Submarine Canyons off La Jolla

The La Jolla coast is somewhat unique in having two submarine canyons that extend virtually in to the beach (fig. 78). One of these canyons is located off the cliffs north of Scripps Institution, and the other is off the south end of the long beach at La Jolla Shores. Both canyons are rather clearly related to the land valleys at their heads. The northern one, Scripps Canyon, extends southward in an almost straight line and has vertical, and even overhanging, walls all along its length for about a mile out, where it joins the less precipitous La Jolla Canyon. One unique feature of Scripps Canyon is its constantly changing depths. It fills gradually for a number of feet, and then a slide, sometimes combined with a turbidity current, carries the sediment seaward, often with enough force to remove large boulders along its course. It has several side canyons at its head and, from time to time, new or old buried tributaries are apparently uncovered, which may subsequently be refilled.

La Jolla Canyon has steep sides and a vertical headwall but is generally less precipitous than Scripps Canyon. It extends for thirty-three miles seaward in a general southwest direction and enters San Diego Trough twenty-seven miles off the coast at a depth of 3,600 feet. Dives into the head of the canyon show it to be unstable, and the character of the bottom changes at frequent intervals of time. The surrounding terrace has yielded many artifacts, some dated at approximately 4,200 years old. There is substantial evidence that the head has been retreating shoreward at an average rate of about one inch per year for the past few thousand years (Shepard and Dill 1966:57–58). Shepard and Dill (1966) also showed that the retreat from 1950 to 1964 was over two feet

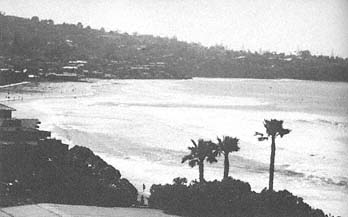

Figure 79

View looking south toward La Jolla Shores, 1978. Note that the

rip currents can be seen in the center of the photo. They form

between the lowest and the highest waves near the La Jolla

Submarine Canyon.

Photo : G. Kuhn.

Figure 80

Sea cliff retreat by removal of the joint blocks of the sandstone bed in the lower-middle Eocene Ardath

shale that caps a bench projecting from the sea cliff 300 feet north of SIO pier; the top is about seven feet

above high-tide level. The sequence of retreat at the edge of the sandstone capped bench: July 1940, May

1944, June 1953, and July 1979. Maximum retreat was twenty-three feet in forty years, but none of the

blocks remain at the foot of the bench front. From Emery and Kuhn 1980.

per year. An interesting feature of La Jolla Canyon is the effect it has on the waves on the long beach at La Jolla Shores. The waves are almost always much smaller at the head of the canyon, owing to wave divergence as the crests move shoreward up the canyon. Conversely, they are much larger at the north end of the beach where the waves converge, so there may be two-foot breakers at the canyon head and ten-foot breakers in the northern convergence, half a mile up the beach. Thus, swimming is easier at the canyon head, and huge numbers of bathers swim there every day in the summer, whereas surfers are relegated to the northern convergence, where they abound. The effects also relate to the rip currents which are an ever-present danger. These rips are in the area between the lowest and highest waves, and the lifeguards are on constant alert for unwary bathers in this zone (fig. 79).