Other Congenital

Malformations of the Heart

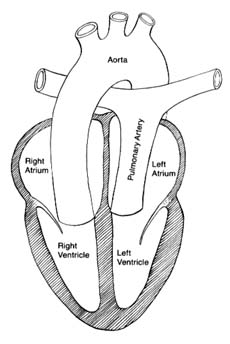

Transposition of the great arteries is a complex but common malformation. Before surgical procedures allowing partial or total correction were developed, few afflicted with this defect survived childhood. With surgical treatment patients may now reach adulthood, though their life expectancy remains greatly reduced. This malformation consists of an error in cardiac development wherein the aorta arises from the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery from the left (fig. 37). The transposition creates two separate closed circulations incapable of the exchange of gases in the blood necessary for survival: deoxygenated blood returning to the right heart through systemic veins is ejected into the aorta without being able to acquire oxygen and dispose of carbon dioxide. Blood returning fully oxygenated from the lungs enters the pulmonary artery and returns to the lungs. Obviously, this situation is incompatible with survival unless some mixing of the two bloods takes place. That need is met by persistence in the infant of the fetal communication between the two circulations, namely the foramen ovale. Occasionally ventricular septal defect is also present and assists in the mixing. Infants surviving on this oxygen-poor blood have a dark purple coloration of the skin; if a sizable proportion of the oxygenated blood is shunted into the arterial side, survival beyond infancy is possible without operation. Several methods of correcting the defect are now available, restoring normal color and permitting survival into adulthood.

Pulmonary atresia consists of total closure of the outlet for blood from the right ventricle. All the venous blood returning to the right side of the heart is shunted to the left side through atrial and sometimes ventricular septal defects. The fully mixed blood reaches the pulmonary artery and the lungs via a patent ductus arteriosus. Deep cyanosis is usually present.

Tricuspid atresia involves an absence of communication between

Figure 37. The circulation in complete transposition of the great vessels.

Communication between the two sides of the heart, necessary

for survival, is not shown in the drawing.

the right atrium and the right ventricle. Venous blood is shunted through a defect into the left atrium, and the mixed blood enters the lungs through the ductus arteriosus.

Total anomalous venous return consists of malposition of the pulmonary veins carrying oxygenated blood, which enter the right atrium instead of the left atrium, resulting in total mixing of unoxygenated and oxygenated blood. The mixture is shunted through an atrial septal defect into the left atrium and is ejected by the left ventricle in the aorta.

Ebstein's anomaly involves malposition of the tricuspid valve well inside the right ventricle, reducing its capacity. The foramen ovale often remains patent, allowing a portion of the blood from the right atrium to be shunted to the left side. The extent of cyanosis varies according to the size of the right-to-left shunt through the

foramen ovale. This lesion permits survival to adulthood and occasionally to old age.

Truncus arteriosus is a malformation of the great arteries attached to the heart. A single artery is connected with both ventricles, which communicate through a ventricular septal defect. This arterial trunk divides into a pulmonary artery and aorta. Total mixing of the blood occurs in the trunk.

Single ventricle occurs when the entire septum between the two ventricles is absent. This malformation produces complete mixing of oxygenated and unoxygenated blood.

These seven malformations have in common the mixing of oxygenated and unoxygenated blood in the systemic arteries. As a consequence, the tissues receive blood poorer in oxygen than is normal. Survivors are capable of growth, development, and some activity. Surgical treatment is now available for most of these syndromes, with variable results.

Congenital malformations without shunting of blood involve abnormalities of cardiac valves. Pulmonary stenosis has already been discussed in this chapter; left-sided cardiac valvular diseases are presented in chapter 9. Aortic stenosis is a relatively common congenital malformation, mostly as a valvular stenosis involving fusion of the three leaflets of the aortic valve. Rare variants of stenosis of the left-sided outflow segment of the ventricle include subvalvular stenosis , in which a membrane with a central opening stretches across the outflow segment underneath a normal aortic valve, and supravalvular stenosis , a narrowing of the aorta just above the aortic valve. A common anomaly of the aortic valve is the bicuspid valve (two leaflets instead of three), which has no effect on the heart and circulation but may be the site for deposition of calcium late in life and hence a cause of calcific aortic stenosis. Congenital mitral stenosis is rare as an isolated malformation, although it is seen in combination with other defects.