Hannah Wilke:

The Assertion of Erotic Will

Parts of this chapter were presented at the University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, March 1989.

Parts of this chapter appear in Joanna Frueh, Hannah Wilke, ed. Thomas H. Kochheiser (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1989), 51–61; in Joanna Frueh, "Aesthetic and Postmenopausal Pleasures," M/E/A/N/I/N/G 14 (November 1993); and in Joanna Frueh, "The Erotic as Social Security," Art Journal 53 (Spring 1994). Material from M/E/A/N/I/N/G is reprinted by permission of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A Journal of Contemporary Art Issues, and material from Art Journal is reprinted by permission of the College Art Association.

The divinity Venus occupied Hannah Wilke for twenty-five years. She pictured herself as a contemporary goddess of love, sex, and beauty, and she also presented herself as a worshipper. Wilke's continual remodeling of Venus from a sex object into a healer of social ills and of Wilke's cancer, from which she died on 28 January 1993 at the age of fifty-two, is an assertion of erotic will.

Wilke's Venus Envy (1980) recalls Gustave Courbet's Woman with a Parrot (1863). In both works a female nude with luxuriant tousled hair lies on the floor voluptuously displaying her beautiful body. Courbet's woman exemplifies the phenomenon in Western art of male artists creating The Beauty with whom they become identified, an individualized Venus. Other obvious examples include the women painted by Boucher, Titian, Rossetti, Renoir, and Modigliani. The Beauty has verified male "genius," and art history names men as geniuses of feminine beauty, inventors through the centuries of a variety of types who, in their own time and perhaps later, can be perceived as models of female attractiveness and desirability.

Although women such as Marie-Louise Elizabeth Vigée-Le Brun, Marie Laurencin, Romaine Brooks, Frida Kahlo, and Léonor Fini have represented female beauty, their work in this area has not often been given equal status with even second-rank depictions by men. In this light, a woman's choice to deal directly with female beauty in her art does seem inspired, both as a blunt recognition of the significance of female beauty in Western art and as an indication of willingness to risk proclaiming the pleasures of beauty for the self. That is an erotic choice. The risk entails excoriation, for society still wants a woman to perform its desires and excitements, not her own. Granted, to isolate a woman's pleasures from society's is impossible, but we must be careful not to attack a woman's declaration of self-pleasure as simply an expression of a negatively feminine narcissism. No woman is that easily categorizable.

Wilke deals with Venus as a metaphor for the beautiful woman. Titles of several of her works—Venus Envy , Venus Basin , Venus Cushion , and Venus Pareve among them—indicate concern with ideal beauty, and this involvement extends into Wilke's use of herself as the model woman. The nude works she made in her thirties exhibit Wilke's body to advantage. She is whole-limbed and white-skinned, slender and well-proportioned—her breasts are neither "too" large nor "too" small, and her hips are not "too" wide. Her abundant dark hair echoes the traditional symbolism in which lush hair signifies sexual power and dark hair indicates a femme fatale. Wilke enhances her delicately attractive facial features with makeup but never overdoes it. Unshaved armpit hair emphasizes the sexy reality of her.

Wilke's beauty provides her entry into an ideal whose oppressiveness for women threatens to make her work a continuation of the "tyranny of Venus," which Susan Brownmiller says a woman feels whenever she criticizes her appearance for not conforming to prevailing erotic standards.[1] However, Wilke as usual twists language, in this case the grammar of Venus, the perfect woman. She parses the "sentence" of the female body into a statement of pleasure as well as pain. While "modeling" her beauty in S.O.S. —Starification Object Series (1974–1975), she "scars" herself with chewing-gum sculptures, suggesting that being beautiful is not all ease, fun, or glamor. Twisting chewed gum in one gesture into a shape that reads as vulva, womb, and tiny wounds, she marks her face, back, chest, breasts, and fingernails with the gum-shapes before she assumes high-fashion poses. Her "scarification" is symboli-

cally related to African women's admired keloided designs on their bodies. The Africans endure hundreds of cuts without anesthesia, and Wilke alludes to the suffering that Western women undergo in rituals of beautification.

From Una Stannard in 1971 to Naomi Wolf in 1991, feminists have analyzed the pain women "choose" in order to meet beauty standards.[2] The beautiful woman suffers, for to be a star as a woman is to bear "starification," being observed by others as a process of criticism and misunderstanding. To be "starified" is, in some measure, to be ill-starred, and the "ornaments" decorating Wilke in S.O.S. are not only scars but also stigmata. They make the model woman into a martyr.

Western culture fearfully reveres Venus in the bodies of women, and she must be crucified. Freudian theory kills the mother, not the father, despite the privileged status of the oedipal stage; artist Carolee Schneemann says Dionysus stole ecstasy from Aphrodite; and Wilke believes that Venus envy, not penis envy, has caused misery between women and men. If Venus were a contemporary divine ideal for women, rather than a clichéd sex goddess, then women would not have to struggle to invent the meaning and practice of erotic-for-women.[3]

Erotic-for-women—for women meaning that women are producers and consumers—is erotic for oneself, autoerotic autonomy whose power is both self-pleasuring and relational. Autoeroticism is apparent in self-exhibition and in women's gaze at other women unclothed. Erotic-for-women loves the female body without discriminating against its old(er) manifestations. Self-exhibition may demonstrate the positive narcissism—self-love—that masculinist eros has all but erased, and self-exhibition is a commanding statement, "Here I am. See my body," an attitude apparent throughout Wilke's work.

The beautiful resemble other groups that are feared, envied, and hated for their marks of difference. As Wilke says, "Starification-scarification/Jew, black, Christian, Moslem. . . . Labeling people instead of listening to them. . . . Judging according to primitive prejudices. 'Marks-ism' and art. Fascistic feelings, internal wounds, made from external situations."[4]

Wilke remembers that as a girl she "was made to feel like shit for looking at myself in the mirror" and that as a young woman she felt she "was observed, objectified by beauty." Her looks made her uncomfortable, and she believes she is "the victim of my own beauty," for "beauty

does make people mistrust you." A woman is "unfeminine," wrong, when she is not beautiful, yet if she is beautiful, she is still wrong. Wilke employs the peculiar inappropriateness of beauty in order to confront its wrongness. By being "improper," publicly displaying her beauty, she has used her art "to create a body-consciousness for myself," a positive assertion of her beauty, which is erotic-for-women.

"Why not be an object?" she asks, one who is aware of her I-ness, who is an "I Object."[5] Wilke's I Object (1977–78) critiques Marcel Duchamp's Etant donnés , one of his two most mythicized works. I Object is a fake book jacket, and its subtitle is Memoirs of a Sugargiver . On the front and back Wilke lies nude, legs apart, like the naked girl lying corpselike on twigs in Etant donnés . The photographs are what Wilke calls "performalist self-portraits," with artist Richard Hamilton, taken on coastal rocks at Cadaques, Spain, Duchamp's home in Europe during his later years. Two art historians see Duchamp's girl as "locked into a world of her own, like Sleeping Beauty."[6] "I object," as a declaration, protests the girl's inertness. Wilke seems to respond to the girl's deadness when she says, "I find Etant donnés repulsive, which is perhaps its message. She has a distorted vagina. The voyeuristic vulgarity justifies impotence."[7]

Etant donnés is a voyeur's dream: viewers can see the naked body only one at a time through a peephole, they look directly at the girl's genitals, and she is eerily passive. Wilke activates her image, reproducing it upside-down on the front cover. On the back cover, the image is right side up. She suggests a turning around of meaning that is a revolt against Duchamp's misshapen, desexed woman. Wilke and Duchamp both love puns and the erotic, and "I object" as a double noun—"eye object" as well as the personal pronoun—acknowledges Wilke's participation as sex object, focus of the voyeuristic gaze, and gives her piece a more explicitly erotic significance than Etant donnés . For "I object" is a statement of presence and self-knowledge, and of pride in the delight of receiving a sexually scrutinizing and admiring look and of being able to give pleasure. The subtitle Memoirs of a Sugargiver reinforces this interpretation, for Wilke sees herself as a "sugargiver instead of a salt cellar." She offers the sweets of eroticism and beauty. ("Salt cellar" is the anagrammatic play on Marcel Duchamp's name that is the subtitle of Michel Sanouillet's and Elmer Peterson's The Essential Writings of Marcel Duchamp: Salt Seller = Marchand du Sel. )

Wilke does not sell out or submit to Duchamp's genius for cool, allusive eroticism. He says that eroticism in his art has been "always disguised, more or less." Not so with Wilke, and, ironically, Duchamp's understanding of the purpose of eroticism in art better describes Wilke's work than it does his. He says that eroticism is "really a way to bring out in the daylight things that are constantly hidden. . . . To be able to reveal them, and to place them at everyone's disposal—I think this is important because it's the basis of everything, and no one talks about it."[8]

The I Object is the object of her own gaze; she knows the body through eyeing as well as aying it, assenting to its beauty. The I Object is her own voyeur and seer, who comes to realize that to seduce is to lead astray, to lure herself and others away from their habitual negations of the erotic. Wilke calls the gaze "a sparkle." The gaze is sparkling eyes, the spark of desire, an "assertion of life," she says, then continues: "To be or not to be. To look or not to look."[9] Erotic looking and sparking are not only sexual desire but also love, life force and instinct, and lust for living.

Feminism has looked at female beauty, but insufficiently. Although the popular success of Naomi Wolf's The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women (1991) demonstrates the magnitude of women's preoccupation and problems with beauty, beauty as an issue has embarrassed feminists and been low on the feminist agenda. In 1983, almost twenty years after the beginning of the second wave and ten years after Wilke created S.O.S. , scholars Robin Lakoff and Raquel Scherr admitted that they had talked about beauty "often enough. . . ,but informally and personally. We hadn't thought of beauty as a problem or a Problem—not a feminist issue, not at all something you brought up as a serious thought in public." Why? Because Lakoff and Scherr and their serious, feminist, intellectual friends had told themselves that thinking about beauty was vain, self-indulgent and self-absorbed. Lakoff and Scherr discovered, however, that beauty might be "the last great taboo, the anguish that separates women from themselves, men, and each other."[10] Susan Brownmiller earlier came to a similar conclusion in Femininity , naming "the struggle to approach the feminine ideal" as "the chief competitive arena . . . in which the American woman is wholeheartedly encouraged to contend."[11] Historian Lois Banner offers a different perspective on the situation in American Beauty . "The

pursuit of beauty," she says, "has more than any other factor bound together women of different classes, regions, and ethnic groups and constituted a key element in women's separate experience of life."[12] Wilke points to this common cause in S.O.S. by presenting photos of herself in playful yet bleakly comic poses and costumes denoting social positions and modes of glamor: a maid's apron, hair curlers, cowboy hat, sunglasses, Arab headdress, Indian caste mark, and, finally, the gum sculptures that resemble African cicatrization wounds.

Because the demand for beauty divides women and yet binds them to each other, Wilke's focus on beauty is a significant public discourse that sees everyday matters as the important concerns they are. When she says that to many people "the traditionally beautiful woman is the stereotype. . . . But nobody says there is a prejudice against beautiful people," she is stating her situation, her own separateness, which is as real for the beautiful woman as for the plain woman.[13]

Wilke's seemingly privileged position has sometimes caused misunderstanding of her art. In 1976 Lucy Lippard wrote that Wilke's "confusion of her roles as beautiful woman and artist, as flirt and feminist, has resulted at times in politically ambiguous manifestations that have exposed her to criticism on a personal as well as on an artistic level."[14] In a misogynist society the beautiful woman enjoys a kind of admiration and respect not given to many women, and such good fortune turns other women against the beautiful woman, snares them in "Venus envy," a phrase first used by Wilke in a 1980 series of Polaroid photographs.

Wilke destabilizes Venus envy, the devaluation of beauty and the erotic practiced by both women and men, by reworking myths and stereotypes about the beautiful woman. People often link beauty and femininity and regard the latter as a set of limitations. Femininity requires artifice, self-control, and perfection in bodily and gestural details, and culture constructs feminine women as needy. The beauty, then, lacks spirit and independence.

Hannah Wilke Can (1974–78) scrambles the terms of femininity. Each can, slotted to accept coins and decorated with three images of a Christlike Wilke in a loincloth, is a complex handling of the issue of neediness. The cans are for giving to a charity. They were exhibited at a 1978 performance at the Susan Caldwell Gallery in New York called Hannah Wilke Can: A Living Sculpture Needs to Make a Living . The Christ-Venus image on the can is one of twenty photographs of her 1974 performance

Hannah Wilke Super-T-Art . Venus is a Western superstar and supertart, a sugargiver par excellence . Christ is an ultimate "pinup"—pinned to a cross with nails—as is Venus, whom I referred to above as a crucifixion victim. Christ was a poor man, needy, yet a bestower of charity, caritas , Christian love. Wilke the sugargiver is also a giver of charity, even though she requests money for her Venus-Christ. With self-conscious absurdity she asks for professional support as a woman/artist. The slot/slit is a symbolic cunt, and Wilke-Venus is a sacred whore, for caritas actually means grace, specifically the grace of the

Triple Goddess, embodied in the boon-bestowing Three Graces who dispensed caritas (Latin) or charis (Greek) and were called the Charities. . . .

Romans sometimes called grace venia , the divine correlative of Venus. . . . Grace meant the same as Sanskrit karuna , dispensed by the heavenly nymphs and their earthly copies, the sacred harlots of Hindu temples. . . . Their "grace" was a combination of beauty, kindness, mother-love, tenderness, sensual delight, compassion, and care. . . .

Christians took the pagan concept of charis and struggled to divest it of sexual meanings. . . . The cognate word charisma meant Mothergiven grace.[15]

In Hannah Wilke Can the beautiful woman, the charismatic, speaks of the need for love and couples it with the self-assertions "I can support myself" and "I can support Venus, love, and beauty."

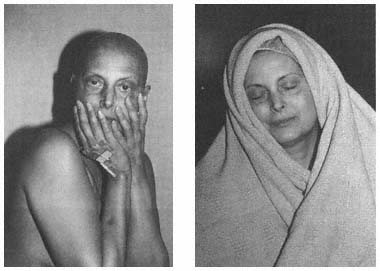

Wilke counters the "femininity" of control and perfection because she does not use beauty as a trick to cover up emotion. The beauty's face in art and the media is often bland in order to divest her of character or feeling, so that viewers can project their own desire onto the woman. Many of the So Help Me Hannah photographs (1978–81), in which Wilke, dressed only in high heels and brandishing a gun, poses in a gritty environment, show her face in strain, as a sign of alertness or fatigue, pain or expectancy. The videotape Gestures (1974) most extremely combats the stereotypical beauty's necessary inexpressiveness. Here Wilke manipulates her face with her hands, using her skin as sculptural material. She pinches, pulls, slaps, smooths, and caresses her face, shaping it into grotesque and ridiculous gestures that externalize and exorcise inner crisis.So Help Me Hannah Series: Portrait of the Artist with Her Mother Selma Butter (1978–81) is a blunt and poignant handling of women's

"perfection" and "imperfection." Wilke appears in the diptych's left segment with her breasts and chest displaying found objects that resemble "raygun" shapes she had collected as gifts for her lover, Claes Oldenburg, in the early 1970s. She scrutinizes the viewer wearing an expression that suggests that pain and sadness underlie her flawless complexion. On the right Wilke's mother has turned her face from the camera, and her body, exposed from shoulders to waist, shows not only an old woman's fragility but also the ravages of disease. Selma Butter has had a mastectomy, and the scars of her cancer surgery cover the area where her breast once was.

Wilke's "guns" and her youthfulness and beauty in the photograph allude to cover-girl shots, a phrase that reads as a pun: the beautiful, young, model woman "shot" by a camera, murdered into a still, an ideal picture of femininity, the cover girl who covers up her imperfections with emotional and actual makeup. Wilke's indication of trouble in the paradise of beauty—the guns as emotional scars of lost love—becomes real scarification in the portrait of her mother. Wilke uncovers truth—that life is also loss, that beauty changes, that age and illness must not be hidden. We see a deteriorated body that the photographer, Wilke, clearly loves, for it is very much alive with the presence of Selma Butter. Here perhaps is the necessary correlate of Wilke's erotic joy—the reality of death.

Wilke faced both of these in 1987 when she was diagnosed with cancer-lymphomas in her neck, shoulders, and abdomen—and from then till her death, in the art she made during her illness. The Intra-Venus Series (1992–93) is an astounding assertion of erotic will, which proves that erotic-for-women is courageous and radical. Intra-Venus is a rite of passage for illness and aging.

Germaine Greer says in The Change: Women, Aging and the Menopause that society provides no rite of passage for menopausal women, and she writes, too, about the pleasures of becoming a matron, which include tending to spiritual well-being and to one's garden and becoming invisible.[16] Many women say that at around fifty they did begin to feel invisible, but that, contrary to Greer's assessment, the experience is frustrating, demeaning, and shocking. (Greer advises that once a woman gets used to invisibility and understands its value, which is the pleasure of being left alone, she will be satisfied.) I read and hear about Croning rituals, in which women name and celebrate their entry into elderhood. Croning makes old(er) women visible—respected and power-

ful—to themselves, but croning is not every old(er) woman's answer to the changes that aging brings her. Croning seems like a New Age escape to some women, a romantically spiritual exercise.

Intra-Venus records Wilke's rite of passage and provides a terrifying enlightenment for the initiate-viewer. Wilke continued her autoerotic self-portrait focus in an attempt to "treat" herself with love during what she called her "beauty to beast" transformation.[17] In an erotophobic society Wilke, along with such other artists as Carolee Schneemann and Joan Semmel, originated a feminist visual erotics, and she continued into her early fifties to liberate women from the male gaze as theoretical orthodoxy and as actual hatred and misunderstanding of women's sensual and visual pleasures. These, Wilke understood, might differ from male-dominant erotic dogma if women explored and released them.

Numerous feminist writings mothered by Laura Mulvey's "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema," first published in 1975, have denied women the authenticity of their own visual and bodily experiences and have imprisoned women in the accepted reductiveness of the male gaze.[18] But the female gaze, in its genuineness and legitimacy and its relation to women's erotic pleasure, is a radical agent of change. The erotic provides the means for reinventing oneself, which Wilke does in INTRA-VENUS . She also reinvents the female nude more aggressively and poignantly than before, and her reinvention damns the patriarchal eye that fears and despises bodies of the diseased and of old(er) women.

Old(er) women suffer differently from old(er) men because female aging remains in American society what Susan Sontag called it in 1972, "a process of becoming obscene. . . . That old women are repulsive is one of the most profound esthetic and erotic feelings in our culture."[19] These "erotic feelings" are really thanatic, a kind of femicide or broadly sexual violence that, in regard to visual representation, absents old(er) women from the erotic arena and kills people's ability to imagine, let alone physically image, old(er) women with love. Although menopause is becoming a popular subject—Gail Sheehy's The Silent Passage: Menopause (1992) was a bestseller, and I've heard ads on rock radio in my gym about menopause therapy—fitness authoritarianism, cosmetic surgery, and hormone usage to "correct" dryness of skin and vagina loom as female imperatives, and menopause, which for Western women occurs at the median age of fifty, remains a powerful marker of aging.

While the onset of menstruation is an erotic passage, and American culture deems women erotically appealing for the next thirty-five to forty years of their lives, the process of menopause may initiate a woman into invisibility and extreme subhumanity. Menopause would become an erotic passage if people used their capacity to eroticize everything—and I see this as a gift, not a gratuitous banality—in order to overcome their fear of flesh that moves. To give eros is to give social security, for the erotic is necessary to psychic and spiritual survival.

Wilke provides erotic security in INTRA-VENUS by confronting and embracing flesh that has moved in an aging illness. A reclining nude in the series presents Wilke as erotic agent and object. She is a damaged Venus as in S.O.S., this time damaged by cancer and its therapies. Intravenous tubes pierce her, and bandages cover the sites, above her buttocks, of a failed bone-marrow transplant. Her stomach is loose, and she is no longer the feminine ideal. "My body has gotten old," she said a little less than a month before the bone-marrow transplant, "up to 188 pounds, prednisone-swelled, striations, dark lines, marks from bone-marrow harvesting." While an art historian could cite Renaissance martyr paintings as sources, she could also understand Wilke's vulnerable Venus, twenty years ago as well as recently, as a warrior displaying wounds and as the dark goddess, Hecate at the crossroads of life and death. Wilke has called her work "curative" and "medicinal," and she has said that "focusing on the self gives me the fighting spirit that I need" and that "my art is about loving myself."[20] The INTRA-VENUS nude shows Wilke within—intra—the veins of Venus, a lust for living in the artist's blood.

Wilke maintained that lust in a hospital, an institution that incarcerates and disciplines bodies. Informed consent is not really informed, for patients do not know or understand all the procedures they will undergo when they sign themselves into a hospital. They give their consent in a stressed if not desperate situation, which is the hope that the institution can return them to health. Hospitals turn patients into the powerless in a space and time that are not erotic, for they cut off the patient from the pleasure of relationships, intimacy, and work. Wilke eroticized her circumstances and shot INTRA-VENUS in the hospital, so she became an activist rather than a victim.[21]

In the INTRA-VENUS reclining nude Wilke resuscitates the boneless look developed by Giorgione and Titian, so she makes herself, as usual,

into a classical nude. But she is not female body as erotic trophy. This is because she—characteristically—proves that the body's boundaries are liminal and insecure—in INTRA-VENUS, through vivid and explicit pathos—and because, more than ever, she affirms, I am who I am. Bodily insecurity paradoxically becomes erotic social security, as does the ruin of the classical nude and of conventional femininity.

The erotic is not necessarily pretty. In INTRA-VENUS scars, bandages, baldness and unnaturally thin hair, and intravenous tubes signify pain. Wilke screams and stares. She crosses her arms over her stomach in self-protection, which feels sacred, a gesture of blessing, and she covers her head with a blue hospital blanket and closes her eyes in agonized and prayerful grace. As in Hannah Wilke Super-T-Art , where she poses as Mary and Christ, Wilke represents divine being in human being. Hail, Hannah, full of grace.

The erotic is beautiful rather than pretty. Femininity as a set of prettinesses, which are a set of limitations, reduces beauty to a weakness. Lakoff and Scherr say that society to some degree sees beautiful women's power as the power of the weak, because a beautiful woman's potency depends on others' perception of her appearance. She is captive to her beauty. A puritanical and simplistic feminism also sees women's beauty as a weakness. By concentrating on attacking the fashion,

cosmetics, and plastic-surgery industries as exploitative and misogynist rather than developing transformative expansions of beauty, ascetic feminism keeps beauty's reductive definition: the beautiful woman is young—at the least, youthful—thin, and managed by "beauty" products and "beauty" services. It is that definition and not beauty itself that has oppressed women. Beauty is transformable because it is erotic, and the erotic refuses to be pinned down, for it is not a specimen. In human beings the erotic can be used to radicalize the human condition and to give pleasure that enriches and enlivens the world, often in unexpected ways.

One myth about feminine beauty is that it is dangerous. A beautiful woman is stunning, striking, a knockout, and a dangerous person is powerful. That power can be radically beneficial. Throughout her career Wilke performed the indispensable power of beauty and the soundness of danger. Beauty attracts, sometimes to such a degree that the viewer feels out of control, overcome by fear or sexual desire, by wonder and sheer enjoyment, or by a magic that disturbs her peace of mind. Beauty is departure from the ordinary, provoking and luring the viewer into uncommon thoughts and feelings. Wilke seduces her audience into terror and pain, the inescapability of death, the suffering behind the mask of lovely flesh, the "exotic" grace of change. To grow old gracefully is to go into erotic decline, to be the passive beauty who is losing her looks, while to be full of grace is to be at once dangerous and comforting.

Beauty can be dangerous to the status quo, especially when women deal with it, like Wilke, in both grave and playful ways. Society does not encourage women to "play with themselves," for sexual, political, intellectual, or creative pleasure. Obeying fashion's decrees is conformist and therefore highly restricted play, but making a spectacle of oneself may well be an assertion of erotic will. For spectacles do not have to follow orthodoxies. Woman-as-spectacle fascinates and disquiets many feminists, but Georgia O'Keeffe's nun- and monk-like "habits" and Louise Nevelson's ethnic butch/femme drag were a far cry from professional sex queens' regalia whose formulaic eroticism, for some feminists, calls into question the sex icon's erotic inventiveness. Wilke's self-display, which is erotic play, has always been an affront to proper femininity, which is patriarchy's containment of female possibility. Wilke as erotic spectacle verifies female genius.