4—

Divine Tobacco

My fruit is better than gold, even than fine gold; and my revenue better than fine silver.

—Proverbs 8.19

Tobacco's first entry into English poetry doesn't strike the modem reader as a particularly auspicious one. In book 3 of The Faerie Queene , during a hunt, the fairy Belphoebe discovers the unconscious body of Prince Arthur's seriously wounded squire Timias:

Into the woods thenceforth in hast she went,

To seeke for hearbes, that mote him remedy

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

There, whether it divine Tobacco were,

Or Panachaea , or Polygony ,

She found, and brought it to her patient deare

Who al this while lay bleeding out his hart-bloud neare.

(3.5.32)

What could be more fleeting a reference? A plant growing in not only distant but fairy woods, and then only one of three alternatives for the herb Belphoebe actually does fetch; applied in the most unusual way, as a woundwort, not in a pipe; and Spenser's poetry never mentions the word, the novelty, again. Yet this seemingly offhand reference, and the newly introduced plant itself, had a surprising impact on later writers: no epithet for tobacco comes close to being as standard in later Elizabethan literature as Spenser's "divine,"1 a fact almost as remarkable as the meteoric rise of tobacco smoking during the same period. In 1603, the first year for which official records of tobacco importation to England survive, 16,000 pounds of tobacco passed through official channels alone.2 And a year after that, marking the new power at once of tobacco and king, James I issued his Counter-blaste to Tobacco , which denounced as England's ruination what Barnaby Rich

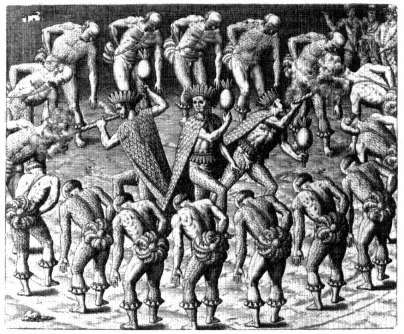

Figure 5.

An Indian rite, from Theodor de Bry's America part 3, Frankfurt, 1592. Cf.

Nashe in his Lenten Stuffe (1599): "A pipe of Tobacco to raise my spirits

and warm my brain." (By permission of the Bancroft Library, University

of California, Berkeley.)

(1617) would later call "the most vain and idle toy, that ever was brought into use and custom amongst men."3 In fact, "as the literature of the day indicates," says tobacco historian Jerome Brooks, tobacco "was nowhere more heartily taken up, after about 1590, than in England" (Tobacco 1:381). The paradoxical combination of inconsequentiality and power both in tobacco and in Spenser's reference to it seems perfectly foreshadowed by Spenser's oxymoronic-sounding epithet itself the weed is divine.4

What makes tobacco's rise to power even more impressive, and helps in part to account for James's disgust, is the fact that the sole owner of the New World from which tobacco came was the enemy, Spain. One would have expected the knowing Englishman to shy away from tobacco as a constant reminder of England's belatedness in America: not only did Spain monopolize America's treasures while England settled for a New World weed, but Spain

could further increase her fortune, and decrease England's, by selling that same weed to England. And yet tobacco in Spenser's passage represents not an exacerbation of a bad case but its cure.

A brief consideration of Spenser's allegory in the Timias and Belphoebe passage helps begin explaining how the English could accommodate tobacco's representation of their own inadequacies. For tobacco is only one of many grand trifles that figure in Spenser's passage. Neither Timias nor Belphoebe could be considered the most significant character in this or any other book of The Faerie Queene , and yet they represent what were in 1590 the two most prominent people in England: Spenser's patrons, Raleigh and the queen. And the rise to power of these figures—Raleigh the fourth son of a country gentleman; Elizabeth excommunicated, purport-edly illegitimate, and female—could seem just as miraculous as that of tobacco, almost a pledge of England's own potentiality. A celebration of his small country's enormous spiritual and imperial claims, Spenser's poem matches the paradoxicality of its subject, here in the Timias and Belphoebe passage by the lowly pastoral meant "to insinuate and glance at greater matters" (Puttenham, English Poesie , 38), and everywhere by the epic representation of "our sovereign the Queen, and her kingdom in" the nothing of "Faery land" (V 1:168). But then "divine" Spenser himself,5 the poor scholar turned laureate poet, testifies to the latent power of English trifles, producing with his contemporaries an extraordinary literature at a time when it would seem that imperial-minded Englishmen had little reason to exult.

These paradoxes are by now familiar, but what perhaps still surprises is the expectation by some Elizabethans that tobacco would not merely exemplify the divine potential of other English trifles, but actually help produce those divinities, even so far as to transform little England into a heaven on earth. Spenser's association of tobacco with Raleigh and Elizabeth suggests the real basis of England's hopes for an overseas empire, the American colony that Raleigh had already founded in Elizabeth's name—Virginia. This English foothold in the New World, its supporters claimed, would be different from Spain's American empire not only in location but in theory and practice. Thomas Cain has convincingly demonstrated that the Mammon episode in The Faerie Queene's second book represents in part Spenser's warning about New World gold

(Praise , 91-101); according to Spenser, the Spanish, in their idolatrous fashion, have blinded themselves by worshipping an earthly god.6 Cain oddly assumes, however, that Spenser is in particular warning Raleigh to "manage the gold of Guiana" temperately. The conclusion is anachronistic—Raleigh did not sail for Guiana till 1595—but, more important, misses Spenser's contrast between the gold-feverish Spanish colonies and "fruitfullest Virginia" (FQ 2.proem.2; my emphasis). The point of this chapter is to show what Spenser and his contemporaries take this contrast to mean, and why it is elaborated by talk about a smokable American "fruit." The first section of the chapter will briefly review the medical benefits tobacco was supposed to offer, and suggest why neither these supposed benefits nor tobacco's inherent pleasures can alone account for tobacco's popularity in the 1590s, precisely the period when England owned no New World empire from which to import tobacco and so was forced to buy it from the enemy who did; the second section will outline Raleigh and Elizabeth's crucial role in tobacco's popularization; and the final three sections will examine English claims about tobacco's divinity in relation to the literary tradition for tobacco inaugurated by Spenser and most fully worked out by John Beaumont's mock panegyric, The Metamorphosis of Tabacco (1602). In general, the advocates and critics of Elizabethan tobacco agree that the materially poor English are nevertheless Spain's ideological superiors, but disagree about whether tobacco will help or hurt this "fairy" superiority. The tobacco critic considers the imported weed pagan and earthly, qualities that infect England and lower its sights profoundly. A tobacco advocate like Beaumont counters that, with less persuasive claims to inherent value than gold, tobacco bespeaks the mind's power to create value, and so continually alerts the English mind (even physiologically, as I will show) to its own abilities. Later, in Stuart England, this idealism centering on tobacco would help foster a new economics of imperialism, one that began to displace gold as an imperialist preoccupation in favor of commodities previously understood as trifling.7 But many Elizabethan propagandists of tobacco—drawn to medical and economic rationales for smoking yet pursuing such rationales only confusedly or ironically—were finally less concerned with tobacco's material than with its ideal import. Like the antimaterialists of my previous chapters, these

writers believed that the immediate reward of gold had tricked the Spanish into equating imperial with economic success; tobacco was supposed to dramatize that, on the contrary, something like what we would now call ideology was true power. While the Spanish enslaved themselves to gold, tobacco taught the English to limit their ambitions to nothing—or, at least, to nothing but smoke.

I

Columbus sighted tobacco on his first voyage, but "the first original notice in English of the use of tobacco by the Indians" (Brooks, Tobacco , 1:17-18, 45) does not appear till 1565, in John Sparke's account of Sir John Hawkins's second slaving voyage. "The Floridans when they travel," observes Sparke,

have a kind of herb dried, who with a cane and an earthen cup in the end, with fire, and the dried herbs put together, do suck through the cane the smoke thereof, which smoke satisfieth their hunger, and therewith they live four or five days without meat or drink, and this all the Frenchmen [Jean Ribault's men, about to be massacred by the Spanish] used for this purpose: yet they do hold opinion withal, that it causeth water & phlegm to void from their stomachs. (PN 10:57)

Such a report of tobacco's double, and as Sparke's "yet" signifies, slightly paradoxical power—at once to nourish and to purge—gets reiterated by English writers too many times to bother citing, though when William Harrison (1573) and the elder Hakluyt (1582) acknowledge that tobacco is now being planted in England, they naturally single out not its nutritional but its medicinal virtue as the benefit required by certainly well-to-do buyers: tobacco, they say, eases the rheum.8

Now the rheum—what we call an allergic reaction or the common cold—was enough of a worry in Tudor England to make a remedy for it seem marvelous indeed. Sir Thomas Elyot's Castel of Helth (1541), for instance, claims that "at this present time in the realm of England, there is not any one more annoyance to the health of man's body, than distillations from the head called rheums" (77v). Ever since the Tudor peace, Elyot believes, the disease has become more frequent, the English head more watery, as

the English have increasingly devoted themselves to excess, like "banquetings after supper & drinking much, specially wine a little afore sleep" (80r). Indeed, in Elyot's account the rheum's symptoms—"Wit dull. Much superfluities. Sleep much and deep" (3v)—look just like its causes; one might conclude that the rheum not only mirrors but helps perpetuate the complacence and corruption of manners producing it.

Given this sociological understanding of the disease, however, tobacco seems an unusual choice for a remedy. If it is relatively easy to imagine a physical opposition between tobacco and the rheum, the rheum as cold and moist being driven out by tobacco as hot and dry, it is much less easy to see how an expensive novelty could help do anything but augment the intemperance Elyot decries.9 "A Satyricall Epigram" in Henry Buttes's Dyets Dry Din ner (1599) mocks tobacco—though only its "wanton, and excessive use," a qualification to which I will return—as simply the latest foreign luxury helping to drown the English character: "On English fool: wanton Italianly; / Go Frenchly: Dutchly drink: breath Indianly" (P4r). Later, "Philaretes" in his Work for Chimney-Sweepers (1602) denounces tobacco not only as a foolish toy but as the devil's invention, a fact amply demonstrated, he believes, by the observations of the herbalist Monardes on tobacco's American heritage:

The Indian Priests (who no doubt were instruments of the devil whom they serve) do ever before they answer to questions propounded to them by their Princes, drink of this Tobacco fume, with the vigor and strength whereof, they fall suddenly to the ground, as dead men, remaining so, according to the quantity of the smoke that they had taken. And when the herb had done his work, they revive and wake, giving answers according to the visions and illusions which they saw whilst they were wrapt in that order. (F4r)

(The devil aside, tobacco here even exaggerates the physical symptoms, the dullness and sleepiness, associated with the rheum: the priests fall down "as dead men.") The odd truth about this kind of argument, however, is that Philaretes' is the first full-scale attack on tobacco to be launched in English, some thirty years at the very least after its use in England began.10 Even Monardes himself, in the herbal that proved to be "the most frequently issued book of overseas interest in the Elizabethan period,"11 concludes that

tobacco's superstitious application shows only how "the Devil is a deceiver, and hath the knowledge of the virtue of Herbs" (Joyfull Newes 1:86); by Philaretes' own account "Monardus" is one of the "many excellent & learned men" who "do commend this plant as a thing most excellent and divine" (Work , A3r). What was there about tobacco that enabled it for so long not only to escape the censure one would expect but to receive such lavish praise instead?

One answer is provided by Philaretes' anxiety about his pamphlet's reception. So strong are the voices for tobacco, and so rare the voices against it—"Many excellent Physicians and men of singular learning and practice, together with many gentlemen and some of great accompt, do by their daily use and custom in drinking of Tobacco , give great credit and authority to the same" (A3r)— that Philaretes feels he must embark on a disputation against Authority (citing Plato and Aristotle in his defense) before his tobacco argument can proceed (A4v). But to claim that tobacco prospered because the mighty took it under their wing12 is only to rephrase the question: what enabled tobacco to win such powerful favor? The two most obvious explanations, that tobacco is inherently likable, not to say addictive, and that tobacco's novelty added luster to its intrinsic charm, fail fully to account for the particular circumstances of tobacco's reception in late sixteenth-century England. First, with the help of herbalists like Monardes, tobacco came to be regarded as not just a rheum distiller but an all-round wonder drug; since tobacco was not the only American herb celebrated this way, its own virtues, whatever they may be, would seem to say less about its identification as a cure-all than about its eventual ascendancy over other New World candidates for Panacea, such as sassafras. Second, the English craze for smoking, like the English taste for America in general, developed much later than on the Continent, later even than its introduction to England as a novelty.13 Here the demonstrably false legend about Raleigh's introducing tobacco to England gains a certain credence: just as Raleigh hardly invented the idea of English colonies in America and yet was the first to start one, so we might imagine the most powerful Englishman in 1590 not as tobacco's original proponent but its most persuasive one.14 The legend about Raleigh in fact derives from the 1590s—Buttes says "our English Ulysses , renowned Sir

Walter Raleigh ... hath both far fetcht it [tobacco], and dear bought it" (Dyets , Psr-P6r)—though James himself lends greater authority to the claim:

With the report of a great discovery for a Conquest, some two or three Savage men, were brought in, together with this Savage custom. But the pity is, the poor wild barbarous men died, but that vile barbarous custom is yet alive, yea in fresh vigor: so as it seems a miracle to me, how a custom springing from so vile a ground, and brought in by a father so generally hated, should be welcomed on so slender a warrant. (Counter-blaste , B2r)15

The denunciation makes sure that James's subjects understand tobacco's political significance: for tobacco to be attacked means for Raleigh to have fallen, and at the same time, though only implicitly here, for pathetic, unprofitable Virginia to have been confiscated by the Crown. I would like to turn now to the surviving evidence about Raleigh and tobacco in order to determine the attractions tobacco held for the man who focused England's attention upon it.

II

The first description and commendation of tobacco one can safely associate with Raleigh are the work not of Raleigh himself indeed, Raleigh is for the most part above speaking on the subject— but of his servant Thomas Harriot, in Harriot's Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (1588).16 The purpose of Harriot's tract—to advertise and justify Raleigh's American efforts— helps in an obvious way to account for both Harriot's praise of tobacco there and the many other claims about tobacco's medicinal wonders in general: if one wants to convince potential investors that Virginia "may return you profit and gain" (322), then a miraculous Virginian herb will come in very handy. What is less obvious is the close relation between the specific properties Harriot claims for tobacco and the kinds of economic returns he and writers like him expected America would bring to little England. The historian D. B. Quinn has called what he considers the most important of these expectations the supplementary economy, the complementary economy, and the emigration thesis.17 The first, the supplementary economy, meant the hope "that North America could

produce many of the products which England herself produced but in greater quantities" (Quinn, "Renaissance Influences," 83) and so could bolster and expand the limited homeland. Harriot is thinking this way when he lists potential Virginian commodities such as woad, "a thing of so great vent and use among English Dyers, which cannot be yielded sufficiently in our own country for spare of ground," but which "may be planted in Virginia, there being ground enough" (Report , 335). The second model foresaw the New World supplying the English, as Harriot says, "with most things which heretofore they have been fain to provide, either of strangers or of our enemies" (324). Renaissance writers generally assumed that the same latitude meant the same climate, and the same climate was all one country needed to produce the same commodities as another country; therefore Virginia, as "answerable" in climate "to the Island of Japan, the land of China, Persia, Jury [Jewry], the Islands of Cyprus and Candy [Crete], the South parts of Greece, Italy, and Spain, and of many other notable and famous countries" (383; cf. 325, 336), held out to England the hope that, in Quinn's words, "the English economy would . . . become virtually independent of imports from all but tropical lands" ("Renaissance Influences," 82). The final model, the emigration thesis, Quinn explains this way: "The tendency for population to increase after the mid-century, together with endemic unemployment associated with the decline of certain branches of the cloth trade, impressed—over-impressed—almost all those who thought about it with the idea that there was a surplus population which ought to be exported" (83). John Hawkins, in a prefatory poem to Sir George Peckham's True Reporte (1583), describes the impression more vividly:

But Rome nor Athens nor the rest, were never pestered so,

As England where no room remains, her dwellers to bestow,

But shuffled in such pinching bonds, that very breath doth lack:

And for the want of place they crawl one o'er another's back.

(439)

It is with such hysteria in mind that Harriot extols "the dealing of Sir Walter Raleigh so liberal in large giving and granting land" in Virginia; "(the least that he hath granted hath been five hundred acres to a man only for the adventure of his person)" (Harriot,

Report , 385). In the light of these hypotheses about increased "home" production, freedom from the threat of foreign embargoes, and room in which to "vent" England's surplus, part of Harriot's description of tobacco's powers looks like a synecdoche for America's expected impact on the English body politic as a whole: tobacco, says Harriot, "openeth all the pores & passages of the body" (344), or in Hawkins's terms, lets England breathe.

The easiest way to grasp the economic constraints that tobacco-as-America might be imagined resolving is to think of them all as effects of one master problem—England's limitation to an island, in particular a northern island hemmed in by enemies. In his Defence of Tabacco: With a Friendly Answer to Worke for Chimny-sweepers (1602), Roger Marbecke traces to this source even England's peculiar susceptibility to the rheum: "but for that we are Islanders . . . we are by nature subject, to overmuch moisture, and rheumatic matter" (33).18 Harriot's captain Ralph Lane, on the other hand, writes to Walsingham from Virginia that "the climate is so wholesome, yet somewhat tending to heat, As that we have not had one sick since we entered into the country; but sundry that came sick, are recovered of long diseases especially of Rheums" (Quinn, Roanoke Voyages 1:202). While Marbecke immediately goes on to agree with Elyot that excessive eating and drinking cause rheum also, these factors equally signal the predicament of a country unable to produce for itself, taking too much in—as it were, drowning for want of land.19 With a whole world to themselves, the Indians, remarks Harriot, are moderate eaters, "whereby they avoid sickness. I would to god we would follow their example. For we should be free from many kinds of diseases which we fall into by sumptuous and unseasonable banquets, continually devising new sauces, and provocation of gluttony to satisfy our unsatiable appetite" (438). It is important to remember that in this dietetic case as in the case of the rheum, tobacco's cure is not merely figurative, representing the extra world little England hopes to acquire; tobacco smoke, said Sparke, "satisfieth their hunger," and Harriot classifies tobacco with other "such commodities as Virginia is known to yield for victual and sustenance of man's life, usually fed upon by the natural inhabitants, as also by us during the time of our abode" (Report , 337).

But no matter how convenient for understanding tobacco in re-

lation to England's economic ills, this classification by Harriot actually forces consideration of some problems about Virginian tobacco that I have so far overlooked. If America is to help England by freeing it from the twin dangers of excessive importation and an unexportable surplus, one might have expected to find tobacco listed not only with the native foods that would support a displaced English population but with the "merchantable commodities" (325) that would feed and enrich home also—which is in fact where Harriot places that other panacea "of most rare virtues," sassafras (329).20 Presumably Harriot knows something about the marketability of Virginian tobacco that he doesn't want to say directly, something like the "biting taste" that prevented Englishmen from becoming interested in colonial tobacco until John Rolfe imported Trinidadian seeds to Virginia in 1610-11;21 most of the tobacco Englishmen "drank" before that time was indeed the enemy's—Spain's—so rather than alleviate England's trade woes, tobacco actually exacerbated them.22 Good reason for sticking to tobacco's nutritional value; but the classification as food is problematic in its own way: Harriot never explicitly mentions the hunger-depressant power he could have found out about not only from the Indians, presumably, but also from such written sources as Monardes (Joyfull Newes , 90-91)—to whom, oddly enough, Harriot refers the reader in the case of sassafras, not of tobacco (Report , 329).23 Whatever the real reason for Harriot's enigmatic silence here, he himself wants the reader to know both that his praise of Virginian tobacco has been cut short and that his reticence about it corresponds to his especially high regard for it: "We our selves during the time we were there used to suck it after their manner, as also since our return, & have found many rare and wonderful experiments of the virtues thereof; of which the relation would require a volume by it self." It is a regard the Indians share. "This Uppowoc "—Harriot's preference for the Indian instead of the well-known Spanish name is itself significant—

is of so precious estimation amongst them, that they think their gods are marvelously delighted therewith: Whereupon sometime they make hallowed fires & cast some of the powder therein for a sacrifice: being in a storm upon the waters, to pacify their gods, they cast some up into the air and into the water: so a weir for fish being newly set up, they cast some therein and into the air: also after an escape of danger, they cast some into the air likewise. (345-46)

If I am fight to say that Harriot has some difficulty placing tobacco in his colonial argument, this description of native or "natural" superstition, intended after all as a weak form of argument from authority, allows Harriot the liberty to speak of tobacco as a panacea without having to rationalize the claim in terms either of physiology or of England's peculiar needs.24 Harriot does not use the Indians to show, in other words, that tobacco has some chemical or synecdochal relation to storms, weirs, or danger; according to Harriot, the Indians simply think that their gods like tobacco: one casts it on things, and things work.

Yet a more common colonial logic, more common even in Harriot's own tract, makes citing Indians as any kind of authority on value look strange. For the most salient fact about savages is that they always hold the wrong thing in "precious estimation"—not gold, for instance, but trifles. One could find Harriot's version of the first confrontation between Americans and Europeans in innumerable travel books:

As soon as they saw us [they] began to make a great and horrible cry, as people which never before had seen men appareled like us, and came a way making out cries like wild beasts or men out of their wits. But being gently called back, we offered them of our wares, as glasses, knives, babies [i.e., dolls], and other trifles, which we thought they delighted in. So they stood still, and perceiving our Good will and courtesy came fawning upon us, and bade us welcome. (Quinn, Roanoke Voyages 1:414)

When Harriot speaks elsewhere of the Indians' powers of estimation, it is only copper "which they much esteem" (441), "which they esteem more than gold or silver" (425);25 in other words, they "do esteem our trifles before things of greater value" (Harriot, Report , 371). While such notices of Indian misprision are meant no doubt to tickle Harriot's readers, and to demonstrate how cheaply Indian favor can be bought,26 the savage love of trifles speaks directly to England's fears, once again, about its own extravagant trading habits. If, as I explained in my previous chapter, English economists could consider their European trade a delusion, the foolish English venting the solid good of bullion in exchange for mere pestering trifles, the still more foolish American savage represented the hope of turning passive victimization into active victimizing—of "buying for toys the wealth of other lands."27

The only catch in Harriot's case is that his credulous Indians don't have any gold; his prefatory letter warns the understanding reader to discount "as trifles that are not worthy of wise men to be thought upon" (Report , 324) the ill reports of such former colonists who "after gold and silver was not so soon found, as it was by them looked for, had little or no care of any other thing but to pamper their bellies" (323). In light of these disaffected gold hunters, with whom Harriot might reasonably expect a very large proportion of his audience to sympathize, Harriot's praise of Indian moderation takes on a colonial significance: if only the English could regard America as the Indians do, and learn to live in America as the Indians do, "free from all care of heaping up Riches for their posterity, content with their state, and living friendly together of those things which god of his bounty hath given unto them" (435). Once again, in the displacement of gold as a measure of value, Indian tastes assume a kind of authority.28 Looking back on Harriot's interest in their "precious estimation" of tobacco, one might say that, for Harriot, tobacco supplies the lack of the precious metal; indeed, when he insists that a full relation of tobacco's virtues "would require a volume by itself," as if tobacco were a New World all its own, still awaiting discovery, he builds into tobacco not only gold's value but its very absence.29

It is a substitution that tobacco's critics later found the English people all too willing to make. Not only had a lack of Indian gold defeated expectations of happy returns from America: somehow even savages had managed to palm off a trifle on the ever eager English consumer. John Aubrey's life of Raleigh (c. 1669-1696) records how, near the turn of the century, the exchange of a trifle for a precious metal was quite literal: tobacco "was sold then for its weight in silver. I have heard some of our old yeoman neighbors say, that when they went to Malmesbury or Chippenham Market, they culled out their best shillings to lay in the scales against the tobacco" (quoted in Brooks, Tobacco 1:50). Thomas Campion (1619) later complains that such skewed powers of estimation have yielded the Spaniards profit:

Aurum nauta suis Hispanus vectat ab Indis,

Et longas queritur se subijsse vias.

Maius iter portus ad eosdem suscipit Anglus,

Ut referat fumos, nuda Tobacco, tuos:

Copia detonsis quos vendit Ibera Britannis,

Per fumos ad se vellera cal'da trahens.

(The Spanish raider carries gold from his Indies and laments that he has gone on long journeys. The Englishman undertakes a longer way to the same parts so that he can bring back your smoke, unadorned Tobacco, which Spanish wealth sells, by this smoke stripping and drawing to itself the hides from the Britons.)30

To its critics, tobacco even seemed to clarify the old fears about England trading its solid commodities for nothing by dramatizing the exchange in a way never before possible: whenever an Englishman lit his pipe,31 he could seem to demonstrate unequivocally how "the Treasure of this land is vented for smoke."32

Yet a well-known anecdote about Raleigh first reported by James Howell (1650) shows how the substitution of gold for smoke could work in an Englishman's favor:

But if one would try a pretty conclusion how much smoke there is in a pound of Tobacco, the ashes will tell him, for let a pound be exactly weighed, and the ashes kept charily and weigh'd afterwards, what wants of a pound weight in the ashes cannot be denied to have been smoke, which evaporated into air; I have been told that Sir Walter Raleigh won a wager of Queen Elizabeth upon this nicety. (Quoted in Dickson, Panacea , 172)

In another version of the anecdote the queen adds in paying, "many laborers in the fire she had heard of who turned their gold into smoke, but Raleigh was the first who had turned smoke into gold" (Dickson, Panacea , 172).33 The story compactly illustrates a great deal of Raleigh's relation to the queen—the carefully staged destruction of his property, like his muddied cloak or his melodramatically desperate posturings, bringing him greater wealth. But this manner of enriching oneself via the New World and its products is crucially different from the colonial models and tobacco uses I have specified: unlike a chemical or alchemical transformation of the English body or body politic, Raleigh's tobacco simply wins him a bet; the gold comes neither from the New World nor its inhaled representative but from Elizabeth. There seems nothing about tobacco's place in the story, in other words, that some other inflammable object might not fill—the operative term is, after all, smoke.

But perhaps tobacco's replaceability here is what helps make its

appearance in the story, and in the story of Raleigh's life, so inevitable: for the story must be about Raleigh, not tobacco, and it must show that what Raleigh does to tobacco, turning smoke to gold, is only what he has done to himself—as Stephen Greenblatt reminds us about Raleigh in his prime, he was "perhaps the supreme example in England of a gentleman not born but fashioned" (Renaissance Self-Fashioning , 285-86 n. 29). Contemporaries did not miss the correspondence, fatuously dramatized by Raleigh before his execution, between Raleigh's smoking and his pride, his aloofness; whether or not Raleigh smoked at the execution of his rival Essex also, the story sounded so plausible and epitomizing that, at his own execution, Raleigh was forced publicly to deny it.34 Others quickly adopted the flourish a pipe could bring them. In his mock travelogue Mundus Alter et Idem (1605),35 Joseph Hall "discovers" Raleigh and tobacco in Moronia Felix, or, in Hall's own gloss, the "land of braggarts, or of conceited folly" (93). Like Raleigh, everyone in Moronia Felix pretends to noble birth, though their claims, like their sumptuous buildings, "are exceedingly flimsy, and whatever their external splendor promises, on the interior they are sordid beyond measure" (94). Lacking funds and good sense, "most of the inhabitants feed neither on bread nor on food but on the fume" of their own vanity and of tobacco:36 "and while their nostrils exhale smoke high in the air, their kitchens have passed completely out of use" (96). Joseph Beaumont (c. 1640s) will later denounce such high estimations of inanity in terms recalling Raleigh's wager: "Was ever Nothing sold by weight till now, / Or smoke put in the Scale?" (Minor Poems , 71). And indeed, the wager anecdote captures very well not only the insubstantiality of Raleigh's position as Hall sees it—"without a power-base of any kind, . . . Raleigh was totally dependent upon the queen" (Greenblatt, Ralegh , 56)—but also Raleigh's irritating or enviable ability to capitalize on that insubstantiality, to give it weight, to turn the smoke of his own bravura, and of Elizabeth's favor, to account.

If tobacco figures in the anecdote, then, as little more than the personal trademark of the queen's alchemist, Raleigh's America similarly distances itself from the national hypotheses about New World benefits that I have so far outlined. Even the primary advocate of such hypotheses, Richard Hakluyt, appears to abandon

them whenever he helps Raleigh articulate his self-serving vision of America. In dedicating to Raleigh the newly edited De Orbe Novo of Peter Martyr, for example, Hakluyt (1587) praises Raleigh's

letters from Court in which you freely swore that no terrors, no personal losses or misfortunes could or would ever tear you from the sweet embraces of your own Virginia, that fairest of nymphs— though to many insufficiently well known,—whom our most generous sovereign has given you to be your bride[.] If you persevere only a little longer in your constancy, your bride will shortly bring forth new and most abundant offspring, such as will delight you and yours, and cover with disgrace and shame those who have so often dared rashly and impudently to charge her with barrenness. For who has the just title to attach such a stigma to your Elizabeth's Virginia, when no one has yet probed the depths of her hidden resources and wealth, or her beauty hitherto concealed from our sight? Let them go where they deserve, foolish drones, mindful only of their bellies and gullets, who fresh from that place, like those whom Moses sent to spy out the promised land flowing with milk and honey, have treacherously published ill reports about it.37

The jolting reference to Virginia's imputed barrenness demands not only that the possibly vague or nominal comparison between Elizabeth and Virginia be taken seriously but also that the analogy be extended into what one might consider the most dangerous territory. Yet in similarly dwelling on the possible throwaway about Raleigh's "sweet embraces" with his "bride," the lavish sexual imagery that follows, the hidden beauty and the probe-able depths, shows that taking liberties is precisely Hakluyt's point: the racy language is itself part of the dalliance between Elizabeth and Raleigh that Virginia makes possible.38 Like tobacco smoke, Virginia's whole beauty here in relation to Raleigh lies in its essential malleability, the ease with which it stands for a marriage, and the fruits of a marriage, otherwise impossible. But it is crucial to see that in allegorizing Virginia as a substitute Elizabeth, the passage drives toward claiming what Virginia's critics claim also, that Virginia has no attractions per se. And indeed Elizabeth will allow Raleigh to probe Virginia only if he stays at Court—near Elizabeth, certainly, but far from the vicarious deflowering.39

I do not mean to argue, however, that Raleigh's erotic American allegory is entirely at odds with other more nationally oriented New World views, or that Hakluyt himself, the writer here, does not also desire and enjoy this vision, as others would desire and

enjoy Raleigh's smoking. After all, Elizabeth's virginity, or more negatively her barrenness, betokened national concerns not merely by analogy: since Elizabeth's foreign suitors represented the possibility of international alliances, since her favor meant money and power, and since her offspring, it was hoped, would ensure a peaceful succession, the queen's maidenhead would seem more than merely symbolic of both national isolation and the "want of place" at Court. By the same token, the logic of surrogacy that idealizes Raleigh's Virgin-ian colonialism would be useful not only to other colonialists trying to justify leaving England but to other courtiers trying to justify having interests besides Elizabeth: thrown into disgrace with the queen as a result of his actual marriage, the courtier Robert Cary, for instance, successfully redeemed himself by telling Elizabeth that "she herself was the fault of my marriage, and that if she had but graced me with the least of her favors, I had never left her nor her Court" (Nichols, Progresses 3:216).

In fact, as Hakluyt's allegory continues beyond the bridal motif, it demonstrates how the particular reduction of Virginia to a metaphor for an available queen only isolates a hidden tendency common to other more strictly economic colonial theorizing, a tendency to understand Virginia as nothing but a substitution, rather than a different place and, possibly, a different home. Hakluyt's comparison of the English people to the Jews highlights the problem of English attachment to England's island by ineptly running counter to that attachment: the switch from Raleigh and Elizabeth to Moses seems to leave Elizabeth behind and Raleigh too, even if he is seen as Moses, for Moses, of course, never entered "the promised land"; but then Virginia as the promised land neither complements, supplements, nor relieves England but leaves the island, like the wilderness, behind altogether. In brief, the difference between Elizabeth and Moses in Hakluyt's allegory seems to be the difference between regarding England or Virginia as home. Yet Hakluyt can hardly be intending to suggest that England be abandoned. In calling Virginia the promised land he clearly over-compensates for Virginia's felt lack of intrinsic merit, a lack he at other times even helps, oddly enough, to publicize: the Principall Navigations (1589) records the verdict on Virginia of one more Raleigh underling, Ralph Lane again, who affirms "that the discov-

ery of a good mine, by the goodness of God, or a passage to the Southsea, or someway to it, and nothing else can bring this country in request to be inhabited by our nation" (Quinn, Roanoke Voyages 1:273). On the other hand, Hakluyt can hardly mean that Englishmen should never settle Virginia. When, in his address to Raleigh, Hakluyt deplores, as Harriot will (Report , 323), those ex-colonists "mindful only of their bellies and gullets," it is the profiteering English view—that gold in hand is the only thing worth leaving home and probing Virginia's depths for—that he means, again like Harriot, to condemn. Hakluyt wants to say that Virginia supplies a "milk and honey" that satisfies something more than bellies, something like Raleigh's impossible desire for Elizabeth, which hopes to "occupy" both Elizabeth and Virginia at once, though in a far from literal way. A manna made "of conceited folly," of air—yet an air the Elizabethans thought substantial enough to "drink"—tobacco helps represent both the expansionist desire and its chimerical satisfaction.40 Harriot's ambiguous position about tobacco/uppowoc, classifying it as nourishment to be exploited "there" while describing its use "here," begins to make more sense: requiring a volume all its own, tobacco helps suspend the question of Englishmen's true home, as if the metaphorical identification between England and Virginia were as good as, indeed better than, a soldier settlement.

III

Tobacco enters The Faerie Queene bearing this question of mediation, posed once again in terms of Raleigh's desire for Elizabeth. The dedicatory letter to Raleigh and the proem to The Faerie Queene's third book identify Belphoebe in two ways. First, she is said to represent one aspect, or "person," of Elizabeth: "a most vertuous and beautiful Lady" as distinguished from "a most royal Queen or Empress" (V 2:168); or Elizabeth's "rare chastitee" as distinguished from "her rule" (FQ 3.proem.5). Second, Spenser claims to have fashioned her after Raleigh's "own excellent conceit of Cynthia" (V 1:168). By removing the impediment of Elizabeth's high station and presenting an Elizabeth after Raleigh's own conceit, Spenser's Belphoebe moves Elizabeth closer to Raleigh's desires in much the way Hakluyt's Virginian bride does. Tobacco

strengthens the analogy to Hakluyt. With it, Belphoebe heals Timias's spear wound41 but inflicts a love wound she cannot bring herself to cure: "But that sweet Cordiall, which can restore / A love-sick hart, she did to him envy" (FQ 3.5.50). This more desirable cordial happens to be "that dainty Rose" (51), "her fresh flowring Maidenhead" (54). Though Spenser's pathos here hardly figures in Hakluyt's passage (nor, for that matter, in Spenser's source),42 the general allegorical point is basically the same: Raleigh is dying for Elizabeth's Rose, yet she grants him another flower, "divine Tobacco," as at once a demurral and a compensation; while the pastoral landscape that supports two classical herbs and an American one, and that presents the choice between them as almost indifferent, seems to show Spenser ignoring practical distances and distinctions (as far as he might safely do so) in favor of a less formidable gap, between not classes but states of mind— Timias's "mean estate" (44) and Belphoebe's "high desert " (45; my emphasis).43

This daring treatment of Raleigh's love for Elizabeth represents a step forward, or at least a new installment, in a debate about Elizabeth that Spenser had entered with the publication of The Shepheardes Calender a decade earlier. As my previous chapters argue, The Shepheardes Calender manifests Spenser's resistance to an increasingly popular view of Elizabeth that celebrated the Virgin Queen for keeping the English island separate and pure, an "Elizium." Faced with the problem of denouncing insularism as a political ideal while retaining Elizabeth as one, Spenser transforms Eliza's Elizium into an ideal that his alter ego, Colin, once celebrated but has now, for purely private and natural reasons, forsworn: what alienates Colin from pastoral complacency is, ostensibly, only his unrequited love for the shepherd-hating Rosalind. Yet the "November" eclogue, in which Colin returns as singer, underscores the political ramifications of his new melancholy by combining Eliza as pastoral genius and Rosalind as unattainable beloved in the figure of the dead Dido; Colin forsakes complacency about pastoral England to such a degree that he now longs only for the renovated "Elisian fieldes" ("November," 179) Dido seeks in heaven. If we take the epic reference in "Dido" seriously, however (and this is not the first such reference in the Calender ), her death would also seem to mean, mysteriously enough, a gain for

empire; the Calender leaves us wondering how Colin, the self-exiled Englishman, will find a compromise "England" between pastoral and the contemptus mundi that pastoral desire ultimately generates.

Compared to this esoteric argument about sexual frustration and Elizabeth, the Faerie Queene episode is quite striking in its directness, thanks to an even more striking development at Court: the rise to power and favor of "Colin's" exact contemporary and fellow adventurer in Ireland, Raleigh, has made it easier for Spenser to represent the unobtainable beloved as Elizabeth herself. Less obvious is the way the Timias and Belphoebe episode rewrites another feature of Colin's plight. In "December" Colin laments the fact that his pastoral lore cannot alleviate his love-woe:

But ah unwise and witlesse Colin cloute ,

That kydst the hidden kinds of many a wede:

Yet kydst not ene to cure thy sore hart roote,

Whose ranckling wound as yet does rifelye bleede.

(91-94)

This irony about herbal cures reflects the increasing transformation of Colin's frustrated desire into contemptus mundi ; the "wede" becomes a synecdoche both for mere worldliness and for the pastoral "flowers" or poetry proportioned to that worldliness.44 But when George Peele in his Araygnement of Paris appears to imitate Spenser, here in reference to Peele's own Colin—"And whether wends yon thriveless swain, like to the stricken deer. / Seeks he Dicta-mum for his wound within our forest here" (565-66)45 —he pointedly separates Colin's frutration from the issue of Elizabeth's virginity. According to Peele, Colin despairs and finally dies because he is too worldly himself, too absorbed in his beloved to recognize the better, otherworldly worldliness embodied in the virgin Eliza, "in terris unam . . . Divam" (1230). Responding to such an interpretation of Colin's alienation, it seems, Spenser in the Timias and Belphoebe episode makes Eliza herself the purveyor of inadequate herb cures and therefore of the argument to despair.46

Spenser agrees with Peele, then, that the pastoral lover is too worldly, but he adds that the pastoral beloved is equally so: absorbing themselves in the disposition of Elizabeth's actual maidenhead and therefore reducing Elizabeth to the private person Bel-

phoebe, Raleigh and Elizabeth, argues Spenser, debase the potentiality of a queen who, rightly understood, is as little a mere body as possible, a "Mirrour of grace and Majestie divine" (FQ 1.proem.4). Belphoebe treats her rose as if it were literal: she hides it in foul weather but in fair weather allows it to be "dispred" (3.5.51). The narrator, however, makes maidenheads sound figurative: he says they reside "in gentle Ladies brest" (52), and advises his female readers that such flowers should even "crowne" their "heades" (53). As for Timias, his response to Belphoebe does not, after all, differ much from the earlier reaction of the literalizing Braggadocchio, who

fild with delight

Of her sweet words, that all his sence dismaid,

And with her wondrous beautie ravisht quight,

Gan burne in filthy lust, and leaping light,

Thought in his bastard armes her to embrace.

(2.3.42)

Though nobler than "the baser wit, whose idle thoughts alway / Are wont to cleave unto the lowly clay," the languishing Timias nevertheless fails to aspire as the "brave sprite" should "to all high desert and honour" (3.5.1). If, then, Timias's degenerate precursor Braggadocchio helps reveal his own despair to be only a more genteel version of lust, Timias's master Arthur adumbrates the higher response to Elizabeth: he loves the queen as not the private Belphoebe but the public Gloriana. What's more, Arthur experiences less of Gloriana's physicality than either Braggadocchio or Timias does of Belphoebe's, for he meets the Fairy Queen only in a dream (1.9.12-15). Yet this dream is more than a fantasy. Determinedly ambiguous—material enough to have "pressed" the grass beside Arthur, though immaterial enough to vanish Arthur's dream woman tantalizes him with just the right blend of corporeal and incorporeal inducements, of hope and despair, to keep him earthbound and yet always on the go.

Ultimately, however, not even Arthur's love proves fully separable from Braggadocchio's, for if Arthur seems less desperate than his squire, that is because he has no physically present beloved about whose body he can despair. In other words, like the reader of The Faerie Queene whose complacence Spenser expects to

shake by "vaunt[ing]" of a fairyland Spenser "no where show[s]" (2.proem. 1), Arthur escapes becoming absorbed in the queen's material person only because he "no where can her find" (2.9.7): it is the immateriality, the otherworldliness, the utopicality of both Fairyland and fairy queen that are supposed to keep both Arthur and the reader questing. By book 3, however, Arthur's inability to catch the fleeing Florimell has so aggravated his frustration about not reaching Gloriana that he begins to ride "with heavie looke and lumpish pace, that plaine / In him bewraid great grudge and maltalent" (3.4.61). The mere promise of some future consummation is no longer enough for him, and so it is that the next canto provides a more materialist version of Elizabeth—Belphoebe—in order to show us how catching her has its own problems.47

Raleigh himself articulates the pathos surrounding Elizabeth's admirers in these episodes when, in a portion of his Ocean to Scinthia (c. 1592) reminiscent of Wyatt's Tagus poem, he laments how his love for Elizabeth at once inspires and subverts his imperialist ambition:

The honor of her love, Love still devising,

Wounding my mind with contrary conceit

Transferred itself sometimes to her aspiring,

Sometime the trumpet of her thoughts' retreat;

To seek new worlds, for gold, for praise, for glory,

To try desire, to try love severed far,

When I was gone she sent out her memory

More strong than were ten thousand ships of war,

To call me back, to leave great honors' thought,

To leave my friends, my fortune, my attempt,

To leave the purpose I so long had sought

And hold both cares and comforts in contempt. (57-68)48

But the Timias and Belphoebe canto does more than reproduce Raleigh's "contrary" desire: it also offers a cure, suggested when Belphoebe first appeared in the poem. Upon Belphoebe's entrance in book 2, the narrator himself anticipates Braggadocchio's lustful absorption in her by devoting the longest blazon in the poem to her body (2.3.21-31); yet at the same time he stresses the saving insubstantiality of poetical leering when he adds, "So faire, and thousand thousand time more faire / She seemd, when she presented was to sight" (26). A climactic feature of every proem to

The Faerie Queene , this issue of Spenser's inadequacy at representing Elizabeth appears in narrative form later in book 2 when Arthur stops to admire the picture of the Fairy Queen on the shield of the knight of Temperance, Sir Guyon, and Guyon assures him that

if in that picture dead

Such life ye read, and vertue in vain shew,

What mote ye weene, if the trew lively-head

Of that most glorious visage ye did vew?

But if the beautie of her mind ye knew,

That is her bountie, and imperiall powre,

Thousand times fairer then her mortall hew,

O how great wonder would your thoughts devoure,

And infinite desire into your spirite poure!

(2.9.3)

An art figured as insufficient, "dead," to its referent turns out to mimic, and therefore properly underscore, the ontological insufficiency of Elizabeth's body to her mind.

Thus, when Spenser in the proem to book 3 ostensibly laments his ability only to "shadow" (3) Elizabeth, and imagines the queen possibly "covet[ing]" to see herself "pictured" instead in the "lively colours, and right hew" (4) of Raleigh's own poetry, he already begins the critique of "Cynthian" Belphoebe that will appear later in the same book. In fact, Spenser's depiction of Raleigh's "lively" art as lulling Spenser's senses "in slomber of delight" also recalls the critique of such art that had been developed in the preceding canto, where the artful Bower of Bliss proved so sufficient to nature as to be more prodigal in its worldliness than nature itself.49 It is the pastoral art of "respondence" familiar from "Aprill" and the Error episode, in which "birdes, voyces, instruments, windes, waters, all agree" (2.12.70); and, when concerned with representing a woman in particular, it leads not to her enhancement but to her diminution, her reduction to and ultimately from her body, as when the magus Busirane forms the "characters of his art" with the "living bloud" (3.12.31) of Belphoebe's sister Amoret.

If Spenser argues, then, that his conspicuously inadequate or trifling representations of the queen are more faithful and consequently less damaging to Elizabeth's true beauty than Raleigh's

iconic verse, he does not go so far as to insist that his own poetry is wholly insubstantial; rather, he depicts it as sharing the ambiguous status that Arthur accords his dream of Gloriana. When the muse Polyhymnia in The Teares of the Muses (1591), for instance, celebrates that "true Pandora of all heavenly graces, / Divine Elisa " (578-79), she also prays that "divinest wits" will "etemize" Elizabeth with "their heavenlie writs " (581-82; my emphasis). Polyhymnia stresses, in other words, not just the spiritual import of a truly Elizabethan poetry but its materiality, the actual writings or documents that Elizabeth's poets will produce; and these writings even surpass the bodies of Elizabeth and Gloriana as bodies in their ability to make lastingly present, to "eternize," what a normal body cannot. Yet how can one distinguish such acceptable poetic materiality from the worldly substantiality Spenser repudiates? Since the "writs" Polyhymnia describes are not Edenic, as in the Bower of Bliss (FQ 2.12.52), but "heavenlie," Spenser apparently believes that it is the oxymoronic "character" of this poetry, the allegorical disparity between its signs and its referents, that both saves it from mere worldliness and qualifies it to represent the equally oxymoronic divinity of the queen.50

In the Timias and Belphoebe episode, the "divine" similitude for a queenly "Mayd full of divinities" (3.5.34) is conceived so materially as to be called a flower, or in Spenser's more oxymoronic formulation, a "soveraigne weede" (33). But this poetical herb also has specific political implications. If Raleigh's romantic attachment to the queen enables a more directly critical treatment of her "insular" virginity in this episode than Spenser could muster in The Shepheardes Calender , another aspect of Raleigh's ambition—as unavailable to Spenser at the writing of The Shepheardes Calender as the royal love affair with Raleigh—has allowed Spenser to extend his critique. For the worldly herb that allegorically figures the limitations of worldliness can now be the flower of a pastoral transcending the English island and yet still English and earthly—Virginian tobacco. Shortsighted about their relationship, Timias and Belphoebe fail to recognize that the episode's conspicuously inadequate correlative to Belphoebe's maidenhead can mean more than its present materiality, can signify Virginia as both an other-worldly reflection of "the heavenly Mayd" (3.5.43) and an actual substantiation of her "imperiall powre." What "divine tobacco," a

posy of poesy, allegorizes, in short, is the possibility of Elizabethan expansion beyond the apparent material limitations of both Elizabeth and England the mystery of a royal Virgin bearing "fruit."

IV

The surprising notoriety of "divine" as an epithet for tobacco would seem to suggest, however, that Spenser's readers, and perhaps Spenser himself, see more in tobacco's divinity than a subtly ironic literary-imperialist argument concerning the inadequacy of pastoral to desire. No doubt the mere association of the queen with this epithet helped popularize it, especially since tobacco requires divinity in the episode so as to render it more commensurable, again, with "heavenly" Elizabeth. But if the divinity shared by Elizabeth and Virginia in Hakluyt looks mysterious, what sense can the assertion of tobacco's comparable divinity make? Tobacco, it seems, must already have appeared a material expression of spirituality for it to have conveyed, or seem to have conveyed, an abstruse vision of Elizabethan otherworldliness so successfully; but why? In part both Spenser and his subsequent imitators may echo a Continental tradition about tobacco's divinity;51 but then what made Continental writers adopt this view? The influence of Indian "estimation" seems once again difficult to deny, as James demanded his subjects to consider:

Shall we . . . abase our selves so far, as to imitate these beastly Indians , slaves to the Spaniards , refuse to the world, and as yet aliens from the holy Covenant of God? Why do we not as well imitate them in walking naked as they do? in preferring glasses, feathers, and such toys, to gold and precious stones, as they do? yea why do we not deny God and adore the Devil, as they do? (Counter-blaste B2r)52

If the charges against Marlowe, Raleigh, and Raleigh's followers may be believed, the king's hysteria was not entirely unwarranted: the infamous snitcher Richard Baines (1593) reported Marlowe's assertion "that if Christ would have instituted the sacrament with more ceremonial Reverence it would have been had in more admiration, that it would have been much better administered in a Tobacco pipe"; and a lieutenant of Raleigh's was allegedly seen to "tear two Leaves out of a Bible to dry Tobacco on" (quoted in Shir-

ley, Harriot , 182-83, 192). Philaretes comments, "Our wit-worn gallants, with the scent of thee, / Sent for the Devil and his company." To the tobacco hater, tobacco does not complement English values, it inverts them, hell for heaven; Philaretes too believes the comparison with Elizabeth explains tobacco, though not as her surrogate, a bride, but as her travesty, a whore: "O I would whip the quean with rods of steel, / That ever after she my jerks should feel" (Work , Br).53

The problem is the same one posed by Elyot's analysis of the rheum—how can a far-fetched luxury associated with the depths of superstition come to any good?—and yet some of tobacco's advocates not only excused tobacco but exalted it as England's "divine" savior from just that decadence and superstition it would seem to exacerbate. A poem attributed in Essex's lifetime to Essex offers the pathos Spenser associates with tobacco as tobacco's justification. The poem, "The Poor Laboring Bee" (1598),54 laments Essex's singular and undeserved bad luck: "Of all the swarm, I only could not thrive, / yet brought I wax and Honey to the hive." Even before any mention of tobacco Essex invokes the terms of Timias's unhappiness—the other bees "suck" Elizabeth's flowers, the rose and eglantines—but the poem's conclusion makes Essex's debt to Spenser unmistakable: "If this I cannot have; as helpless bee, / Wished Tobacco, I will fly to thee" (the Egerton MS of the poem reads "Witching Tobacco," which moves the poem closer to Philaretes' pessimism about the exchange). Yet tobacco's cure works not by compensating for but by dramatizing and generalizing Essex's disappointment as the fate of all worldly desires:

What though thou dye'st my lungs in deepest black.

A Mourning habit, suits a sable heart.

What though thy fumes sound memory do crack,

forgetfulness is fittest for my smart.

O sacred fume, let it be Carv'd in oak,

that words, Hopes, wit, and all the world are smoke.

Calvin says that "not only the learned do know, but also the common people have no Proverb more common than this, that man's life is like a smoke."55 And so Essex transforms Philaretes' attack on tobacco as "smoking vanity" (Work , Br) into the very basis of tobacco's claim to sacredness. Tobacco's insubstantiality, that is, leads Essex to a sublime view of the world as itself insubstantial,

to contemptus mundi ;56 while in the same way the otherwise humiliating exchange of solid good for smoke—as a character in Dekker has it, "Tobacco, which mounts into th'air, and proves nothing but one thing . . . that he is an ass that melts so much money in smoke"57 here proves the taste for tobacco less delusory than the love of precious metals, "sweet dreams of gold."

Henry Buttes similarly turns tobacco's deficits to spiritual advantage, though more optimistically than Essex. The title page of Dyets Dry Dinner oddly takes for granted that a meal should be "served in after the order of Time universal," or to put it another way, that the ontogeny of one's banquet should recapitulate the phylogeny of human culture. Thus the meal begins with the food "Adam robbed [from] God's Orchard" (A7v)—fruit—then proceeds through dishes consequent on new developments in "humane invention," until our itch for "voluptuous delight" (A8r) leads us to that most odious of luxuries, sauces. It is at this point, as in Elyot, that the rheum arrives, the bodily counterpart to a superfluity, a running over, on two oddly correspondent scales of time, of a meal and of a human history that have both lasted too long:

Thus proceeded we by degrees, from simplicity and necessity, to variety and plenty, ending in luxury and superfluity. So that at last our bodies by surfeeding, being overflown and drowned (as it were) in a surpleurisy or deluge of a superfluous raw humor (commonly called Rheum) we were to be annealed (like new dampish Ovens, or old dwelling houses that have stood long desolate). Hence it is that we perfume and air our bodies with Tobacco smoke (by drying) preserving them from putrefaction. (A8v)

Yet of course, as the phylogenetic scheme of the meal demands that we see, tobacco is the ultimate superfluity, and Buttes himself later spells out the rheumlike "hurt" tobacco can do: it "mortifieth and benumbeth: causeth drowsiness: troubleth & dulleth the senses: makes (as it were) drunk: dangerous in meal time" (P5v). Presumably his pharmacology is, then, homeopathic: a little more excess somehow eradicates excess altogether. But the moral is quite different from that of Essex, who prizes tobacco for dramatizing the true nature of all "voluptuous delight." Buttes's homeopathy cuts two ways. Fire to rheum's water, tobacco as after-dinner mint replaces the grand conclusion to our history, the

conflagration that follows our punishment by deluge;58 in other words, as at once the latest luxury and earliest apocalypse, tobacco homeopathically cures, in Buttes's mind, both our decadence and God's judgment upon it.

Though one is tempted to dismiss this conclusion, like so many other Elizabethan arguments about tobacco, as a particularly eccentric joke, Buttes's theology seems basically the same as Philaretes', who believes that the English are somehow in a peculiarly good position to mediate between worldly delights and a divine contempt for them. Philaretes' problem with tobacco is that it is too grossly of the world its priestly user "dead sleeping falls, / Flat on the ground"—and so threatens to undo England's compromise between contemptus and carnality, heaven and earth: "But hence thou Pagan Idol: tawny weed, / Come not with-in"—not our Christian but—"our Fairie Coasts to feed" (Work , Br; my emphasis). Buttes defends tobacco's role in preserving this compromise by sidestepping overt theology and invoking instead what he considers commonsense physiology. According to Borde's Breviary of Helthe , for instance, rheum causes sleepiness by producing "great gravidity in the head," by weighing the head down ("The Extravagants," not by Borde, 18v). John Trevisa says it clogs one's "spirit":

For sometime rheumatic humors cometh to the spiritual parties & stop the ways of the spirit and be in point to stuff the body. / Then cometh dryness or dry medicines. & worketh & destroyeth such humors. & openeth the ways of the spirit / & so the body that is as it were dead hath living.59

By this account hot and dry tobacco would seem, in other words, to oppose grossness; and so Marbecke argues even against Philaretes' interpretation of Monardes' report on tobacco's superstitious usage:

For take but Monardus his own tale: and by him it should seem; that in the taking of Tobacco : they [the priests] were drawn up: and separated from all gross, and earthly cogitations, and as it were carried up to a more pure and clear region, of fine conceits & actions of the mind, in so much, as they were able thereby to see visions, as you say: & able likewise to make wise & sharp answers, much like as those men are wont to do, who being cast into trances, and ecstasies, as we are wont to call it, have the power and gift thereby, to see more wonders, and high mystical matters, then all they can do,

whose brains, & cogitations, are oppressed with the thick and foggy vapors, of gross, and earthly substances. Marry, if in their trances, & sudden fallings, they had become nasty, & beastly fellows: or had in most loathsome manner, fallen a-spewing, and vomiting, as drunkards are wont to do: then indeed it might well have been counted a devilish matter: and been worthy reprehension. But being used to clear the brains, and thereby making the mind more able, to come to herself, and the better to exercise her heavenly gifts, and virtues; me think, as I have said, I see more cause why we should think it to be a rare gift imparted unto man, by the goodness of God, than to be any invention of the devil. (Defence , 58-59)

Now smoke for substance is a godly exchange: the mind comes to herself, though still clogged and hamstrung by the body; carried up in ecstasies to a purer and clearer region, though still on earth.60

Freeing the English from the body's limitations as well as from England's small, rheumatic island, tobacco removes a secondary curb on the English mind—particularly, on English poetry. In light of the Renaissance theory that warmer climates are more conducive to mind than colder ones,61 Harriot's list of the warm countries, like Greece and Italy, to which Virginia's climate is similar takes on a new significance: Virginia can be understood as opening for England not merely economic but intellectual and poetic vistas, vistas to which tobacco's own heat contributes. But to see Virginia's and tobacco's advantages in this light is to render finally untenable the reduction of tobacco's powers merely to synecdoches for Virginia's. In order to warm up the English the Virginian way, one must ship them many miles and latitudes hence; yet tobacco brings to the English Virginia's heat—what Beaumont will call the "Indian sun"—without their having to leave the comforts of home. But then all of tobacco's benefits, like its after-dinner annealing in Buttes, are immediate, and Virginia's only anticipated; insofar as those benefits are taken seriously, tobacco does not merely stand for the New World but stands in for it by transforming England into a new world all its own.62

Of course that is just the point tobacco's critics make also: Hall's name for Raleigh in the tobacco passage of Mundus Alter et Idem , Topia-Warallador, buries Raleigh in the name of the Indian cacique Raleigh met in Guiana, Topi-Wari, and the Spanish word for discoverer, hallador , so as to suggest how an Englishman's interest in America can un-English him. Richard Brathwait (1617), scandal-

ized by the fact that the sign used to advertise a tobacco shop should be a black man smoking, called tobacconists "English Moors " (see figure 6).63 The physiological side to this argument is that tobacco smoke makes an Englishman as black on the inside (inside the body, inside England's bounds) as the Indian is on the outside (on his body's outside, outside England).64 But to the tobacco advocate smoke is precisely the key for proving that tobacco converts the New World into a disposable remedy—and now even Raleigh's self-aggrandizing bet, in which tobacco's smoke becomes his substance, seems to have its national correlative: tobacco purges the pent-up body, opens its pores, warms its brain, and helps it breathe, by itself going up in smoke. Opposing Philaretes' fear that tobacco will turn the English body into a torrid zone, Marbecke even denies that smoke has the power seriously to alter anything:

The taking thereof, especially in fume, (which as your self granteth, hath very small force to work any great matter upon our bodies ) can cause no such fiery, and extreme heat in the body, as is by you supposed, but rather, if it do give any heat, yet that heat is rather a familiar, and a pleasing heat, than an immoderate, extraordinary, and an aguish distemperature. (Defence , 19)65

The heat is familiar, so that England can become capable of New World powers without having to stop being England, can prove alter et idem : tobacco only helps the rheumatic English mind "come to herself."

V

If, as Francis Davison (1602) claims, some critics can insist that poetry too "doth intoxicate the brain, and make men utterly unfit, either for more serious studies, or for any active course of life" (Poetical Rhapsody , 4-5), a commendatory epigram to Sir John Beau-mont's Metamorphosis of Tabacco (1602) can defend Beaumont by comparing his poetry to tobacco's self-consuming influence:

TO THE WHITE READER

Take up these lines Tobacco-like unto thy brain,

And that divinely toucht, puff out the smoke again.

( Poems , 272)

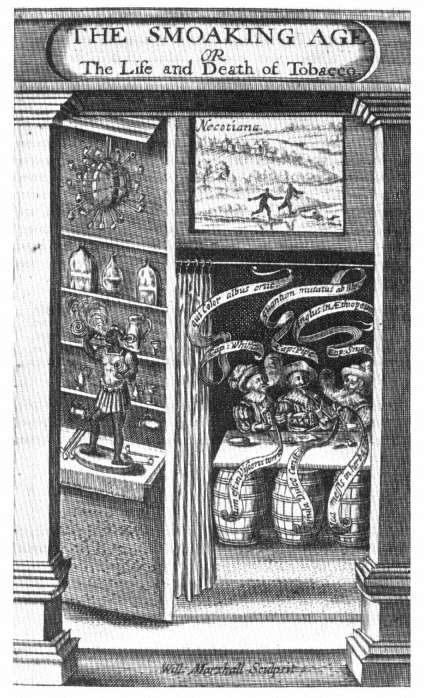

Figure 6.

Frontispiece to The Smoaking Age , by Richard Brathwait, London, 1617. The

upper scrolls read "Qui Color albus erat. / quantum mutatus ab illo. / Anglus in

Æthiopium " (whose color was white. / how much changed from that. / an Englishman

into an Ethiopian). (By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.)

Beaumont himself quickly implies that the primary metamorphosis of his title is tobacco's transformation into his poetry, a transformation unabashedly evoking the savage practice Monardes describes and Philaretes abhors:

But thou great god of Indian melody

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

By whom the Indian priests inspired be,

When they presage in barbarous poetry:

Infume my brain, make my soul's powers subtle,

Give nimble cadence to my harsher style;

Inspire me with thy flame, which doth excel

The purest streams of the Castalian well.

(276-77)

Where Marbecke tries to reconcile savage to Christian value, Beaumont characteristically insists on celebrating those features of Indian smoking, the superstition and barbarity, that most stand in the way of such a reconciliation. Beaumont's dedicatory poem to Drayton had warned readers that Beaumont would prove irreverent, since it emphasizes that the dedication is meant to be as much an affront to the powerful as a compliment to a friend: Beaumont claims he "loathes to adorn the triumphs of those men, / Which hold the reins of fortune, and the times." The Latin tag ending the dedication, from Catullus's dedication of his own work, embraces the poet's professed marginality less militantly, joking now about Beaumont's intellectual poverty: to whom better should I dedicate my poem, asks Beaumont, namquam tu solebas / Meas esse aliquid putare nugas , than you who used to think my trifles something. Yet with the rigor of a puritanical antagonist, Beaumont in his invocation completes the traditional assault on fruitless poetry by allying his poem not only with poverty and inanity but with superstition. For Beaumont subscribes to an alternative—in his view Spenserian—system of "estimation," whose genius is "the sweet and sole delight of mortal men, / The cornu-copia of all earthly pleasure" (275).66 If poetry's influential critic Henry Cornelius Agrippa declares that poets super fumo machinari omnia (Eiv), or, in the Elizabethan version, "devise all things upon a matter of nothing [fumo , smoke]" (33), then Beaumont will celebrate the "Castalian well" of fumo —tobacco.

After its invocation, in fact, the poem embarks on two myths of

tobacco's creation that celebrate tobacco's worth as against the religious and temporal orthodoxy separately scorned in dedication and invocation but now combined in the figures of the Olympian gods. In the first myth, Earth and her subjects frustrate their oppressor, Jove, by enlivening Prometheus's subversive creation, man, with the flame of tobacco (Beaumont, Poems , 277-86). In the second, less contentious tale, Jove courts a beautiful but standoffish American nymph who outshines Apollo; Juno angrily transforms her into a plant—tobacco; but Jove retaliates by further metamorphosing his former love into "a micro-cosm of good" (286-304). While both myths associate tobacco's value with the victimized and profane, one last account of tobacco moves closer to conformity, though only in order to attack still another kind of tyranny. This account takes the premise of the second myth further, and decides that the gods must always have been ignorant of tobacco, or else, "had they known this smoke's delicious smack, / The vault of heav'n ere this time had been black" (304). The more the Olympians are imagined as prone to love "the pure distillation of the Earth" (304), the more their powers and authority are blotted out, blackened; for their love of tobacco assimilates them to Harriot's Indian gods, and by implication, the pagan Greeks and Romans to the pagan Indians.67 In other words, Beaumont involves tobacco in a rebellion now against not only religious or temporal authority but also "the purest stream of the Castalian well," the authority of the classics. Even the gods' ignorance of tobacco damns the classical world, by reminding Beaumont's readers of one of the first and most powerful intellectual reactions to America's discovery, the realization that the ancients had, for all their intimidating genius, proven profoundly benighted—"Had but the old heroic spirits known" (305)!68

Yet Beaumont does not want the subversion of one orthodoxy to become a triumph for another: he now explicitly asserts that those "blinder ages" (306) were indeed wrong to worship Ceres, for instance, but only because they ought to have worshipped tobacco instead. Modem times, he claims, have not abandoned superstition but discovered improvements on it:

Blest age, wherein the Indian sun had shin'd,

Whereby all Arts, all tongues have been refin'd:

Learning, long buried in the dark abysm—

Of dunstical and monkish barbarism,

When once the herb by careful pains was found,

Sprung up like Cadmus' followers from the ground,

Which Muses visitation bindeth us

More to great Cortez, and Vespucius,

Than to our witty More's immortal name,

To Valla, or the learned Rott'rodame.

(314-15)

To keep his distance from both orthodoxy and superstition, Beaumont now orthodoxly eschews papist superstition, "dunstical and monkish barbarism," yet in the name neither of humanism nor of the true church but of tobacco.

This last profanity derives a special bite from the fact that, to many of Beaumont's readers, the distinction between Indian and papist paganism would have seemed a nice one indeed. We have already seen how Marlowe conflates the two kinds of "ceremonial reverence" (and apparently some Catholic priests overseas felt the same temptation: in 1588 the Roman College of Cardinals was forced to declare "forbidden under penalty of eternal damnation for priests, about to administer the sacraments, either to take the smoke of sayri , or tobacco, into the mouth, or the powder of tobacco into the nose, even under the guise of medicine, before the service of the Mass"69 ). Chapman's Monsieur D'Olive mocks the similar views of Marlowe's enemies—here, a Puritan weaver reviling tobacco:

Said 'twas a pagan plant, a profane weed,

And a most sinful smoke, that had no warrant

Out of the Word; invented sure by Satan

In these our latter days to cast a mist

Before men's eyes that they might not behold

The grossness of old superstition

Which is, as 'twere, deriv'd into the Church

From the foul sink of Romish popery.

( Monsieur D'Olive 2.2.199-206)

The difference for Beaumont seems to be one of proximity: England has just escaped papistry's "dark abysm," while Indian superstition is at once too distant and too primitive a threat to be

taken seriously. The superior status of a blest age freed from papist barbarism now leads Beaumont to affirm that

Had the Castalian Muses known the place

Which this Ambrosia did with honor grace,

They would have left Parnassus long ago,

And chang'd their Phocis for Wingandekoe.

( Poems , 315)

The wit of the final line depends on perceiving the two place names, one Greek and one Indian, as equally outlandish and barbaric—on the suggestion, again, that the ancients were no better than the Indians, or still more wishfully, that the authority of the classics, as of the Indian "people void of sense" (315), depends on the playful attribution of that authority by the enlightened English reader.

One might say that the comical mixture of classical with Indian subject matter focuses power on England as the excluded middle,70 whose perfect representative would now seem to be "our more glorious Nymph" (315), the virgin more successful than tobacco in withstanding the encroachments of the powers that be, of superstition East and West—that "heretical" authority, Elizabeth. Earlier in the poem Elizabeth had already enabled Beaumont to make a provisional act of obeisance to the status quo: he had claimed that, just as tobacco has replaced Ceres in the heaven of the superstitious, so Elizabeth has replaced tobacco. Wingandekoe, the American home of the tobaccoan nymph, "now a far more glorious name doth bear / Since a more beauteous nymph was worshipt there": as Beaumont's note explains, "Wingandekoe is a country in the North part of America, called by the Queen, Virginia" (286-87). The moral would seem to be that Elizabeth outshines the dreams of the superstitious pagan; modem historians of Elizabeth's cult would conclude that Beaumont wants to substitute worship of the queen for the cast-off "superstitions" not just of paganism but of papistry, so that Elizabeth can absorb Catholicism's displaced authority.71 Yet here Elizabeth does not stand apart, virginal, from the superstition whose authority she absorbs. The terms of praise for Elizabeth that follow—the queen is, for example, "our modem Muse, / Which light and life doth to the North infuse," "In whose respect the Muses barb'rous are, / The