Tomás Imaz and the Vision Trips

Tomás Imaz Lete, a thin bald man in his early fifties, first came to the public eye when he was arrested and fined for making a scene with Marcelina Eraso on the train. By then, October 1932, he had been a leader in the vision community for at least seven months. The believers nicknamed him "Tximue" because of a certain chimpanzee-like quality to his face and ears; they heard rumors that he was connected to high church officials. Imaz was a real-estate broker based in San Sebastián. While he was not a publicist, he was very much an organizer, and he was one of the few believers to follow his convictions to their logical consequence. If indeed the world as everyone knew it was going to come to an end, and soon, with a great chastisement and a great miracle, there was no point in

Tomás Imaz, on left, with José Garmendia in vision at

Ezkioga, winter 1931–1932. Photo by José Martinez

selling real estate. So he liquidated his assets and slowly spent his funds on the seers and the believers.

Starting in June 1932 Imaz rented buses and invited seers on pilgrimages. He took several trips to Zaragoza to speak to Hermana Naya, venerate the Rafols crucifixes, and pray for Spain to the Virgen del Pilar. The French author G. L. Boué met the seers, including José Garmendia and Benita Aguirre, on their return from a trip on 25 June 1932 in which Benita had visions of the Virgin and Gemma Galgani. José Garmendia's declarations on these expeditions would have confirmed Burguera's worst fears about uncontrolled seers and uncensored messages:

BLOOD OF THE DEVIL

Declaration and vision on this day taking place on the fifth pilgrimage organized by D. Tomás Imaz with seers of Ezquioga to the Santo Cristo Desamparado of the Venerable Madre Rafols in Zaragoza.

Zaragoza, 22 September 1932

On the way, after passing Tudela in the bus, the Most Holy Virgin made me aware that although she had forbidden the devil from bothering us pilgrims on this trip, he had come close to the bus, and Saint Michael had wounded the brazen devil with his sword on the right side of the neck, and from that wound fell two great drops of blood that stained the outside of the windshield of the bus; and when the infernal dragon returned

again later, Saint Michael hit him again, and blood spattered the hood of the bus. All these bloodstains remained very visible for two days, as all the pilgrims present have been able to confirm.

The seer José Garmendia Tomás Imaz; Jesús Imaz, priest; Rosario Gurruchaga; María Luisa; José Antonio Múgica; Juana Múgica; Martí Berrondo; José Azaldegui; Marcelina Eraso; Vicente Gurruchaga; Francisco Otaño, priest .[68]

Boué, 60, 78-79; Ducrot, VU, 23 August 1933; B 561, 711; Benita to García Cascón, 28 June 1932, in SC D 113-114. Garmendia vision in SC D 52-53 and ARB 216.

Here we have another rare glimpse of a clandestine group. Besides Garmendia there are at least five second-rank seers, the two (unrelated) Gurruchagas, María Luisa of Zaldibia, and Marcelina Eraso, Juana Múgica was a believer from Zaldibia, and José Antonio Múgica was the baker from San Sebastián detained two weeks later with Tomás Imaz and Marcelina on the train. The baker and his brother frequently accompanied Garmendia, and Marcelina stayed at their house in San Sebastián. Jesús Imaz Ayerbe had been a missionary overseas; he had moved to San Sebastián in 1928, where he was the chaplain to a community of nuns. On 18 July 1931 he had been cured of a chronic stomach ailment at Ezkioga. Otaño we know as Ramona Olazábal's spiritual director. Martín Berrondo and José Azaldegui were believers. So we have a gathering of seers and believers, priests and laypersons, urbanites and rural folk, men and women. There was a mix of class as well. The real-estate man and the retired missionary were listening intently to farm girls and barely literate factory workers. As for the blood of the devil, it is no coincidence that it was seen on a trip to see the crucifix of Madre Rafols; that crucifix was supposed to have been found with blood on it. Believers proudly showed the stains on the bus to townspeople in Ordizia.[69]

For J. Imaz, BOOV, Guía Diocesana, 1931, p. 116, and B 301. For garage, Ducrot, VU, 23 August 1933, p. 1331. The devil appeared by the bus just beyond Tudela in the Ribera, the domain of the left.

Since Tomás Imaz spoke Basque, he could connect better with the rural seers than Burguera or the Catalans could. At the vision sessions he frequently led the rosary. His special protégées in 1932 were Esperanza Aranda and Conchita Mateos, in addition to José Garmendia. He introduced Juan Bautista Ayerbe to them and accompanied him to their séances. Tomás's belief in the apocalypse made him fearless in defying the government, the church, Burguera, and social convention. Burguera concluded that Imaz was doing the work of the devil. José Garmendia eventually had a revelation that "the seers who go with I[maz] are betraying her and us."[70]

For Imaz fearlessness, Ayerbe to Cardús, 5 May 1934; Garmendia's vision against Imaz, 24 June 1933, B 639; also one of Esperanza Aranda, 20 April 1933, to halt trips to Zaragoza and Aralar, B 711, B 282 n. 1.

Imaz's trips were a way to avoid parish, diocesan, or governmental control. He took seers to places like a sympathetic convent in Alava where, with discretion, they could have visions in peace. Later he was reduced to leading pilgrimages on foot to Aralar or Urkiola. And when his last money was gone and the world had not yet come to an end, he lived on the charity of the believers.[71]

Seers also went to Limpias and Lourdes, possibly with Imaz.

The shrine of San Miguel de Aralar is near the peak of Mount Aralar between the Barranca and Gipuzkoa. For the seers and followers this isolated site was always a safe haven, and with or without Imaz they made numerous trips there, even when it was snowbound. At that time San Miguel de Aralar was the great shrine of Basque Navarra. In an annual ritual of great emotional impact its thaumaturgic image of Saint Michael was carried from town to town in the province; this veneration stitched together the fabric of Navarrese identity. In each town the image would be met with a procession and would be carried to the parish church and to the houses of invalids. In Iraneta devotion to Saint Michael was "terrible ," according to the town secretary, Pedro Balda, who described annual fiestas during which the town council went to the shrine on foot. As a youth, Balda himself carried the image down from the shrine and from Iraneta to Irurtzun. In Betelu too there was "a blind faith in the Saint Michael of the Basques." On the Gipuzkoan side of Aralar there was also devotion, if not so thoroughly programmed. The parish church of Ezkioga, dedicated to Saint Michael, has a sixteenth-century plateresque reredos with reliefs of the apparition of Saint Michael at Monte Gargano. In Ataun people made promises to the saint and used ribbon measurements from Aralar for healing. In Oñati a youth dressed as Saint Michael, complete with sword, walked in the Corpus Christi procession, as did boys in Good Friday processions in Andoain and in Azkoitia.[72]

Pedro Balda, Alkotz, 7 June 1984, p. 7; Lidia Salomé, Betelu, 7 June 1984, pp. 2-3; Barandiarán, AEF, 1924, pp. 165, 168; and Etxeberria, AEF, 1924, p. 71.

People thought of Saint Michael as a precursor of the end of time, a warrior captain against the enemies of the church. At Ezkioga the photographer Joaquín Sicart distributed a picture of the saint with these words: "This image, approved by His Holiness Pius IX in 1877, represents the Archangel Saint Michael, sent by the holy spirit to remove the obstacles to the reign of the Sacred Heart."

Saint Michael's shrine at Aralar was a symbol for all Catholics of the region. When he was bishop of Pamplona Mateo Múgica wrote a stirring pastoral letter in praise of the saint. It opened with Apocalypse 12, verses 7 and 8: "And there was a great battle in the sky: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon, and the great dragon was slain, that ancient serpent, who is called the devil." In the letter the bishop discussed the cult of angels and the apparitions of Saint Michael in Italy, in Normandy, and in Navarra. (In the year 707 the saint was said to have appeared to a noble warrior living on Mount Aralar as a hermit in penance for having slain his wife.) Bishop Múgica's predecessor had revived the shrine's brotherhood and Múgica himself had built a road, brought electricity, and planned an illuminated cross for the remote site. He had seen the thousands of Navarrese and Gipuzkoans who gathered at the shrine on May 8, September 29, the last Sunday in August, and the first Sunday in September. He concluded the pastoral letter with an intemperate attack on blasphemers, adulterers, those who work on Sundays, young libertines who attend theaters, movie houses, and dance halls, overtolerant parents, indecently dressed girls (those with bare arms and short skirts), makers of short skirts, drunkards, skinflints, thieves, exploiters

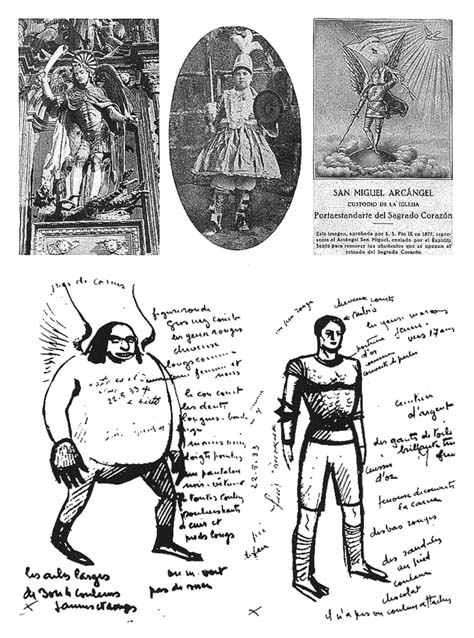

Saint Michael: top left, patron saint of Ezkioga parish church (photo

by Joaquín Sicart); top center, boy saint Michael from Good Friday

procession, Andoain, 1915 (from Anuario de Eusko-Folklore, 1924,

courtesy Fundación Barandiarán); top right, holy card sold at Ezkioga,

ca. 1932 (printed by Daniel Torrent, Barcelona); bottom, the devil and

Saint Michael as seen by Luis Irurzun and drawn by J. A. Ducrot (from VU,

30 August 1933, all rights reserved)

of workers and the poor, gossips, proud and worldly people, spiritists who worship the devil, as well as apostates, heretics, schismatics, and sectarians. On all of these he called down Saint Michael's sword.

Writing in El Pensamiento Navarro on 17 July 1931 a cathedral canon equated Michael of Aralar's struggle with the dragon and that of Catholics with the Second Republic. In doing so he anticipated by one week the visions of Patxi and others. For the canon Saint Michael of Aralar was

the shrine of our beliefs and the bastion of our traditions, whence resounds the old triumphant cry, "There is no one like God!" whose echo, rolling from peak to peak and spreading from valley to valley, has gotten the sacred militia of your brave men on their feet, ready to struggle fearlessly with the dragon until they slay it or cast it, defeated, in its cave.[73]

Múgica, "San Miguel"; Mugueta, PN, 17 July 1931.

For conservative Basque Nationalists too Aralar was a rallying point. Luis Arana Goiri, the brother of the founder of the Nationalist party, had Saint Michael named the patron saint of the party. In August 1931 party ideologue Engracio de Aranzadi wrote that the shrine was "the point of vital union of all Basques" and he warned people not to abandon "their invincible Chieftain, the Angel of Aralar, at a time when the race needs the help of all its members in order not to succumb before the number, power, and hatred of its eternal enemies." The great advantage of Michael of Aralar as party patron saint was his attraction for the Navarrese, doubtful members of a greater Euskadi.[74]

Aranzadi, EZ, 20 August 1931. At the Nationalist fiesta at Aralar on 20 August 1933 about a third of the eighteen thousand persons were from Navarra; PV, 25 August, p. 8.

The visions of Saint Michael battling dragons and devils in the sky at Ezkioga pointed to Aralar as a place of contact between the celestial and regional landscapes. Michael figured prominently in the visions of the seers from both slopes of Aralar, those from Ataun and those from the Barranca. In the visions Michael was the Virgin's great auxiliary, and when the great miracle was to occur, it was he who would explain it and later carry out the chastisement. So when vision meetings were forbidden at Ezkioga, Aralar became a logical alternative for Tomás Imaz and the seers.

There were other private vision places. In February 1933 police arrested the inhabitants of a flat in Bilbao because people were going there to see a miraculous Christ. By 1934 there were also regular meetings of believers in San Sebastián. And two male seers held sessions in the house of José María López de Lerena in Portugalete the first Fridays of every month. In Oñati women from town and farms said the rosary in a chapel of the parish church of San Miguel and embroidered a banner with the Virgin of Aranzazu and Saint Michael. Thus they prepared for the day of the great miracle, when they would come into the open and show their colors.[75]

Bilbao: "La Policía descubre un Ezquioga establecido en un quinto piso," VG, 12 February 1933, p. 5; San Sebastián: Sarasqueta, VG, 10 April 1934, refers to "a certain San Sebastián gathering-place for the pious"; Portugalete: lifetime servant of the López de Lerenas, interviewed by telephone, 7 May 1984; Juana Urcelay, Pamplona, 18 June 1984, p. 4.

In Ormaiztegi a wealthy lady held prayer sessions almost continually in her large house; she had a chapel-like prayer room with an altar and stations of the cross. Seers, two of them young women servants, would go into trance. On special holy days the dozen or so believers might hold a procession in the walled garden and sing hymns. Those attending included shopkeepers from Urretxu and Zumarraga. Persons involved in this circle describe a closed, intense world where every illness was treated with holy water from Ezkioga and every death lit by candles that had previously been lighted and blessed during visions. Some families were divided, and believers had to pray extra hard and have extra masses said so nonbelieving relatives would not go to hell. The sick offered their illness to God as sacrifices, and some who died were considered saints and intercessors in heaven. The believers contributed money and jewels for liturgical ornaments and a chalice for the shrine planned for Ezkioga. The host died in 1966.

Zegama was another center of support for the Ezkioga visions. This large township had a big new Carlist community center, complete with movie theater and bar. Relics and a statue of the Carlist general Zumalcarregui were in the parish church, where the boys in catechism class could put on the general's beret and the best one got to touch the relics. The religious activity of children was highly organized, both informally in fiestas and by the church in sodalities.[76]

The poet José Azurmendi, San Sebastián, 4 February 1986; Gorrochategui, AEF, 1922; and Gorrochategui and Aracama, AEF, 1924, pp. 108-109.

In 1924 a priest reported that only ten persons did not go to church at all, but he was alert to the railroad, the paper mill, and the alcohol factory as threats to community morality. The women were devout, but most men were indifferent. The clergy worked hard to counter the inroads of modernity: from 1918 to 1924 almost every house enthroned the Sacred Heart of Jesus. In this effort the clergy could bank on Zegama's strong Marian traditions, which included an overnight pilgrimage on Pentecost Sunday over the mountains to Our Lady of Aranzazu.[77]

Gorrochategui and Aracama, AEF, 1924, p. 103. For Aranzazu see Guridi, AEF, 1924, pp. 99-100; and Gorrochategui, AEF, 1922, p. 51.

In 1931 several of the many diocesan priests born in Zegama supported the visions. One of them, the parish priest, took down the messages of Zegama seers Marcelina Mendívil and the eight-year-old boy Martín Ayerbe. Burguera was much impressed by the boy's visions of dead children: "He gives minute details about them to their families, which is why these families and others who know about the prodigies believe him."

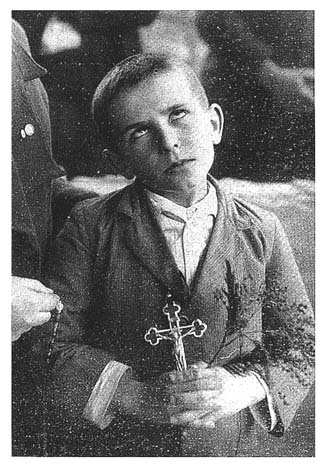

Martí Ayerbe had visions both in Zegama and at Ezkioga, where his picture was sold on postcards. Like the other seers, he saw not only the Virgin, but also Christ, Saint Michael, other angels, and Saint Paul (walking among the people with sword in hand, a crown on his head, in white clothes and white shoes). The parish priest was intrigued by Martín's visions of a book the Virgin was reading that the devil wanted to destroy; he assumed it was the one Burguera was writing. The boy's vision on 17 October 1931 shows one way the visions could spread among children. He told a farm girl, aged twelve, from

Martín Ayerbe of Zegama in vision, ca. 1932. From Nouvelle

Affaire, fig. 27. Photo by Raymond de Rigné, all rights reserved

Zumarraga that the Virgin had appeared over her head and instructed him to tell her to pray six Hail Marys on her return and to go every day to Ezkioga, where she too would see the Virgin.

In January 1933 when Martín was in vision in catechism class in a chapel, he saw a crucifix in a corner bleeding. According to Burguera, the other children and persons who came in, including two priests, saw the blood too. On Martín's advice, the parish priest notified Bishop Múgica, not yet in the diocese, instead of Echeguren, the vicar general. When the French photojournalist Ducrot went there in May 1933, other children as well were having regular visions before an altar in the chapel.[78]

For Marcelina Mendívil, Boué, 60, who cites a vision in Zegama on Easter Sunday, 1932, and R 59. Ducrot in VU, 16 August 1933, p. 1289 (photograph). For rest on Martín Ayerbe, B 624-628. Francisco Otaño, curate of Beizama, wrote Cardús from Beizama, 25 March 1933, "The priests of Cegama received orders from Vitoria prohibiting access to the place, but then a counter-order a few days later permitted access and asked that the bishop be informed of whatever occurred."

Finally there was a vision substation in the mountains of Urnieta coordinated by the town secretary, Juan Bautista Ayerbe. In 1933 and 1934 Conchita Mateos, Esperanza Aranda, the servant Asunción Balboa, and others sporadically held sessions in houses there. Gradually Ayerbe became more daring. The first news

came from the local stringer of El Pueblo Vasco on 1 December 1934, under the leader "Another Ezquioga?"

It seems that part of the stream of tourists has been diverted to this town. We are assured that several persons frequently go to a certain place between the hermitage of Azcorte and Mount Buruntza, among them several from this town, and even that some go up barefoot. The visions take place not only at this site but also in two or three houses in town.

The correspondent added details the next day, reporting that the seers were adults, that some were from San Sebastián, that people went daily from Urnieta, and that after the visions the believers gathered to talk about them at a nearby farm, where the farmer was one of the seers. Few households in Urnieta were involved actively, but the correspondent named Juan Bautista Ayerbe and "Señor Imaz" of San Sebastián. Ayerbe denied the charge, and an angry lady visited the newspaper office in San Sebastián and said in broken Spanish, "Do not mess with the apparitions. Leave us in peace. We will follow the Virgin anywhere."[79]

Kale'tar bat [a man from the street, or town center], PV, 1 and 2 December 1934.

Clearly there was more than visions at stake, for three days later an explicitly political diatribe against the correspondent appeared in La Constancia . The author, I think Ayerbe himself, admitted only that the farmer and his friends were praying the rosary and doing the stations of the cross at the chapel. With the kind of vehemence that can best be aroused in small towns, he pointed out that the Pueblo Vasco correspondent was a Basque Nationalist and attributed his derision of the devotional practices to politics. By then Basque Nationalists had become allies of the Republic, and he tried to attribute their opposition to the visions to anticlericalism.[80]J. B. Ayerbe, LC, 5 December 1934.

The correspondent replied that in Nationalist homes throughout Urnieta, rural and urban, people still prayed the rosary and that monarchists like Ayerbe did not have a corner on Catholicism. He alluded to two years of visions in Ayerbe's home and cited a brief exchange that gives a sense of how difficult it was for persons going about their daily lives to contend with others who believed that the end of time was at hand.

Not long ago an assiduous male devotee of Ezquioga went up [toward Mount Buruntza] with a lady, and when they came to a farm and saw that its inhabitants were quietly eating their afternoon meal, they snapped, "What are you doing eating? The Virgin is appearing up there."[81]

Kale'tar bat, PV, 12 December 1934.

With martial law in force, all meetings required government permission. Ayerbe recklessly continued the sessions, and civil guards surprised a group praying at the chapel of the Santa Cruz de Azkorte. Three persons were fined. When the military commandant consulted with the diocese, the archpriest of the zone asked him to ban all meetings in the chapel. At Urnieta the Republic thus

came to an understanding with the church to suppress visions, and this understanding was applied in Zaldibia.[82]

PV, 15 December 1934, p. 1 (also LC, p. 8, and ED, p. 1); PV, 16 December 1934, p. 1.

Only a week later Ayerbe reconvened his group in Tolosa, where on 23 December 1934 the poor seer Asunción Balboa talked over the crackdown with the Sorrowing Mother. The Virgin told her the Basque Nationalists were to blame and would be punished and warned that bad men would throw bombs into convents. The unusually explicit politics of this cuadrilla comes out in Balboa's conversation with Jesus, who told her that King Alfonso would soon come back to reign in Spain. She also saw Thérèse de Lisieux, Gemma Galgani, and Our Lady of Mount Carmel, who said that because of the group's prayers twenty-five souls would leave purgatory the next Saturday. There was still time for many private messages for individuals.[83]

J. B. Ayerbe, "Visión de Asunción Balboa, 23 Dicbre. 1934—En Tolosa," 2 pages, typewritten, AC 213: "No quieren que reine el Rey Alfonso pero Tú dices que ha de reinar en España ... Pero sí reinará. No tardará mucho tiempo."

Starting then in 1932 Gipuzkoa had a number of groups that maintained their own parallel Catholic rituals, firm in the knowledge that a civil war would occur and that sooner or later there would be a great chastisement. Each cuadrilla met in secret, but everyone in the zone knew that such groups existed. As far as I can tell, apart from some intransigent priests, few people felt moved to do anything about them. One exception was a potter from Zegama who stood up on the vision stage at Ezkioga and shouted, "I believe in Christ but not in this nonsense!" After all, the majority of Catholics in the Basque uplands were hopeful at first that the visions were true, and huge numbers had been devout and enthusiastic spectators. Later, instead of denouncing the seers and the believers, people either tolerated or laughed at their delusions, often with grudging admiration for their piety.[84]

For Zegama man: Francisco Ezcurdia, 10 September 1983, p. 3.

I was told stories about the believers which, true or not, demonstrate how some of their contemporaries dismissed them. Women in Zumarraga told me about a couple from Zaldibia who were convinced by visions, their own or others', to reenact the flight of Mary and Joseph to Egypt. They borrowed a child and set off walking with a donkey. When they reached Valencia and found they would have to cross an ocean, they turned back. In Legorreta, I was told, a great fear swept the town one election day when a man came down the steep mountainside above the town with a blazing pine torch, and people were convinced Saint Michael the Archangel had finally descended to separate the just from the unbelievers.[85]

For Legorreta: José María Celaya, OFM, from Legorreta, Aranzazu, 1 June 1984; his father carried the torch.

But what nonbelivers, whether indignant, mocking, or tolerant, all seemed to ignore was the zest of the believers. Paradoxically, while having visions of dire events in their closed secret cells, the believers were having a wonderful time, creating pockets of social space full of goodwill and good humor. For them their rosaries, their hymns, and their vision messages were a taste of heaven on earth. In these groups the mixing of unrelated men and women, of wealthy and poor, of merchants and farmers, of San Sebastián sophisticates and rural Basque speakers, of adults and children, led to a kind of exhilaration that comes with

the breaking of taboo and convention. Rural women were suddenly on an equal footing with educated urban men, who served as their secretaries.

These people now recall their arrests as heroic. One day in October of 1937 or 1938 Juliana Ulacia and her group were caught at Ezkioga, put in a truck, and detained in a vacant house in Zumarraga.

[Woman:] How we prayed and sang! [laughs] From morning to night!

[Brother:] From that empty house they wanted to make it to heaven! [laughs]

[Woman:] Then they brought us to testify. Even the guards had to laugh. They didn't know what to do. We did nothing but pray and sing. But they had their job to do. We spent eight days like that; then when they got tired of our praying and singing, they gave us food and said, "All right, you can go home now."[86]

Elderly Zaldibia believers, 31 March 1983, pp. 10-12.

The old-time believers, their faces alight with pleasure, remembered these groups with great fondness.