THREE

THE PAST IN THE PRESENT

6

The Inheritance of the Neighborhoods

Processing migrants by class, race, and religion; four-part cultures

One of the Remarkable Qualities of the American metropolis is the cultural consensus which runs throughout its neighborhoods. For cities so vast, composed as they always have been of migrants from every circumstance of life, the presence of this consensus is an extraordinary historical event well worth understanding for its own sake. Yet the cultural uniformity of the American metropolis, a legacy from the past, has further significance in that it holds the potential of great service to the future. It is the best foundation we have upon which to build powerful and sustained urban plans and policies.

Current social science studies show that our cultural consensus runs far deeper than the common factors of television, automobiles, and the consumerism of the mass media. It is rooted in the behavior and aspirations of millions of American families, rich and poor, black and white. In the everyday behavior of urban families can be seen the commitment to the basic values of an equalitarian private competitive life which is manifested in a common residential style of loyalty to relatives, friendly visiting of neighbors, pressing for the education of children, concern for family health, the use of housing and neighborhoods as the expressions of family status, high tolerance for interfaith marriage, and an openness of membership in churches and other local institutions. The frequent complaints against our urban style of living, the income striving, lack of close communities, the rapid movement of families from place to place,

and the exclusionary tactics of many suburbs are but the concomitants of this same consensus.

Working against this common culture, both its openness and its near-universal private family expectations, are two deeply ingrained attitudes which are endlessly reinforced throughout the metropolis: the tradition of white racism and the differential rewards of capitalism. The former poisons every neighborhood and institution, the latter segregates the city into clusters of families of similar class attainment and delivers the power and destiny of the modes of urban growth into the hands of the well-to-do. By their overwhelming purchasing power and control of most of the political, economic, and social institutions of the city, the upper income groups always have controlled and still do control the allocation of the city's resources and the determination of its patterns of development.

Thus today we do not face an urban crisis brought on by some sudden disaster; we suffer from a heightening of a chronic urban disease. Our situation deserves to be called a disease since most of its symptoms—poverty, slums, self-serving public institutions, violence, epidemics of drugs and diseases, misappropriation of land, and despoiling of the environment—grow upon a healthy body of everyday behavior and aspirations. The cure for these social ills rests upon a public willingness to give the highest priority to the commonplace values of everyday life. Urban crises of the past have been answered by reforms which appealed to the cultural uniformities of the city, and such partial successes show the soundness of such a strategy. But because our political, economic, and social institutions have remained in the hands of the white and the well-to-do, who have chosen to interpret our common culture primarily in terms of rewards for those who succeed and punishments and neglect for those who fall behind, the major causes of our urban maladies have gone unattended. By stressing the value of private competition in the cluster of American aspirations, the well-to-do have legitimized their behavior. At the same time, the losers, in order to understand what was happening to them, have depended upon this same orientation to validate their personal experience. This overwhelming priority for family striving has continually submerged the other behaviors and attitudes of our culture, and therefore the other needs and aspirations have been unable to sustain any enduring efforts to allocate the political, economic, social, and physical resources of the city for the benefit of all its citizens.

Since the existence of a common urban culture is of the utmost importance to any hopes for democratic planning, the history of the process whereby a diversity of migrants became a common people is well worth understanding. This chapter will summarize that history and review some of the recent social science literature on the uniformities and variations now extant in the neighborhoods of the metropolis. The ensuing chapters will show how this culture has fared in respect to two of its universal needs and aspirations: housing and health care. As this story shows, it is the overwhelming of our common culture by the structures of unequal power and wealth which constitutes our chronic urban disease.

The interactions among the economy, the internal structure of cities, and the patterns of migration have produced a common culture whose variations can be interpreted in terms of class and religious identification. Current social science suggests that about 90 percent of the American population can be classified by noting people's class and socioreligious attitudes. Most of our city dwellers have a common American culture but differ according to whether they are upper class, middle class, working class, or lower class. They also differ according to whether they are white Protestant, white Catholic, white Jewish, or black Protestant.

The origins of class attitudes are easy enough to account for. Just as the unfolding economy produced our segregated urban structure, so each day it sifts and grades its members, rewarding some more highly than others. Some men, like Marquand's top executives, inherit or earn large personal fortunes; others push their families forward into power and affluence by means of long years of education and the common striving of a young husband and wife, the sort of steps stressed in Whyte's Organization Man ; still others, like Henry's Bill Greene, can see only a limited future and while teen-agers give up the struggle and spend their lives in routine hard work and domestic comfort. Finally, there are those for whom the economy of the city is essentially closed, men like Liebow's Tally or Harrington's other Americans.[1]

Out of the repetition of thousands of such similar personal experiences come the basic class dimensions of our culture and the common

[1] . John P. Marquand, Point of No Return , Boston, 1949; William H. Whyte, Jr., The Organization Man , New York, 1956; Jules Henry, Culture Against Man , New York, 1963; Elliott Liebow, Tally's Corner , Boston, 1967; Michael Harrington, The Other America , New York, 1962.

attitudes and behavior of the upper class, the middle class, the working class, and the lower class.

Yet if one restricted oneself to interpreting the conditions and conflicts of the modern city only in terms of class, the outcome of most elections would be wrongly predicted, and strife over housing, zoning, bussing, schools, police, traffic, and taxes would be unintelligible. The reason that class is an inadequate key to the modern city is that, superimposed on the class-graded cultural variations of Americans, lie the broad bands of their racial and religious identifications: white Protestant, white Catholic, white Jewish, and black Protestant. These religious loyalties derive from our population history. We are a nation of immigrants, and these four socioreligious allegiances have matured out of the process of adaptation of immigrants to the circumstances of American urban life. Over time these loyalties absorbed the immigrant's previous ties to the village, the region, the ethnic group, the religious denomination, or the nation, so that now all but a small fraction of our citizens identify themselves to a greater or lesser degree with the four broad socioreligious orientations.

All American families share a remarkably uniform urban experience, an experience compounded of class, ethnicity, and religion. The pattern is migration, followed by the ghetto or the slum or just hard times in the city, and this is succeeded by the eventual emergence into a stable income position, be it good or bad (and for many it is good), then the church and the suburb. Behind the migrations lay tribes, villages, or family farms, depending on whether the family memory went back to Africa, Europe, or the rural United States. But as each family lives through its experiences in this country, each one passes through the acid of the city which burns off the special qualities of the past. In this corrosive environment Sicilian villagers became Italians, and Italians became neighborhood Catholics; Alabama farm boys, black and white, became slum family men, and family men became builders of Baptist or Methodist churches.

This sequence was, and still is, the sequence of the urbanization of our rural migrants. Put most crudely, one brings to the city an extremely localized culture. After some years in the city the culture becomes broader than the former village or town; it becomes ethnic. The most enduring ethnic cultural institutions in American cities have proved to be the churches, so that over the years or generations ethnic loyalties become merged into religious loyalty. Simultaneously job, income,

housing, and neighborhood teach the class structure of the city, so that in time for some a few years, for others a generation or two—a class and religious culture determines the orientation of all city dwellers. This is a simple model to cover a complex urban and population history, but it seems to order the sequences of the past hundred and fifty years in such a way as to make the contemporary city intelligible.[2]

1820-1870

The population history of the country during the first period of urbanization and industrialization had four notable characteristics. First, the native population prospered and moved westward to fill the continent. At the same time, Americans began sharply to control the size of their families so that population growth after the middle of the nineteenth century no longer depended solely on native reproduction. Second, millions of immigrants from Germany and Great Britain came to join the native population in its westward migration, and they also adopted the new style of the small family. Third, the collapse of the Irish economy expelled millions from that country and added a heavy stream of Irish to the transcontinental flow (Table 3, page 168). They too followed the predilection for family limitation. Fourth, interaction between evangelical Protestantism and Catholicism—especially of the Irish variety reformed two basic elements in American urban culture, the broad Protestant and Catholic allegiances.

At least until 1870, when the standard of living commenced its steady rise in both the United States and Europe, the story of our population and its immigrants was the story of poor farmers, poor peasants, and poor artisans accustomed to subsistence living, who in moving were seeking an opportunity for a decent living for themselves and their families. The sheer abundance of cheap farmland .enabled the

[2] . There is an extensive literature devoted to this model which I have used to build this cultural history: Ruby Jo Kennedy, "Single or Triple Melting Pot? Intermarriage Trends in New Haven 1870-1940," American Journal of Sociology , 49 (January 1944), 331-39; Will Herberg, Protestant, Catholic, Jew , New York, 1955; Gerhard Lenski, The Religious Factor: A Sociological Study of Religious Impact on Politics, Economics, and Family Life , New York, 1961; Oscar Handlin, "Historical Perspectives on the American Ethnic Group," Daedalus , 90 (Spring 1961), 220-32; Seymour Martin Lipset, The First New Nation , New York, 1963; Milton M. Gordon, Assimilation in American Life , New York, 1964; Nicholas J. Demerath, Social Class in American Protestantism , Chicago, 1965; Mark A. Fried, "The Role of Work in a Mobile Society," in Planning for a Nation of Cities , Sam Bass Warner, Jr., ed., Cambridge, 1966, pp. 81-104.

great mass of the nation's white farmers to support large families and for their children to survive. In this era, as always in our history, the rural areas supplied a disproportionate number of the nation's children; even today rural births consistently outrun those in town or city. Moreover, until the twentieth century the death rate among children in American cities was always higher than in the countryside.

Up to 1840 almost all population growth stemmed from natural increase, white and Negro, and although the birth rate fell steadily during the nineteenth century, until 1860 it still continued to exceed European rates. From then on, American birth rates declined in the same general ratios as those of England, France, and Sweden. Scholars do not yet understand the cause of this decline; but it is a long-term historical trend participated in both by natives and immigrants, with only a few very short exceptions and slight reversals. For the moment, all that can be said is that Americans and Europeans limit their families as they become urban industrial peoples.[3]

The native population established the directions for the streams of continental migration which the immigrants followed. Prior to 1870 Americans moved westward in roughly parallel bands: migrants from New England and New York filled the upper Midwest; families from the Southeast settled the lands from Alabama to Texas; and people from Virginia and Pennsylvania settled in Kentucky, Tennessee, and Missouri, and in southern Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. With the coming of the railroad and the rapid development of the Midwest, settlers from the entire North and Midwest overran the plains, mountain, and Pacific regions.

Slavery was an effective barrier against mass European immigration into the South, but millions of Germans, English, Scots, Welsh, and Irish joined the westward movement in the fifty years after 1820. Farm counties in the Midwest were as rich an ethnic patchwork in those years as the blocks of Manhattan.

Historians of the era have fully documented the special ethnic contributions brought by these immigrants to the first stages of our urbanization and industrialization. In the mill town of Lowell, Massachusetts, there was an "English Row" of houses belonging to calico printers from

[3] . Conrad and Irene B. Taeuber, The Changing Population of the United States , New York, 1958, p. 294; Susan E. Bloomberg, Mary Frank Fox, Robert M. Warner, and Sam Bass Warner, Jr., "A Census Probe into Nineteenth Century Family History: Southern Michigan 1850, 1880," Journal of Social History , 4 (Fall 1971), 26-45.

Lancashire; English and Scottish workers supplied the skilled labor in the cotton and woolen mills of New England and New York; the woolen weavers and knitters of Philadelphia and Lowell, as well as those of Thompsonville, Connecticut, were Scottish. In the 1820s, English, Scottish, and Welsh miners opened up the anthracite mines of eastern Pennsylvania, Maryland, Ohio, Illinois, and what is now West Virginia. Cornishmen, seeking lead, were the first foreigners to settle in Wisconsin; they also dominated copper mining in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and they cut the first railroad tunnels through the Berkshire Hills. The early history of American labor inherited many of its distinguishing features from the British tradition. The great "Ten-Hour" strikes of the big cities, when skilled artisans turned out in vast numbers to demand shorter hours and higher pay, the first fraternal organizations like the Masons or the Odd Fellows, and many of the workers' insurance and benefit funds were in most places initiated by English and Scottish immigrants.

No city or town north of the Ohio River was without a German quarter, and many of the small towns were composed almost entirely of Germans. In the big cities German peasants suffered from poverty and slum housing as severely as did the thousands of Irish peasants and were as cruelly exploited in the cheapest trades. Like the English, however, the skilled among them maintained their tradition of workingmen's associations which flourished in all manner of clubs, benefit associations, and labor organizations.

The new people also brought with them the conflicts of the British Isles. Cornish and Irish mobs—the "pasties" versus the "codfish"—fought pitched battles in the copper country of upper Michigan; the rooms of the New England textile mills were segregated to the disadvantage of the Irish; English and Irish Protestants brawled and rioted in every city; and the murders by the Molly Maguires were an echo of less drastic Irish attacks on their British colliery foremen.[4]

Yet many of the qualities peculiar to the various immigrant cultures were soon lost. Those which could easily be absorbed, like labor unions and lager beer, disappeared into the general cultural scene, and individual manifestations were ground off in the cultural clash between Protestant and Catholic. The 1820-1870 migrations of German and

[4] . Rowland T. Berthoff, British Immigrants in Industrial America 1790-1950 , Cambridge, 1953, pp. 30-87, 185-92; Robert Ernst, Immigrant Life in New York City 1825-1863 , New York, 1949, pp. 61-98.

Irish Catholics met a special kind of Protestantism when they landed—not an established state religion but a collection of thousands of small congregations. But for all its fragmentation, Protestantism flourished during these years and developed into a general Protestant-American consciousness.

A blend of the colonial institutional inheritance with later religious enthusiasms gave the Protestantism of the years between 1820 and 1870 its particular character. Late eighteenth-century colonial Americans had not been churchgoers. Theirs was probably the most secular of all our cultural periods, and scholars estimate that only 10 percent of the population at most belonged to any church at all. Simultaneously the Revolution gave rise to the apprehension that established churches were agents of monarchical tyranny and laid down a tradition that our nation would be one without state-supported churches. All Protestant denominations were in effect compelled to become voluntary, competitive organizations. Except perhaps in the case of the Quakers and some pietists, Protestantism was oriented toward bringing in the unchurched, and most congregations for the sake of their own survival had to adopt not an exclusive but a recruiting mission.[5]

Our colonial history was marked by continual strife along denominational lines—among Anglicans, Quakers, Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Baptists, Methodists, and pietists of various kinds. Some of the confrontations were of course plainly rooted in the home countries, as in the cases of German pietists or Scotch-Irish Presbyterians, but many were not. When Massachusetts Congregationalists persecuted Quakers or Baptists, or when Connecticut Congregationalists expressed their disapproval of Methodists, they were discriminating against their own kind.

The evangelical drives for membership dampened interdenominational conflict and eroded doctrinal lines. Most late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century American Protestants believed that the individual had to discover God, not vice versa, and that there were rewards and punishments in this world and the next for good Christian behavior. Accordingly waves of evangelism, with ministers welcoming the unchurched into Protestant fellowship, swept the country from 1795 through the next half century or more.

A millennial hope that the spread of Christianity and of liberal

[5] . Sidney E. Mead, The Lively Experiment: The Shaping of Christianity in America , New York, 1963, pp. 16-37, 103-33.

human institutions would bring the Kingdom of God to the United States suffused the era. The means, of course, were individual, "an elevated state of personal holiness."[6] Churchgoing grew more popular. Simultaneously Protestantism became more and more unified both in doctrine and practice, and no deterrent stood in the way of intermarriage between members of different denominations. When conflict arose with Catholic immigrants, a generalized Protestant sentiment defended the voluntarism and individualism of their way of life and warded off Catholic incursions into Protestant control of political organizations and public institutions for education and welfare.

As always in America, the blacks had a separate history. At the time of the Revolution there were no Negro congregations in Northern cities. Blacks attended white Protestant churches, although sometimes, as in Philadelphia, they were segregated to a balcony. In the early nineteenth century the growing emancipation and democratic sentiment in the small black colonies of the Northern cities engendered a move toward self-determination for Negroes in religious matters, so that by the 1840s every city had its black churches and fraternal organizations. The full flowering of this black urban culture nevertheless awaited the substantial migration of blacks to Northern cities, which began in the 1890s.[7]

The massive migration of Germans and Irish from 1830 to 1870 changed the religious composition of the nation. Since the seventeenth century America had been a Protestant country, whether or not devoutly or secularly so; now it became a Protestant-Catholic nation. By 1870 Catholics constituted the largest single religious group, about 40 percent of the churchgoers, and such has been the balance of immigration ever since.[8] A drastic leap in numbers, however, did not immediately imply a unified American Catholicism. Instead, Catholicism during this era was able only to discover and lay down the institutional framework on which later generations would build a Catholic culture for all classes. Until

[6] . Quote from Reverend Edward Beecher in Timothy L. Smith, Revivalism and Social Reform in Mid-Nineteenth Century America , New York, 1957, p. 225.

[7] . Leon F. Litwack, North of Slavery: The Negro in the Free States 1790-1860 , Chicago, 1961, pp. 187-213.

[8] . In the absence of reliable data there is an unavoidable vagueness in estimates of past religious involvement. Lipset, who focuses on attendance, suggests a constant level of participation, while Edwin S. Gaustad, who works from church membership, proposes a rising religiosity. I have chosen the latter method because it is comformable with the accounts of evangelical revivals during the first half of the nineteenth century. Lipset, First New Nation , pp. 160-71; Gaustad, Historical Atlas of Religion in America , New York, 1962, pp. 110-11.

then, the poverty and fragmentation of the Church and its immigrant membership outweighed every extraneous consideration. Yet in facing poverty, fragmentation, and the contemporary Protestant attack, the foundation of a broad cultural unity was formed.

A nineteenth-century American Catholic, whether immigrant or native-born, inevitably bore an inherited reputation for having advanced the traditions of "popery," which had been the bogy of Great Britain for two hundred and fifty years and had made Catholics the object of deep-seated national prejudice there. Through English colonists and the colonial wars against the French this prejudice was transferred to America, and Catholics of whatever origin were stamped as a negative reference group in the early Republic. Events overseas made matters worse. The campaign in England to remove the last civil penalties from Catholics spawned a deluge of anti-Catholic literature that poured across the Atlantic until the passage of the Catholic Emancipation Act in 1829. At the same time, Protestant ministers and organizations were single-mindedly seizing on anti-Catholicism to inspire popular enthusiasm for affiliating with a Protestant church. The American Bible Society not only published anti-Catholic tracts but even launched a campaign to spread the King James Bible among Catholics. The campaign naturally aroused an angry response among the American bishops. Furthermore the stubborn refusal of poor immigrants to accept the free Bibles gave rise to a widespread belief that Catholics were opposed to the Bible—a conviction that was to play a prominent part in the public-school and nativist controversies of the forties and fifties. Finally, well-known Protestant ministers began to preach anti-Catholic sermons as part of their proselytizing efforts. The Reverend Lyman Beecher of Boston delivered three Sunday sermons in as many churches on August 10, 1834, speaking out violently against Catholicism and its regular clergy and further inflaming an already explosive situation in that city. He and his fellow ministers may be said to have contributed directly to the first burning of a convent in the United States, which took place on the following day. All this fervor, anger, and prejudice preceded (or dated from the very start of) the great wave of German and Irish Catholic immigration. When that tide appeared, the nation's cities, large and small, entered upon three decades of anti-Catholic rioting marked by the burning of churches, orphanages, and convents.[9]

[9] . Ray A. Billington, The Protestant Crusade 1800-1860 , New York, 1938, pp. 32-76.

The frequency and virulence of Protestant attacks did not automatically unite the largely impoverished mass of native American, French, German, and Irish Catholics. In 1820 the church was a weak and scattered organization made up of parishes from the old French empire at New Orleans, St. Louis, and Detroit, from the old colonial parishes in Maryland and their more recent offshoots in Kentucky, and of churches in most of the Eastern cities. Because there was but one major facility for training diocesan priests here, St. Mary's Seminary in Baltimore, priests had to be recruited from France, Germany, Italy, England, and Ireland, and they brought with them the diverse national styles endemic to European Catholicism.[10] In addition, no strong hand existed to enforce unity. During the long colonial years of intolerance and penalties against Catholics and of official neglect by the English bishop who had formal charge, priests here evolved an independent collegial style for the management of their common affairs. Perhaps fortunately for Catholicism in America, in view of the variety of backgrounds of the new waves of immigrants, the early nineteenth-century Church depended upon the initiative of scattered bishops who coped with their growing dioceses as best they could. Differences among them had to be reconciled by occasional provincial meetings, most frequently held in Baltimore, where the bishops gathered to legislate for the American Church. In its decentralization and widespread use of democratic and federal forms both within dioceses and among them, the Church of these years reflected the general political thrust of its era.[11]

By 1870 the Catholic Church had four and a half million members. Its parishes were scattered across the land from city slums to Midwestern farm counties, along the banks of every railroad and canal from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Such massive growth forced the Catholic Church into a position not unlike that of its Protestant opposition. The sheer necessity of building churches at a rate rapid enough to bring the Mass within reach of the incoming tides of newcomers necessarily delivered much of the power of the organization into the hands of the parish. Popular church-building priests and successful fund-raising congregations became the models of the day. Although Catholic immigrants

[10] . John Tracy Ellis, "A Short History of Seminary Education: Trent to Today," in James M. Lee and Louis J. Putz, eds., Seminary Education in a Time of Change , Notre Dame, 1965, pp. 46-57.

[11] . James Hennesey, "Papacy and Episcopacy in Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century America," Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia , 77 (September 1966), 175-84.

varied a great deal in their use of the Church, some depending upon it solely for its sacraments and others, especially Germans, bringing with them a custom of a village church and related clubs and societies, one can see in this emphasis on fund raising and on the building of churches and parochial schools the beginnings of the transformation of many a European church into the typical American Catholic parish of bingo, basketball, and building funds.

The ethnically fragmented hierarchy and parishes and the pressure for church building were manifested in a particular movement of local-ism—trusteeism—during these years. The trustee movement surfaced in open conflict immediately after the Revolution when local congregations asserted their right to appoint priests and control parish budgets in place of the bishop. In New York, Philadelphia, New Orleans, Norfolk, and Buffalo certain parishes resisted all attempts at discipline for as long as forty years. The difficulties had many dimensions, but the ethnic one proved to be the most obdurate. English priests had been the first to staff the American Church, and trustee clashes took the form of battles between American parishioners and the customs of French priests who fled here from the French Revolution, or between newly formed Irish congregations and native and French styles. Irish-German confrontations fired by English-language conflicts arose in the North and Midwest.[12]

To cope with these conflicts—and they remained bitterly divisive throughout the nineteenth century—the Church was compelled to adopt the rule that special churches for single nationalities might be established within the boundaries of the parishes established for each diocese. Moreover, the bishops endeavored to maintain harmony by calling regular meetings of all the parishes under their supervision. This episcopal compromise, later repeated when Catholics from Southern and Eastern Europe arrived, made it possible for the Church to maintain a troubled unity during the great migrations of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[13] So successful were these devices in enabling the Church to stay in contact with newly arrived immigrant groups that

[12] . John Tracy Ellis, ed., Documents of American Catholic History , Milwaukee, 1956, pp. 155-58; Thomas T. McAvoy, A History of the Catholic Church in the United States , Notre Dame, 1969, pp. 93-122; John Tracy Ellis, American Catholicism , rev. ed., Chicago, 1969, pp. 45-50.

[13] . Theodore Maynard, The Story of American Catholicism , New York, 1941, I, pp. 219-28; John Tracy Ellis, The Life of James Cardinal Gibbons, Archbishop of Baltimore, 1834-1921 , Milwaukee, 1952, I, pp. 331-88.

when the twentieth-century Church began to speak for all the urban poor in political and philanthropic affairs, the general public found this representation acceptable.

Perhaps even more important for future Catholic culture than the halfway house of the ethnic Church was the establishment of parochial education. The beginning of the parochial system is customarily dated from the opening of a school for poor children in 1810 by Sister Elizabeth Seton at St. Joseph's Parish in Emmitsburg, Maryland. She employed the Sisters of Charity, of whom she was the American founder, to staff the school, and she operated it with free materials and without tuition for the children of the area. The basic formula of an elementary school attached to every church was seized upon by the most ambitious bishops as the best chance for the survival of Catholicism in Protestant America. In 1884 the Council of Baltimore adopted it as the official task of all dioceses. Thus, unlike in Europe, where universal education was yet to be established as a national norm, and where state funds and long-established endowments supported both churches and schools, American Catholic communities faced a double burden of creating a network of schools and churches sufficient to serve the waves of immigrants flooding in from abroad. The sheer poverty of some Catholic communities, like that of Boston, doomed the effort to failure in these first decades. Elsewhere, especially in German-settled cities where the desire for foreign-language teaching lent an additional impetus for local support, and in dioceses of aggressive bishops who successfully solicited funds and teaching orders from Europe, a rough approximation of the goal was attained before the Civil War.[14] Despite the universal emphasis of the parochial-school drive for a free education for every Catholic child, such a massive and relentless fund-raising effort imposed its class mark on Catholic education because it firmly anchored the parochial system to the parents of children of the working class and middle class, the very members of each urban parish who were making their way most successfully.

The building of the parochial system, begun on a large scale to meet the needs of the immigrants' children in the 1840s, had two consequences for American urban culture. First, it began the secularization of the public schools, dominated until that time by Protestants; second, it helped to build a characteristically American style of Catholic culture.

[14] . Harold A. Buetow, Of Singular Benefit, The Story of Catholic Education in the United States , New York, 1970, pp. 60-63, 108-54.

During the forties, Bishop John Hughes of New York and Bishop Francis Kenrick of Philadelphia pressed for the abolition of Protestant teaching in the public schools and for municipal or state aid to parochial schools. An explosion of antiforeign, anti-Catholic prejudice, resentment, and rioting greeted these demands. In every state where Catholics sought funds in the mid-nineteenth century they were refused. Not only did this outcry tend to draw German, Irish, and American Catholics together, but the gigantic effort required to build and to maintain thousands of schools committed each parish to an enduring social task: the education of children. The goal of literacy, both Catholic and secular, for any child who presented himself at the school door meant that the Catholic Church was as securely tied to the task of Americanization through education as were the contemporary public schools. Moreover, because the building and financing of its schools rested with the families of the parish, the values of the Church itself became tied to the hopes and values of child rearing which its neighborhood supporters possessed.[15]

1870-1920

The migrations of native Americans during the second era of urbanization and industrialization reflected some specific changes in the economy. The last years of the nineteenth century and the first two decades of the twentieth have been characterized as the "golden age of American agriculture."[16] It was a time when skillful farmers, using new techniques taught by the agricultural colleges and extension stations, prospered as world prices rose for American staples. The contemporaneous completion of the railway network opened up the high plains, Florida, the Southwest, and the Pacific coast so that every variation in soil and climate was utilized by farmers universally bound to national and international marketing systems.

The completion of the westward movement did not however halt the migratory habits of our restless people. After 1870 systematic information becomes available for the state-by-state migrations of the native-born. There was no settling down. In any given census since 1870,

[15] . Vincent P. Lannie, Public Money and Parochial Education , Cleveland, 1968, pp. 247-58.

[16] . Allan G. Bogue, From Prairie to Corn Belt , Chicago, 1963, pp. 280-82.

one-quarter of the population was living outside the state of its birth.[17] Moreover, this documented migration followed the time-honored pattern of the common people: young men, women, and families moved because they were seeking the places where economic opportunity seemed the best. Although in 1920 there were more farms and farmers in the United States than ever before or since, modernization of the economy had already begun to drive many Americans off the land.[18] The young people especially were aware of a choice between farm and city; many of them were sick of farming and began to pour into the cities and towns of the Midwestern manufacturing belt. The Lynds' first Middletown book records the transformation which such shifts from a rural to an industrial society entailed for a small Midwestern city. But the country people also poured into the great cities of the era, helping to build such metropolises as Pittsburgh, Chicago, Cleveland, and Detroit.[19]

During these same years, international immigration reached its flood but did not retrace the patterns of native population flow to the degree that it had in previous years. Only Scandinavians, Bohemians, and some Germans continued to move out onto the farms to swell the westward migration of the natives. Most Europeans were concentrated in the cities and towns of the Northeastern and Midwestern manufacturing belts, thereby settling themselves in the forefront of the urbanization of the era.[20]

Historians refer ,to the migrations of 1870-1920 as the years of the "new immigration," that is, the coming of the Russians, Poles, and Italians as opposed to the "old immigration" of Germans, Irish, and British (Table 3). The shifts in origins and ratios of European migrants reflect the interaction between the modernization of Europe and the industrialization of the United States. For Europe as a whole there were periods of heavy excesses of births over deaths, and these were of course the times of large population gains. When the children represented by these gains reached adulthood, mass migrations took place from rural

[17] . U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1957 , Washington, 1960, p. 41.

[18] . The 1920 returns reported 3,366,510 farmowners. Historical Statistics, p. 278.

[19] . Robert M. Fogelson, The Fragmented Metropolis, Los Angeles, 1850-1930 , Cambridge, 1967, p. 69; Robert S. and Helen M. Lynd, Middletown , New York, 1929.

[20] . David Ward, Cities and Immigrants, A Geography of Change in Nineteenth-Century America , New York, 1971, pp. 65-81; Brinley Thomas, Migration and Economic Growth , Cambridge, England, 1954, pp. 133-34.

TABLE 3 . | |||||||||||

Total | Great Britain | Ireland* | Germany | Other Central Europe** | Russia- | Italy | Asia | Canada | Mexico | Balance of World | |

1821-30 | 143 | 25 | 51 | 7 | n.a. | — | — | — | 2 | 5 | 53 |

1831-40 | 545 | 76 | 207 | 152 | n.a. | — | 2 | — | 14 | 7 | 87 |

1841-50 | 1,713 | 343 | 781 | 434 | n.a. | 1 | 2 | — | 42 | 3 | 107 |

1851-60 | 2,598 | 424 | 914 | 952 | n.a. | — | 10 | 41 | 59 | 3 | 195 |

1861-70 | 2,215 | 607 | 436 | 787 | 8 | 2 | 12 | 65 | 154 | 2 | 142 |

Subtotal | |||||||||||

1821-1870 | 7,214 | 1,475 | 2,389 | 2,332 | 8 | 3 | 26 | 106 | 271 | 20 | 584 |

1871-80 | 2,812 | 548 | 437 | 718 | 73 | 39 | 56 | 124 | 384 | 5 | 428 |

1881-90 | 5,247 | 808 | 656 | 1,453 | 354 | 213 | 307 | 68 | 393 | n.a. | 995 |

1891-1900 | 3,688 | 272 | 389 | 505 | 593 | 505 | 652 | 71 | 3 | n.a. | 698 |

1901-10 | 8,795 | 526 | 339 | 341 | 2,145 | 1,597 | 2,046 | 244 | 179 | 50 | 1,328 |

1911-20 | 5,736 | 341 | 146 | 144 | 902 | 922 | 1,110 | 193 | 742 | 219 | 1,017 |

Subtotal | |||||||||||

1871-1920 | 26,278 | 2,495 | 1,967 | 3,161 | 4,067 | 3,276 | 4,171 | 700 | 1,701 | 274 | 4,466 |

1921-30 | 4,107 | 330 | 221 | 412 | 215 | 89 | 455 | 97 | 925 | 459 | 904 |

1931-40 | 528 | 29 | 13 | 114 | 32 | 7 | 68 | 15 | 109 | 22 | 119 |

1941-50 | 1,035 | 131 | 27 | 227 | 38 | 4 | 58 | 32 | 172 | 61 | 285 |

1951-60 | 2,516 | 209 | 64 | 346 | 182 | 47 | 188 | 150 | 275 | 319 | 736 |

1961-70 | 3,322 | 230 | 43 | 200 | 99 | 16 | 207 | 431 | 287 | 443 | 1,366 |

Subtotal | |||||||||||

1921-1970 | 11,508 | 929 | 368 | 1,299 | 566 | 163 | 976 | 725 | 1,768 | 1,304 | 3,410 |

* Includes both Northern and South Ireland | |||||||||||

** Austria since 1861, except 1938-45, Hungary since 1861, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia since 1920. There is no long unbroken time series available for Poland. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States, Washington, 1960, pp. 56-59; U.S. Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service, Report of the Commissioner: 1970, Washington, 1971, pp. 63-64. | |||||||||||

areas into European cities and beyond to America. The impact of the baby booms of 1825 and 1840-45 in Western Europe had propelled the tides of German, Irish, and British migrants. In later years as railroads and urbanization stimulated the Eastern and Southern European economies, similar population booms swelled rural populations there. The birth surge of 1860-65 appeared in the American immigration peak of 1880-84; the surge of 1885-90 in the peak of 1902-15.[21]

The migrants came to this country in tremendous numbers only when jobs were plentiful here; if hard times prevailed they settled in European cities instead. Such alternative destinations for European rural migrants stemmed from the fact that the nineteenth-century cycles of building activity and capital investment were not the same for Europe and America. Until World War I the United States was a substantial importer of capital from Europe, and accordingly it had to compete with European opportunities for investment in industrial, ventures and urban real estate. Capital sought first one continent and then the other depending upon the expectations for most substantial profits. These capital flows alternately encouraged and impeded employment in the United States. The flow of capital created boom years from 1878 to 1892 and from 1897 to 1913 and opened up many new jobs, and hence there were surges in immigration. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, as cheap steamship passage made the crossing of the ocean easy and safe, skilled workmen often moved between England and the United States, following the crests in wages and employment in their particular crafts. The statistics of net migration, which show departures as well as arrivals from abroad, confirm the employment-opportunity-migration sequence.[22]

There were two immediate results of this pulsating flow of peoples from Europe. The continued flood of unskilled workers directly influenced the development of mechanization in American industry, while the interaction between the origins of immigrants and the increasing urbanization of the United States determined which groups were to advance with certain elements of the economy. With immigration bringing in tides of unskilled labor to the nation, industry before the Great Depression had always to adjust to a plentiful supply of cheap unskilled labor and to a concurrent shortage of skilled workmen. The result was

[21] . Thomas, Migration and Economic Growth , pp. 155-58.

[22] . Taeuber and Taeuber, Changing Population of the United States , pp. 67-70, 202-13.

to give our technology a particular cast: the most complicated processes were mechanized first, in contrast to European practice, in order to conserve highly skilled and paid craft workers, and were mechanized in such a way that they could be carried out by men with very little training. Gradually an industrial style of high mechanization developed. It did not always present the cheapest solution, as twentieth-century competition with German manufacture made plain, for Germany used highly skilled techniques coupled with less mechanization, but it became an enduring part of American industrial culture.[23]

The second consequence of the shifting origins of European migration was that it aroused considerable alarm among both native Americans and children of the older immigration. To be sure, those native-born who moved to the cities, factories, and offices of the nation had a strong competitive advantage over most foreigners. They often possessed more formal education, some savings, and connections with well-placed relatives. Above all, they were members of the dominant culture. Studies of social mobility show that the native-born and their children moved more easily into white-collar jobs than did the immigrants or their children. Yet during the 1870-1920 years native Americans were disproportionately concentrated in the farms and small towns of the United States, and their apprehensions that they were being left behind contained some measure of truth.

For example, national statistics show that the children of English and Irish immigrants achieved high-status positions more rapidly than the native population did simply because their parents had settled in greater concentrations in the cities; and since in the half century after 1870 these were the locations of widest opportunity, the immigrant child had a better chance for education and for an eventual high-status position. In 1900, 5.7 percent of all white Americans were illiterate as opposed to only 1.6 percent of the children of immigrants. In that census year the ratios of whites in professional and clerical positions and in government employment summarize the differential effects of migration, urbanization, and social mobility: 14 percent of all Americans appeared in these categories but 22.6 percent of the children of both British and Irish immigrants. Because of their traditional rural position

[23] . Sigfried Giedion, Mechanization Takes Command , New York, 1948, p. 38; John A. Kouwenhoven, Made in America: The Arts in Modern Civilization , New York, 1948, pp. 13-42.

in the economy, native Americans as a whole were indeed being left behind.[24]

Conditions prevailing in the new mill towns and metropolises of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries also conspired to shake the confidence of both native and "old immigrant" stock. The men there had acquired the urban industrial skills of their day and counted on the continuation of the nineteenth-century world, where the continual arrival of fresh unskilled immigrants signaled not only expansion of the job market but also promotion and advancement for earlier comers. Under this mode of growth in the economy, natives and old immigrant groups had become the skilled hands, the foremen, the bosses of the new incursions of rural migrants. The repetition of this sequence of events had meant that for at least the previous century immigration and social mobility had had no grounds for conflict.

In the 1890s the scale of the city and of industry reached swollen proportions, and the scope and possibility for the social and economic mobility of the ordinary citizen seemed to narrow. Although studies by historians seem to show that the chances for individual advancement did not in fact decline during the years after 1890, nevertheless a feeling was prevalent that a man's chances to get ahead had dwindled with the coming of the giant metropolis and the factory. For the first time, the waves of European immigrants appeared as a threat: perhaps to the workers of the time, certainly to their children. As unions became fearful for the jobs of their members, the men lost confidence in the future for themselves and their children.[25]

Concomitantly an ugly rise in ethnic stereotyping swept the nation. Racial prejudice, anti-Semitism, anti-immigration sentiment, and the inflated patriotism of World War I with its phobia against Communism combined to pass in 1921 an immigration law that set limited quotas based on the ethnic mixture of the population as it was found to exist in 1910. So it was that fear of the industrial structure and of the metropolis that housed it, augmented by jealousy between rural and urban dwellers, ended the century-old pattern of migration, industrialization, and urban-

[24] . Taeuber and Taeuber, Changing Population of the United States , p. 187; Thomas, Migration and Economic Growth , pp. 141-54; E. P. Hutchinson, Immigrants and Their Children 1850-1950 , New York, 1956, pp. 203-16.

[25] . John Higham, Strangers in the Land , New Brunswick, 1955, pp. 158-233, 300-330; Stephan Thernstrom and Richard Sennett, eds., Nineteenth Century Cities: Essays in the New Urban History , New Haven, 1969, pp. 125-64.

ization. The atmosphere since the twenties has been a miasma of anti-foreign sentiment. The paradoxical result of the 1921 law and its subsequent revisions was to close immigration from peasant countries and to encourage the entrance of skilled workers and professional men from the more advanced countries, thereby exacerbating competition for the most prized jobs. Our nation with its high levels of skill and education thus continued to draw the trained sectors of population away from those nations that had the most crying need for modern skills.[26]

During the last years of the nineteenth century, the black population of the United States began to move from its historic place in the rural Southeast. The special qualities of Negro migration in America have been twofold: it has been small compared to both native-white and European migrations, and it is a migration that has taken place under severe handicaps, because for many years it proved difficult for blacks to escape from their home territory.

Like earlier migrants, the blacks followed existing transportation routes, pursuing the cheapest paths. Negroes from Maryland to Florida came by coastal steamer and railroad to the cities of the Northeast. Negroes west of the Alleghenies moved up the Mississippi by rail on the Illinois Central, Gulf Mobile and Ohio, and the Wabash to St. Louis, Chicago, Cleveland, and Detroit. The pioneering settlers were young people who ventured north to seek a place in the small ghettos that had existed in every city since before the Civil War. The availability of jobs in Washington, D.C., fostered a large colony there of blacks from Virginia and the upper South, while industrial and service jobs in Philadelphia and New York attracted blacks along the Atlantic. As in other migrations the pioneers sent back letters of encouragement, sometimes money and tickets, and the channels of migration opened and began to flow, pulsating with the rhythms of urbanization and economic growth. During both World Wars this normal migration was spurred by the active labor-recruiting policies of the steel mills and other large firms in need of quantities of cheap labor. Indeed, the precedent for the recruitment of black Southern labor lay in the nineteenth-century practices of those companies who had imported gangs of laborers from Italy and Eastern Europe.[27]

[26] . Taeuber and Taeuber, Changing Population of the United States , p. 70.

[27] . Carter G. Woodson, A Century of Negro Migration , New York, 1918, pp. 147-92; Gilbert Osofsky, Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto , New York, 1963, pp. 17-34; Constance McLaughlin Green, Secret City: A History of Race Relations in the Nation's Capital , Princeton, 1967, pp. 119-93. The greater difficulty of blacks in moving out of their home states in the South can be shown by comparing white and nonwhite migration from Alabama and Virginia for the years 1870 and 1910: Everett S. Lee, Ann R. Miller, et al., Population Redistribution and Economic Growth, United States 1870-1950 , I, Philadelphia, 1957, pp. 249, 293, 299, 343.

Although the total volume of black migration remained small until World War II, it was enough in the early years to create in New York, Chicago, and St. Louis black ghettos that would nurture the beginnings of a modern urban American Negro culture. The Harlem Renaissance in New York began with the first waves of late nineteenth-century northward migration.[28] The timing of the start of black migration, however, proved to be disastrous. Negroes began arriving in large numbers in Northern cities exactly at the time when the great swells of fear and prejudice had begun to break over America, indeed over all the European world as well. The bitter race riots of East St. Louis in 1917 and of Chicago in 1919 testify to the anger and brutality of the climate into which the native blacks were moving in their search for opportunities in the cities of the North.[29]

The cultural effects of these new sources and differential patterns of migration immediately manifested themselves. The coming of the Jews from Eastern Europe and of the black Protestants from the South completed the roster of elements that compose our modern urban culture: white Protestant, white Catholic, white Jewish, and black Protestant. Yet since each of these socioreligious clusters consisted largely of recent rural migrants, American and European, the cultural life of each group evolved around its adjustments to new urban conditions. Each group accordingly developed pronounced old-value and new-value wings.

For the white Protestants the important cultural event of the years from 1870 to 1900 was the formation of a liberal, urban middle-class movement—the social gospel—extending laterally across all denominations. The movement reflected a self-conscious attempt on the part of Protestant ministers and laymen to comprehend and make some adjustment to the realities of their day. It drew upon the millennial enthusiasm of the earlier evangelical era but transformed it into a secular optimism based on the efficacy of social reform. It drew also upon the past emphasis on individual religious responsibility but transformed it into a

[28] . James Weldon Johnson, Black Manhattan , New York, 1930, pp. 58-125.

[29] . Elliott M. Rudwick, Race Riot at East St. Louis , Carbondale, 1964; Carl Sandburg, The Chicago Race Riots July 1919 , New York, 1919; William M. Tuttle, Jr., Race Riot, Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919 , New York, 1970.

call for an active citizenship informed by Christian ethics. The modern American Christian, according to the social gospel, was to address himself to the affairs of the world, to work as an individual and to join others in his congregation in combating such evils as child labor, exploitation of women, Negroes, and workingmen, and the social pathology of slum housing, alcoholism, and unregulated immigration.[30]

Institutionally the movement became apparent in interdenominational organizations like the Federal (later National) Council of Churches of Christ in America (1908), in the founding of settlement houses and the development of social work as a profession, in church-sponsored investigations of major strikes, and in a vast amount of debating and pamphleteering.[31] Conceptually the social gospel enlarged the old reformist wing of American Protestantism and brought this branch of the culture up to date by leading it into sympathetic contact with the realities of Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish working-class and lower-class life. Of course the old axes of conflict still existed within Protestantism. A strong draft of nativism blew through many of the Americanization programs of progressive settlements, churches, and public schools of the day. The temperance and antiprostitution campaigns, so important in these years, were at once real issues of social liberation and continuations of early nineteenth-century Protestant-Catholic warfare over alcohol, dancing, and Sabbath observance.[32] Yet for all this persistence of old habits of thought the social-gospel wing of Protestantism initiated the very important task of establishing a modern liberal middle-class sentiment that could build bridges to the three other contemporary urbanizing cultures.

The great majority of both rural and urban Protestants were not in any case followers of the social gospel. In these years urban Protestantism lost much of its older working-class base and became very much a middle-class suburban phenomenon. Moreover, the new rich of the city dominated many congregations with their conservative blend of self-righteous capitalism and old-fashioned insistence that poverty was a manifestation of unworthiness and sin.

[30] . Henry F. May, Protestant Churches and Industrial America , New York, 1949, pp. 163-203.

[31] . C. Howard Hopkins, The Rise of the Social Gospel in American Protestantism 1865-1915 , New Haven, 1940, pp. 257-327.

[32] . Samuel P. Hays, "History as Human Behavior," Iowa Journal of. History , 58 (July 1960), 193-206; "The Social Analysis of American Political History, 1880-1920," Political Science Quarterly , 80 (September 1965), 373-94.

For Catholicism the years from 1870 to 1920 were also ones of liberalization. In Europe the liberal-national revolutions and the rise of Catholic unionism and Christian socialism drove the hierarchy into a degree of accommodation with the modern world. The deep suspicion of and hostility to humanitarian reform that had marked many Papal and American Catholic attitudes in the earlier era now gave way to a sense that the Church ought to interest itself in the problems posed by industrialization and the urban masses. Pope Leo XIII's 1891 encyclical Rerum novarum on the relations of capital and labor and the work of James Cardinal Gibbons on behalf of the Knights of Labor marked the new trend.[33]

As Irish and German Catholics rose in large numbers from immigrant poverty to positions of success and affluence, the Catholic Church became an all-class, fully organized institution in the United States. These were the years of cathedral building in every major urban diocese, the years of the widespread establishment of the parish elementary-school system and, following the trends in public education, the opening of parochial high schools. The Church began to train its own priests, and although a continuing shortage required European recruits, the Catholic Church in America became a highly integrated organization dominated by native-born descendants of Irishmen and Germans.

Much of the liberalization of Catholicism derived from the personal experience of its membership. As millions of Catholics moved out from the poverty of the central city to the new working-class settlements and middle-class suburbs, they settled in mixed Protestant-Catholic communities. The needs of the parish for church and school building and the associational style of middle-class Americans caused Catholic clubs and societies to multiply as they did at neighboring Protestant churches. The charitable work of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul and the fraternal organization of the Knights of Columbus proved immensely popular.

Catholicism did not, on the other hand, become absorbed in the social gospel in the same way that contemporary Protestantism had done. The social gospel was after all a movement of middle-class people, often with small-town backgrounds, who were trying to come to grips with the strangeness of the industrial metropolis. Catholic liberalism in these years most commonly took the form of speeches made by Irish and German politicians and priests in behalf of the working classes and

[33] . Ellis, American Catholicism , pp. 101-104; Ellis, Life of Gibbons , I, pp. 486-546.

lower classes of the city. They spoke not as social investigators but as representatives. Theirs was not a movement of discovery and accommodation but a call for recognition and a demand for a more just share of the fruits of the society. Many Irish and German politicians prospered and in their success were as callous, corrupt, and conservative as the Presbyterian steel barons of Pittsburgh. But there were others who used their success to represent their constituents, men like Martin Lomasney of Boston or Charles F. Murphy of New York. These politicians joined with settlement-house workers, Protestant ministers, Jewish philanthropists, and union leaders to carry the important social legislation of the day through city councils, state legislatures, and Congress. By 1920, though the Church was full of conflicts between new Slavic and Italian ethnic groups and the established Irish and Germans and though many Catholics and priests were as doubtful as ever of the efficacy of reform and as fearful of liberalism and socialism, the success of millions of urban Catholics in moving into positions of comfort and power produced a sense of widespread personal optimism to reinforce the liberal tendencies of some political and religious leaders.[34]

For the Jewish immigrants, whose massive migration during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries made Jewish culture a permanent element in American life, the polarization between old-fashioned ghetto and village ways and modern urban life had commenced in Europe. German liberal Judaism and German and Russian anarchism and socialism traveled across the Atlantic to foster progressive movements among Jewish immigrants and the small Jewish communities that already existed in Eastern and Midwestern cities. There was probably not a reform effort in any big city in the United States after about 1880 that did not include at least one Jewish member. Indeed, the American version of the charitable tradition of the Jewish ghetto soon proved to be a major urban cultural bridge. Even in the face of rising anti-Semitism during these same years, Jewish philanthropists served on most metropolitan committees for child care, unemployment relief, and hospital and community fund drives, as well as on those directed to race relations and social legislation. Thus the Jewish philanthropist became a permanent element in metropolitan elite life.

[34] . Rudolph J. Vecoli, "Prelates and Peasants, Italian Immigrants and the Catholic Church," Journal of Social History , 2 (Spring 1969), 217-68; William V. Shannon, The American Irish , New York, 1963, pp. 114-63; McAvoy, History of the Catholic Church , pp. 263-390.

But for most Jews, the 1870-1920 decades were years of struggle with immigration and poverty. Just as the Irish and German slums had been symbols of poverty and exploitation in the earlier mixed commercial and industrial city, so the Jewish slum of the metropolis epitomized urban life of the "new immigration."[35] The tenements of New York's lower East Side, housing thousands of little sweatshops where Jewish immigrants labored on suits, overcoats, trimmings, dresses, and shirts, have become, thanks to liberal Jewish and Protestant writing, classic statements of the American immigrant experience. The raw exploitation of these industries was finally brought under control only by means of the organization and repeated strikes of the workers in these crafts and by the passage of restraining legislation.[36]

Because Jews located in the largest cities, where economic opportunities were then the most abundant, because they had a strong cultural imperative toward education at a time when the economy demanded the skills of formal education, and because their culture seemed so compatible with individualistic capitalism, Jewish immigrants rapidly took their places in the middle and upper levels of the class structure. Indeed, the story of the continuous struggles of these immigrant parents to provide their children with education, better jobs, and a better future has become today the controversial model of social and economic mobility. It is against this model that current arguments for cultural pluralism for Negroes, Chicanos, Indians, and old ethnic groups are being debated.[37]

Finally, the small black ghettos of Northern cities in these years laid the foundations for what would later become a revolution in black and white culture. Since job discrimination held so many Negroes in permanent poverty and race prejudice crowded blacks into expensive all-Negro communities, their liberalization and urbanization could not be borne on a wave of rising affluence and integration of the members of the culture,

[35] . Jacob Riis, How the Other Hall Lives , New York, 1890; Hutchins Hapgood, The Spirit of the Ghetto , New York, 1902; Abraham Cahan, The Rise of David Levinsky , New York, 1917; Moses Rischin, The Promised City: New York's Jews 1870-1914 , Cambridge, 1962.

[36] . Melvyn Dubofsky, When Workers Organize, New York City in the Progressive Era , Amherst, 1968, pp. 67-85.

[37] . Nathan Glazer and Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot , Cambridge, 1963, pp. 24-85; Lee Rainwater and William L. Yancey, The Moynihan Report and the Politics of Controversy , Cambridge, 1967, pp. 43-94; Mary G. Powers, "Class, Ethnicity, and Residence in Metropolitan America," Demography, 5 (1968), 447-48; Caroline Golab, "The Immigrant and the City: The Polish Experience in Philadelphia 1870 to 1920," Temple University Conference on the History of the Peoples of Philadelphia, April 2, 1971.

as had been the case for Catholics and Jews. Rather black culture had to accommodate itself to the fact of ghetto poverty and the capabilities of a small elite whose actions were narrowly circumscribed by the discrimination of the outside white society. Despite this confinement, the ghetto years of the first waves of migration from the South between 1890 and 1920 were a time of extraordinary cultural growth: the Negro churches adapted to the rush of migrants and participated in the general liberalization of Protestantism, while a parallel secular flowering established a modern definition of black Americans as a people with a unique art, history, literature, and music.

Before these migrations, when Negro clusters in Northern cities were small, the churches had served as community centers. They were the principal sources of black news, the cement that held clubs and lodges together, the bases for political action, and the links between the tiny black elite and the generality of low-paid black workers and servants. Rapid growth of black blocks to entire urban ghettos after 1890 inevitably destroyed such small-scale social unities. Though the web of discrimination hampered Negroes in a thousand ways, a small business and professional elite grew with the ghetto, thereby fragmenting the community's secular and religious leadership. Ministers had to share their role with doctors, teachers, newspapermen, government workers, politicians, and liquor and gambling operators, while at the same time large and successful congregations set themselves apart from the proliferation of store-front churches which sprang up to meet the needs of the new migrants. The extreme poverty of urban Negroes has forced black Protestantism to cope with far more extreme institutional divisions than its white counterpart, and it maintains to this day its character of a few large well-established churches surrounded by a sea of informal evanescent one-room congregations. Nevertheless all the features of white Protestantism prevail: a core belief and practice which allows blacks to move easily from one church to the next, the insistence among respectable families of every income that Sunday school is essential for children's education, the mixture of classes in each denomination, and the widespread participation in ancillary clubs, entertainments, and lectures.[38]

Thus the twentieth-century liberalization of black Protestantism

[38] . St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton, Black Metropolis, A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City , New York, 1945, pp. 412-23, 495-525.

went forward in the general climate of American religious practice, constrained only by the facts of ghetto poverty and the inescapable demand that ghetto Protestantism, like all ghetto institutions, serve the race. In the three decades after the Civil War, Negro ministers had participated in the fight to obtain the vote for Northern Negroes, to desegregate Northern city schools, and to seek full citizenship for the race. With the rise in the late nineteenth century of a new urban humanitarianism among Protestant and Jewish churchmen and philanthropists, the black elite absorbed and adapted the social gospel to its own race purposes. On the white side, slum missions gave way to settlement houses, social surveys, and reform politics, thereby building a new bridge toward the black leaders. The result was the formation of two new permanent organizations, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (1909) and the Urban League (1911), which embodied the spirit and technique of the new social consciousness. Although for a time in Southern cities white and black governing boards had to sit separately, with the spread of their chapters into every large city these new organizations formed a liberal interracial core which led the civil-rights campaigns throughout the nation until the 1960s.[39]

A unique cultural flowering also accompanied the 1890-1920 migrations and the growth of urban ghettos. In view of the poverty of Negro city dwellers and the small base of support which the elite could offer to black theater and arts, the Harlem Renaissance was a remarkable achievement of black liberation. A handful of poets, actors, dancers, painters, writers, and musicians fashioned a coherent heritage and modern image of a black American: a free man in the midst of oppression whose culture stretched back to Africa and Jerusalem. The discrimination against blacks in the entertainment, commercial-art, and publishing industries and their virtual exclusion from universities forced most Negro artists to depend upon the inadequate resources of the impoverished ghetto or to leave the black world altogether. As a result the cultural stream which the Harlem Renaissance opened early in this century was choked to a mere trickle. Only jazz, which could be nourished in the ghetto while meeting universal outside demand, flourished.[40]

[39] . Drake and Cayton, Black Metropolis , pp. 46-51; Arvarh E. Strickland, History of the Chicago Urban League , Urbana, 1966, pp. 6-35; Allan H. Spear, Black Chicago, The Making of a Negro Ghetto 1890-1920 , Chicago, 1967, pp. 54-89.

[40] . Johnson, Black Manhattan , pp. 182-230, 260-84; Harold Cruse, The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual , New York, 1967, pp. 11-95.

1920-

When the boom in the world market for agricultural products collapsed in 1921, the historic drive of Americans to cultivate their land on independent family farms collapsed with it. Troubles for the small farmer had been accumulating for years. Failure to secure credit for new machinery and new methods had driven many into mortgage foreclosure and tenancy, and competition from large-scale operators harried others. The discrepancy between what the ordinary farmer could earn by his labor and what his son or daughter could make in a city office or factory drew young people increasingly away from the land. Now as twenty years of depressed farm prices began, a term longer than anyone's savings or mortgage could sustain, farmers, white and black, gave up in droves and sought a new chance in the mill towns and cities. New Deal and subsequent agricultural legislation, far from helping the small farmer, brought new and highly productive irrigated land into competition and put capital into the hands of those who were already the most successful; the strong waxed rich and the weak were driven off the land.[41]

From Texas to Minnesota, thousands of Midwesterners gave up and moved to the Pacific; it was said that Los Angeles was Iowa transplanted. The textile, lumber, chemical, and petroleum industries gave employment to Southern farmers, while the continued expansion of the automobile industry in the Midwest absorbed many thousands from there and other regions. In this great exodus the rural American suffered all the exploitation and punishment of slum living that migrants from abroad suffered earlier. The shanty and trailer camps of Willow Run, thrown together for war workers, or the Appalachian North Side of Chicago today bear the marks of conflict between the rural style of life and that of the modern industrial city with its low pay, uncertain income, and harsh discipline.[42]

Beginning with World War II the blacks of the Southeast were finally able to participate fully in this national pattern, and they poured

[41] . Stanley Lebergott, "Tomorrow's Workers: The Prospects for the Urban Labor Force," in Warner, Planning for a Nation of Cities , pp. 124-40.

[42] . Harriette Arnow, The Dollmaker , New York, 1954; Todd Gitlin and Nanci Hollander, Uptown, Poor Whites in Chicago , New York, 1970.

out of the old Confederacy into Northern and Pacific cities.[43] There they have faced in our own time, as in previous periods, two special obstacles that have never confronted their white counterparts. Job prejudice consistently held down newcomers and older residents alike and excluded even the skilled and qualified from jobs commensurate with their abilities. Moreover, prejudice blocked Negroes from the traditional practice of one man's using his established position to make room for his friends, relatives, townsmen, and fellow ethnics. Employment restrictions closed down the historical process of urbanization whereby newcomers advanced either through job improvement or accumulation of property. Housing prejudice, far in excess of any that existed in respect to Jews or poor families of any sort, closed vast areas of the city to Negroes, and the black ghettos could often only expand by violence or by the purchase of housing at exorbitant prices. There had been ghettos and prejudice before in American cities, but the rapid growth of communities of Negro migrants in the North and the relentless job discrimination heightened the segregation. The outcome has been the emergence of an unprecedented situation in American cities: vast quarters are occupied exclusively by the members of a single race or origin.[44]

These special barriers against blacks made the Negro ghettos of the Northern cities a distinct departure from the slums where foreign immigrants or rural white natives lived. With housing choices and job access both severely curtailed, black ghettos became huge basins of poverty and low-income housing. They were very far from being "ports of entry," stopping places for the first years or the first generation, as twentieth-century Italian slums had been.[45] There the population repeatedly shifted as the more successful members followed jobs into industrial sectors or managed to purchase a house in a decent working-

[43] . These shifting patterns of urban migration among cities can be followed in Donald J. Bogue, Population Growth in Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas 1900-1950 , Housing and Home Finance Agency, Washington, 1953; and Karl E. and Alma F. Taeuber, Negroes in Cities , Chicago, 1965, pp. 139-44.

[44] . Sam Bass Warner, Jr., and Colin B. Burke, "Cultural Change and the Ghetto," Journal of Contemporary History , 4 (October 1969), 173-87; Stanley Lieberson, Ethnic Patterns in American Cities , New York, 1963, pp. 44-91; Taeuber and Taeuber, Negroes in Cities , pp. 31-68.

[45] . Humbert S. Nelli, Italians in Chicago 1880-1930, A Study in Ethnic Mobility , New York, 1970, pp. 22-54; Sister Mary F. Matthews, "The Role of the Public School in the Assimilation of the Italian Immigrant Child in New York City, 1900-1914," in Silvano M. Tomasi and Madeline H. Engel, The Italian Experience in the United States , New York, 1970, pp. 125-41.

class district. But newcomers kept pouring into the black ghettos and were kept there by the whites. Consequently our modern ghetto resembles the classic European one. Spatially and socially it is a microcosm of the metropolis, where the poor crowd into the oldest housing of the quarter and the skilled and more prosperous huddle together at the newer periphery.[46] All classes of blacks form an exploited community, as did the Jews in the ghettos of Europe, and they make up an isolated colony in the host society.

Furthermore, sizable black migration is a recent phenomenon, coinciding with the economic faltering of the old core cities in which blacks had to settle. Bad economic surroundings served as the unfortunate reinforcement to job prejudice, and both exacerbated the problem of the impoverishment of black migrants, of whom there were already a disproportionately large number as compared to white migrants.[47] The American Jewish ghetto had stemmed from specialization in the garment industry; the Irish, Italians, and Poles prospered in the construction trades attendant on the industrialization of booming cities. But blacks arrived to find both prejudice and an environment of low-paying, sluggish industries. This economic geography of the decentralizing metropolis creates for Negro migrants yet another hardship: the black ghetto is a residential place, not a mixed settlement of industry, commerce, and homes. Lacking skilled migrants or much employment of its own and blocked by the prejudice of bankers, insurance companies, wholesale outlets, and retailers, black capitalism can hope at most to serve the ghetto itself. Until the metropolis is opened, the skills, leadership, and capital of the black community are in the wrong place, at the wrong time, to participate in the profits of the growing metropolis.

Concurrently with urbanization, a number of events conspired to diminish the importance of overseas migration. Successive restrictions in this country and abroad prevented people from coming to the United States or leaving their own country. The United States excluded the Chinese in 1882, the Japanese in 1900, and then in a succession of laws in 1921, 1924, and 1929 set restrictive quotas that choked down the flow of population from Asia and Southern and Eastern Europe. The unemployment of the Great Depression followed and closed the United

[46] . Donald R. Deskins, Jr., "Race, Residence, and Workplace in Detroit, 1880 to 1965," Economic Geography , 48 (January 1972), 79-94.

[47] . John F. Kain, "Housing Segregation, Negro Employment, and Metropolitan Decentralization," Quarterly Journal of Economics , 82 (May 1968), 175-97.

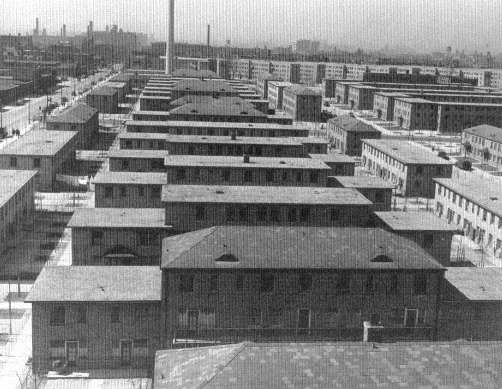

States to those who were seeking improvement over the economic conditions in advanced European countries. American immigration restrictions and those of Germany, Italy, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain trapped thousands of political prisoners, especially Jews, who by nineteenth-century practices would have sought asylum in the United States. Rejected by their own country and refused by ours, millions met their death in prisons and concentration camps.[48]