Parallel Directions

Despite their unusual character, the illustrations in A and C are not the first examples of visual allusions to Aristotle's concepts of Justice. Earlier trecento fresco programs have been associated with the influence in Italy of native thinkers trained in France to apply Aristotelian ethical and political concepts to the structures of the Italian city-state.[57] For example, recent scholarship has postulated various Aristotelian contexts for Giotto's famous figures of Justice and Injustice in the Arena Chapel in Padua. Consecrated in 1305, the structure reflects an elaborate drama of Christian salvation. References to the foundation of the state on principles of law and justice are expressed in the central position of Justice on the lowest zone of the wall (Fig. 30). More specifically Aristotelian are the subtypes of Distributive and Remedial Justice. Although not identified verbally, they are depicted by groups of classically inspired figures placed on the pans of the scales held by Justice.

Figure 30

Giotto , Justice. Padua, Arena Chapel .

Figure 31

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Justice.

On the left, a small winged form acting as Distributive Justice bestows a reward on a (now headless) figure seated at a desk.[58] An implicit reference to Remedial Justice occurs on the right, in the pan held by the virtue's left hand. There, a Jupiter-like figure cuts off the head of a man placed on the arm of Justice's throne.

The major theme of Ambrogio Lorenzetti's fresco cycle of Good and Bad Government, decorating the Sala dei Nove of the Palazzo Pubblico, Siena (dating from 1337 to 1340), is the association of Peace and Justice with Good Government (Fig. 31). Until recently art historians generally accepted the assertions in Nicolai Rubenstein's classic article of the connection of the Sala dei Nove program with Aristotelian and Thomistic concepts.[59] Quentin Skinner opposes these Aristotelian links by stressing the ideological connections of Lorenzetti's frescoes with thirteenth-century Italian prehumanist rhetorical writers on city and republican government.[60] After a lengthy analysis of the iconography, including the choice and distribution of the virtues and vices, Skinner singles out as the most important source of Lorenzetti's program Brunetto Latini's encyclopedia of 1263, Li livres dou trésor . Although Latini's work was based on the paraphrase of the Nicomachean Ethics by Hermannus Alemannus and not on the Grosseteste translation, Skinner emphasizes the differences between Aristotelian concepts of the virtues and vices, and

Latini's.[61] Instead, Skinner stresses the Ciceronian and Latin character of Latini's moral thought and its direct reflection in Lorenzettian iconography.[62] Although more reluctant to limit the texts chosen by the artist or a learned adviser, Randolph Starn also favors Latini's work as an analogue to the frescoes in their use of the vernacular, encyclopedic structure and extended discussion of the virtues and vices.[63] Chiara Frugoni, who underscores the importance of biblical and other religious writings, also hesitates to limit the textual sources of the Lorenzetti frescoes. Like Starn, she emphasizes the importance of the vernacular inscriptions.[64]

Although scholars disagree on the iconographic sources of the Palazzo Pubblico program, they stress the fundamental importance of Justice in the elaborate central allegory and its extensive inscriptions. Justice is a young, crowned, and richly clad figure who is seated frontally (Fig. 31). The figure of Sapientia (Wisdom), issuing from a divine realm, floats above her head. Directly below Justice, linked by a cord, Concordia relates her to the central figure variously identified as Good Government, the ideal public authority of Siena, or the Common Good (Fig. 53). Inscriptions identify smaller winged figures on either side of Justice. Hovering on the left of the throne, Distributive Justice crowns a kneeling figure, while she prepares to behead another person with arms bound behind him. On the right, level with the main figure's left hand, Remedial Justice gives weapons to one man and reaches into a box, probably to reward another.[65] In Lorenzetti's program, the large female figure corresponds to Legal or Universal Justice. In turn, the central and biggest figure, the masculine ruling authority, is flanked by an expanded series of cardinal virtues, including another depiction of Justice.[66] This one holds a sword in her right hand and a crown in her left. A severed head resting on her lap implies that she has the power to reward the just and to punish the unjust ruler.[67]

Thus, in trecento Italy the Giotto and Lorenzetti allegories establish a political context for the representation of Justice with Italian/Latin prehumanist and/or Aristotelian roots. In a broad sense, certain similarities link Figures 24 and 29 to those of the Paduan and Sienese cycles. Also, the ordering of the four images shares common features. All conform to practices suggested in scholastic memory treatises. Embodied in human, idealized forms, clothed in striking dress, and identified by inscriptions, the ethical concepts associated with the virtues are placed in a specific architectural context located within a larger scheme. Their size reflects their importance in regard to subtypes of related personifications.[68] Particularly relevant is the concept of Legal Justice, a supernaturally large form embracing in a similar sequence the subtypes of Distributive and Remedial Justice.

Despite these general resemblances, the images in A and C have a distinctive French character. The political context and place of operation of Figures 24 and 29 are associated with the kingdom of France, identified by the prominent fleur-de-lis motif. Also different from the Giotto and Lorenzetti allegories are the specific ordering principles adopted in the images of A and C . The concept of Justice légale as a universal or embracing principle is more fully developed by means of the mantle motif and the inclusion of the daughter virtues. Moreover, in the miniatures of A and C , Justice légale is a sovereign ruler herself, dominant in the highest sphere. Unlike the Giotto figure in the Arena Chapel program, she is

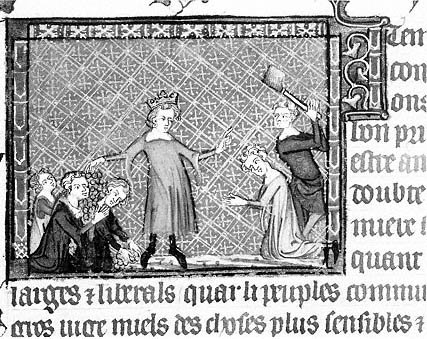

Figure 32

A King Acting as Distributive and Remedial Justice. Avis au roys.

not the foundation of a divine scheme unfolding above her in the main pictorial space. Nor, as in the Lorenzetti program, is Justice légale subordinate in scale to a ruler, or dependent on a superior force, Divine Wisdom. Instead, Justice légale is literally the uppermost ruler: in her own right she embodies a spiritual power independent of any overt Christian agent.

The ordering of the lower register of Figures 24 and 29 shows even greater differences from the Giotto and Lorenzetti images. Although subordinate to and subtypes of Justice légale, Justice distributive and Justice commutative enjoy greater status than their Italian counterparts. The sister Justices form centers of activity independent of the figure above. Unlike the Giotto pair, the twin Justices are both female. Whereas the Lorenzetti duo also expresses the notion of twinship, gender is less important than divine origin. In contrast, the sister Justices of A and C are clearly rooted in the earthly sphere, and those of A further assume an expressive, fully human identity. As concrete examples of the workings of Distributive and Remedial Justice, the miniatures of A and C more accurately define the Aristotelian concepts than the Italian works.

Most important, the Morgan Avis au roys (Figs. 25 and 26) provides abundant models for the iconography of Justice légale. This manuscript also introduces the concepts and adjectives describing the distinctive functions that characterize the twin Justices of the lower register.[69] An image from the Avis au roys embodies the operations of Justice distributive and Justice commutative. Figure 32 depicts a

king giving coins to a group at the left, while on the right he instructs an executioner to behead a subject. Here the workings of the Aristotelian subtypes of Justice are identified with the actions of a ruler represented in other miniatures of the cycle as a king of France. Indeed, the prominent representations of Justice in the program of MS A may ultimately derive from the mythic association of this virtue with the people and rulers of France.