Altered Rangelands

Cattle and Sheep, Great Basin of Western North America

(Burkhardt and Tisdale 1976; Christensen and Johnson 1964; Lanner 1981; Mack 1984; Madany and West 1983; Robertson 1971; Rogers 1982; Vale 1974, 1975; West 1983; Yensen 1981; Young and Budy 1979; Young et al. 1972, 1976)

The high, arid intermountain region of western North America has cold, snowy winters and hot, dry summers. Under original pristine conditions, salt flats in the valley floors, where they were not completely barren, had scattered greasewood, Sarcobatus vermiculatus , and other chenopod shrubs. Vast areas on lower slopes around the basins were dominated by less extremely halophytic chenopod shrubs, for example, shadscale, Atriplex confertifolia ; wing-scale, A. canescens ; and winterfat, Ceratoides lanata . At slightly higher levels, big sagebrush, Artemisia tridentata , dominated tens of millions of hectares; it was commonly accompanied by rubber rabbitbrush, Chrysothamnus nauseosus , and other shrubs. At still higher elevations, big sagebush was joined by junipers, and still higher, by pinyons. Juniperus osteosperma and Pinus monophylla were the most widespread of these scrub conifers. Above the scrub conifer woodland in the highest mountains were forests of tall conifers.

The region also had native grasses. Meadows along streams carrying snowmelt from the mountains had a tall perennial wild rye, Elymus cinereus . Among the scattered sagebrush and the scrub conifers grew sparse perennial grasses, such as Agropyron spicatum, Poa secunda, Sitanion spp., and Stipa spp. The grasses aestivated during summer and the dried grass sometimes burned. Most grasses were not killed by fire, but sagebrush, junipers, and pinyons were. Fires did not generally spread far before being stopped by lack of fuel, especially on steep slopes and rocky ridges. Thus, burns created a patchwork of different-aged stands of sagebrush and woodland.

The vegetation was probably originally in near equilibrium with the native herbivores. Bison were few, in contrast to the great herds east of the Rockies. Other ruminants—mule deer, pronghorn antelope, and bighorn sheep—were present in limited numbers. Their facultative browsing and

grazing put little pressure on the vegetation. Rabbits and rodents were generally more important plant consumers.

The Indian inhabitants of the region were hunters and gatherers. They harvested plentiful crops of wild rye and pinyon nuts. There is no evidence that they had a significant effect on the vegetation.

Mormon settlements, starting at Great Salt Lake in 1847, rapidly fanned out through the region seeking irrigable land for intensive subsistence farming. Mormon livestock culture initially followed the North European pattern: community milk and meat cattle, draft animals, and sheep were kept in the settlement at night and herded nearby during the day. The result was severe but very localized overgrazing.

Extensive commercial livestock production developed in the Great Basin from different roots, that is, the Spanish American pattern of open range without fences or stored feed. It was stimulated by the mining booms and demand for meat in California after 1849, in Nevada's Comstock Lode after 1859, and by subsequent mining strikes. The areas of old Spanish settlement in California and New Mexico provided a source of cheap, abundant cattle and sheep to found the Great Basin herds. The range was free and belonged to those who got there first. Except during annual roundups, cattle and reserve horses were essentially free-ranging feral animals. Sheep were herded in large flocks, initially often without a home ranch. Itinerant sheepherders claimed as much right to free grass as anyone and drove their flocks wherever the grazing was best.

Initially, there was enough grass so that livestock could survive normal winters on the open range without unacceptable losses. However, overstocking and recurring droughts during the 1870s and 1880s greatly depleted the grass. In the severe winter of 1889–1890, over 250,000 head of livestock died on the ranges of northern Nevada alone. A new pattern then developed based on home ranches on streams with meadows supplying hay for winter feed for cattle and some sheep. Ranchers who had homesteaded the valley meadows inherited use of the surrounding open rangelands, theoretically federal property. The natural meadows were expanded by irrigation. The Indians commonly became hired hands on the ranches. Instead of harvesting wild rye and pinyon nuts, they fed hay from their ancestral meadows to cattle and cut pinyon and juniper trees for ranch firewood and fence posts. Some itinerant sheep operations still owned no home ranches and wintered the flocks in the lower elevation shadscale deserts.

In spite of occasional setbacks, livestock numbers continued to build up until early in the present century. Between 1900 and 1920, Nevada had an average of over 1,200,000 sheep, 400,000 cattle, and 70,000 horses. Feral horses kept grazing pressure on open ranges in winter, when ranches were feeding cattle at home. Since then, cattle numbers have fluctuated around the same level, while sheep and horse numbers have dropped precipitously to about 200,000 and 20,000, respectively. Droughts and depression in the

early 1930s wiped out most of the large sheep operations. Finally, in 1934 Congress passed the Taylor Grazing Act, under which 70 million ha of federal land in the western United States, including 71% of Nevada, were withdrawn from unrestricted open range and organized into controlled grazing districts. By then much of it had been reduced to nearly pure stands of unpalatable brush. Much of it was so degraded that even where grazing had been completely excluded for over 30 years, little recovery of forage production has taken place. It took less than 90 years for ranching and sheepherding to irreversibly alter the region's plant geography by unintentionally caused local and long-range plant migrations.

The most catastrophic retreats have been by native grasses, while the greatest advances have been by exotic grasses and weedy dicots. The wild rye, Elymus cinereus , in meadows along streams did not survive well under either grazing or mowing for hay and has been largely replaced by irrigated alfalfa, Medicago sativa , and Kentucky bluegrass, Poa pratensis , both natives of Eurasia. On the open range, whatever grasses are now present are predominantly Eurasian annuals with a long history of survival under intense grazing. The most abundant of these is cheatgrass or downy brome, Bromus tectorum ; it was first observed in the region about 1900 in western Nevada. The seed evidently was brought in the coats of sheep driven from California, where cheat had arrived a few years earlier. Unpalatable when mature, cheat has spread to fill the vacuum left on millions of hectares by removal of the native perennial grasses. This substitution appears to be permanent. Even in stands where remnants of the native grasses survive and livestock have been excluded for over 50 years, the natives do not displace cheatgrass. Another unpalatable Eurasian annual grass, Medusahead, Elymus caput-medusae , was also apparently brought from the Pacific coast in the coats of sheep. Arriving in the Great Basin in the 1930s, it spread rapidly in heavier soils than cheatgrass. It is still spreading in overgrazed areas, but in some areas where grazing has ceased, it has been replaced by a native perennial grass, Sitanion .

Various Eurasian annual dicots have also invaded the region. As noted above in Chapter 4, Salsola spread throughout the western states as a railroad ruderal. Accompanied by another Eurasian tumbleweed, Sisymbrium altissimum, Salsola fanned out into rangelands. Salsola obviously benefits from soil disturbance and removal of competition by grazing. A related chenopod, Halogeton glomeratus , was an obscure wild species in deserts east of the Caspian Sea until it showed up as a ruderal near Wells, Nevada, in 1934. It had spread widely along roads and in rangelands before it was recognized as toxic to sheep; it has killed thousands of sheep in the Great Basin. Halogeton now grows on millions of hectares of overgrazed Atriplex confertifolia and Artemisia tridentata rangeland. Halogeton leaf litter enriches the soil surface with salt, which favors its own seedlings over competitors.

Some of the palatable native shrubs have stories parallel to the native grasses. Formerly abundant species of Atriplex and Ceratoides that once supported

ported many sheep are now gone from large areas. Other native shrubs have had more complex changes in distributions, as have pinyon and juniper. They have been buffeted by changes in the fire regime more than by direct effects of browsing. When domestic livestock were first brought into the region, fire frequency may have been increased deliberately, especially by sheepherders, to stimulate grass; the woody vegetation may then have lost ground. Also, the Comstock Lode and later mining operations within the region consumed vast quantities of pinyon and juniper wood for mine timbers, fuel to power machinery, and charcoal for smelting. By the time mining collapsed late in the nineteenth century, trees had been stripped from country around mining centers up to an 80-km radius. How much effect this exploitation had on pinyon and juniper geography is uncertain; seedlings and saplings must have survived.

Meanwhile, as grass was lost from overstocked rangelands, fire could no longer spread. Unrestricted by fire and unbrowsed, big sagebrush spread where more palatable shrubs had been removed. So did junipers, pinyons, and other conifers where they were not being cut.

With the arrival of cheatgrass, the situation in the area it invaded was again reversed. The ungrazed mature grass was commonly dense enough to carry fires that killed patches of sagebrush, pinyon, and juniper. Also, after World War II, extensive areas of sagebrush and pinyon—juniper woodland were killed with herbicides or crushed and uprooted with heavy equipment to destroy the woody vegetation in an effort to increase grass production. Between 1960 and 1972, about 150,000 ha of woodland in Nevada and Utah were destroyed with heavy chains dragged between tractors by the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management. There was no hope of bringing back the native grasses, so the chained areas were generally seeded with Eurasian perennial grasses. Management of federal lands in the Great Basin has become very sensitive politically, with cattlemen and environmentalists in polar positions on continuation of grazing. The cattlemen have a great asset in the popular view of cattle grazing as part of the romantic western tradition. Few people except range scientists are aware of the impact of grazing on the Old West.

Feral Livestock, California Channel Islands

(Brumbaugh 1980; Coblentz 1978; Dunkle 1950; Goeden and Ricker 1981; Goeden et al. 1967; Hobbs 1980; Johnson 1980; Minnich 1980, 1982; Philbrick 1972, 1980; Raven 1963; Thorne 1969; Westman 1983)

After the prehistoric extinction of pygmy mammoths, the vegetation of the islands off the southern California coast was untouched by large herbivores before the introduction of livestock in the nineteenth century. The only

terrestrial mammals were rodents, skunks, and diminutive foxes, all of which may have ridden in the seagoing canoes of the Chumash Indians who frequented the islands. The islands were never connected with the mainland, but during glacial low sea stands, the channel separating some of them from the mainland was only a few kilometers wide and presumably easily swum by the elephants.

The rich native flora included many endemic species, some of which are believed to have originated on the islands by adaptive radiation. Others are survivors of once widespread species known only as fossils on the mainland, such as island ironwood, Lyonothamnus floribundus , and island oak, Quercus tomentella . Many of the native island species are conspecific with those on the nearby mainland, although it has been suggested that shared chaparral shrubs evolved more arborescent forms on the islands. This so-called island gigantism may be an artifact of grazing and browsing by feral sheep and goats. Their voracious consumption of plant material reduced fuel and prevented chaparral burning, which was probably always less frequent than on the mainland because of the maritime climate. The chaparral shrubs thus have prolonged lives while being trimmed up to tree form by browsing.

Each of the eight major islands has had a different history of livestock introduction. Four will be sketched here.

San Miguel is the westernmost and most windswept of the islands. It is rather low and most of its 37-km2 surface is covered with Pleistocene dunes. In Holocene time, these had been stabilized by a cover of coastal sage scrub and grass. In the mid-nineteenth century, the island was stocked with over 6,000 sheep and some cattle and horses. During 3 years of drought in the 1860s, nearly all of these starved to death. Overstocking continued, and during subsequent droughts over half of the island became a waste of drifting sand. Regrowth during wet years was mainly by grass and other herbs. The number of sheep was finally reduced to about 3,000 in the 1930s and most were removed in 1950. After the National Park Service took over the island, the remaining sheep were shot in 1968 and feral burros were removed in the 1970s. Successive aerial photographs show gradual revegetation of some of the dunes since 1960. However, the original coastal sage scrub and grass vegetation has not recovered. Some recolonization is by a native morning glory vine, Calystegia macrostegia , found on coastal bluffs on the islands and mainland. Much of the colonization is by the perennial Australian ice plant, Mesembryanthemum aequilaterum , discussed in Chapter 1.

Santa Cruz is the largest and most rugged of the islands, with an area of 250 km2 and peaks up to 750 m high. Cattle, horses, sheep, and pigs were introduced in the mid-nineteenth century. Cattle and horses have remained under control, mainly in valley grasslands and on gentle slopes. Vegetational changes there are much like those that began earlier in mainland grasslands. The native perennial bunchgrasses have declined under grazing and have been mostly replaced by annuals. Some of the annuals are unpalatable natives,

such as doveweed or turkey mullein, Eremocarpus setigerus , probably originally confined to intermittent watercourses, and a tarweed, Hemizonia fasciculata , which may have been a member of the original grassland. The cattle and horse pastures are now dominated by European annuals, among the most common being a wild oat, Avena barbata ; brome grasses, such as Bromus mollis, B. rubens , and B. diandrus ; filaree, Erodium cicutarium ; burr clover, Medicago polymorpha ; cat's ear, Hypochaeris glabra ; and milk thistle, Silybum marianum . The pastures have also been heavily invaded by a European perennial, Foeniculum vulgare (fennel), which was introduced to California as a culinary herb and has spread widely as a ruderal. On Santa Cruz Island, it dominates pastures near the boat harbor and ranch house. Although eaten by cattle when young, it is evidently unpalatable when flowering. It is currently spreading rapidly, not only in pastures but under scrub oak woodland that appears undisturbed. As on the mainland, cattle have had relatively little impact on the native scrub and woodland vegetation.

Sheep have had far more impact on Santa Cruz Island scrub, both coastal sage and chaparral, and on woodland, both hardwood and pine. By 1870, the island had about 45,000 sheep and by 1875, about 60,000. They were allowed to run free and only about half could be rounded up for shearing annually. Tens of thousands were slaughtered during drought years to prevent total desertification and starvation. Feral pigs also became abundant during the late nineteenth century and prevented reproduction of both scrub oaks and woodland oak trees by rooting for acorns. Late nineteenth century accounts and photographs record progressive destruction of coastal sage and other vegetation and increasing erosion. In the bare areas, a cactus native to coastal bluffs, Opuntia littoralis s.l., spread inland. Most of the denudation took place during the late nineteenth century. Since aerial photographic coverage began in 1929, there has been little further attribution of woody vegetation except near the eastern tip of the island, which continues to be operated as a sheep ranch.

Starting in 1939, the Stanton Ranch, which had acquired all but the eastern tip of the island, began trying to eliminate the sheep. Tens of thousands were shipped to market and tens of thousands of others that could not be caught were shot, along with innumerable pigs. During the 1950s, the Stanton Ranch built a huge network of fences to control the cattle and exclude sheep and pigs from large portions of the island. The fences are often broken through by pigs and by floods in stream channels, so the feral sheep and pigs are seldom completely absent for long. However, the vegetation contrast across some fence lines is dramatic. In wet years, the contrast is less striking because of temporary cover by European annuals in the sheep country. Generally the sheep side of the fence has much more bare ground, browsed shrubs, and no young trees.

Since the 1929 photographs were taken, a stand of bishop pine, Pinus muricata , in sheep country on the north side of the island has decreased

greatly in density. The trees are all 40 to 70 years old with no seedlings or saplings; the average life span of a bishop pine is about 65 years. Two other bishop pine stands on the island had no seedlings and also faced extinction before sheep were fenced out in the 1950s. Pine reproduction is now abundant in various age classes. Reproduction of other native trees and shrubs is virtually nil in sheep country, with a few exceptions, including an unpalatable bush groundsel, Senecio douglasii .

The Nature Conservancy is in the process of taking over the Stanton Ranch and faces the formidable task of eliminating feral livestock. It is probably already too late to save some species, for example, an endemic monkey flower, Mimulus brandegei , first seen in 1888 and last seen in 1932.

The invasion of the interior of Santa Cruz Island by the coastal Opuntia littoralis has been reversed by a biological control program, the oldest one in North America and the only one anywhere to successfully control a native weed with purposely introduced insects. In 1939, an estimated 40% of the rangeland was considered useless because of dense Opuntia infestations. In 1940, entomologists from the University of California, Riverside, and the Stanton Ranch began working to establish insects that fed on Opuntia littoralis on the mainland coast but that were not present on the island. The most successful was a cochineal bug, Dactylopius opuntiae , which since 1951 has destroyed most of the Opuntia populations of the island. At present the situation appears to be equilibrating, partly because the cacti are less dense and more resistant kinds have survived, but mainly because the cochineal bug was followed to the island by some of its own predators, particularly a moth, Laetilia coccidivora , which arrived in the early 1970s. Areas of dead cactus have commonly been recolonized by native coyote brush, Baccharis pilularis .

Santa Barbara Island has a surface area of only 2.5 km2 , mostly on a low mesa that emerged from the sea in Pleistocene time. In spite of its recent origin, the island has a native flora of about 70 species, all but one shared with other islands or the mainland; a species of live-forever, Dudleya traskiae , is endemic to the island. Vegetation on the mesa top was largely destroyed by cultivation of crops, a topic outside the scope of this chapter. However, the peripheral bluffs and sea cliffs are relevant here because they were invaded by feral livestock in the form of domesticated European rabbits. These were introduced by military personnel stationed on the island during World War II, after the island had been declared a national monument and farming was excluded. The rabbit population peaked at about 2,600 in 1955, destroying most of the native coastal bluff vegetation, which had been dominated by the arborescent sea dahlia, Coreopsis gigantea , and a morning glory vine, Calystegia macrostegia . An annual South African ice plant, Mesembryanthemum crystallinum , took over much of the denuded area. The National Park Service began shooting rabbits in 1954, and by 1958 so few rabbits were left that the native species began to regenerate from sprouts and seedlings. Even the endemic Dudleya traskiae , which had been considered extinct, reappeared in 1974 in former rabbit territory.

Santa Catalina is almost as large and rugged as Santa Cruz and has similar natural vegetation, except that Catalina has no pine forests. Feral goats were probably present by 1840. The island had commercial sheep and cattle ranching from about 1850 to 1950, when domestic livestock other than some bison were removed. Late nineteenth-century photographs of Catalina show that overgrazing was already widespread and severe: coastal sage scrub was nearly gone, chaparral had been opened up to a scrub savannah, and the coastal Opuntia littoralis had invaded bare inland areas. Pigs were introduced in the 1930s. Today feral goats and pigs are abundant on much of the island. Goat browsing has selectively eliminated most chaparral and coastal sage species, leaving unpalatable Salvia apiana, S. mellifera, Rhus integrifolia , and R. laurina . In the worst goat-occupied wastelands, the only perennials are Opuntia littoralis s.l. and the South American Nicotiana glauca . The Catalina Island Company chose not to introduce cactus-feeding insects, preferring cactus cover to bare ground.

Development of the resort town of Avalon in the 1890s was followed by dramatic reinvasion of surrounding parts of Catalina by native shrubs. Slopes within sight of the town are shunned by the goats. What was in the 1880s an overgrazed landscape of sparse grass, cactus, and scattered browsed shrubs had by 1900 become covered by coastal sage scrub. Since 1940 the area has been invaded by chaparral species, notably the bird-dispersed Rhus integrifolia and Heteromeles arbutifolia . The same two species are invading stands of Quercus dumosa in goat-free areas where pig rooting has completely stifled oak reproduction. The Island Company has carried out goat removal and fencing in parts of the islands. This work may be expanded because most of Catalina has been placed in a conservation easement with the Los Angeles County Department of Parks and Recreation. In areas where the goats are gone, native shrubs are recolonizing rapidly. One of the most successful of these is the endemic St. Catherine's lace, Eriogonum giganteum . Of about 200 species in the original native flora, about 40 have not been seen in the last 25 to 30 years. Some of these survive on neighboring goat-free islets. Others are shared with other major Channel Islands or the mainland and may return to Catalina some day. Others are believed extinct, such as Mimulus traskiae , known only from Catalina and not seen for 50 years.

Rabbits, Lisianski Island, Hawaii

(Clapp and Wirtz 1975)

Lisianski is a low, coral sand island, about 200 ha in area, located about 1600 km northwest of Oahu. In the early nineteenth century, it was described as having a few patches of coarse grass and shrubs (the species not named), abundant elephant seals and green turtles, and teeming seabird rookeries. Between 1904 and 1909, the island was occupied several times by Japanese

landing parties, who killed several hundred thousand seabirds for sale of feathers to the French millinery trade. In 1909, Theodore Roosevelt declared the island a bird sanctuary. When the Japanese left, they did not take their domestic rabbits. By 1914, the rabbits had eaten all the vegetation on the island except for some tobacco plants near the abandoned houses and two vines of an Ipomoea sp., perhaps I. pes-caprae , the pantropical beach morning glory; most of the rabbits had starved to death. By 1916, all the rabbits were dead and there were no traces of plant life except some algae.

A scientific expedition in 1923 found four plant species on Lisianski: Eragrostis variabilis and Nama sandwicensis , which are Hawaiian Island endemics that are probably bird dispersed, and Portulaca lutea and Sesuvium portulacatrum , which are pantropical, sea-dispersed beach plants. They also found an unidentified Ipomoea seed and planted Barringtonia asiatica , an Indo-Pacific beach tree, which did not survive. The vegetation in 1923 was restricted to tiny areas. By 1943, much of the island had sparse vegetation, and thickets of Scaevola taccada had developed along some beaches. This Scaevola is a wide-ranging Indo-Pacific seashore shrub, dispersed by both ocean currents and birds. By 1969, the vegetation was thick and included 13 species. Two of these had been deliberately planted: Casuarina equisetifolia and Chenopodium oahuense .

Pigs, Clipperton Island

(Sachet 1962)

Clipperton lies in the tropical eastern Pacific about 1,000 km off the coast of Mexico. This island consists mostly of a ring of coral sand and rubble surrounding a brackish lagoon. In the lagoon is a small outcrop of the volcanic rock on which the atoll is founded. When the island was first described in 1711, it had some low bushes on it, but by 1858 the vegetation had disappeared. The island then teemed with nesting seabirds and swarmed with land crabs.

Clipperton was occupied by guano diggers between about 1897 and 1917. Pigs were introduced by 1897 and about a dozen were left behind when the island was abandoned in 1917. The pigs survived on the abundant crabs and bird eggs.

A scientific expedition to Clipperton in 1958 found the island biota very different from that reported a century before. There were about 30 species of seed plants, mostly weedy grasses and dicot herbs, probably introduced by the guano diggers or later visitors. There were also masses of Ipomoea pes-caprae vines, probably derived from drift seeds. Various species of sedges had colonized the marshy lagoon edge, and various submerged aquatics, including Najas marina, Potamogeton pectinatus , and Ruppia maritima , grew

in the lagoon. Birds were much less abundant than in 1858, but various species of seabirds and shore birds were present. American coots were swimming in the lagoon with chicks; Sachet (1962) suggested that coots had brought seed of the sedges and aquatics. She also suggested that the feral pigs had been responsible for reducing the bird and crab populations and, in so doing, had permitted plant species to become established that had previously been barred from the island.

On Canton Atoll in the South Pacific, Degener and Degener (1974) noted that drift seeds of many species not present on the atoll commonly wash up on the beaches and germinate, only to be eaten by crabs; Ipomoea pes-caprae was specifically cited as an example. Clipperton has undoubtedly always been within the seed shadow of this beach morning glory, but could not escape the crabs until pigs entered the system. On Clipperton, pigs, functioning as carnivorous predators, played a role in vegetation change opposite to their role on many islands.

The 1958 expedition to Clipperton found 58 pigs hiding in the masses of beach morning glory; all 58 were killed on charges of molesting the nesting birds. The effects of their removal await study.

Cattle Rangeland, New Caledonia

(Barrau 1980)

In New Caledonia, traditional Melanesian shifting cultivation was displaced in the mid-nineteenth century by French colonial cattle ranches. In this seasonally dry tropical island, prehistoric slash and burn agriculture had probably been responsible for some expansion of savanna woodland and grassland at the expense of forest, but the Melanesians had no grazing animals and no incentive to convert forest to grassland. Savannas were more difficult to prepare for cultivation than forest fallow. Their irrigated terraces and yam mounds were permanent structures, but were periodically allowed to grow up to forest for later clearance by burning. The precolonial landscape had villages and gardens interspersed with stands of forest and patches of savanna woodland and grassland. The French could not see such a landscape without thinking of cattle ranching. By 1859, 1,000 head were imported from Australia, and by 1883, New Caledonia had 88,000 cattle. The Melanesians were driven out of large areas and their gardens converted to open range. Very quickly the vegetation became simplified, with overgrazing and spectacular erosion in some areas. There were die-offs of cattle during drought, and burning was extensively practiced to induce palatable regrowth. Though perennial grasses, particularly Imperata cylindria and Heteropogon contortus became dominant. A fire-resistant tree, Melaleuca leucadendron , originally confined to marsh margins, invaded more and more savanna areas. It was joined by

weedy shrubs from the American tropics, especially Lantana camara and Psidium guajava .

Desertification, Sahel

(Ibrahim 1980)

Between the Sahara and mesic Subsaharan Africa, the Sahel is a huge, semiarid savanna, a seasonally green grassland with scattered thorny acacias and other shrubs and trees. Since antiquity, most of it has been the domain of nomadic pastoral peoples moving northward during the rains, leaving the mud and disease of the south for the temporary grass and watering places of the Sahel. The nomads shared parts of the region with seminomadic or sedentary agriculturists, who planted millet, sesame, and other crops that required only brief rains. The economy and the natural vegetation were perhaps roughly in equilibrium, although under stress in drought years.

In the present century, with the advance of modern human and veterinary medicine and the drilling of water wells, this relative stability was changed. In North Darfur between 1917 and 1977, for example, human populations increased sixfold; sheep, goats, and camels more than ten-fold; and cattle twenty-fold. Starting in 1965, there was a 12-year period of below average rainfall. Similar droughts had often happened before, but not with the same grazing pressure. Unprecedented deterioration of the vegetation was widely evident by 1977, less in areas where traditional nomadic grazing had continued than where newly sedentary population had become concentrated around modern pumped wells. In a wide ring around these, all palatable grasses, including Cenchrus biflorus, Eragrostis tremula , and Aristida pallida , disappeared. Browsing coupled with fuel wood cutting eventually destroyed the acacias. In some places, removal of vegetation reactivated fossil dunes that had formed under an ancient, more arid climate. The newly bared areas were invaded by some native pioneer shrubs, such as Capparis decidua and Ziziphus spina-cristi , that had formerly been restricted to dunes and wadis. Sheep burr, Acanthospermum hispidum , an unpalatable annual composite native to tropical and subtropical America, has invaded overgrazed areas. The burr is carried in the coats of livestock. It is eaten by starving camels, donkeys, and goats where nothing else grows.

Overstocked Game Reserves, East and South Africa

(Barnes 1983; Cumming 1981; Owen-Smith 1981)

A serious problem has developed in the famous African wild animal reserves as large herbivore populations have increased above the carrying

capacity of the vegetation. Formerly free-ranging herds have been compressed into small remnants of their former territories.

In the Imfolozi Game Reserve in Natal, rhino-proof fences have confined a population of white rhinos, which has increased since 1930 from a few hundreds to thousands, reaching a density of over five per square kilometer. The reserve is shared with other ungulates, and their combined grazing has far exceeded the carrying capacity of the grassland. The formerly dominant tall grass, Themeda triandra , is gone from much of the area; it was partly replaced by creeping grasses, but much ground is bare and eroding. Because the sparse grass no longer carries fire, unpalatable woody plants have invaded it.

The problem is different for elephants because woody vegetation suffers most. Elephants not only break foliage and branches off trees for feed, but also damage or destroy trees for amusement. A single elephant may push over 1500 trees a year. After being decimated by ivory hunters for centuries, with the kill peaking in the mid-nineteenth century, elephant populations protected in reserves have rebounded dramatically and are now destroying their resources. In a study area in Zimbabwe, a woodland dominated by miombo, Brachystegia boehmii , lost 50% of its biomass in 4 years; in another study area, a miombo woodland was destroyed in 6 years. In a study area in Tanzania, during 5 years, a Commiphora ugogensis woodland lost 67% of its trees and a woodland of Acacia albida lost 40%; there was no tree regeneration in either area. In Kenya, elephants have been eliminating baobab, Adansonia digitata , from Tsavo National Park. Under primeval conditions, before people and their livestock had taken over most of the land, elephants would have moved on to greener browse after destroying a stand of trees. The open area could have become a grassland, maintained by fire and supporting herds of antelope and other grazing animals. In the absence of fire, trees would have recolonized until the elephants returned, in an endless cycle. The elephants have no place to go now; game managers have the horrible choice of letting them destroy their food supply and starve or shooting them wholesale.

Rise and Fall of Opuntia, Australia

(Hosking and Deighton 1979; Mann 1970; Osmond and Monro 1981)

About 30 species of cacti native to various regions of North, Central, and South America have become naturalized at least locally in Australia. Nine of these have become pests over considerable areas of southeastern Queensland and northern New South Wales. Australian botanists generally identify the worst pest cacti as belonging to two species, Opuntia stricta and O. inermis . American botanists generally consider O. inermis to be a synonym of O. stricta . What is called O. inermis in Australia may be called O. dillenii in the Americas. Whatever they are called, these prickly pears are native to

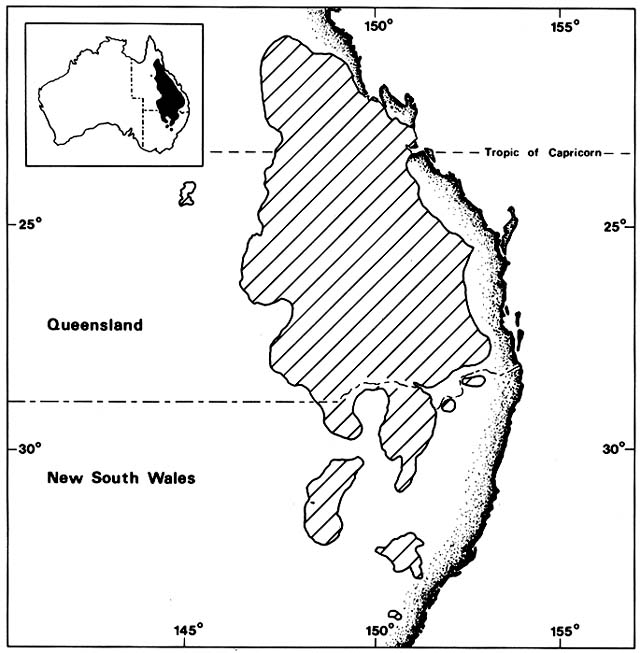

Figure 6. Maximum Range of Two Introduced Cacti (Opuntia stricta and O. inermis ) in Australia. Many plants

have become aggressive invaders when dispersed to regions free from their former parasites and herbivores.

Australia had no cacti until the nineteenth century when various New World species were introduced in cultivation.

Several of these escaped and spread rapidly in spite of control efforts. The map shows the combined ranges of the

two worst pest species in the early 1920s, before they were eliminated by insects introduced from South America.

(Adapted from Mann, 1970)

seashores of the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean. How and when they reached Australia is unknown, but by the mid-nineteenth century they were being widely planted for hedges by homesteaders in eastern Australia. Both spread on their own on the cattle and sheep ranges and were recognized as a nuisance by the 1880s. Dispersal was partly by vegetative propagation from pads adhering to livestock and partly by seed. The fruits were attractive to feral pigs, emus, and many other mammals and birds.

How successful the cacti would have been if the region had been ungrazed is uncertain. They spread mainly in open savanna woodlands, largely dominated by brigalow, Acacia harpophylla , and Casuarina spp., vegetation types in which grass fires were a normal part of the system. Hotter fires in ungrazed grass would presumably have been harder on the cacti than on the native plants. Although the two Opuntia species did naturalize in some coastal sites similar to their home habitats, their main infestations were inland, on both sides of the Great Dividing Range, up to elevations of about 800 m. The western limit was about 650 km from the coast. At their peak in the early 1920s, the two Opuntias infested about 25 million ha of land between 21° and 33°S latitude (fig. 6). Mechanical removal and chemical control cost more than the value of the land. Many sheep and cattle holdings were abandoned as useless.

In 1924, the Queensland government paid bounties for the slaughter of 335,000 emus and other birds blamed for spread of cactus seeds. The following year it was estimated that the cacti spread at an average rate of 100 ha/hr.

The tide was turned by biological control, an approach pioneered by Australian entomologists. Work had begun in 1912, when the Queensland government sent an expedition abroad to find cactus-feeding insects. They brought back a moth species native to Argentina, Cactoblastis cactorum , which unfortunately did not survive. They also imported cochineal bugs, Dactylopius spp., which were successfully reared, but work was suspended for the duration of World War I. In 1919, the Commonwealth Prickly Pear Board was set up. New expeditions to the Americas collected many kinds of cactus-feeding insects, including about 50 new to science. These were reared in quarantine and screened by starvation tests on economic plants. The first insects to be released were cochineal bugs, Dactylopius opuntiae , native to the southwestern United States. The bugs were successfully established on pest cacti in several Australian localities in 1921–1923; by 1924 patches of the cacti began to die. The government, enthusiastically helped by private initiative, spread the bugs along all the roads in the cactus-infested territory. The effect, however, was somewhat disappointing as cactus mortality was highly variable.

The catastrophic wiping out of the cacti was not accomplished by Dactylopius but by Cactoblastis cactorum . This moth was reimported from Argentina and finally released throughout the cactus-infested territory in 1926–1927. Moth eggs were supplied by the hundreds of millions free of charge

to landholders. The larvae fed on the cactus pads, riddling them with tunnels; most of the cacti promptly collapsed and died. By 1933, 90% of the Queensland cacti were gone. The crash of the cacti was followed by a crash of the insect population; then there was some cactus regeneration and resurgence of the insects. The cycles continued in constantly damping waves. At present, only a few cacti and their obligate parasites survive in scattered colonies, carrying on a stable hide and seek, host—predator relationship.

The story is not over. The tiger pear, Opuntia aurantiaca , native to Argentina and Uruguay, became a relatively minor pest in eastern Australia after 1911. It is currently spreading in east-central New South Wales in spite of large sums spent on attempted control. Cactoblastis larvae feed on the tiger pear, just as they do in their joint homeland, but they are not lethal to the cactus and do not stop its spread.

Comment

Pastoral peoples have commonly introduced domesticated pasture plants, both grasses and legumes, along with their livestock. This kind of comigration of symbiotically associated plants and animals occurred during European colonization of eastern North America and New Zealand, for instance. Since crop migrations are outside the scope of this book, the cases considered here follow other patterns.

Many cases have involved turning domestic animals out to shift for themselves on wild vegetation composed of species they had never met before. When this was done on islands that had previously lacked large herbivores, the effect on vegetation was catastrophic. There are many cases other than those discussed above; three additional examples on uninhabited islands can be cited. Ilha da Trindade in the tropical South Atlantic had forests that were destroyed by goats and pigs liberated by the famous scientist, Edmond Halley, in 1700 (Eyde and Olson 1983). Macauley Island in the Kermadec group in the temperate South Pacific had several dominant forest tree species that were exterminated by goats and pigs liberated in the early nineteenth century (Sykes 1969). Lastly, Rabbit Island, located 3 km off the Australian mainland in Bass Strait, acquired its rabbits in the mid-nineteenth century. The exterminated most of the flora. After the rabbits were in turn exterminated in 1960, plant recolonization from the mainland was rapid. The number of native species in the flora increased from 20 in 1960 to 49 in 1980 (Norman and Harris 1981). The losses of plants in these three cases may be partly attributable to island plants being poorly adapted to cope with herbivory, but they can probably be mainly blamed on uncontrolled growth of animal populations. Feral livestock on islands have commonly been free

from diseases as well as predation. The ultimate control on their populations is starvation.

Recent introduction of domestic herbivores to new continents, specifically Australia and the Americas, has also had catastrophic effects. Ecosystems with rough equilibrium between native plants, herbivores, and predators were replaced with new systems in which the predators were eliminated and grazing pressure increased by orders of magnitude. Although the native floras had coevolved with herbivores, the plants were unprepared for the escalated consumption, and the more palatable species generally retreated from large areas. In southwestern North America, various wild plants that were formerly gathered in quantity for food by the Indians are now extinct over large regions; some survive only where protected from grazing (Bohrer 1978).

The other side of the coin is the advance of plant species that benefit, in one way or another, from increased herbivory. Some of these are native pioneers from nearby riparian, coastal, and other open sites that invade areas formerly closed to them. With overgrazing, opening up of bare ground and reduction of burning are so tightly correlated that it is often hard to sort out their roles in allowing these advances. This question arises in many cases in addition to those cited above, for example, in advances of mesquite (Prosopis spp.) in overgrazed grasslands in southwestern North America (Fisher 1977; Gilbert and Moore 1985) and in Argentina (D'Antoni and Solbrig 1977).

Along with the native pioneers, exotic invaders usually thrive with increased grazing. Occasionally, some species arrive in the coats of the introduced livestock, but usually they arrive later by accidental or deliberate human dispersal. It is commonly assumed that this is because they had to await habitat disturbance, but this is not always proven. In western North America, for example, Bromus spp. and other Eurasian annuals have spread on both overgrazed and undisturbed ranges. These annuals grow so fast and abundantly in the spring that they are only partly consumed by livestock. Unpalatable when mature and dry, they accumulate as dead fuel. Commonly this has resulted in reversal of the advance of fire-sensitive native species after grazing removed the original fire-carrying native grasses. Furthermore, in the Mojave Desert of California, these Eurasian annuals have invaded ungrazed regions dominated by creosote bush, Larrea divaricata , and cacti, Opuntia spp., which were originally fireproof because of sparse herb cover. Repeated burns decimate and may eventually eliminate native shrubs.

Drastic effects of increased herbivory are not confined to islands and continents where herbivores are invaders. The African examples discussed above show that even where plant and animal species have lived together since prehistoric time, recent human-controlled buildup of animal populations has also resulted in local retreats and advances of native species and invasion of exotic, unpalatable species.