The Private House As a Barometer of Change

In the first years of the period 1966–85, few juries were interested in private houses. Then, in the 1967 PA awards, postmodernism made a strong appearance in Robert Venturi's "architecture of allusion" and in the presence of Charles Moore, another leader of the movement, among the judges. Musing over Venturi and Rauch's four submissions, the planner

David Crane summed up (with unwarranted optimism) this jury's ecumenicism: "I am interested in the fact that in the next twenty years we are going to build as many cities as we have already built. Someone like Venturi is not interested in that; he is interested in individual, particular, special things. But I agree . . . that architecture really is bigger than either my architecture or Venturi's; it's a more inclusive thing ."[28] The inclusive line thus reconciled the design of single architectural objects with that of whole environments. In 1968, the judges' twelve awards (among which were one house, a church, a chapel, and a high school addition) appeared to continue the same line. And yet, though much had happened between the lines in 1968, the judges contradicted the professional diversity recognized by the awards by their unanimous endorsement of large-scale projects as architecturally superior.

Lawrence Anderson, dean of Architecture and Planning at M.I.T., identified large projects with progress. Since the future of materials development resided in industrialized construction, the individual house was not important to him, "not on the technical end, anyway." For the planner Richard Dober, "a multi-client aspect" explained the higher quality of large-scale work, and SOM's engineer Fazlur Kahn, the brilliant designer of the type of structure that supported the tallest buildings in the world, concurred: "The large projects seem almost always to be more rational . . . . One of the reasons . . . is because large projects involve more people and bring in other disciplines as a total team." The architect Gunnar Birkerts, known for his industrial, corporate, and institutional practice, underlined that the new and challenging problems posed by large-scale projects were "really purifying for our profession." Finally, Romualdo Giurgola, the noted architect and educator who had come from Rome to study with Louis Kahn, began by observing that the issue was not size but meeting "the real needs of today," yet he immediately corrected himself. Because architects could not take large design projects as "a personal exercise," the greater discipline required by these projects made them architecturally superior: "A more genuine architectural language has always been set by projects of a comprehensive nature that have influenced the character of smaller ones."[29]

The 1968 jury had many large institutional projects and two remarkably innovative experiments in low-cost housing from which to choose. Their bias, which can easily be stretched to include corporate modernism, appears not in the nature of the awards but in the slippage in the emphasis of architectural meaning: from socially responsible large projects to the virtues of large scale per se. This slippage associates design discipline with

"multiclient" and "multispecialist" teams, emphasizing both technical innovations that require economies of scale and aesthetics that can be generalized across building sizes. Conversely, the small-scale projects are denounced—in Birkerts' words, for extreme "form-consciousness" that leads to the fashionable monotony of sloped roofs and diagonal lines. "The older guys [meaning more established architects] did not go for it, because they have a chance to play around with the real stuff, and big things too."[30]

The attribution of intrinsic superiority to large-scale work reproduces the notions of architectural significance reflected in the established professional hierarchy and in accepted career patterns. The 1968 judges did insist that the individual house should be a "laboratory for experimentation," but this seems no more than a cliché, belied by the notion that large-scale work (and, indirectly, the program) is the primary generator of innovation. In successive years, as the PA editors begin to include the revisionist representatives of small "idea firms," the inclusion of what might be called "boutique architecture" becomes less of a token gesture.

In 1970, two architects of equivalent though antithetical fame—Robert Venturi and Bruce Graham of SOM-Chicago, the architect of the Hancock and Sears skyscrapers—pick up the issue of the single-family house. Venturi places it neatly on the artisan side of architectural practice:

On one level, this kind of house is insignificant and is not responding to the social crisis. But in a funny kind of way you solve problems by indirect routes, and who can say that the little house for the rich man is not one of them. Architects don't get many research grants as yet and especially for a young man who is lucky enough to have a rich uncle, it's a fine opportunity for experimenting. . . . I think the architect is essentially a craftsman who can do what the society allows him to do . . . . Thank goodness there's an opportunity for the young architect who does not want to go immediately into an organization to do his individualistic thing!

Graham's response mixes and displaces meanings from the two metaphorical sets:

You could use [a house] as an experiment with the technical tools. For instance, if someone has designed an expensive prefabricated house, it would be very relevant. It also gives you the opportunity to create new spaces, a kind of poetry, an experiment with a new way of life. A lot of people resent this since it implies that their present way of living isn't so good. . . . I am not really interested in anyone's love affairs, therefore I'm not interested in a house that becomes too personal—then it's not really for others to discuss. I think it has always been true that great houses have had social impact . . . . Breuer's early houses . . . were all related to one another so that they became a sequential group of art forms, and for this reason . . . they were very important.[31]

Starting with technology (as a good modernist should), Graham moves quickly to embrace its "opposite," architecture as art. Endowing art with the capacity to change life, as did the European modernists, he nods in passing to the criticism of architects who impose their own preferences on the users. Then, in a sarcastic tone, he opposes the personal dimension of a small-scale design and the collective responsibility of architecture. But he refers to the architect's social role only to confuse it, as he equates "social impact" with great art in a specific reference to the Bauhaus architect Marcel Breuer.

This is still an ambiguous and reluctant endorsement of the designer's ability to transcend even inconsequential programs. Art transcends service if it acquires a direct social function. The ambiguity disappears in later juries with the affirmation of the tendency that Richard Pommer has aptly called "architectural supremacism."[32]

"Supremacism" appears in Peter Eisenman's 1975 pronouncement that the architectural potential of the house lies precisely in the fact that its program is well known, conventional, and insignificant: "Most other types of buildings differ from houses precisely because the functions are so explicit; consequently they have no room for any kind of statement about iconography, meaning or intention; the ideas are subsumed in the program."[33] Eisenman's tribute to the house relies on the building's potential as a metaphor for the architect's ideal role but reverses the positive values, from social responsibility and service to self-expression and art. Yet the preeminence of design over program is an ideological position that corresponds to specific conditions of practice. Supremacism is therefore still addressing, even if silently, the antinomies of practice evoked by the first house metaphor.

This was 1975, two years into the worst recession since the end of World War II. The New York Five had just been created by the Museum of Modern Art and the press. Peter Eisenman had been at the helm of New York's Institute for Architecture and Urban Affairs since 1967. His architectural record consisted of unbuilt projects and a few houses, as did that of Michael Graves, Eisenman's former colleague at Princeton and fellow member of the New York Five. Seven years later, during the shorter recession of 1981–83, Graves had won the Portland and Humana competitions and left small-scale work behind. Nevertheless, in the PA jury of 1982 he still traced a mixed connection, romantic and realistic, between design talent, the private house, and the architect's practice.

In that jury, the planner and feminist historian Dolores Hayden complained about the award conferred to Ralph Lerner, a young man on the

Princeton faculty: "This mountain-top palace for a Brazilian tycoon seems to come out of the far distant past, when one thinks about architecture as a service for the very rich and the very remote." Graves rushed to his colleague's defense: "I would be quite delighted to have this architect design a city hall or a children's home or almost any other kind of project involving the public at large because of the incredible sensitivity to . . . [our] size and proportion . . . as we occupy the rooms . . . [and] as we identify collectively."[34] While Graves sees talent as an inalienable asset that the individual transfers from project to project, the hidden reference to the constraints of practice is unmistakable: Young architects demonstrate their talent in whatever way they can. Viewing residential commissions with favor and asserting the primacy of design thus merge in defense of the potential of architects who do small-scale work.

In fact, the ideological "art" element present in both semantic sets is what joins the individualistic, artistic side of the house as metaphor for the architect's social role to the "artisan" side of the house as metaphor for architectural practice. This joining, however, is not only ideological: it involves a realistic assessment of the work available to architects—young and not so young—in hard times. Recessions, we could fairly say, make realism compulsory.

In 1976, one year after Eisenman's proclamation of design, the entries were reduced to an all-time low of 462; nothing seemed to deserve a First Award for architectural design, but four out of ten citations went to private houses. The architect Arthur Cotton Moore voiced the jury's regret that good multifamily housing projects and planned developments had been as absent as good commercial buildings: "The major thing that's going to happen in cities is commercial and speculative investment development [a prescient statement, as we know]. . . . The few submissions we had were inept, obviously indicating that the architects had no actual power or causal role in these things . They were absolutely just fluff. . . . In the end we have to fight like demons to keep from picking all single-family houses."[35] Raquel Ramati, juror for planning and urban design, noted that even in the very competent plans she had seen, the architect's influence was missing. Nor were architects involved "in the design of suburbia or of mobile homes, where most people really are affected." Stating the obvious, she confirmed Moore's interpretation: Architects' concentration on the house was a strategic but forced retreat "into an ever smaller realm where [they] can operate."[36]

To conclude this point: The revisionists' reappraisal of the single-family house proceeds from an ideological view of "pure" design that reflects the

practice of architects with nothing better (or bigger) than single-family houses to do.

Concurrently with the rise of "architectural supremacism," a complex revaluation of the house was emerging from the critique of large urban complexes and from the preservation movement. The preservation movement's historical beginning may be traced in the accounts of the East Coast architects I interviewed. John Morris Dixon remembers "about 1960 marching to save Penn Station," the grandiose 1910 building by McKim Mead and White, replaced by the drab anonymity of Madison Square Garden Center at the end of the 1960s. The preservation movement, Dixon believes, reversed more than a decade of academically induced, doctrinaire contempt for historic architecture:

I think our generation [he graduated from M.I.T. in 1955] had a kind of aversion to recognizing the value of historical structures. . . . But as soon as these things began to happen, you had to think of what it was about these buildings that made them worth preserving. I had had very little exposure . . . only one course, in my senior year, at M.I.T. Seeing them as I did, working on the AIA Guide for New York, I began to learn to identify and distinguish historic styles.

Preservation and contextualism compose what I call a principle of "environmental nondisturbance." In a blanket reaction to modernist urban renewal, it induces a revaluation of the house as a potential art object, not despite its program but for its nonobtrusive program. Let us examine the steps involved in this reassessment.

Disdain for the single-family house is a logical complement of the "large-scale bias" that transforms the undeniable public impact of large projects into a significant public good. This bias is aligned on the public, collective side of the house metaphor, bespeaking the architects' ambition to play a significant social role. But significance is a contested notion, as is the role of architects in large urban complexes that rarely satisfy the users' conception of what is good. The ambition to have a positive effect on collective welfare reflects long-standing utopian aspirations. But the exclusion of the users from the planning and design of public projects almost inevitably gives a technocratic slant to professional ambitions. In contrast, the single-family house can be revalued as an antidote to the invasive and technocratic implications of large buildings. Both the preservation movement and the emphasis on craftmanship are pivotal in this new set of attitudes toward the urban house.

Preservation appeared in the 1960s as a middle and upper-middle class response to the destructive invasion of cities by urban renewal. The juries' taste for different architectural vocabularies shifted various ways during

the period under study. Yet preservation and reuse became the focus of a movement that outlasted, for instance, the concern with energy-saving design following the 1973 oil crisis. The PA awards began to reflect this crucial change of attitudes in 1969. The award given to James Polshek for the headquarters of the New York State Bar Association—three old townhouses renovated and connected by a multilevel terrace to a new building in back—was hailed by Roger Montgomery "as possibly the most portentous of all the projects that we finally selected," a sign of modern architects' "coming of age . . . in terms of their leadership of responsible preservation efforts."[37]

Preservation obviously influenced the architecture of historicist and vernacular allusion that architects call "postmodernism," although architects express regard for the past in different ways. One way is image, which emphasizes fitting single buildings into their environments by choosing appropriate proportions, vocabulary, and ornament for their facades. Urban contextualism preserves the preexistent architectural order by "writing in" new components, as it were, in a compatible design language.[38]

Contextual and sympathetic design applies to all building types, but the house comes in through the preservation movement's essential concern with program—more exactly, with making preservation and reuse a premise of all new programs. Thus, with its simple, conventional, and flexible program, the relatively nonintrusive town house becomes a favorite object of the urban "nondisturbance principle." At the same time, its constructional complexity redirects the designer's attention from formal innovation to craftsmanship, another facet of the house as metaphor for antitechnocratic architecture.

The potential for successful collaboration between architects and users is more likely to be realized in a small and manageable project, especially one as dear to its occupants as the private home, than in any other kind. Thus, as the metaphor for practice, the house may come to represent a "publicness" more subtle than what either large size or collective ownership imply: In the process of applying expert knowledge, diminishing the distance between the professional and the layperson is a way of opening the process and increasing the client's access to knowledge. However, gentrification and other types of residential reuse in cities most often limit the reduction of distance to relatively affluent clients. The antitechnocratic potential thus remains circumscribed within the relations of good craftsmanship.

The craftsman does not look to change the canon of his or her métier but to produce a lasting object, adequate to its functions, its circumstances,

and its users. In architecture, attention to the program predisposes the craftsman to respect the environmental considerations imposed by the site. Although the concentration on doing a task well for its own sake can apply to all projects, it is compromised by the complex division of labor (and by industrialized construction) in the largest ones. Small scale makes it possible for the professional to practice architecture as service, design, and construction.

A craftsman tends to respect traditional type-forms—conventional cultural notions of what an office building, a factory, a school, a church are supposed to look like. Despite its merits, this respect for type-forms appears conventional by contrast with loftier architectural aspirations. Craftsmanship and propriety tend to be prime criteria of evaluation when the juries, having withdrawn from technocratic ambitions, also become critical of an abstracted notion of "Art." In a period of paradigmatic demise, these criteria are insufficient to reconstruct a consensus.

The conflict of standards was strikingly illustrated in 1978, when the presence of Natalie de Blois on the jury subtly infused gender into the debate. She resisted giving a First Award to a large suburban residence and was outvoted by Charles Moore, Richard Meier (the most prominent of the New York Five, known for uncompromising aesthetic purism and allegiance to Le Corbusier), and Edward Bain, partner in a first-rank Seattle firm. The implicit ideal of a well-crafted, adequate solution runs through her objections to equating overdesign with art:

Richard likes it because of the form, I dislike it because of the form. The forms and the spaces inside are so confused, the whole thing is so arbitrary that the resulting spaces are small and cramped. . . . It is tedious to approach the building on the long walkway. There is no service entrance for the kitchen, for bringing in groceries, removing garbage. . . . An enormous amount of space is used for circulation . . . [and given] to closets, to toilets. There has been an awful lot of effort to create a jungle gym on the outside.

Charles Moore's rebuttal is remarkable: "Given the incredible and altogether gratuitous task that he has taken on, . . . [he] does manage to bring it off with power, verve and a sense of danger." He responds to a casual question by de Blois that such a house could not have been designed by a woman: "It has a kind of aggression that one has associated with males. With all my strong reservations about it and my sense that it is just on the verge of collapse and chaos, I'm strongly attracted to it and I want to give it some really fancy prize."[39] While the three men took the large family house as "the appropriate setting for an experimentation process," it is difficult to imagine a woman endorsing power, a sense of danger, and male

aggression in a house . Craftsmanship informs de Blois's sense that a house should serve the client's purpose with propriety and within conventions, the opposite of an "incredible and gratuitous" task. It also restrains her from encouraging originality.

The house, as building type and metaphor, has held program constant, letting the emphasis on design per se fluctuate according to the jury's position. The contending positions are now in place, but they are not permanent: modernist dogmatism is definitely on the wane. Yet there is not one clear successor. For this reason, eclecticism must be tolerated. The architectural supremacists' emphasis on design admits historicism for single buildings and contextual "blending in" as much as daring, idiosyncratic, theoretical new departures from modernist abstract geometries. While the concern with preservation and "nondisturbance" nourish both historicism and a return to the craft of building, the connection with art and theoretical developments remains more closely wedded to audacious formal invention. On both counts, the notion of the architect's social and public role appears to be either suspended or drastically revised.

We may proceed now to analyze the chronological transformation of architectural discourse during the period 1966–85. This period encompasses two declines of construction during the 1960s, the severe recession of 1973–76, and Reagan's recession in 1981–83. At its center, there is a professional crisis. The juries' debates increasingly reveal the double toll taken by the economic recessions and the internal crisis of meaning. Architectural supremacism, which makes a clear entry into the jury's debates in 1975, is a turning point. I take the priority accorded to design as an attempt to find a symbolic resolution for the internal crisis. This ideological reordering cannot resolve (even symbolically) the real crisis of the profession, but it still becomes a principal axis of the postmodern transformation.

1.

Le Corbusier. Plan Voisin for the rebuilding of Paris. Model.

1925. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

2.

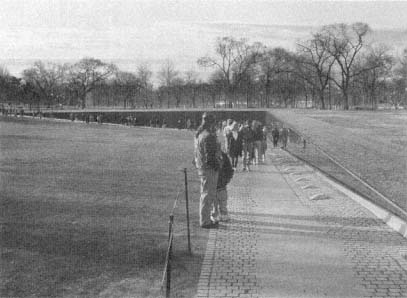

Maya Lin. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial,

Washington, D.C. 1982. Photo: Charles Larson.

3.

Walter Gropius. Apartments at Siemenstadt,

Berlin. 1929–31. Photo: Roland Schevsky.

4.

Bruno Taut. Hufheiser Siedlung, Britz, Berlin. 1925–31. Photo: Roland Schevsky.

5.

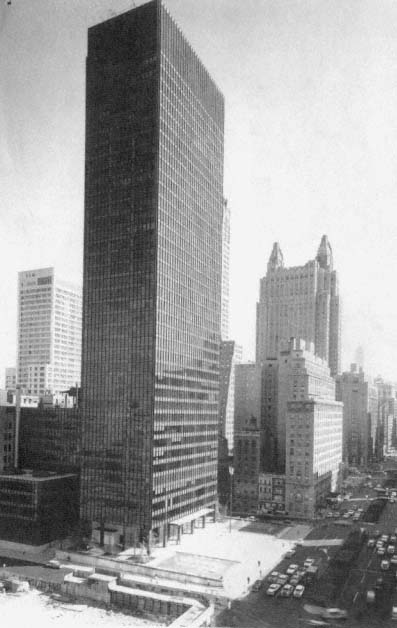

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe with Philip Johnson. Seagram building, New York.

1956–58. Photo: Ezra Stoller. Courtesy of Joseph E. Seagram and Sons, Inc.

6.

Philip Johnson John Burgee. AT&T World

Headquarters, New York. 1984. Photo: Richard Payne.

7.

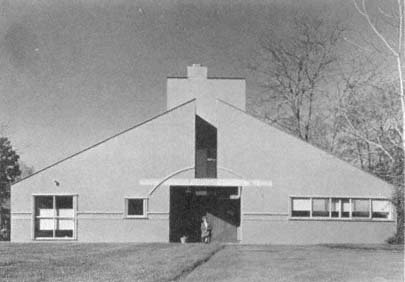

Venturi and Rauch. Vanna Venturi's house, Philadelphia. 1962. Photo:

Rollin la France. Courtesy of Venturi Scott Brown and Associates.

8.

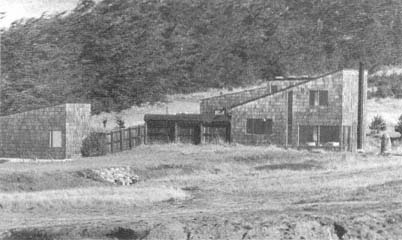

Joseph Esherick and Associates. Sea Ranch, Calif. 1965.

Photo: Peter Dodge. Courtesy of Esherick Homsey Dodge Davis.

9.

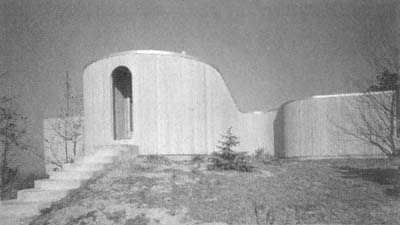

Stanley Tigerman. Daisy House, Porter, Ind. 1976–78.

Photo: Howard N. Kaplan. Courtesy of Tigerman McCurry.

10.

Robert A. M. Stern. Residence at Chilmark, Martha's Vineyard, Mass.

1983. Photo: Wayne Fuji. Courtesy of Robert A. M. Stern, Architects.

11.

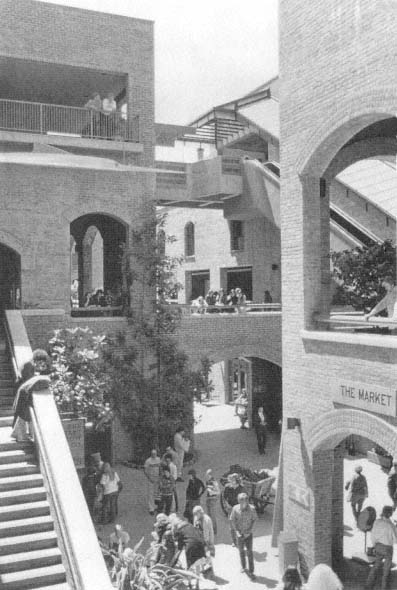

Esherick Homsey Dodge Davis. An early example of urban reuse: shops

at the Cannery, San Francisco. 1966. Courtesy of Esherick Homsey Dodge Davis.

12.

Cesar Pelli. Pacific Design Center, Los Angeles. 1971–75. Photo: author.

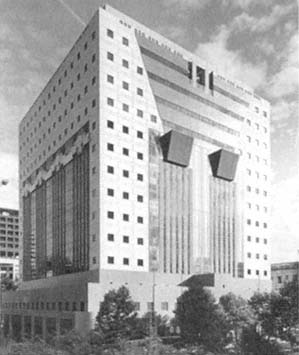

13.

Michael Graves. Municipal Services Building, Portland, Oreg. 1980.

Photo: Paschall/Taylor. Courtesy of Michael Graves, Architects.

14.

Kohn Pedersen Fox with Perkins Will. Procter and Gamble Headquarters,

Cincinnati. 1985. Photo: Jack Pottle/ESTO. Courtesy of Kohn Pedersen Fox.

15.

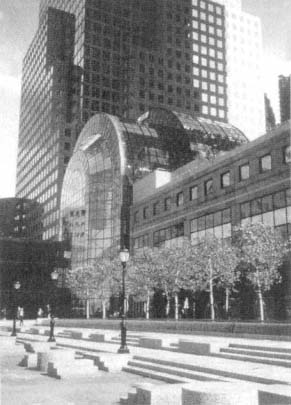

Cesar Pelli and Associates. World Financial Center, New

York. 1981–87. Photo: Cesar Pelli. Courtesy of Cesar Pelli

and Associates.

16.

Venturi Rauch Scott Brown. Gordon Wu Hall, Princeton

University. 1980. Courtesy of Venturi Scott Brown and Associates.

17.

Kohn Pedersen Fox. 333 Wacker Drive, Chicago. 1979–83.

Photo: Barbara Karant. Courtesy of Kohn Pedersen Fox.

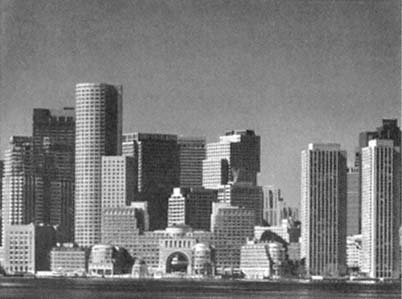

18.

Adrian Smith/SOM. Rowes Wharf, Boston. 1987–88. Photo © 1987

Nick Wheeler/Wheeler Photographics. Courtesy of SOM.

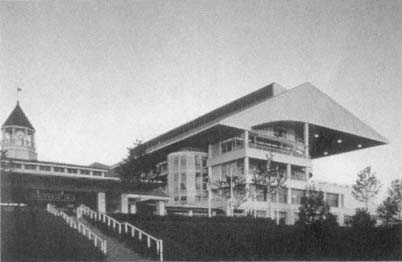

19.

Diane Legge/SOM. Race track. Arlington, Ill. 1989.

Photo: Hedrich-Blessing. Courtesy of SOM.

20.

Gwathmey Siegel. Taft residence, Cincinnati. 1977. Photo: Richard Payne.

Courtesy of Gwathmey Siegel and Associates and Richard Payne.

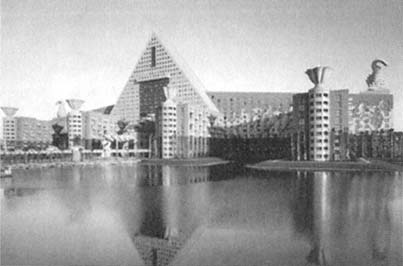

21.

Michael Graves with Alan Lapidus. Disney World Dolphin Hotel, Lake Buena

Vista, Fla. 1990. Photo: Steven Brooke. Courtesy of Michael Graves, Architects.

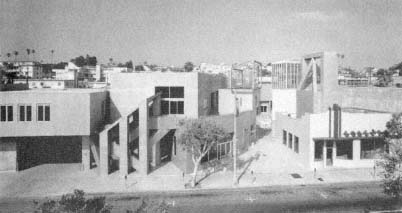

22.

Frank Gehry. Edgemar Center, Santa Monica, Calif, 1984–88. Photo: Tom Bonner.

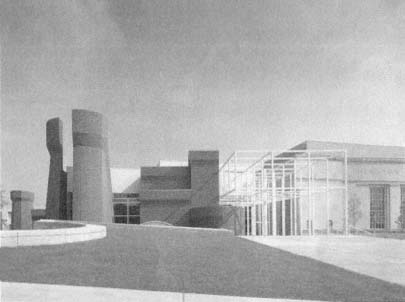

23.

Peter Eisenman with Richard Trott. Wexner Center for the Arts, Ohio

State University, Columbus. 1989. Photo © Jeff Goldberg/Esto.

24.

Joan Goody. Renovation of Harbor Point, Boston. 1989. Photo:

Anton Grassl. Courtesy of Goody Clancy and Associates.

25.

Koning, Eizenberg. Affordable housing, 5th Street, Santa Monica,

Calif. 1988. Photo: Grant Mudford. Courtesy of Koning Eizenberg.

26.

Rob Quigley. Baltic Inn, San Diego, Calif. 1987. Courtesy of Rob W. Quigley.