PART ONE—

NEXT OF KIN:

REMAKES AND HOLLYWOOD

One—

Remakes and Cultural Studies

Robert Eberwein

In this essay I propose a suggestion, based on an application of aspects of cultural studies, that is designed to provide a methodologically coherent approach to thinking about various kinds of remakes.[1] I urge a re -contextualization of the original and its remake, achieved by an analysis of conditions of spectatorship.[2]

It is difficult to know where to begin in theorizing remakes. It seems that many of the studies of remakes do not go much beyond a superficial point-by-point, pluses-and-minuses kind of analysis.[3] Often this kind of discussion employs a common strategy: the critic treats the original and its meaning for its contemporary audience as a fixity, against which the remake is measured and evaluated. And, in one sense, the original is a fixed entity.

But in another sense it is not. Viewed from the fuller perspective of cultural analysis over time, the original can—I am arguing that it must—be seen as still in process in regard to the impact it had or may have had for its contemporary audience and, even more, that it has for its current audience. A remake is a kind of reading or rereading of the original. To follow this reading or rereading, we have to interrogate not only our own conditions of reception but also to return to the original and reopen the question of its reception. Please understand that I am not arguing that a return to the original will necessarily yield a "new" meaning in the film that has hitherto been missed by shortsighted critics. Rather, I am arguing that a fresh return to the period may help us understand more about the conditions of reception at the time and, hence, offer us a fuller range of information for comparing the original and its audience with the remake and its audience. To demonstrate the point, I will use as my particular focus the original and remake of Invasion of the Body Snathchers (Don Siegel, 1956; Phil Kaufman, 1978). I have chosen this film largely because it has been remade

again by Abel Ferrara. I am sure that the most recent remake will evoke stimulating commentaries on the relation between itself and its predecessors, but I doubt that anyone writing about the new film will be able to position it fully in terms of its contemporary reception. And that is because a contemporary audience is fixed by its spatiotemporal restrictions. We are inside a particular historical and cultural moment that may in fact account for certain aspects of the film Ferrara made recently. It will remain for later critics to look back and speculate on the conditions of reception for the film in a way that I am convinced we really can't since we are inside the historical and cultural moment.

In a recent essay in Framework on Caribbean cinema, Stuart Hall makes some telling points that can serve to introduce the argument I want to make about our investigations of remakes as these both posit and depend on certain assumptions about audience reception. Specifically he addresses the concept of cultural identity as a construct emerging from the Caribbean cinema. But the applicability of his comments to assumptions about a shared cultural identity is pertinent to consideration of any cinema assumed to "reflect" the culture in which it is produced. According to Hall: "The practices of representation always implicate the positions from which we speak or write—the positions of enunciation . What recent theories of enunciation suggest is that, though we speak, so to say 'in our own name,' of ourselves and from our own experience, nevertheless who speaks, and the subject who is spoken of, are never exactly in the same place. Identity is not as transparent or unproblematic as we think. Perhaps . . . we should think . . . of identity as a 'production,' which is never complete, always in process, and always constituted within, not outside, representation" (68). Cultural identity "is not a fixed essence at all, lying unchanged outside history and culture" (71).

I am appropriating Hall's view of cultural identity and considering it in relation to the way we posit culturally inflected unity in originals and remakes. As you can tell, one of my basic concerns here is whether we can talk about remakes as if they and their audience were "lying unchanged, outside history and culture"—as if, in other words, interpretation can assume a fixed timeless cultural identity.

Some comments on the original and remakes of Invasion of the Body Snatchers will illustrate the point. Nora Sayre, for example, writes: "(In the Fifties, many believed that Communist governments turned their citizens into robots.) So the political forebodings of the period spilled over into science fiction, where subservience to alien powers and the loss of free will were so often depicted, and the terror of being turned into 'something evil' became a ruling passion. The amusing 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers did not perpetuate the social overtones—instead it concentrated on conformity and surrendering the capacity to feel, and few of the scenes

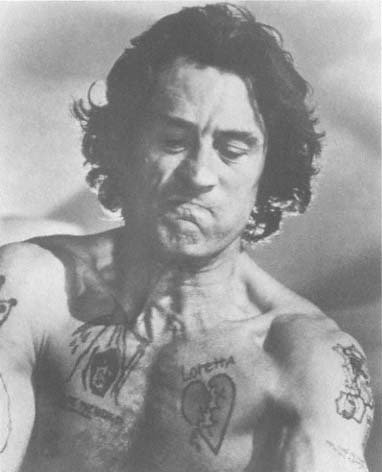

Figure 1.

Beware of huge pods found at night! A pod conceals its startling secret

in Don Siegel's original Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956).

had the impact of Kevin McCarthy's climax in the original, when he stood on a highway, screaming at passing trucks and cars, 'You fools, you're in danger . . .! They're after us! You're next! You're next!'" (184).

Richard Schickel's comment on the remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978) is equally relevant: "In its day, Invasion made a moving and exciting film. Among other things, it was a metaphorical assault on the times when, under the impress of McCarthyism and two barbecues in every backyard, the entire Lonely Crowd seemed to be turning into pod people. (See figure 1.) The remakers have missed that point, failing to update the metaphor so that it effectively attacks the noisier, more self-absorbed conformity of the '70s" (82).

Both Sayre and Schickel make what seem for a variety of reasons to be unwarrantable assumptions about audiences and reception that then become the basis of interpretive judgments. Each treats the original as having completed the acts of reflecting its culture and conveying its meanings once and for all. But this is a problematic position to maintain, particularly as a ground of critical judgment, because the position elides two questions: what

do we know of the specific audience for the first film? and what do we know of its multiple audiences over time? The position supposes that within a homogeneous audience locked in its own time and space—the time and space of the film's release—there had been cultural agreement and unanimity about interpretive questions when the film appeared.

Any film that survives will have audiences over time. A film that is remade encounters new audiences, individuals who might not have encountered the original if someone hadn't decided to remake the older film. The question of why later filmmakers appropriate earlier films is an issue deserving at least a brief digression at this point. Various suggestions have been made to account for the existence of remakes. These explanations range from the purely economic to the highly personal. For example, it is a critical commonplace that Hollywood studios have recycled films as a way of saving money by using properties to which they already hold the rights—hence remakes of older films. On one level, this explanation could be applied universally to account for all remakes, since no film is made in order to lose money.

But there are at least a couple of reasons why this explanation is too simple or at least incomplete. First, we have evidence that some directors with sufficient clout and economic support may remake a film for personal reasons. For example, Frank Capra explains why he remade Lady for a Day: "I wanted to experiment with retelling Damon Runyon's fairy tale with rock-hard non-hero-gangsters"—hence A Pocketful of Miracles (Silverman, 26). In addition, Franco Zeffirelli claims he remade The Champ (King Vidor, 1931; 1979) because he identified strongly with the family problems figured in the older film. He had seen it as a child and been moved. Having seen it more recently, he says: "'[T]he whole trauma came back, the whole syndrome of anguish.' He remembered that Richard Shepherd, an MGM executive, had invited him to make a movie in this country. 'I called him and said I wanted to do a remake to The Champ '" (Chase, 28).

Second, Harvey Greenberg has suggested even more complex reasons possible for wishing to remake a film, various forms of "Oedipal inflections" evident in different kinds of relationships between older and newer filmmakers: first, "unwavering idealization" in the faithful remake; second, "the remaker, analogous to a creative resolution of childhood and adolescent Oedipal conflict, eschews destructive competition with the maker, taking the original as a point of useful, unconflicted departure"; third, "the original, as signet of paternal potency and maternal unavailability/refusal, incites the remaker's unalloyed negativity"; and, fourth, "the remaker, simultaneously worshipful and envious of the maker, enters into an ambiguous, anxiety-ridden struggle with a film he both wishes to honor and eclipse." The latter is the "contested homage" Greenberg sees at work in Steven Spielberg's Always (115ff.).

In addition, we can think of one remake that is the product of neither economics nor psychoanalytic conflict. As Lea Jacobs has explained, Universal had hoped to re-release Back Street (John Stahl, 1932) in 1938, but, because it ran afoul of the Production Code Administration, headed by Joe Breen, the studio ended up having to remake the film (Robert Stevenson, 1941): "[T]he film had been . . . criticised by the reform forces at the time of its original release; in particular, it had been attacked by Catholics connected with the Legion of Decency. The story . . . was said to generate sympathy for adulterers and to undermine the normative ideal of marriage as monogamous. When Breen argued against a re-release of the 1932 version, Universal agreed to do a remake" (107).

It is useful to consider Phil Kaufman's stated reasons for wanting to remake Invasion of the Body Snatchers in light of this information:

In 1956, the science-fiction consciousness of the public was limited, and now it's greatly expanded, so you could deal with certain things in different ways. . . . There were a lot of articles coming to my attention about how we were being bombarded from outer space, saying that diseases are coming from outer space. . . . There were political overtones to the original film, and there are two sides on this. What was the original saying? Was it anti-Communist? Was it anti-anti-Communist? I don't know the answer to that. It's interesting to examine the original film both ways, because both theories seem to make sense. Obviously those political overtones don't apply to our film. . . . I also feel that paranoia or fear is a very important thing. I don't think this film would have been worthy of a remake during the period of the Vietnam war, because at that time there was a high consciousness about where we were. The fears hanging over everyone's heads—particularly young people's—gave them a sense of mortality. . . . I think that in the last couple of years, we've been losing that sense of mortality. Fear is very valuable in a time of complacency (Farber, 27).

In addition, Kaufman says, "It seems to me . . . that this is a perfect time to restate the message of Body Snatchers . . . . We were all asleep in a lot of ways in the Fifties, living conforming, other-directed types of lives. Maybe we woke up a little in the Sixties, but now we've gone back to sleep again. We've taken some of the things that were expressed about the original film—that modern life is turning people into unfeeling, conforming pods who resist getting involved with each other on any level—and we're putting them directly into the script" (Freund, 23). (See figure 2.)

Interestingly, in none of Kaufman's comments, or in the reviews cited above, do we get anything that addresses the historical-cultural moment when the original film actually appeared. It was released without any acknowledgment in the New York Times (advertising or reviews) at the end of February 1956. There are very few reviews that Albert LaValley has been able to assemble in his invaluable edition of the script and commentary. In

Figure 2.

A pod person slumbers in Phil Kaufman's Invasion of the

Body Snatchers , the 1978 remake.

subsequent years, as far as I have been able to determine, no one has fully come to terms with the moment of the film's release in regard to the audience and the country receiving it. But, as George Lipsitz, one of the major American proponents of cultural studies, reminds us in a discussion of other works, any film "responds to tensions exposed by the social moment of its creation, but each also enters a dialogue already in progress, repositioning the audience in regard to dominant myths" (169). Equally pertinent is Michael Ryan's observation: "The 'meaning' of popular film, its political and ideological significance, does not reside in the screen-to-subject phenomenology of viewing alone. That dimension is merely one moment in a circuit, one effect of larger chains of determination. Film representations are one subset of wider systems of social representation (images, narratives, beliefs, etc.) that determine how people live and that are closely bound up with the systems of social valorization or differentiation along class, race and sex lines" (480).

I want to talk about the dialogue already in progress when the original emerged, with the hope of putting us in closer contact with the audience that experienced the film. First, I want to clarify somewhat more fully

the question of the communist menace. By the time the film appeared, Senator Joseph McCarthy, whose attack on communists is consistently used to interpret the film's meaning (anti-communist? anti-anti-communist?), had already started to lose power. Joseph Welch's stinging condemnation of him had occurred in 1954. In 1955, the year that Invasion of the Body Snatchers was being made, while there continued to be investigations of communists, some of them proceeding from McCarthy, news accounts reveal a partial unraveling of the charges and sentences that had resulted from the activities of McCarthy and Roy Cohn. As a matter of fact, in the very months that the film was being made (March 23 to April 18, 1955), the convictions of two men were reversed on the grounds that one Harvey M. Matusow had admitted to lying when he said they were communists. Matusow claimed he had been coached by Roy Cohn. The latter was exonerated of that charge. Still, in the context of a year when other convicted communists were being released (some to be retried) and when, according to Facts on File , "the Eisenhower administration, reacting to criticism of its employee security program, revised its procedure to insure that accused Govt. workers received 'fair & impartial treatment' at the hands of Govt.," it is clear that the overwhelming period of paranoia and the domination of McCarthy and Cohn had started to ease significantly (Facts on File , March 3–9, 1955: 75. Also February 24–March 2; March 10–16; April 21–27). Thus, we need to be careful about the extent to which we: 1) attribute a particular mind-set to a contemporary audience confronting a film supposedly illustrating the communist menace (whether from the left or the right); 2) use this mind-set to fix the film's meaning; and 3) criticize a remake for failing to reproduce it.

There are two historically relevant matters that can be advanced as having more than a casual relevance to the contemporary audience. The first involves what for want of a better term I will call the discourse of medicine. Peter Biskind talks about the treatment of doctors generally in right-wing films but hasn't fully explored the following with reference to Invasion (60–61). In 1954, Dr. Jonas Salk had discovered a vaccine that would apparently stop polio. The vaccine was tested in 1955 and put to use that year. On February 6, 1956 (a few weeks before the release of Invasion ), Salk and his predecessors who worked to develop the vaccine were honored by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. The citation is worth quoting, particularly in light of cold-war rhetoric: "A community needed a bell tower to warn its people against attack. Everyone helped to build it, and the whole was greater than the sum of its parts. When it was finished, the feeling of gratitude of each man for his neighbor, for what each had contributed, was showered upon but one—and he was among the last to contribute. But all knew that the end could not have come without the beginning and without all that had transpired in between" ("Salk Award," 74). Jonas

Salk was one of two doctors whose status approached that of the venerated. The other was Paul Dudley White, President's Dwight Eisenhower's personal physician and the person honored not only for helping Eisenhower pull through his heart attack but also for having started to change the health habits of Americans. Dr. White's status as personal physician and as national spokesperson for health was of particular significance at the moment the film was being released, because the nation was poised to hear whether Eisenhower would run again for election. There had already been considerable campaign activity among Democratic candidates, particularly between Estes Kefauver and Adlai Stevenson, who were seeking the nomination. It was assumed that Eisenhower's decision, when it came, would be predicated on Dr. White's estimate of his health and fitness to run. The week before the film opened, White and the medical advisers had said he was "able"; the title of an article in Life for February 27, 1956, on the matter was: "Doctors Say He's Able—Is He Willing?" (38–39).

Thus at the point of the film's appearance, one can see a valorization almost approaching the hagiographic of two doctors: Salk, who had saved the children from attack; and White, who had saved the president and was helping to change physical behavior in the nation's citizens. The latter's work had an inescapably political dimension, given his association with administrative and hence political stability.

In addition, there was evidently strong support for the medical profession in general. Time reported on a survey done by the American Medical Association: "To no one's surprise, the A.M.A. concluded that doctors stand comfortingly high in public esteem. Only 82% of the 3,000 people polled have a regular family physician, but of those who do, 96% think well of him" ("Patients Diagnose Doctors," 46). That same week, the magazine reported on a training program developed at the Menninger Psychiatric Clinic in Topeka, Kansas, in which the Menninger brothers counseled various business leaders and managers in ways of using "psychology and psychiatry . . . to help them with their problems" in the workplace ("Psychiatry for Industry," 45).

In such a historical and cultural context, it is worthwhile to consider the possible impact of Invasion of the Body Snatchers , specifically the impotency of those associated with the medical discourse in the film. The psychiatrist Danny Kaufman (Larry Gates), the family doctor Ed Pursey (Everett Glass) who delivered Becky, and the nurse Sally (Jean Willes) are all taken over by the pods. It is Sally who is conducting the transformation of her own baby when Dr. Miles Bennell (Kevin McCarthy) spies on her home. Only in the narrative frame added after previews of the film is Miles restored to viability within the medical community; this occurs when Dr. Bassett (Richard Deacon) and Dr. Hill (Whit Bissell), another psychiatrist, begin to believe his story after hearing of the truck accident and the cargo

of pods. My point is that such a unilateral and comprehensive presentation of medicine as succumbing to an alien force (involving nursing, general practice, and psychiatry) can be imagined to have had some resonance with the audience, but in a way that doesn't involve conformity or conspiracy.

An even more significant historical-cultural consideration I want to point out has to do with the events of February 1956 as they pertained to civil rights. Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, and a subsequent ruling in 1955 in which the phrase "with all due deliberate speed" was used in reference to public education, were very much on the collective minds of the citizens in 1956. Early in February, Miss Autherine Lucy had entered the University of Alabama in Montgomery under court order. After two calm nights (she was not permitted to stay in the dormitory), various demonstrations erupted, including cross burnings. She was dismissed from the institution by the trustees in order to insure harmony. This action occasioned different kinds of agitated reactions. Some students protested the trustees' action. Democrats campaigning for the presidential nomination were asked what they would do to enforce the court decree if they were president. At the same time, on February 21, "115 persons were indicted by a county grand jury . . . in Montgomery, Ala. . . . on charges of instigating a Negro mass boycott of City Line buses. . . . The boycott began Dec. 5, 1955, after Mrs. Rosa Parks, a Negro, was fined $14 for refusing to give up her seat" (Facts on File , February 15–21: 61). The following week, a Gallup poll reported that "Southern whites disapproved the Supreme Court's school desegregation ruling by a 80%–16% majority" (Facts on File , February 22–28, 1956: 68). In the first week of the film's release, Life carried an essay by Nobel Prize winner William Faulkner, "A Letter to the North," in which he defends the position of going slowly in the integration process. Although he says segregation is an "evil," "I must go on record as opposing the forces outside the South which would use legal or police compulsion to eradicate that evil overnight" (51). He concludes by asserting "that 1) Nobody is going to force integration on [the Southerner] from the outside; 2) [t]hat he himself faces an obsolescence in his own land which only he can cure: a moral condition which not only must be cured but a physical condition which has got to be cured if he, the white Southerner, is to have any peace, is not to be faced with another legal process or maneuver, every year, year after year, for the rest of his life" (52).

The use of language couched in reference to cures and illness is significant. A month earlier, in an article entitled "South Rises Again in Campaign to Delay Integration," Life had run a picture of a Pontiac automobile carrying a Confederate flag and a banner taped to the side: "Save Our Children from the Black Plague" (22–23). And the previous year, according to William J. Harvie, in testimony before the Supreme Court, a Virginia attorney working for delay in integration said: "Negroes constitute 22 percent of

the population of Virginia . . . but 78 percent of all cases of syphilis and 83 percent of all cases of gonorrhea occur among the Negroes. . . . Of course the incidence of disease and illegitimacy is just a drop in the bucket compared to the promiscuity[;] . . . the white parents at this time will not appropriate the money to put their children among other children with that sort of background" (63).

In addition, according to the New York Times , during that month there were renewed instances of states such as Georgia and Mississippi introducing "nullifying" bills and "interposition" bills. The former type of bill simply denies the application of federal rulings to an individual state; the latter involves states enacting laws to defend their own jurisdictions by countering federal legislation ("Miss Lucy v. Alabama," 1; "Georgia Adopts 'Nullifying' Bill," 16). In addition, there was movement to "abolish public schools, create gerrymandered school districts and set up special entrance requirements" ("School Integration Report," 7).

All this is offered not to say that Invasion of the Body Snatchers contains a previously undiscovered allegory about racism but, rather, to suggest that we ought to remember that the film entered a dialogue, to use Lipsitz's phrase, of considerable tension. In this regard, it is interesting to consider several scenes from the original in which the action and language seem pertinent.

In the first of these scenes, Miles, suspecting that a gas station attendant who had earlier serviced his car may be one of the invaders, stops his car and discovers two pods hidden in the trunk. He pulls them out and sets them on fire. The camera lingers on the flames as they envelop the pods. Burning of alien forces at night in a way that emphasizes the flames against the darkness might well have reminded contemporary audiences of the cross burnings that had recently occurred.

Second, as Miles and Becky (Dana Wynter) watch unobserved from his office, townspeople gather in the square while the pods are being distributed to trucks that will carry them to various communities beyond Santa Mira. As he sees the full implication of the spread of the pods and the infiltration of the aliens into neighboring communities, Miles describes the situation to Becky in terms of a "malignant disease spreading throughout the country."

Third, during the frenzied sequence on the highway, Miles tries to stop motorists and warn them. Specifically (in a shot in which he virtually addresses the camera) he warns: "Those people are coming after us. They're not human. You fools, you're in danger. They're after you, they're after all of us. Your wives. Your children." It is hard not to see a connection between the film's depiction of a threatening, destabilizing force from within the society, characterized in terms of disease, taking over lives, and threatening wives and children, and the current discourse going on in the country in

which individual states tried to avoid what was perceived as a similarly destabilizing force, one characterized as a disease.

I make no claim that this information about the context of reception for the 1956 Invasion will help us understand the 1978 film any better. But it may help to define the differences between the two films somewhat more finely and in a way that goes beyond what I submit has not been sufficiently complete. What's at issue is a cultural version of Michel Foucault's episteme or what in another context Ann Kaplan has called the "semiotic field" of a work (41). As scholars and critics making comparative evaluations, we enrich our work to the extent that our positioning of the original in relation to the remake comes to terms with the forces and dialogues that shaped the works as well as those into which it entered. In fact, with this kind of comparative approach, we may find ourselves better positioned to comment on the relation between original and remake.[4]

The remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers was released December 22, 197.. Within the month, events occurred that could not have been anticipated in any way by the filmmakers but that provide a grim background for its reception. First was the discovery of the mass suicides led by Jim Jones at the People's Temple of Jonestown, Guyana. Pictures of the more than nine hundred suicides appeared in newspapers and, in color, in magazines like Time and Newsweek . Reports of the suicide made it clear that some of the victims were forced to participate. According to Facts on File, "As for the dissenters, some appeared to have been browbeaten into drinking the poison and others appeared to have been murdered by zealous cult members. Guyanese sources told the New York Times Dec. 11 that at least 70 of the bodies found at Jonestown bore fresh injection marks on their upper arms. The marks presumably showed that the poison had been injected into these victims by others, since it was very difficult for a person to inject himself in that part of the body" (Facts on File, December 15, 1978: 955).

Such information and pictures must have resonated in those members of the audience aware of it who were watching the weirdly charismatic psychiatrist Dr. David Kibner (Leonard Nimoy) inject Matthew Bennell (Donald Sutherland) and Elizabeth Driscoll (Brooke Adams) with a "light sedative" that would cause them to sleep and, subsequently, to die as they were taken over by the aliens. The international reaction to the horribly disturbing mass suicide had its counterpart in the national response to the news that, within a few weeks, two teenagers committed suicide in a suburb in New Jersey; they were "the third and fourth Ridgewood, N.J., youngsters to die by their own hands in the past 18 months." One explanation offered was that attention paid to the Jonestown disaster may have triggered the recent suicides, but others, according to Time, "[saw] a deeper malaise," including school pressures and family difficulties ("Trouble in Affluent Suburb," 60).

Ironically, the December 4 story about Jonestown included a quotation from San Francisco Mayor George Moscone, who, according to Time, "received important help from Jones in his close 1975 election [and had] appointed him to the city's housing authority in 1976. (Said the mayor about last week's horror: 'I proceeded to vomit and cry.')" ("Messiah from the Midwest," 27). Within the week, Moscone was dead, having been shot along with Harvey Milk by Dan White. In a creepy coincidence, the film is set in San Francisco and includes a scene in which Matthew seeks Kibner's help in reaching the mayor by phone. As far as I have been able to determine, the association of the suicides and murders, of Jones, Moscone, and Milk, and San Francisco, and the turbulent atmosphere of death in the month of December seem not to have entered into contemporary reviews of the film. Indeed, the opposite seems to be the case if Pauline Kael's laudatory review is examined. She notes: "The story is set in San Francisco, which is the ideally right setting because of the city's traditional hospitality to artists and eccentrics. . . . San Franciscans often look shell-shocked. . . . The hipidyllic city, with its ginger-bread houses and its jagged geometric profile of hills covered with little triangles and rectangles, is such a pretty plaything that it's the central character" (48).

Our own period has recently seen a revival of interest in conspiracy theories in regard to the assassination of John F. Kennedy because of the interest generated in conjunction with Oliver Stone's film (JFK, 1991). The audience for Invasion of the Body Snatchers during the last week of 1978 and the beginning of 1979 was learning that the House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations "concluded Dec. 30 that President John F. Kennedy 'was probably assassinated as a result of conspiracy' in 1963. . . . The committee also said that on the basis of circumstantial evidence 'there is a likelihood' that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was slain as a result of conspiracy. . . . The findings came at the end of the committee's $5.8 million, two-year inquiry into the assassinations of the two leaders. . . . The committee flatly stated that none of the U.S. intelligence agencies—the Central Intelligence Agency, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Secret Service—were involved in the Kennedy murder. The three agencies cleared were, however, criticized for their failings during the assassination and in the investigations after. The Justice Department was also attacked for its direction of the FBI probe" (Facts on File, December 31, 1978: 1002). Such information could well have hit a collective nerve in the audiences watching the futile attempts of Matthew Bennell and his friends. It's not that Kaufman gives any evidence of wanting to build in considerations of assassination conspiracy theories; rather, the film, with its frightening depiction of a conspiracy involving the police, the municipal government, and the secret service appears at a time when a major committee is raising the possibility of conspiracies and denying that the highest government agencies

are involved. The threat of conspiracy in the remake seems, from our perspective, to have even more potential relevance to its audience in 1978 than the already fading threat of a communist conspiracy had for the audience of 1956.

Another dimension of the semiotic field worth noting concerns the pods themselves. Certainly one of the most disturbing scenes in the films occurs when we watch the creatures reproducing while Matthew sleeps. Kaufman examines the creatures with uncompromising (and unnerving) scrutiny as they emerge struggling from their pods, swathed in weblike mucus and uttering little cries. After being awakened by Nancy Bellicec (Veronica Cartwright), Miles uses a spade to attack the pods and, in one particularly gruesome shot, is seen splitting open the head of the one that resembles him.

In this scene the film enters a dialogue about abortion that was raging then and is even more violent now. Nothing that Kaufman has said even hints at any self-conscious imposing of a thesis on abortion into the film. Just as I linked the earlier film to civil rights, I here try to contextualize the images in terms of the audience's historical and cultural position in relation to the controversy. What is clear to me is that such images entered a semiotic field in which the legal and medical status of the fetus had already been hotly debated. In 1978, there had been several cases nationally in which "consent" agreements had included provisos that women seeking abortions had to view photographs of fetuses or be given descriptions of them by doctors. According to Facts on File, the law in Louisiana "required the doctor to describe 'in detail' the characteristics of the fetus, including 'mobility, tactile sensitivity, including pain, perception or response, brain and heart function, the presence of internal organs and the presence of external members'" (September 29, 1978: 743).

There was also legal consideration of the fetus's ability to withstand a saline abortion, most immediately in connection with the trial of Dr. William Waddill, a California physician accused of having strangled a twenty-eight-to thirty-one-week-old infant after it survived an abortion (Lindsay, 18). Audiences watching the film and Bennell's "murder" of his double might well have been affected by the abortion controversy, particularly since they had watched the character kill something that, recently emerged from its pod, was more "alive" than "dead."[5]

I am grateful to Lucy Fischer for suggesting that another dialogue in which the film can be seen engaging concerns in vitro fertilization, a medical phenomenon that had occurred for the first time earlier in 1978. In July of that year in England, Drs. Patrick Steptoe and Robert Edwards succeeded in effecting the conception of a child for Lesley and Gilbert John Brown ("British Awaiting Birth," 1). That same month, a much less happy case of in vitro fertilization was reported. The John Del Zio family was suing the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center, charging that Dr. Raymond L.

Vande Wiele "deliberately destroyed" the embryo produced in 1973 at the hospital ("Childless Couple Is Suing Doctor," 26). One concern raised during the trial by lawyers defending Columbia University was that the experiment's outcome was uncertain: "[The Del Zio's] physicians, the lawyer said, had no way of knowing whether their efforts would produce a 'monster birth' or a normal child" ("2 Charge 'Jealous' Doctor," 9). Shortly after this scene, Kaufman's film does in fact reveal a monster effected by this process. As a result of a partial aborting of the pod birth process, a dog acquires the head of the Union Square singer seen earlier in the film. Again, an audience in 1978 could reasonably be expected to have a certain amount of exposure to this medical information about a different kind of birth process, one in which there is a fear of something going wrong.

I want to conclude by quoting George Lipsitz again. He speaks of "sedimented historical currents" and of "sedimented networks and associations" that are more than merely intertextual references. His comment seems pertinent to our consideration of remakes and their originals: "The presence of sedimented historical currents within popular culture illumines the paradoxical relationship between history and commercialized leisure. Time, history, and memory become qualitatively different concepts in a world where electronic mass communication is possible. Instead of relating to the past through a shared sense of place or ancestry, consumers of electronic mass media can experience a common heritage with people they have never seen; they can acquire memories of a past to which they have no geographic or biological connection. The capacity of electronic mass communication to transcend time and space creates instability by disconnecting people from past traditions, but it also liberates people by making the past less determinate of experiences in the present" (5). This is true, but I would add that we have to work at this by reconstructing as much as possible the historical contexts, just as someone years hence will try to recover ours.

Kinds of Remakes:

A Preliminary Taxonomy

1. a) A silent film remade as a sound film: Ben Hur (Fred Niblo, 1926, and William Wyler, 1959); b) a silent film remade by the same director as a sound film: Ernst Lubitsch's Kiss Me Again (1925) and That Uncertain Feeling (1941) or Cecil B. DeMille's The Ten Commandments (1923 and 1956); c) a major director's silent film remade as a sound film by a different major director: F. W. Murnau's Nosferatu (1922) and Werner Herzog's Nosferatu, the Vampire (1979).

2. a) A sound film remade by the same director in the same country: Frank Capra's Lady for a Day (1936) and A Pocketful of Miracles (1961); b) a sound film remade by the same director in a different country

in which the same language is spoken: Alfred Hitchcock's The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934, England, and 1954, United States); c) a sound film remade by the same director in a different country with a different language: Roger Vadim's And God Created Woman . . . (1957, France, and 1987, United States).

3. A film made by a director consciously drawing on elements and movies of another director: Howard Hawks's and Brian DePalma's Scarface (1932 and 1983); Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo (1959) (and Rear Window [1955] and Psycho [1960]), and DePalma's Obsession (1976), Body Double (1984), and Raising Cain (1992).

4. a) A film made in the United States remade as a foreign film: Diary of a Chambermaid by Jean Renoir (1946, France) and Luis Buñuel (1964, France); b) a film made in a foreign country remade in another foreign country: Yojimbo (Akira Kurosawa, 1961) and A Fistful of Dollars (Sergio Leone, 1964); c) a foreign film remade in another foreign country and remade a second time in the United States: La Femme Nikita (Luc Besson, 1990, France), Black Cat (1992, Hong Kong) (thanks to Scott Higgins), and Point of No Return (John Badham, 1993); d) a foreign film remade in the United States: La Chienne (Jean Renoir, 1931) and Scarlet Street (Fritz Lang, 1945) and Breathless (Jean-Luc Godard, 1960, and Jim McBride, 1983).

5. a) Films with multiple remakes spanning the silent and sound eras: Sadie Thompson (Raoul Walsh, 1928), Rain (Lewis Milestone, 1932) and Miss Sadie Thompson (Curtis Bernhardt, 1953); b) films remade within the silent and sound eras as well as for television: Madame X (Lionel Barrymore, 1929 [the third silent remake of the silent film]; Sam Wood, 1937; David Lowell-Rich, 1966 [the Lana Turner version]; and, for television, Robert Ellis Miller, 1981 [with Tuesday Weld]).

6. a) A film remade as television film: Sweet Bird of Youth (Richard Brooks, 1962, and Nicholas Roeg, 1989); b) a film remade as a television miniseries: East of Eden (Elia Kazan, 1955, and Harvey Hart, 1981); c) a television series remade as a film: Maverick (Richard Donner, 1994) and The Flintstones (Brian Levant, 1994).

7. a) A remake that changes the cultural setting of a film: The Big Sleep (Howard Hawks, 1946, United States, and Michael Winner, 1978, Great Britain); b) a remake that updates the temporal setting of a film: Murder, My Sweet (Edward Dmytryk, 1944) and Farewell My Lovely (Dick Richards, 1975); A Star Is Born (William Wellman, 1937, George Cukor, 1954, and Frank Pierson, 1976); Out of the Past (Jacques Tourneur, 1948) and Against All Odds (Taylor Hackford, 1984); c) a remake that changes the genre and cultural setting of the film: The Lives of a Bengal Lancer (Henry Hathaway, 1935) re-

made as a western, Geronimo (Paul H. Sloane, 1939); the western High Noon (Fred Zinnemann, 1954) remade as the science fiction film Outland (Peter Hyams, 1981).

8. a) A remake that switches the gender of the main characters: The Front Page (Lewis Milestone, 1931); His Gal Friday (Howard Hawks, 1941); b) a remake that reworks more explicitly the sexual relations in a film: William Wyler's These Three (1936) and The Children's Hour (1961); The Blue Lagoon (Frank Launder, 1949, and Randal Kleiser, 1980).

9. A remake that changes the race of the main characters: Anna Lucasta (Irving Rapper, 1949, with Paulette Goddard; Arnold Laven, 1958, with Eartha Kitt).

10. A remake in which the same star plays the same part: Ingrid Bergman in the Swedish and American versions of Intermezzo (Gustav Molander, 1936, and Gregory Ratoff, 1939); Bing Crosby in Holiday Inn (Mark Sandrich, 1942) and Holiday Inn (Michael Curtiz, 1954).

11. A remake of a sequel to a film that is itself the subject of multiple remakes: The Bride of Frankenstein (James Whale, 1975) and The Bride (Frank Roddam, 1985).

12. Comic and parodic remakes: Frankenstein (James Whale, 1931) and Young Frankenstein (Mel Brooks, 1954); Strangers on a Train (Alfred Hitchcock, 1951) and Throw Mamma from the Train (Danny DeVito, 1987).

13. Pornographic remakes: Ghostbusters (Ivan Reitman, 1984) and Ghostlusters (1991); Truth or Dare (Alex Kashishian, 1991) and Truth or Bare (1992) (thanks to Peter Lehman).

14. A remake that changes the color and/or aspect ratio of the original: The Thing (Christian Nyby, 1951, black-and-white; John Carpenter, 1982, color and Panavision); Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Don Siegel, 1956, black-and-white and Superscope; Phil Kaufman, 1978, color and 1.85 to 1 aspect ratio).

15. An apparent remake whose status as a remake is denied by the director; Michelangelo Antonioni's Blow-Up (1966) and Francis Ford Coppola's The Conversation (1974).

This taxonomy doesn't cross-reference films. Clearly, some could be put in more than one category. The Big Sleep, for example, updates the temporal and cultural settings. In addition, the list doesn't address any number of relevant production and economic aspects: the role of the star as an element in developing the remake (Barbra Streisand and the 1976 A Star Is Born ); variations in advertising, marketing, and distribution practices from period to period, genre to genre, country to country; historical data about the studios' decisions on remaking; comparative financial data on the origi-

nal and remake; issues of acquiring rights; distinguishing among the major and minor studios (e.g., an MGM remake of an MGM picture? a United Artists remake of an Allied Artists picture?); and epochal analyses of remaking practices—for example, comparative data regarding the number of remakes in the period of "classical Hollywood cinema" as opposed to during the sixties and later periods.[6]

Even more problematic, the taxonomy itself doesn't address the issue of adaptation: are there any films in the various categories that can claim a common noncinematic source? If so, is it correct to call a film a remake or a new adaptation (e.g., Madame Bovary, Vincente Minnelli, 1949; Claude Chabrol, 1991)? Are there stages left out between the original and remake, as occurs for example when a play intervenes between the original and the remake (e.g., The Wiz )?

Works Cited

Biskind, Peter. Seeing Is Believing: How Hollywood Taught Us to Stop Worrying and Love the Fifties. New York: Pantheon Books, 1983.

"British Awaiting Birth of Baby Conceived in Laboratory Process." New York Times, 12 July 1978, sec. 1, pp. 1, 13

Chase, Donald. "The Champ: Round Two." American Film 3, no. 9 (July–August 1978): 28.

"Childless Couple Is Suing Doctor." New York Times, 16 July 1978, sec. 1, p. 26.

"Doctors Say He's Able—Is He Willing?" Life, 27 February 1956, 38–39.

Doherty, Thomas. "The Fly." Film Quarterly 40, no. 3 (spring 1987): 38–41; "The Blob." Cine-Fantastique 19, no. 1–2 (January 1989): 98–99.

Druxman, Michael B. Make It Again, Sam: A Survey of Movie Remakes. Cranbury, N.J.: A. S. Barnes, 1975.

Facts on File Yearbook 1955. Vol. 15. New York: Facts on File, 1956.

Facts on File Yearbook 1956. Vol. 16. New York: Facts on File, 1957.

Farber, Stephen. "Hollywood Maverick." Film Comment 15, no. 1 (January–February 1979): 26–31.

Faulkner, William. "A Letter to the North." Life, 5 March 1956, 51–52.

Freund, Charles. "Pods over San Francisco." Film Comment 15, no. 1 (January–February 1979): 22–25.

"Georgia Adopts 'Nullifying' Bill." New York Times, 14 February 1956, sec. 1, p. 16.

Greenberg, Harvey Roy. "Raiders of the Lost Text: Remaking as Contested Homage in Always, " this volume, 115–130.

Hall, Stuart. "Cultural Identity and Cinematic Representation." Framework 36 (1989): 68–81.

Harvie, William J. III. From Brown to Bakke: The Supreme Court and School Integration, 1954–1978. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Jacobs, Lea. "Censorship and the Fallen Woman Cycle." In Home Is Where the Heart Is: Studies in Melodrama and the Woman's Film, edited by Christine Gledhill, 100–112. London: BFI Books, 1987.

Kael, Pauline. "Pods." The New Yorker, 25 December 1978, 48, 50–51.

Kaplan, E. Ann. "Dialogue." Cinema Journal 24, no. 2 (winter 1985): 40–41.

Kellner, Douglas. "David Cronenberg: Panic Horror and the Postmodern Body." Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory 13, no. 3 (1989): 89–101.

LaValley, Albert J., ed. Invasion of the Body Snatchers. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1989.

Lindsay, Robert. "Coast Doctor's Murder Trial Draws Abortion Foes' Interest." New York Times, 10 April 1978, sec. 1, p. 18.

Lipsitz, George. Time Passages: Collective Memory and American Popular Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1990.

"Messiah from the Midwest." Time, 4 December 1978, 22, 27.

Milbauer, Barbara. The Law Giveth: Legal Aspects of the Abortion Controversy. New York: Atheneum, 1983.

Milberg, Doris. Repeat Performances: A Guide to Hollywood Movie Remakes. Shelter Island, N.Y.: Broadway Press, 1990.

"Miss Lucy v. Alabama." New York Times, 12 February 1956, sec. 4, pp. 1–2.

Nowlan, Robert A., and Gwendolyn Wright Nowlan. Cinema Sequels and Remakes, 1903–1987. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland and Co., 1989.

"Patients Diagnose Doctors." Time, 13 February 1956, 46.

"Psychiatry for Industry." Time, 13 February 1956, 45.

Rubin, Eva R. Abortion, Politics and the Courts: Roe v. Wade and Its Aftermath. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1982.

Ryan, Michael. "The Politics of Film: Discourse, Psychoanalysis, Ideology." In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, 477–486. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988.

"Salk Award." Time, 6 February 1956, 74.

Samuels, Stuart. "The Age of Conspiracy and Conformity: Invasion of the Body Snatch-

ers. " In American History/American Film: Interpreting the Hollywood Image, edited by John E. O'Connor and Martin A. Jackson, 203–217. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1979.

Sayre, Nora. "Watch the Skies." In LaValley, 184.

Schickel, Richard. "Twice-Told Tales." Time, 25 December 1978, 82.

"School Integration Report: The Situation in 17 States." New York Times, 19 February 1956, sec. 4, p. 7.

Silverman, Stephen M. "Hollywood Cloning: Sequels, Prequels, Remakes, and Spin-Offs." American Film 3, no. 9 (July–August 1978): 24–27, 29.

Simonet, Thomas. "Conglomerates and Content: Remakes, Sequels, and Series in the New Hollywood." Current Research in Film 3 (1987): 154–162.

"South Rises Again in Campaign to Delay Integration." Life 6 February 1956, 22–23.

"2 Charge 'Jealous' Doctor Killed 'Test-Tube Baby.'" New York Times, 18 July 1978, sec. 2, p. 9.

"Trouble in Affluent Suburb." Time, 25 December 1978, 60.

Two—

Algebraic Figures:

Recalculating the Hitchcock Formula

Robert P. Kolker

Alfred Hitchcock was a director of elegant solutions. His best films are well-tuned cinematic mechanisms that drive the elements of character, story, and audience response with a calculated construction that creates, anticipates, yet never quite resolves the viewer's desire to see and own the narrative. Hitchcock's films make us believe that we understand everything even while they leave us unsettled about what we have seen and unsure about our complicity in the event of seeing itself. Even his less-than-perfect films, in which too much is spoken and too much resolved, there are sequences or shots of formal inquisitiveness that concentrate the attention and reveal a filmmaker who, although his interest is less than thoroughly engaged, can formulate a cinematic idea and calculate it to a small perfection. Hitchcock is one of the few commercially successful filmmakers who give the viewer pleasure by means of his formal deliberations. For popular cinema—a form of expression dedicated to hiding its formal structures—this is a major achievement.

But there is an unsettling anomaly at work here. The elegance of Hitchcock's formal structures and the pleasure we take in watching them in operation belie the content they generate: images and narratives of violence and disruption; attacks on complacency and routine; sexual cruelty and a disturbing misogyny are created in visual and narrative fields whose eloquence and intelligence seem to transcend their content. Something of a sadomasochistic pattern is put into operation. We reverberate to the shocks endured by Hitchcock's characters and take a peculiar pleasure in the way they are perceived and the way in which we perceive them. We delight in the cunning with which the director represents this violence and respond favorably to the eloquence of the moral ambiguities that result in our pleasurable assent to violence and madness. When we see culpability and evil

portrayed as the twins of innocence and rectitude, we accept this contradiction with an almost smug knowingness. The pain of the revelation of moral complexity and uncertainty (which repels us in, for example, the political sphere) is accepted in the aesthetic as the insight of a clever interpreter of modernity. The calculation of it all, the almost obsessive construction of narrative, the composition and cutting of shots that force us to respond in predetermined ways to seemingly uncontrolled or uncontrollable acts, Hitchcock's complete command of our perceptions, turns upon reception into delight. We find pleasure in his authority and enlightenment in his calculations. Hitchcock and his audience are able to have it all ways: plot, character, suspense, fear, pleasure; a formal structure never invisible, yet intrusive only when one desires it to be; a structure of moral ambiguity lurking below the level of immediate cognition, all firmly buttressing the pleasure of narration.

Hitchcock calculated himself as part of the overall structure of his work. He foregrounded his presence by appearing in his films; he developed an instantly recognizable persona on television; and he entered the popular imagination with a distinctiveness unrivaled by any other filmmaker in fifties and early sixties American culture. This success on all levels created the event of the director as celebrity. His films were known; and he (or rather the public persona he created) was known through the work of film reviewers, who referred to almost any film that used suspense, shock, or a "surprise ending," as "Hitchcockian." His work was conflated into an adjective and misappropriated as a genre. It's not surprising that, with all this, Hitchcock became a very special example to the generation of film students turned filmmakers in the late sixties and early seventies.[1]

This is a special group of writers and directors, which now dominates American filmmaking. While not all were students in the literal sense (a few of them, like Martin Scorsese, did take degrees in film school, while others may have attended briefly or not at all), they were a generation who learned about film by watching movies on television and in repertory movie houses. Unlike their Hollywood predecessors, who learned filmmaking as a trade, coming up the studio ranks, many of the young filmmakers of the late sixties and early seventies saw film as a form of expression: subjective and malleable. One manifestation of that expression, one way of impressing subjective response and a love of the cinematic medium was by alluding to and quoting from other films. Hitchcock and John Ford were the touchstones for these new directors, and the films—The Searchers (1956) and Psycho (1960) in particular—the foundation for much of their work.[2]

The phenomenon of allusion, quotation, and imitation in film is complex. We need to divide some of the strands of these activities to understand what the new filmmakers were about and how Hitchcock plays a role in their work. The business of filmmaking has always thrived on the fact

that viewers remember films, stories, stars, and genres. The repetitions and sequels and cycles that Hollywood needs in order to reproduce narratives in large numbers depended—and depends still—on the viewer's ability to recall, respond to, and favor particular films. There is a discrete contradiction operating here. The classic American style of moviemaking and reception depends upon transparency and a kind of virgin birth. Every film emerges whole and new, actively suppressing its technical, stylistic, or historical origins. Yet audiences are depended upon to recognize similarities and repetitions from film to film, and indeed they must do this. If they did not, they would have no desire to see stars, plots, generic elements, narrative patterns repeated; and without that desire to fulfill, Hollywood filmmaking could not exist.

The post-fifties, post-French New Wave generation of American filmmakers exploited the contradictions. They too looked to repetition and depended upon audience recognition, yet did not care to make their work completely transparent. They did not want to hide the genesis of their films or suppress the fact that films come not from life or from an abstract convention of "reality" but from other films. Their films recalled not only broad generic paradigms or the sexual attractions of certain players but specific images, the narrative structure of individual films, the visual and storytelling stratagems of particular filmmakers. They interrogated that aspect of filmmaking that combines commercial necessity (repetition and imitation) with the work of the imagination (allusion and quotation) in order to provoke the audience into recognizing film history, and in doing so pleased the viewer by asking for her response and her knowledge. The cinema of allusion is made out of a desire to link filmmaker and viewer with cinema's past and inscribe the markings of an individual style by recalling the style of an admired predecessor. At its worst, it is an act of showing off; at its best, a subtle means of giving depth to a film, broadening its base, adding resonance to its narrative and a sense of play, and, through all of this, increasing narrative pleasure.

Various filmmakers refer to and incorporate other films in various ways, as John Biguenet demonstrates in his essay elsewhere in this book. Among the most interesting are the subtle allusive acts that operate on the level of pure form. In these instances, allusion is not quite the appropriate term, for here filmmakers are working with and advancing basic visual experiments tried out by their predecessors. Hitchcock is a particularly apt example, because he was constantly playing with formal devices, looking for ways in which elements of composition, cutting, and camera movement could be employed to express a state of mind or clarify perception, to bring the viewer into the progression of the narrative or hold her at arms length.

When Spielberg uses a formal Hitchcockian device in Jaws (1975), combining a tracking shot with a zoom, each moving in opposite directions, to

communicate a tense moment of perception and recognition, the result is powerful and terrifying. Hitchcock had experimented with the technique in Vertigo (1958) to indicate Scottie's fear and loss of control as he hangs from a roof or races up the steps of the mission steeple. He used it as a point-of-view shot, expressing his character's terrified perception of his situation. Spielberg expands its use to express not only the character's but the audience's response: it becomes the viewer's point of view as the sheriff, Brody, thinks he sees the shark in the water, while character and background simultaneously shrink from and expand into each other. Toward the end of Goodfellas (1991: a film of great, imaginative "tryings out" and experiments), Martin Scorsese refines the device even further. In a diner, Jimmy and Henry sit by a window, talking. The camera tracks very slowly toward them, while the scene outside the window zooms in at a faster speed in the opposite direction. The sequence impresses the characters' dislocation and prepares for the major turn in the narrative, when Henry betrays his gangster friends.

Such examples carry allusion beyond the point of play, inside joke, or plot device into the very system of visual narrative structure. They demonstrate that filmmakers work like artists in any other media: they learn from, copy from, and expand upon the work of their predecessors, exploring and exploiting their own tradition. The degree of success that each attains, however, is not equal. Brian De Palma, for example, has done the simplest arithmetic exercises based upon the Hitchcock equations. He alludes to Hitchcock's plot structures and plays with visual and editorial devices. Unquestionably, the majority of American filmmakers who attempt to recalculate the Hitchcock formula wind up diminishing the work of their subject. Rather than recreate or rethink the moral structures of the Hitchcock mise-en-scène, they simply exploit it, sometimes very quietly, as if out of desperation. Paul Verhoeven's and Joe Eszterhas's Basic Instinct (1992) is an example of an exploitation film in which sexual violence is made a metaphor for moral bankruptcy. But the metaphor is rendered useless because the film depends on its ability to sexually arouse its audience to assure its commercial success. The film enacts what it seems to condemn, leaving no space for introspection or comprehension of the viewer's own complicity in the film's narrative affairs. Despite the fact that Eszterhas keeps reaching into two of Hitchcock's most disturbing and questioning films about sexuality, Vertigo and Marnie (1964), he allows no space for speculation, only manipulation. A central premise of Vertigo , that male sexual obsession can be carried to the point of destroying both the subject and object of the obsession, is reduced in Basic Instinct to various sets of exclusive sexual provocations, in which a man and two women maneuver one another into sexual thralldom (a mainstay of popular romantic literature and middle-brow, commercial soft-core pornographic film), with the threat of death hanging

over every encounter. From Marnie comes the figure of the sexually tormented woman, psychologically broken into multiple characters, yielding, destructive, finally psychotic, and, in a ploy Hitchcock would never indulge, murderous.

Hitchcock's misogyny is well documented. But despite the suspicion and distrust of women manifested in much of his work, there is almost always an understanding that women, when they are figures pursued and possessed by men, are fantasies made up by men. They are (as Tania Modleski points out in The Women Who Knew Too Much ) fictions that belie innate personality and female desire, fictions that subordinate the female to the neurotic, often psychotic, male gaze. Notorious (1946) and Vertigo play upon this transformation, the latter film elevating it to a semblance of tragedy. Marnie examines the phenomenon in almost clinical fashion, as a woman, honest about her neurotic dysfunction, is reduced and finally raped by a man who believes he can transform her.

Eszterhas and Verhoeven do not care for abstractions or meditations on transformation. The central figures of Basic Instinct are present only to exploit and use one another, and the audience most of all. Hitchcock's troubled and abused woman is here turned into a sexual destroyer, and none of the shots of the Michael Douglas character driving along the California coast carry the weight of existential fear and sexual anxiety borne by Jimmy Stewart's Scottie as he pursues his phantom of desire through the streets of San Francisco. Basic Instinct is an example of the exhaustion of allusion and the employment of Hitchcockian technique as an act of exploitation and despair. To do Hitchcock may convince a filmmaker or his producer that he may be like Hitchcock, and with such similarity may come respect and admiration and ticket sales. But in the end, very few directors—perhaps only Martin Scorsese in America and Claude Chabrol in France—understand that recalculating Hitchcock means understanding the mathematics of the original formula, thinking the way Hitchcock thought, and reformulating the original so that the results not only allude to but reinterpret it. Again, it is a matter of comprehending Hitchcock's mise-en-scène: the spatial articulation of his films, which includes the way his characters are situated and the way they look at each other and are looked at by the camera. It is the mise-en-scène itself that gives voice to ambiguities of sexuality and the violence of the everyday, the subjects that most engaged Hitchcock in his best work.

Scorsese has made two films that actively engage Hitchcock. Taxi Driver (1976) reformulates Psycho (while it simultaneously situates its narrative pattern in The Searchers ). Within the figures, gestures, and ideological and cultural practice of the late seventies, Scorsese finds analogues for the return of the repressed, which Hitchcock represented in the late fifties. Taxi Driver incorporates dread, angst, and threat in the figure of Travis Bickle,

whose world is as tentative and malperceived as was Norman Bates's in Psycho. Cape Fear (1991), certainly a less complex and resonant film than Taxi Driver, uses Hitchcock in more devious ways than its predecessor. Rather than elide and reconstruct the methods of one film within another (as Taxi Driver does with Psycho, embracing as much as remaking it), Cape Fear uses Hitchcockian technique to solve some problems. Just as Hitchcock used the perceptual structures of film to solve thematic puzzles and simultaneously engage and distance his audience, Scorsese turns to Hitchcock to solve other kinds of problems and provide a kind of secret narrative structure for a film that even its director admits is a minor, unashamedly commercial work. Within this "secret narrative" lie some of the most interesting reformulations of Hitchcock, unobtrusively, and with a great deal of humor and play.

When Cape Fear was being edited late in the spring of 1991, Scorsese gave a talk about the filmmaker Michael Powell at the Library of Congress as part of a program celebrating British cinema. He made a number of interesting revelations. One concerned the extent to which his own imagination was nurtured by cinema, and the fact that the choices he made and the problems he solved in creating his films depended in excruciating detail upon other films. He said, for example, that the close-up of De Niro's eyes during Taxi Driver 's credit sequence was suggested to him by a similar shot of the eyes of a gondola oarsman in Michael Powell's little-known film, Tales of Hoffman (1951). This is more than allusion or the simple celebration of cinematic community. It is, rather, the activity of a profound, subjective intertextual imagination that links Scorsese with the modernist writers of the teens and twenties and with the cinemodernists like Godard in the sixties, who looked to the writers and filmmakers who proceeded them as the usable past that must inform their own work. For the modernist, a "new" text is built from the appropriation and accretion of other texts. In a basic, material way, modernism demands that the works of imagination remain viable and usable, that they exist as the seeds of other works. Through such incremental nurturing a history of the imagination is written.

At its very best, the modernist act of allusion reveals form and structure through dialectical play. A new work, coherent in its own structure, gains that coherence by absorbing and restructuring other works. A kind of imaginative space is marked out that is open to other spaces and in that openness is made secure. "These fragments I have shored against my ruins," T. S. Eliot writes—or rather quotes—in The Waste Land . This is intertextuality as imaginative redemption; and that is precisely what is going on in Cape Fear, a secret remake, knowledge of which reveals the film as joke and intricate reformulation, a way of knowing Hitchcock and absolving Scorsese.

At his Library of Congress talk, Scorsese made an admission of sorts. In return for the financial and moral support given The Last Temptation of Christ

(1988), he owed Universal Pictures six films. Cape Fear was the first of these, and it was consciously and eagerly made quickly, cheaply, and with an eye on the box office. As an indulgence in the thriller-horror genre, and drawing upon a multitude of sources, it was aimed to please its audience and its creator. Part of that pleasure was in the remaking of an earlier film of the same title and basic plot structure, J. Lee Thompson's 1962 Cape Fear (a Universal property). Were it only a remake of this earlier film, it would be a somewhat interesting aside in Scorsese's career, a successful attempt at a commercial film (as big a moneymaker as Scorsese has had and an even better film than an earlier commercial attempt, The Color of Money, 1986, which was itself not a remake, but an extension of yet another film, The Hustler, 1961). But it is apparent that Scorsese calculated to produce something more than a quickie remake. He would, in effect, create a number of remakes in one: within the remake of the 1962 Cape Fear would be embedded a kind of remake of three minor Hitchcock films from the early fifties: Stage Fright (1950), I Confess (1953), and Strangers on a Train (1951). In other words, having decided to do a minor film within his own canon, he turned to films in Hitchcock's canon in order to discover how a minor film could best be done: to try, in effect, to recreate a minor Hitchcock film. The result is still not anything more than a minor film; yet it is one that plays a game of intertextual counterpoint, a modernist exercise in popular form in which one film adopts the plot of its predecessor while gaining a deeper structure through an allusive tag game with three Hitchcock films. The result is enormous pleasure for the maker of the film and the viewer who perceives the games being played.

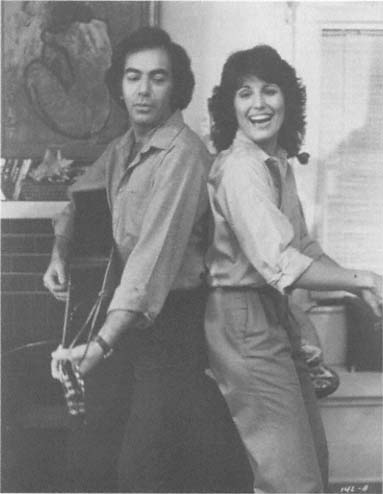

All this becomes even more interesting when we realize that Thompson's 1962 Cape Fear is itself a Hitchcockian exercise, a film that plays upon Psycho, or, more accurately, the atmosphere of Psycho and its reception. The production of Thompson's film is explicitly connected to Hitchcock. Bernard Herrmann, who wrote the score for Psycho (as he did for most of Hitchcock's fifties films), wrote the music for Thompson's Cape Fear . (Scorsese had Elmer Bernstein—an old hand at film music—reorchestrate a souped-up version of the same score for his film. He furthered the Psycho connection by having Saul Bass design credits somewhat similar to those he designed for Psycho .) George Tomasini, Hitchcock's regular editor, who cut Psycho, edited Thompson's film. Martin Balsam, who plays the detective Arbogast in Psycho, plays a police detective in Cape Fear . Gregory Peck, who had starred in Hitchcock's Spellbound (1945) and The Paradine Case (1948), plays Sam Bowden (Scorsese gives both Balsam and Peck small roles in his version of Cape Fear, as he does Robert Mitchum, the original Max Cady. (See figure 3.) There are visual references to Psycho in the 1962 Cape Fear, well before the time that allusions were to become prominent in American cinema: in the sequence where two detectives mount the steps in a boarding house

Figure 3.

Evoking Hitchcock through casting: Martin Balsam, Robert Mitchum,

and Gregory Peck in the original Cape Fear (1962) directed y J. Lee Thompson.

where Max Cady has brutalized a young woman, the camera tracks them up the stairs as it does Arbogast when he visits Norman's mother.

Thompson's film explores issues of violent sexuality, just becoming explicit in film as a result of Psycho . He examines "normal" middle-class people intruded upon by a psychotic, uncontrollable, and ultimately unknowable individual, and he observes an ordinary and plain middle-class landscape turned suddenly threatening by an amoral and dangerous presence. In short, Thompson attempts to recreate the mise-en-scène of Psycho: a gray, ugly world charged with violence and sadomasochistic sexuality, a world of ordinary people put in danger, a world of psychotic presences teasing and seducing middle-class morality and straining its oppressive limits. Psycho had come as a challenging and changing force onto the site of fifties American cinema, which, superficially, was as quiescent and predictable as the culture in which it was made. Few films outside of low-budget crime movies spoke to the political and moral despair of the period. To be sure, some of the decade's melodramas—notably those of Douglas Sirk and Nicholas Ray—suggested the fears and threats of domesticity on a social level above

that represented in the gangster film. But these works almost always indulged in an obligatory, if ironic, recuperation of at least one of the main characters in an attempt to negate the terrors of dissolution within the narrative. Hitchcock, in The Wrong Man (1956) and Vertigo, began a concerted effort to represent a world that was not recuperable, a world hostile to ordinary emotional life in which individuals were shown as helpless in face of uncontrollable events, incapable of normal responses, and destructive of themselves and others. Together, these films spoke the unspeakable in a decade devoted to amnesia and evasion. In Psycho , finally, the articulation of despair was stated with such violence that there was no longer a possibility of recuperation.

Psycho placed the grimness of The Wrong Man within the emotional abyss of Vertigo and out of the two created a physical and emotional landscape unrelievedly barren and violent. It did this with such force and self-consciousness, and such self-awareness, that it startled viewers not only with the blackness of its vision, but its humor, the unrelenting notion that some kind of joke was being played. Psycho, as its creator never tired of saying, was in fact a joke, a story that kept giving itself away in the process of its telling. But its playfulness made its seriousness all the more disturbing, and the force of its darkness penetrated American film and slowly changed it. Thompson's Cape Fear, coming less than two years after Psycho, was among the first to reproduce its fearsome insistence that the disruption of madness is a given in a world that counts on an illusory continuum of the ordinary.

But let's be clear. The 1962 Cape Fear has none of the complex resonance of Psycho . It does, in the character Max Cady, have its own version of Norman Bates, the madman who, from moment to moment, appears normal and self-contained (it is interesting to note that Scorsese, in his version of Cape Fear, is uninterested in this bit of Hitchcockian drollery: his Max Cady is a fearsome crazy man, a parody of recent unkillable movie monsters, a self-proclaimed "big bad wolf," a sadistic creep from beginning to end). It also has its middle-class family, a much more respectable family than Hitchcock's unpleasant petite bourgeoisie in Psycho, whose grim world is turned over by the madman's appearance. The origins of Thompson's family are the ordinary fifties domestic melodramas, not the grim hotel rooms and storefront offices of the inhabitants of Psycho . What the original Cape Fear takes from Psycho and exaggerates are its elements of sexual perversity and the inescapable attractions to evil, its bland black, white, and gray landscape that absorbs and gives back threat from the madman's indwelling. Here—though not as subtly as in Psycho —smugness and seduction, propriety and corruption work smoothly, implicitly together.

By 1991, few representations of sexuality and violence were still considered transgressive in cinema. The host of Psycho imitations during the intervening years had raised the ante of violence simulated and depicted to

appalling levels. In 1962, Thompson's Cady does the literally unspeakable and unseeable to the young woman he picks in a bar. The act goes on behind closed doors. Afterward, the woman will not even tell the police what Cady did, and she leaves town. In Scorsese's film, the young woman is sexually active and insecure, she was Bowden's lover, and Cady picks her up and brutalizes her not as a general threat to Bowden, but as a specific act of revenge. The act does not go on behind closed doors. We are privy to Cady's sadism: he breaks the woman's arm, bites a chunk out of her face, and spits it across the room. Scorsese, as is often his wont, throws representations of violence in our face because he likes to; because he knows a large part of the audience likes it; because (in his better films, at least) such images are among the articulate essentials of the world he is mediating and a vital component of the character is he is creating within this world. But something else is happening in his Cape Fear . Scorsese is attempting to refashion the moral landscape of the original film. His Sam Bowden is something of a pompous fraud who concealed evidence at Max Cady's trial (a morally correct but legally culpable act). Therefore, Cady's vicious actions come not from madness simply but from an insane sense of righteousness and revenge. Unlike his predecessor, he acts as Bowden's bad conscience; he is—and here Scorsese begins to get closer to Hitchcock—Bowden's double, his own corruption made flesh, the bleakest image of his own desires and destructiveness. Seduction and pain are not merely the ways Cady uses to get back at Bowden; they are ways of exposing the worst of Bowden to himself.

For Hitchcock, the creation of the double was a means of structuring moral ambiguity, which I noted earlier is so basic to his work. More than most filmmakers, he builds his mise-en-scène out of a counterpoint of gazes, of characters looking at each other and the viewer looking at the characters within spaces that contextualize those gazes as intrusive, threatening, and violent. The possibility of visualizing one character as a reflection of the other, or one act or gesture as a mirroring of the desire of the other, grows easily out of such structures. With looks and gestures, Hitchcock rhymes his doubles: Charlie and young Charlie are introduced with similar shots in Shadow of a Doubt (1943). Sam stands by his reflected image in the mirror as he attempts to face down Norman Bates in the motel office in Psycho . Judy-Madeleine in Vertigo is a double doubled: she is the fault line of Scottie's psychosis, his desire made impossible flesh. And in turn she is two women to him: one the person someone else created, who Scottie turned into the image of his beloved, the other the "real" woman he thinks is someone else and proceeds to recreate again into the image of his love. Often the doubling structure takes place in the exchange between image and viewer, the latter given an image of sadomasochistic desire through his or her assent to the characters' actions on screen and thereby becoming a kind of fantastic double of the character on the screen.

Each of the three fifties Hitchcock films that Scorsese draws on for his Cape Fear—Stage Fright, I Confess, and Strangers on a Train —is built on the concept of the double. Stage Fright is the most subdued of them. Were it not for the fact that it is so flat and arrhythmic, its performances so without energy, it could well be the most interesting, for it doubles and quadruples its doubles, setting up what should be an intricate structure in which many of the major characters play roles, making believe they are other than what they appear to be, and lie to themselves and the audience (the body of the narrative is told in a flashback that communicates false information), each reflecting the other's bad faith. Jane Wyman's Eve attempts to protect her boyfriend from the accusation of murder, one presumably committed by Marlene Dietrich's Charlotte Inwood (an aloof and potentially powerful character, who the film manages to humiliate and almost destroy in its rush to recuperate Eve). (Cf. Modleski, 115–17.) That the murder was committed by Jonathan, Eve's boyfriend, becomes fairly clear late in the film but is not fully revealed until a powerful sequence in which a clearly psychotic Jonathan admits his crime and his madness in the prop area of a theater. Scorsese draws this sequence, like a thread through the eye of a needle, into the high school episode of Cape Fear . In the 1962 version, Sam Bowden's daughter is pursued—or rather thinks she is pursued—by Cady in her school. Scorsese is uninterested in such simple images of pursuit and more concerned with the inexplicable sexual seductiveness of Cady and the effect of that seductiveness on Bowden's daughter. Echoing the penultimate sequence in Stage Fright, he places the man and woman in a stage set (here an expressionist image of a cottage on the stage of a high school auditorium) where Cady awakens the sexuality of Danielle Bowden and puts her under his control.