Seven

Demille's Exodus from Famous Players-Lasky: the Ten Commandments (1923)

Antimodernism as Historical Representation: the King James Version of the Bible as Spectacle

When Motion Picture Classic published stills from "The Drama of the Decalogue" during the filming of The Ten Commandments , it repeated the anecdote that DeMille drew his inspiration for the film from the results of a Los Angeles Times contest for an original story. An avalanche of mail poured in from fans eager to see a production with a religious theme. According to a souvenir program, "The contest revealed. . . that. . . the clean, sober minds of the vast majority of people are not interested in froth but in the virile, vital things of life, the epic ideas of all times." Descended from a distinguished playwright who had written in his diary that he learned Greek by studying the New Testament, DeMille did not need much prodding to mount a lavish production about the biblical past.[1] A close analysis of the acclaimed spectacle shows that it represents not only a summation of the director's career at Famous Players-Lasky but a preview of his achievement in the sound era. The Ten Commandments thus remains a Janus-faced production that simultaneously looks backward and forward in time. On the one hand, the biblical epic signifies a return to the antimodernist tradition of civic pageantry in its representation of a macrocosta and its nostalgia for the moral certitude and sense of community associated with small-town life.[2] On the other, the director's technical achievement with respect to use of color processes, special effects, and colossal set design attests to the reification of religious uplift as spectacle in a modern consumer culture.

A narrative divided into two parts, with separate casts enacting plots in different historical periods, The Ten Commandments appeared innovative but continued in the tradition of Victorian pictorialism. As industry discourse

on the film's production attests, the Biblical Prologue dramatizing the exodus from Egypt attracted considerably more attention than the Modern Story of the Jazz Age. After setting trends in both fashion and filmmaking in the early postwar years, DeMille reverted to a narrative strategy based on intertexts as established forms of middle-class culture. Apart from invoking the tradition of historical pageantry, which reached its apogee in the years immediately before the First World War, he relied upon audience familiarity with the King James Version of the Bible and cited chapter and verse in the art titles. The Biblical Prologue of The Ten Commandments thus served as an illustration of the Book of Exodus or the Second Book of Moses in the Old Testament. As such, it appealed to the cultural taste of the genteel classes who were acquainted with the definitive illustrations of the Bible by Gustave Doré, a celebrated artist whose work was published in France in 1865 and subsequently appeared in expensive, gilt-edged editions in Great Britain and the United States. Although this religious iconography was undoubtedly familiar to adherents of liberal Protestantism, which became increasingly secularized in the twentieth century, the rise of fundamentalism meant that the Bible was widely read among the lower-middle and native-born working classes as well.[3] As Motion Picture News acknowledged, the casting of the Biblical Prologue required "players of unusual ability as their performance will be carefully watched by millions to whom they are familiar through Biblical reading." The trade journal was obviously not referring to Catholics, who, unlike Protestants, did not emphasize biblical study as a religious practice and, moreover, had adopted the Douay-Rheims translation from St. Jerome's Vulgate as opposed to the King James Version.[4]

Apart from the Bible and Doré's illustrations, DeMille's representation of the exodus has to be considered with reference to yet another intertext, sensational news reports about the discovery of the tomb of King Tutankhamun in November 1922. American newspapers, especially the Chicago Daily News , participated in coverage of the excavation that involved the Metropolitan Museum of Art in a significant role. According to Thomas Hoving, the event was "one of the longest-lasting news stories in the history of journalism [and] would continue unabated almost daily and weekly for eight years." A significant component in the construction of an Orientalized Middle East as a site of the mysterious "Other," the discovery of the tomb influenced the exploitation strategy of The Ten. Commandments . A section in the souvenir program titled "Lost Arts of Egypt," for example, referred to Tutankhamun on the assumption that educated filmgoers were informed about an event touted as "the most sensational in Egyptology."[5] Yet unlike Joan the Woman , which offended Catholics and failed to appeal to a broad audience, The Ten Commandments drew crowds of moviegoers who were unfamiliar with genteel middle-class culture. The fundamentalist lower-middle and native-born working classes, especially in small towns and rural

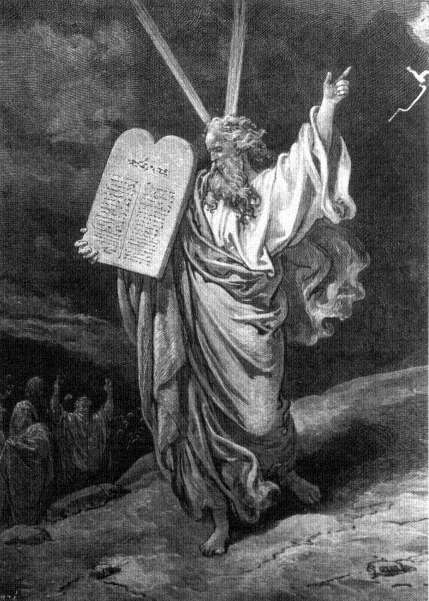

34. Gustave Doré's illustrations of the Bible, such as this one of

Moses, based on studies of antiquities in the Louvre, provided

DeMille with intertexts drawn from highbrow culture.

areas, most likely brought to the filmic text a belief in biblical literalism. As for uneducated spectators, the visual appropriation of unsurpassed spectacle in color was achieved without the mediation of such intertexts as The Doré Bible but within the context of both immigrant subcultures and a larger consumer culture. Addressing any possible objections regarding the religious content of the film that might offend a broad moviegoing public, Variety assured exhibitors, "It's a great picture for the Jews. It shows the Bible made them the Chosen People, and also (on the statement of a Catholic) it will be as well liked by the Catholics for its Catholicity."[6]

An aspect of consumption anticipated by historical pageants that were ironically organized to offset the lure of commercialized amusement, publicity about the building of Egyptian sets on sand dunes near the coastal city of Guadalupe, California, attests to film production itself as a form of spectacle and commodity fetishism.[7] A report in Motion Picture News echoed pre-World War I publicity in print media and newsreels about the expenditure of enormous resources to stage civic pageantry. Exhibitors read about the installation of a twenty-four-square-mile tent city to house 2,500 inhabitants and 3,000 animals, including horses, camels, burros, poultry, and dogs, assembled for scenes of the exodus. A complete utilities system providing water, electricity, and telephones had been built in addition to transportation facilities. Construction of the most impressive structure of the set, a massive entrance to the City of Rameses that measured 750 feet wide and 109 feet high, required 300 tons of plaster, 55,000 board feet of lumber, 25,000 pounds of nails, and 75 miles of cable and wiring. A fact sheet in the souvenir program repeated this preproduction publicity by stressing the extraordinary logistics involved in building the edifice and cited several statistics. After enormous cost overruns that nearly crippled Famous Players-Lasky, DeMille then buried the site in yet another spectacular act of consumption as waste and thereby recycled film history for future archaeological teams that recently excavated the sets.[8] Although not as sensational as the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb, the excavation of the filmmaker's version of the City of Rameses provided a strange reenactment of the study of antiquities.

Aside from the spectacle created by massive film production that paralleled the representation itself as a commodity form, DeMille's epic evinced other contradictions inherent in antimodernist civic pageantry. Perhaps most obvious was the construction of the Biblical Prologue as a succession of extreme long and long shots with cuts to occasional medium shots of the actors. As such, the epic represented a didactic series of tableaux for the edification of spectators that appeared stylistically regressive rather than producing the "eclipse of distance" characteristic of a more modernist aesthetic.[9] Yet the spectacular use of sets, crowd scenes, special effects, and color that dictated the scale of shots also elicited audience response tinged

35. Charles de Roche as the Pharaoh leaves the City of Rameses, guarded

by a massive gate, in the Biblical Prologue of The Ten Commandments

(1923). (Photo courtesy George Eastman House)

with sensation, excitement, and immediacy. For the entrance to the walled City of Rameses, for example, Paul Iribe designed a massive structure that, according to Motion Picture News , was the largest set ever constructed for a film. Forming a symmetrical design, the entryway to the city was flanked by a set of two colossal statues seated on a rectangular platform protruding from both the left and right sides of the wall. A set of monumental bas-relief of a horse-drawn chariot on the expanse of wall in turn flanked the twin sculptures of the pharaohs. Approaching this impressive facade was a wide, sweeping avenue lined on both sides with a row of gigantic sphinxes. In the distance, to the left of the massive gate, a pyramid pierced the sky of a limitless, arid landscape. Since DeMille adhered to a tradition of authenticity established by realistic stage melodrama and civic theater, the sets for the interior of the pharaoh's palace represented a curious departure at a time when news accounts stimulated interest in Egyptian artifacts. As opposed to the Doré illustrations based on antiquities in the Louvre, Iribe created a modernist representation with rectilinear Art Deco stairways for

the throne room and concentric pointed arches at the base of huge columns in a minimalist design dominated by the towering bust of a pharaoh.

Given that DeMille's representational strategy in the Biblical Prologue appears to regress to an era of antimodernist civic pageantry when audiences viewed spectacle from a distance, what accounts for the chorus of acclaim that greeted the film? A screening of a black and white print is extremely misleading because, as critics stressed, spectators were enthralled by the use of color in scenes of the exodus. Filmgoers who shopped in fashionable department stores had already become accustomed to eye-catching displays of colored lights and merchandise in plate glass windows during the 1910s. DeMille, who clearly influenced advertisers in their use of color after 1924, had previously experimented with color tinting and toning as well as the Handschiegl process with his cameraman, Alvin Wyckoff.[10] Apart from these techniques, the director used a new two-color Technicolor process that had been introduced, not coincidentally, in an Orientalist narrative titled The Toll of the Sea (1922) starring Anna May Wong. For reasons that are not entirely clear, DeMille broke with Wyckoff, who had photographed all but the first of his features since the founding of the Lasky Company, and employed a team of five photographers for The Ten Commandments A sixth photographer, Ray Rennahan, was assigned to film scenes in Technicolor, but the director also continued to experiment with the expensive Hand-schiegl process that involved application of colors like pastel green and platinum yellow with stencilling upon completion of photography.[11] A 1918 report in Motion Picture News stressed improvement in this technique so that subtle effects were noticeable in the filmmaker's flashbacks and historical epics starring Geraldine Farrar, notably in The Woman God Forgot (1917) and The Devil Stone (1917). At the time, DeMille, asserting his role as a cultural custodian, claimed that "color photography. . . can never be used universally in motion pictures, for the eye of the spectator would be put to too great a strain, and the variety of colors would distract. . . from the story values." Five years later, however, Variety dismissed the Modern Story of The Ten Commandments because it was in "white and black" and remarked, "Were there some manner found to cut back to those enormous scenes in colors ·.. it would give the audience another look at what they really want to see in this picture."[12] In sum, the use of color in the Biblical Prologue accounts not only for the technical innovation of The Ten Commandments but also explains the high ratio of extreme long shots in the construction of a mise-en-scène that transformed the screen into an artist's canvas.

Although The Ten Commandments was one of the first productions to demonstrate innovative two-step Technicolor photography, two versions of the film at George Eastman House, including deteriorating footage of the director's own nitrate print, have color sequences achieved through application of the Handschiegl process. Paolo Cherchi Usai speculates that the

director preferred the painstaking stencilling procedure because its effects were more subtle than the less expensive Technicolor used for prints distributed to exhibitors. The transition from standard tinting and/or toning of footage to the Handschiegl process in one of the two prints occurs during scenes of the exodus. An extreme long shot shows Moses (Theodore Roberts) in the middleground as the children of Israel, whose numbers are so vast that they wind across the desert into the horizon, follow him into the unknown. Against the white sand dunes are splashes of color that distinguish items of clothing worn by various followers as they march in exultation. Cuts to several long shots of the crowd show individuals wearing costumes in bright orange and pink. The use of color for this particular sequence in DeMille's nitrate print, however, differs and is more calculated to render dramatic values in chromatic terms. As the Hebrews leave the City of Rameses, for example, a thin vertical strip of blue appears in the center of the screen and increases in width in succeeding shots until it blots out the sepia tint of the footage to convey a sense of liberation.[13] A sequence of masses of people walking into the desert that concludes with a fade-out leaving a blank screen in red, is toned in that color to give a sense of intense heat. DeMille intercuts between blue-tinted shots of Moses, standing with his followers as they complete their passage through the Red Sea, and the pharaoh in hot pursuit in footage toned brown and red so that color values differentiate two opposing armies. Symbolically, the massive stone wall in the background of the art titles disappears upon the liberation of the Hebrews, whereas a bright orange curtain of flames entraps the pharaoh and his chariots. An impressive scene that recalls the burning of the saint in Joan the Woman , it represents an effect the director visualized in terms of his first epic when he wrote "like Joan" on the shooting script.[14] Further signifying the clash between two radically different cultures are the elements of fire and water rendered in color and special effects. The pharaoh and his awed charioteer, outlined against an enormous, pastel-colored wall of bluish-tinted green waves, continue their pursuit between parted waters that eventually crash down on the Egyptian host.

As spectacular as the exodus, in essence a magnificent chase sequence, is the intercutting between scenes on the mount in which Moses receives the commandments and scenes in which the children of Israel succumb to bacchanalian revelry and worship a golden calf. DeMille showed his admiration for Doré, whose work remained an inspiration for his mise-en-scène throughout his career, by reproducing the barren, craggy landscape with sheer embankments that dominates so many of the artist's engravings. Again, the director uses color as well as low-key lighting to show Moses, mostly in extreme long shots tinted blue, hammering tablets on the side of a cliff as the words of the commandments appear like thunderbolts against a darkened and windy sky with flashes of lightning toned red. But at the very

36. As the lawgiver Moses, an icon inspired by Doré's illustrations,

Theodore Roberts receives the commandments on Mount Sinai while his

followers worship a golden calf. (Photo courtesy George Eastman House)

moment that Moses receives the law of God to establish a monotheistic patriarchy, his sister Miriam (Estelle Taylor), wearing a jewelled brassiere and serpent bracelets wound around her arms, is burnishing the golden calf in sepia-tinted footage. A symbol of paganism and depraved Orientalism that, it should be noted, is not mentioned in Exodus, she is suddenly afflicted with leprosy and declared unclean.

As allegorical figures symbolizing radically opposed male and female principles, Moses and Miriam are the only characters repeatedly privileged with medium shots that distinguish them as individuals in massive crowd scenes. DeMille did not resolve the narratological problem of historical representation as a macrocosm photographed in extreme long shots until he directed The King of Kings (1927). A flashback to the biblical era toward the end of the Modern Story of The Ten Commandments , interestingly, minimizes the "eclipse of distance" resulting from a cinematic as opposed to a theatrical articulation of space in terms of shot scale, camera angles, and editing. A recapitulation of the incident in which Christ, standing with his back to the camera, heals a woman afflicted with leprosy is photographed not only in extreme long shot but in low-key lighting so that the scene

resembles a tableau. Consider this shot in relation to a sequence in The King of Kings , photographed four years later and premiered at Grauman's Chinese Theatre, in which Christ (H. B. Carpenter) heals a blind girl. DeMille cuts from an extreme long shot of expectant travelers gathered outside the humble home of the carpenter to a series of medium shots and medium close-ups of the blind girl seeking to be healed. When she finally opens her eyes for the first time, the face of Christ comes into focus in a medium close-up that represents not only her point of view but that of the audience as well. A two-shot then shows the carpenter embracing the young girl in a moment meant to reinforce spectator identification with the Christ figure. By moving his camera in for medium close-ups and close-ups, DeMille humanized biblical characters and thereby bridged the gap between macrocosm and microcosm in historical representations. As in Joan the Woman , however, he adopted such a narrative strategy at the expense of historicity because he resorted to dramatizations that either were fictional or could not be authenticated. After this stage in the development of his narration in silent cinema, DeMille incorporated technological advances such as sound and widescreen, but his painterly style, which emphasized frontality or shots mostly perpendicular to the camera and minimal tracking, remained fairly consistent for several decades.[15]

In The Ten Commandments , DeMille's failure to resolve filmic narration with respect to the issue of microcosm versus macrocosm is evident in the film's two-part structure. Scenarist Jeanie Macpherson, interestingly, had considered a more episodic narrative in which the commandments would be broken in successive but separate stories until she decided on a Modern Story with a Biblical Prologue. A script that had not bisected historical time may have influenced the director to consider a representational strategy other than one that focused so much attention on the biblical era. Adolph Zukor, who proved himself wrong regarding the box-office appeal of the film, expressed concern about such an approach. Dispatching a telegram to Lasky, who was then on one of his trips to Los Angeles, Zukor noted: "CECIL'S PRODUCTION WILL IN ALL LIKELIHOOD HAVE AN EGYPTIAN AND PALESTINE ATMOSPHERE IT WILL HAVE TO HAVE A TREMENDOUS LOVE INTEREST IN ORDER TO OVERCOME THE HANDICAPS OF ATMOSPHERE I SUGGEST THAT YOU AND CECIL GO OVER THE STORY CAREFULLY." Attempting to reassure Zukor, DeMille, who had previously informed Lasky about his decision to film a two-part feature, wired back, "I can assure you. . . the picture will have those qualities of love, romance and beauty which you so rightly suggest . . . . [I]t will be the biggest picture ever made, not only from the standpoint of spectacle but from the standpoint of humaness [sic ], dramatic power, and the great good it will do."[16] As critics subsequently noted, however, the spectacle of the "Egyptian and Palestine atmosphere," whose preponderance of extreme

long shots did not encourage spectator identification, enraptured the audience while the "love interest" of the Modern Story, was eclipsed. In The King of Kings , DeMille introduced a "love interest," as he had in Joan the Woman , by inventing a fictional relationship between two of its principal characters, Mary Magdalene and Judas.

Despite its being overshadowed by the Biblical Prologue, the Modern Story is thematically related as a narrative about two sons, Dan (Rod La Rocque) and John McTavish (Richard Dix), who respond in opposite ways to the stern upbringing of a fundamentalist mother (Edythe Chapman). The sentimental melodrama begins with a dissolve from an extreme long shot of the children of Israel, terrified by the wrath of God, to a medium shot of the family gathered at a table for a Bible reading. The enormous size of the Bible indicates that it is most likely an illustrated edition, for the mother has been reading Exodus as dramatized in the Biblical Prologue. Dan, an atheist and a dishonest building contractor, eventually violates every one of the commandments to become rich and gratify his whims, including marriage to the woman his brother loves, Mary Leigh (Leatrice Joy), whereas John, a simple carpenter, represents the small-town values that are being eroded in a consumer culture. Although the Modern Story is old-fashioned and clichéd, it is more cinematic than the Biblical Prologue in its use of editing with respect to scale and angle of shots. At least two sequences are particularly striking. In the first, Mary rides an elevator inside the shaft of the construction site of a church to visit John, who is watching her ascend from the top of the scaffolding. Although John's point of view is represented in high angle shots, the audience experiences Mary's ascent in that her point of view is shown not only in repeated low angle shots but in vertical tracking shots of the city's skyline visible through the partially constructed church. As the elevator reaches the top of the scaffolding, the sky comes into full view before Mary alights to greet John. A second sequence focusing on a murder, detailed in the script and quoted by René Clément in Les Maudits (1946) and Alfred Hitchcock in Psycho (1960), is also striking in its use of low-key lighting, set design, and editing. Dan visits the exotic apartment of his mistress, Sally Lung (Nita Naldi), characterized as a "combination of French perfume and Oriental incense. . . more dangerous than nitroglycerine," to raise funds to stave off a building scandal that has already cost his mother's life.[17] Sally, obviously, is a modern counterpart of Miriam in the Biblical Prologue. After wresting from her a string of pearls that had been an extravagance in better times, Dan is horrified to read a news headline about her escape from a leper colony on Molokai. A long shot in low-key lighting shows Sally, costumed in a sequined gown with kimono-style sleeves and an ornate headdress, gloating as she stands by the draped doorway to the right. Seeking revenge, Dan fires his gun at her. A medium long shot shows the wounded woman react by reaching up to grab the portiere or

37. A male secretary prevents Leatrice Joy from interrupting a rendezvous

that her husband is having with his Eurasian mistress in the Modern Story

of The Ten Commandments. (Photo courtesy George Eastman House)

38. As a building contractor who breaks every one of the commandments,

Rod La Rocque is about to present Nita Naldi, "a combination of French

perfume and Oriental incense," with an expensive string of pearls.

(Photo courtesy George Eastman House)

drapery. A medium shot and then a close-up show the drapes slowly being torn off the rings to reveal an exotic statue of a Buddha in the background of the adjoining room. Dan has now broken every one of the ten commandments and meets his death in a watery grave—as did the pharaoh's mighty chariot host—in his attempt to escape to Mexico.

The Ten Commandments was premiered in major cities according to the following schedule: Los Angeles on December 4, 1923 (appropriately at Grauman's Egyptian Theatre), New York on December 21, Chicago on February 11, 1924, Philadelphia on February 19, Boston on March 10, and London on March 17.[18] Possibly, the expense of publicity and advertising as well as exploitation at first-run theaters at a time when Famous Players-Lasky was experiencing a financial crisis explains the staggered release dates. Prior to the film's opening in New York, the largest electric sign ever displayed in the city was constructed to show chariots disappear in a chase on the side of the Putnam Building located on Broadway from Forty-third to Forty-fourth Streets. Lasky wrote to DeMille, "We own the Putnam Building and so can devote this space. . . which. . . couldn't be bought for love of money." Audiences, including the notables and celebrities who attended the premiere at the George M. Cohan Theatre, saw gigantic tablets representing the commandments open outward on the stage before the first shot of the credits, showing rays of light emanating from slabs of stone, appeared on the screen. Such a presentation was very costly, as Zukor pointed out to DeMille, and "required an additional outlay of from One Hundred Fifty to Two Hundred Fifty Thousand Dollars."[19] Yet an enormous amount of publicity was necessary not only to stimulate box-office business but to influence critical reception that would affect subsequent runs in major cities.

A clamorous chorus of approval resounded in the New York newspapers following the premiere of The Ten Commandments . The New York Times asserted, "it is probable [that] no more wonderful spectacle has even been put before the public"; the impressive color sequences were "better and more natural than other such effects we have witnessed on the screen." The Modern Story, however, was dismissed as an "ordinary and certainly uninspiring movie" which, nonetheless, had some "eye-smiting shots." The New York Morning Telegraph, New York Journal , and New York Sun were not alone in reporting enthusiastic cheers and applause as a sign of audience approval. Critics in trade journals and fan magazines also engaged in hyperbole and repeated superlative assessments of the film. C. S. Sewell summed up in Moving Picture World , "This Paramount production easily occupies the position at the top of the ladder of screen achievements," but found that "forceful as is the modern story, it is the biblical section which makes the picture preeminent." Similarly, Adele Whitely Fletcher argued in Motion Picture Magazine that the Biblical Prologue, especially the color sequences,

represented "one of the most amazing and overpowering sights that we have ever witnessed or ever hope to witness" but had "small praise" for the Modern Story. A number of critics disagreed, however, regarding the merits of the latter. Oscar Cooper claimed in Motion Picture News that the prologue "as a spectacle. . . stands alone, because it employs screen artifice as it has never before been employed" but found the Modern Story "powerful, well-knit, and filled with extraordinary acting." Apparently at no loss for words, James R. Quirk proclaimed in Photoplay that The Ten Commandments was "the best photoplay ever made" and "the greatest theatrical spectacle in history"; indeed, he was even "spellbound" by the Modern Story. Lastly, Julian Johnson, who reviewed films for Photoplay before he became head of the Editorial Department of Famous Players-Lasky, wrote to DeMille, "the thing the critics missed. . . is the perfect simplicity of manner in the second part, the life-like details, the startling and realistic dramatic effects."[20]

Critical discourse on The Ten Commandments , especially unanimous acclaim for the Biblical Prologue as opposed to mixed reception of the Modern Story, gives evidence of cultural wars signifying ambivalence toward modernity within a broadly construed middle class and native-born working class. In effect, the Biblical Prologue with its intertextual references to historical pageantry, the King James Version of the Bible, Gustave Doré's illustrations, and news stories about Egyptian artifacts constitutes a form of highbrow culture. The Modern Story, however, is not only extremely clichéd in its characterizations but also marred by preachy and risible intertitles. John, for example, warns his wayward brother, "Laugh at the Ten Commandments all you want, Dan—but they pack an awful wallop!" Dan later counters, "I told you I'd break the Ten Commandments and look what I've got for it, SUCCESS! That's all that counts! I'm sorry if your God doesn't like it—but this is my party, not His!" As for Mrs. McTavish, who represents fundamentalist adherence to biblical literalism, the New York Times commented, "if an old mother reads her Bible it is no reason why a motion picture director should have her carrying around a volume that weighs about a hundredweight." (It was most likely an illustrated edition.) Variety simply claimed the Modern Story was "ordinary. . . hoke."[21] But if some critics and cultivated filmgoers found the second part of the film—which comprised roughly two-thirds of an approximate three-hour screening—a disappointment, many in the audience did not.

With the decline of the Red Scare and the passage of an immigration restriction bill that meant the end of most foreign-born peoples in the United States in a generation, cultural fissures within a middle class, broadly defined to include proletarianized white-collar workers, became more visible in the 1920s.[22] Although antimodernist and nativist sentiment prevailed among the elite as well as among the lower-middle and native-born working classes in small towns and rural areas, these groups were nonetheless

engaged in a cultural war. Foremost was the challenge posed to an increasingly secularized liberal Protestantism by religious fundamentalism. Whereas the custodians of culture responded to modernity by adopting "a shift from a Protestant to a therapeutic world view" that validated self-realization and thus accommodated the growth of consumer capitalism, segments of the lower-middle and largely nonimmigrant working classes resisted the encroachment of rationalization. American religious movements, as Nathan O. Hatch argues, have traditionally been characterized by a populist impulse that has operated on the periphery of highbrow culture. Forming an alternative subculture, fundamentalists thrived by building their own infrastructure or "extensive network of seminaries, liberal arts colleges, Bible schools, youth organizations, foreign mission boards, publishing houses, conferences, and camps."[23] DeMille's moralizing in the Modern Story, which condemns a consumer culture linked with degenerate Orientalism, undoubtedly appealed to fundamentalists in the country, albeit they, unlike Catholics, did not comprise a sizeable percentage of the urban film-going audience. Biblical literalism, in other words, constituted a usable past for social classes that, unlike the cultural elite, were unambiguous regarding the use of popular culture as a representation of their religious views.

Within a decade, DeMille, who began his career as director-general of a production company founded to resituate cinema for a sophisticated clientele, was addressing a mass audience that included fundamentalists as well as urban Catholics. The Ten Commandments , with separate narratives set in the biblical past and the present, marks a transitional point in that the director produced highbrow art at the same time that he addressed spectators who would have disapproved of the modernity of his early Jazz Age films. Yet the acclaimed Biblical Prologue, with its references to intertexts in middle-class cultural practice, itself represents a commodity form as spectacle for visual appropriation, however mediated across the divisive lines of gender, class, ethnicity, religion, and geographical region. Particularly noteworthy in this respect is DeMille's popularization of The Doré Bible , an expensive and prized edition that appealed to the genteel sensibility. As realist representations based on photographs of Jerusalem and research in the Louvre, Doré's engravings, unlike previous biblical artwork, became well known during the latter part of the nineteenth century. The rich detail of Middle Eastern art surely evoked Orientalist fantasies about traveling to distant exotic places and indulging sensual appetites. Also appealing to the genteel classes who valued performance in parlor games and social entertainment was Doré's sense of theatricality. At the time he was working on the biblical illustrations, the French artist was engaged in staging tableaux vivants for the court of Napoléon III.[24] The most salient characteristics of The Doré Bible —realism, Orientalism, and theatricalization—were therefore essential aspects of genteel middle-class culture. To the extent that DeMille popularized Doré's biblical representations, the religious iconography of

the elite became dominant but was in turn subject to the homogenizing forces of a consumer culture. In 1945, for example, a two-volume Catholic edition of the Bible, still based on the Latin Vulgate as opposed to the King James Version, was published with Doré's illustrations.[25]

Significantly, the most acclaimed aspect of the Biblical Prologue, DeMille's addition of color to the Doré illustrations, demonstrated the problem of cultural stewardship as practiced by the genteel classes. The use of color in visual media, as Neil Harris argues, became a problematic issue in that it not only signified the refinement and taste of the well-to-do but also constituted a threat to established traditions of iconography. Consequently, the employment of color was desirable only when it did not pander to the vulgar taste of the masses and thereby contravene highbrow culture as spiritual uplift. Such was the case in DeMille's Biblical Prologue. Yet critical discourse on color was only the latest expression of dismay regarding visual representations such as engravings and halftones that were technological advances associated with commercialism. As Harris points out, Harper's Weekly complained in a 1911 editorial, "We can scarce get the sense of what we read for the pictures." For decades, the elite classes had been expressing concern that the proliferation of visual media would debase established cultural forms.[26] Since silent cinema, with its narrative and dialogue intertitles, reversed the semiotic ratio or relationship between words and pictures in highbrow publications, as did advertising, it was indeed suspect. The Ten Commandments represented a magnificent triumph because DeMille showed that such a reversal could in effect constitute a form of highbrow art with didactic values. But he also demonstrated that culture was a commodity that appealed to a mass audience despite elitist efforts to preserve its sacrosanct status. Although Motion Picture News advised exhibitors to emphasize the selling point that the director's film would be "a positive benefit to civilization," eventually the cornmodification of spectacle would become divorced from the rhetoric of Victorian moralism and confirm the fears of the elite.[27]

Writing an account of the scripting of The Ten Commandments for a souvenir program, Macpherson unwittingly reinforced the concern of the genteel classes about the "deverbalization of the forum" that vitiated their concept of culture. She asserted, "'Seeing is believing' and we believed the spectator would be much more impressed with a story based on the Ten Commandments if he first had seen the history of them . . . during that faraway time of the birth of the Decalogue."[28] The scriptwriter expressed a viewpoint that endorsed the commodification and reification of the biblical past for visual appropriation by film spectators. DeMille's representation of religious experience as spectacle, not coincidentally, provided the advertising industry with intertexts on consumption as a form of self-fulfillment and uplift. When Bruce Barton, son of a clergyman and later a consultant for The King of Kings , characterized the function of advertisers in

millenarian terms, the translation of religious sentiment into profit was undeniable.[29] Such a development in an industry with a sense of mission to educate the public was not unrelated, however, to the sacralization of culture earlier sought by the elite in order to stave off vulgar materialism and debasement of traditional cultural forms. The rhetoric of spiritual uplift could readily be translated, in other words, not only to products of mass culture but also to advertising strategies that invoked religious doctrine while reifying social relations, surely a sign of a diminished sense of community. A local bank, for example, placed an ad in a souvenir program in which the commandment, "Thou Shalt Not Steal," was quoted to showcase an armored car as a device against those "too weak to resist. . . crime."[30] Appealing to uneasiness about pluralism as well as changing social mores in an industrial environment, the ad attests to lack of social cohesion, a continuing cause for concern among urban reformers. Yet genteel emphasis on spectacle in the form of visual displays and performance as a sign of breeding was not insignificant in setting the stage for alienated human relations in a consumer culture.

To sum up, DeMille's construction of the Biblical Prologue as historical pageantry and the Modern Story as sentimental melodrama was based on an antimodernist aesthetic, but the contradictions within that tradition were manifold. An heir to a theatrical legacy, the director was able to exploit intertextuality in genteel culture because film as spectacle was congruent with existing visual representations such as department store displays, world's fair pavilions, and civic drama, not to mention well-appointed middle-class parlors. "For the sake of appearances," however, was an expression that signified the moral ambiguities involved in simulation or dissimulation as a social and cultural practice. Ultimately, this distinguishing characteristic of genteel middle-class culture became the most essential aspect of what Guy Debord calls "the society of the spectacle." As Debord, following Lukács, points out, "the spectacle is the affirmation of appearance and affirmation of. . . social life as mere appearance." To put it another way, the reality, of the social relations of production is obscured or, to be more precise, "mediated by images" and rendered abstract. Accordingly, the representation of reality past and present as consumable images in The Ten Commandments testifies to the dominance of spectacle in commodity production. "The real consumer becomes a consumer of illusions."[31] Granted, the antimodernist tradition that DeMille represented was ultimately subverted by its own internal contradictions, but its legacy of spectacle as the ultimate form of cornmodification still reverberates in today's postmodern culture.

The Cost of Spectacle: Film Production as Commodity Fetishism

The Ten Commandments revived DeMille's sagging reputation as a filmmaker at a time when critics were lampooning his society dramas as outré spec-

tacles. Adele Whitely Fletcher observed in Motion Picture Magazine , "Just when humorists were finding in the DeMille tales of distorted society life ample material for their somewhat mordant jesting, he comes forth and blazes his name on the roster of the great." Fletcher herself had quoted an amusing line from Life when she previously objected to the director's excessive use of flashbacks: "Cecil B. DeMille has sent to India for seven hundred dancing girls, sixty-eight elephants, fourteen Bengal tigers and five maharajahs to be used in the dream episode of his forthcoming production of Sinclair Lewis' novel 'Main Street.'"[32] An analysis of the critical reception of DeMille's texts in another leading fan magazine, Motion Picture Classic , is representative of industry discourse and reveals why his reputation, which had consistently been equated with the advance of cinema as an art form, declined in the early 1920s.

In September 1919 Frederick James Smith announced a list of the ten best films of the preceding twelve months in Motion Picture Classic and cited four DeMille features: Don't Change Your Husband, For Better, For Worse, The Squaw Man (a remake of the famous original), and We Can't Have Everything . Smith repeated an earlier assessment in which he claimed, "Just now there's no director as satisfying as . . . DeMille" and praised him for "the most consistent directorial advance." A year later in August 1920, Smith listed DeMille's Male and Female and Why Change Your Wife? as well as Erich von Stroheim's Blind Husbands among the ten best films and noted, "Our biggest disappointment. . . lies in the fact that David Wark Griffith has contributed nothing material to the screen during the [past] twelve months." Perhaps most revealing was his complaint about DeMille: "Lavish and picturesque is his style, but the human note. . . is not there . . . . DeMille is running rife in boudoir negligee. His dramas are as intimate as a department store window." Continuing in the same vein a year later, the critic found "little real warmth and feeling" in Forbidden Fruit "because there is little of either in the DeMille method." Harrison Haskins had made a similar observation in Motion Picture Classic when he assessed the industry's "big six directors" in 1918: "DeMille falls short in sympathy . . . . He interests, but he doesn't make you feel. " When Smith reviewed Fool's Paradise in 1922, he described the film as a "mess of piffle" and declared, "Cecil deMille is fast slipping from his luxuriously upholstered seat as one of our foremost directors." After a five-year tenure as Motion Picture Classic's film critic, Smith yielded his byline to Laurence Reid, who promptly dismissed Adam's Rib (1923), a society drama featuring a flashback to prehistoric times, as "hokum." Assessing the top directors in 1923, namely, D. W. Griffith, DeMille, Thomas H. Ince, Rex Ingram, Eric von Stroheim, and Ernst Lubitsch, Harry Cart echoed in the fan magazine what had become a refrain in the industry: DeMille has "a silken finish that no other director has ever been able to approach" but his films "always impress you as a story told on a yachting party to well-bred hearers."[33]

A filmmaker whose earlier classics included titles such as Carmen, Chimmie Fadden Out West, Kindling, The Golden Chance , and The Cheat , that could scarcely be dismissed as set decorations with little human emotion, DeMille had become associated with camp and kitsch productions. Although the early Jazz Age films comprised a novel departure much imitated in the industry, critics responded to the director's continuing orchestration of spectacle with varying degrees of amusement, complaints about commodification, and, ultimately, boredom. An apostle of the consumer culture, like the ad men whose texts he influenced, DeMille gave every indication that he had been thoroughly seduced by film production as a form of commodity fetishism. Although it is impossible to ascertain how the exact figures for the costs and grosses of his features were calculated, the director kept a list, dated April 27, 1928, that gives evidence of the transformation of his filmmaking style in the postwar era. This statistical data is worth considering as an index of change signifying an increased obsession with producing spectacle in an extraordinary film career.

Average cost per feature (excluding Joan the Woman as a studio special) during DeMille's tenure as director-general of the Lasky Company remained fairly constant in nominal terms. The total figures are as follows: $15,450.25 in 1913 (for The Squaw Man ); $17,210.84 in 1914; $16,516.87 in 1915; and $17,760.88 in 1916. Assuming that these sums were not adjusted for inflation and using 1914 as a base year, I conclude that the director's production costs actually declined each year in terms of real dollars. After the merger with Famous Players in 1916, DeMille made two films starring Mary Pickford, whose exorbitant superstar salary inflated budgets so that Romance of the Redwoods (1917) and The Little American (1917) will not be taken into account here. Starting with the production of Old Wives for New in 1918, however, DeMille embarked on a series of all-star features as society dramas that meant relatively low overhead in terms of actors' salaries but escalating expenditures with respect to set and costume design. Average costs per film for each year in the postwar period are as follows: $59,587.36 in 1918; $144,639.88 in 1919; $258,130.04 in 1920; $258,001.05 in 1921; $396,271.89 in 1922; $1,475,836.93 in 1923, the year of The Ten Commandments ; and $405,516.49 in 1924. Adjusting these figures for inflation and excluding the year 1917 due to Pickford's salary, I conclude DeMille's production budgets increased at an annual rate as follows: 118 percent in 1918 (compared to 1916); 129 percent in 1919; 60 percent in 1920; 58 percent in 1921, a year when a worldwide depression actually meant deflation of the dollar; 55 percent in 1922; and 257 percent in 1923 (for The Ten Commandments ). Costs for 1924, DeMille's last year with Famous Players-Lasky, were similar to those accrued in 1922.[34]

Although Zukor noted in retrospect that DeMille was an exception to "those who had little respect for the men in the business end of the industry," the director's escalating production budgets caused tension that

led to a final rupture. As his filmmaking became increasingly focused on the consumer culture as spectacle, DeMille's correspondence with his longtime colleague, Lasky, became a series of negotiations about budgetary matters. At the end of 1918, the year in which he began to produce society dramas, DeMille wrote to Lasky about a $12,000 cost overrun for Don't Change Your Husband and claimed, "The average cost of my pictures to date . . . is $62,243."[35] Less than two years later, in the midst of protracted negotiations for a new five-year contract with the corporation, he wired Lasky:

I urge the contract provide for an expenditure of not less than one hundred and seventy-five thousand . . . per picture exclusive of weekly advances, the reason . . . being that Male and Female . . . cost one hundred and sixty-thousand. . . and cost of productions has gone up so that I do not want to feel that I must scrimp and pinch . . . and you know my productions are greatly dependent upon their lavish handling.[36]

A shrewd businessman, the director formed Cecil B. DeMille Productions as a partnership in 1920 to negotiate with Famous Players-Lasky for a percentage of net profits realized from the distribution of film rentals worldwide in addition to his usual weekly advances. Such a procedure resulted in considerable friction between the two organizations regarding production costs, accounting methods, audits, and division of profits. DeMille Productions, interestingly, branched out into real estate, securities, and other profitable forms of speculation in addition to filmmaking.[37]

While his attorney, Neil S. McCarthy, dealt with details regarding the relationship between his partnership and the corporation, DeMille continued to press Lasky regarding the budgets of his feature films. Despite a global recession, he wired in May 1921, "the increased magnitude of recent pictures not only of our own but of other companies make it necessary [sic ] for me to have . . . a minimum of three hundred thousand for each production not including the sixty five hundred dollars weekly" (his advance against a percentage of profits). The Executive and Finance Committee of Famous Players-Lasky countered with a memorandum that limited the director's expenditures to $290,000 including his weekly advances. Due to an economic downturn in the industry and to an anticipated reduction in film rentals, the memo stressed that it would be impossible for a picture to gross $900,000, the minimal amount required to show a profit. A decision to reduce the salaries of studio staff and actors and to cut production costs indicated the gravity of the situation at this time.[38]

A month later, Zukor, noting that DeMille had exceeded his budget for Fool's Paradise , stipulated in a modification of the director's contract that the negative cost of his next three productions was to be limited, excluding his weekly advances, to $150,000, $250,000, and $300,000, respectively. DeMille, calling attention to his reputation as "the most consistent money-maker in the business," wired in September, "I cannot and will not make pictures

39. Correspondence from Jesse L. Lasky, vice-president of Famous Players-Lasky

and DeMille's colleague for many years. (Photo courtesy Brigham Young University)

with a yard stick." Despite Zukor's contractual stipulations, Lasky continued to run interference for the director by securing approval from the Executive Committee for higher production costs even though he had warned him in October, "The company's policy for the next few months will be a most conservative one. There will be no expansion of any kind and. . . investment in theatres, etc. will be gotten rid of, so we can accumulate as much cash as possible." As Lasky confided in a more personal vein in his correspondence the following year, "you are luckier than I am, old fellow, as you can

always depend on me to go to the front for you. . . but I haven't anyone to help me out in my problems with the company."[39] In sum, DeMille's determination to acquire a greater percentage of the profits of his features as well as escalating production costs exacerbated his relationship with Zukor and placed Lasky in a precarious position as a middleman. Such a tenuous situation could not withstand the unprecedented cost overruns of The Ten Commandments .

When Zukor wired Lasky in April 1923 that he was convinced there should be elements of "love and romance" in The Ten Commandments , he also expressed concern that production costs had exceeded $700,000 even before shooting commenced. DeMille volunteered to waive his guarantee to a percentage of the film's profits but not his weekly advances. Zukor remained unimpressed. According to the director's account of events, as expenditures neared $1 million, a bill for $3,000 for the pharaoh's magnificent team of horses sent Elek J. Ludvigh, a corporation attorney, marching into Zukor's office and exclaiming, "You've got a crazy man on that. Look at the cost." Since DeMille served as a board member or an official of several California banks and was acquainted with A. P. Giannini, founder of the financial institution that became the Bank of America, he was able to outflank Zukor and raise $1 million to buy the production outright. A rupture between the two men was momentarily avoided as Zukor backed down, but DeMille's mounting expenditures, which eventually totalled $1.5 million, plunged the corporation into a severe financial crisis. The director agreed in the fall to a retroactive clause in his contract that would reduce the percentage of his profits from five previous productions. Less than two weeks later, Lasky informed DeMille that beginning on October 27, the studio would be closed for a period often weeks "on account of the excessive and mounting cost of production and . . . overproduction of pictures throughout the industry." DeMille responded immediately with a memo in which he listed salary reductions and layoffs affecting his staff. The director's decision to retain technicians at half-salary totalling thirty or forty dollars a week, surely a modest sum, and to dismiss clerical workers, seamstresses, and maids who earned even less gives an indication of the magnitude of his expenditures for sets, color processing, and special effects.[40]Motion Picture News headlined the story of the layoff of hundreds of Famous Players-Lasky employees not only at the West Coast studio but also in the New York home office, the Long Island studio, and Paramount's exploitation staff in the field. Carl Anderson, president of Anderson Pictures Corporation, astutely summed up the situation in the industry:

One unit pitted its resources against another, thinking to win favor by the lavishness of their productions . . . . Some producers have been on a wild orgy of spending . . . . There had to come a time when top-heavy production costs would tumble of their own weight . . . . As far back as June, 1921, the. . . Motion

Picture Theatre Owners of America [warned] that production costs were too high.[41]

A short piece about Famous Players-Lasky's denial that DeMille was resigning from his position as director-general of the West Coast studio appeared, interestingly, on the same page.

Although The Ten Commandments became a commercial success with gross earnings almost triple its cost, Zukor was determined to curb DeMille's threat to the financial integrity of Famous Players-Lasky when it reopened in January 1924. Since the director's five-year contract was due to expire in 1925, Zukor encouraged him to film his next feature, The Golden Bed (1925), at the Long Island studio so that they could both spend time with each other that would be "mutually beneficial and enjoyable." Unfortunately, that studio's facilities proved to be inadequate. As usual, Zukor employed Lasky as a go-between in negotiations and suggested that DeMille accept a lower weekly advance—S3,500 a week as part of negative costs negotiated in advance—and agree to a fifty-fifty division of profits between DeMille Productions and Famous Players-Lasky. Less than two months after this offer was tendered, trade journals simultaneously announced DeMille's departure from Famous Players-Lasky and D. W. Griffith's signing of a long-term contract with the studio in January 1925. After purchasing the Thomas H. Ince Studio in Culver City, DeMille began a new, independent, and short-lived phase in his career as the head of his own production company. But his situation was now comparable to the unenviable fate of Samuel Goldwyn upon the latter's ouster when the Lasky Company merged with Famous Players in 1916. As the director later recalled, "Mr. Goldwyn found himself without any organization at all—flat—nothing . . . . You cannot go out and pick up an organization."[42] DeMille negotiated a contract between his new studio and Producers Distributing Corporation, an organization that almost immediately merged with the Keith-Albee-Orpheum circuit of theaters, but he secured neither the financial backing nor distribution outlets to which he had become accustomed. Furthermore, in a replay of his production of The Ten Commandments , he spent two million dollars on The King of Kings and precipitated another severe financial crisis that led to his downfall.

Five years after he founded the DeMille Studio, the director abandoned his venture and began a brief tenure at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, a corporation that challenged the hegemony of Famous Players-Lasky toward the end of the silent era. Unfortunately, he made three sound films, including two remakes—Madam Satan (1930), a society drama featuring the Ballet Mécha-nique as well as a zeppelin, and a third version of The Squaw Man (1931)—that were financial disasters. In 1932 he returned to Famous Players-Lasky, now Paramount Publix Corporation, at a time when both Lasky and Zukor were being outmaneuvered in the latest executive power struggle. Although

DeMille, on the verge of bankruptcy and in the midst of litigation with the Internal Revenue Service, survived to win box-office if not critical acclaim with The Sign of the Cross (1932), the decline of his career in the interim underscores the importance of his earlier relationships with Lasky and Zukor. Undeterred in his obsession to mount increasingly lavish spectacles, DeMille had been seduced by film production as a form of commodity fetishism. As such, he represented a nonrational component in the industry in contrast to the sober-minded business sense that Lasky and Zukor brought to film as an entrepreneurial enterprise. DeMille thus contributed to the evolution of filmmaking as commodification in an Orientalist form, that is, the exercise of hypnotic power through the sheer accumulation of objects displayed as spectacle.[43] Indeed, the militaristic connotation of his title as director-general of Famous Players-Lasky signified that the orchestration of stupendous visual display was essentially another aspect of Western imperialism. The filmmaker, not coincidentally, wore jodhpurs and puttees as part of his costume on the set to project an authoritarian image. As opposed to the bureaucratic cost accounting procedures of entrepreneurialism, the Orientalist dimension of filmmaking as an irrational expression of power poses an interesting legacy for the industry today in its phase of multinational corporate competition that transcends geographical boundaries.

Demille's Legacy in a Postmodern Age: the Ten Commandments (1956) As a Televisual Supertext

The legacy of DeMille's silent cinema with respect to his productions in the sound era is best characterized as an antimodernist representation of history in the tradition of Progressive Era civic pageantry. Although commodified as spectacle for a mass audience, the director's historical films constituted a usable past by defining progress in Protestant terms and by reinforcing moral and patriotic values in times of crisis. During the economic downturn of the nation's worst depression and the beleaguered years of the Second World War and the Cold War, DeMille revitalized the tradition of Victorian pictorialism by emphasizing the relevance of public history for American citizens. Consequently, his outmoded filmmaking style, which articulated space according to theatrical as opposed to cinematic conventions, proved to be advantageous despite the ridicule it sometimes provoked among critics. DeMille, in other words, minimized the "eclipse of distance" characteristic of a modernist aesthetic and thereby reaffirmed the didactic value of his message. Yet at the same time, he continued to reinforce consumer values by representing history in Orientalist terms as a magnificent spectacle for visual appropriation. Such a representational strategy proved to be especially apt at a time when the United States emerged as a superpower

engaged in spread-eagle diplomacy and as a model of consumer capitalism. Consistently exerting an appeal that other filmmakers rarely surpassed, the director established a series of box office records with historical epics about Orientalized empires, such as The Sign of the Cross (1932), a bizarre narrative of martyred Christians in ancient Rome; Cleopatra (1934), a sumptuous vision of antiquity; and The Crusades (1935), a swashbuckler set in an era of Saracen conquest. DeMille also succeeded with Westerns, frontier sagas, and period pieces celebrating American national emergence, like The Plainsman (1937), The Buccaneer (1938), Union Pacific (1939), North West Mounted Police (1940), Reap the Wild Wind (1942), and Unconquered (1947). Fittingly, he culminated his career by returning to small-town American values, as in The Greatest Show on Earth (1952), and to the biblical past, as in Samson and Delilah (1949) and a remake of The Ten Commandments (1956).

A brief consideration of the acclaimed remake, which became one of the industry's three top-grossing films at a time when the studio system was in decline, attests to the relevance of antimodernist historical film for today's postmodern culture.[44] A three-hour, third-nine-minute version of the earlier Biblical Prologue photographed in Technicolor and Vista Vision, the epic is the only religious film that is regularly telecast during the Passover and Easter holidays each year. Why is this particular narrative recycled annually as opposed to other historical epics typifying a genre that ironically was exploited to counter television spectatorship in the 1950s and 1960s? What explains the continuing high Nielsen ratings of an antimodernist spectacle that should by all accounts be outmoded on the small screen? First, the film engages in direct address, an oratorical mode congruent with television commercials promoting consumption as personal fulfillment, in order to celebrate American freedom during the Cold War. Unfortunately, DeMille's two-minute stage appearance, initially shown before a foreword and a fade-out to the Paramount logo, is not televised. During this brief prologue, the director inveighs against tyranny and attests to the historical veracity of his work in a theatrical space prefiguring the epic as a tableau. Audiences do listen to DeMille during the course of the film, however, as he narrates the voice-over that describes the founding of a nation based on religious worship and human freedom. Second, despite the visitation of God's wrath upon the children of Israel for worshipping the golden calf and engaging in bacchanalian revelry, the biblical vision of the Promised Land as the land of milk and honey accords with the consumer ethos promoted on television. Picture-postcard shots of Moses (Charlton Heston) seeking refuge under fruit-laden palm trees, moreover, conflate the Promised Land not only with the United States as a "city on a hill," but with southern California as a site of cultural imperialism signified by the studio system. And lastly, as part of a televised "programmed flow" or "supertext" that reedits the epic so that its dramatic tensions are disrupted and resolved by com-

mercials as mininarratives, The Ten Commandments is translated into a post-modern electronic form. Constant interruptions of the exodus by ads for food products, beverages, and minivans produce juxtapositions that celebrate American products, cause unintended hilarity, and alter the meaning of the spectacle.[45] The referent of the film is thus no longer a construction of the past but a commodity.[46] Since the filmmaker broke box office records by commodifying history as spectacle for mass audiences, the disappearance of the historical referent or its displacement by a televised image of a product in a postmodern consumer culture is particularly apt.[47]

A director who was instrumental in legitimating film by establishing the correspondence of cultural forms in the genteel tradition, DeMille did not live to see his most enduring historical epic transformed into a postmodern commodity. Fortuitously, he died in 1959 on the eve of a watershed in American history' when a younger generation rebelled against the spread-eagle foreign policy that his frontier sagas and biblical films celebrate in the tradition of civic pageantry. DeMille's sound epics appear dated today because Victorian pictorialism is no longer part of dominant representations, but his legacy survives in the form of television commercials and infomercials as didactic texts and in theme parks with interdependent media reconfiguring or erasing the line between spectacle and spectator.[48] The innovative silent cinema of the 1910s and early 1920s, however, remains the most substantial part of the director's achievement because these texts not only inscribe middle-class cultural practice during a historic moment of transition but also document the evolution of feature film as an art form. As a whole, his work in successive decades continues to be instructive regarding the consumer ethos because it demonstrates that fabricating spectacle became a form of commodity fetishism involving both producer and spectator in a process of reification. Granted, the reception of genteel middle-class culture has been mediated by a variety of working-class and ethnic subcultures, but the increasing dominance of representation in twentieth-century economic, political, and cultural life attests to DeMille's enduring legacy as an architect of modern consumption.