III. The Conflicts of Town Life

8. The Problems and Conflicts of Town Life: The Adult World

Survival in this community of strangers (cf. Robertson 1978) hinges on social and economic success. Well-being for migrants in Ambanja is not just a matter of physical health—it involves personal skills and power in relation to the local social, economic, and political orders. The problems migrants encounter also affect kin who may live elsewhere under severe conditions characterized by a scarcity of land, food, animals, or even water. As healers, tromba mediums are specialists who help others cope with the uncertainties and disorder of life. Local systems of healing reveal the nature of affliction and are indicative of local tensions. Clients come to tromba mediums when plagued by problems that fall into three general categories: physical ill health, work and success, and love and romance. The focus of this chapter is on the problems and conflicts faced by adults in Ambanja; the chapter that follows addresses the special problems that are experienced by children (especially adolescent girls).

| • | • | • |

Malagasy Concepts of Healing

Medical pluralism is an essential element of life in Madagascar, where a wide variety of healers and healing practices operate. In Ambanja, the domains of indigenous practices and Western biomedicine cannot be described as distinct or, as Janzen (1978) has argued for Zaire, complementary. Rather, the boundaries between these healing systems fluctuate depending heavily on the skills of the healer, the preferences of the client, and on economic constraints.

Fanafody-Gasy, Fanafody Vazaha

Central to Malagasy notions of healing is fanafody, a term that has multiple meanings. First, it is used to distinguish between different styles of healing: fanafody-gasy or “Malagasy medicine” and fanafody vazaha or “foreign” or “European medicine” (which I will refer to here as “clinical medicine”).[1] In Ambanja, indigenous healers, or those who specialize in fanafody-gasy, include moasy (HP: ombiasy) or herbalists; mpisikidy, the diviners who specialize in the vintana, a complex zodiac system which operates in reference to time and space (see Huntington 1981); and the mediums for tromba, kalanoro, and tsin̂y spirits. Here I will focus on the tromba medium as healer, who in many ways epitomizes the work of these different types of indigenous practitioners.

Ambanja also has a variety of practitioners trained in clinical medicine. Since it is a county seat, the town has a public hospital. In 1987 this was staffed primarily by female nurse-midwives and one male nurse. Usually there are also at least two medical students in residence (stagiaires) working at the hospital as part of their medical rotation. The primary activities carried out at the hospital are first aid, lying-in services, and the vaccination of children. Common ailments are also treated including malaria, gastrointestinal and dermatological problems, and venereal diseases. There are no operating facilities; serious emergencies must be treated in the town of Hell-ville on the nearby island of Nosy Be.

As a result of the presence of the enterprises, there is also a private workers’ clinic next door to the public hospital. This is staffed by a doctor (who is also affiliated with the public hospital) and several nurses. In addition, there are satellite clinics located at each of the enterprises. Each clinic is staffed by a nurse, and the doctor tries to visit once a week (this depends largely on the condition of the roads and how well the clinic’s truck is operating). In addition, the Catholic Mission runs its own small clinic, where a small charge is levied for visits (the public hospital is free). Here there are two doctors and several nurses. Both the workers’ and mission’s clinics have their own pharmacies, but patients at the public hospital must go to local pharmacies to fill their prescriptions. When I left the field in early 1988, the Catholic Mission was in the course of completing the construction of a new hospital with an operating room. Other services include a small leprosy hospital, maintained by the Catholic Mission in a nearby village, and there is at least one doctor who runs a private practice in town.

The term fanafody also means “medicine” and is used to refer to any substance that can bring about a change in an individual’s state of health—be it beneficial or harmful. In this context, fanafody is a term applied to a wide variety of substances. These include pharmaceutical drugs dispensed by clinicians and pharmacists, as well as the rich pharmacopoeia of medicinal plants used by moasy and other indigenous practitioners. Local plants are used in several ways, such as to make infusions, so that the patient can inhale the vapors or drink the liquid as a tea; there are also preparations that can be used in bath water or applied to the body in other ways. Incantations may be said over herbs or objects to instill them with healing powers. Today the efficacy of medicinal herbs indigenous to Madagascar is being studied by biologists and botanists. Near Antananarivo is an institute for testing the medicinal properties of plants. Similarly, several foreign pharmaceutical companies have become interested in the potential curative effects of the flora of Madagascar (see Boiteau 1979; Boiteau and Potier 1976; Cordell and Farnsworth 1976; Debray et al. 1971; Pernet 1964; Plotkin et al. n.d.; Ranaivoarivao 1974). Perhaps the most famous of these is a plant called the Madagascar Periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus), which is used to produce drugs for childhood leukemia (Jolly 1980: 138; 1987: 173).

Although the cost of pharmaceuticals is kept to a minimum by manufacturing and packaging them in Madagascar, they can still be difficult to acquire, because they are expensive by local standards and are sold primarily through privately owned pharmacies. It is not unusual for adoctor to write a prescription for a drug that can not be found locally (or anywhere in the country, for that matter). Doctors also often write prescriptions for small quantities—sometimes less than the amount needed for treatment—to prevent patients from reselling them at a profit. The drugs available at the private clinics are limited, but they tend to be better stocked than the local pharmacies. Malarial drugs, antibiotics, and dermatological creams are prescribed most often, although they may not always be available. Many patients also prefer to buy the more expensive (yet generally unavailable) imported brands, saying they are more effective than those produced domestically. Although a black market exists, Malagasy tend to hoard pharmaceuticals rather than share or resell them, since they are so difficult to acquire. Also, pharmacists as a rule do not dispense drugs without a prescription (for a contrasting view on other regions of the Third World, see Lee et al. 1991; and Silverman, Lee, and Lydecker 1982, 1986; Silverman, Lydecker, and Lee, 1990).

Malagasy distinguish between beneficial and harmful medicine, the latter being especially important within the context of fanafody-gasy or Malagasy medicine. There is fanafody tsara (“good medicine”) and fanafody raty (HP: ratsy; lit. “bad/evil medicine/magic”); sometimes the latter is translated into French by Malagasy speakers as magique or poison. Fanafody tsara is used to cure, while fanafody raty is used to harm one’s adversaries. It is sorcerors and witches (mpamosavy)[2] who use fanafody raty most frequently, although moasy (herbalists) and tromba mediums (like Marivola in the previous chapter) dispense it occasionally as well. The difference here is that the mpamosavy (sorceror or witch) uses fanafody raty for his or her own sake, whereas the healer dispenses it to clients so that their well-being may improve at the expense of someone else’s misfortune.

I wish to stress that each of these categories of good and bad medicine include substances with known medicinal qualities (pharmaceuticals as well as herbal substances that may be curative or poisonous), as well as other (and what are often referred to in the anthropological literature as “magical”) properties that are transferred to them through actions made or words uttered by the healer. For simplicity’s sake (and in order to reflect Malagasy ways of thinking) I will use the blanket term medicine (fanafody) when referring in general to substances that are used to bring about a change in health or well-being. Good medicine (fanafody tsara) refers to those substances taken willingly by a client seeking a cure, and the term bad medicine (fanafody raty) refers to those substances that are used to cause harm to or to influence the behavior or well-being of another person, unbeknownst to the victim. The terms poison and magic will only appear in the text where informants themselves used them. I wish to stress here that these are definitions developed for specific application within a Malagasy context, because more standard definitions, especially of magic (cf. Evans-Pritchard 1937; Frazer 1976 [1911]; Malinowski 1948; also Favret-Saada 1980) do not coincide with Malagasy conceptions of illness. (For more details on Sakalava concepts of sorcery and magic, see Gardenier 1976.)

The presence of clinical medicine in Madagascar has not led to major distinctions being drawn between substances that have a physiological as opposed to a psychological (or magical) effect. The efficacy of both fanafody-gasy (Malagasy medicine) and fanafody vazaha (foreign medicine) is recognized by Malagasy regardless of their level of education, even if they are trained as clinicians. Rather than rejecting fanafody-gasy, Malagasy intelligentsia often struggle to make sense of what they perceive to be conflicting yet coexisting systems of thought. Similarly, non-Malagasy, especially missionaries and clinicians who have lived in Madagascar for a decade or more, are often equally confused and perplexed not only by the persistence of beliefs in fanafody-gasy, but also by what they themselves perceive to be effective and powerful properties.[3]

Tromba mediums and clinicians generally respect each other’s attitudes toward healing. They do not seek to discredit each other’s methods or knowledge, but view them at times as complementary, at others as distinct or as providing different solutions to the same sorts of problems. The point of view involved changes with each situation. As will be shown in chapter 10, the rejection of explanations associated with fanafody-gasy is a stance taken only by extremists such as Protestant exorcists (and, as I have argued elsewhere, psychiatrists; see Sharp, in press). This is not to say that specialization does not occur. For example, it is only through clinicians that Malagasy have access to many pharmaceuticals, since strict laws prohibit their sale by nonregistered persons. On the other hand, clinicians in Ambanja never repair broken bones, because the bonesetters of the rural north are famous throughout the island for their skills in fixing even the worst compound fractures. In addition, some tromba mediums are skilled diviners who specialize in sikidy divination, using seeds, stones, or playing cards.

Indigenous[4] healers specialize in other problems as well. Those associated with possession are generally considered the exclusive domain of tromba mediums. For example, possession by njarinintsy spirits is a common affliction of adolescent girls, but few clinicians in Ambanja have heard of this disorder unless they grew up in the north, and even they rarely see it since it is spirit mediums and other healers who specialize in treating it. Clients may go to the clinic complaining of headaches and stiffness, but this usually occurs before they have been alerted to the possibility that a spirit might be making them ill. If there are any rules directing a hierarchy of resort (Romanucci-Ross 1977), they are very loosely defined. Roughly speaking, they are as follows: if someone feels physically ill in a way that is unfamiliar, he or she usually goes to the clinic first to receive a vaccination or a prescription, usually for antibiotics. If the treatment is unsuccessful (or prohibitively expensive) they will try other means. Sakalava are an exception to this rule. They prefer to consult moasy and tromba mediums over clinicians. Sakalava say this is because they are wary of being treated by Merina doctors.

Clearly, Ambanja’s inhabitants have a wide variety of healers to consult. None, however, is so widespread and so numerous as are tromba mediums. Choices made regarding treatment and more general assistance are very personal. These depend on individuals’ past experiences, their faith in (or, as noted earlier, their sentimental ties to) a given healer (or spirit), and the cost of their services, rather than simply the nature of the problem. The proliferation and professionalization of tromba mediums and other indigenous healers is, I believe, evidence of the limitations of clinical medicine in Madagascar. This includes its inability to solve problems that extend beyond physical ailments into the social realm (cf. Janzen 1978); the severe shortage of drugs and medical supplies needed to guarantee quality care; and, finally, Sakalava reluctance to consult with clinicians who are from the high plateaux.

In Ambanja, healers—be they moasy, tromba mediums, or clinicians—are thought to be skilled if they are able to cure problems that extend beyond physical ailments. Well-being is defined in broad terms and extends into the social and economic realms of human experience. Tromba mediums are especially adept at this. They serve as gatekeepers between the world of the living and the dead, and between the present and the past. When they reach the boundaries of their knowledge, they may refer to other ancestors of the spirit world for guidance and advice to assist the ailing client.[5] As ancestors it is their duty to watch over the living. They have not only a keen awareness of what comes to pass in the local community, but also the power to bring about change.

A medium’s knowledge overlaps with that of clinicians: they can treat, for example, infections, malaria, sore eyes, and diarrhea. Throughout the past decade, Madagascar has become a country of scarcity, as is evident by the bare shelves in the country’s pharmacies and public hospitals. In Ambanja, patients who require surgery must purchase their own gauze, bandages, and anesthesia, and then go elsewhere to have the operation performed. Often the required materials are unavailable locally, and people with serious emergencies may die before they can reach Nosy Be. The workers’ and Mission’s clinics are better stocked than public pharmacies. Still, sometimes as much as half of what has been ordered (and paid for) may be missing from the packages. This is what Malagasy refer to as risoriso, or corruption (HP, lit. “to zig-zag,” “wander,” or “weave in and out”), and it is very much a part of everyday life. Unlike clinicians, tromba mediums rely on local sources of ancestral power and knowledge, and they draw from an extensive and readily available pharmacopoeia of local plants.[6] Tromba mediums also rely on the power and sacred knowledge of royal ancestors.

Healers in Ambanja are problem solvers and not just curers. Because of the authority and stature that accompanies their knowledge and abilities they are often asked to assist in a variety of crisis situations. They give loans and advice, and they are frequently called upon to mediate in personal disputes among kin, between employees and employers, and between private citizens and local public authorities. They may be elected to serve on neighborhood committees, where one of their main duties is to hear local disputes. In this way, their social duties may overlap with those of enterprise directors, elected political officials, judges, and the Bemazava king. The town’s judge reports that sometimes tromba spirits possess their mediums and appear in court to defend or threaten a party or order him to make a particular decision.

| • | • | • |

Sickness and Death

Ny aretina dia toy ny akoho: mahita làlana hidirana nefa tsy mahita làlana hivoahana: lit. “Sickness is like a chicken: it can find the way in but it can not find the way out,” that is, sickness comes easily; it’s getting well that is difficult.

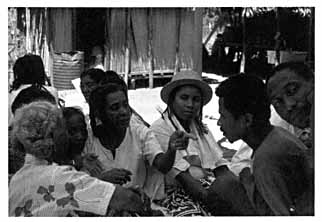

Sickness and death are times when tromba mediums play crucial roles in the lives of their clients. In Ambanja, the concern for one’s well-being is reflected in the greetings people use: “Mbola tsara?” (“[are you] still well?”) and “Salama, Salam-tsara” (“[ go] in good health”). Since many of this town’s inhabitants are wage laborers, economic stability hinges on good health. Sickness may interfere with productivity or it may threaten an individual’s ability to hold on to a job. Given this, it is not surprising that many of a tromba medium’s clients are vahiny laborers (see plate 7).

Tromba mediums assist clients who suffer from a variety of ailments. Among the most common are sore eyes, stomachaches, bad headaches, and stiffness in the limbs, back, or neck. Mediums such as Marie, for example, possess an extensive knowledge of the local pharmacopoeia. When Marie is in trance her tromba spirit often instructs her clients to use certain medicinal plants. If these are unavailable, the spirit tells Monique, the rangahy, to go to the forest nearby to retrieve them, or the spirit might write a prescription so that the client can purchase the herbs from a moasy. Sometimes the client goes home to administer the treatment or returns later to have the tromba spirit do it (or so that the spirit can give further instructions). For most of these private consultations Marie’s clients are young adults in their twenties and thirties. Marie also participates on a regular basis at ceremonies for other mediums. When she is in trance she is often asked to treat infants and young children who suffer from such problems as fever, chills, diarrhea, eye infections, or crankiness.

7. Tromba spirit giving advice to a client. Since mediums embody ancestral power when they are possessed by tromba spirits, they are regarded as powerful healers. A client may make an appointment for a private consultation, or passersby may drop in unannounced at a large-scale ceremony. Occasionally tromba spirits also give unsolicited advice: this man is being scolded for being drunk in public in the middle of the day.

Death is especially frightening for migrants who are away from home, because to be far from the ancestral land means risking being separated and lost from one’s primary kin. As explained in chapter 4, some migrants have established burial societies in Ambanja. These societies ensure that the dead will be transported safely back home so that they may rest with their ancestors. Again, tromba mediums may be important actors in this context. They may be called upon to help the living understand the causes leading up to the death of a loved one, or they may even fall suspect themselves.

In Ambanja, a clinical diagnosis generally is not sufficient to explain a sudden death. In a manner reminiscent of Evans-Pritchard’s Azande (1937), one must determine the underlying causes: why this person at this particular time? Generally, it is one’s neighbors who are suspected of being sorcerors of witches (mpamosavy) or having used bad medicine (fanafody raty) against the victim. Most often old women fall suspect because they remain at home throughout the day. If they care for their own grandchildren they also develop intimate ties with their neighbors’ children, coddling and scolding them and offering them snacks while they prepare their own meals. Old women are most frequently blamed, ostracized, and shamed as witches following the death of a neighbor’s child, accused of having killed the child with fanafody raty because they are jealous of another’s prosperity. These older women are quite vulnerable, since they often live only with their grandchildren, without any adult kin nearby to protect them.

Witchcraft Accusations against Old Mama Rose

In one neighborhood where I lived temporarily, a two-year-old child died. Although two doctors in town agreed malaria had been the cause of death, the mother, Alice, who was a nurse herself, sought out a moasy and later a tromba medium to discover the identity of the person who had brought death upon her child. For this mother, the medical prognosis was not enough—the child may have died of malaria, but she needed to know why this had happened so suddenly and at that time and place. Mama Rose, an older woman who lived next door, was identified by both healers as a witch (mpamosavy). Mama Rose’s daughter, fearing for her mother’s well-being and safety, took a leave of absence from her own job in a distant town to watch over her elderly mother and to make sure no harm came to her. She also called up Mama Rose’s own tromba spirit to ask for advice and protection from the fanafody raty that they assumed Alice was now using to harm her. Mama Rose was an older woman in her sixties, and so this in itself was a sign of their desperation, for she had not been active as a medium for nearly ten years. After approximately six months the animosity between Mama Rose and her neighbors subsided but only after Alice had moved out of her house, leaving her husband and his child by a former marriage behind. Three months later Mama Rose’s daughter finally returned to work at her job full-time. She continued to visit her mother every weekend until Alice moved away.

This story reveals the value—and the power—of tromba spirits and their mediums. As Alice seeks to make sense of a tragedy in her own life, it is a moasy and later a tromba medium who give her answers that extend beyond those that her own medical training can provide. Mama Rose, as an old woman who lives alone, is a vulnerable target and she, in turn, relies on her own tromba spirit for comfort and support in time of crisis. As the stories that follow reveal, tromba spirits and their mediums provide a host of other services to clients who struggle with the problems of daily urban life and plantation work.

| • | • | • |

Work and Success

Ny asa no harena: “Work is wealth.”

Work or, more specifically, wage labor, is central to the lives of the majority of Ambanja’s inhabitants. It is Sakalava who are most resistant to working at the enterprises, whereas vahiny, out of necessity, hold the majority of these jobs. As described earlier, most workers express the desire to be freed from the constraints of plantation labor. For many, however, these jobs are a matter of survival. Since employment activities occupy a large proportion of daily life for the majority of Ambanja’s inhabitants, well-being at the job is essential. Tromba spirits answer clients’ needs by providing work medicine (ody asa). Clients request this, for example, to encourage their bosses to grant them raises or to change the disposition of an unkind supervisor or employer.

Doné and His Troubles at Work

Doné is a forty-one-year-old Antaisaka man from southeastern Madagascar. He came north ten years ago, having been encouraged to do so by an older brother, who had been living in Ambilobe for three years. Shortly after Doné’s arrival, his brother left, and Doné decided to move to Ambanja because he had heard that it was easier to find work there. Since he knew how to drive a car, he soon found a job as a truck driver at one of the larger concessions.

After working there for four years, Doné saved up enough money to pay to have his wife come join him. She brought with her their first child, who was five years old at the time. They have since had four other children. Doné and his family live in a two-room house made of corregated tin and located on land owned by his employer. They also have access to a small field where his wife grows such subsistence crops as manioc and garden vegetables. Doné finds it harder each year to earn enough to support his family. He says that they do not starve, but now he rarely has enough cash to buy clothing for his children. (As long as parents can not afford to buy clothing for their children they are reluctant to let them attend school.)

In 1986, two of Doné’s sons were caught stealing cocoa pods from his boss’s fields. Although workers and passersby are permitted to take one or two pods (which one can break open, eating the seeds as a snack), these boys were found with a gunny sack filled with nearly twenty pods, which ostensibly they were preparing to sell. The foreman who found them brought them to the boss, who took them to the local jail to be fined. As Doné reported, “I did not have the cash to pay the fine, and so I went to my boss and asked him to drop the charges. Instead, he offered to help bribe the judge, but only if I promised to pay him 50,000 fmg up front” (this amount was ten times the fine). Doné felt paralyzed: “I didn’t have the money to pay either the fine or the bribe.…I was so afraid, I thought I’d lose my job. A friend [coworker] later lent me the money…then I consulted a tromba spirit and asked for medicines to help me [counteract the boss’s cruelty].…”

“I told my story to the tromba. He told me to go collect certain types of herbs and bring these with a package of cigarettes and a small bottle of rum. I went back a second time and the spirit prepared the medicine: he blew smoke and sprinkled rum on it, and then he tied it in a small bundle. He then told me to place the bundle inside my boss’s car one night, under the driver’s seat.”

This was not difficult for Doné to do, since he was often in the garage tending to the cars and trucks that were kept there. “A week later my boss found the bundle, and he became very frightened. He was sure that one of his workers was trying to poison him.…For the next month he rarely left his house and only allowed his wife or daughter to prepare his meals, even though he had several house servants! Ha ha! Later he gave all of us a small raise!” Doné felt he had triumphed. When he received his next paycheck, he used part of it to buy a bottle of beer, which he brought to the medium’s house as payment for the spirit’s services.

Doné’s story is important because it illustrates several key issues. First, work is essential to the well-being of migrants, and their survival may depend on the actions of their employers. Second, in times of crisis a tromba medium, drawing upon local Sakalava ancestral power, may solve their clients’ problems. Doné’s case is not one involving impotent medicines, because Malagasy believe in the harmful effects of fanafody and the power of tromba spirits. The bundle under the car seat was an apt warning for the boss, and it proved to be very effective. Third, tromba mediums are not marginal members of this community, but essential and powerful figures who cure personal and social ills. In Doné’s case the tromba medium aided the powerless and vulnerable laborer who was caught in a very sticky web of power relations with his boss.

Status, Success, and Power

In Ambanja, one can gain wealth by “working hard” (miasa mafy) and through various forms of medicines (fanafody). For the powerful, money can influence the outcome of decisions in the local court, and it brings influence in government. For the powerless, it is fanafody that can bring about change or relief from the hardships of everyday life. A brief example illustrates this point. In one neighborhood a very wealthy merchant was in the process of constructing a large building (he had acquired the land by bulldozing other people’s houses one afternoon while the police stood by and watched). He was forced to bring this construction to a halt after a local, self-acclaimed sorceror (moasy) declared in public that he had mustered all his powers to harm the merchant and his family, and he would continue to do so as long as the construction continued. The merchant met in private with the sorceror and paid him a generous sum of money to stop his actions and to keep quiet. The construction then resumed.

An important aspect of fanafody is that the client may use it to increase his or her status, success, or power relative to that of others. As in the case involving Fatima, below, acquiring this type of assistance may require a series of intense negotiations. Her relationship with Marivola was a complex one, where a long-term, reciprocal association cemented their friendship. Marivola is a master of this sort of negotiation. Since she dispenses harmful medicines, her relationship with a client must not only be one based on trust, but also one where the client remains in debt both to her spirit(s) and to her (see, again, the discussion of Marivola in chapter 7). Fictive kinship provides a means for redefining these relationships so that such negotiations are possible (and more binding).

The Case of Fatima

Fatima and Marivola were not always friends. Mme Fatima’s neighbors were amazed to see the two women visiting with each other during my stay in Ambanja, for only the year before the two had had a serious quarrel following the death of Medar, Fatima’s husband. Fatima, however, decided to make amends with Marivola, because she knew that she was a powerful medium who could help her to achieve certain goals.

Medar had been a talented and respected school principal in Ambanja. He also had a fair amount of money, which he had inherited from his father. He had died suddenly at the age of forty-two, and doctors in town were unable to identify the cause of his death. Fatima was grief stricken and was certain that her friend Marivola was responsible. She assumed that Marivola was jealous of their prestige and wealth (and she was right—Marivola was jealous). Fatima’s family lived in great comfort in a well-furnished, five-room cement house. They had such expensive luxury items as a color television,a VCR, an Italian-made sewing machine, and a gas stove. Furthermore, Marivola had the skills to enable her to cause such harm, for she was a powerful tromba medium who specialized in fanafody raty. During Medar’s funeral and for months after Fatima made it clear to her neighbors that she believed Marivola was responsible, and all contact broke off between the two women.

But Fatima is an ambitious woman: she has six children, all of whom are enrolled in the private Catholic Mission school. In 1987 she sent her oldest son to complete his last two years of schooling at the private and very prestigious French school in the provincial capital, hoping that there he would have a better chance of passing the baccalauréat exam, thus enabling him to continue on to university and thereafter get a good job. Meanwhile, she was having trouble controlling her fifteen-year-old daughter, who, being very beautiful and coquettish, had had a string of lovers, including some of the most powerful men in town. Fatima felt it necessary to take action to protect her children. For her son she wanted fanafody to help him with his studies; for her daughter she wanted, first, to prevent other women from harming her out of anger or jealousy and, second, she wanted to control her actions and felt that a good scolding from a powerful tromba spirit might accomplish this. Because Fatima was aware of Marivola’s power as a medium, she reopened communications with Marivola, visiting her on a regular basis over the course of two months. Marivola herself had much to gain from her friend. Since Fatima worked as a nurse at one of the enterprises, she could write prescriptions for drugs, and since she was well-off financially, Marivola could request loans from her friend when she was in need. Marivola eventually consented to provide the fanafody, and over the course of two months, the women met regularly to call up Marivola’s most powerful spirits. Fatima paid dearly for these services, giving a total sum of 20,000 fmg to Marivola’s spirits. I also watched her help Marivola acquire drugs and injections on four separate occasions.

In Madagascar, a country of economic extremes, an individual’s success and power draw attention and suspicion from others (cf. Favret-Saada 1980). This is illustrated by a body of folklore that was popular a decade or two ago surrounding French ex-patriots. These stories are rich in imagery that describe Europeans who live off the bodies of the less fortunate. Europeans were suspected of being “blood thieves” (mpaka-raha) and heart snatchers (mpakafo). More recently, Indian merchants have become scapegoats in times of greatest national scarcity. Occasionally, violent outbursts occur throughout the island, directed against Indians. This violence is precipitated by the spreading of an apocryphal story in which an Indian merchant kills the child of a Malagasy beggar (katramy), striking it after it has touched a morsel of food in his shop. Such a story circulated in Madagascar in 1987, and angry Malagasy destroyed Indian-owned shops throughout the island.[7]

| • | • | • |

Love and Money, Wives and Mistresses[8]

Tsarabe ny manambady: “Marriage is wonderful.”

As outlined in chapter 4, marriage ceremonies are infrequent and relationships more generally are extremely fragile in Ambanja. By the time most adults have reached their forties, they have been involved in a series of unions, each of which has lasted only a few years. The tenuousness of relationships today is reflected in the fact that many tromba mediums and other spiritual practitioners do a lucrative traffic in love medicines (ody fitia) for both men and women, who hope either to hold onto a wandering partner, to cause harm to a rival, or to charm a potential mate.

Any man with money in his pocket—be he married or single—is a target for seduction. In precolonial times, polygyny was a sign of success and power for Sakalava men (particularly if they were royalty). More recently this has changed in response to the effects of colonialism. The French colonial period was marked by the transition from a subsistence economy to one characterized by wage labor, with status being measured by possessions and monetary wealth. The co-wife has slowly been replaced by the mistress, who today is ironically referred to as the deuxième bureau (lit. “second office”). This name conjures up images of excessive work, referring to the fact that a man has to work harder if he has a mistress. From a wife’s point of view, it is also a reference to sabotage,[9] since the mistress is viewed as an enemy to the stability of the man’s marriage and household. This new term has become popular within the last decade. Previously the term used was bodofotsy (“bedcover” or “blanket”), since a man’s mistress (like his blanket) is someone he takes with him when he goes traveling (en tourné).[10]

Women who have children and who are involved in tenuous unions are particularly vulnerable economically. A woman who relies on a man for income to support her and her children may suffer greatly if she does not have another way in which to generate an income—a job, a small business, or the ownership of land. Although neighbors often help one another with short-term child care or cooperate in economic ventures, a premium is still placed on kinship. Thus, if a woman is a migrant without extended kin living in the area, her problems become even more severe. Fostering is still a common pattern throughout Madagascar (see, for example, Kottak 1980: 185 on the Betsileo, and Bloch 1971: 9 on the Merina). A common pattern in other parts of Sakalava territory is that children of divorced parents typically go to live with their fathers (Feeley-Harnik 1991b: 218).[11] In Ambanja, however, an additional pattern has emerged: the female-headed household. Children are often left under the care of the maternal grandmother (as in the case of Mama Rose, above), while the mother lives elsewhere, working to support not only herself and her children, but her aging mother as well.

Love and money are very important themes in Ambanja society and are subjects that appear with great frequency in the form of popular sayings. These are often printed on the colorful lambahoany cloths that local women wear as body and head wraps and include such phrases as:

I know of only two crimes that inspire public outrage and mob violence against the perpetrator in Ambanja society: taking property from someone, or sleeping with another person’s partner. With the cry of either mpangalatra! (“thief!”) or vamba! (“adulterer!”), neighbors within earshot will drop what they are doing and come running. If they should catch the guilty party or parties, the mob will beat them with their fists or with broomsticks or other hard objects.[12]“I [may] love you [a man addressing his mistress] but I’m not exchanging the-one-in-the house,” that is, the legitimate wife (Tiako anao fa tsy atakaloko ny an-trano);

“I love my spouse” (Tiako vady);

“The big spouse [real wife as opposed to mistress] is the best” (Vadibe tsara);

“I’m so happy to see you, my Darling!” ’ (Falyfaly mahita anao Cheri ê!); and

“Can’t buy me love” [lit. “You don’t need money to have my love”] (Tsy mila vola ny fitiavako anao).

Tromba mediums and their rangahy report that a majority of their clients come seeking love medicines (ody fitia), of which there are two kinds: that used by men to charm women (ody manan̂gy) and that used by women to charm men (ody lehilahy). The first tromba consultation I witnessed early in my fieldwork involved a male client who sought to charm his wife, who had become the deuxième bureau of a richer man. This ceremony was the client’s second consultation. He had chosen to speak with Djao Kondry since this spirit is a young playboy who is knowledgeable about women, love, and romance. After recounting his problem to Djao Kondry, the client unrolled a cloth in which he had a packet of cigarettes, which he gave to the spirit as a gift. Then he withdrew a bottle of honey, some cologne, a packet of medicinal powder, and three bundles of dried leaves. The tromba poured honey and cologne on the powder and herbs, and, after saying a series of prayers, he instructed the man to put a bit in his wife’s food, her bath water, and in their bed. Then she would not be able to resist him, and she would stop going to see her lover.

Migrants who are far from home are especially vulnerable when involved in tenuous unions, as the following case illustrates.

The Story of Lalao

Lalao is a thirty-five-year-old Merina woman who came to Ambanja with her husband, Christôphe (who is Betsileo), approximately eight months ago. Previously they had been living in Nosy Be, where they met. Lalao did not work. Christôphe was an engineer at one of the enterprises and was transferred to Ambanja from the headquarters at Nosy Be. Christôphe has three children(ages five, ten and fifteen) by a former marriage. His first wife was Sakalava; about four years ago she died. Lalao, who had previously been his mistress, then moved into Christôphe’s house and assumed the role as the youngest child’s mother (she is addressed by her neighbor’s by the teknonym “Maman’i’Hervé” or “Mother of Hervé”), having claimed this role during the recent circumcision of this child. Until the night of this story many women in the neighborhood had no idea Lalao was not the biological mother of all three children.

One night when I was visiting with a Betsileo neighbor named Vero, Lalao appeared at the door, sobbing uncontrollably. She told us that her husband had beaten her and that she was afraid to go back to her house. She wanted to go home to her mother in Antananarivo, but she did not have any money of her own, since her husband was in charge of household finances. Vero was at a loss what to do—she did not know this woman well and, like Lalao, she did not have free access to household funds. She decided to go across the road to Isabelle’s house and ask for assistance, since Isabelle worked with Christôphe and thus knew the family better than she.

We assembled at Isabelle’s house and listened to Lalao tell her story in more detail. She had learned that Christôphe now had a mistress here in Ambanja. This new mistress was an older Sakalava woman(ten years his senior). Lalao said that she had consulted a tromba medium last week, asking the spirit to give her two kinds of love medicine: one she put in her bath water (fankamamy oditra, lit. “makes the skin sweet”) so that her husband would want her again. The spirit also gave her her some herbs to sprinkle in their bed, but they did not seem to have had any effect. Since her husband’s mistress was well known in the neighborhood as a tromba medium, Lalao was certain that the mistress had used more powerful medicine to make Christôphe come home and beat her instead.

When Lalao spoke of her economic dependence on her husband and his violent behavior, the other two women(and, ultimately, I, too) began to cry. We looked over her possessions and decided that she should keep her sewing machine, so that she would have a means of support. Isabelle and I then gave her some money in exchange for some of her kitchenware. Vero did the same, taking money from her husband’s till, thus giving Lalao a large proportion of their household savings (close to half a month’s worth of her husband’s wages). Isabelle then went to find Lalao’s uncle (FaBr) to ask for assistance, but he threw her out of his house. Isabelle then appealed to Christôphe, who gave her enough money for Lalao’s transportation back to Antananarivo. Lalao cried late into the night and at one point tried to poison herself by attempting to drink kerosene. Later, when she had calmed down, she fell asleep for a few hours at Vero’s house. This was done against Vero’s husband’s wishes, for he was already furious that his wife had given her so much money. Lalao left the next morning in a transport bound for the capital.

The seriousness of Lalao’s situation was evident in the other women’s reponses. Among Malagasy, in times of crisis—such as sickness or death—self-composure is essential. Except for very close female kin, one never cries at these times. I myself was scolded severely on two occasions for crying, once during an interaction with an angry spirit and the other while attending a child’s funeral. This episode involving Lalao was the first (and only) time I ever saw anyone cry, aside from a mother grieving over a child’s death. The women present not only felt great sorrow for Lalao, but they were also graphically reminded of problems they themselves had suffered. As Vero put it, “I am so sad [mampalahelo] because she is a woman and I am a woman.” Isabelle herself had suffered greatly several years ago when she learned that her husband had a mistress. This she deduced one day when she discovered that their cassette player was missing. At first she assumed that a thief had taken it, but later she realized that her husband had sold it to buy gifts for another woman. Her husband is Sakalava royalty (ampanjaka) from Ambanja, while she is Antakarana (and a commoner) from the north, and so she feels powerless to control his actions.

The following day Vero explained that she, too, had left her husband temporarily following the birth of their youngest child. An important institution associated with marriage in the high plateaux, among Merina and Betsileo, is misintaka: when a woman is unhappy with her husband she may leave him and go home to her parents. There she stays and is watched over by them. When this happens it is regarded as a separation but not a divorce (misao-bady). If the husband wants his wife to return he must approach her parents, bearing expensive gifts. The comparable institution among Sakalava is called miombiky, in which payments are made in cattle (omby). Whereas marriage ceremonies (and misintaka) occur frequently in the high plateaux, as one Sakalava informant put it, “only savage Sakalava living in the bush practice miombiky anymore.”

Although Lalao and her husband are from the highlands, both were migrants who lived far from parents and other kin. In addition, their behavior reflects an adaptation of Sakalava customs, rather than any strict adherence to Merina or Betsileo ones. Where there is no marriage ceremony, as is true for the majority of unions in Ambanja today, there is no reparation for temporary separation. According to Merina and Betsileo custom, if a couple lives far from home, the husband, who usually controls the household finances, is obligated to give his wife money to return to her parents, if she so desires. Thus, the other women viewed Christôphe’s reluctance to help Lalao as a serious breach of custom. When they pressured him, he relented and gave Isabelle some money for Lalao’s carfare home. Lalao, like many women who are unemployed (typically they are married to professional men), relied on her husband for economic support. Since, as a migrant, she was unable to find kin nearby who would help her, she turned to her female neighbors, all of whom were migrants.

Neighbor’s attitudes toward Lalao changed after she had left town:

At first, these women, and others living around her house, refused to associate with Christôphe, and they stopped buying yogurt from his brother (dairy products are hard to come by and are greatly coveted in Ambanja). Two days after Lalao left, her husband’s mistress moved into the house, enabling Christôphe to return to work, since she stayed at home to care for his youngest child. Soon neighborhood opinion changed in favor of Christôphe. A week later Vero’s husband returned from a trip to Antananarivo and told how Lalao had appeared at his parents’ house after her own parents had thrown her out on the street. He went to speak to Christôphe to learn his side of the story and was told that although Lalao appeared very upset, in fact she was the one to blame. She had squandered all of his money, insisting that it be used to buy her beautiful dresses instead of food for the children. Two months later Lalao returned to Ambanja, and tried to form a reconciliation with her husband, but he threw her out under the watchful (and approving) eye of his neighbors. She left town that afternoon.

In all of these stories, involving Mama Rose, Doné, Fatima, and Lalao, tromba mediums provide clients with a means for confronting and articulating problems they encounter in the everyday world. Through this indigenous Sakalava institution, troubled individuals appeal to the power and knowledge of local ancestors in order to make sense of and control their lives in times of chaos. It is through tromba that the living are able to cure life’s ills and uncertainties. These include sickness and death, work and success, and love and romance. Although clients usually specify these particular categories as they define their needs, the case studies provided here illustrate that these categories often overlap. As the following chapter illustrates, children, too, must cope with these and related problems.

Notes

1. There has been much debate in medical anthropology over the construction of an appropriate label for what is generally referred to as “Western bio-medicine” (or some variant of this). Part of the problem is the propensity among many anthropologists to want to oppose things Western to all other systems. I find the label “bio-medicine” to be inadequate, since it emphasizes a biological model. It also implies that indigenous medicine cannot fit into this paradigm, although the biomedical properties of many local medicinal plants are now well known in such countries as Madagascar and the People’s Republic of China, for example. Although I prefer the term “cosmopolitan” (see Dunn 1976), it, too, is problematic, since some assume that cosmopolitan implies urban (Dunn, however, does not intend it to be used in this way). Even though Malagasy use the terms “Malagasy” and “foreign” to distinguish the two, “foreign” is misleading, since it does not include practices that show influence from Arabs, Indians, Comoreans, and so forth. “Clinical” is a more appropriate label in Madagascar since it is the setting—the clinic—which provides the most distinguishing characteristic between “Western” and “traditional” or what I prefer to call “indigenous” Malagasy forms of healing.

2. One person’s healer might be said to be another’s sorceror, but as the story of the merchant’s construction project shows (see below), there are self-professed sorcerors living in Ambanja.

3. My purpose here is to emphasize the pervasiveness of beliefs, not to prove or disprove the efficacy of treatments. Much has already been written on the power of belief in the context of magic and healing more generally. For different perspectives on this subject see Cannon (1942); Favret-Saada (1980); Lévi-Strauss (1963a, 1963b); Hahn and Kleinman (1983); and Moerman (1983).

4. In this discussion of medicine and healing practices I have chosen to use the term indigenous rather than traditional since the latter implies a static form from the past that never changes. Indigenous is also a problematic term, yet here it provides a satisfactory shorthand manner in which to distinguish Malagasy-derived healing practices from those that at least originally were of Western origin. In other words, I am relying on this term as a way to distinguish the differences between fomba/fanafody-gasy (tromba, moasy, mpiskidy) and fomba/fanafody-vazaha (clinical medicine).

5. Although I have never attended a kalanoro ceremony, my understanding is that they, too, consult other spirits, including tromba. Informants report that these consultations are suspenseful—and even comical—since the kalanoro sometimes departs suddenly, asking its audience to wait while it goes to find out the details of the problem. Its return is sudden and surprising, the spirit’s squeeky voice breaking the silence to inform the audience what it has just learned or seen elsewhere by speaking with ancestors or other spiritual parties.

6. The local pharmacopoeia has caught the attention of at least one local clinician, see Raherisoanjato (1985).

7. I heard versions of this story in Antananarivo, Nosy Be, Ambilobe, Diégo, and Ambanja. Interestingly, no violence occurred in Ambanja, although there were outbursts in neighboring towns. The same series of events have occurred at least twice in the last fifteen years in Madagascar.

8. Portions of this section have appeared elsewhere in a different context; see Sharp (1990).

9. The term deuxième bureau was coined by the French during World War II to refer to that branch of the military which was responsible for espionage activities.

10. Feeley-Harnik also notes that Bodofotsy is a common woman’s name in the high plateaux (personal communication).

11. For a discussion of how Vezo fathers ritually claim their children, see Astuti (1991, especially chaps. 5 and 6).

12. This account, as well as the discussion of njarinintsy that follows in chapter 9, may lead the reader to believe that violence occurs frequently in this community. On the contrary, Malagasy are quite reserved, and violence—particularly in public—is very unusual. As a result, such behavior is thrown into high relief because it is such an extreme divergence from the norm.

9. The Social World of Children

Children are often invisible in migration and urban studies. Much of the literature assumes that children do not live on their own, but under the care and watchful eye of adults, who may be kin, foster kin, or neighbors. As a result, their experiences are shadowed by those of their caretakers. When children appear as a discrete category in studies of African societies, most often the themes that frame their activities are economics and health. Schildkrout (1981), for example, describes the manner in which urban Hausa children assist their mothers who are confined, through purdah, to their homes. Others focus on the more insidious qualities of the institutionalization of child labor cross-culturally (Mendelievich, ed. 1979; Minge 1986). Studies in maternal and child health demonstrates that the young are the most vulnerable in times of scarcity (UNICEF-UK 1988; see also Scheper-Hughes 1987, 1992, and other essays in Scheper-Hughes, ed. 1987). Throughout the Third World, children are portrayed as passive victims of poverty whose parents (or other kin) struggle to care for them against a myriad of obstacles. Among the most vivid portraits of the effects of urban squalor on children in Africa are those found in fictional accounts drawn from authors’ firsthand experiences (see, for example, Emecheta 1979). Other studies by Mead (1939, 1961 [1928]) and, more recently, those falling under the direction and editorship of J. and B. Whiting, explore the meaning of adolescence cross-culturally, or, more generally, the experiences associated with growing up in different societies (Burbank 1988; Condon 1987; Davis and Davis 1989; Hollos and Leis 1989; see also the annotated bibliographies of Gottlieb et al. 1966). Only a few studies have explored situations where urban children live alone and care for themselves, but these focus on the extreme margins of life, where children are the victims of abandonment, famine, warfare, or the untimely deaths of kin (see, for example, Ennew and Milne 1990; Reynolds and Burman, eds. 1986; UNICEF 1987).

Northern Madagascar provides a striking contrast. Village children who have successfully completed their studies in rural primary schools and who show promise for more advanced learning sometimes come to Ambanja voluntarily (and with their parents’ encouragement) to continue their schooling (for a similar case from Melanesia see Pomponio 1992). They are, essentially, young migrants: since there are no dormitory facilities available, they live in town without adult supervision. Many children, as young as thirteen, live alone or share a very simple one- or two-room house with a group of other students. These children must cope, on their own, with the complexities of two realms of experience. First, they must be able to make the shift from rural to town life. Second, they must face the problems that characterize the transition from youth to adulthood. Typically, they are the children of Sakalava tera-tany or non-Sakalava settlers who live in rural areas of the Sambirano. Such children experience problems characteristic of migrants in general, yet they are more vulnerable because they are children.

Outbreaks of njarinintsy possession have accompanied this recent trend. Within the last two decades outbreaks of mass possession have occurred in local schools, and the most common victims of these reckless and dangerous spirits are adolescent girls. Throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s, as many as thirty students became possessed at one time. In several instances, school officials closed down the schools until the spirits could be appeased. Although the frequency of njarinintsy possession in Ambanja has decreased in recent years, several cases are reported annually in at least one of the three local junior and senior high schools. Unlike tromba possession, which is established and ordered, njarinintsy possession is erratic and disordered, and its victims exhibit behavior that expresses the chaos inherent to their daily lives.

Reports of similar outbreaks of group or mass possession appear elsewhere in the anthropological literature and, typically, these occur within such institutional settings as schools (Harris 1957) and, more recently, factories (Grossman 1979; Ong 1987, 1988). An assumption underlying these studies is that issues of power and powerlessness are central to mass possession movements. As with earlier discussions of tromba in this study, the significance of power for njarinintsy possession must be investigated in reference to two axes, one defined by a historical development from past to present and the other including different levels of social experience: the community, the family and the schoolyard, and the individual. Elsewhere I have argued that conflicting moral orders in this community give rise to an anomic state (Durkheim 1968) in these children, which may have severe psychological consequences (Sharp 1990).[1] This chapter will illustrate, first, that children and adults have very different possession experiences, and thus njarinintsy provides additional information on the structural significance of tromba in this community. Second, the dangers associated with njarinintsy possession uncover other dimensions of disorder in this community which, in turn, have implications for the future. These children’s experiences reveal the hidden underbelly of town life, deepening the understanding of problems associated with gender, polyculturalism, and colonialism which have thus far been explored only through adults’ eyes. In order to resolve these children’s problems, adults of diverse origins and backgrounds pulled together, drawing upon Sakalava authority to surmount chaos and reestablish social order.

| • | • | • |

The Possessed Youth of Ambanja

Although tromba possession was the main focus of this research, my attention was often drawn to the njarinintsy, volatile and unpredictable spirits whose most frequent victims are adolescent girls. No mass outbreaks occurred during 1987; thus, this discussion of njarinintsy possession in the schools is based on interviews with more than one hundred informants, including spirit mediums, schoolchildren, their parents, other family members, teachers, and other school officials. The data collected focused on three areas: informants’ accounts of mass possession occurring one to six times a year between 1975 and 1980, involving anywhere from three to thirty students; interviews with five established mediums who, in the past, had experienced possession sickness and four women who had recently been struck by possession sickness (see Appendix A); and my personal observation of five cases of njarinintsy in 1987.[2] Although tromba possession is an experience shared by many adult women, the following generalizations can be made about njarinintsy: the majority of its victims are between thirteen and seventeen years of age; they are school migrants who have come from Ambanja from neighboring rural villages; and they are female and, usually, pregnant and unmarried at the time of possession. The stories of Angeline (chapter 5) and Monique (chapter 7) are typical of njarinintsy victims. Sosotra’s story, which follows, provides yet another portrait.

Sosotra and the Njarinintsy

One afternoon, while my assistant and I were interviewing a medium in her home, we suddenly heard the sound of wailing coming from a small house made of palm fiber which was located directly across the yard. Two women who were sitting with us exclaimed simultaneously that there was a njarinintsy (“misy njarinintsy é!”) and so we all quickly stood up and went outside to see what was happening. It was Sosotra, a young Sakalava woman of nineteen who lived next door. She had joined us on previous occasions while we discussed tromba and other forms of possession. At these times she was generally quiet and sullen and often complained of nightmares(nofy raty), headaches, and dizziness. Although my informant had counseled her to consult either a moasy or a tromba medium for these problems, Sosotra did not pay much attention, often rising abruptly (and rudely) in the middle of conversation and walking home without saying goodbye. Neighbors often commented that she was odd (adaladala), but they pitied her because she was clearly troubled by possession sickness. During the last month or so it had also become clear to all of us that she was pregnant. No one had any idea who the father was.

On this afternoon Sosotra behaved in a manner that was very different from what I had witnessed previously. She suddenly burst from her house and fell on the ground, thrashing about, wailing and then shouting fragmented words that were impossible for any of us to understand. When we tried to get near her to calm her down she only became more violent. Finally, a friend of hers, along with two older women in their fifties, lept upon her and held her down until she became quiet. Eventually her aunt (MoSi), with whom she lived, came home, and she immediately arranged to take Sosotra in a taxi to a nearby village in order to consult with a tromba medium who specialized in possession sickness. She also sent for Sosotra’s mother, who arrived the next day, accompanied by two young children. Two days later I saw Sosotra and she appeared quiet, but still sullen, unwilling to talk to me or my friend, who was her neighbor, about what had happened.

Sosotra’s aunt then gave the following account, while Sosotra’s mother was at the market buying food for the evening meal: “These last few months have been very difficult, very hard [sarotra be,mafy be]. Sosotra lived here in town by herself for two years, sharing a room with two schoolmates. She started to get in trouble, staying out all night and skipping classes. When I moved here last year she came to live with me.…Her parents had hoped that she could finish her schooling this year but she soon became very agitated and unhappy in school. Her teachers and neighbors said sometimes she would refuse to go to classes at all; on other days she would come home by late morning.…She wouldn’t eat all day and then she’d go to the disco with her friends and stay all night. Three months ago the njarinintsy started, and she had to drop out of school a month before the term ended. I haven’t known what to do.…Njarinintsy is very difficult and it is dangerous.…We took her to a tromba [medium] and the njarinintsy came out [miboaka] and spoke to [the tromba spirit]. The tromba said, ‘My grandchild [zafiko], why are you bothering this girl? Leave her alone, leave her in peace! What do you want from her?’ I was frightened [mavozobe] for her, but now it all seems pretty funny…the njarinintsy said he wanted Sosotra for his girlfriend [sipa]! but when he saw how unhappy we were, he promised to leave if we gave him some presents. We promised to leave some honey and soda pop near a sacred madiro tree for him, and then he departed. Then Sosotra fell on the ground, delirious but calm, and in the past few days she has slept soundly, without any signs of possession.”

Sosotra’s story parallels that of many other njarinintsy victims: she is under twenty, a school migrant from a village, and pregnant. Her story also parallels those of other girls who were involved in outbreaks of mass possession.

Schoolyard Posssession

Today njarinintsy possession is most common at home; it assumes its most dramatic form in the schoolyard, however, where it also has widespread impact on the community. This is a relatively new phenomenon in Ambanja. The earliest report that I have recorded from northern Madagascar occurred in 1962 in a school in Diégo. Most informants say that they first heard of njarinintsy in the 1970s and that it was brought by Tsimihety migrants. Of the seventeen teachers and school officials interviewed who had either grown up in the area or who had come to Ambanja within the last ten years, all but two reported that they had never heard of this type of possession elsewhere. Of the two who had, they both said that njarinintsy behavior has changed considerably: fifteen to twenty years ago njarinintsy were, for the most part, clowning spirits. As one teacher, who grew up in the north, said, “When I was much younger I would occasionally see [students possessed by] njarinintsy sitting outside a school and playing guitars, calling to passersby to come and sing and dance with them.”[3] In more recent years, however, they have become increasingly violent. Within the last decade, possession in Ambanja’s junior and senior high schools has become so commonplace that two of the three school principals have formulated policies for handling it.[4]

A typical scenario[5] reads as follows: a teacher asks a student to perform a task, perhaps an assignment at the board. The student, instead of responding, will suddenly start to wail. Eventually the sound will grow louder, and she will sob, scream, or yell obscenities. She also might stand up or run about the room. As one teacher who witnessed a case in class explained: “I had asked this girl to read a passage from a French book. Instead she started to cry and then scream! I didn’t understand what was going on—I come from Antananarivo and I had never seen such a thing. When she stood up I became scared.…Two students ran out of the room and a third told me to come, too, so I left and went to look for help.” Often four or five boys will struggle with the njarinintsy victim in an attempt to hold her down. Word travels fast when such an outbreak occurs, so that usually a school official will arrive to help. A school principal explained: “If the girl fails to answer any questions and it is clear that she is possessed, sometimes the only thing to do is to slap her across the face.…I remember I had to hit one student three times! Then she was suddenly quiet and confused, calmly asking me where she was and why she had just been struck.”[6] After the incident is over, or at least once the girl is under control, a group of friends will escort her to the home of her parents or other close kin (who most often live in the neighboring countryside), so that these family members may take over. Even though the girl may appear calm, the spirit will stay with her, shifting from dormant to active states until a healer coaxes it to leave.

Njarinintsy is thought to be very contagious, and from 1975 to 1980, mass outbreaks of njarinintsy possession were common. When a njarinintsy victim starts to wail, other students will run from the classroom or be ordered to do so by a well-informed teacher or school official. On several occasions fifteen to twenty students became possessed at one time. Sometimes up to four boys were affected, but in all cases the outbreak was initiated by a girl, and girls always formed the majority. Angeline (see chapter 5), for example, became possessed four times in one month, and during two of these episodes as many as ten other students also became possessed, including one boy. At the height of these outbreaks in Ambanja, njarinintsy spread from the junior high school and moved across the street to the primary school.

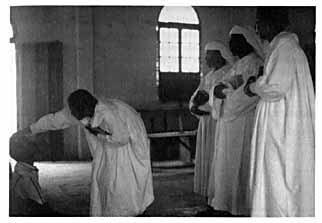

After attempts to treat njarinintsy possession on an individual basis failed to eliminate this problem in the schools, a group of concerned parents responded by requesting that school officials also become involved. This group of adults decided to call in a powerful moasy to visit the school and determine the causes of mass possession. He said that local ancestors (tromba, razan̂a, and other spirits) were angry, for when the school was built by the French no regard was paid to the sacredness of ancestral ground. During construction several tombs had been moved, and a few were destroyed. This specialist insisted on the necessity of performing a joro ceremony to honor these ancestors. This decision was an unusual one, for school grounds were hardly considered an appropriate setting for this ceremony. Nevertheless, school officials consented. An ox was sacrificed and members of the community gathered to sing to and praise the ancestral spirits, asking forgiveness and permission to continue to work at the school. A photographer was also hired to take a series of pictures to commemorate the event. Following these actions, the frequency of njarinintsy possession dropped considerably that year, with only a few students still experiencing possession fits. Eventually school officials, the possessed students, and their parents met once more with a kalanoro medium, this time in secrecy at night in one of the classrooms, to appease the njarinintsy one last time.[7] This collective response came from adults of diverse origins, including Sakalava and vahiny parents and schoolteachers and officials, several of whom were from the high plateaux. Their chosen course of action reinstated social order and cohesiveness in the schools. It also led to the reassertion of local Sakalava ritual authority over domains previously usurped by a foreign colonial power.

Njarinintsy Possession and Social Status

As discussed earlier in chapter 5, the causes for, behavior of, and responses to tromba and njarinintsy spirits are quite distinct. Njarinintsy is a form of possession sickness that requires immediate action. Kin must step in to care for the victim before serious harm befalls her. They may need to take her to a series of healers in order to have the spirit (or spirits, since njarinintsy may occur in groups of seven) driven from her. She must be watched closely, and great care must be exercised to ensure that the spirit has departed permanently. If not, she may go mad or die. Most often njarinintsy posssession is caused by fanafody raty or bad medicine. As a result, it is necessary to determine whether possession was brought on by an adversary or if the victim accidentally came into contact with fanafody that was intended for someone else. Another cause may be that the njarinintsy has been sent by a tromba spirit because the victim has been resisting possession (as was true of Angeline). If this is the case, additional steps must be taken to instate her as a tromba medium.

A comparison of the qualities of tromba mediums and njarinintsy victims reveals that gender, age, and other aspects of social status vary for these two forms of possession. Adult female status in Ambanja is defined by crossing thresholds marked by marriage (common law or otherwise) and childbirth. Women who have attained this status form the majority of female tromba mediums. Marriage also provides the idiom for describing tromba possession, since a spirit is said to be the medium’s spouse. Furthermore, through tromba possession a woman’s social ties are enhanced, so that she joins a wide network of other mediums of diverse ages and backgrounds. Also, if she chooses to become a healer, her status in the community is elevated.

The majority of njarinintsy victims, however, have never been married and have had no previous possession experience. Instead, many of these girls are single and pregnant at the time of possession (as was true with Angeline, Monique, and Sosotra). In addition, unlike tromba, njarinintsy possession is a temporary, incomplete form of possession. It is a type of possession sickness in which the possessed is a victim who requires assistance from others at a time of personal crisis. Njarinintsy spirits are not accepted companions of their victims, nor do they assist them in times of need, as do tromba spirits. They are malicious and destructive.

The data recorded in figure 7.1 (chapter 7) and Appendix A reveal several trends regarding njarinintsy. Common themes emerge in the histories of women who have experienced both possession sickness and tromba mediumship and those who have experienced only the former. These two groups can be compared in terms of age of onset of possession, schooling, tera-tany or vahiny status, and history of fertility-related traumas.

First, five of the eighteen female tromba mediums (Angeline, Leah, Marie, Beatrice, and Mariamo) have been afflicted with possession sickness (two of them have experienced it twice). In the case of all five women, possession sickness precipitated mediumship status, which followed shortly afterward: all five have Grandchildren spirits, and the fifth and oldest (Mariamo) has a more prestigious Child spirit. Leah and Marie have each been struck a second time since instating tromba spirits. Year of birth is another determinant for this group: possession sickness has not been experienced by mediums who were over the age of thirty-four in 1987, reflecting that this is a relatively recent phenomenon in Ambanja, that it affects younger women, and that recently it has begun to precede tromba possession.

Age, school experiences, and problems involving romance and fertility also affect the timing of episodes of possession sickness among these (now) established mediums. Angeline, Leah, and Marie were first struck with possession sickness between the ages of seventeen and twenty; Beatrice and Mariamo at thirteen and twenty-six (or thereabouts), respectively. Marie experienced possession sickness three months after the difficult birth of her first child. Angeline was struck after falling in love with her teacher, who left to continue his studies elsewhere while she was expected to stay behind and finish school. Finally, social status is a factor. The women in this first group are either tera-tany or the children of settlers: Angeline, Leah, and Beatrice are Sakalava from a village near Ambanja, Ambanja, and Nosy Be, respectively. Marie is the child of Tsimihety settlers, whereas Mariamo was born of a Comorean father and Sakalava mother in Ambilobe. Four of these five women have completed at least some level of junior high school and the fifth completed primary school.

The second group (Vivienne, Sylvie, Victoria, and Sosotra), composed of women who have been struck by possession sickness only, are predominantly Sakalava: Sylvie was born in Ambanja and Victoria and Sosotra are from nearby villages. Vivienne is the child of a Sakalava mother and Tsimihety father and originally came from Ambanja.[8] The ages at which njarinintsy episodes occurred for this second group of four women range from fourteen to early thirties; two out of four (Vivienne and Sosotra) were in junior high school. In reference to fertility, Sylvia was struck by njarinintsy one week after a miscarriage, Victoria following an abortion, and Sosostra following her first pregnancy by a secret lover when she was still single.

Several themes emerge if these two categories of women are compared. First, three out of five mediums (Angeline, Leah, Marie) were first struck by possession sickness while they were adolescents enrolled in junior high school. Among those affected to date only by possession sickness, two out of four (Vivienne and Sosotra) were also in junior high school. For all five women questions surrounding female adult status or fertility were important issues at the time. If the specific school experiences are compared between these two groups, three of the five students were what I refer to here as “child” or “school migrants”: Angeline, Vivienne, and Sosotra each came on their own from villages to continue their education in Ambanja. As will become clear below, the relationships between school migration, adult status and fertility, and possession sickness are part of a larger picture framed by historically based national and community forces. Likewise, the responses to these possession episodes are linked to the internal logic of local culture, in which Sakalava customs provided an appropriate response to problems that arise from powerlessness.

| • | • | • |

The Disorder of a Fragmented World

The members of this community, be they tera-tany or vahiny, young or old, must struggle at some level to cope with forces that challenge notions of cultural and, ultimately, personal identity. The combined forces of colonialism, polyculturalism, and subsequent métisization have led both to the erosion of Sakalava cultural values and to a blurring of ethnic boundaries. Newly arrived migrants must become enmeshed inlocal networks, seeking out friends and relatives who come from the same region of the country. Others attempt to become Sakalava through changes in behavior, dress, and dialect and by participating in such Sakalava institutions as tromba ceremonies. The dilemmas associated with economic survival and social integration frustrate many vahiny. As earlier descriptions of settlers’ stories show, even those who feel content (tamana) in Ambanja continue to be regarded as outsiders by local tera-tany. The most vulnerable group in this context consists of children living alone, since they have neither adult guidance nor the skills to solve the problems associated with town life. The young girls who become possessed by njarinintsy are the most visible victims of this process because they suffer the consequences of unexpected (and unwanted) pregnancies.[9] They are faced with a complicated and tangled set of desires and expectations; in their possessed states they mirror the problems inherent to schooling on the coast.

Colonial Policies and National Trends: Educational Dilemmas

Problems associated with education characterize the lives of children. In Ambanja, they run beyond those associated merely with high performance in school. In recent times, severe constraints levied by political and economic forces have imposed new frustrations on students. These problems are rooted in changes that occurred during the colonial period. A comparison between today’s schoolchildren and those of past generations illustrates this.

Under the French, schools were built to serve Malagasy students. Primary (FR: primaire) education was mandatory, and the first school for Malagasy in Ambanja was built in 1908, only a few years after the town was founded. An extensive network of primary schools was established throughout the island, with schools located even in the smallest villages. A few students were able to continue on to junior high (collège), high school (lycée), and, ultimately, to professional schools. These children joined a privileged group of students who were groomed to form a future elite class of civil servants. In the Sambirano, special preference was shown for the children of local royalty and others whose parents already worked for the colonial administration (see Crowder 1964, and Gifford and Weiskel 1974, for discussions of French colonial education policies elsewhere in Africa; see also Fallers 1965, especially chaps. 5 and 7ff).

Junior high and high schools were few in number and were generally located in urban centers so as to serve the region. As Malagasy children moved beyond primary school they left home to live in the provincial or national capitals. They were housed in dormitories, where they were placed under the strict supervision of members of a French ruling class. The school was regarded as the primary arena for the application of colonial assimilation policies, whereby French values were promoted and local culture was undermined (cf. Crowder 1964). The education of girls, for example, was comparable to that of French finishing schools, for they were taught homemaking skills and became well versed in the manners that were thought to be essential for women living in a cosmopolitan French society. As Alima, a member of the Bemazava royal lineage explained: