Walter Bernstein: A Moral Center

Interview by Pat McGilligan

The first time I met Walter Bernstein was at a socialist film festival in Burlington, Vermont. On the schedule was a revival showing of The Front, the 1976 standout comedy with a message—written by Bernstein, directed by his longtime friend and associate Martin Ritt—about the blacklist period in show business, with Woody Allen as the schlemiel who doesn't back down when bullied by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). After this and other programs about the blacklist, a panel of former blacklistees convened, which included the animator Faith Hubley, the documentary filmmaker Leo Hurwitz, and the screenwriters Maurice Rapf and Walter Bernstein.

Afterward, Faith Hubley introduced me to Bernstein. Faith knew Walter from days of youth, and from her and other people, I already knew that he was a person of enormous warmth and likability, as well as an iconoclastic firebrand with a slashing comic sensibility. One of the reasons for his long, continuing career and his early breakout from the blacklist may be his likability. More than most screenwriters, Bernstein has persistently managed to get away with social statements in his produced scripts. His candor, sense of humor, and easy rapport with directors and producers has worked to his advantage.

One of the last of the blacklist era who is still active writing scripts, Bernstein began his career in the late 1940s with a Hollywood stint, which was interrupted by the blacklist (though he kept more than busy in television and with "fronts"), and his career reached a zenith in the 1960s and 1970s, with films such as Fail-Safe, The Molly Maguires, The Front, Semi-Tough, and Yanks. These are his best and most personal credits and, not coincidentally, are the ones most faithful to his scripts. In 1980, Bernstein took a detour into directing the remake of Little Miss Marker. Although the work officially slowed down, he did a lot of script doctoring in the 1980s and, between Holly-

wood credits, kept up a strategic presence (like many another refugee from the Golden Age) in the relatively open-minded field of cable television, where he found a temporary haven for his kind of film—stories with stance, troubling themes, and a moral center.

"Return to Kansas City" (1992), one-third of the Women and Men 2 series, gave Bernstein an opportunity to adapt and direct a short story written by an old friend, Irwin Shaw. Doomsday Gun (1994), a true-life tale about a Reagan era arms merchant gone amok, was a compelling extension of topical ideas first explored in Bernstein's adaptation of Fail-Safe.

Throughout his career, Bernstein has written short stories and reportage (including a book of his columns from the New Yorker during World War II called Keep Your Head own! ). His "Marilyn Monroe's Last Picture Show," published in the July 1983 Esquire —Bernstein was the finishing writer on her last and unfinished film Something's Got to Give —is definitive journalism on Monroe. His critique of Elia Kazan's memoir, A Life ("Elia Kazan: A Stool Pigeon Named Desire," In These Times, July 6–19, 1988), is an equally conclusive character study of opportunism and deviousness. "He is not dirt," Bernstein wrote of Kazan. "No one is. But he soiled himself, and the stain remains."

The blacklist remains a live grenade for Bernstein. At the Barcelona Film Festival in 1988, he found himself involved in a panel discussion on the McCarthy era witchhunt with the director Edward Dmytryk and his wife among those, quite unexpectedly, in attendance. Dmytryk, who cooperated with the HUAC inquisitors after an initial term in jail as one of the Hollywood Ten, told the audience, "I never regretted anything I did. I feel myself a free man. McCarthy had nothing to do with it." Jules Dassin was one of the panel members who took the occasion to vehemently attack Dmytryk. Bernstein was another. "Mr. Dmytryk is scum," Bernstein told the audience. "It's not a debatable subject. I'm not interested if he's free or not." By the end of the nearly two-hour session, Variety reported, "Dmytryk's wife was in tears."[*]

Not only did Bernstein write The Front and The House on Carroll Street (1988)—a less successful but still rewarding Hitchcock-style mystery-drama, set in the McCarthy era, peppered with Nazis and spies and anti-Commie fanatics—but there is also his other blacklist script. This serious comedy is based on an unproduced play of Woody Allen's, and was originally intended to star Martin Ritt as a vulgar TV producer. After Ritt died, the film project was temporarily set aside, but now and then, Woody Allen talks of reviving it.

After I met and got to know Bernstein, I also met and got to know his wife, Gloria Loomis, who is now my agent. People who would like to know more,

* Peter Besas, "Old Wounds Reopened during Symposium on McCarthy Era," Variety (July 6, 1988).

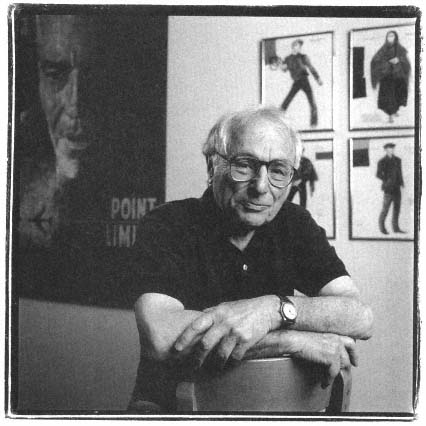

Walter Bernstein in New York City, 1994. (Photo by William B. Winburn.)

after reading this interview, about Walter Bernstein's richly eventful life and career, will be happy to learn that he recently completed Inside Out: A Memoir of the Blacklist, which was published in late 1996 by Alfred A. Knopf.

| ||||||||

|

Television credits include numerous script contributions to episodic television including The Somerset Maugham Theatre; Danger; Charlie Wild, Private Eye; Colonel March of Scotland Yard; You Are There; Studio One; Westinghouse Playhouse; and Philco Playhouse; and "Return to Kansas City," Women and Men 2 (1992, adaptation and direction); Doomsday Gun (1994, telefilm, co-script); and Miss Evers' Boys (1997, telefilm, script).

Nonfiction books include Keep Your Head Down!

Academy Award honors include an Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay for The Front.

Writers Guild honors include nominations for Best Script for The Front and Semi-Tough. He also received the Ian McLellan Hunter Memorial Award for Lifetime Achievement presented by the Writers Guild-East in 1994.

Am I right? Did you start out as a newspaperman?

I started out as a fiction writer. I sold a story to the New Yorker when I was in Dartmouth. They published another story of mine, and then the war came along. I went into the army and started writing nonfiction: "Reporters-at-Large" for the New Yorker. Also I was on the army magazine called Yank.

After the war, the New Yorker pieces were published in a book that Viking put out called Keep Your Head Down! [New York: 1945]. It's a collection of all

the "Reporters-at-Large" I wrote over the four years I was in the army. It's a book about me, really.

Oh, is it a good book?

I think two or three of the pieces would stand up—the combat pieces would stand up. There's a long, three-parter at the end of the book about my getting into Yugoslavia . . .a kind of very gung-ho, lefty piece . . .that I don't know about. The rest I think would be very dated.

Was it hard for you to switch to nonfiction?

No, I liked doing it right away. After I got out of the army, I went to work for the New Yorker for about a year, writing other "Reporters-at-Large" and that kind of thing. I tried to write fiction again. I wrote a couple of stories which the New Yorker published during that time.

I didn't quite know what I was going to do after the war, actually. When I came back from overseas, I found myself a father with a year-old daughter. It was tough to get adjusted. But what I really wanted to do was to go to Hollywood. Movies had always been very important to me.

Why?

That's where I lived my real life. My fantasy life was at home. Starting Friday evening, after school and going through till Sunday afternoon, I lived in the movies. There was always this sense of weight dropping off me when they took the ticket and I walked into a moviehouse. It was very palpable, very important. I loved the movies.

Was that because your home life was so unhappy?

It wasn't happy. It wasn't unhappy. My father was a schoolteacher. We weren't affected by the Depression. The Depression was happening all around us, but we weren't affected.

You had to be solidly middle class to end up going to Dartmouth.

It was my father's dream that I go to Dartmouth. All I cared about was getting out of town. He knew somebody who was a prominent alumnus [of Dartmouth], and that's how I got in. My marks weren't particularly good. But Dartmouth was an experience. Going up to New Hampshire and New England was wonderful. I loved it.

Could you keep up with movies at Dartmouth?

There was a student there named Lester Koenig, a senior, who later became an associate producer for Willy Wyler.[*] He was [eventually] blacklisted also. When he was blacklisted, Lester went into the record business—jazz

* Lester Koenig met the director William Wyler while producing training films during World War II, and later served as his associate on films including The Best Years of Our Lives and Roman Holiday. Later, he formed the Good Time Jazz and Contemporary labels, recording top jazz artists such as Art Pepper, Ornette Coleman, and Benny Carter.

records—where he was quite successful until he had a heart attack and died. At that time, Lester was the movie critic for the Dartmouth. When Lester left, he bequeathed the job of movie reviewer to me, so I would see the movies that came up, a few times a week.

I got into trouble for panning Lost Horizon [1937]. I wrote a scathing review of it. For some reason, that caused a big commotion on campus. The man who defended me was a very interesting man named William Remington, who later, in the early fifties, lost his government job in a big Red purge and was sent to jail. He was killed in jail, bludgeoned to death.

Anyway, I was kicked off the newspaper. The only other movie experience I had at Dartmouth was when director Leo Hurwitz and [the photographer] Paul Strand came up to photograph Native Land [1942], and I drove them around while they were shooting.

Hollywood sent a number of their people to Dartmouth for some reason. Budd Schulberg, Maurice Rapf, Peter Viertel . . .Walter Wanger, who had been an alumnus, was very active in trying to set up a film department at Dartmouth.

It was this isolated, Republican, very reactionary, and very beautiful school. I liked it there. Of course, I knew, being a poor student and coming from Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn, with five thousand battling students, that I wouldn't have to work hard. I would get through okay.

All these kids from prep schools! I was very awed socially because I had never seen people wearing jackets that didn't match their pants. Where I came from, you wore a sweater, or you wore a suit. There was no such thing as sport jackets or odd pants.

Did you arrive at Dartmouth with a social conscience?

I had graduated from high school in the middle of the year—in January-February of '36; in those days, they had so many kids that they graduated them twice a year. My father had some idea of me that I was trying to fulfill, so he sent me to France with my high school French. I was terrified.

It was very exciting to be in France at the time. This was during the period of the sitdown strikes and the Popular Front. I fell in with a group of English kids who were also studying there, some older than I. They were very left wing. One of them was a big, hot Communist youth named Robert Conquest, who later became an avid right-wing anti-Communist and expert on the Gulag. Then the Spanish Civil War broke out. Conquest went down to Spain and wanted me to come with him—they were having an alternative workers' Olympics in Barcelona. I didn't have enough money and had to go home. But that started my political consciousness, the Spanish Civil War and antifascism . . .

Your politics didn't come out of your home situation?

No. I had a Communist aunt, a charter member of the Communist Party. But she was the black sheep of the family, and I didn't hardly talk to her until I was sixteen.

So, you 're not a Red-diaper baby?

Not at all. Then, when I was at Dartmouth, from '36 to '40, it was a very active time politically, because of the Spanish Civil War. Budd Schulberg had just left campus, and he had been a big left-wing editor of the daily paper. There was a lot of activity going on amongst a small group of us.

Beyond that, the war really formed me. I Was lucky in that I went overseas for Yank, was able to move around; I got into Yugoslavia surreptitiously, interviewed Tito, and spent some time with the partisans in Italy. That really made me what I am, essentially, still.

Anyway, after I got out of the army, I had my book published. I met an agent through a friend by the name of Jerome Chodorov, the writer. Jerry's agent was Harold Hecht. Hecht got me a job working for Bob Rossen, who had the idea of making a movie out of a Chekhov story called "Grasshopper," about this flighty woman.[*] Rossen had a deal with Columbia, then. He had just finished directing Body and Soul [1947], and was hot.

Had you known Rossen previously?

No. I didn't know anybody at all in Hollywood.

Except through Dartmouth connections . . .

Well, Schulberg is the only one I really knew—only from visiting. He had come back my freshman year to work on [the novel] What Makes Sammy Run? He was very nice to me, by the way.

Anyway, I went out to Hollywood in July or August of '47 with this tenweek deal at Columbia, and I stayed for six months. Rossen and I talked and quickly discarded "Grasshopper." He was working on All the King's Men [1949], so I worked on that with him But I didn't really work. I really sat and listened to him. He would use me as a kind of political barometer.

Why? He thought you had correct politics?

Yeah. It was a very funny time. One day he wanted to move the desk in his office from one place to another. He look one end and I took the other. All of a sudden, this man appeared in the doorway—tough-looking, bald-headed man. "What are you doing?" "Moving the desk." "It shouldn't go there, it should go here. C'mere." He took the other end of the desk. He looked at me and said to Rossen, "Who's that? One of your Commie writers from New York?" Rossen laughed and said, "Yeah." It was Harry Cohn.

* Robert Rossen was a veteran Warner Brothers screenwriter (Marked Woman, The Sea Wolf, The Roaring Twenties, etc.) who graduated to directing in the late 1940s with hard-hitting films, which he sometimes scripted, including Johnny O'clock. Body and Soul, All the King's Men (which won the Oscar for Best Picture in 1949), and The Hustler (which won the Oscar for Best Picture in 1961).

Rossen knew my politics, and I knew his. He'd go down for meetings with Cohn and come back after having sold out some important political point, and we'd talk. (Laughs. ) He was doing a juggling act, trying to make things work. But I learned a lot from him, just sitting and listening to him. He was very much a Warners product, that 1930s ethic. He was very ambitious, feisty. I rather liked him. And I got him to tell me stories about the Warner Brothers days . . .

Can you characterize what you learned from him in terms of script?

I learned about moving a story in terms of action—a kind of movie storytelling. At one particular point [in the script of All the King's Men ]—it sticks in my mind—Rossen was trying to figure out how to tell the audience that the Huey Long character was not just a marvelous idealist. He wrote a scene—he didn't like it; it was too wordy. Then he came up with some idea of a scene with no dialogue, where Broderick Crawford is eating a piece of chicken as people are extolling him—cutting to him and his indifferent reaction—so that we know that he's not buying any of it. Things like that—visual detail, not dialogue—I learned that from Rossen.

Why did Rossen need you at that stage of his career?

He didn't need me. I think he liked me, and he liked having me around. I served as a sounding board for him, not just politically but in other ways.

He ended up writing that script himself, right?

Actually, the one who did a great deal of work and wrote a complete script, whom I always think got screwed on the credit, was Norman Corwin.

He did? He isn't credited on the screen.

Somehow Norman got screwed, because the script I read—afterwards, with his name on it—was not that far off from the script that was shot.

Anyway, the ten weeks were going to be up, and Rossen asked if I would stay on. But Hecht had just formed his company with [Burt] Lancaster at Universal, and their first film was going to be a thing called Kiss the Blood off My Hands.

I was getting $250 a week from Columbia, and Harold said he could get me $500. Besides being the producer, he was also my agent; so he took his percentage. I went to Rossen and told him they were doubling my salary at Universal. He said good-bye and good luck. I went over there, and they put me together with Ben Maddow, who had no experience.[*] I spent another four to five months, very happy months, working with Ben on that script.

Again, I learned a lot. Ben was the best pure screenwriter that I've ever met—really—in the sense of knowing that medium, understanding it, and working in it.

* Ben Maddow's long, fascinating career as a poet, documentarist, photography criticessayist, and screenwriter is treated in Backstory 2.

We wrote what I always thought was a very interesting, odd, Hitchcockian kind of script, that I liked. Our script was never filmed. On the basis of our script, they got the director [Norman Foster], [the cinematographer] Gregg Toland, and Joan Fontaine to play opposite Lancaster. Then they did what they usually do. They hired another writer [Leonardo Bercovicci] who, I felt, made it much more ordinary than it was. I think the structure is still ours but very little else.

It's true ours was a kind of strange script, but I liked working on it with Ben, and I got to know Lancaster, because I didn't have a car and lived in Beverly Hills. He was shooting All My Sons [1948] at Universal at the time, so he would pick me up in the morning and drive me to the studio and talk.

Did Lancaster have any political convictions or affiliations?

I don't think so. He was very unformed still. He would ask me questions about what books to read or what music to listen to. He wanted to take acting lessons to be a better actor, but Harold wouldn't let him. In the story conferences, I always had learned to listen to what Lancaster had to say, even when I didn't agree with him, because his concerns always came out of something real. They came out of intelligence and looking for something. I liked him, though he was a strange man in many ways.

I finished that picture, and I had to make a decision whether to stay in California. I had two kids by then, but my marriage was foundering. So I went back to New York, at Christmas of '47, for domestic reasons, essentially. I had had a very good time in California, the kind of good time I would have later on in Los Angeles. But I was unsure where I wanted to live.

After I went back, the marriage broke up. The divorce was a difficult, messy one. I had intentions of continuing to work in movies. But I felt I had to stay in New York. I was just beginning to work in live television when I got blacklisted, and that put a stop to movies.

Tell me how you first met Afarty Ritt and Sidney Lumet, how far back you go with them, and why you proved so compatible with them as friends and collaborators.

Marty and I met first. Marty I met shortly after the war—'45 or '46. I'm vague about how we met or through whom, but we became friends. We used to play ball together in the park on Sundays, softball in the spring and summer, then touch football in the fall. My happiest memory of those days—which doesn't involve Marty, although he was in the game—is blocking out Irwin Shaw, who weighed about one hundred pounds more than I did, so that John Cheever could run for a touchdown. trwin was astonished, and I was pleased.

Then, in the late forties, Marty and his wife practically supported me. I lived with them after my marriage had broken up. I lived on then" couch. They had a little one-bedroom apartment on West Twenty-second Street. His wife was working for the Yellow Pages, selling space, making very little money, so Marty supported us by gambling.

We fast started working together in television. Marty got a job directing something called The Somerset Maugham Theatre, a half-hour dramatic show based on Maugham's stories. I wrote some of those for him. And Sidney and I fast met on a half-hour show at CBS called Danger. Marty had been the producer and Yul Brynner was the director and Sidney was Yul's assistant. When Marty and Yul left the show, Sidney became the director, and that's when our friendship started.

Marty and Sidney and I all came from the same kind of background—New York, Jewish. Sidney and Marty had both acted in the Group Theatre. Sidney had been a child actor; his father had been an actor in the Yiddish stage. So we all came out of a certain, naturalist thirties tradition—Clifford Odets and those kinds of plays. We tended to relate to the same kind of material, apart from whatever our personal feelings were about each other.

What was your attitude toward television?

Television was just starting. Live television was very attractive because it was dramatic writing. It wasn't really movies, more like the stage. You were making it up as you went along. Nobody knew what it was supposed to be. And a lot of very talented people were involved in it—like Marty and Sidney.

Those Danger shows were actually quite good, as I remember them, although they were done quickly. One of the early Danger shows I wrote, which was called 'The Paper Box Kid" and based on a Mark Hellinger story, starred Marty as an actor. It was a half-hour show in which Marty played a hoodlum who goes to the electric chair. Marty hadn't acted for eight years or something like that, and he just exploded. He was wonderful, just wonderful—the show was an incredible success. People would stop us in the street or at the racetrack for weeks afterwards and talk about it.

There was also a show for Herb Brodkin called Charlie Wild, Private Eye, a half-hour show. I forget what we got for a script in those days—$200, maybe. That whole show was done for $5,000, in which the packager took $1,500,1 remember. But the show was kind of fun.

I gather this was just on the cusp of the blacklist. How did you find out that you were going to be blacklisted?

Well, the producer of Danger was a man named Charles Russell, who had been an actor under contract to Sam Spiegel at a time when he was "S. P. Eagle." Charlie had given acting up and become a producer—he was a very nice, totally apolitical guy. Anyway, Charlie came in one day and said, "I can't use you." I said, "Why not?" He said, "They just told me you're on some sort of list. I'm supposed to tell you we're using different writers . . .or we're changing the style of the show . . .or something like that." I said, "Oh." He said, "Just put another name on the script." He was really sticking his neck out, because if they found out about him, he would have gotten in trouble.

So I did that. I wrote a few shows under a pseudonym. Then they were kind of getting wise and began demanding real people, fronts, so I had to get fronts.

Did you have any alternatives besides writing/or television?

I did a few magazine pieces under my own name before the television thing got started—that was still a little area that I could work in. I wrote a piece for Argosy, for example, on the life of a jockey. But I couldn't make a living.

Why were you blacklisted, how were you named, in the first place?

I was blacklisted because my name was in Red Channels. That's the only thing. I was never named, at least publicly. I was subpoenaed later on, but I never appeared.

Why were you in Red Channels?[*]

Six or eight listings—Russian war relief, anti-fascist appeal, Spanish refugees, an article for the New Masses, something for a black veterans' organization . . .oh, they were all true.

Could you go and confront anyone in television about it?

Nah. Because they would always deny it—either deny it, or the networks had someone then—some vice president of affairs—who dealt with that sort of thing, and who would ask you for a statement to clear yourself. Or you could go to George Sokolsky or Frederic Woltman in the World-Telegram . . . one of those things. Since I wasn't about to do that, it was academic.

For the next eight years, it was a question of getting different fronts and working that way. Around that time, Abe Polonsky came east, and along with another man I had become friends with, named Arnold Manoff, we formed a kind of group, the three of us, trying to get fronts and helping each other get work.[**] We wrote many of the subsequent Danger shows. Then they started a show called You Are There, and we wrote almost all of those under various names.

* According to Larry Ceplair and Steven England's authoritative The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community. 1930–1960 (Garden City, N.Y: Anchor Press, 1980), "Taking up where HUAC left off, the American Legion and a private firm called American Business Consultants culled HUAC and Tenney Committee reports, appendices, and hearing transcripts, back issues of the Daily Worker, letterheads of defunct Popular Front organizations, etc., to compile a list of people who could not be accused of 'Communism' but who had, at one time or another, dallied with liberal politics or causes. The Legion published two magazines. Firing Line and American Legion Magazine, and ABC put out a periodical entitled Counterattack and an index called Red Channels; all these publications carried attacks on individuals, organizations, and industries, as well as long lists of names of 'Subversives.'"

** Abraham Polonsky is best known for his Academy Award—nominated script for Body and Soul, and for writing and directing Force of Evil in 1948; then, over twenty years later, after the interlude of the blacklist, for the writing and direction of Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here in 1970. The screenwriter, playwright, and novelist Arnold Manoff, whose career was abbreviated by the blacklist, had several 1940s screen credits, including Man from Frisco, Casbah, and No Minor Vices, for which he received a Writers Guild Award nomination. He worked for television and films under several noms de plume in the 1950s. His wife was the actress Lee Grant.

I also worked on Studio One, Westinghouse, Phiico Playhouse —mostly the one-hour dramatic shows. I did everything from Thomton Wilder's The Bridge of San Luis Rey to, I remember, an adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald's short story "Rich Boy," which starred Grace Kelly and was a very successful show.

Did the three of you have anything to do with the Robin Hood series?

Ring [Lardner Jr.] and lan Hunter did most of those. Abe and I did a show for that same woman, [the producer] Hannah Weinstein—Colonel March of Scotland Yard, with Boris Karloff. We wrote a bunch of those together.

Did the three of you actually pool your money?

No. The group had very strict rules. Whoever found a job, that was his job, and it was up to him if he wanted to share it. If I was working on something and heard about something else, I could then bring it into the group, and we might decide among us who needed to do it. But whoever did the work, that was their money. The money was never shared. What the group had was an obligation to help anybody on a script. If I was having problems on a script—on You Are There particularly, we were always trying to figure them out—we'd do them together.

The thing that made it work is we were all on the same level of competence. Since producers never knew what style was—one person's style—we could get away with it. For example, on the You Are Theres, I did all the Civil War stuff; Abe took the weighty subjects, like Savonarola and Galileo and Beethoven; Amie did the philosophical stuff like the death of Socrates. We did what interested us, and it was a very happy arrangement.

Did you talk about the ideas you were putting into the work, consciously? Did the three of you get in a room and chortle over some political parable you were writing?

No. Never. The only thing we chortled over—and chortle is really not the word—is the You Are There shows. At that particular time, it was right in the middle of the McCarthy era, and a lot of the shows were very strong civil liberties shows, about Galileo or Milton. Some were quite tough and very good. They were a strange combination of camp and closely reasoned, dramatic stuff that we felt very good about and were conscious of doing. The other stuff, no.

On the other hand, I was talking to Sidney Lumet once about the Danger shows we did in the 1950s—those half-hour melodramas—and we realized, talking about them, that they were all about betrayal, all quite grim. I suppose that's the way I felt at that time . . .and it's true that sometimes the things I felt closest to were the stories about people doing rotten things to each other.

Where would you get your fronts?

They came from all kinds of places—from people who wanted the credit because they were trying to get ahead; from people who wanted the money. Some people did it out of friendship—those were the ones who lasted. The

ones that did it for the other reasons never really lasted. They'd get worried. Ego would interfere in some way.

I remember there was a very nice man, a good writer, who let me use his name for a couple of shows. It was a bad time of my life. They were comedy shows and not very good. He got very upset I was letting him down with his name on them. In a very nice way, he detached himself from it. I couldn't blame him.

The front that worked the best for me was an old friend of my brother's, someone I had known since I was ten years old, who had a job on a trade paper, didn't want to take any money for being a front, and kind of liked the whole idea of going up to story conferences—the playacting part of it. He was the one I used mostly. He was very helpful.

You think of that period as being such an awful period, and it was. But within that, that sense of friendship and helping each other—which we all did, not just the three of us—was very real.

One of the things that was sad after the blacklist was that everybody went back to the same, old, dog-eat-dog kind of thing. People remained friends, but the whole camaraderie, that whole sense of helping each other, as part of your existence, disappeared. I missed that.

Your partnership withAbe andAmie was happily sustained/or eight years?

Yes. It was very important. Of course, we all did things outside the partnership. Abe went and did a movie in Canada, Oedipus Rex [1957], with Tyrone Guthrie, I think. Abe also wrote a movie for Harry Belafonte and Bob Ryan, a grim melodrama called Odds against Tomorrow [1959] . . .

But you yourself didn't do anything in motion pictures for eight years, from '50 to '58.

No. Only television. My contacts in movies were very limited. Until, in '58, Sidney Lumet got a movie to direct [That Kind of Woman ]. The producer was Carlo Ponti. They needed the script rewritten, and Sidney called me. Ponti didn't know from American politics, and he hired me with, I assume. Paramount paying my salary. Since I wasn't known out in Hollywood at all, since I hadn't been active at all politically out there, I was able to work. I did the script and in fact went out to Hollywood to finish it up.

My agent, Irving Lazar—he was introduced to me by Irwin Shaw, and became my agent on this movie—got me a lot of money. Lazar told me he could always get more money for someone who was new than for someone who had been around a long time. Funny, I went to Europe later on to do films for George Cukor and other people, and when I came back—it was less than a year later—I found I couldn't get a job. I called Lazar and asked what was happening. He said, "Look, someone like you makes a lot of money, so it's hard for me to get you a job . . . " This was less than a year later! I guess I had stopped being new.

Anyway, Paramount liked what I was doing, and they were talking about me working for Ponti again. As I was finishing the script, Lazar called me and said Paramount had decided not to make a new deal, because there was a subpoena out for me. The House Un-American Committee was having what turned out to be their last hearings—this was in '58, I guess. I said, "Thank you very much," packed my bags, left, and flew back home.

I went to stay with a marvelous pair of people named Harvey and Jesse O'Connor, an old radical journalist and his wife. They had a great house in Rhode Island. I hid out there and finished That Kind of Woman. Leonard Boudin was my lawyer. He got in touch with the committee, who confirmed there was a subpoena out for me. The hearings were held in New York, and I wasn't served. That was the end of it.

It was very funny, because around that time I had a meeting with Ponti—Ponti, an interpreter, Boudin, and me. Leonard explained what had happened, what my position would be, that I was not going to be a cooperative witness. The interpreter translated everything. Ponti said something to the interpreter in Italian. The interpreter turned to us and said, "Mr. Ponti would like to know who has to be fixed and for how much . . . " It was all politics, bullshit, to him. Making a movie—now, that was serious. His attitude was, let's just pay somebody off and get to work.

Was there ever any question that you might not get your screen credit on That Kind of Woman?

No. That issue never came up.

Wasn't that sort of unreal at the time?

I didn't know. Everything was going so fast then.

When Sidney first talked to you about That Kind of Woman, he had a political background, he must have been aware that he was heading into unknown territory by employing you?

Oh, sure. He had known about me working all those years with a front. It was no secret. He was complicitous in that.

Most sources say Dalton Trumbo broke the blacklist with Exodus in 1960. That means you came up with a screen credit almost two years before. That puts you at least two years in the vanguard. At the time, you were not particularly aware of it?

No, Marty Ritt had gone out to Hollywood, and the impression he had was that the blacklist wasn't as firm as before . . .

Was there a sense of there being more loopholes on the East Coast?

No. But by '58, there were cracks in the blacklist. Although, at that last hearing, Lee Grant, who was married to Armie Manoff, was called to testify, and several other people too . . .

Your relative anonymity in Hollywood served you well at this juncture.

I think so. Otherwise, I wouldn't have been hired. But after I finished the first script, I couldn't get another job. Paramount was still insisting I testify.

There was this writer, Robert Alan Aurthur, who had helped Marty get his first directing job.[*] Now, Aurthur was going to write The Magnificent Seven [1960] for United Artists. Marty [Ritt] was involved in some fashion. They were also involved together in planning the movie about Spartacus.

Originally, they had asked me to write The Magnificent Seven script, but I had chosen the Ponti deal instead. When the second Ponti script fell through, Robert Alan Aurthur went to Marty and said, "I'm not blacklisted. I can work anywhere. I know you offered this to Walter before. So I'll back out. Give it to him now." Marty and Yul [Brynner, one of the stars of The Magnificent Seven ] went to United Artists and took the position with [the executives Arthur B.] Krim and [Robert S.] Benjamin and the others that they didn't know anything about any subpoena; all they knew was that I had just finished a script with Paramount, so therefore I was employable. I was hired and did a draft of The Magnificent Seven.

Yul was supposed to direct it, but then Tyrone Power died, and they asked Yul to replace him in whatever movie he was doing in Spain [Solomon and Sheba, 1959], offering him a lot of money. Yul chickened out of directing, I think. He would have been an interesting director.

After that I went to Lazar and said, "Look, I can work. I've just done this and the other thing . . . " Lazar called Paramount, and they said, "Nope, he's got to go testify . . . "

Then I got a call from one of the executives at Paramount, asking if I would come in and meet with the head of Paramount—a man named Y. Frank Freeman. Very, very reactionary southern gentleman. I said, "Sure"; I went in. He was a very courtly combination of shrewdness and idiocy. He started off telling me a long story about a technician's strike in Hollywood with all of "his boys" out on the picket line. He said he could have settled the strike by going out and talking to them, but "Russian-looking" men kept interfering. (Laughs.)

He had my whole dossier on his desk, going back to college. He said, "Would you mind if I asked you some questions?" He went down the complete list of everything I had ever done. I answered honestly. By that time, I knew I wasn't going to be destroyed—I'd been through the blacklist—and I wanted to work. I said, "Yeah, I still believe in this . . . I'd still do this . . . maybe I wouldn't do this anymore . . . but it's all true." He liked me. He said, "I've helped people like you in your situation," and he proceeded to name a

* The writer-producer Robert Alan Aurthur was a prolific writer of articles, short stories, books, plays, teleplays, and motion picture scripts. His adaptation of Arthur Koestler's Darkness at Noon won an Emmy. His story "A Man Is Ten Feet Tall" was adapted by him for the director Martin Ritt's feature film debut, Edge of the City. Aurthur's other screen credits, alone or in collaboration, include Warlock, Grand Prix, For the Love of Ivy, The Lost Man (in which Aurthur doubled as director), and All That Jazz.

couple of the stool pigeons—Sterling Hayden, I forget who else. He said, "I want to help you. Be honest with me. If you get subpoenaed, what are you going to do?" I told him what I was going to do—be an unfriendly witness who wouldn't name names. He said, "Well, don't go then. There's no point in going if that's what you're going to do." He said, "Let me think about this. Let me consult with my good friend Jim O'Neill, who is head of the American Legion, who I talk to about things like this, and I'll get back to you." I said, "Fine." Two weeks later, they called me and said, "You can work." That's how I got cleared. Because Y. Frank Freeman liked me, and also because I had a kind of-don't-give-a-shit attitude. I wasn't interested in arguing.

By that time, I think, the end was beginning, although I still could not work in television for two or three years afterward. The irony of it is, the next television I did was much later on when they tried to revive You Are There as a Saturday afternoon children's show. The producer called me and asked me to do a couple. I said, "Sure," as long as I could put my own name on it this time.

The second script that Ponti wanted you to do was Heller in Pink Tights, for director George Cukor, right?

Right. Dudley Nichols had written a script or a treatment, but he was very sick and couldn't go on with it. I was introduced to Nichols once, I think, when I first came to work on the script, but I never saw him again. I knew who he was, of course. I was very impressed by him.

They had a start date, and they had Tony Quinn. Since I was under contract to Paramount, they put me on the script, and I wrote that picture about a week ahead of shooting . . . sometimes they would catch up to me, so that I'd be bringing in the pages in the mornings they were supposed to shoot that very day. It was both a good and a terrible position to be in—if you could bring them something they could shoot, you were a hero.

Was director George Cukor involved at all in the scriptwriting process?

Yes, but everything was so hectic. George was much more involved with [the art directors George] Hoyningen-Huene and Gene Allen, and the style of the picture, really. It was not his kind of movie really, a western. What interested him was the idea of this theatrical troupe in the West—this kind of picaresque, crazy bunch of people.

Tony was dreadfully miscast in the part. He was too heavy for it; it required a much lighter touch. It was a part that Jack Lemmon or James Garner should have played, essentially. Cukor wanted a young English actor nobody had ever heard of by the name of Roger Moore. Of course, no one was going to give him Roger Moore.

In fairness to Tony, he didn't have the pages. He couldn't go home and read the script and work on his character. Nobody knew what they were getting the next day. That was very tough on everybody.

I suppose Tony did do a very good job, considering; but he was a big pain in the ass during the shooting. Taking issue with this, not liking what he had to

do there. I remember at one point during a script conference with him, Sophia [Loren], George, and I don't know who else, George got so angry that he got down on his knees and started to salaam in front of Tony, because he was just so angry he didn't know what else to do. That defused the situation. It also defused George's own anger.

On the other hand, George was very courtly and very nice with Sophia, who was still not yet a star and very uncertain of the language.

What was your impression of Cukor?

I was enamored of George. I thought he was a wonderful man—a gent, extremely generous, funny, and bitchy.

I was entranced by that trio of Cukor, Huene, and Allen—Huene was a very elegant baron; Gene Allen was an ex-LA cop that Cukor found somewhere and brought to work for him, and was of a considerably developed aesthetic sensibility. Allen looked like a cop, talked like a cop, but Cukor was able to see what he had to contribute, and Gene was very, very valuable. Gene did all the camera setups; he walked through them and laid them out.

Did that strike you as unusual?

Not in that context, really. Because you never felt that he was doing something that Cukor couldn't do, particularly. Cukor was very smart that way; he didn't have an ego in that sense—he used whatever he could.

The best moment in the picture—when the Indians raid the trunk of costumes, a marvelous scene—that's really what George was interested in in the film. I wrote a lot of scenes that were shot but cut out of the movie, because when he finished it. Paramount didn't know what to do with it. It wasn't a typical western. I know they made George shoot a couple of action scenes that weren't in the original script. He had no interest in doing that, but he was very much a company guy: he knew he didn't have control; that was it and on to the next thing. Then Paramount cut it their way—which was to cut out all the quality and the character, and go to plot. The plot was ridiculous!

So I've always felt that picture—apart from the fact that what was really shot was, in script terms, first draft—fell between two schools. It wasn't really a straight, bang-up western, yet I'm very fond of the movie . . . when I look back on it, with my own subjectivity, I was so happy at the time. I had just recently been cleared of the blacklist, I was working on something I loved, and there I was on a movie set! I just saw everything in a glowing kind of way.

After Heller, you worked with Cukor twice again.

After Heller, I went to Europe for Ponti and got stuck in Vienna, rewriting some terrible, terrible thing [A Breath of Scandal ]—I think the only movie I ever took my name off—it was just awful. Michael Curtiz was the director, but [Vittorio] De Sica was really directing it, afterwards. Ring Lardner [Jr.] had just finished a version and left, so I got put on it. Every ten minutes, a very nice man who was Ponti's partner—Marcello Gerosi—would come to me and say, "Now, look, you've got to write in a part here for an Italian actress

. . . " I'd say, "Listen, this is taking place in the Vienna of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. How am I going to do that?" He'd say, "Never mind how. If you put the part in, we'll get six million lire from Italy . . . " They were putting the picture together that way. Curtiz was kind of in his dotage. He would leave the set, and De Sica would come in and direct behind his back. Also, De Sica had to be paid in cash at the end of every day for his gambling. It was just a terrible, ridiculous mess, and I couldn't wait to get out of Vienna.

Then the [Charles] Vidor company came to Vienna to film Song without End [1960], and Vidor died. Then George came to replace Vidor. I found out that George was in Vienna and called him just to say hello. He said, "As long as you're here, why don't you read this script?" He sent over the script, and I read it. I remember I said to him—he had Dirk Bogarde playing the lead— "My best advice to you is to get rid of Dirk Bogarde and get Sid Caesar. Then, just film the script." It was like a parody, just a terrible script. He said, "Would you stay and do some work on it?" I said, "No, I can't. I've got to get out of here, or I'll go crazy . . . " My wife-to-be was waiting for me in Paris.

The picture was being partly produced by Charles Feldman, the agent. Feldman's mistress, Capucine, was playing the lead in it, one of her first movies. George said to Feldman, "I want Walter. I need him to work on this picture. Go get him." Feldman came to Paris, found out where I was—turns out he was an old friend of the lady I was going to marry—and for the first and only time in my life, I was subjected to this great Hollywood wooing. Every night he took us out to the best restaurants, saying things like "Just do two weeks for me; I'll get you twice your pay"—the whole schmear. What's fascinating about it is that 99 percent of you is laughing at what is happening, but there's another one percent in the back of your mind that is saying, "Well, maybe, who knows? .. " Finally, I said yes to the two weeks.

It was very funny because we were supposed to have dinner with Feldman that night, which was a Friday, and as soon as I told him yes, two hours later I got a call back from him saying, "Geez, something has come up. I can't have dinner with you tonight . . . " The wooing was all over, finished.

Anyway, I went back to Vienna and met with George. I said, "Look, there's nothing much we can do in two weeks ... let's just go through the script step-by-step on the basis of what you have to shoot first, and we'll just fix the scenes as best we can, and make them less egregiously awful." He said, "Absolutely."

I remember the first scene I started on was a scene between Wagner and Liszt. I rewrote the scene and brought it to him. He said, "It's not right." I said, "I know it's not right, but it's better, isn't it?" He said, "It's better, but it's not right." I said, "But it's better; let's keep going." Iended up spending two weeks on that one scene—really,in this terrible picture where there is only this one very well-written scene. George couldn't let it go. He was fascinated by it. It hurt him to let it go.

We would meet in the morning in his hotel room. I remember getting a big basket of marvelous fruitcakes—he would eat all of his and then take mine— talking about that scene. Maybe one reason why actors liked George so much is that he was marvelous with a scene, getting all the values out of that scene, whereas he was not great in the overall conception or arc of the script. That may be one of the reasons why he was so good in the studio setup. The studios knew how to use him; he did his best work under the aegis of the studio. As soon as he had to choose his own material and become a producer-director or something else, I think he was a little bit lost.

The only other time I worked with George was on the last Marilyn Monroe movie. Something's Got to Give. I was on the picture about six weeks. I was rewriting it when it shut down. Although the original that it was based on was such a good movie [My Favorite Wife, 1940] that you wondered why they wanted to change anything.

I had read somewhere that they were looking for writers for this project at Fox. I called Lazar and said, "How about this situation?" He said, "I'll call Zanuck and get on it right away," but then I never heard anything from Lazar. So finally I just picked up the phone and called George. He said, "Are you free? That's great. Absolutely." I asked, "Didn't Lazar call you?" He said, "No." I called Lazar, and the deal was made.

Again, it was an impossible situation. What was interesting is that nobody really liked Monroe. I didn't like her, particularly; the one I liked was Dean Martin, who I thought behaved terribly well. He liked to swing his golf clubs, and I had heard about his drinking; but when he had to do something on the set, he was very professional. He wasn't an actor of the sort that Cukor was used to dealing with—Cary Grant and Jimmy Stewart, people like that—but I liked him.

Whereas Monroe was totally unreliable. Nobody knew what she was going to do. Cukor was very calm about her. Just terribly nice, always. Courteous. And optimistic. "It's gonna work, we're gonna do it . . . " I never saw the other side.

How was Cukor when it all came down?

Fatalistic. He'd been in that mill for a long time. I remember what [the director] Lewis Milestone said to me once—he was a great raconteur—he had one terrible story after another about Hollywood. I asked him, "How can you take this abuse? How can you live with this?" He looked at me with his marvelous hooded eyes and said, "How does an alley cat live in the alley?" Cukor had a little bit of that. He'd seen it all. He did his job and lived in his nice house . . .

After the blacklist ended and your credits resumed, you could have moved back to Los Angeles.

I had made the decision to live in New York. In certain ways, in terms of career, it was not a good decision. Perhaps I would have had a stronger career

if I had stayed in Los Angeles. I wanted to live in New York—it isn't just having grown up here—I guess it's that old cliche-feeling about living in Los Angeles. I don't know if I'd make the same decision now.

There weren't that many films that originated in New York. Most of them came from Los Angeles. But I always managed to get enough work. And those were the days when they would fly you back and forth for a story conference. I liked going out there and living for a month and playing tennis with my friends.

When I did The Molly Maguires, which I coproduced with Marty [Ritt], I went out there for cutting and postproduction, and was in California for six to eight months. When I did Little Miss Marker, I was there for a year and a half. So I've spent a lot of time there. But I was never of the place, and probably that didn't do me any good.

Because, ultimately, they realize that and resent it?

I think they do, in some kind of way. They want to know you're there. They want to know they can call your agent, and you'll be in the office in an hour. They want to know they have that kind of control over you: that you are part of their labor pool. Especially in those days. Less so, now.

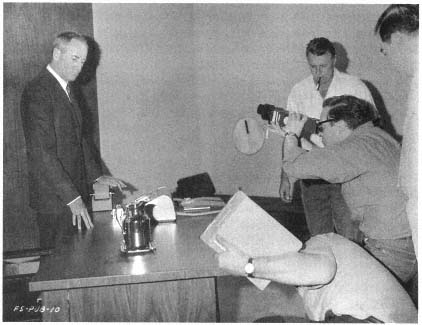

Sidney Lumet (looking through viewfinder) with Henry Fonda, filming Fail-Safe.

Apart from Cukor, for a long time in the 1960s and 1970s, it seemed as if you were virtually alternating films between Marty Ritt and Sidney Lumet. Was that deliberate . . . or coincidence?

Coincidence, really. Sidney works continuously, one thing after another, and basically, he doesn't tie himself to any one particular writer for very long. Whatever comes along that attracts him, or that he likes, he does.

Marty was, I think, much more politically oriented, as was I. I think that was the basis for Marty and I working together. Sidney would also do socially oriented movies, but Marty was always looking for material that had some kind of strong political or moral base. That is also a side of the street that I work—I like to do entertainment films that have some kind of social content.

Did you consciously choose that venue for yourself after the blacklist? Or is that just the way things developed?

It's the way things developed, but also the way I was. The way I am. And after a while, people chose me for that, if indeed they ever wanted that particularly, which they never did.

I remember visiting a prison art class once and speaking to the teacher. He told me that when prisoners are first learning and feeling their way as artists, they draw very harsh and realistic scenes of their daily lives: prison walls and steel bars, fellow convicts. Then, when they get past that stage and begin to explore their talent, they cut loose and draw almost any fantastical thing they can imagine. Can it be that, after the long years of the blacklist and writing under fronts, you were slowly emerging from a kind of mental prison?

It may have been. I never thought about it that way, particularly. I probably felt that is what I should be doing—that kind of material.

Were films like Paris Blues, Fail-Safe, and The Molly Maguires a struggle to get made, or was the struggle somehow easier in the 1960s, when it came to socially conscious films? Did the political context of the 1960s make those subjects more feasible?

I think so. But in the cases of both The Molly Maguires and he Front, those films wouldn't have gotten done unless we attached stars to them.

I saw Fail-Safe again recently and was struck by how breathtaking it is stylistically. Was it written that way?

That's Sidney. I wrote the script very quickly; then, Sidney directed it a lot like a television show. Sidney was always enormously adept technically, much more so than Marty really, much quicker with the camera. He tended to think in terms of the camera.

Sidney's camerawork can be bravura, whereas Marty's is more selfeffacing.

Sidney is much more related to the camera than Marty was. Marty's style was very unostentatious. Really, he was totally interested in and believed in the primacy of content. He was also very related, as was Sidney, to actors. Marty liked to put the scene up and let the actors go to work.

Did those differences affect how you wrote for one, as opposed to the other?

No. In Marty's case, how he worked tied in a lot to how I felt. Perhaps because my relationship has always been more to words than to the camera, I tend to write that way, concentrating on scenes for actors. I tend to write a very lean script. I very rarely put in a camera direction, mainly because what I found out rapidly—early on—was that the director paid no attention to my camera directions anyway.

Working with Marty and Sidney, two old friends, also guaranteed the integrity of the script. They usually knew how to get around the obstacles— whether the obstacles were the studio or some star.

Certainly. Sidney was always very resourceful, and Marty was a fighter. He fought for what he believed in. He wouldn't do anything that in some way he didn't believe in.

Whereas, when you worked away from them, you didn 't always have the same success, scriptwise. I am thinking of The Train. Another Burt Lancaster situation . . .

Well, Burt was running that show. It was a very unhappy experience. [The director] Arthur [Penn] and I were working on what we thought would be a very interesting movie about the tail end of a war and people who were fighting in the back lines. Then Lancaster fired Arthur after the first days of shooting. It was very unfair. It wasn't based on anything except whatever's Burt's feeling about Arthur may have been.

A personality conflict?

I think so, basically. I remember Lancaster coming over to Paris, where Arthur and I had a script meeting with him. He had read what I was doing, and he had ideas about the script and professed himself to be pleased with what was going on. I remember after I left the meeting, I was feeling very up about it, and Arthur said, "He [Lancaster] doesn't like me." I said, "What? He loves the script and . . . " Arthur had picked up on something I had not.

Unfortunately for the scheduling of the picture, the first scene that Burt had to do was a rather emotional scene with Michel Simon. I was there when they were shooting it, and Arthur was pushing him, as an actor, to go for certain things. Burt was resisting. At one point—I'll never forget this— Burt turned to Arthur and said, "Here, I'll give it the grin." He was saying, I'm not going to do what you want me to do. And shortly after, Burt fired him.

Was your script honored?

I'd been working on the script. By no means was it finished. Burt called me and said he would like me to stay on. I said I really didn't want to and finished out the week. He got some other writers working on it after that.[*] It was always the same story, and it's a good movie in certain ways, although Arthur

* Franklin Coen and Frank Davis are also credited for the screenplay of The Train.

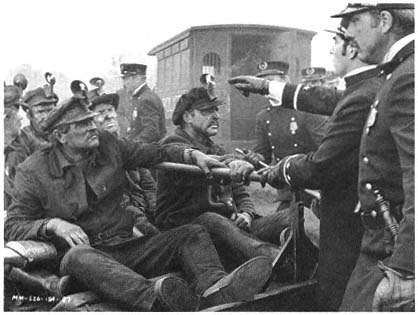

"One of the rare, pure experiences": Scan Connery (center) in The Molly Maguires.

had really set up all the scenes. But the film was disappointing. We were after something else, and as I say, I thought it was really unfair to fire Arthur not based on anything.

The Molly Maguires,[*]coming at the end of the decade, was really a highwater mark—and one of the few, serious films from Hollywood about organized labor—another being Norma Rae, also directed by Martin Ritt. What was the genesis of Molly Maguires?

I had always wanted to do something about the Molly Maguires, ever since I first read about them in college. I found there was very little written about them at all. They always intrigued me. I always had in the back of my mind the idea that the subject would make a great movie. I had talked to Marty about it. Then, when the opportunity came, we just grabbed it. At that time, Marty had clout, and we were able to make a deal.

* The Molly Maguires were "a secret society of Irish anthracite miners in east Pennsylvania (c.1854-77), which terrorized management and workers until with the help of Pinkerton's, the leaders were arrested and then hanged for murder" (The Merriam-Webstar Pocket Dictionary of Proper Names [New York: Pocket Books, 1970]).

That's the most surprising thing to me. It didn 't take a big effort to persuade the studio?

No. Paramount did it at a time when money was around. Where we got hurt was, Paramount produced several big-budget films around the same time; ours was the smallest, about a ten million dollar budget, I think. The others included On a Clear Day You Can See Forever [1970], Paint Your Wagon [1969], and a Harold Robbins film. The Adventurers [1970]. They were all initially unsuccessful at the box office, and Paramount made the corporate decision to dump them all, including Molly Maguires. It was never really allowed to find its audience, although over the course of time it has, of course, attracted a following. And I am certainly proud of the film. It was one of the rare, pure experiences.

All along, you had a hankering to write comedy. Why did you put it off so long? At -what point, after your long string of serious dramatic credits, did you feel a lessening of the dramatic impulse?

Well, you're right, I had always wanted to do a comedy. Humor was very much a part of me. In college I was editor of the humor magazine. Even in high school, I wrote a humor column for the school newspaper. It was always there. I just kept it down. I didn't think it was serious, just as nobody thought going to Hollywood was serious. If you were going to be a writer, you should write plays or novels.

But for a long time, Marty and I had been talking about doing something about the blacklist. We wanted to do a straight dramatic story about someone who was blacklisted. We could never get anybody interested at all. It wasn't until we came up with the idea of a front and making it as a comedy that we were able to get the film done. The Front became my first true comedy.

When I spoke to Marty, he seemed to feel the film should have been done dramatically, and that the comedy aspect was a compromise.

I don't agree with him, really. The idea that you can't be serious in a comedy, I don't agree with.

I think what he actually said is that you and he were having some trouble licking it as a drama.

I don't think that was the question. I think we could have licked it in a formal sense, in a conventional sense; but it soon became apparent that nobody was going to produce it. We couldn't get anything going there. I'm glad we did what we did.

Did the idea of writing it as a comedy come before the idea of putting Woody Alien in the film as the star?

Yes. We went to David Begelman, who was the head of Columbia then. Being the kind of perverse guy that he is, David gave us some money to do a first draft. It was only after we had a first draft that discussions began about a star. We talked about Dustin Hoffman, A Pacino, or Warren Beatty. Certainly, I saw somebody in the role who was not a conventional leading man. I

remember, we were talking about it, and Marty said, "What about that . . . kid?" I said, "What kid?" He said, "Woody Allen." I said, "What a very interesting idea." So we sent the script to Woody, and he said yes.

It was a very happy experience for all of us. Whether he would acknowledge it or not. Woody got a great deal from Marty in terms of his acting. He was on the film purely as an actor. He didn't write anything. He only contributed a couple of jokes. The one time he tried something on the picture was the sequence at the end [of the film] where he's testifying before the committee. We shot the scene and looked at the dailies, then decided we should make it funnier than it was. Woody said, "Let's shoot it again, and let me improvise." Marty set up the camera, and Woody improvised. He was hilarious. Only it had nothing to do with the picture. It was like ten minutes of stand-up comedy. Reluctantly, we couldn't use it.

In some way, I think that picture released me, because I could do comedy after that. I loved doing Semi-Tough, which was really a social satire—not just about football. Things like The Molly Maguires and The Front, which came from scratch, are very important to me and mean a lot to me. But so does Semi-Tough, although it came from a book [Semi-Tough, by Dan Jenkuis (New York: Atheneum, 1972)]. [The director] Michael [Ritehie] and I threw out the story and wrote one of our own. Michael and I did our own movie, just like Marty and I did our own movies.

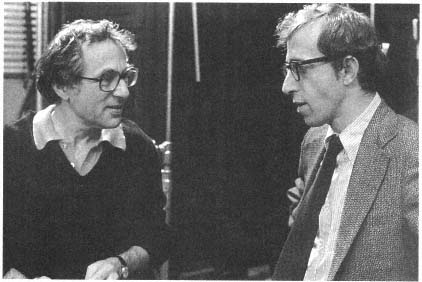

"My first true comedy": Walter Bernstein and Woody Allen on the set of The Front.

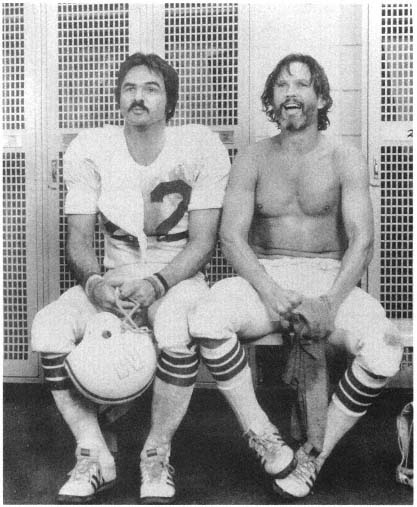

Burt Reynolds and Kris Kristofferson in a scene from Semi-Tough.

Michael and I developed a good relationship and wrote other comedy scripts—one was an anti-FBI satire; another was a satire on radio psychologists. But we couldn't get them produced.

How do you feel about Yanks?

I love Yanks . I wish it had been twenty minutes shorter. The texture of the movie is what the movie is about—the look of it, the sense of it. The story

itself is commonplace, soap operaish. [The writer] Colin Welland had worked for a number of years getting the film made. The story is about where he was coming from; he's really the kid in the story. I did the American stuff; essentially, that is all I did.

I think it has one piece of bad casting in it: William Devane, who is a good actor. He's not right for the part. But everybody else is so good.

Why did they come to you to help on the script?

I think because I had been in the war and had those credentials. I did use a lot of my own experience although I had not been in England. And I liked working with [the director John] Schlesinger. I thought he was very much like Cukor—in his sensibility and in something which they shared: for both of them, the total arc of the picture was where they were weakest. On the details, the scene itself, the visualization of the scene, the texture, they were wonderful.

When I see that picture, Yanks, I'm always moved by it. I don't know how much of it is my own nostalgia. But there's something lovely about it.

Why did you end up directing Little Miss Marker? An offer you couldn't refuse?

Essentially that's what happened. There were a lot of personal reasons that went into it. I was asked to write the script. I didn't think there was a chance to direct, but I said I would write it if I could direct it.

Is that something you had been saying again and again for years?

No. I'd been thinking it, never saying it.

Who did you say it to this time—who answered yes?

Jennings Lang—lovely, lovely man. His attitude was, I've set a lot of firsttime directors loose in the business; you may as well be another one.

Before I started directing, I called all my director friends and asked their advice. I got all kinds of totally different advice. I called Cukor, and he said, "Ah, don't worry. It's nothing . . . " I said to Michael Ritchie, "I don't know where to put the camera. Where do I put the camera?" He said, "Ah, don't worry about it. Wherever you put it, it will be all right." I called Schlesinger, and he said, "Coverage! Coverage! Just be sure you get enough coverage." None of the advice helped.

Were you insecure about directing?

Yes, I was very tentative about it, in part because it coincided with a difficult time in my personal life. I was never able to emancipate myself from that. But I didn't think it through enough. I winged it too much. I made a lot of mistakes. I look at it now, and I'd like to start that picture all over again. It was the kind of picture that needed a lot more style than I was prepared to give it.

Theatrical style? Visual style?

Both. It needed a very strong style imposed on that picture—a Preston Sturges style. I did it much too conventionally.

Did you make the major casting decisions?

Not totally. I had [Walter] Matthau to begin with, which was wonderful. For the female lead, I chose Julie Andrews because I thought I could get something from her which in fact I was unable to get. I thought I could get some kind of mix between her and Matthau, but it didn't work, possibly my fault or possibly because there wasn't any chemistry there.

Was it also a failure on your part to relate to the actors?

No. I feel that I can relate to actors, but I think I cast it wrong. I cast Tony Curtis where I should have cast Jack Palance. I cast Julie Andrews where I should have cast Angie Dickinson. I went the wrong way. Both Tony and Julie were quite good but not quite right.

The House on Carroll Street was another partial failure. I like it, but it should have worked better. It's a good idea—a blacklist drama with Hitchcockian overtones. What went wrong?

Like The Molly Maguires and The Front, it was an original and meant a lot to me. But you're right; it didn't turn out so well. I'm not happy about it.

I gather your script was different from the eventual movie.

The original script was good—and it was the script that I started out to write. The script that was shot was also my script, however. There's nothing in it that isn't mine, so I can't very well say they took it and changed it. But it got unfortunately watered-down and became kind of a one-note thing that happens to have unfelicitous casting. It doesn't work.

In general, I've been very lucky with directors about my scripts. None of them ever wanted to write or to direct their own stuff. With Sidney, he'd read the script, he'd have very strong ideas about certain things, and that would be it. Marty would always spend more introspective time on a script. The difference is also in their personalities and their characters. Michael's full of ideas. Sidney's responses are very quick. Marty was always slower, he thought more, chewed it around.

On The House on Carroll Street, I am tempted to say to people . . . there was more to the original script . . . there was a scene that should have been there and is out . . . and there's a scene they shot, which they didn't use. But I feel terrible doing that. I hate myself for it.

A complicated question: After 1972, you did not work with either Sidney or Marty again. Or, at least, nothing came to fruition. Why?

It just happened. With Sidney, as I say, he goes from one project to another very quickly. But Marty and I were always talking about doing something. We were always in process. It was not that easy for us to find material, or rather, the kind of material we wanted to do was not that easy to get produced. But we were always talking about something, and in fact, before he died we were talking about a particular project—a complicated political story about the end of communism. I'm sorry about the things we never did do.

The 1990s is actually your fifth decade of writing movies. Do you find a Hollywood that you can relate to, receding from grasp?

I really try not to fall into the nostalgia trap and say, "Gee, it was better twenty years ago." One of the last times I had dinner with Marty, he was saying that he felt, in his experience there of the last thirty years, that he has never seen studio executives more incompetent, venal, or corrupt than now. But I don't have that much to do with people in Hollywood. I find it depressing when I have to go out there and meet with them. I never found it exhilarating, particularly. I do find the standards lower. I really do. I find the standards of literacy lower—film literacy, let alone intellectual literacy. There was never, in my experience, this marvelous Golden Age where all that was done was so sacred. And I feel Hollywood today reflects where this country has been going for the last eight, ten, fifteen years. Why shouldn't it?

The old-boy networks and executive relationships have sure changed.

Oh yeah. Also, they're all interchangeable. It's fascinating. Some years ago, I went out to Los Angeles to pitch story ideas. My agent set up meetings with Mike Medavoy, Jeff Katzenberg, and Ned Tanen—whoever. You have these meetings with them and always their two assistants. At the end of the day, I couldn't remember who was who of the assistants. With beards, without beards—whatever. Depressing. They're bright but interchangeable . . .

Yet you persist in the field . . .

It's where I make my living . . .

Is that the only reason? You could do a Sidney Sheldon and write novels?

. . .

I love movies. I love movies. I still get that frisson when I go on a movie set—the most boring business in the world—but I feel that same thing I felt when I walked on the lot of Columbia in '47: I'm here! It's always meant that to me. I've always wanted to be part of making movies.

Which movies are enduringly happy memories for you—more successfully yours?

The originals—The Molly Maguires and The Front; Semi-Tough; even though the credit is shared with Collin [Welland], Yanks, which I feel very strongly about; and Fail-Safe. The good ones. But the ones that are not so good I feel are mine too, in the sense that I can't point to any of the ones I've done and say, Well, somebody crapped up my script, because that's not me up there.

I accept the cooperative nature of filmmaking. It's one of the things that attracts me to movies, that idea. I love working with other people, so that I never feel, or have never felt—maybe it's a lack of ego—bitter. I accept the nature of that beast—not just accept it, I like it. When I'm working with people I respect, who add creatively to the whole of the thing, I find it exhilarating. I'm a sucker for any kind of communality or community, anywhere but especially, when it's working well, within a film.