an upper class whose members own the larger part of the land and wield political power in clan and village, and a lower class which used to consist of free men owning their own land as well as of domestic slaves. The latter have now been freed, but the endogamy of the classes persists, though nowadays it is occasionally breached.

Priests and shamans maintain communications with the world of gods and spirits, whom they propitiate with animal sacrifices and food offerings. There is a strong belief in an underworld, where the dead lead a life resembling in all details life on earth.

Bibliography

Bower, Ursula Graham. The Hidden Land. London, 1953.

Fürer-Haimendorf, C. von. The Apa Tanis and Their Neighbours. London, 1962.

——. Morals and Merit--A Study of Values and Social Controls in South Asian Societies. London, 1967.

——. A Himalayan Tribe: From Cattle to Cash. Berkeley and Los Angeles/New Delhi, 1980.

Khovas

The Khovas are a small tribe of slash-and-burn cultivators inhabiting ten villages in the Bomdila Circle of Kameng District. In their own

language they call themselves Bugun, but this name is not used by any of their neighbours. Their social organization is based on a system of exogamous clans distributed over all the ten villages. The tribe is strictly endogamous, and there is no intermarriage with any neighbouring tribe, such as the Akas and Mijis, whose life-style is similar, or the Sherdukpens, with whom the Khovas have long-standing ritual and economic relations. Though the Khovas' traditional religion consists of the worship of numerous deities and nature spirits, which involves sacrifices of cattle, they are now influenced by Tibetan Buddhism and have begun to employ lamas for the performance of rituals. The Khovas used to have trade relations with Monpas as long as the latter were in a position to trade with Tibet. In the 1971 census only 703 Khovas were returned, but this may be an underestimate due to the fact that the small community is known under different names.

Bibliography

Elwin, Verrier. Democracy in Nefa. Shillong, 1965. Pp. 77-80.

Sherdukpens

The small tribe of Sherdukpens, numbering about 1,600 souls, inhabits a single valley of the Kameng District, where most of the population is concentrated in the two principal settlements of Rupa and Shergaon, each of which has several satellite villages. In their own language the Sherdukpens refer to themselves as Senji-Thonji, but the neighbouring Monpas call them Sherdukpen, and this name has been adopted in official records. According to local tradition the Sherdukpens are the descendants of a Tibetan prince and his followers who came originally from Beyalung in Tibet and first settled in Bhut, a village near Dirang Dzong, where the ruins of their first fort are still standing. Like Apa Tani society the Sherdukpen community is divided into two unequal and endogamous classes, known as Thong and Tsao, each of which comprises several exogamous clans. The Thong class is supposed to be descended from the legendary princely ancestor, whereas the inferior Tsao class stems from his attendants who immigrated at the same time. The Sherdukpens have long-standing political and trade relations with the plains people of Assam, and in one locality on the fringe of the plains there is still an area of 103 acres which is under the control of Rupa and serves as the site of an annual festival celebrated jointly by Sherdukpens and Assamese. Similarly, people from Assam send gifts to support the celebration of a festival at Rupa. The tribal god worshipped at this festival has no connection with Buddhism, and the priests ministering at the rites are local men elected by the people of Rupa. Yet, there is in Rupa a large Mahayana gompa deco-

rated in a style influenced by Bhutanese and Tibetan prototypes. Like many populations on the periphery of the Tibetan culture sphere, the Sherdukpens practise two religions: an old tribal cult as well as Mahayana Buddhism. The Buddhist rituals are performed by lamas who are of Bhutanese origin or have been trained in Bhutan.

The Sherdukpens have some level land which they plough, using crossbreeds of mithan and ordinary cattle for traction. On hill slopes they practise shifting cultivation in the same way as Khovas and many Monpas.

Bibliography

Sharma, R. R. P. The Sherdukpens. Shillong, 1961.

Monpas

All along the northern border of Arunachal Pradesh there are populations influenced by Tibetan culture or of Tibetan origin. In Kameng District, a population of 23,319 Monpas was returned in the 1971 census, but it seems that 1,716 Dirang Monpas, 1,046 Lish Monpas, and 826 Tawang Monpas listed separately are not included in that number. However this may be, in the Bomdila and Tawang subdivisions Monpas form the majority of the population. All of them speak languages akin to Tibetan, but not all of the local dialects are mutually understandable. Yet, culturally the various groups of Monpas have much in common. They differ fundamentally from such non-Buddhist tribes as Bangnis (as the Nishis are called in Kameng), Akas, Mijis, and Khovas, but share the Buddhist heritage of the Sherdukpens.

Most Monpas are high-altitude dwellers, and their economy has far more in common with that of such Himalayan populations as the northern Bhutanese or most Bhotias of Nepal then with the economy of most tribal groups in Arunachal Pradesh. For the cultivation of their level land they use ploughs and bullocks or yak-hybrids, though here and there they also practise slash-and-burn cultivation on hill slopes too steep for ploughing. Barley, wheat, and buckwheat are their main crops, though in sheltered valleys at an altitude below eight thousand feet rice is also grown. Monpa society is divided into several strata of different social status, but there is no developed system of exogamous clans comparable to that of Nishis, Khovas, or Sherdukpens.

Buddhist beliefs and traditions dominate cultural life, and monasteries and nunneries play an important role in the fabric of Monpa society. But side by side with Buddhist institutions there persists a cult of tribal deities conducted by priests who are openly described as representing an old religion related to the Tibetan pre-Buddhist Bon faith.

It is this coexistence of Buddhism with tribal religions which suggests the possibility of a fertilization of local cults by the more sophisticated ideology of Mahayana Buddhism, which was at one time the mainspring of Tibetan civilization.

Anthropologists concerned with India have for some time debated the problem of the distinction between autochthonous tribal groups and Hindu castes. Those speaking of a tribe-caste continuum hold the view that it is impractical to draw a sharp line between tribes and castes, whereas others feel confident of their ability to decide in concrete cases whether a given community should be classified as a tribe or a caste.

The notification[1] of tribal groups as "scheduled tribes" by the Indian Parliament clarifies, in most cases at least, the legal position. Yet there remain borderline cases. Political reasons may motivate a state government to include a particular community in the list of scheduled tribes, whereas in a neighbouring state more resistant to pressure groups the same community may not be notified as a scheduled tribe, and hence may not enjoy the privileges granted to kinsmen on the other side of the state boundary (see chapter 8). Insofar as the tribes included in the foregoing list are concerned, there can be little doubt that they deserve the politically advantageous classification of scheduled tribes.

In Arunachal Pradesh the notification of an ethnic group as a scheduled tribe is not of great relevance because in this union territory tribals constitute the majority of the population and power lies in their hands. It becomes important only for those tribesmen who pursue studies or a career outside Arunachal Pradesh and benefit from the reservation of a percentage of places in universities as well as of jobs in government service for members of notified tribal communities. In Andhra Pradesh, the autochthons are now a minority, even in areas where not long ago they constituted the main population, and the privileges granted to scheduled tribes play a vital role in their struggle for economic and cultural survival.

[1] Notification is a legal term used in India—as in other previously British territories—for the promulgation of laws and government ordinances in the official gazette. Tribes notified as belonging to the "scheduled tribes" and notified tribal areas are those whose special legal status was established by a "notification" in the government gazette.