Mommie Meanest: Narcissistic Moms and Neurotic Daughters

In a darker vein, the evil mother theme reemerges with a vengeance that much surpasses Charlotte Vale's almost quaintly Victorian misguided mother. No film typifies this image of the demon-

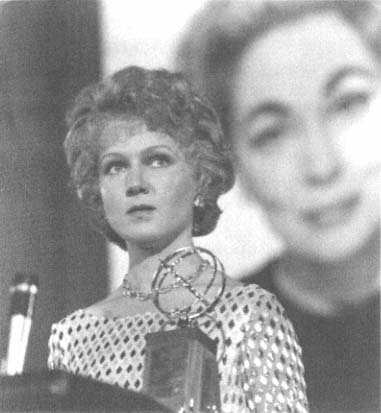

Fig. 25.

Evil mother Joan Crawford (played by Faye Dunaway) faces off against

persecuted daughter Christina in the grotesque vamp Mommie Dearest .

(Paramount Pictures, 1981; photo courtesy of Museum of Modern Art

Film Stills Archive)

ized mother better than Mommie Dearest (1981). Indeed, the wire hanger scene (in which the Crawford character brandishes a hanger in fury at her cowed daughter's neglect of her cleaning duties) has come to signify to daughters everywhere the violence behind the facade of maternal nurturance.

This film also points to what Nietzsche might have called eternal recurrence or Freud might have called the return of the repressed. For, in Mommie Dearest , Faye Dunaway portrays Joan Crawford as the evil mother incarnate, Crawford herself having played a less virulent version of this in one of the most famous (fictional) mother/daughter narratives of all time, Mildred Pierce . The star and the story, the person and the myth here merge to collapse both representational and historical distinctions. There are even scenes when Dunaway as Crawford rehearses lines from Mildred Pierce with her victim/daughter. All this is within the cinematic context of a film taken from an account written by Crawford's own daughter, Christina. This trope (tell-all biographies of evil star mothers written by angry daughters) seemed to become very popular in the 1980s. Crawford's daughter wrote the most famous one, but Bette Davis's daughter B. D. Hyman also wrote one (My Mother's Keeper ), as did Cheryl Crane, daughter of Lana Turner. The irony that all three of these real-life mothers played in famous mother/daughter films

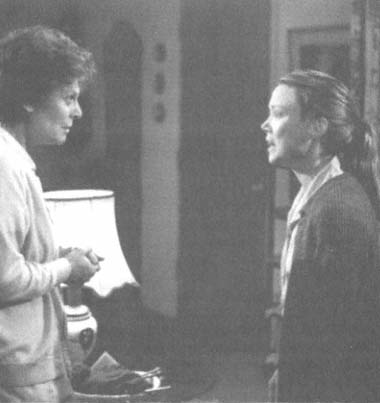

Fig. 26.

Even after death, mommie meanest looms ominously behind her newly

liberated daughter. (Paramount Pictures, 1981; photo courtesy

of Museum of Modern Art Film Stills Archive)

sorely tests any theory of the media that sees images as soundly set off from what we call "real life."[29]

The etiology of Joan's neurotic behavior is spelled out in the early moments of Mommie Dearest: her mother was bad, she had too many husbands, they were poor, she never had a father, so now she thinks she can "do it all" ("I never had a father. . . . I can be a father and a mother."). So Joan's evil is here, in true psychoanalytic fashion, referred back to her own slovenly mother and the lack of a father figure. This constant referring back (the "mommy did it to me" school of thought) is unique to, or at least much more pro-

nounced in, the present period. Although the mother in Now, Voyager was depicted as responsible for her daughter's illness, it was not presented as so inevitable as it appears in contemporary narratives. Nowadays the unhealthy dyad has expanded to encompass a seemingly endless trail of abusive mothers. Although Charlotte's mother was surely awful to the core, we never learn the reason for her nastiness, and it was definitely not referenced back to her own mother's behavior.

In contrast, even Joan's obsessive cleaning is portrayed as a response to her mother's uncleanliness. The desire to have a child is again seen as shaped by her own miserable childhood and the desire to "do it differently." As Joan says, "I'm going to give you all the things I never had." The echo of Mildred Pierce renders Joan's motivations for adopting a daughter immediately suspect: she wants to "give her everything," which we all know is not good for a child. Like Mildred, she is punished for wanting and desiring too much.

She is also punished for what can only be described as her narcissism. The daughter is made to be an object for the cameras at all times. This presents an interesting aspect of the male gaze question: Joan is placed as the person who offers up her girl-child as a spectacle for the publicity men, and the blame for this seems to be placed firmly on the head of the mother, who is, after all, herself a "victim" of the male gaze.

'night, Mother , made in 1986, deserves brief mention, although the poor quality of the film doesn't do justice to what was a significant and thoughtful stage play about mothers and daughters. Anne Bancroft chose to play the mother as a stupid and slightly hysterical "Southern white trash" woman. Sissy Spacek's anemic portrayal of a daughter who decides to take her own life never gets at the anger and venom directed at the mother in the stage version.

To a great extent, 'night, Mother is a film version of the "too much mother/not enough father" trope that pervades current discourses on mothers and daughters, feminist and nonfeminist alike. The specter of the dead father haunts this film: his picture is moved around the house, his gun is the one she uses, he is the subject of their fights, a specifically father-centered discussion is the catalyst for their battle throughout the film. In some ways, this film is about a "daddy's girl" whose one link to any depth and vitality was through her father. In one scene, in which the mother accuses her daughter of caring more for the father than for her, the daughter

Fig. 27.

Escaping the mother was never represented so literally as in 'night, Mother,

starring Sissy Spacek as a daughter driven to suicide as her mother helplessly

looks on. (Universal, 1986; photo courtesy of Museum of Modern Art

Film Stills Archive)

belittles her mother's allegation by claiming, "you were just jealous because I'd rather talk to him than wash the dishes with you." The mother's painfully honest reply ("I was jealous because you'd rather talk to him than anything") typifies her dilemma: she is the one faced with her daughter's suicide threats and daily life with her daughter (symbolized by the "washing dishes"); the father represents the escape from that life, from "reality" in a sense. Of course the mother is jealous. Who wouldn't be?

The climactic guilt scene follows, in which the mother pleads for her daughter to stop the talk of suicide and says the classic lines:

Mother: "It has to be something I did. . . . I don't know what I did, but I did it. I know. This is all my fault Jessie but I don't know what to do about it now."

Daughter: "It doesn't have anything to do with you."

Mother: "Everything you do has to do with me, Jessie. You can't do anything . . . wash your face or cut your finger."

The double bind is again vividly expressed here: the whole film leads us to believe that it is the mother's fault. Although the daughter explicitly opposes that interpretation ("It doesn't have anything to do with you"), she also implicitly supports it through her insistence on making her mother witness the nightmare of her own daughter's suicide: she is killing herself to escape her mother. The mother doesn't know what to do, how to reverse the "damage" she has unwittingly wrought on her daughter.

Woody Allen's 1987 Bergmanesque film September presents a very 1980s twist on the evil mother/victim daughter theme that is similar to both Mommie Dearest and earlier films such as Mildred Pierce . Allen has never been known to be a filmmaker sympathetic to the situations of women; quite the contrary, in fact. Indeed, women in Allen's films typically play the role of beautiful Gentile foils to his nebbishy neurotic Jewish prince. September is something of an exception to his usual setting because it moves out of urban Manhattan and into Allen's American equivalent of the Bergman petit bourgeois suburb. The entire film takes place over a weekend in the rambling Vermont country home of Lane (Mia Farrow). Lane's postbreakdown angst is complicated by the presence of her good friend Stephanie (Diane Wiest), who has come to stay for a bit, a young tenant and would-be writer Peter (Sam Waterston), with whom Lane has carried on an affair over the summer, an elderly neighbor (Denholm Elliott) who loves Lane, and Lane's visiting mother Diane (Elaine Strich) and stepfather (Jack Warden).

The central theme is the tension between mousy, insecure Lane and her vibrant, loud, egocentric mother, a former movie queen. The family secret, revealed in a climactic confrontation scene, is that when Lane was fourteen, she killed her mother's gangster lover (à la Lana Turner's daughter, Cheryl Crane). But the real secret, which we find out almost at the end of the film, is that mom actually pulled the trigger, and Lane was forced to take the rap for her.

The bossy mother's visit taxes the patience of an already flustered Lane, trying desperately to sell the house so she can move to New York and get on with her life (after a recent suicide attempt). The writer with whom she is in love is in love with Lane's friend Stephanie. Lane's mother thwarts her well-laid plans by announcing that she wants to keep the house, but Lane's anger (this is when the family secret is revealed) causes mother eventually to give in, leaving Lane the house at the end of the film.

The film is difficult to categorize because in many ways it represents a very modern perspective on mothers and daughters. This is mother-blame of a new strain, concerned not with simple neglect or with elementary overinvolvement, but with a sort of malicious narcissism born of a too independent mother and an overshadowed daughter. If this seems familiar, it might be because the ideologies of mother-blame have taken on a new edge in the age of the "working woman," the "latchkey child," and the "mommy track." Now mother is too sexual, too lively, too engaged with her own life. The plea of the daughter is now "Hey Mom, what about me? How dare you get on with your life? Getting on with your life has cost me mine!"

Numerous scenes throughout September establish Lane's exasperation with her mother and strongly hint at maternal responsibility for Lane's inability to move on with her life. In fact, Lane is quite explicit in blaming her mother (and her mother's active life) for her own stagnation; as Lane says to Peter about the shooting, "Yeah, she went on with her life. I got stuck with the nightmares." This is the heart of the double bind message: Mother is condemned for leaving the past behind, for not remaining forever guilty and miserable about the family tragedy, for living a happy life. She is a bad mother because she goes on and because her refusal of paralyzing guilt means the daughter cannot go on. Yet if she were to remain forever guilty, forever in penance, she would inevitably oppress the daughter with that guilt; she would pass it on to her as a legacy of pain to carry with her throughout her life. She cannot win.

Right from the beginning, we know that Lane is not at all pleased with her mother's presence in the country home. She enters the house a few minutes into the film, leans against the door, and says (with exasperation): "God, I can't believe my mother. She's out there, she's made friends with Peter and she's trying to get him to

write her biography. Her stupid life, as told to." So the sexual competition is set up right away: mother is taking her man away. Indeed, in a later scene with Lane and Peter, just about five minutes into the film, Peter is complaining about his frustration with his work, and Lane blames it on the time spent with her mother: "Well, if you wouldn't let my mother seduce you. . . ." Mother is thus both more sexual than daughter and more interesting, and this "problem" is referenced through the desired man: he finds mother more engaging than daughter. This exchange is immediately followed by Lane's devastating line ("Yeah, she went on with her life. I got stuck with the nightmares"), thus narratively linking the mother's seductiveness and vibrancy with the daughter's depression and suicide attempt.

In an early, revealing scene, the mother enters from outside with her husband and Peter, the writer. She comes in like a hurricane, graphically epitomizing the difference between her and the daughter, who has previously entered the house with slumped shoulders and an air of sad resignation. The choppy dialogue that follows perfectly sets up the mother as narcissistic and self-serving and the daughter as withdrawn victim of maternal egomania:

Mother: "Lane, I asked the Richmonds over for dinner tonight—I thought we could all have a little party."

Daughter: "What did you do that for? Peter and I were going to drive into town tonight. We were supposed to see the new Kurosawa film."

Mother: "Oh god, I'm sorry. Why didn't you say something?"

Daughter: "I did."

Peter: "That's OK Lane. We can catch it another night."

Daughter: "OK. But it's only there tonight."

Mother: "Where was I?"

As the mother talks to her, Lane is almost completely off-screen, deep in the background, almost telescoped at the end of the full images of the mother and her male attendees. When she utters the line, "Where was I?" the mother turns away from an already retreating, small Lane and, putting her arm around Peter, walks away. Thus the mother both physically and linguistically ignores the last line and recognizes only the resigned "OK." The daughter's reality, her wishes, are thus completely blotted out by the mother.

The pivotal scene occurs about ten minutes into the film. It is shot in the mother's bedroom, where she is getting ready for the little party with her husband. She says to him, "Lane's changed towards me. She used to get such a kick out of me." At that point, the daughter enters the room when mother and hubby are kissing; she hides behind the door during the entire scene and barely edges her way out. Mother takes up most of the screen and is often shot from below to make her appear even more formidable; the daughter seems small, afraid, and childlike compared to her mother. As they argue about Lane's refusal to move on with her life, the mother's breeziness is again made manifest, "If your life hasn't worked out, stop blaming me for it. It's up to you to take the bull by the horns." The scene shifts from touchy argument to bittersweet poignancy, with the mother gazing into her mirror, musing on her advanced years, and urging her daughter to "make something of herself" while she's still "got the chance." The scene ends with the return of the narcissistic mother as she switches abruptly from this expression of concern to a brisk attention to her evening attire.

Again, this scene reinforces the idea of mother as self-involved, domineering, unconcerned with daughter's problems, yet at the same time intrusive and judgmental, commenting with unmistaken glee on the daughter's failures in love ("The one thing you shouldn't do is let your desperation show. . . . I always felt there was a fatal element of hunger in your last affair."). She is sensitive only when it concerns her; then she moves blithely off to breezy trivialities.

This scene could be read a different way. One could understand the mother as powerful, refusing to take responsibility for the daughter's life but taking full responsibility for her own, concerned about the daughter and supportive of her romantic adventures, energetic and full of life, wanting her daughter to live fully, as she had, wanting to pass on her own youth to her. Strangely enough, upon first viewing, I read it completely "against the grain," contrary to the "preferred reading" offered up by the text. In that particular scene, I perceived Lane as insipid, whining, complaining: blaming her mother for whatever befell her. I completely identified with the mother's exasperation ("stop blaming me . . . get on with your life") and felt annoyed at Lane's continual attempts to squelch her mother's exuberance. Clearly, I read it this way at least in part from having done this research on mothers and daughters, for everyone I

questioned informally about this film, although not exactly thrilled with Lane's excessive whininess, nevertheless saw it as resulting from this narcissistic and overblown mother.

The only moment when the mother is portrayed sympathetically is qualified by her obvious drunkenness, rendering her apparent love for her daughter more than a little pathetic. She is sitting drunk over a Ouija board and talking to her dead husband, father of Lane: "Your daughter hates me. Our daughter hates me, and I love her. She's my one child and I want her to be happy. . . . I want her to forgive me." But even this sympathetic display could be seen as yet one more instance of her selfishness: she wants the daughter to forgive her so she can rest easier.

This film perfectly points out some of the double binds mothers and daughters are placed in. If a mother is too aggressive, too sexual (Lane is jealous that Peter is spending so much time with her mother), has her own life, and is self-determined and independent, she has denied her daughter the proper maternal care she needs to flourish; she is a bad mother who is selfish and narcissistic. (Mother here is endlessly talking about how she looks, how others look.) If she is self-sacrificing, solely domestic, and selfless, the daughter wants to escape from her, to leave that boring and depressing domestic/maternal world. If she does much for her daughter, is engaged and involved, she is intrusive, controlling, and "overinvolved." Many women blame their mothers for being boring, not engaged enough with the outside world, not "worldly" enough; yet if they are those things, they are neglectful and selfish mothers, capable of producing "maternal deprivation."

In this contemporary film where a mother is actually allowed to be sexual and alive, she is shown to be predatory, competitive with her daughter's lover, and, by extension, a neglectful parent. The daughter in this case is consequently desexualized, desensualized, and made out to be pathetic and a failure with men. No daughter ever wanted to grow up actually to be June Cleaver or the nearly anonymous mother in "Father Knows Best." Those domestic icons of the fifties are just that, icons, and almost never an image modern women actually strive to emulate. In this film, mother has dared to be "not just a mother," and daughter will inevitably suffer the results of her independence.

The most recent films on mothers and daughters do not bode

well for the future. The terribly miscast and woefully misbegotten remake of Stella Dallas (called simply Stella this time) starring Bette Midler as a swinging 1960s working-class barmaid (with a heart of gold and a truckload of working-girl integrity) only confirms the impossibility of the maternal sacrifice theme in an era of increasing (and increasingly sophisticated) mother-blame. Hewing very close to the original scenario, this Stella just can't tear at our heartstrings anymore. The narratives of sacrifice and class conflict have both been occluded by the onslaught of 1940s "momism," 1980s antifeminism, and the demise of popular representations of working-class life. Although the early Stella's martyrdom was so poignant in its exposure of the double binds of class and motherhood, this updated Stella is a retro narrative in search of a context, which no longer exists.

In Postcards from the Edge , Meryl Streep plays Suzanne Vale, the thinly disguised Carrie Fisher—author of the book and screenplay and daughter of Debbie Reynolds. An updated version of the bad Hollywood mother and her benighted daughter, the film traverses the terrain of September and Terms of Endearment all at once. Starting out as a bright and witty tell-all account of life in the Hollywood fast lane, it quickly slips into maternal melodrama overdrive. Once again, the brassy (but cracking inside) mother victimizes her hapless daughter, only to reunite in the requisite cataclysmic scene where mom's true vulnerability emerges, and daughter can now take care of the newly exposed mom.

Meryl Streep's Suzanne Vale is a young actor locked in a cycle of "B" movies and drug abuse. When an overdose lands her in a rehab hospital, the themes of maternal neglect and maternal narcissism (shades of September ) emerge. Mother misses the "family thing" at the hospital and instead breezes in late only to ignore her recovering daughter and play beloved movie star to a gay male couple who "do her" in their drag show.

This theme of maternal narcissism—of mother overshadowing the daughter and thereby "causing" her suicide attempt (September ) or drug overdose (Postcards from the Edge )—pervades this film. In a telling scene, mother has thrown daughter a welcome home party after her release from the hospital and forces her to sing for the crowd. Suzanne sings a melancholy song while mom mouths the words, coaching her from the sidelines as daughter stands in

front of a framed portrait of mom from her showgirl days. When mother Doris gets up to sing after requests from the assembled throngs, the contrast couldn't be more stark. The daughter's mournful, bluesy "You Don't Know Me" is replaced by mom's brassy, high-kicking showtune, "I'm Still Here." Even the cutaways are different: when mom watches daughter's performance, she is intrusive, anxious, and coaching; when daughter watches mom, she is obviously admiring, breaking into spontaneous shouts of energetic applause.

As in September , mom is sexually competitive with daughter. When a man comes to pick Suzanne up and Doris flirts with him, Suzanne says to her, "I would just like to have some people of my own is all, without them having to like you so much . . . why do you have to completely overshadow me?" Mom's response to Suzanne's attempts to challenge her "narcissism" are almost identical to those of the mother in September: "I think you should just get over what happened to you in your adolescence. It is time to move on ."

But daughter cannot move on until mom is shown to be the weak and vulnerable figure we know her to be. The cataclysmic scene begins with mom dumping vodka in her health shake after having informed her daughter that her agent has run off with all Suzanne's money. As Suzanne sits stricken on the stairs, Doris comes up to stand on the other side of the banister, informing her that "it's no good feeling sorry for yourself." When Suzanne says that she wants to get out of the business, her mother is only able to respond with yet another self-involved story:

Doris: "Let's take this one thing at a time. First, everyone is always getting out of the business and b: you are just like me. Somedays, I wake up and. . . ."

Suzanne (talking over her): "Will you please stop telling me how to run my life for a couple of minutes. Isn't it enough that you were right?"

As the battle heats up, mother directly addresses the question of blame ("You feel sorry for yourself half the time for having a monster of a mother like me"). Although daughter denies it ("I never said you were a monster!") and denies her mother's responsibility for her drug taking ("I took the drugs, nobody made me!"), the rest

Fig. 28.

Old movie queen Doris Mann (Shirley MacLaine) flirts shamelessly with

daughter Suzanne's (Meryl Streep) boyfriend (played by Dennis Quaid) in

Postcards from the Edge . (Columbia Pictures, 1990; photo courtesy of Photofest)

of the scene (as in September and 'night, Mother ) gives us ample evidence of mother's culpability:

Doris: "Go ahead and say it. You think I'm an alcoholic."

Suzanne: "OK. I think you're an alcoholic."

Doris: "Well, maybe I was an alcoholic when you were a teenager. But I had a nervous breakdown when my marriage failed and I lost all my money."

Suzanne: "That's when I started taking drugs."

So maternal culpability is clearly established here, or at least a causal relationship is set up between mother's drinking and daughter's drug abuse. But mother still resists:

Doris: "Well, I got over it! And now I just drink like an Irishperson. . . ."

Suzanne (talking over her): "Yeah, I know, you just drink to relax. You just enjoy your wine , I know, you've told me mother. You don't want me to be a singer. You're the singer. You're the performer. I can't possibly compete with you . What if somebody won? You want me to do well, just not better . . . than you."

Mother now stomps haughtily up the stairs past the daughter, turning around to look down at her from the top. As the camera looks up at her, from the daughter's angle, the imposing and threatening mother screams at the daughter that she can "handle it" (unlike the daughter) and then puts the question to her: "Will you please tell me what is the awful thing I did to you when you were a child?" Suzanne finally answers: "From the time I was nine years old you gave me sleeping pills!" As mom pathetically defends herself ("They were over-the-counter drugs, they were safe!"), she further implicates herself in a pattern of drug abuse and seductiveness toward the daughter's friends that clearly gives the lie to the daughter's earlier assertion of her own responsibility for her behavior. As the camera leaves the imposing maternal figure and moves alongside the daughter as she walks out the door, we hear off-camera (no longer the powerful image at the top of the stairs) the mother's desperate plea: "Don't blame me, I did it all out of love for you."

The next scene brings in the all-knowing father figure cum film director, played by Gene Hackman. He dispenses the wisdom of the women's magazines and popular psychologists discussed throughout this chapter: "Look, your mother did it to you and her mother did it to her and back and back and back all the way to Eve. At some point you just stop it and say fuck it: I start with me." Armed with that tidbit of fatherly insight, Suzanne can care for her (truly, deeply) vulnerable mom after she has a car accident while driving under the influence. As tender daughter applies makeup to the (denuded, unmasked, dewigged) mother, she is able to release her anger as mother is able to admit her jealousy. Both mother and daughter bounce back: mom goes out bravely to confront the press, and daughter closes the film with a music video production scene directed by the benign father figure previously seen granting solace and advice to a distraught daughter.

Another recent film, Mermaids , starring Cher and Winona Ryder as a mother and daughter locked in adolescent angst, helps construct a similar genre of "isn't mom wacky but really pathological underneath it all?" After getting over the initial stretch of imagining Cher as a Jewish mother, we are treated to a narrative that is much more effective as a coming of age drama than as a story about mothers and daughters. The adolescent alienation of mother from daughter is highlighted by the daughter's persistent reference to her as "Mrs. Flax" during her omniscient narration. Cher plays Rachel Flax, a rebellious refugee from a family of kosher bakers who traipses around the country with two young daughters in tow. The theme of movement is a crucial one because daughter Charlotte's rebellion is often signified by anger at her mother's easy mobility and refusal to stay "in place." The mother's constant movement, although momentarily amusing (as is her inability to feed her children anything but hors d'oeuvres: "Anything more," says her daughter, "is too big a commitment"), becomes understood quickly as signifying a more problematic refusal to grow up and a concomitant fear of responsibility. As Charlotte tells us again and again, mom moves on when the going gets tough.

This lighthearted yet melodramatic treatise on wacky moms comes complete with the Kennedy family as the recurring televisual reminder of the wholesome domesticity Charlotte yearns for. As the daughter retreats from mom's irreverence with fervent prayer, fantasies of eternal salvation, and desire for the never-seen absent father, she also begins to experience the sexual desires that seem to rule her mother's life and that will, inevitably, produce the final confrontation scene between mother and daughter. True to melodramatic form, an "event" occurs that brings mother and daughter to angry explosion and tearful reunion. Daughter's budding sexuality eventually provides the terrain for the reunion, which rings false precisely because it is based solely on the sharing of like bodies, not the sharing of values and beliefs.

The opening scene sets the stage, with teenage daughter Charlotte providing a wiser than her years voice-over detailing the nuances of her wacky family and particularly wacky and sexually active "Mrs. Flax." Mom's dereliction as a Kennedy-esque mother is treated with the humor that will eventually turn bittersweet and melodramatic (as in Terms of Endearment ):

Charlotte: "You never came to Parent-Teacher night before. I don't see what's so special about this one."

Mother: "Charlotte, you read the invitation: Community begins in the classroom. I am your mother, it is my job to watch over your education."

Charlotte: "There's so little of it left. What took you so long."

Mother: "Ohh, we're going to play my favorite game: who's the worst mother in the world? Oh now don't tell me, let me guess, who could it be? Could it be . . . ME?"

Although the scene is humorous and highlights the mother's awareness of "mother bashing" and refusal of guilt, the knowing humor is undercut by the mother's obvious "lack" in the realm of maternal commitment and responsibility. As funny as the hors d'oeuvres are, they are not what you feed two growing girls. As amusing as the premise of eternal mobility is, we know that it is disruptive to a developing child's sense of identity and continuity; it inspires terror in a child, not humor.

Even though other kids may envy Charlotte her rebellious mom, as we see in the comment a student makes to Charlotte at the PTA meeting ("See that woman there? That's my mom. And when I grow up I want to be just like yours"), we realize all too well that mom's obvious immaturity creates a daughter unable to revel in her own childhood. In one scene, the family has spent the night at the house of Lou Lansky, mom's shoe salesman boyfriend. When a storm wakes her up, Charlotte goes up to the attic, where mom has fallen asleep, having sat earlier for amateur painter Lou. As Charlotte kneels by the couch, she covers her mother up and gazes sadly on this woman dressed like a garish Cleopatra. Her melancholy voice-over utters the telling lines: "Sometimes I feel like you're the child, and I'm the grownup. I can't ever imagine being inside you. I can't imagine being anywhere you'd let me hang around for nine straight months." Again, while this bittersweet moment remains humorous, it also conveys the real sadness of a daughter who is both "parentified" and deeply unsure of her mother's love and concern.

As in so many films, the wise male savior points out to the mother the errors of her ways. In Mermaids , Lou repeatedly points out mother's failings and provides analysis and explanation for her bizarre behavior. When the family is at Lou's for dinner, the contrast between his rich and warm family meals and Rachel's haphaz-

ard domesticity (where the kids eat standing or sitting on countertops) could not be more pronounced. When Charlotte runs away to construct a fictional "Cleaver" family after a painful scene in which she is unable to talk to her mother about her fears of pregnancy, Lou is quick to lecture Rachel on her dangerously aggressive mothering style:

Mother: "You know, I know that she's doing this to turn my hair white."

Lou: "She's doing this because she has a problem! And she's probably too frightened to talk to you about it!"

Mother: "Why would she be frightened?"

Lou: "Rachel, you can be a little abrasive! Shit, even I'm scared to talk to you sometimes. She's a kid, lighten up, don't ride her too hard!"

Mother: "I don't need a lecture on parenting from you ! OK, that's it, when she comes, I'm leaving."

Lou: "And you wonder why she runs away from problems. Will you listen to yourself?"

When Charlotte returns, after being fetched by Lou, her mother is furious: "Go to your room. I can't talk to you right now. If I talk to you right now, I'll kill you." After attempts to talk with a resolutely silent Charlotte, who will only speak in cinematic voice-over, Rachel tries to reach her with this matter-of-fact statement of her own ambivalence: "Let me tell you something Charlotte. You know, sometimes being a mother really stinks. I don't always know what I'm doing. It's not like you and your sister came with a book of instructions. You know, if I can help you . . . just tell me. I'll give it my best shot, but I, that's all that I an do." When her daughter doesn't respond, the mother leaves the room.

The denouement occurs when Charlotte, convinced that her mother is trying to steal boyfriend Joe away from her, gets all dressed up and spends an evening getting drunk with her little sister: "OK mom, you want to drive Lou away, that's your business. You want Joe: that's war." As the sisters sit on the front porch, Charlotte's overly parental role in the family is made manifest, a role that will later come back to haunt her by the events that follow:

Katie: "Tell me about when I was born."

Charlotte: "Aren't you sick of hearing this story?"

Katie: "No."

Charlotte: "OK, you were born in a hospital on a cold winter's day, and when Mrs. Flax brought you home, I pretended you were mine."

Immediately following this scene, Charlotte and Katie go to the convent where Joe (the boyfriend/caretaker) lives. As he and Charlotte make furtive love in the belltower, her inebriated little sister falls into the stream and is saved in the nick of time by the nuns. This event serves as the catalyst for Charlotte's confrontation with her mother. As the furious mother returns from the hospital, the penitent but awakened Charlotte refuses her usual silence in favor of "having it out" with mother:[30]

Mother: "If you're smart you'll just stay away from me."

Charlotte: "Don't walk away from me, mom, you're not going to walk away from me! I am not invisible! Talk to me! Now! Yes, I made a mistake. Yes, I am really, really sorry. It was a big mistake. I know that. You make mistakes. You're always screwing up and we're always paying for it. Everytime you get dumped, everytime you dump on somebody. And it's just, it's not fair mommy, it's not fair."

Mother: "I am sick and tired of being judged by you. You're a kid. OK, when you become an adult you can live your life anyway you want to. But until then, we'll live my life my way. Start packing."

Charlotte: "No!"

Mother: "I said pack. This move is on you and if loverboy doesn't like it, that's too goddamn bad."

Charlotte: "This is not about him, this is about me, OK? That's over, he is gone, he has left. . . ."

Mother: "Surprise, surprise. . . ."

Charlotte: "No, it's not like that. Look, maybe your life works for you but it doesn't work for me. And I want to stay."

Mother: "And do what?"

Charlotte: "Finish high school."

Mother: "Great start, what's your major? Town tramp?"

Charlotte: "No, Mom. The town already has one."

They do, of course, end up staying, after mother and daughter have bonded over their relationships with men:

Mother: "You know, you're just one year younger than I was when I had you. If you hate my life so much, why are you doing your damnedest to make the same mistakes? . . . How do you feel about this guy?"

Charlotte: "I thought I loved him."

Mother: "Sounds familiar."

The reunion ends with a teary daughter questioning mother on her relationship with the absent father ("Did you love my father?"), and an epilogue follows that maintains mother's bantering relationship with Lou without completely altering her persona of "wacky mom."

Both Postcards and Mermaids thus replicate the mode seen in films of the fifties, where mother is not wholly killed off but rather "fixed" within the confines of the nuclear family, as it internally cleanses itself of its own deviations. In keeping with the madcap generic conventions, mom is "fixed" while still retaining her wackiness and idiosyncratic style. Daughter's point has been made: mom is now forced to face up to her responsibilities and finds with the daughter a new intimacy based on a recognition of their mutual enmeshment in the world of (male-defined) sexuality.

These 1980s paradigms have been challenged here and there by the lone book, film, or TV show. A number of books and articles shift significantly away from the simple themes of "loving and letting go," although they are few and far between and generally don't have the same popular appeal as, say, a piece by Colette Dowling. Terri Apter's Altered Loves argues explicitly against the ideologies of separation and for a more nuanced and complex understanding of the changing affiliations daughters and mothers negotiate. Apter strongly urges us to distinguish different meanings of "separation":

First, there is separation as individuation—the development of a distinct self, a sense of self-boundary, enabling one to distinguish one's own wishes, hopes, and needs from those of one's parents. . . . The second sense of separation is like a divorce. It is breaking the bonds of affection with the parent. . . . We must distinguish between individuation as self-identity, and some sense of self-determination or self-agency, and between individuation as a means of separating from others, cutting bonds of affection.[31]

Apter's interviews with sixty-five British and American mother/daughter pairs reveal not the "truth" of inherent separation and

struggle, but rather the much more complex negotiation of new patterns of closeness built out of a sense of reciprocal effect and care. Apter eloquently critiques both mainstream and feminist theories for their commitment to the "myth of separation" and their endless perpetuation of mother-blame.

Emily Hancock's The Girl Within: Recapture the Childhood Self, the Key to Female Identity , although unfortunately mired in the contemporary obsession with "the child within," nevertheless manages to critique soundly the ideology of separation that is revealed to be more problematic when put to the test of actual interviews: "They did not want to break the mother-daughter bond; they wanted to transform it. Given the cultural ethos that urges separation on adults, the burden fell on each individual daughter to rework the attachment without forfeiting it. In a culture hellbent on separation, this activity took on an almost subversive character."[32]

Paula Caplan challenges mother-blame head on in her passionate treatise, Don't Blame Mother , where she urges us to critique both the myth of the "perfect mother" (who must inevitably fail us) and the myth of the "evil mother" (who must also fail us): "Mothers are either idealized or blamed for everything that goes wrong. Both mother and daughter learn to think of women in general, and mothers in particular, as angels or witches or some of each. . . . As daughters and mothers, we have for generations been trapped in a dark web we did not spin. But once we are aware of the myth-threads that form the web, as we tell our mothers' stories and our own, we can begin to sort them out and pick apart the web."[33]

These texts, all using extensive interview material and all written by psychologists, struggle to forge a new conceptualization of mothers and daughters that avoids the dominant patterns of dichotomizing mother-blame while remaining critical of the feminist tendency to replicate these selfsame patterns. However, all three texts remain within a solidly psychological framework and place their revisions within an interpersonal, rather than a more broadly social, context. Although many of these writers point to a culture of mother-blame and woman hate as the culprits in creating a climate of expected hostility between mother and daughter, they often leave these insights as mere asides to the more central topic of psychic reconstruction. Nevertheless, the presence of these alter-

native frameworks can only help in the project of reimagining the mother/daughter relationship.

The backlash of the eighties and early nineties has thus added a sad twist to the question: Whose life is it, anyway? As all women's lives (daughters and mothers) become more and more out of their own control, popular culture still insists on making this question of social control subordinate to the putative timelessness of maternal control and domination. For Adrienne Popper of Parents' Magazine , the question is addressed from daughter to mother: "The division between mothers and daughters here, as always, is one of control, a question of 'whose life is it anyway?' Undoubtedly, daughters can derive enormous benefits from mothers who allow them to live their own lives with maximal maternal support and minimal interference."[34] This question needs rather to be addressed by all women (daughters and mothers) to the institutions and persons of male power and authority. The difference is not simply one of enunciation (who speaks what question to whom); it is instead a radically political difference: the difference between turning inward to locate oppression or turning outward to challenge it.