Plates

Plate 1

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Franz Heinrich Corinth with a Wine Glass , 1883.

Oil on canvas, 107 × 88 cm, B.-C. II. Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich (G2275).

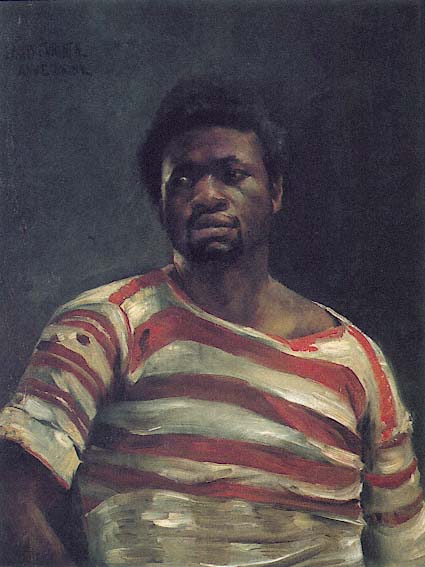

Plate 2

Lovis Corinth, Negro ("Un Othello") , 1884. Oil on canvas, 78.0 × 58.5 cm,

B.-C. 19. Neue Galerie der Stadt Linz, Wolfgang-Gurlitt-Museum (23).

Photo: M. Sirotek Fachlabor.

Plate 3

Lovis Corinth, Franz Heinrich Corinth on His Sickbed , 1888. Oil on canvas,

61.5 × 70.5 cm, B.-C. 57. Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt (SG 1182).

Photo: Ursula Edelmann.

Plate 4

Lovis Corinth, Diogenes , 1891. Oil on wood, 178 × 208 cm, B.-C. 86. Museum

Ostdeutsche Galerie Regensburg (3470).

Photo: WS-Meisterphoto Wolfram Schmidt.

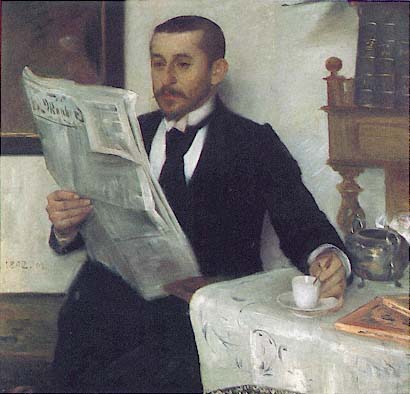

Plate 5

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of the Painter Benno Becker , 1892. Oil on canvas,

87 × 92 cm, B.-C. 99. Von der Heydt-Museum der Stadt Wuppertal,

Wuppertal-Elberfeld.

Plate 6

Lovis Corinth, Slaughterhouse , 1892. Oil on canvas on cardboard,

34 × 41 cm, B.-C. 87. Kunsthalle Bremen (391-1921/7).

Plate 7

Lovis Corinth, View from the Studio , 1891. Oil on canvas, 60.5 × 88.5 cm,

B.-C. 84. Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe (2302).

Plate 8

Lovis Corinth, Fishermen's Cemetery at Nidden , 1894. Oil on canvas, 113 × 148 cm, B.-C. 115.

Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich (12043).

Photo: Blauel/Gnamm-Artothek.

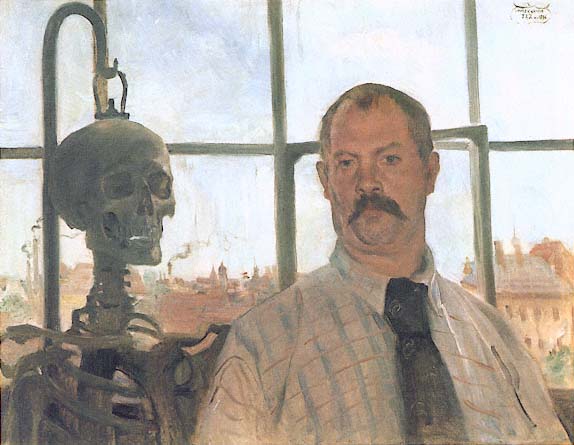

Plate 9

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait with Skeleton , 1896. Oil on canvas, 66 × 86 cm, B.-C. 135. Städtische

Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich (G2075).

Photo: Joachim Blauel-Artothek.

Plate 10

Lovis Corinth, In Max Halbe's Garden , 1899. Oil on canvas, 75 × 100 cm, B.-C. 185.

Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich.

Photo: Joachim Blauel-Artothek.

Plate 11

Lovis Corinth, Reclining Female Nude , 1899. Oil on canvas, 75 × 120 cm, B.-C. 179.

Kunsthalle Bremen (187-26/1).

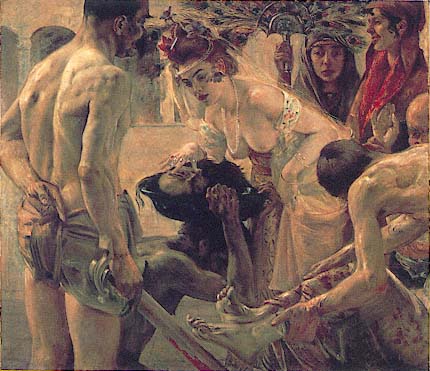

Plate 12

Lovis Corinth, Salome , 1900. Oil on canvas, 127 × 147 cm, B.-C. 171. Museum

der bildenden Künste zu Leipzig (1531).

Photo: Chr. Sandig.

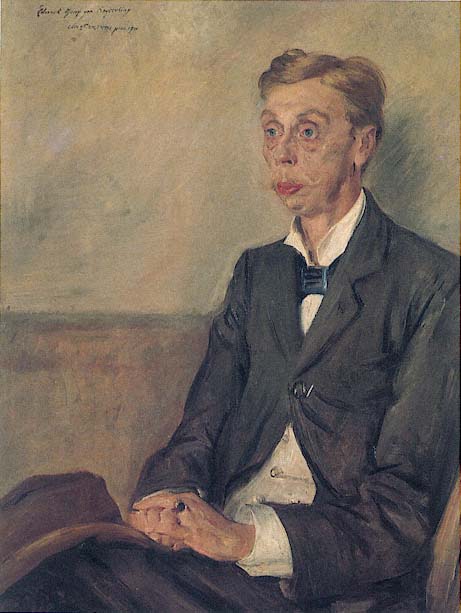

Plate 13

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Count Eduard Keyserling , 1900. Oil on canvas,

99.5 × 75.5 cm, B.-C. 205. Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich (8986).

Photo: Joachim Blauel-Artothek.

Plate 14

Lovis Corinth, Donna Gravida , 1909. Oil on canvas, 95 × 79 cm, B.-C. 394. Staatliche

Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Nationalgalerie, Berlin (West) (A II 143/Kat. 1262).

Photo: Jörg P. Anders.

Plate 15

Lovis Corinth, The Family of the Painter Fritz Rumpf , 1901. Oil on canvas, 114 × 140 cm,

B.-C. 219. Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Nationalgalerie, Berlin (West) (A II 596).

Photo: Jörg P. Anders.

Plate 16

Lovis Corinth, Rudolf Rittner as Florian Geyer , 1906. Oil on canvas, 180.5 × 170.5 cm,

B.-C. 327. Von der Heydt-Museum der Stadt Wuppertal, Wuppertal-Elberfeld.

Plate 17

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait as a Howling

Bacchant , 1905. Oil on canvas, 67 × 49 cm,

B.-C. 304. Insel Hombroich.

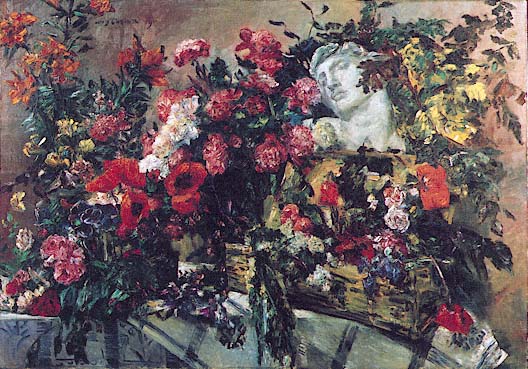

Plate 18

Lovis Corinth, Hymn to Michelangelo , 1911. Oil on canvas, 138 × 199 cm, B.-C. 481.

Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich (FH 271).

Plate 19

Lovis Corinth, After the Bath , 1906. Oil on canvas, 80 × 60 cm, B.-C. III.

Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg (2375).

Photo: Elke Walford.

Plate 20

Lovis Corinth, Emperor's Day in Hamburg , 1911. Oil on canvas, 70.5 × 90.0 cm, B.-C. 483.

Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Cologne (WRM 2585).

Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv.

Plate 21

Lovis Corinth, Storm at Capo Sant'Ampeglio ,

1912. Oil on canvas, 49 × 61 cm, B.-C. 537. Staatliche

Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Neue

Meister (2580 G).

Photo: Sächsische Landesbibliothek Abt.

Deutsche Fotothek/Heselbarth.

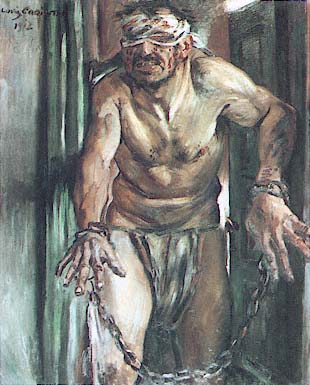

Plate 22

Lovis Corinth, Samson Blinded , 1912. Oil on canvas,

130 × 105 cm, B.-C. 520. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin,

National-Galerie (DDR) (5873).

Plate 23

Lovis Corinth, Still Life with Lilacs , 1917. Oil on

canvas, 55.2 × 45.0 cm, B.-C. 718. The Detroit Institute of

Arts (Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Hermann Pinkus) (79.159).

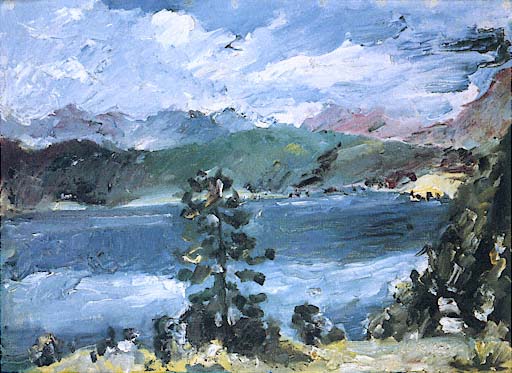

Plate 24

Lovis Corinth, October Snow at the Walchensee , 1919. Oil on

wood, 45 × 56 cm, B.-C. 772. Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe.

Plate 25

Lovis Corinth, The Walchensee in Moonlight , 1920. Oil on

wood, 18 × 26 cm, B.-C. 807. Pfalzgalerie Kaiserslautern (53/2).

Plate 26

Lovis Corinth, Walchensee , 1920. Oil on wood, 18.5 × 22.0 cm, B.-C. 806.

Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg.

Photo: Elke Walford.

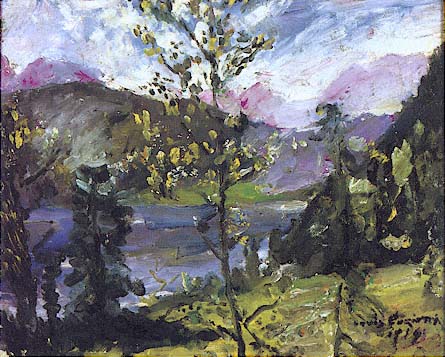

Plate 27

Lovis Corinth, Walchensee: View of the Wetterstein , 1921. Oil on canvas, 90 × 119 cm,

B.-C. XIII. Saarland Museum Saarbrücken, Stiftung Saarländischer Kulturbesitz (1505).

Photo: Gerhard Heisler.

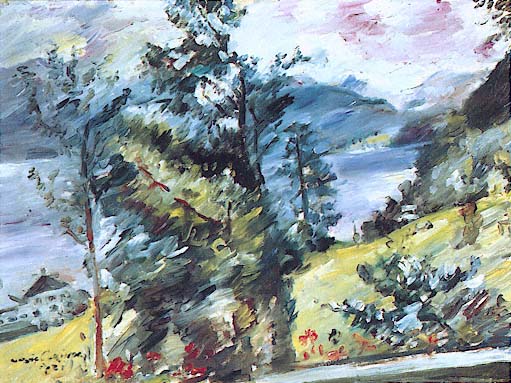

Plate 28

Lovis Corinth, Walchensee with Larch , 1921. Oil on canvas, 64 × 88 cm, B.-C. 832.

Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Nationalgalerie, Berlin (West) (1381/A II 366).

Photo: Jörg P. Anders.

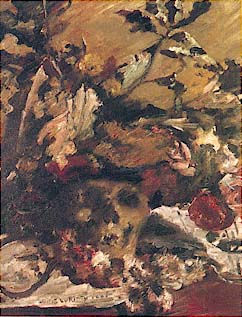

Plate 29

Lovis Corinth, Still Life with Flowers,

Skull, and Oak Leaves , 1921. Oil on canvas,

91 × 71 cm, B.-C. 821. Leopold-Hoesch-

Museum, Düren.

Plate 30

Lovis Corinth, Flowers and Wilhelmine , 1920. Oil on canvas, 111.0 × 150.5 cm, B.-C. 795.

Öffentliche Kunstsammlung Basel, Kunstmuseum (1741).

Photo: Hans Hinz.

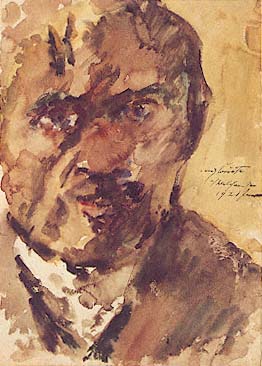

Plate 31

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait , 1921. Watercolor,

39 × 29 cm. Ulmer Museum, Ulm (BW 1967.57); on

permanent loan from the State of

Baden-Württemberg.

Photo: Bernd Kegler.

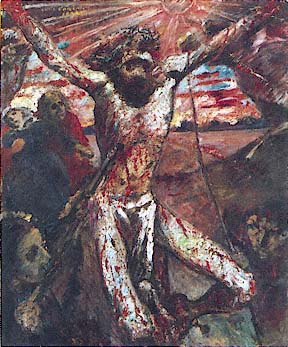

Plate 32

Lovis Corinth, The Red Christ , 1922. Oil on wood,

135.7 × 107.7 cm, B.-C. XV. Staatsgalerie moderner

Kunst, Munich (12383).

Photo: Joachim Blauel-Artothek.

Plate 33

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of the Painter Leonid Pasternak , 1923. Oil on canvas,

80 × 60 cm, B.-C. 913. Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg (2941).

Photo: Elke Walford.

Plate 34

Lovis Corinth, Birth of Venus , 1923. Oil on canvas on cardboard,

50 × 40 cm, B.-C. 920. Galerie G. Paffrath, Düsseldorf (0282).

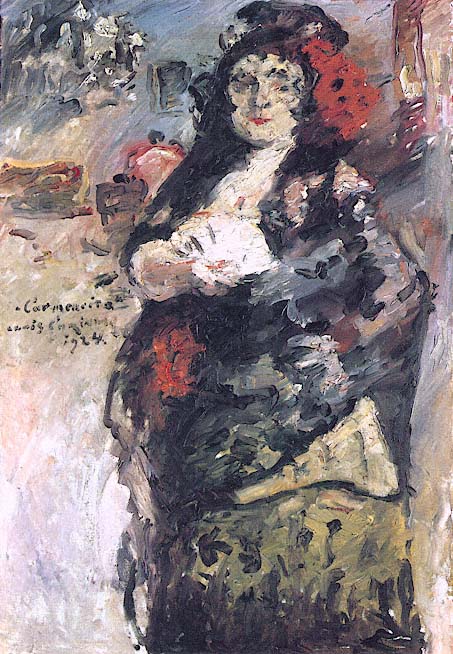

Plate 35

Lovis Corinth, Carmencita , 1924. Oil on canvas, 130 × 90 cm, B.-C. 961.

Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt (2064).

Photo: Blauel/Gnamm-Artothek.

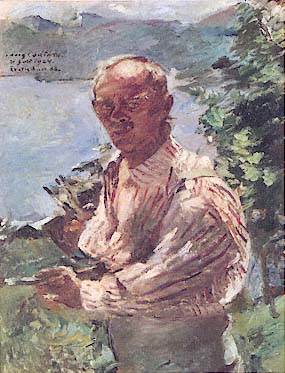

Plate 36

Lovis Corinth, Large Self-Portrait at the Walchensee ,

1924. Oil on canvas, 137.7 × 107.7 cm, B.-C. VII.

Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen,

Munich (11327).

Photo: Joachim Blauel-Artothek.

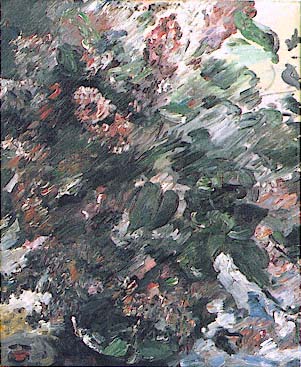

Plate 37

Lovis Corinth, Larkspur , 1924. Oil on canvas,

100 × 80 cm, B.-C. XXI. Bayerische

Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich (9219).

Photo: Joachim Blauel-Artothek.

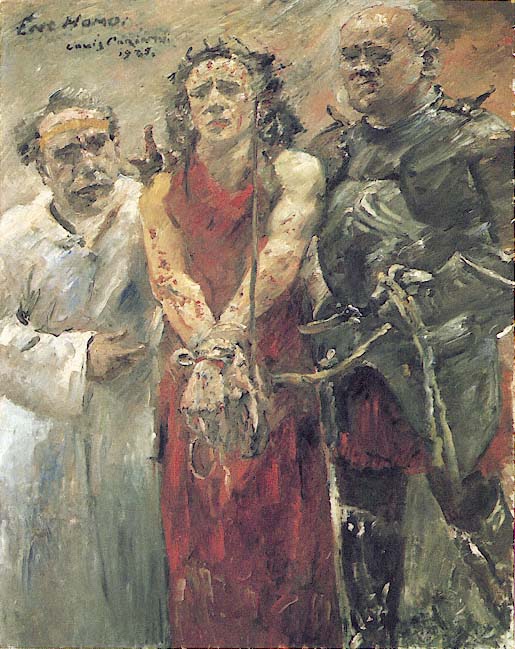

Plate 38

Lovis Corinth, Ecce Homo , 1925. Oil on canvas, 190.5 × 150.0 cm, B.-C. XXII. Öffentliche

Kunstsammlung Basel, Kunstmuseum (1740).

Photo: Hans Hinz.

Plate 39

Lovis Corinth, Thomas in Armor , 1925. Oil on canvas, 100 × 75 cm,

B.-C. VIII. Museum Folkwang, Essen (309).

Plate 40

Lovis Corinth, Last Self-Portrait , 1925. Oil on canvas, 80.5 × 60.5 cm,

B.-C. I. Kunsthaus Zurich (1867).

Except for his Kitchen Still Life from 1889 (B.-C. 68), Corinth's early still lifes are small and simple: a few pieces of fruit arranged in a dish or on a napkin; a glass with a flower or two. But he reveals a distinct preference for the exotic that endows even the least pretentious still life with a touch of splendor. Sea shells, a pineapple, or a grapefruit, cut open, often enrich an otherwise modest arrangement. Similarly, blossoms of unusual form and size, such as azaleas, chrysanthemums, roses, lilies, gladiolus, and amaryllis, are predominant in the flower pieces.

From 1908 on Corinth's still lifes increased in size and became more ambitious in conception as he evidently sought to invest them with the importance previously reserved for his portraits and figure compositions. In an example from 1910 (Fig. 107) rare objects have been juxtaposed on a white damask cloth: a Chinese figurine painted in delicate flesh tones and tints of pale blue edged in gold, a small bronze Persian statuette of a dog, a pitcher of burnished copper, and, behind them all, a fragile Murano vase, pearl gray and dark blue. The two pink lilies in the vase gracefully round out the composition at the top. This painting is closely related to two other still lifes with oriental statuettes, one also dated 1910 (B.-C. 448), the other 1911 (B.-C. 449), both painted at the specific request of a Berlin collector. The commission no doubt helped to convince Corinth of the value of such pictures, which could, moreover, further enhance his reputation.

A splendid still life with game (B.-C. 443) of 1910 served as a prelude to a large canvas (Fig. 108), nearly five by seven feet—which was the first still life Corinth exhibited at the Berlin Secession. As if to lend respectability to the undertaking, he assured himself of the authority of tradition. The painting recalls not only Max Liebermann's ebullient Kitchen Still Life with Self-Portrait from 1873 (Städtische Kunstsammlungen, Gelsenkirchen) but also the works of Frans Snyders, which often similarly juxtapose living persons and nature morte . The dead fowl, game, vegetables, and bowls of fruit are common details in works from the Flemish master's studio, as is the two-tiered arrangement, which Corinth enlivened with the diagonal axis of the table. He thus created an impression of movement that is further intensified by the figure of Charlotte Berend, who holds aloft a spray of narcissus with one hand and reaches for a bouquet of roses with the other. A similar energy pervades the brushstrokes, which unify the pictorial field and underscore the baroque exuberance of the conception. The festive mood made the painting an ideal gift for Charlotte Berend, to whom the canvas is specifically dedicated, partly in honor of her thirty-first birthday, partly to compensate her for the loss of the large family picture from 1909 (see Fig. 89), which Corinth had originally

Figure 107

Lovis Corinth, Still Life with Buddha , 1910. Oil on canvas,

47 × 47 cm, B.-C. 438. Private collection, Berlin.

Photo courtesy Bernd Schultz.

given to her but subsequently sold to a Berlin collector. The 1911 painting too, however, was sold soon after being exhibited at the Berlin Secession.

In recompense, Corinth immediately set to work on another, similarly large, still life for Charlotte, a sumptuous flower piece bearing the poetic title Hymn to Michelangelo (see Plate 18), in allusion to the plaster-cast head of the sculptor's Dying Slave that emerges from an array of roses, poppies, irises, and carnations. Although most of the flowers are recognizable, in this canvas Corinth disregarded the principle on which—according to his own teaching manual—still-life painting should be based, namely, the characterization of individual textures. The fluid application of the paint, often in thick blobs twisted and turned with the brush, lends the vivid colors a life independent of the forms they ostensibly describe. As a result, this still life is less a painting of flowers than a depiction of a process that conjures up the very idea

Figure 108

Lovis Corinth, Large Still Life with Figure ("Birthday Picture "), 1911.

Oil on canvas, 150 × 200 cm, B.-C. 463. Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Cologne.

Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv.

of flowering. The mournful statue, in contrast, and the cut flowers translate what is otherwise a jubilant evocation of nature into a poignant memento mori .

A similar development from a specific circumscribed view to a unified, visceral expression is also seen in Corinth's landscapes and in his paintings whose human figures are integral parts of the landscape—always excepting his open-air portraits, where the need for verisimilitude would have interfered with a more generalized rendering of the sitter. Corinth's early landscapes include urban views, forest interiors, open fields, and scenes near brooks, lakes, and the sea. In conception and execution they range from the naturalism of the Barbizon and Leibl schools to evocative landscapes in the Romantic tradition. A more unadulterated pleinairism was the result of Corinth's early years in Berlin. Unlike the French Impressionists, however, who through

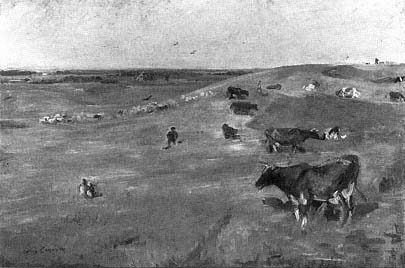

Figure 109

Lovis Corinth, Cow Pasture , 1903. Oil on cardboard, 67.5 × 99.7 cm,

B.-C. 268. Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum, Landesgalerie,

Hannover (KM 135/1949).

a vibrating texture of brushstrokes sought to re-create the atmospheric character of a given day, even a given time of day, Corinth opted for a broader and more simplified execution that gives the impression of movement and light without dissolving the image into a myriad of colored particles.

In a landscape with cows (Fig. 109), painted in the summer of 1903 at Brunshaupten, near the Baltic seacoast, the details of the view are subordinated to sweeps of color that describe the low-lying terrain while investing it with a gentle rhythm that seems to extend beyond the confines of the frame. The ductus of the brush itself conveys the essential character of the landscape. That the problems of plein air painting were for Corinth only relative is seen even more clearly in After the Bath (see Plate 19), a work completed in 1906 during an excursion to Lychen, in Brandenburg, and executed, in typical Impressionist fashion, while Corinth was seated in a boat. Here the textures are subordinated to a whirlwind of colors—now ebbing, now flowing—in bursts of resurgent energy. Although the painting ostensibly depicts Charlotte Berend after a swim in a pond, this is, above all, a quintessential painting of

Figure 110

Lovis Corinth, Inn Valley Landscape , 1910. Oil on canvas,

75 × 99 cm, B.-C. 441. Staatliche Museen Preussischer

Kulturbesitz, Nationalgalerie, Berlin (West) (NG 1263; A II 263).

Photo: Jörg P. Anders.

summer that transcends both the identity of the sitter and the topography of the site. In 1910 Corinth applied a similar breadth of execution to his first great mountain view, the Inn Valley Landscape (Fig. 110), in which simplified horizontal and diagonal bands of terrain gradually lead the eye into the distance. The all-pervasive bluish light of the river valley further helps to unify the composition.

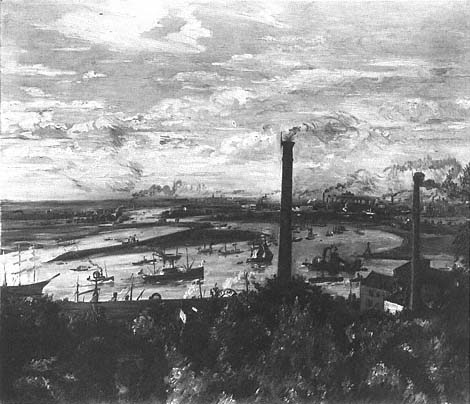

Three paintings completed in the late summer of 1911 in Hamburg are high points among Corinth's landscapes. They were painted on the initiative of Alfred Lichtwark, director of the Hamburg Kunsthalle, who was assembling a cycle of pictures specifically devoted to the Hanseatic seaport, comprising views of the city and its surroundings and portraits of influential men and women born or active in Hamburg. Lichtwark eventually selected for the Kunsthalle the view of the Köhlbrand (Fig. 111), the sprawling estuary of the Elbe River as seen from the suburb of Altona. It was a fitting choice, for the painting depicts the very lifeline on which the city's prosperity depended.

Figure 111

Lovis Corinth, View of the Köhlbrand , 1911. Oil on canvas, 114.5 × 135.0 cm,

B.-C. 482. Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg (1964).

Photo: Ralph Kleinhempel.

The majestic river winds through the countryside, bearing a flotilla of sailboats, steamers, and barges. The smokestacks in the foreground and near the horizon bear witness to the harbor's industrial might. Adopting a pictorial formula first developed by such sixteenth-century Flemish masters as Patinir, Corinth conveyed through the panoramic view something of the outward-looking character that had shaped the city's economic development for centuries.

In two smaller landscape views from across the basin of the Alster River, the tributary that links the city with the Elbe, Corinth silhouetted the old town center, decked out with flags and set for a display of fireworks. The occasion for the festivities was a visit of the German emperor and empress to Hamburg in late August to witness the beginning of the Ninth Army Corps' maneuvers on the parade grounds of Gross-Flottbeck. Despite the closely circumscribed view Corinth adopted in both works, the festive mood enveloping the city is emphasized more than topography. In the nocturne (B.-C. X), cascading fireworks and the sparkling lights of the city transform the Alster basin into a shimmering pond of red, blue, and gold. In the other painting (see Plate 20) the flags atop the buildings are so large that they have no plausible relation to the structures they surmount and even dwarf most of the church spires. It is as if the entire city were aflutter with excitement. The grayish blue light is almost palpable, so emphatic are the brushstrokes that give substance to the atmosphere.

Corinth's growing interest in still life and landscape was accompanied by an increasing emphasis on color, especially colored shadows, stimulated by a renewed acquaintance with the paintings of the French Impressionists, in particular those of Edouard Manet. Early in 1910 an important exhibition of French Impressionist paintings was organized in Berlin by Paul Cassirer, who together with the galleries of Durand-Ruel and Bernheim-Jeune in Paris had just acquired the prestigious collection of Auguste Pellerin. Many pictures by Manet were included in the show, notably such important works as The Luncheon in the Studio (1868; Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Neue Pinakothek, Munich), The Artist (Portrait of Marcellin Desboutin) (1875; Museu de Arte, São Paulo), Nana (1877; Kunsthalle, Hamburg), and A Bar at the Folies Bergères (1881–1882, Courtauld Institute Galleries, London).[67] Still, the nuances of mood and the essentially expressive content of Corinth's own mature still lifes and landscapes only serve to point out the inadequacy of the term Impressionism in characterizing his work.

The same can be said of such other German "Impressionists" as Liebermann and Slevogt, both of whom were similarly concerned with finding a

pictorial equivalent not only for what they saw but also for how they saw it. Their brushwork is sometimes ecstatic, sometimes lyrical, and usually a predominant tonality unifies and reinforces the mood of any given work. Liebermann explained his position in an essay first published in 1904 and entitled, somewhat ambiguously, "Die Phantasie in der Malerei." In it he spoke of the "artistic truth" with which the artist sees nature. For him fantasy in painting had to do not with subject matter but with the way technique successfully recreates in the viewer the sensation the artist experienced while executing the work. Though for Liebermann sensory perception was always the basis of the artistic process, only what the painter manages to extract from nature and renders visible makes him a true artist.[68]

For Slevogt, too, seeing was a selective process conditioned by the painter's disposition. In 1928 he commented on Liebermann's essay:

The eye is not an instrument like the mirror. The eye is a living conduit to our entire being. It is always self-conscious, always conditioned by some purpose— it is a sieve that allows many things to filter through in the process of seeing. The eye looks, it searches, and whatever it does not understand, it does not see. A hunter does not see like a sailor. Somebody who never hunts cannot see a rabbit even if it is sitting right next to him. The eye sees with much imagination, music, rhythm, and intoxication.[69]

Expanded Fame

Between 1909 and 1911 Corinth received several portrait commissions. Although these works are of uneven quality, they are a measure of the growth of his reputation, for in each case the commission originated outside Berlin. In 1909 he painted the portrait of Ludwig Edinger (B.-C. 398), then director of the Senckelberg Neurological Institute in Frankfurt. From Hamburg came commissions for the portraits of Albert Kaumann (B.-C. 431) and Henry Simms (B.-C. 432), both painted in 1910, and for the portrait of Frau Kaumann (B.-C. 485), which dates from 1911. The Hamburg commissions may have come about through the recommendation of Alfred Lichtwark, who was keenly interested in the history of portraiture in the Hanseatic city-state and had published a book on the subject in 1899, urging that the tradition be encouraged and continued.[70] Lichtwark also personally commissioned from Corinth a portrait of Eduard Meyer for the Hamburg Kunsthalle. Meyer was a professor of history at the University of Berlin and a native of Hamburg. For Corinth this

commission was particularly important since by 1910 the Hamburg museum owned twenty-nine paintings by Liebermann and one by Slevogt but none by Corinth himself. Correspondence about this commission shows the extent to which Lichtwark's own views influenced the painter.[71]

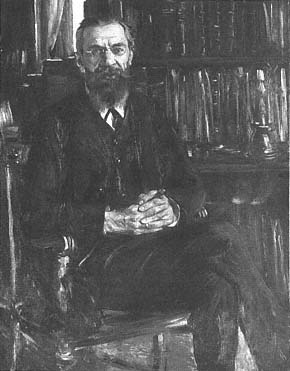

Lichtwark first approached Corinth about the Meyer portrait in November 1910. Since at the time Meyer was dean of the Philosophical Faculty at Berlin, Lichtwark suggested that the professor be depicted in academic dress standing by a large window in the dean's office, a suggestion that was not at all frivolous. Lichtwark clearly envisioned a portrait of some official character that would blend with other paintings already in the Kunsthalle collection, such as Liebermann's portrait of Mayor Carl Friedrich Petersen (1891) and Slevogt's portrait of Mayor William Henry O'Swald (1905), in both of which the sitters are depicted in their robes of office. As it turned out, Meyer rejected the idea as too pretentious and persuaded Corinth to paint him wearing an ordinary suit and in the privacy of his study (Fig. 112). Eduard Meyer (1855–1930) is seated nearly full-length before shelves filled with books, with what appears to be the corner of a window in an adjacent room at the upper left; the bright light entering from the right is reflected off the floor. Corinth made no effort to diminish the coarseness of Meyer's features, carefully emphasizing the facial characteristics, just as he attentively modeled the sitter's hands. Although the portrait ostensibly captures Meyer's habitual pose in casual conversation, there is a stiffness about the sitter that is reinforced by the restricted space and the well-ordered division of the background.

Corinth had completed the portrait by January 10, 1911, and a few weeks later sent it to Hamburg. Lichtwark was shocked when he first saw the painting and in a letter dated February 14 informed Corinth of his reaction. He was especially taken aback by the intensity of Meyer's gaze, and it seemed to him that the bright spot beneath the chair, in conjunction with the wall of books, virtually forced the sitter outside the picture frame. Although he acknowledged that he was gradually getting used to the portrait, he suggested that since Corinth now knew Eduard Meyer better, perhaps he could paint him a second time, but—as a pendant to the informal first portrait—wearing academic dress and standing by the large window in the dean's office, as first suggested. As an added inducement, it seems, Lichtwark in the same letter mentioned commissioning from Corinth a Hamburg landscape, a project that soon materialized (see Fig. 111).[72]

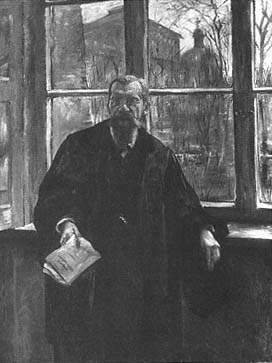

Meyer finally consented to Lichtwark's wish for a more "official" portrait, and Corinth began work on the second painting (Fig. 113) in late March. The

Figure 112

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Eduard Meyer , 1911. Oil

on canvas, 140 × 108 cm, B.-C. 498. Hamburger

Kunsthalle, Hamburg (1820).

Photo: Ralph Kleinhempel.

portrait follows Lichtwark's suggestions in virtually every respect. Meyer now wears a dark ultramarine academic robe; but his posture is relaxed, informal. Holding a velvet cap in one hand and a manuscript in the other, he leans on the windowsill in a moment of quiet concentration and reflection. The pages he holds add brightness to the lower left of the composition, balancing the bright expanse of the window.[73] Because window and wall no longer run parallel to the picture plane, as they do in the first portrait, the interior space seems more ample, and the large window extends the view out to a spring day enlivened only by a few specks of green and the pink of a bed of hyacinths. Knobelsdorff's elegant opera house on Unter den Linden and the cupola of St. Hedwig's Cathedral can be seen through the still-barren trees. Since the figure is illuminated from the back, Corinth was able to dispense with the details of individual forms, except for Meyer's head. With the summary treatment of the robe and the hands, however, the head acquires a spiritual strength that

Figure 113

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Eduard Meyer as Dean ,

1911. Oil on canvas, 198 × 150 cm, B.-C. 499.

Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg (1642).

Photo: Ralph Kleinhempel.

transfigures Meyer's countenance, lending him the dignity appropriate to his station in life.

Corinth considered the second Meyer portrait one of his best works, and Lichtwark was equally pleased. He not only followed through on the Hamburg landscape but also commissioned Corinth to paint yet another portrait for the museum's Hamburg gallery. The result was the huge portrait of Carl Hagenbeck (B.-C. 450), painted in October 1911. This portrait is not among Corinth's most successful works, largely because the big-game hunter and founder of the famous Hamburg zoo was forced to share top billing with one of his more spectacular charges, a fierce-looking walrus named Pallas. The painting is at best an interesting, though not entirely felicitous, contribution to the genre of the milieu portrait.

The Lichtwark commissions provide a rare glimpse into Corinth's financial transactions and reveal the prices he was able to obtain for his work at this

Figure 114

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Frau Luther , 1911. Oil on canvas, 115.5 × 86.0 cm, B.-C. IX.

Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum, Landesgalerie, Hannover (KM 137/1949).

time. The Hamburg Kunsthalle acquired the second Meyer portrait and the view of the Köhlbrand for 2,500 marks each and the Hagenbeck portrait for 4,000 marks—low prices Corinth apparently agreed to only because he was eager to see his work in a major museum. When they were exhibited at the Berlin Secession in 1912, the view of the Köhlbrand was insured for 10,000 marks and the Hagenbeck portrait for 20,000. Corinth informed Lichtwark at the time that he would gladly work for the Kunsthalle again, but only for substantially higher prices.[74]

Another impressive portrait from 1911, of Frau Luther (Fig. 114), the wife of Hermann Luther, a wealthy sugar importer of Magdeburg, demonstrates again how much the quality of Corinth's portraits depends on his psychological response to the sitter. As in the portrait of Eduard von Keyserling from 1900 (see Plate 13), similar to this one in form and conception, the figure is seen against a neutral ground, and Corinth relied on blue to unify the composition, although here the colors are more vivid. Clearly Corinth was fascinated by Frau Luther's elegant demeanor. Yet her stylish appearance in no way interferes with her psychological presence. On the contrary, the face is modeled and characterized carefully, even unsparingly, with special emphasis on the puffy skin around the eyes. The enlarged veins accentuate the sensitivity of the well-groomed hands. Frau Luther may wear her striking dress and hat with nonchalance and gaze at the viewer with the self-assurance of her class, but her proud bearing and splendid wardrobe only serve to highlight her frailty and the onset of physical decay.

Corinth's output during 1911 was prodigious. He completed at least sixty-three paintings and made sixty prints, including twenty-six color lithograph illustrations for the Song of Songs (Schw. L82) published by Paul Cassirer's Pan Presse. His paintings by now numbered more than five hundred works, and Georg Biermann was ready to begin work on the first monograph on the artist. But on December 11 of this year, his most productive thus far, Corinth was felled by a stroke.