12

The Larger Stage

For Douglas Hyde, preoccupied with the new Irish theater, the success of his plays, and the growth of the Gaelic League, recognition that some things were going awry dawned slowly. Between 1893 and 1899 he had come to think of himself as the happiest of men. On January 17, 1900, when he turned forty, he was, in the opinion of those who knew him well, a practical, adaptable, resourceful, and optimistic leader. His best asset, as described by one acquaintance, was his "superb and adroit capacity for making the best of an opportunity." He might have been more wary of the twentieth century had flashes of lightning or claps of thunder instead of minor cracks and distant rumblings signaled that his life was about to change.

There had been, for example, the hearings before the Royal Commission on Intermediate Education in 1899. Everyone had thought that their purpose was to strengthen an 1878 ruling concerning instruction in Irish that was not being enforced. Then Mahaffy, attacking the small ground that had been won twenty-one years before by the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language, had suddenly succeeded in changing the issue to whether there should be such a ruling at all. Momentarily caught off balance, complainant had unexpectedly become defendant, but Hyde had recovered quickly and marshaled such support from so many distinguished scholars that in the end the Intermediate Education (Ireland) Amendment Act of 1900 seemed to have put the Irish language in a better position than ever before.

Then, even as Hyde had incorporated this experience into the

speeches he made, welcoming new branches into the League—even as he was editing for a Gaelic League pamphlet the arguments in favor of the language that he and his blue-ribbon referees had presented to the commission—there were distant rumblings. They came from restless leaguers who, agreeing with Hyde's estimate of the league's strength and accomplishments, challenged his continuing policy of nonconfrontation with British authorities. True, they said, nine men had met on July 31, 1893, in Martin Kelly's rooms at 9 Lower Sackville Street to found the Gaelic League, and current membership stood at between 10,000 and 12,000. Yes, even with only nine members the league had not defined itself narrowly but had sought to represent a cross section of Irish society, and now at the turn of the century its strength was its broad base of Catholics and Protestants, nationalists and Unionists, landlords and tenants, civil servants and schoolteachers, old and young, women and men, all working together. And yes, when these women and men looked at what they had accomplished in seven short years, what they saw, as Hyde proclaimed, was a network of organizers, traveling Irish teachers, strong local committees, and rank-and-file members who had by their own efforts set up classes in spoken Irish and Irish music, dancing, and sports. It was indeed the general membership, these leaguers confirmed, that had fostered the spread of literacy in Irish in both Irish-speaking and English-speaking areas. It was they who, working together, had established a publishing program that included a league newspaper, league texts to help them learn, improve their Irish, and teach their families and neighbors, and league pamphlets that countered the propaganda of their enemies and kept their members informed. Through local and regional feiseanna and through the annual oireachtas the league had brought to its members enjoyment and pride in being Irish and living an Irish life. If Hyde himself had said that all these things were so, why, these discontented leaguers asked, did he insist that they must continue to avoid confrontation with the British authorities?

Many leaguers could not understand why Hyde opposed the mail-in-Irish campaign. They deeply resented the ruling enforced by the British postal system in Ireland that all letters and packets must be addressed in English. Speaking from his lecture platform, Hyde had urged his fellow members of the league to keep alive their language and culture, to speak Irish among themselves at every opportunity, to sing Irish songs and tell Irish stories, and even to write to each other in Irish. But, they asked, must they then send their Irish letters to each other in enve-

lopes addressed in English? If the Gaelic League could fight for education in Irish in the schools, why not, they asked, fight for the right to send letters and packets addressed in Irish through the Post Office?

For Hyde the answer was, as the old storytellers would say, ní hansa —not difficult to relate. The Intermediate Education (Ireland) Amendment Act had been worth the risks presented by the royal commission hearings. Victory had assured the Irish people that within the educational system Irish could grow and spread in response to popular demand. Whatever it had cost to wage the battle against the Trinity dons had been an investment in shaping the attitudes of the young and therefore the future of the Irish nation. He was not willing, however, to jeopardize the league's prospering position for any lesser cause, especially one that could be used against them to their detriment. To be sure, the mail-in-Irish campaign that restless leaguers were advocating (indeed, already had begun on their own) had raised an issue that some day would have to be confronted. But if the Post Office refused to handle letters and packets addressed in Irish and league members insisted that only Irish be used on league mail, the result would be a disruption of communications among league branches and a crippling of league efforts to raise much-needed funds.

Earnest leaguers eager for another victory could not understand such caution in the man who had been a founder of their organization and the author of its policy of deanglicization, especially as among themselves they were discovering new, young leaders who disagreed with him. They continued their mail-in-Irish campaign. It was the first serious challenge to Hyde's policies and leadership.

What Hyde understood, of course, but could not convince protesting leaguers to accept, was that by insisting on the right to address envelopes in Irish, they were touching a sensitive nerve that affected not just British government in Ireland but the entire British Empire. One of the strengths Hyde brought to his position as president of the league was that he had only to repress An Craoibhin and assume momentarily the persona of the son of the rector of Frenchpark to see how the Ascendancy viewed such matters. For decades, for example, as he knew well, the British postal system had prided itself on the speed and efficiency of its worldwide service. It was the primary channel of communication in the largest and most widely dispersed bureaucracy the world had ever known. It employed thousands of civil servants with titles such as postmaster, sub-postmaster, inspector, surveyor, surveyor's assistant, clerk, telegrapher, and sorter who obtained their jobs through a political

patronage system that rewarded loyal citizens of country, colony, and distant outpost. It was an instrument of British policy through which the government provided support for factions and classes that it wanted to foster and denied it to those it wanted to weaken or render invisible. There was no doubt that a campaign to allow addressing in Irish would be seen by the Post Office as an overt threat to the entire system in all its ramifications. Bilingualism in Ireland was not British policy. Irish might be taught in schools—a postal clerk who knew Irish might be useful in an Irish-speaking area when a monolingual person needed assistance or the odd letter addressed in Irish slipped through the cracks—but it was not officially recognized for government use. If the Irish were to win the right to mail letters and packets addressed in Irish within Ireland, it would mean that they would be able to send such letters and packets through the entire British postal system. The Post Office would have to hire people competent in reading and writing Irish not just to assist an occasional customer but to sort and deliver mail. It would have to violate government policy, which did not recognize Irish as an official language.

Leaders of the mail-in-Irish campaign were not persuaded by Hyde's argument that because the league's policy of avoiding direct confrontation with British authorities had proved so successful in the past, it should not be abandoned in the future. Many openly resented his declarations on the subject. Underneath all, some quietly reminded others, An Craoibhin was, of course, not really one of them but the son of the Protestant rector of Frenchpark. He was, moreover, a kinsman of Lord de Freyne, whose treatment of the Frenchpark tenantry had become a public scandal. And in his youth he had been a protégé of Charles Owen O'Conor Don, the man descended from an ancient and honorable Celtic family who once had had the respect of his countrymen but now, in his opposition to land reform and tenant relief, revealed, they said bitterly, the soul of a landlord. It was not that they suspected Hyde's loyalty—they were confident that he was a committed nationalist (many said he was a sworn Fenian)—but all the same, they told each other, there was no mistaking the fact that he still had a lot of the country squire in him. How much further could they follow him, they asked themselves, if he continued to insist on avoiding open confrontation?

At home in his study at Ratra, Douglas Hyde was disturbed by the distrust and dissension that seemed to be increasing all around him. At the same time he was preoccupied with the implications of Lucy's persistent illnesses. Through the winter, spring, and summer of 1900 her

condition had steadily declined. Her numerous symptoms, which had puzzled other doctors, had prompted Dr. Sigerson to prescribe a bewildering variety of remedies, including steaming, tincture of iodine, Vichy water, poultices of turpentine and mustard, a tonic, and a half-drop of belladonna every quarter hour until six or eight in the evening. What was to become of her, of him, of their children, and their home at Ratra, Hyde asked himself, if she continued in this semi-invalid state? He had been assured that there was no question of life or death. That, at least, was a comfort. But poor Lucy was so miserable most of the time. Where would he turn if Sigerson's prescriptions did not bring some relief? In December 1900 Hyde sent Lady Gregory a packet of his early work: "Irish songs I made, some of them twenty years ago, and printed in various places." With it was a wistful request that she, his trusted friend, keep these manuscripts for him until such time as he felt he could retrieve them, for he liked to think that he might rewrite and republish them some day.

Three months later, on Monday, March 25, 1901, the skirmishing of the mail-in-Irish leaguers expanded into what became a long and costly battle between the Post Office and the Gaelic League. The first shot was fired when Thomas O'Donnell, an Irish M.P., stood up in the House and asked why a circular had been issued to Post Office officials, directing them to regard all letters with Irish superscriptions as insufficiently addressed. O'Donnell, who previously had signed his name in Irish on the parliamentary roll and had attempted to give his maiden speech in Irish, had not long to wait for the government's reply. Austen Chamberlain, secretary of the treasury, later postmaster general, condescendingly explained that the authorities presumed that senders of such letters in Great Britain were able to write directions on their envelopes in English. It was to those patrons, he said, that the circular had referred. He conceded, however, that letters bearing addresses in Irish that were mailed from Irish-speaking districts would be delivered. Not satisfied, O'Donnell pressed the government with a second question: "Does the honorable gentleman know that there are thousands of Irishmen who prefer to write their letters in Irish?" Chamberlain replied that anyone might write in Irish if he pleased, but that the Post Office required that all addresses be written in English "by those who presumably know English."

Aware that O'Donnell's question probably signaled an intensification of the mail-in-Irish agitation which the Post Office had tried to ignore by treating it as a series of unrelated incidents, postal authorities issued

instructions that henceforth all press reports on the controversy together with internal Post Office correspondence, directives, and memoranda be preserved and filed. In the London Post Office an anonymous civil servant was assigned responsibility for monitoring the daily British and Irish press, underlining or bracketing with blue pencil pertinent passages of all news items pertaining to the mail-in-Irish agitation, cutting out and pasting these items in bulky folders labeled "Correspondence Addressed in Erse," and filing these folders with others labeled "Irish Minutes." As Hyde had warned, no longer would any action of the Gaelic League go unnoticed or unrecorded. It was only a matter of time before a second order of surveillance was issued by Dublin Castle.

Meanwhile, in a written answer to O'Donnell's query (copies of which were dispatched to postmasters in Manchester, Sheffield, Nottingham, Bradford, and other cities with large Irish colonies), the postmaster general rejected "special arrangements for the translation of addresses in Irish into English, especially in the case of letters posted in England." Like Chamberlain, he offered a concession: that "in the event of a letter in Irish passing through an office where it can be deciphered, the address shall be translated into English and the letter sent on to its destination."

Even as this reply to O'Donnell was written and publicly distributed, it was underscored by the internal circulation of an unsigned memorandum based on the only facts that mattered to the Post Office: the number of people in Ireland who could write Irish and only Irish. Armed with statistics from the 1891 Statesman's Yearbook that established this figure at 40,000, the unnamed author declared that this was not a constituency whose demands justified changing rules that had earned the Post Office its name for economy and efficiency. Questioning whether special arrangements should be made for educated people who could just as well write in English, he recommended that letters addressed in Irish be treated as undeliverable and dealt with in the Returned Letters Office. This was, in the writer's opinion, the simple solution to the problem—the same solution, he noted, that was used in Germany where writers understood that letters addressed in Polish would be treated as undeliverable. As for the matter of requiring Post Office appointees to have a knowledge of Irish, it would so limit the field of choice, he believed, "as in some instances to raise a grave danger of leaving the Department without any candidate fit for appointment."

This unsigned memorandum established official Post Office policy for years to come.

The mail-in-Irish campaign continued. On October 13, 1901, Mr. J. MacNamee of Navan complained to the Post Office that the local postmaster had refused to cash a postal money order. Always quick to follow up complaints, the Post Office queried Navan. On October 18 the inspector reported that MacNamee had endorsed his postal order "with his signature written in Irish characters" and, on being asked, had refused to sign his name in English. Furthermore, MacNamee had stated that he was making a test case, that he intended to have the matter taken up by "the central executive of the Gaelic League," and that in his opinion postal officers should understand the Irish language. The Navan report concluded: "None of the officers at Navan are conversant with the Irish language." Not until December 23, 1901—and then only after prolonged consultation among the Post Office, the comptroller, and the accountant general—was it decided that MacNamee's order could be paid if the words "described as J. MacNamee" were added below his Irish signature.

The first Gaelic League "Language Week" was held in March 1902 in conjunction with a long procession commemorating St. Patrick's Day. Hyde, of course, was among the principal speakers. He was relieved that little was said about the mail-in-Irish campaign, which he still hoped to confine before it brought the trouble he had predicted. His main concern was the annual fund-raising drive set for this time of year and conducted largely through the mails. Sporadic complaints concerning the handling of letters and packets addressed in Irish continued to be received by the Post Office. All were handled routinely, with reference to the official policy statement drawn up in 1901. On Monday, November 6, 1902, an Irish M.P. by the name of Tully rose in the House to ask the postmaster-general whether, given complaints from the Gaelic League in London about nondelivery of letters and postcards addressed in Irish in Sligo, he would "consider the advisability of insisting on persons obtaining Post Office appointments in Ireland having some knowledge of the Irish language." Back came the unequivocal answer: "In my opinion there is no sufficient reason for requiring a knowledge of the Irish language from entrants into the Post Office service in Ireland." On Monday, December 1, 1902, the subject came up again when Patrick O'Brien, M.P., asked if the postmaster general would supply copies of an Irish dictionary to each post office to

facilitate delivery of letters in Irish. Chamberlain's response was again immediate: "I do not think the circumstances are such as to justify the provision of Irish dictionaries at Post Offices."

By March 1903 Dublin Castle had begun to keep its own files on Douglas Hyde and other "key agitators" of the Gaelic League. Long clippings from the Independent and the Weekly Freeman containing passages from their speeches underlined in blue pencil were added to a file labeled "Irish News Cuttings." From September through November the Post Office was kept busy investigating the complaint of a leaguer from Galway, the Reverend A. J. Considine, concerning a postal money order that a clerk had refused to cash because the order was made out in some form of Irish that he could not understand. After investigation, the Galway Post Office reported to London that the Irish in Considine's order was unintelligible—and that he had admitted that his was a test case. On December 2, 1903, a postal service customer by the name of Hugh Graham complained in a letter written in Irish to the secretary of the Dublin Post Office that the postmistress of his branch would not release a registered letter posted to him in England after he had signed his name in Irish on the receipt. "Is it not proper, allowable and right for an Irishman to write down his name correctly in his own language?" asked Graham. During the same month Henry Morris, Gaelic League organizer in the Dundalk area, editor of the Gaelic department of the Dundalk Democrat , and Hyde's close friend (albeit one who disagreed with him on this matter), published some words of advice to leaguers engaged in the mail-in-Irish campaign. Their twin aims, he declared, should be recognition of Irish as a national language and the addition of Irish to the list of obligatory subjects required of all candidates for all departments of the postal service. To achieve these he recommended increased use of Irish, since Post Office policies were based on statistical evidence of language use: "Those . . . who can write the whole letter in Irish should do so, but those who cannot do that much should at least address the letter in Irish—and in Irish only—except in cases where great dispatch is necessary."

Pleased with their escalating provocation and unaware of the files that were being kept in the London and Dublin headquarters of the Post Office and in Dublin Castle, leaders of the mail-in-Irish campaign, now in its fourth year, did not fail to draw attention to the fact that it had not resulted in the kind of crushing retaliation predicted by Douglas Hyde. Even the sallies on the floor of Parliament had evoked not

the outraged protest or condescending rebuke that might have been expected but only a matter-of-fact repetition of official policy. The British government had not mellowed; it was otherwise occupied. Cabinet minutes from August 1899 through 1903 reflect continuing concern over the conduct of the Boer War, the Boxer Rebellion, the negotiation of an agreement with the United States to create a transoceanic canal in central America, and the possibility of a Russo-Japanese war. When Parliament did turn its attention to Ireland, the debate was usually over the Land Purchase Acts and other legislation concerning the Land Question.

Throughout the years 1900 to 1905 the Land Question also concerned Douglas Hyde on a personal level. The de Freyne estate in Frenchpark had become a battleground as Lord de Freyne, irate over land reform, infuriated by tenants who were withholding their rents, enraged by the "interference" of the United Irish League in his disputes with these tenants, carried out draconian evictions that were fully and graphically reported in London, Dublin, and provincial newspapers. In 1904 the Congested Districts Board, with its authority to buy up and redistribute uneconomical holdings, moved against de Freyne. Although no doubt spurred by the evictions, the action of the Congested Districts Board was not necessarily punitive but merely part of a process of land reform that had started in 1870. Despite help offered through O'Conor Don by the Committee of Landlords, which saw the reform process as disastrous to Ireland's agricultural economy, de Freyne finally gave up and set a price at which he was willing to sell his tenanted and bog land. It was only a matter of a very short time, Hyde knew, before the Congested Districts Board would be pressing him to buy or leave Ratra. How could he even contemplate parting from these meadows and fields, the lake, those distant hills? Lucy was insisting that they must go.

Meanwhile, the Gaelic League was faced with a funding crisis. The situation could not be blamed entirely or even chiefly on the mail-in-Irish campaign, but it had not helped. Even Henry Morris had advised that urgent letters should be addressed in English, not Irish, but having committed themselves to the mail-in-Irish campaign, league fund-raisers were addressing solicitations in Irish, with consequent incidents of nondelivery and delay. The biggest drain on the budget, however, as Hyde had written in October 1903 to his friend William Bulfin, Irish emigré to Argentina and publisher and editor of the Buenos Aires Southern Cross , was an increase in workload that required additional paid staff.

League membership had passed the 50,000 mark and was still growing. Full-time organizers were now needed to handle the paperwork involved in adding new branches in Ireland and affiliates abroad. The subsequent demand for new language books had resulted in larger and larger printing costs. Determined that all 1903 debts would be paid before the end of the league's fiscal year in February and the new collection in March, Hyde asked Bulfin if there was any possibility of obtaining a second contribution from the sources usually tapped by the Southern Cross . In a speech to a large audience in Dundalk in February 1904, Hyde proclaimed what he called "the Battle of Ireland." The underlying subject was the funding crisis—his point was that growth and achievement were costing more money than was being received—but his appeal stressed what the league had been accomplishing. The mail-in-Irish campaign was now frankly acknowledged to be one of the league's activities.

The fact was that, measured by the number of items addressed in Irish that were being processed by the Post Office, the mail-in-Irish campaign actually was succeeding. Official British Post Office policy had not changed; it remained the same, in fact, under three postmasters general (the Marquess of Londonderry, 1900–1902; Austen Chamberlain, 1902–1903; Lord Stanley, 1903–1905) and their secretaries (Sir George Murray, 1899–1903 and Sir H. Babington Smith, 1903–1910). Official communications consistently and publicly maintained that there was no reason why the workings of the British postal system should be jeopardized for the purpose of serving a handful of Irish monoglots. But the Post Office had not achieved its worldwide reputation for speed and efficiency without having had to make practical adjustments. In the case of Irish this meant that by early 1905, with the Dublin Post Office receiving over two hundred letters addressed in Irish daily, Charles Sanderson, the Dublin postmaster, had taken from their regular assignments four junior clerks and telegraphists with "an adequate knowledge of the language" and set them to work translating Irish addresses. In a letter to his superior, however, Sanderson expressed concern that these measures would not be sufficient if, as expected, he received a huge mailing addressed in Irish "by a particular organisation." The effect, he warned, could be costly and surely would cause delays.

The organization to which Sanderson was referring was of course the Gaelic League; the huge mailing that he was correctly anticipating was the annual "collection," which provided the greater part of the

league's financial support. Hyde had emphasized to Patrick O'Daly, secretary of the league since 1901, that this year more than ever a successful collection was a vital need. Even as Sanderson wrote, O'Daly was halfway through the task of supervising the assembly of hundreds of packets containing announcements of Language Week and the fund-raising kits to be used by canvassers in the local branches. By the first week of March, O'Daly's crew had addressed 600 parcels with the recipient's name and address in Irish. But if at times the Post Office might bend, it would not allow itself to be broken. On March 1 the Irish secretary of the Post Office wrote to his British counterpart in London: "It must of course be borne in mind that there is no necessity for these letters to be addressed in Gaelic. There is no pretense in Dublin at any rate that Gaelic is a common language. So far as necessity goes the letters might just as well be addressed in Greek or Hebrew."

Since parcels addressed in Irish had been accepted at the General Post Office earlier in the year, O'Daly was outraged when several hundred parcels were refused on the grounds that they were unacceptable for mailing and would have to be readdressed in English. O'Daly wired the Dublin postmaster on March 7: "250 parcels addressed in Irish refused last night are lying here. Will they be accepted today?" His reply came from London: "Parcels addressed in Irish cannot be accepted without English translation of addresses." Indignant, both O'Daly and Hyde refused to believe that the problem was caused by the addresses in Irish. The Post Office officials were fully aware of the purpose of the contents of the packets, Hyde declared. These officials also knew that if the collection was destroyed the league would be left virtually without the money it required for operating expenses for the coming year. For him there was no doubt: the sudden imposition of a work-to-rule order was made "with ill will and full knowledge." As the rule, however, was being applied only to bulk mailings, O'Daly sent out a call for Irish speakers to come to an emergency meeting. Two hundred responded. Each was given a packet and all went down to the main post office. "They took over the place entirely," O'Daly reported. "Each Irish speaker there offered his own packet to the officer inside. Each person did this one after the other, calmly and quietly in Irish. No more work was done in the Post Office while this was going on. It put a stop to the work that is the ordinary business for an hour, the place was so busy."

Realizing, however, that a prolonged impasse with the Post Office could destroy the 1905 collection and surely would raise costs (the rates

for individual mailings were greater than those for bulk mailing), Hyde decided to try personal diplomacy. He immediately sought an interview with Lord Stanley, the postmaster general, in London. Using his best Ascendancy manners, Hyde was persuasive and persistent; cloaked in governmental invulnerability, Stanley was courteous and attentive. Stanley promised nothing.

Although his interview with Stanley came to little, Hyde was quick to seize the opportunity to generate public sympathy for the league. The motives to which he had ascribed the Post Office's refusal to handle the bulk mailing addressed in Irish already had made headlines in Dublin and London newspapers. In an interview with the Irish Independent of March 3, 1905 (duly cut and pasted in the Post Office file labeled "Correspondence Addressed in Erse"), Hyde struck back: "It is nothing short of a scandal that the Post Office authorities have not made Irish a subject of examination for Post Office officials considering the number of letters that pass through the post addressed in Irish. . . . I hope the authorities will soon discontinue their foolish opposition, which will serve no good purpose but to irritate the public."

On March 4 the Freeman's Journal printed a lengthy account of the battle between the Post Office and the league, stressing the capriciousness of the postal authorities who had, after initial refusal, reversed themselves and accepted six or seven packets, only to reverse themselves again and refuse on the next day over two hundred parcels that had been picked up by Post Office van. According to the writer of the article, the reversal had occurred when a minor official in the Dublin post office had been overruled by the Irish secretary who, in a memo to London sent on March 4, had complained that "the whole thing is an attempt to force the Department into having a Gaelic-speaking staff throughout the country, a matter as impracticable as useless and wasteful."

On March 6 the matter reached Parliament where Boland, an Irish M.P., asked if the Gaelic League parcels had been refused at the order of the postmaster general or without his knowledge. Pursuing the same line of questioning, John Redmond rose to inquire whether the postmaster general knew that the Gaelic League had been handicapped by this refusal, because the packets contained material about the annual collection. He also asked flatly if, now that the matter had been brought to his attention, the postmaster general could assure him that the parcels in dispute would be dispatched in due course.

By March 12, the day set for the Language Week procession, the

conflict between the Gaelic League and the Post Office had attracted the attention of thousands. Since the government crackdown already had affected the annual collection, Hyde's strategy was to win at least a propaganda victory. He spoke openly before crowds and to newspaper reporters of the clash between the Post Office and the language movement. The result, reported the Freeman's Journal, was "one of the most imposing public demonstrations that . . . ever passed through the streets of Dublin." Editorializing on the situation on March 13, the Freeman's Journal continued:

No greater proof could have been given of the strength of the language movement. . . . There was hardly any element of Irish life that was not yesterday influentially represented. . . . The aggressive and bitter vendetta of the English Post Office Department against the movement gave the opportunity for a really most extraordinary and effective promulgation of public opinion.

Placards and bannerettes proclaimed, "No Surrender to the Post Office. Address all your parcels and letters in Irish." When the Irish-language section passed the General Post Office, the procession paused to render a rousing chorus of "A Nation Once Again." On the side of a tableau wagon someone had scribbled, at the bottom of a prominently displayed white banner bearing the familiar red insignia of the Post Office over the monogram of Edward VII, "We Don't Like Irish." On this same open wagon an Irishman ("in typical Gaelic costume," according to the Freeman's Journal ) and a Post Office clerk played a perpetual Beckettian dumbshow. The Irishman picked up a parcel and offered it to the clerk at the counter, who looked at the parcel, shook his head, and handed it back to the Irishman, who immediately picked up another parcel and offered it to the clerk, who shook his head, and handed it back to the Irishman: "all most effective and excellent comedy at the expense of the Post Office," the Freeman's Journal reported.

The procession wound its way to Smithfield where Hyde shared the speaker's platform with the archbishop of Dublin. Standing before a shouting, cheering crowd, smiling and waving as he waited for a quiet moment to begin his speech, Hyde began slowly: "First—First—First, I want to tell you—First I want to tell you of—First I want to tell you of the wonderfully mean and miserable, petty and paltry attempt that was made to spoil our collection last week by the General Post Office." He paused. The crowd groaned loudly. He accused the Post Office of trying to break the spirit of the league. The crowd booed. He described his attempt to negotiate with Stanley:

I asked . . . to make Irish not, mind you, a compulsory subject at all, but an optional subject for entry into the Post Office. And what was their answer? They not only refused me, but they have made Irish penal in the Post Office. They will not be allowed to do it. There are only seventeen letters in the Irish alphabet, and there are only three of those that are not the same as in English, and the Post Office people are not able to learn those three.

Loud laughter was followed by more cheers. "This struggle was forced upon us by them and was none of our making or our seeking. It has been forced upon us. We have no desire whatever to quarrel with these people. It is they themselves who have brought the quarrel upon themselves." Amid laughter and applause the archbishop, following Hyde, announced that he himself would not have attended the Language Week celebration but for the Post Office refusal that had threatened to make the League's procession a failure. There was more laughter and cheering as everyone, looking around, saw nothing but crowds in every direction.

On March 13 the secretary of the Post Office for Ireland sent London his report accompanied by the account in the Freeman's Journal of the procession and rally. "It is to be regretted," he wrote, providing a fitting final line to the comedy, "that the action of the Department should be looked on as hostile to the League itself. What the promoters of the movement fail to understand is that a translation must be affixed to a parcel before dispatch and there is no reason why the additional work should be thrown on the Department."

Five days later the words of Henry Morris writing from Dundalk were more somber.

The Post Office has declared war against the Irish language and the Gaelic League. The Gaelic League could not refuse to accept this challenge. So now it behooves every Gaelic Leaguer to take a share in the battle. . . . Irish Ireland insists that Irish . . . being the national Language . . . be dealt with in the Post Office exactly on a par with English.

The public, Morris avowed, must force the Post Office to provide a bilingual staff. It must address all letters, cards, telegrams, and parcels in Irish until the Post Office is blocked and everywhere there is evidence of chaos and delay. Readers must complain in writing (preferably in Irish) to the secretary of the Post Office each time a delayed piece of mail is received. They must demand an explanation for the delay. (What Morris knew was that Post Office rules required a written response to every complaint, including those in Irish.) All these moves should be

followed, concluded Morris, "for the express purpose of asserting our own right to use our own language in our own country. Dr. Hyde has sounded the tocsin . . . and every Irish Irelander should take a genuine part in the fray."

By April 2 the continuing pressure on the Post Office had begun to have its effect. The number of letters addressed in Irish that passed through the Dublin Post Office had climbed from 313 on March 20 to 600 on March 26. Within a single week over thirty hours had been spent translating a total of 2,498 items from Irish to English. In his 1905 report to London the Irish Secretary warned that the dispute had to be settled in some way, as the work of translation had become "formidable." Yet he did not know what to propose, for if anyone were specially assigned to translation as his regular duty, he had no doubt that the Gaelic Leaguers would consider that they had gained their case in principle and would press home their advantage by multiplying the number of letters addressed in Irish. The secretary assured his superior in London that "the general expression of feeling which reaches me is a hope that the Postmaster-General will not give way in the matter."

Believing that the time was right for such communication, on April 3 Hyde wrote two letters for delivery to Lord Stanley. The first was typed. He called it his "official letter." The second, a "private letter," was written in his own hand. In the five-page "official" letter, a combination of a carrot and stick, Hyde repeated the arguments he had made to Stanley in person but referred to the case of the packets addressed in Irish only once. He focused instead on acceptance of Irish as an optional subject for Post Office examinations. He argued that Irish already was accepted as either a compulsory or optional subject in many business, professional, and educational areas of Irish life. To facilitate the work of the Post Office, he offered to send Stanley copies of a directory compiled by the league of postal towns and stations in Ireland which gave on one side the "correct" Irish form and on the other "the corrupt or translated forms by which these places are known." He also offered Stanley a Gaelic League volume in press that showed the correct form of Irish surnames being widely adopted. "With these two volumes at its disposal," he declared, "the Post Office will experience little or no difficulty dealing with the new order of things." Hyde closed with the pointed reminder that 50,000 people had marched in the Language Week procession of March 12, forming a line witnessed by 200,000 people that wound through the streets for two miles—proof "that the whole country is solid behind Dublin in respectfully making

this . . . reasonable request of the Post Office." "We feel confident," he concluded pointedly, "that it is only necessary to put these plain facts before you for your compliance."

In sharp contrast (Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was a story that Hyde found amusing) was the conciliatory tone of the handwritten "private letter," which expressed the hope that Lord Stanley, without any inconvenience to himself or to the working of the Post Office, might find it possible to comply with Hyde's "requests." "I beg of you," wrote Hyde, his sharply slanted writing bearing uphill, "not to treat this question from the narrow point of view of the Post Office, but from the standpoint of a statesman." If the Post Office rejected the league's demands, Hyde wrote,

I see with alarm the prospect of an agitation in Ireland which however it may end will at least have a certain effect . . . to still further alienate English public opinion from the English government, and to turn into opponents of the government a great portion of the Gaelic League who have up to this never touched politics in any way but have turned into a wholly laudable channel a very great deal of energy which would but for it have been used in a different direction.

Calling for use of "the oiled feather on both sides and a little give and take," Hyde warned Stanley that if the controversy were not stopped, it could prove "a very nasty business later on"—one that might even turn the Gaelic League into a channel Hyde himself was most anxious to avoid. Clearly separating the Jekyll-and-Hyde alternatives he had offered, Hyde closed with the reminder that his handwritten letter was private, his typed letter official.

What Hyde could not know, of course, was that his "official" letter had confirmed the suspicions of the secretary of the Post Office for Ireland that the real issue was not the matter of whether the Post Office henceforth would allow letters and packets to be addressed in Irish but how the Post Office henceforth would be staffed. Six weeks passed before Hyde received Stanley's official reply rejecting all his proposals: the requirement that parcels and registered letters addressed in Irish be accompanied by an English translation stood; the request to make Irish an optional subject for Post Office candidates was denied; the demand that Irish-speaking postmasters be appointed in Irish-speaking districts was rejected. Ignoring Hyde's veiled threats and other ploys, Stanley's personal reply of May 15, 1905, was no less adamant: "I am afraid," he wrote, that "you must take the views that I expressed in my official letter as being the line of conduct which I propose to take with regard

Douglas Hyde at twenty. (Courtesy Sealy collection)

Hyde's sister, Annette (later Mrs. John Cambreth

Kane). (Courtesy Sealy collection)

Hyde's father, the Reverend Arthur Hyde, Jr.

(Courtesy Sealy collection)

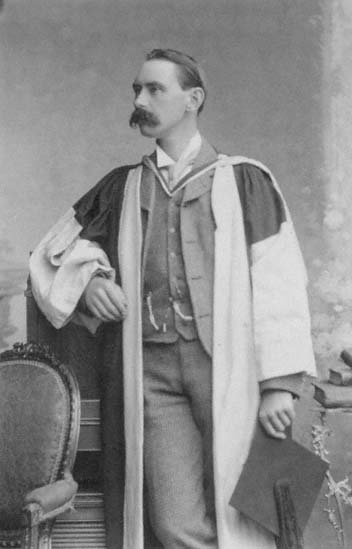

Dr. Douglas Hyde, Trinity scholar. (Courtesy Sealy collection)

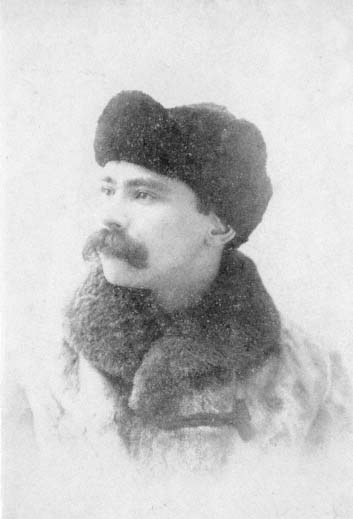

Hyde in New Brunswick, Canada (1890–91).

(Courtesy Sealy collection)

Lucy Cometina Kurtz, shortly before her marriage to

Douglas Hyde in 1893. (Courtesy Sealy collection)

Douglas Hyde with sister, Annette, and wife Lucy, in his carriage in front

of his county Roscommon residence, Ratra. (Courtesy Sealy collection)

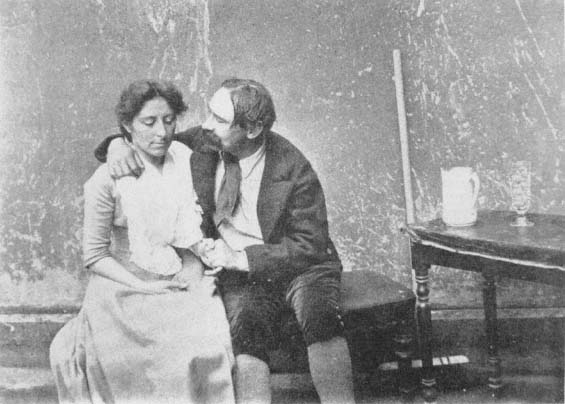

Douglas Hyde with Miss O'Kennedy, in "Casadh an tSúgáin" (The

Twisting of the Rope). (Courtesy Colin Smythe, Ltd.)

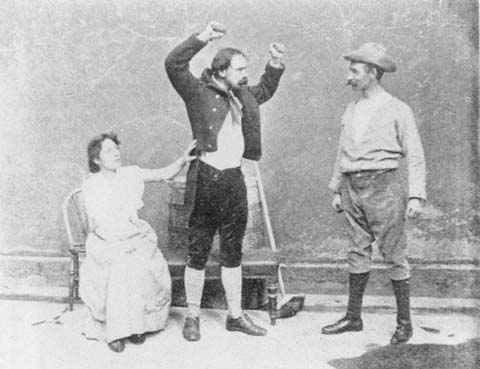

Douglas Hyde with Miss O'Kennedy and Teig O'Donahue, in "Casadh an tSúgáin"

(The Twisting of the Rope). (Courtesy Colin Smythe, Ltd.)

Douglas Hyde at Ratra, between daughters Una (left) and Nuala

(right), with family dog. (Courtesy Sealy collection)

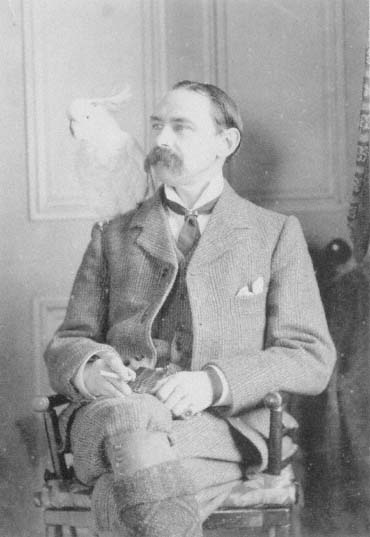

Douglas Hyde with pet cockatoo. (Courtesy Sealy collection)

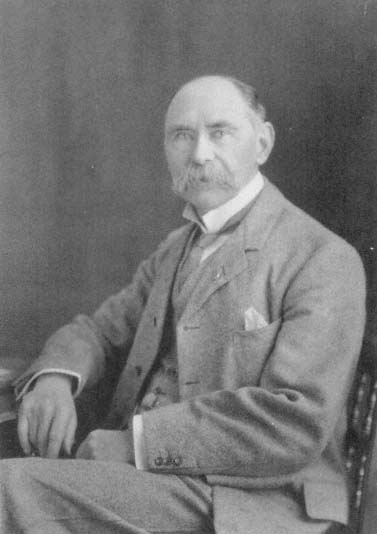

Douglas Hyde, professor of Modern Irish, University

College, Dublin. (Courtesy Sealy collection)

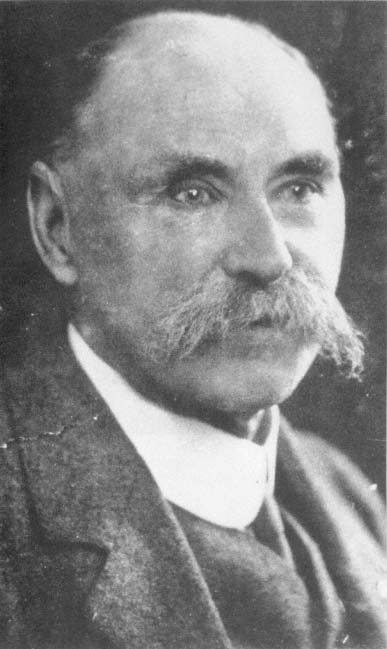

Senator Douglas Hyde, 1937. (Courtesy the Irish Press)

Postcard photo of first president of Eire, 1938, with signature on

reverse in Irish and English. (Courtesy Sealy collection)

Douglas Hyde addressing Dublin crowds in June 1938. (Courtesy the Irish Press)

Douglas Hyde with Eamon de Valera and Sinéad de

Valera, June 1938. (Courtesy the Irish Press)

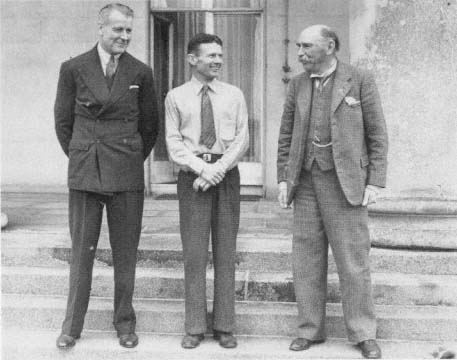

Douglas Hyde on steps of Áras an Uachtaráin with John Cudahy, American

minister to Ireland (left) and Douglas Corrigan (center), following Corrigan's

"Wrong Way" flight to Ireland in July 1938. (Courtesy Sealy collection)

President Douglas Hyde with daughter Una and grandchildren, Christopher,

Douglas, and Lucy Sealy. (Courtesy Sealy collection)

Tongue-in-cheek sketches by daughter Una Sealy: Hyde reading, Hyde "learning to play golf." (Courtesy Sealy collection)

Sean O'Sullivan drawing of Douglas Hyde, reproduced and distributed by

Irish Press, Christmas 1938. (Courtesy Sealy collection)

Douglas Hyde at work at his desk in Áras an Uachtará;in. (Courtesy Sealy collection)

Douglas Hyde with French minister, a few months after stroke in 1940. Hyde note,

back of photo, reads "I am a whited sepulchre for underneath my coat I have only

a blanket!" (Courtesy the Irish Times)

Douglas Hyde chatting with P. L. Doyle, Lord Mayor of Dublin,

July 1941. (Courtesy Sealy collection)

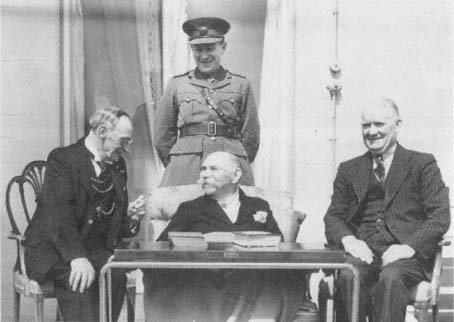

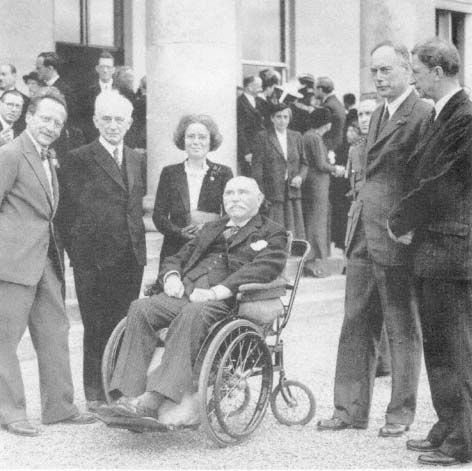

Douglas Hyde at reception marking 1943 opening of Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

With him are Erwin Schrödinger, first director (far left), Eamon de Valera, (far right), and other

scholars and dignitaries. (From the Bulletin of the Department of Foreign Affairs No.

1037 [May/June 1987]:14)

1944 portrait by Sean O'Sullivan. Confined to a wheelchair following his stroke,

Hyde sat for head and shoulders; his aide-de-camp, Eamon de Buitléar, served as

model for the standing figure—an arrangement that became a source of

amusement between them. (Courtesy Sealy collection)

Ratra, unroofed and derelict. (Courtesy the Irish Times)

Frenchpark church where the Reverend Arthur Hyde, Jr., was rector, 1867–1905,

with graves of Douglas Hyde (foreground) and other family members.

(Courtesy the Irish Times)

Schoolboys at grave of Douglas Hyde. (Courtesy the Irish Times)

to this subject." Hyde's failure to move Stanley was a bitter pill, as he was sorely in need of a coup to counter continuing threats to his position within the league and worries about the league's financial situation. It had not been an easy spring, nor did it look as if summer would bring an improvement.

Scarcely the most important yet another one of the upsetting situations Hyde had had to face in the early months of 1905 involved accusations from Father Brennan of Killarney, a member of the Coiste Gnótha, or executive committee, that stemmed from the dismissal of a reporter named Kelly from the Weekly Freeman staff. Brennan alleged that Hyde, Agnes O'Farrelly, and Edward Martyn had carried on a campaign against Kelly on account of his failure to use Connacht Irish in his Irish-language columns and had succeeded finally in getting him fired. Stung by what he called "this horrid insinuation against my personal honor," Hyde repeatedly denied the charges against himself as well as O'Farrelly and Martyn, to no avail. Brennan persisted, creating tension at a time when Hyde could least spare the hours or energy to cope with it.

Then in early May there was another flare-up in Dublin in a continuing dispute over the right of owners to paint their names in Irish on their carts. Like the mail-in-Irish campaign, the crusade of the cart owners was a cause that all Hyde's instincts told him to avoid. When someone in the league had suggested that the statute prohibiting such signs should be challenged, Hyde specifically had ordered that the matter not become an issue for the law courts. To Hyde's dismay, Patrick Pearse, whom he regarded as a close friend and protégé, had ignored Hyde's pronouncement and had himself gone to court to plead on behalf of the "cart martyrs," providing the Weekly Freeman, which reported the May 19 trial, with ample material for a dramatic profile of the passionate young barrister. What was worse, Pearse lost the case, assuring a future escalation in demonstrations, charges, and trials, and the Weekly Freeman profile of Pearse was added to the files in Dublin Castle. Additional clippings were generated in May, when the Cork Examiner reported rumors of "revolutionary tendencies . . . in certain districts" in connection with league activities. There were rumors that the chief secretary had ordered the county inspectors of the Royal Irish Constabulary to keep a careful eye on branches in their districts.

Meanwhile another source of dissension came from Protestant members of the league, many of them Hyde's closest friends and earliest supporters, who had begun complaining of bias in the organization—

evident, they said, in attitudes toward the Craobh na gCuig Cuigi, or "branch of the five provinces," which some leaguers had dubbed the "branch of the five protestants," since it was this branch that most Protestants joined. Far worse was the news, as the spring of 1905 became summer and figures from Dublin showed the league barely able to meet its monthly expenses, that the depleted treasury might present Hyde with no choice but to reduce the corps of league organizers and teachers—a serious blow, as the league's next major objective, the founding of a new university in Ireland, stood little chance of achievement unless substantial funds materialized. At the very moment of swelling grass-roots interest in looked as if the work of the league might have to come to a halt unless a source of substantial new funding could be found. But the most difficult of Hyde's problems as summer became fall required decisions that affected his personal life and an embarrassing situation that involved John Quinn.

In December 1903, with the first indications that a threatening financial crisis could stall the league's progress, Hyde had sent out urgent cries for help to friends and affiliate organizations abroad. One of his appeals had been addressed to John Quinn. In the treasury, he had told Quinn, there were but two hundred pounds to carry the organization until March. Two thousand dollars voted for league support nearly two years before by the Ancient Order of Hibernians had never been sent; he had asked repeatedly when the league might expect this needed contribution, but the AOH president kept putting him off. Quinn responded at once with a $100 donation which, as it was lost in the mail, generated a continuing exchange of letters. In one of these Quinn suggested to Hyde that they meet during Quinn's next trip to Ireland and discuss the possibility of an American fund-raising tour. "Yeats has no doubt told you of his trip here and how badly you are needed to organize the country on behalf of the League," he wrote. Hyde and Quinn met in Dublin in October 1904. Quinn presented his plan, assured Hyde of success, and—extending his personal guarantee against any possibility that the tour could result in Hyde's personal loss—promised to organize the details.

Meanwhile, as soon as the Congested Districts Board had taken over the tenanted land of Frenchpark (which of course included Ratra), Lucy had begun to urge Douglas to sell their lease and move to Cork or Dublin. She was still a clever woman with a good business sense. She did not share Charles Owen O'Conor Don's commitment to preservation of local control or concern for the future of Ireland's agricultural

economy; she did not have Douglas's sentimental attachment to Ratra. It was said that those who were selling to the CDB were getting prices well above market value. As for the prospect of a trip to America, it was not at all attractive to her. On the contrary, skeptical of John Quinn's assurances of success and anxious about leaving her daughters for eight months, she was adamantly opposed to it. For one thing, she worried what her role would be when Douglas was lionized and feted across a country that many English and Irish travelers of her acquaintance regarded as in large part a primitive wilderness. For another, she suspected Quinn (a handsome, wealthy bachelor ten years her husband's junior) of being something of a ladies' man; she had heard much whispering about the freedom of American women; and she remembered that there had been a "Fräulein" in Fredericton with whom Douglas had had something of a romantic attachment. Her opposition to the American tour became an obsession when in the spring Douglas received word that there was to be a vacancy in the university at Cork. Her disappointment at her husband's previous failures to win a university post had been as keen as his own. If he let this opportunity pass, there might never be another. Moreover, with a university position he could gracefully resign his presidency of the Gaelic League, which to her mind had brought him nothing but anxiety, infelicitous associations, and the disapproval of the kind of society that was their proper sphere.

Hyde could not really reassure Lucy on the matter of the American tour, as he himself was having reservations about it—mostly because of the possible university position, but also because he still had many correspondents in America, and from them and others he had been hearing disconcerting stories of feuds and animosities both within and between Irish-American groups. What would become of his lecture tour if, right at the start, in New York, he inadvertently offended an influential group with national connections or if anywhere in the country he was caught between competing societies? He wished he could discuss his concerns with Quinn, but how could he, when Quinn's letters were filled with enthusiastic reports of ever-increasing bookings and predictions of success? In February he thanked Quinn for a gift of rye whiskey and assured him that Lucy was looking forward to escaping the Irish winter. As for himself, he said that he had been doing what he could to spread the word of his upcoming tour: from the Reverend Peter Yorke of San Francisco he had received assurances that invitations from the universities in California would be forthcoming. He did not know

quite how to say that at the same time his old Trinity friends, Stockley and Windle, were urging him to apply for the vacant chair in English literature at Queens College, Cork—or that he had solicited letters of recommendation from Stopford Brooke and others to support his application.

On March 31, in response to repeated requests, Hyde wrote to Quinn from England, enclosing, along with a letter describing large turnouts at successful meetings, a list of his books and other major publications and titles for the lectures he might give at American colleges. For himself he wrote a memorandum with the mocking title, "Self-Laudatory," in which he set down what he considered to be his outstanding achievements, beginning "I was without doubt the first person into whose head it ever came to deanglicise Ireland, or gave utterance to this idea. The Gaelic League is practically built upon my lecture to that effect in 1892." He continued: he was, he said, the first person to write a book in modern Irish; the first to collect folklore in Irish; the first to "collect the poetry of the people from their own mouths"; the first "to write a play in Irish and act in it myself"; the first to write a literary history of Ireland; the first to address a mass meeting in Irish; the first to ask the Irish to keep speaking Irish to their children, "in New York before ever the Gaelic League was started"; the first to say go to "the poor people, the Macs and O's and the priests, and if they are for letting the language die—then let it and be damned to them."

In a letter of April 30 Hyde revised his lecture topics on the advice of Seamas MacManus ("who knows the ropes," he assured Quinn). Formerly a Donegal schoolteacher, Hyde explained, MacManus had gone to the United States in 1899 and had found there a receptive audience for the stories he told of his own parish. Hyde also advised Quinn that Tomás Bán Ó Concannon (Thomas Concannon), a native speaker of Irish from the Aran Islands and a league organizer in Connacht, would accompany him as he toured rather than go on ahead as an advance man as Quinn had suggested, as he felt that in this way he might help Hyde "make a bigger impression." Concannon "wants to use glamour. What do you think of this?" wrote Hyde, obviously amused at the idea. Quinn's answer had he given it might not have been flattering. An advance man was needed, and if Hyde did not have glamour enough on his own, it was unlikely that Concannon would be able to help him. Quinn did not like amateurs interfering with his careful planning. For months he had been devoting two to six hours daily to the organi-

zation of Hyde's tour. His New York apartment had become an office for the project, with a special secretary hired to handle the heavy correspondence.

On June 22 Hyde cabled Quinn that the American trip was off. In the letter that followed he explained that he could not go because the Cork position would begin in October. "This is too good an offer to let go," he apologized, suggesting that instead he might be able to make a short trip in the spring of 1906, appearing only at events arranged by Irish-American groups and excluding the university lectures. He concluded plaintively, "Will you ever forgive me?" On June 28 he wrote again. The Cork position was in fact not yet assured, his letter implied, but still might be. However, his responsibilities as president of the league were overwhelming him: "My last post brought me five different requests to go to programs in various parts of the country." He also confessed his fear of being caught in the notorious power struggles of quarreling Irish-American organizations. He described conflicting statements in letters he had received from America. He had been visited at Ratra by the secretary of the New York Gaelic League who had impressed him favorably but against whom he had since received written warnings. He had canceled the tour, however, primarily on account of Lucy: "My wife's delight knows no bounds at escaping the American journey and I really think she could not have borne it. She had almost got into a state of nervous collapse thinking of it and she would not let me go by myself."

Quinn could not have been less than mystified and distressed by this curious and continuing sequence of contradictory letters so uncharacteristic of the man he thought he knew and of whom he had spoken highly to such people as Martin J. Keogh, an eminent jurist with cultivated tastes and a broad knowledge of history and literature whom Quinn had invited to chair the committee appointed to serve as Hyde's official hosts. He also had been placed in a difficult position, for months of work that had gone into scheduling lectures and rallies in over fifty cities now had to be unraveled.

On July 7 Quinn received still another letter from Hyde. Having at first indicated that he had been offered the Cork appointment, and then altered that statement to say that he was being seriously considered for it, he now wrote that in fact he had decided not to apply for it but would accept it if it was offered to him! As for withdrawing from the American tour, he blamed that decision on a crisis involving Ratra.

If he did not buy it, he would be evicted by the Congested Districts Board; he did not want to give it up but Lucy hated it and was "most anxious . . . to leave."

Obviously torn by aspects of his situation he had not revealed to Quinn, Hyde turned to Lady Gregory. In a private letter he confessed that he needed to find his way out of a "muddle." She knew something of the reasons why he was close to being overwhelmed by problems and responsibilities: she had heard that the Reverend Arthur Hyde had been failing; she assumed that as usual Lucy was not happy or not well; she knew of the internal dissension within the league, its shrinking treasury, and its problems with the Post Office; she had seen newspaper reports that the league was now under Castle surveillance; she suspected that there was more. Nor had Hyde's feelings of panic been improved by the fact that every day he was receiving a stream of reports from Pádraig O'Daly, Nellie O'Brien, and Agnes O'Farrelly—loyal members of his inner guard—about the league's latest internal controversies. Whatever transpired to change Hyde's mind has not been recorded, but on July 19, in an unexplained reversal as astonishing as his abrupt cancellation on June 22, he cabled Quinn that he was "available after all for November." In the letter that followed he explained that he had settled the Ratra matter and had persuaded himself that "preaching" to American universities would raise the prestige of the Gaelic League.

Some ten to twelve days later a smiling Hyde stepped off the train in Foynes to which he had come to attend the annual Shannon feis . There to greet him were friends who, like himself, were nationalists of Ascendancy stock. Most had learned their Irish from O'Growney's Simple Lessons . Among them were Alice Stopford Green, whose historical research had lately focused on Irish topics (only recently Hyde had written to her complaining of the difficulty he had been having finishing his lectures for America); Sir Horace Plunkett, son of Lord Dunsany, like the poet AE a pioneer in the Irish agricultural cooperative movement; Sir Roger Casement, who had just established, with Hyde's support, an Irish language school at Tawin Island near Galway; Lord Monteagle and his daughter, Mary Spring-Rice (she now called herself Máire Spring Rís); and Mary Elizabeth Massey of Killakee House, Rathfarnham, described by Desmond Macnamara as so "handsome fair-haired, beguiling and by inference, attractive and demanding" that she encountered no difficulty in spreading Irish culture among the Ascendancy by introducing Irish dancing at hunt balls and house parties.

Exactly how long Hyde may have known Mary Elizabeth Massey is not certain, but it appears that they had met some time before 1903, for on February 21 of that year, at the Dublin performance of Yeats's "The Pot of Broth," he had inscribed on her program a verse in Irish that plays on the first four lines of a sensuous lyric entitled "An Chúilfhionn" (The fair maiden), which Hyde had published in Love Songs of Connacht . Others had made less personal signed and unsigned contributions to the same program: Yeats, a couplet; Lady Gregory, a flourishing signature; F. A. Longworth, an eight-line verse on dancing; a reference to a jig class; some lines in Arabic; some sketches. Hyde's prose translation of the verse published in Love Songs reads:

Mist of honey on day of frost over dark woods of oak, And love without concealment I have for thee, O fair skin of the white breasts. Thy form slender, thy mouth thin, and thy cooleen [tresses] twisted smooth. And O first love, forsake me not, and sure thou hast increased my disease.

On Mary Elizabeth Massey's program Hyde had altered the lines of the Irish verse. Translated, they read:

Mist of honey on day of frost over dark woods of oak, And love without concealment I have for thee, that I may see you again, your bright eyes, your slender form, O fair skin of the white breasts, and your blue dress, a dark mist on me, O young woman of the yellow hair.

Unsigned but unmistakably in his own hand on another part of the same sheet Hyde had provided what Desmond Macnamara describes as a "somewhat bowdlerised and sentimentalised" translation:

Like a honey mist on a day of frost o'er a grey wood of Desire of thee in the heart of me at thy gay mood woke, frock of blue, pointed shoe, and laughing rogue face. Have you found my heart, bound my heart, and left grief in its place?

Two years later at the Shannon feis of 1905 Hyde wrote in Mary Elizabeth Massey's autograph book an untranslated signed sequel to the 1903 lines. Beginning with a near repetition of the fourth line of the 1903 verse, it evokes the dark mist of the blue dress; continues with a description of the blue dress fluttering behind and around her; and ends with a lament that were it not for the worldly cares that have left him disheartened he would follow her to the ends of the earth. Gossip continued to link their names sporadically for some time thereafter.

At the beginning of August the Reverend Arthur Hyde, a semiinvalid for much of the time, began to fail noticeably. Dr. O'Farrell was

called. He diagnosed the elderly man's problem as "the natural complications of old age" and left some powders. Had the patient known, he probably would have rejected the powders. In his Kilmactranny years the rector had been a serious student of folk medicine, particularly herbal cures. Folk medicine and the classics had been his favorite subjects of study. Above his bed, like dominoes in the dust, were his Latin and Greek grammars, Lucian, Livy, and Horace. Some stood upright, some leaned against others, some were laid flat. Among his books and papers was the induction oath administered to him by his bishop in 1867: "to take real, actual and corporeal possession of the one rectory of Tibohine in the Diocese of Elphin together with all singular tythes, glebes, profits and appurtenances to the said and one rectory"; "to teach and instruct, or cause to be taught and instructed in the English Tongue . . . the children of said rectory." The oath's emphasis on rent and profits and its charge that the children be instructed in the "English Tongue" had always troubled Douglas. Still, Douglas's criticism of the church had focused primarily on his father's interpretation of doctrinal matters and beliefs, not on the church itself, which he continued to attend.

Douglas reached up and removed from the shelf his father's Commentary on the first twenty psalms, written in October 1851. On its verso pages were the prescribed Church of Ireland daily morning and evening prayers. Its binding disintegrating, its pages discolored, the home-made prayerbook was filled with the stern and self-righteous marginal glosses the Reverend Arthur Hyde, Jr., had thundered at his flock over the years. Alongside Psalm 4 the rector had written: "Do not the great bulk of mankind go astray as soon as they are born, speaking lies so that amongst domestics in families one seldom finds one whose honest lips will speak the simple truth upon every occasion?" Douglas had read and reread this passage written by his father in 1851. Did it help explain the "novae ancillae, " the maids who had barely been taken on before they fell under his father's suspicion? From verses in Psalm 12 that condemn those who beg instead of work and score flatterers and deceivers, the Reverend Hyde had found corroboration for his view of the Irish tenantry and had written in a marginal note, "This part of David's description is painfully like the lower order of Irish Romanists."

His father stirred and Douglas heard his harsh breathing over the sound of Annette's approaching steps. Annette had married Douglas's old friend Cambreth Kane in 1902, but as she and Cam lived in the Frenchpark glebe house, sister and brother still saw much of each other.

They sometimes took tea at their father's bedside. Douglas rose and replaced his father's prayerbook on the shelf with a glance at its last page, "The Office for the Burial of the Dead."

The obituary in the Weekly Freeman was succinct: It noted that both the Reverend Arthur Hyde, Jr., and his father before him had been Protestant rectors, that An Craoibhin himself had earned a bachelor of divinity in Trinity College, and that he had won in fact a theological exhibition before "Irish Ireland had claimed him" for its own.

On August 11 Hyde wrote again to remind Quinn that he wanted Concannon to be with him during the American tour. Describing the Aran Islander as "a born diplomat," Hyde assured Quinn that Concannon's "transparent honesty and simplicity" would win over everyone. Nothing more was said about either Hyde's own erratic behavior during the summer or Lucy's state of mind. Hyde was busy with his usual tasks as president of the league. He set up with Agnes O'Farrelly, Nellie O'Brien, Pádraig O'Daly, and Stephen Barrett procedures that would enable them to carry on in his absence. He wrote and revised his lectures for the American tour and completed work on Religious Songs of Connacht, scheduled for publication in 1906.

During this same month, after a period of printing mostly innuendoes, the newspapers again began carrying items concerning government surveillance of the league, its president, and some of its members. The Irish News reported that the Royal Irish Constabulary, the police force for all Ireland outside the Dublin metropolitan area, had been given instructions to look into the question of whether the Gaelic League was the peaceful educational organization that it professed to be or "a revolutionary party, meditating the overthrow of English supremacy in Ireland." In September the Church of Ireland Gazette attacked both Hyde and the league for activities inimical to the interests of Irish Protestants. Nellie O'Brien leaped to the defense with a strong rebuttal in a long letter to the Gazette printed on September 29: "We have no secrets in the Gaelic League," she declared, "whatever those may say who look on it as a dark and dangerous conspiracy." Stephen Gwynn proposed a public meeting on the topic, "Protestant Attitudes Toward the Gaelic League" to get all the accusations and counteraccusations out in the open once and for all. Patrick Pearse, Joseph Lloyd, O'Neill Russell, Stephen Gwynn, Nellie O'Brien, and Agnes O'Farrelly were among those who came prepared to speak. Hyde chaired the meeting, held in October. When it was over, Joseph Lloyd approached him again with the complaints and threats that had been marring their re-

lationship for some time. He was a founder of the league, he insisted (he had been present at the second meeting of 1893, at which time he had been named honorary treasurer), and he was being mistreated by the Coiste Gnótha. If Hyde could not put an end to the mistreatment, he would quit and emigrate to Manitoba. Hyde began to look forward to his American tour. It would be good, he acknowledged to himself, to get away for a while.

Hyde's last messages, including a hurried note to Roger Casement, had been sent off; Lucy had reviewed last-minute instructions with housekeeper, nurse, and maid. On November 5, scarcely two months after the Reverend Arthur Hyde, Jr., had been buried in the graveyard of the Portahard Church where he had been rector for thirty-eight years, Douglas and Lucy exchanged tearful farewells with Una, Nuala, and nurse Jane. As the carriage passed through Ratra's gate and along the eight miles to Ballaghaderreen, Connollys, Lavins, Mahons, Morrisroes, and Dockrys (Hyde was pleased that the families of his old Frenchpark neighbors were staying on the land) raised their hands and caps and shouted messages of good health and good luck. There was a low mist over cropland and bogs; the previous night had been chilly. In town the brougham passed St. Nathy's, the neo–Gothic Revival Catholic cathedral whose spire was visible from Ratra. It continued past Dillon's shop to the railroad station where a crowd of Gaelic leaguers from Mayo and Roscommon joined students from St. Nathy's College to send up a shout as the carriage came into view. Hyde waved to the young men and women he had coached in the spring of 1903 in response to their request for help in staging two of his Irish plays, The Marriage and The Lost Saint . There was scarcely time for the recitation of a poem in Irish to wish him success in America and for Hyde's response when, amid a round of cheers, the train pulled out.