Rise and Fall of Opuntia, Australia

(Hosking and Deighton 1979; Mann 1970; Osmond and Monro 1981)

About 30 species of cacti native to various regions of North, Central, and South America have become naturalized at least locally in Australia. Nine of these have become pests over considerable areas of southeastern Queensland and northern New South Wales. Australian botanists generally identify the worst pest cacti as belonging to two species, Opuntia stricta and O. inermis . American botanists generally consider O. inermis to be a synonym of O. stricta . What is called O. inermis in Australia may be called O. dillenii in the Americas. Whatever they are called, these prickly pears are native to

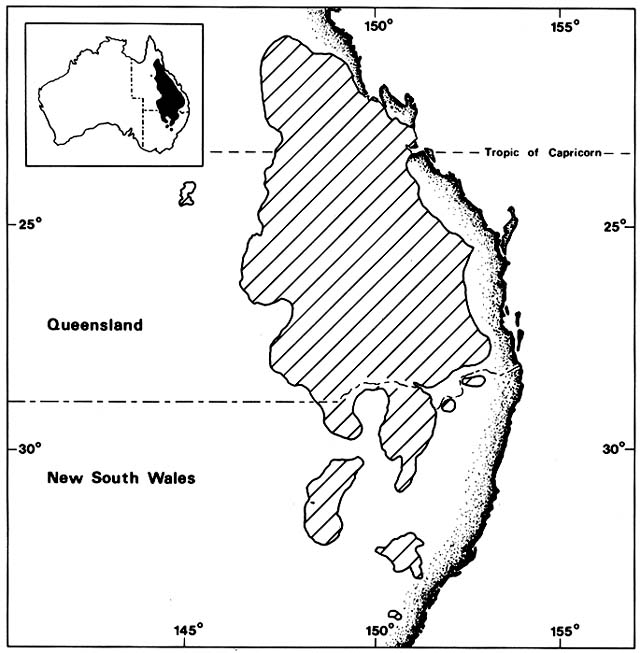

Figure 6. Maximum Range of Two Introduced Cacti (Opuntia stricta and O. inermis ) in Australia. Many plants

have become aggressive invaders when dispersed to regions free from their former parasites and herbivores.

Australia had no cacti until the nineteenth century when various New World species were introduced in cultivation.

Several of these escaped and spread rapidly in spite of control efforts. The map shows the combined ranges of the

two worst pest species in the early 1920s, before they were eliminated by insects introduced from South America.

(Adapted from Mann, 1970)

seashores of the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean. How and when they reached Australia is unknown, but by the mid-nineteenth century they were being widely planted for hedges by homesteaders in eastern Australia. Both spread on their own on the cattle and sheep ranges and were recognized as a nuisance by the 1880s. Dispersal was partly by vegetative propagation from pads adhering to livestock and partly by seed. The fruits were attractive to feral pigs, emus, and many other mammals and birds.

How successful the cacti would have been if the region had been ungrazed is uncertain. They spread mainly in open savanna woodlands, largely dominated by brigalow, Acacia harpophylla , and Casuarina spp., vegetation types in which grass fires were a normal part of the system. Hotter fires in ungrazed grass would presumably have been harder on the cacti than on the native plants. Although the two Opuntia species did naturalize in some coastal sites similar to their home habitats, their main infestations were inland, on both sides of the Great Dividing Range, up to elevations of about 800 m. The western limit was about 650 km from the coast. At their peak in the early 1920s, the two Opuntias infested about 25 million ha of land between 21° and 33°S latitude (fig. 6). Mechanical removal and chemical control cost more than the value of the land. Many sheep and cattle holdings were abandoned as useless.

In 1924, the Queensland government paid bounties for the slaughter of 335,000 emus and other birds blamed for spread of cactus seeds. The following year it was estimated that the cacti spread at an average rate of 100 ha/hr.

The tide was turned by biological control, an approach pioneered by Australian entomologists. Work had begun in 1912, when the Queensland government sent an expedition abroad to find cactus-feeding insects. They brought back a moth species native to Argentina, Cactoblastis cactorum , which unfortunately did not survive. They also imported cochineal bugs, Dactylopius spp., which were successfully reared, but work was suspended for the duration of World War I. In 1919, the Commonwealth Prickly Pear Board was set up. New expeditions to the Americas collected many kinds of cactus-feeding insects, including about 50 new to science. These were reared in quarantine and screened by starvation tests on economic plants. The first insects to be released were cochineal bugs, Dactylopius opuntiae , native to the southwestern United States. The bugs were successfully established on pest cacti in several Australian localities in 1921–1923; by 1924 patches of the cacti began to die. The government, enthusiastically helped by private initiative, spread the bugs along all the roads in the cactus-infested territory. The effect, however, was somewhat disappointing as cactus mortality was highly variable.

The catastrophic wiping out of the cacti was not accomplished by Dactylopius but by Cactoblastis cactorum . This moth was reimported from Argentina and finally released throughout the cactus-infested territory in 1926–1927. Moth eggs were supplied by the hundreds of millions free of charge

to landholders. The larvae fed on the cactus pads, riddling them with tunnels; most of the cacti promptly collapsed and died. By 1933, 90% of the Queensland cacti were gone. The crash of the cacti was followed by a crash of the insect population; then there was some cactus regeneration and resurgence of the insects. The cycles continued in constantly damping waves. At present, only a few cacti and their obligate parasites survive in scattered colonies, carrying on a stable hide and seek, host—predator relationship.

The story is not over. The tiger pear, Opuntia aurantiaca , native to Argentina and Uruguay, became a relatively minor pest in eastern Australia after 1911. It is currently spreading in east-central New South Wales in spite of large sums spent on attempted control. Cactoblastis larvae feed on the tiger pear, just as they do in their joint homeland, but they are not lethal to the cactus and do not stop its spread.