Chapter Six

Paradigms of Pure Love

In contemporary Indian culture, obsessive passion seems to run riot: songs, dramas, novels, films, and magazines loudly declare the inexhaustible craving for romance. Western media images may have given a new face to "love"—an English word now heard everywhere in India. Yet the tradition of romance predates European influence and has strong roots in the lore of village society. In North India long before British incursions, performances popularized a number of oral tales, each focusing on a pair of pining lovers. The concept of love in these folk traditions is distinct from the courtly notion of erotic sentiment (srngara rasa ) of Sanskrit verse and the devotional love of religious poetry (premabhakti ). Indigenous and secular, it manifests itself in the dramas of the Nautanki theatre beginning in the middle of the nineteenth century and continuing to the present.

The prevalence of romantic tales presents something of a paradox in North India, as it does in other agriculturally dominated societies. Here and in other places, people view marriage as a pragmatic coupling of families, intended to reproduce clan lines, maintain the domestic economy, and safeguard the rearing of children. The separation of the sexes is the norm, secured through the institution of gender-assigned tasks and spatial divisions consonant with them. Marital alliances are settled early in the life cycle and lead quickly to the assumption of adult gender-specific duties. Romantic love stands in opposition to the rules governing appropriate marriage. The union of hearts and bodies by mu-

tual individual choice is rarely approved, and it may be punished by the strictest measures.

Western opinion often concludes that in such societies "love" is an impossibility. In consequence it interprets their love stories as compensatory outlets for repressed emotional and sexual urges, ways of living out imaginatively an experience for which there is scant opportunity. Although plausible to a point, this view assumes dichotomies between thought and action, imagination and behavior, that may jeopardize an understanding of the cultural construction of love in North India. "Real" and "imagined" love are not essential opposed categories in the Indian tradition. As this chapter will soon elaborate, love becomes most real, most true and compelling, when it takes complete hold of the imagination, even subverting the mental faculties and preventing their normal functioning.

Rather than documentation of a sublimated fantasy, what the Nautanki dramatic literature may offer is evidence of the complex ways in which society responds to the emotional lives of its members. The tension that arises between a pair of lovers and their families is one that is amply depicted in these plays, indicating a strong push and pull between individual interests and the group loyalties focused on units of caste, clan, and community. The love experience frequently seems to oppose and undermine the hierarchical order, yet in other situations the social body incorporates it into a more harmonious whole. Once more the Nautanki play, through its concrete embodiment of character and incident, explores the moral dilemmas around a difficult issue that touches each spectator. In this process, it ultimately affirms the capacity for loving as an indispensable part of being human.

The Paradigm of Pure Love

Romantic love is preeminently a condition of the heart and is widely acknowledged to be an experience that takes the form of visualizing, yearning, and formulating future plans. The North Indian love complex builds on this foundation by accentuating the intensity of love and the emotional upheaval brought about by its occurrence. In the North Indian romances included in the Nautanki literature, the best example of the intense love experience is that found in Laila majnun (fig. 16). Majnun means "crazed person, madman." The narrative tells of the transformation of Qais, under the influence of love for Laila, from a respected

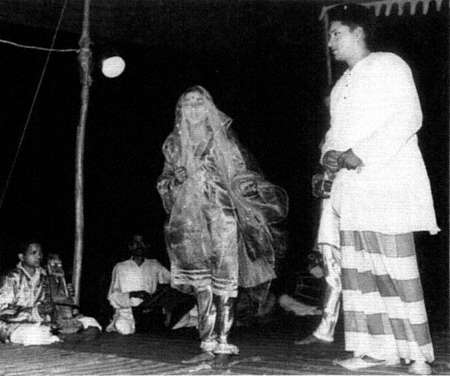

Fig. 16.

A meeting of the lovers, from Laila majnun . By permission of the Sangeet

Natak Akademi.

noble to Majnun, a demented beggar who wanders in the forests and wastelands searching endlessly for his beloved. The Nautanki version places an almost equal emphasis on the female's experience and allots to Laila an equivalent share of devotion and passion along with an explicit account of the societal obstacles to her pursuit of love.

Qais is the son of Amir of Damascus, and in Najd rules Sultan Sardar, whose lovely daughter is Laila. Both Laila and Qais attend the same school, and a great love grows between them. Qais loses interest in his studies, spending his hours chanting Laila's name; Laila's family on learning this withdraws her from school.

Distraught at the separation, Qais soon earns the scorn of the townsfolk and is treated as an insane person. Hearing of his son's infatuation, Qais's father takes a proposal of marriage to Laila's father. The families are social equals, but Laila's father is unwilling to marry her to a madman. Qais is invited to the house so that the women may test his mental competence. Qais performs well until he spots Laila's dog, whereupon he loses all semblance of balance and, lavishing hugs and kisses on the animal, releases his crazed passion and scotches his marriage chances.

Qais, now Majnun, takes refuge in the wastes beyond the city walls where he wanders, heartbroken. He encounters Naufil, who offers to help him defeat Laila's father in battle. Unfortunately, they lose the contest. Soon after, Laila is married off to Khushbakht, prince of Delhi. Laila continues to long for Majnun and has nothing to do with her husband. She is ejected from her husband's home and goes to the desert to look for Majnun. In the meantime, Majnun has heard of Laila's marriage and reached Delhi. The two lovers finally meet in the desert.

Their happiness is short-lived. On nearing the city, the pair are spotted and Laila is forcibly taken home by her mother. She is unable to survive the separation this time and pines away to death. When Majnun hears this news, he kills himself in grief. The two lovers are finally united in heaven. The city people bury their bodies next to each other and sing high praises of their immortal love.[1]

This tragic romance with its ending of dual death originated in the Arabian peninsula in the eighth century and has sustained popularity through the centuries in folk and courtly renderings all over the Islamic world.[2] Within the Nautanki repertoire, it functions as the prototype of a body of similar romances, its characters being cited frequently within other texts by both aspirants to and opponents of love. Several aspects of the text's treatment of love deserve special note, insofar as they link the tale to others similar to it. First is the spontaneous and unpremeditated nature of Qais and Laila's love. Their feeling for each other arises

naturally, when they meet at a young age. The instantaneous origin of true love is often represented in folk romance by such beginnings as an early meeting, the appearance of the loved one in a dream or sight of the painted picture of the beloved, or even the mention of the beloved's beauty and fame. The second characteristic is the complete constancy of the lovers and their devotion unto death. Their love for each other never wavers; they are completely loyal. They spend their entire lives in quest of union, abandoning all other concerns. No obstacle is too great, no misfortune too daunting. Third, the love depicted here is a mutual love. Laila boldly declares her attraction and is as unwilling to be separated from Majnun as he from her. She leaves her forced marriage to go join him in the desert and is the first to die of grief at being parted from him. Fourth and paramount, the tale tells of thwarted and obstructed love. Just as surely as Laila and Majnun's love is perfectly matched and steadfast, it is unattainable. Although the lovers finally spend a brief time together in the desert, society intercedes time and again to separate them. True union comes only after death, their total dedication to each other having removed them, as it were, from this world into another.

All these characteristics lend their love a pure, perfected quality, identified within the tradition by the phrase pak ishq (pure love).[3] An almost unrealizable ideal is supported here: love that is the excessive outer limit of human feeling and attachment. To this romantic ideal the drama counterposes the many obstacles encountered by the lovers as they strive for the fruition of their love. Although some versions mention a preexisting tribal feud between the lovers' families, opposition from Laila's family constitutes the primary impediment in the Nautanki account.[4] This opposition is based on the linkage of clan honor to effective control of female sexuality. The family's preoccupation with izzat (reputation, honor) necessitates "protecting" Laila, preserving her in a chaste and chastened state until a suitable marriage is contracted. The family's fear of losing izzat causes them to withdraw her from school to prevent the lovers from meeting once their love is discovered. Qais is then proposed as a possible marriage suitor and is almost accepted; love may be contained by the institutional forms of society if the lovers are of compatible rank. After Laila's marriage to Khushbakht, however, the chances of the pair's love reaching any socially acceptable outcome are reduced to naught. The natal family's surveillance is replaced by the concern of Laila's affines. They find in her a tarnished unwilling bride and turn her out. When she later meets Majnun, her own family hounds

her, wishing to confine her at home, even though her behavior would already have irreparably damaged their reputation. At every turn, her movements are controlled by physical force, but psychological coercion is imposed as well. The play is full of parents' and elders' preachings about female virtue, the importance of family honor, and the social necessity of marriage, all directed to Laila and intended to alter her attachment to Majnun.

The restraints imposed on Laila as a woman in patriarchal society are not present for Majnun as a male. No one attempts to confine him; on the contrary, the text's creators allow him—even force him—to roam far and wide. His unimpeded movement perhaps expresses the unbound freedom of the human spirit in love, although the text also describes him in cliched terms as ensnared, entrapped, and shackled by love's bonds. Nonetheless, as Laila does, Majnun incurs a loss of reputation, although of a different and finally more devastating kind. Whereas Laila is rebuked by her immediate family, Majnun becomes an object ridiculed by society at large. His love and the distraction it brings cause him to slight convention, to behave in inappropriate ways. For this he is taunted and labeled a madman, and he plummets rapidly to the level of an abject beggar. Laila is forced back into the confinement of the family; Majnun is pushed out of society altogether. He is ostracized and exiled to the jungles and wastelands. Through this action, the text asserts that excessive love (which pak ishq is by definition) is also transgressive. It violates the social order, alienating the lover from the ordered balance of human relations. On the one hand, it drives the lover as a social being beyond the pale, making him an outcaste, despised and lonely. On the other, it leads the lover's mind and heart into a territory of untamed feeling, into jungles of overwrought emotion and waste-lands of unfulfilled longing.

According to our text then, the experience of love (even, or especially, unfulfilled love) poses a tremendous threat to the social relationships of both parties. In the case of the woman it endangers the standing of her entire family and clan, while for the man it puts at risk reason and human companionship. The only place for romantic love is in an existence contrived beyond society's boundaries—in the barren wilderness, or in heaven. The profundity of society's opposition to the violation compassed by love emerges most forcefully in the tragic endings of many of these narratives. Society exacts its revenge on errant members not only by confining and exiling them, but ultimately by killing them. In most of these stories (and in some versions of Laila majnun ), betrayal

figures in this stringent end. The first death occurs when a lover gives up all hope after an antagonistic relative spreads a rumor of the other's death; this leads to a double suicide—each dying for the other, but in falsified circumstances. The treachery motif relieves the lovers of the burden of individual responsibility for suicide and accentuates the malicious and desperate opposition of family and society. In this way, the romantic dramas consistently pit the lovers against family and society in an unequal match, where the superior strength of the many acts against the isolated, separated couple.

From the viewpoint of the larger community, the validity of the family's claims and the apparent necessity of renewing the social order seem to lend moral weight to those who oppose the lovers. Yet the lovers' commitment to each other is not condemned but is commemorated in the Nautanki text: the lovers are the heroes, and society is the villain. How does the cause of love gain the moral force necessary to transform Laila and Majnun from antisocial deviants to cultural icons? The predictable answer, in Indo-Islamic scholarship, would be to refer to the mystical allegory of earthly lovers as seekers of the divine. Stories like Laila majnun, Shirin farhad , and Hir ranjha come out of the mystical tradition of Sufism, which identifies the lover with the seeker for eternal truth and the beloved with God. In Sufi-inspired literature, the experience of intense love becomes a way of understanding and describing the soul's desire for God. Both love-objects—God the divine beloved and the earthly beloved—are impossible of attainment. Both quests lead the seekers into peril, infamy, even madness and death. The mystical meaning of the romantic text, according to this view, directs the reader to a higher level of truth, which transcends the social ("mundane" or majazi ) experience of love to appear as a metaphor for the eternal ("real" or haqiqi ) love of humans for God.

Such an interpretation no doubt often accompanies the reception of love stories like Laila majnun in North India today, especially among the educated and orthodox circle of believers. The curious fact, however, is that our Nautanki text is noticeably lacking in mystical references. The spiritual allegory is not made manifest; Majnun is never designated as a seeker for God. Majnun simply asks God to help him, that is, to bring him Laila or end his life. During the lovers' separation, there is no mention of the mystical overtones of separation by the characters themselves, the narrator, or a third party. In the absence of an explicit allegory, the tale might still be interpreted mystically by knowing auditors. What seems more obvious, however, is that the earthly romance

of the lovers provides sufficient ground for a self-contained narrative at the folk level. An apparatus of translation into Sufistic terms is not necessary to the identity or popularity of the Laila-Majnun tale.

The Lover as Renunciant

Largely shorn of its mystical import in the Nautanki theatre, Laila majnun nevertheless preserves one important motif associated with both the Hindu and Sufi saintly traditions—and that is the characterization of the lover as a yogi or fakir. As in the texts of Gopichand and other renunciant kings, the two terms, signifying the ascetics of the great religious traditions of Hinduism and Islam, are used interchangeably by Nautanki poets. By the nineteenth century, the persona of yogi or fakir had become a multivalent referent employed in many narrative contexts. The figure was often conjoined with the icon of the righteous king, as discussed in the previous chapter. The disguise of the renunciant was also used in dramatic situations where deception was the intent, for example, for traveling incognito, infiltrating an enemy's ranks, or entering the women's quarters of a palace. The ascetic ruse played on North Indian society's suspicion of false (and true) ascetics as well as cultural obligations to provide for their maintenance through alms.

Almost universally in late medieval romance, the renunciant role additionally served to convey something of the excessive, selfless nature of romantic love. The lover is invariably compared to a yogi or fakir, and in many instances he takes on the attire of the renunciant either as a temporary expedient or, in a deeper transformation, for life. Even in the popular Indian movies of today, the unshaven gaunt visage of the hero is semiotic shorthand for the yogi or fakir, signifying "rejected or out-caste lover." Interestingly, North Indian romances at one time extended the assignation to love-crazed women as well. The abhisarika of Sanskrit lyric poetry—the woman who ventures abroad seeking union with her lover—was converted into the jogin —a female ascetic who makes a journey, enchanting men with her singing and playing musical instruments: an amalgam of Kali-like gruesome physique with the charms of the apsara (heavenly singing girl in classical Hindu mythology). Unlike the jogi , the jogin appears to have fallen by the wayside with the revision of gender roles in the modern period; other less ambiguous temptresses have usurped her place in cinema and popular culture, if not entirely in folklore.

Returning to the Laila majnun text, we can see how the representa-

tion of the lover as a fakir ennobles his character and highlights the selfless nature of his quest for Laila, building into the text a morality that may have Sufi antecedents yet is not overtly mystical. Like the avowed renunciant, Majnun gives up his attachments to possessions, to his good name, to his kin and community, even to sanity. His search for Laila carries him beyond the gates of civilized society to the edge of the desert, where he lives a hand-to-mouth existence without thought of his own well-being. The religious mendicant is held up as a cultural role model of the egoless search for truth, and Majnun's dedicated resolve and self-abnegation are exemplary traits that qualify him for the life of renunciation. Nonetheless, it would be shortsighted to deny the negative aspects of the fakir figure. Even though the yogi or fakir chooses to renounce the world, an aura of rejection by society envelops him. The beggar, the seeker of love, may be praised for his selfless suffering, but he is also despised, spurned, and taunted for his unconventional appearance and eccentric behavior. The extreme deterioration in Majnun's condition evokes a response of avoidance and disgust, not only in the townsfolk who stone him, but even in the largely sympathetic audience. In this manner the guise of fakir gives palpable shape to the idea of the lover's degradation, a major theme that recurs in many genres of Indo-Islamic literature.

Above all, what renunciation carries here, as in Nautanki texts like Gopichand , is a powerful affective component of sadness, despair, pain, and loss. Majnun in the desert is the human spirit in anguish—tormented by failure, by hopelessness, by abandonment. The sufferings of Majnun, like the sufferings of Job or Harishchandra, sustain the narrative on its pathos-driven course. Once more, according to the emotional syntax of folk narrative, degradation leads ultimately to apotheosis. Carried to its dramatic extreme, the pity that Majnun evokes converts to exoneration and veneration. The plot flipflops and suddenly catapults the lovers through the double suicide into the orbit of the immortals.

In short, the slippery ambiguous figure of the yogi or fakir encodes a complex set of messages communicated by the folk theatre (and North Indian society's other cultural forms as well) on the subject of romantic love. Love is uplifting but also demeaning; it is socially unacceptable, yet it purifies the spirit and finally transforms. In his search for the beloved (or more abstractly, for the experience of love itself), the lover is judged and judges himself by the highest moral standards: he must be constant, vigilant, ever willing to suffer. Steeling himself to a stern inner

discipline, his goal is nothing less than the perfection of his own being as much as union with another. Yet his diligence brings him into open conflict with society, and he suffers rejection on all sides.

Running through this tremendous idealism and moral fervor surrounding love is a dark commingling of compulsion and tragedy. Although the life of the lover may be the loftiest objective of human effort, the end of the lover's existence can only be death. The lover is compelled to love, driven by a destiny beyond conscious control. Commitment to the path of love allows no alternative, no turning back. Despite the travails of the most dedicated lover, separation remains as the unwavering condition of being in the world. Union with the beloved is a state one never experiences during an earthly life. Love is in no terms an impossibility: rather it is the distinguishing mark of the human condition. It rages through human consciousness, demanding the ultimate in commitment, the best that is within us. Yet as long as we exist as human beings, we are trapped in a state of imperfection, and we fail.

The exacting requirements of love, the lover's difficult passage through sufferings imposed from within and without, and the dim possibility of success—all are implied in the notion of love as renunciation and the lover as renunciant. That these themes are not limited to stories of Islamic origin is confirmed by other romantic tales in the Nautanki corpus. The tale of Sorath and Bija, found in Sang sorath , one of the oldest texts in the Svang collections, has a provenance extending from Rajas-than through Gujarat and Saurashtra. It lacks Islamic characters and references, yet undertones of unhappiness, loss, and tragedy mark the romantic chain of events.

Sorath, born under an unlucky sign, is abandoned by her father and brought up by a low-caste potter. Because of her beauty she is desired by several men, but she never finds a secure home. In her youth she passes from hand to hand, being sold to a wandering trader (banjara ), kidnapped by one king, and lusted after by another. Finally her true lover, Bija, embarks on a quest to rescue her, assuming the attire of a yogi seeking alms (bhiksha ). The two profess their mutual love and eventually escape from captivity together. On returning to his homeland, Bija is asked to surrender his beloved to his uncle the king and forced into exile. When he returns to the palace as a peacock, the king recognizes and shoots Bija. Seeing the only man whom she loved dead, Sorath immolates herself to become a sati .[5]

This story offers a moving account of female misery. The themes of misfortune, abandonment, and abuse all converge on the heroine, So-

rath, who seems to represent what happens to a woman when she loses the protection of her male kin. Many men covet and desire her, but no one stands up for her. Nevertheless, through her own inner truth, her sat , she survives the circumstances into which she is thrown and cultivates her personal sense of virtue. The trials she endures in the early part of the story prepare her, as it were, purifying her for a genuine experience of love that redeems and literally frees her from her chains.

As in Laila majnun , society's opposition to the pursuit of romantic love is represented by the obstacle of other males who claim possession of the heroine and confine her. The true lover, Bija, is distinguished from his rivals by his moral superiority: his courage, perseverance, and humility contrast with their rough arrogance. In appearing as a renunciant, Bija outwardly expresses the transfiguration that love may induce; he has taken on the life of self-denial, whereas the other suitors remain traders and kings, masters only of wealth and power. In the end the tyranny of the king does manage to snuff out the pair, yet their joint departure for another realm encodes the immortal nature of love. Tragedy is again a vehicle for lauding the most difficult and worthy of human aims.

A similar structure manifests itself in the great romance of the Punjab, Hir ranjha , a widely known folktale also performed as a Nautanki play.[6] The earliest extant version was composed by Damodar at the time of Akbar, and in that account as well as the Nautanki telling the lovers live together happily at the end although their circumstances differ. According to Damodar, Hir and Ranjha journey as fakirs to Mecca where they attend at the grave of the Prophet, whereas in the Nautanki they live peaceably with Ranjha's family.[7] However, in the most literarily respected version, that of Waris Shah, as well as in most variants, the tale concludes tragically.[8] Hir's uncle treacherously poisons her and Ranjha dies of grief, in the classic double-death pattern. Regardless of the variation in endings, all versions recount the depth of hostility between Hir's family and the lovers, which as we might now expect includes an attempt to marry Hir to another man. In all variants, the character of the lover Ranjha acquires vigor and persuasive power through his yogic leanings. We briefly summarize the Nautanki plot because it differs from the well known Waris Shah text on a number of points.

Hir and Ranjha are the offspring of noble families from Jhang Shiyala and Takht Hazara respectively. Appearing one night in each other's dreams, they fall deeply in love. Hir's distraught condition comes to the attention of her family members, who respond with lecturing and

abuse. Her brother, Patmal, threatens to kill her if she shames the family. A folk healer (baba ) is sent to cure Hir, but instead she persuades the baba to deliver her message to Ranjha.

Learning of Hir's whereabouts, Ranjha prepares to leave to find her. After many warnings and outpourings from his family and friends, he manages to depart. Dressed as a mendicant jogi he crosses various hurdles and eventually reaches Hir's garden, where he encamps until Hir comes to him. The lovers decide that Ranjha should go to work for Hir's brother, Patmal, as a cowherd, so that they may continue meeting regularly. This plan succeeds, and every day when Ranjha takes the cows to the fields to graze, Hit goes to meet him.

One day the lovers are discovered. Patmal tries to kill Ranjha by sending him into a beast-infested jungle. Fearing for Ranjha's life, Hit follows him in the guise of a jogin . With the protection of his seventy saints, Ranjha overcomes the vicious animals, and the two lovers meet once again. Patmal now sends Karnu Shah to capture Hir, promising her to him in marriage. Karnu and his men are easily defeated by Ranjha. The lovers, united at last, set off for Ranjha's home, where they find welcome in his family, get married, and live happily ever after.

Except for its conclusion, the Nautanki drama works within the same parameters of romantic love as Laila majnun and other texts, including the Waris Shah poem. If the love of Hir and Ranjha is excessive and overweening, it is also spontaneous and natural: the scenes of the lovers disporting in the fields with the grazing cattle strike pastoral tones that heighten the contrast with the oppressive dictates of clan and kin. The mutuality of feeling from love's inception is another important element, a pattern that appears in Indo-Islamic romances yet is absent from lyric genres such as the ghazal , where love is one-sided and the beloved assumes a haughty and cruel posture. Both fall simultaneously in love in a dream, but in the Nautanki it is Hir who first manifests the familiar symptoms of love's intensity, risks her position in the family, and makes the initial contact through a messenger. Disguised as a jogi , Ranjha journeys to her garden to meet her, and she in turn follows him to the forest in the role of a jogin when he is threatened by Patmal. She boldly escapes from home every day to meet her lover in the fields and repeatedly demonstrates her cleverness in plotting various stratagems to meet Ranjha. In the Waris Shah account, the opening events are somewhat different. Ranjha, the unfortunate youngest brother, is cheated out of his patrimony and leaves home to seek his fortune. He meets Hir at the river Chenab, and they fall in love at first sight. Hir demonstrates her

boldness by taking Ranjha home and getting him a job as the family cowherd.

The strength of Hir's character is matched by superlative traits present in the hero Ranjha. In the Nautanki version, special powers accrue to Ranjha as a result of his protection by seventy saints (sattar pir ). Thanks to divine guidance he is capable of performing a series of magical feats in his quest for his beloved.[9] To pass the baba's identity test he produces milk from a virgin cow. On his way to Hir's garden he crosses over a river seated in the lotus position without a boat. He later kills lions and beasts in the jungle and defeats Karnu Shah's army singlehanded. In all these instances, Ranjha's contact with the supernatural assists him in proving his valor, loyalty, and merit as the true lover of Hir. It also endows his personage with a mysterious attractiveness. Ranjha's powers, whatever their source, are superior to those of ordinary men, and his second identity as jogi lends him charismatic appeal, if not precisely moral authority.[10]

The fortitude of asceticism, the magic protection of the saints, the fiery passion of Hir—all are needed in the series of confrontations between the lovers and society. The suspense in the narrative is largely constructed of recurring episodes of family opposition that threaten the couple's relationship. In the Nautanki, the chief upholder of family honor and instigator of the trials that besiege the lovers is Hir's brother, Pat-mal. He insists that his sister's actions bring ill repute (badnami ) to himself and his family, and he assaults her with vile terms of abuse. Predictably he strives to arrange a marriage for Hir, handing over control of her movements to a husband, but the plan fails because Karnu lacks the superiority of arms (and character) to defeat Ranjha. Waris Shah provides a much more complicated series of incidents. The lover's chief opponent is Kaido, Hir's uncle; Hir's marriage, previously arranged with Saida, takes place but does not achieve its purpose of ending the lovers' involvement. Following the marriage, Ranjha visits Hir's town as a yogi, and eventually the lovers elope. The lovers are captured, Ranjha is exiled and Hir returned to her husband's clan. However, Ranjha's curses set the town on fire; fearing supernatural punishment the chief of the clan orders that the marriage of Hir and Saida be annulled. Hir and Ranjha prepare to marry at last. Even as Ranjha approaches Hir's home with his wedding party, Hir's brother and uncle poison her and she dies. Waris Shah's elaboration of plots and counterplots reiterates the structural opposition between the pair and society, highlighting the tenacious endurance of love against the most severe

odds. The poet also brings out the dynamism in rural society, in that shifting alliances of elders and friends alternately support and castigate the lovers, and the possibility for rapprochement exists until the end. Nonetheless, the stress imposed on the social fabric is beyond containment. The events tend toward rupture again and again.

Love across Boundaries of Caste and Class

The romances discussed so far feature a pair of lovers who are by birth social equals. In two of the tales, the hero after falling in love declines in rank, becoming unfit as a marriage partner for the heroine: Majnun goes mad and becomes a destitute beggar, Ranjha works as a cowherd and servant to Hir's family. Other Nautankis accentuate the transgressive nature of romantic love and bring out the theme of the lover's self-surrender by situating the lovers in different classes or castes. In these stories, the beloved is ordinarily a princess or daughter of nobility, whereas the lover may be a merchant, an artisan, or other social inferior. It should be mentioned that hypergamy is the normative pattern for marriage in North India, that is, alliance of a groom with a bride whose family is of somewhat lower rank. The transgression inherent in the romantic liaison between the high-born female and lower-born male has two possible outcomes in the Nautanki plays. It may provoke an act of treachery leading to the deaths of both lovers—the tragic pattern of earlier narratives—or it may lead to an execution threat and a redemptive counterstrike by the beloved, followed by marriage—a melodrama with a happy ending.

In Shirin farhad , an example of the former type, the stonecutter Far-had falls in love with queen Shirin while engaged in building a canal for her. Shirin's paramour, the king Khusro, hoping to get rid of his rival, assigns Farhad the task of digging a tunnel through an impenetrable mountain. Farhad recites Shirin's name continuously to invigorate himself, passes the difficult test, and wins her heart. Khusro then plants an old crone who falsely bewails Shirin's demise, causing Farhad to commit suicide; Shirin follows him soon after in death. The lovers Shirin and Farhad, often quoted in the same breath as the example of Laila and Majnun, embody the same brand of intemperate passion that knows no social boundaries. The character of Shirin is particularly impetuous in the Nautanki version; she rides forth to find Khusro when they are courting and later takes a bold stand, pursuing Farhad despite the difference in rank between them. She also manifests a certain degree of

haughty disdain: at first she rebuffs Farhad and demands that he earn her love. The act of carving through an obdurate mass of stone remains as a striking metaphor for the pursuit of romantic love in North Indian society—the tunneling underground matching the surreptitious designs that lovers must implement to break through society's massive resistance.[11]

Another early addition to the Nautanki repertoire, and an example of the melodrama plot, is Saudagar vo syahposh . This is the tale of a merchant's son, Gabru, who attempts to win the hand of Jamal, the daughter of a minister of state, after being enchanted by hearing her read from the Koran. While visiting Jamal, Gabru is apprehended one night by the king, who is touring the city disguised as a police constable to ensure its safety. Gabru is sentenced to hang; at the scene of the gallows, he waits anxiously for a final vision of his beloved. Jamal at the last moment appears dressed as a man all in black (syahposh ), riding a horse, wielding a dagger and sword. She threatens to commit suicide by stabbing herself or drinking a cup of poison. The king is persuaded of the true love of the couple and marries them on the spot.[12]

A similar tale of perilous love between a highly placed valorous woman and a commoner is Lakha banjara , which relates the love between a princess and Lakha, the son of a trader.[13] Reminiscent of Syahposh in many details, it culminates in Lakha's being arrested by a policeman while returning from the princess one night, his death sentence by the king, and the appearance of the princess at the gallows to plead with her father for her lover's release. In this story, however, the king does not relent. Lakha is killed, and the lovers are united only after Guru Gorakhnath arrives and resuscitates the dead Lakha. The final events of these two tales are remarkably close to those of Nautanki shahzadi . After the discovery of the affair between the princess Nautanki and Phul Singh, Phul Singh is sentenced to hang. As he awaits his execution, Nautanki suddenly arrives at the gallows, dressed as a man and armed with sword and dagger. She pulls out a cup of poison and prepares to commit suicide, vowing to die as Shirin died for Farhad and Laila for Majnun. As the executioners advance to pull the cord, she rushes with her dagger and drives them off. She then turns her sword on her father, demanding he pardon her lover immediately. The king consents to the marriage and the two are wed at once.

Although details differ, these stories all involve a romantic quest fraught with danger. The danger is expressed not only in the lover's travails in reaching the princess and obtaining her consent to love, but

in the life-threatening sentence meted out for the violation of an upper-class woman's honor. The social distance between the lovers increases the risk, particularly for the male. His transgression offends the law of the land and must be punished with execution by the king, while in earlier narratives the opposition was primarily from family and clan and never involved a criminal charge. The high-ranking female, in contrast, ignores family censure and has the liberty to behave in even imperious ways. In each case, the princess becomes her lover's rescuer. She braves public opinion, daring to leave the seclusion of her palace and appear in public; she challenges the chief representative of society's moral order, the king or her father (frequently one and the same), pleading for permission to marry and even threatening violence against him. To carry out her brave resolve, she may adopt the avenging persona of the virangana , the woman transformed into a warrior figure outfitted with weapons and riding a horse.[14]

On the one hand, we may interpret these tales as lauding the exalted love that dares to overstep lines of caste and community. Romantic love here moves beyond the limits prescribed by the social hierarchies. It reverses the dominance of the upper castes over the lower and of the male over the female, much as tales like Laila majnun and Hir ranjha questioned the authority of elders over the young. The legitimacy of romantic love, as these tales' heroes and heroines continuously recite, resides not in its legal sanction or propriety but in its spontaneity, its irrepressibility, its sheer persistence in the face of opposition. The stories with happy endings seem further to suggest that an affair of the heart having illicit beginnings may transform itself into the approved state of marriage, even of intercaste marriage, once the lovers convince the guardians of the bride of their overwhelming commitment to each other (which they usually demonstrate by their willingness to sacrifice themselves and die). These dramas thus illustrate that within the social domain some space remains for deep feeling. They play on the possibilities within that space, keeping alive the attachment to the ideal of romance while mildly debunking the rigidities of caste and class.

On the other hand, the consistent assignment of the female to the dominating position perhaps proceeds from a feudal concept of hierarchy and a notion of courtly love consonant with patriarchal values. The superior status of the beloved, although bestowing on her undoubted power and privilege vis-à-vis society, gives her the potential to oppress her lover. The Nautanki dramas do not particularly stress this configuration; nevertheless, the status differential at least hints at the

haughty beloved found in court-based genres of Indo-Persian literature. The high position of the beloved in that tradition provides a means of representing the degradation and social opprobrium that the true lover gladly undergoes. His suffering is testimony to his constancy and moral fitness for the supreme trial of love. We are reminded of the deplorable condition of Majnun, the important difference being that society's ridicule and his own self-abandonment lead to Majnun's becoming an out-caste, whereas in the Urdu ghazal for example, it is the beloved herself who is usually responsible for the sufferings of the lover, inflicting pain out of cruelty.

In our Nautankis, the princess Shirin comes the closest to this attitude, although eventually she is won over by Farhad's valor and comes to love him equally. The other princesses respond more favorably to their lovers from the start. Even when they assume the aggressive virangana guise, their motivation is to protect a suitor's life; they turn their attacks against society and its authorities, not against the lover. Nonetheless, the high status accorded to these heroines erases the obstacles they face as women in patriarchal society, especially in comparison with tales such as Laila majnun and Hir ranjha . The social reality of being female vanishes from the text, yielding to an artificially elevated ideal of womanhood that aggrandizes the male's self-sacrifice and ignores the female's experience. Furthermore, the high-born beloved motif reinforces the association of superior beauty, power, and merit with high caste or class, providing support for the logic of hierarchical organization, even though the narrative ending of intercaste marriage overrides that hierarchy.

The prototypical love affair between a highly placed female and a beseeching subordinate male is generally thought of as an Islamic legacy, just as the prevalence of unrequited love and the tragic ending are traced to Muslim sensibility and considered anathema to the Hindu mind. Within the body of romantic tales found in the Nautanki literature, however, the tidiness of these distinctions breaks down. Some classic romances like Laila majnun or Shirin farhad that end in both lovers' deaths clearly traveled from the Islamic Middle East to Indo-Pakistan. Others equally tragic (Hir ranjha, Sorath bija ) have roots in the subcontinent and are thought of as the cultural property of a cross-section of communities. Similarly, the high-status beloved is not limited to one particular religious tradition. It is commonly linked to the Sufi mystical allegory, wherein the earthly beloved (mahbub ) is portrayed as lofty and inaccessible because such are the attributes of God, whom the be-

loved symbolizes. Yet the motif occurs in other contexts where a Sufistic interpretation would be inappropriate.

A good example is found in the Alha cycle—a story corpus indigenous to the middle Hindu castes of North India. Incidentally, this well-known non-Islamic narrative ends in tragedy, insofar as most of the heroes are killed in a great battle. Within this larger frame a number of smaller battles take place, and almost all revolve around the marriage-capture of a bride whose family is more highly placed than the Banaphar clan of Rajputs who are the suitors. The Banaphar heroes succeed in each of these encounters but only after enduring abuse and insults and resorting to physical combat. In the Alha legend the high status of the beloved, while calling up the code of chivalry and courtly love, primarily provides a pretext for the Rajput warrior to prove his mettle. Love backed by force triumphs and leads to marriage, reversing the claims of caste distinction.

Intercaste love is a common theme in more recent Nautanki stories as well. No particular rule governs the assignment of lower status to the male or female in these stories. Indeed, low status often seems to be associated with rejection by or loss of a parental figure, a plight that affects children of both sexes. In many of these "modern" tales, the hero's or heroine's misfortune leads to a situation of mistaken identity. A low-caste person volunteers to raise the abandoned child, bestowing his or her caste identity upon it. The leading characters, having become adults, subsequently fall in love across caste lines, but the conclusion typically involves a discovery of the original high caste of the abandoned child, and the finale of marriage thus brings together individuals who in fact socially match each other.

The drama Mali ka beta (The gardener's son) exemplifies these themes and also incorporates a number of aspects of both the Laila-Majnun story and the melodrama plot.

The prince Firoz is born to his royal parents after years of childlessness. The dying king wills his kingdom to his son, placing his minister Afzal on the throne to rule until Firoz attains the age of majority. Afzal, fearing loss of his power, has the prince sent to the forest for execution. There he is rescued by a gardener, who takes the boy home and brings him up as his son.

Soon after, Afzal's daughter Shamsha is born. Independent and indifferent to the idea of marriage, she falls in love with Firoz when he delivers her flowers on her sixteenth birthday. The lovers vow to love each other until death and be remembered like Laila and Majnun. They suffer various persecutions from Tagril, Shamsha's suitor, and Afzal.

When Firoz goes to look for water for the tormented Shamsha, he is stoned by the townspeople. He then proposes to kill himself to give her the blood of his heart (khun-e-jigar[*] ) to drink. Finally Shamsha resolves to die rather than marry Tagril, on condition that she be buried next to Firoz. Firoz's last wish is that he meet his father. The gardener appears, reveals the truth about Firoz's birth, and explains Afzal's role in the deceptive execution plot. The nobles turn against Afzal, place Firoz on the throne, and the lovers are married.[15]

The previous pattern of romance between a high-born female and low-born male, ending in a suspenseful execution scene, becomes even more melodramatic here. The narrowly avoided execution is replicated at the beginning of the story, following a sequence in which the boy heir is first abandoned by his dying father and then betrayed by the power-hungry minister. Within this outline, the pathos of the drama is heightened by numerous references to the Laila-Majnun story: the lovers' vows to be remembered like the immortal pair, the pelting of Firoz by the townspeople, his willingness to sacrifice himself for her well-being, and the couple's resolve to die together and be buried next to each other. The theme of passion in defiance of class differences operates as the foundation, the chief departure from earlier tales being that in the end the status of the lovers turns out to be equal. The lovers' compatibility of rank and the revelation of the minister's treachery, rather than the sheer depth of the lovers' feeling, reverse public opinion and pave the way for their union.

The abandoned daughter, counterpart to the hapless boy Firoz, is the focus of sympathy in Andhi dulhin (The blind bride).[16] Again a much desired child, Pyari, is finally born to a royal couple, but the queen dies soon after, and the grieving daughter weeps herself into blindness. The king is faced with the impossible task of marrying a disabled daughter and abandons her in the forest. Instead of being raised by a low-caste family, the girl in this story takes to begging. The Nautanki proper begins when a certain prince, Jaipal, is forcibly married to Pyari as punishment for disrespecting his father. Through a series of difficult adventures, the couple demonstrate their virtue and constant devotion to each other and are eventually rewarded with the return of Jaipal's father's kingdom and their real identities. Here love prospers despite the unequal stature of the partners and, as in Mali ka beta , the apparently disadvantaged Pyari turns out not only to be worthy but to have high rank. A strong ideal of self-sacrifice emanates from this love story, which

evokes a sufficient measure of pity through the sad circumstances accompanying the child's "handicap."

The fixation on childhood abandonment in these two dramas (and others like them) points to a questioning of social structures and the stability they are supposed to provide for the young. The stories seem to indicate that the social umbrella made up of family, clan, and caste alliances is not always effective in protecting children. The loss of a parent is a threat not only to the physical and psychological health of the boy or girl, but also to the child's social identity; caste affiliation as well as family connections are easily obliterated by the removal of the guardian figure. Together with this sense of insecurity, the stories show the continuing romantic attraction exercised across caste lines. They repeatedly invoke true love as greater than caste, greater than family. In dramas with the mistaken identity motif, however, love leads to a marriage that conforms to caste rules, fulfilling a conservative desire to reproduce the status quo. These stories confirm, too, the larger rationale that credits moral superiority to high birth: the abandoned children manifest the goodness inherent in their superior birth-status, even when that status is unknown to them. A powerful romantic ideal challenging the social order thus engages with a narrative structure that removes the discomfort of that very challenge and eases it into harmonious marriage within conventional bounds.

Relations between Communities: Hindu and Muslim

We consider last three dramas not directly concerned with romantic love that may shed further light on the issues of birth, loyalty, community identity, and intercommunal relations. In this case, we speak not of differences between castes within the Hindu hierarchy or of classes within Muslim society but of the larger gulf that separates Hindus from Muslims. One of these Nautanki plays depicts the enmity between the two great communities as implacable whereas the other two see friendship and trust to be possible, and the two communities aid each other even while respecting the other's separate identity.

The Sangit of Dharmvir haqiqat ray (Haqiqat Ray, defender of the [Hindu] faith) reads almost like a document written to foment communal hatred.[17] The story focuses on a young Hindu Punjabi boy who chooses martyrdom over conversion to Islam. After mastering Sanskrit, the child enrolls in an Islamic school with the intention of learning the

Persian language. (In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Persian was the official language of the court and government affairs; knowledge of Persian was a passport to employment.) He quickly becomes the victim of jibes from the Muslim schoolboys. During a religious debate with them, he compares the gods of Hinduism to the god of Islam; for this blasphemy he is brought before a judge and given an ultimatum: convert or die. Ignoring the advice of family, he chooses death and glorifies the fame of the Hindu religion (dharm ). The drama paints Muslims as intolerant, unjust, and merciless in their demand for the child's death, whereas Haqiqat Ray and his family come across as entirely innocent victims. Perhaps the story originated in a period when Muslims held political control of the Punjab and the difficulties of economic survival for the upper Hindu castes produced religious intolerance and fear.

Against this partial view of communal tensions, two twentieth-century Sangits deliberately espouse the cause of Hindu-Muslim unity. Both dramas take the viewpoint of the majority Hindu community and describe events that befall their Hindu characters. Muslim characters play significant roles and are exemplars of their communities, as if the dramas intend to dissuade Hindus from prejudice against Muslims. Curiously, both stories commence with circumstances reminiscent of Mali ka beta and Andhi dulhin . A child is abandoned by its parents and raised in a household belonging to the other community, but in these cases the child's religious affiliation is preserved. In Shrimati manjari (The valiant Manjari), the Muslim boy Jalal and the Hindu girl Manjari grow up as brother and sister, coming to each other's assistance when trouble strikes.

During an epidemic of the plague a poor Muslim and his wife die, leaving their son, Jalal, an orphan. Seeing the boy starving and ignored by his own community, a Brahmin named Jugal Kishor adopts him. Jugal's wife has also died in the plague, and he has a daughter named Manjari of the same age as Jalal. Jalal is enrolled in an Islamic school and raised as a Muslim.

Some years later Jugal falls ill and is beset by his creditors. Manjari offers to stand as surety for a loan and joins the household of the moneylender Janaki as a maidservant, while Jalal goes out to beg for money to repay the debt. Manjari successfully defends her mistress against a raid by dacoits, earning the title "Shrimati" for her courage. Jalal meets Kamruddin, a merchant, who is impressed by his story of the Brahmin who brought him up, and he gives Jalal the money needed to repay Janaki.

Janaki makes advances to Manjari but is thwarted when Jalal arrives

to hand over the money. Janaki implicates Jalal in an incident in which Jugal is attacked by Janaki's servant and left for dead. When Jalal is sent to jail, Manjari seeks protection from Jalal's friends, Kamruddin and his wife. At Jalal's trial, Jugal shows up in court alive, and Jalal is proven innocent.

Janaki renews his pursuit of Manjari. This time Jalal arrives just in time to save Manjari's honor, and in his rage he stabs Janaki and kills him. Manjari is suitably married off. Jalal's name becomes immortal after his death (presumably he is executed for the murder of Janaki). The play ends saying, "Not all Muslims are alike. What Hindu would have done what Jalal did?"[18]

The kind-hearted Brahmin functions in this story much as the gardener, the potter, or washerman do in other tales that return an abandoned child from the brink of death. The financial difficulties that beset Jugal Kishor accent the altruism of his action; he is an impoverished individual himself, yet he takes on the rearing of another community's child—and that too without a wife. Jalal repays the debt he owes his foster father for his upbringing by seeking funds to pay off Janaki, by going to jail on a false charge, and by risking his life for the sake of Manjari's honor. In these various ways he proves himself a perfect son and brother, demonstrating that Muslims can be grateful, loyal, and courageous. The relationship between Manjari and Kamruddin reinforces the message of mutual assistance across community lines. When she is threatened by a greedy and lustful Hindu merchant, she seeks shelter with her brother's Muslim friends who take her into their home just as her father took in Jalal. This encounter gives a mirrorlike symmetry to the play's events, the Hindu's rescue of a dying Muslim boy at the beginning of the story answered by the Muslims' harboring of a threatened Hindu girl later on.

This drama is silent on the issue of religious differences between the two communities, never probing into the clash of beliefs that led the youth Haqiqat Ray into his precarious position. Simplistic in its analysis of communal tensions, the drama nevertheless proposes a morality that moves beyond religious creeds and dogmas. This morality may be illuminated through the metaphor of moneylending: an act of good performed for another human being creates a moral debt that the other must repay with interest. Communal relations can be substantially improved—the drama seems to assert—when good acts are viewed as emanating not just from the individual but from the community as a whole and hence deserving of return by the other community as a whole. Thus

Kamruddin "repays" the initial kindness of Jugal to Jalal by offering the money and protecting Manjari, although he "owed" the Hindu community nothing on the basis of his own experience. The story itself ends with a moral surplus on Jalal's side—he has done so much good for Jugal and Manjari that surely the Hindus in the audience will extend themselves to act generously toward Muslims in future transactions.

It is significant that the moral guidance provided by this metaphor preserves the integrity and social boundaries of the two communities. Hindus remain Hindus and Muslims Muslims, even when reared in shared households. There is no hint of romance or sexual commerce across community lines, and indeed Jalal remains celibate—almost a renunciant figure—dying before he assumes any sexual identity. Manjari and Jalal have the relationship of brother and sister instead of the romantic tie between hero and heroine. Their attachment to each other is permeated by a level of devotion, loyalty, and affection comparable to the romantic bond between lovers, but their relationship lacks sexual overtones, holds no potential for marriage, and cannot jeopardize the purity of blood lines in either community.

Another popular play with origins in the Bombay cinema, Dhul ka phul (Flower in the dust), likewise explores the theme of a child's abandonment and adoption. In this case it is a Hindu boy, the illegitimate offspring of a middle-class couple who meet in college, who is raised by a Muslim foster father and sheltered against the harsh rebuffs of the world until his natural parents accept him back into their hearts.

Mahesh, the top student in his M.A. class, meets Meena, foremost among the girl students, when their bicycles collide. They fall in love and continue to meet after exams are over. When Mahesh is called home by his father, Meena reveals that she is pregnant. Mahesh promises to speak to his father about their marriage, but once home he is unable to muster his courage and instead agrees to marry another woman, Malti. Meena is forced from her home and gives birth to a son.

Meena goes to Mahesh, who is now a magistrate, asking him to help care for the child. He refuses. Losing hope, she leaves the baby boy in the forest. A Muslim named Abdul discovers the child and tries to find a home for him, but since his religion is unknown, no one is willing to raise him. Abdul himself decides to adopt the child and names him Roshan. He is excommunicated for this act.

At school, Roshan is constantly harassed and taunted for being illegitimate. He begins avoiding school and keeps company with hood-

lums. One day a thief drops a bag of money in front of him and the police arrest him. Abdul enlists the services of the barrister who is now married to Meena, and she realizes the boy is her son. The case is tried with Mahesh acting as magistrate. In court Meena declares that Mahesh is the child's father and the one guilty for his wicked ways. Mahesh repents and expresses willingness to take Roshan home. He asks that Roshan be returned to Meena and himself. After much discussion about who deserves to keep the boy, Abdul hands Roshan over to his mother and leaves for a pilgrimage to Mecca. The play ends with an exhortation: the two communities should live together harmoniously, as the Muslim did with the Hindu child, for the good of the nation.[19]

This story brings our discussion of romantic love and community loyalty full circle, focusing as it does on the outcome of a love affair between students, a Laila-Majnun tale in modern dress. Times have certainly changed. The powerful attraction between the young people is no longer the pak ishq of olden times; it is mutual and ardent, no doubt, but hardly enduring and certainly not frustrated or unfulfilled. For the first time in the narrative universe examined in this chapter, the corporeality of love intrudes in an unmistakable and rather unwelcome way, leaving behind its debris—the illegitimate child—once the love affair is over. Both Mahesh and Meena attempt to distance themselves from this threat to their social status and, abandoning the boy, go on to successful positions in society. He marries and becomes a magistrate, while she gets a job as secretary to another barrister and later becomes his wife.

The moral focus thus shifts rapidly away from the romantic ideal to the themes of parental responsibility and communal cooperation. Abdul Chacha (uncle), another wholly selfless and guileless Muslim like Jalal, manifests the caring and kindheartedness that alone can save Roshan. His generosity contrasts with the narrow-mindedness of other Muslims, who are unwilling to bring up a child from a different community and who excommunicate Abdul for doing so. Although Abdul gives the child a Muslim name, he does not necessarily raise him as a Muslim; the text repeatedly emphasizes that no one knows the religion into which the child was born. Abdul is intent on providing the boy with a good education and making him a respectable member of society. He is enrolled in the same school as Ramesh, the son of Mahesh and Malti.

In spite of the attention and love he receives from Abdul, Roshan

begins to manifest the signs of his troubled background. Shamed for his birth rather than his character, he is driven into the company of rebels and deviants, and his own behavior gradually deteriorates. It is as though the moral lapses of his parents, and his father in particular, are being meted out on him for repayment. His suffering, culminating in the false arrest, seems to proceed not from parental neglect—for Abdul is there— so much as from a kind of curse, a punishment for the irresponsibility of Mahesh and Meena who live comfortably denying their past. Finally the courtroom trial of Roshan forces Mahesh and Meena to examine themselves and begin to atone for the errors of their youth. The sentimental reunion of lost child and guilty parents possesses a moral logic of its own, although Abdul's claim as foster parent seems to wither overnight, and he gets only scant thanks from Meena and Mahesh.

Enclosing both Hindus and Muslims within the impermanent structure of the family of adoption, Shrimati manjari and Dhul ka phul create a pattern for caring intercommunal relationships. In these plays, the paradigm of romantic love shifts to a paradigm of parental and sibling love, defusing the potential for volatile sexual contact between the two communities. The constellation of moral traits associated with the familial caregiver is in many ways the same as the one that defines the true lover: attachment in the face of society's hostility, defiance of conventional norms, extreme loyalty, self-sacrifice to the point of death. The path to communal harmony offers many of the same hazards as the path to union with the beloved and consequently requires the fortitude and self-sacrifice that characterize the lover as well. Despite these challenges, the dramas point to the clear possibility of cooperation and loving interaction. While not going so far as to extend the concept of romantic love to alliances between Hindus and Muslims, the alternative construct of mutual support at the family level brings the communities into an intimate bond, displacing fears and allowing individuals to explore interaction beyond the rigid perception of essential differences in character.

These dramas, like those on intercaste romantic love, echo the perhaps universal intuition that human beings—whatever their differences—share the capacity for deep feeling. Not all individuals are equally capable of experiencing supreme joy and sorrow, not all are qualified for the test of love. But the ability to feel, to love, and to care is not determined at the outset by affiliation with a particular clan, caste, class, or religion. Loving falls within the range of being human. It is as one

human to another that the queen and the stonemason love each other, as one human to another that the Hindu parent fosters the Muslim child. Learning to love is an achievement, a result of striving and endeavor, not a birthright, and therefore it occurs in no greater measure in one caste or creed than another.

The stories analyzed in this chapter definitively prove the case for love, be it the tragic love of the immortal couples, the cross-caste romance of adventuring heroes and high-born heroines, or the familial affection possible between Hindus and Muslims. Love, which most fully stretches and exercises the human heart, is highly valued in the society from which Nautanki springs. Those who engage in its often perilous pursuit are praised, glorified, and celebrated in the tales, songs, and dramas that populate North Indian folklore. So great is the appreciation for this most compelling of human emotions that the tales compare the experience of love to the search for God. Given the lofty position love occupies within the culture, it is evident that the lover is not only a fervently moral individual but one who has superior spiritual insight or competence. In this regard the lover is like a mystical seeker, and the act of love is akin to renunciation.

These formulations bespeak an affirmative response to the life of the heart, to the capacity for deep attachment and feeling, and they construct a space within cultural memory for the preservation of love and the lore of past lovers. An analytical reading of love's history, however, reveals within the selfsame texts the hard wall of opposition erected to hold back this mighty emotional flood. Family honor, female chastity, maintenance of clan and caste lineages, social propriety, surveillance of the young, and other societal priorities repeatedly suppress and restrict love. They often threaten the very survival of the lovers and punish their reckless yearning with the ultimate sentence: death. In other instances, the intense attachment of the pair finds fulfillment in the acceptable form of marriage. The obstacles that society places in the path of love serve to magnify the selfless, difficult nature of the quest for union with the beloved, yet it is obvious that more than a rhetorical function feeds the image of familial and social hostility to romantic love. Even in the more recent dramas, where love appears minus some of its medieval grandeur, the plots contrive a harmonious accord between the lovers and their families, confirming the existing social arrangements. The dramas on Hindu-Muslim relations likewise allow helpful interaction between the communities without danger of religious conflict or sexual

contact. In this fashion, the established order stands in many of these dramas but only after a contest. The Nautanki romances operate as an arena for sorting out the conflicting responses of society to the experience of love, an emotion that poses a profound moral dilemma for North Indian society. Antithetical to many of that society's aims, it emerges over and over to arouse in men and women actions of nobility and self-sacrifice.