ONE

TAKING UP THE LAND

1

Tradition as Determinant

New England folk planning, the weight of English custom, resistance to change

The Giant Cities of our country have always seemed to me, as they have to most Americans, vast incomprehensible places in which I could at most know a few people, my own block or suburb, my shopping center, and my commuting paths. I have lived with a pervasive sense of existing as a dweller in small clearings in the midst of an urban wilderness. Only the rich and powerful escape this sensation because their well-protected institutions and cosmopolitan style enable them to pretend that they are not part of the same world the rest of America lives in. All my professional career has been spent trying to understand these giant urban wildernesses by seeking the historical background to their problems—problems which flooded in toward me from newspapers and television and from just walking and riding around the cities I had settled in.

Over the years of this study I have become more and more convinced that a long tradition has accounted for the endless failures of Americans to build and maintain humane cities. Unlike many, I don't believe there ever was a good old days, a flowering of New York or Boston. Rather, like neurotic middle-aged patients, our cities are case histories of the repercussions of basic flaws and conflicts. This conviction came from many sources: from the study of patterns of suburban growth in Boston, from examining the conditions of working-class life at the turn of the century, from a survey of the long history of Philadel-

phia, the nation's first big industrial city, and from a review of current planning problems. And my ordinary citizen's life contributed to this point of view. A brief term as an editor of a weekly newspaper in an industrial and residential satellite town and my dabbling in municipal reform politics carried me into the midst of the conflicts of a giant state university. Here, in seeking to aid blacks gain admission and staff positions, helping in antiwar campaigns and drives to end secret military research, and finally in confronting the ultimate contradictions of a closed and self-serving public university seeking to resist open-enrollment demands, my citizen's life and my urban research converged.

From this experience I have made the discovery that Americans have no urban history. They live in one of the world's most urbanized countries as if it were a wilderness in both time and space. Beyond some civic and ethnic myths and a few family and neighborhood memories, Americans are not conscious that they have a past and that by their actions they participate in making their future. As they tackle today's problems, either with good will or anger, they have no sense of where cities came from, how they grew, or even what direction the large forces of history are taking them. Whether one speaks to an official in Washington or to a neighborhood action group, the same blindness prevails. Without a sense of history, they hammer against today's crises without any means to choose their targets to fit the trends which they must confront, work with, or avoid.

Thus, the basic purpose of this book is to gather together what is now known about cities and to cast that knowledge in the form of a series of present-oriented historical essays which will give the reader a framework for understanding the giant and confusing urban world he must cope with. A great deal has been learned since Lewis Mumford published his excellent The Culture of Cities in 1938, and it is time once again to portray the logic of our urban past.

Put another way, the goal of this book is to attempt to use history to replace the diffuse fears and sporadic panics which now characterize the popular perceptions of our cities with a systematic way of looking at our present urban condition. The hope is that by presenting people with their history, panic can give way to understanding, and that by bringing out what is now known about how our huge urban system performs, people can choose for themselves intelligently what needs to be done and what can be done to build humane cities in America.

There are many ways to judge cities, but for anyone who is trying to

bring the lessons of the historical past upon present problems the most useful way is to hold the city up to the measure of three traditional goals: open competition, community, and innovation. These standards are not arbitrary; they constitute the cherished ideals of our society. The goal of open competition is that in a successful city every resident should have a fair chance to compete for society's wealth and prizes. It is a goal compounded in the early years of the Republic from popular enthusiasm for egalitarian politics and laissez-faire capitalism. The second goal, community, holds that a successful city should encompass a safe, healthy, decent environment in which every man participates as a citizen, regardless of personal wealth or poverty, success or failure. This goal is again a blend in which political egalitarianism and nineteenth-century humanitarianism merged. The third goal, innovation, is directed to the principle that a city should be a place of wide personal freedom; that the variety and individuality of citizens should find expression in new ideas, new art, new tools and products, new manners and morals. This goal is a restatement of the cherished American ideal of progress. Today, after half a century of almost continuous war and unabated human suffering, the reality of progress is deeply compromised, but as a society we have passed so far beyond the modes of living by tradition that our cities will henceforth be forced to maintain their existence through innovation.

These three goals are by no means a harmonious triad; they conflict at many points. In the past as in the present, our cities have favored innovation and competition at the expense of community. New products and methods of production, new transportation, new ways of doing business have been introduced without regard for the dislocation and suffering they create. Skills have been wiped out, whole industries rendered obsolete, millions driven off the land or harried from one city to another. Competition for jobs, wealth, and power has been severe and even lethal, never completely open and fair. Blacks, women, immigrants, children, and old people have always been at a disadvantage. The inherent nature of our capitalistic system has bestowed differential and cumulative rewards so that the successful exercise a disproportionate control over the city and the lives of its residents. Consequently the strong prey on the weak, and to him that has shall be given. Today's state, serving the white middle class, is only the most recent manifestation of social and economic competition.

Although the mainstream Of our history has favored certain aspects of innovation and open competition, the goal of community has always

been an important and not always benign force. Political bosses, armed with the language of equality and the techniques of particularism, men like James Michael Curley in Boston or Richard Daley in Chicago, have closed competition and blocked the modernization of their cities for years at a time; unions of skilled workers and professionals have frequently refused to meet the needs of the public and have closed their doors against newcomers. Grassroots citizen groups have used their solidarity to exclude the blacks and the poor from their jurisdictions—both by law and by violence—or have fought off, delayed, or distorted the logical location of rail lines and highways, as well as civic improvements of all kinds.

Innovation uproots people. The sheer volume of the constant movement of Americans levies a terrible toll on the stability of our families, neighborhoods, and cities. Competition has never been fair and open; throughout our history businessmen, workers, and communities have sought to restrict it in their sector of interest or to manipulate it for their particular advantage. Community is often the enemy of innovation and equitable competition. These conflicts, the inevitable tensions engendered by such goals, can never be avoided.

Nevertheless we can choose how and where these conflicts will occur. Through democratic planning we can prescribe the self-conscious social choice of where and how the conflicts of the city are to be expressed, how the costs will be borne, how the profits reaped. Shall we stress competition or community or innovation in our schools, factories, and offices? What should the neighborhood demand of the highway engineer? Should the bohemian areas of our cities be enlarged? Should not projects for racial equality override all other claims for political power? If General Motors were to be nationalized, would its factory communities be more or less protected against corporate exploitation? Should doctors, professors, and army officers continue to be paid more than nurses, schoolteachers, and carpenters? Should new housing continue to be segregated by income level, or should the classes be mixed residentially?

Such questions are the questions of planning. A decision consciously arrived at can point out the policy to be adopted. Alternatively, questions can be sidestepped and common practice left to the workings of the marketplace and the outcome of the political power structure in the city. Whether by planning or inertia, at any given moment each city will be favoring certain aspects of our three goals over others. The success of

our cities may of course be judged subjectively by the degree to which urban patterns conform to one's personal evaluation of the goals. There is no final answer, no ultimate master plan, but there are and have been very different cities from those in which we now live. The size of our cities, the weight of the physical plant, the drag of law and custom, the obstructive interests of bureaucracies seem to restrict us to the narrowest of choices. Yet if history shows anything, it shows that American cities have been changing at a rate so rapid that in the course of one or two decades we do have enough choices to be able to plan for a balance among the three goals and to plan for balances quite different from those we now confront.

This book, then, hopes to survey the basic historical sequences that have shaped today's cities: the destruction of folk planning (Chapter 1); our tradition of land management (Chapter 2); our unfolding national economy with its accompanying internal structure of cities (Chapters 3, 4, and 5); our immigration and migration that formed a national urban culture and defined the class, racial, and religious subcultures upon which local politics play (Chapter 6). After this view of the controlling hand of the past, we will turn to a review of early efforts to rationalize the American city (Chapters 7 and 8). This study of past programs will focus particularly on the goal of community and on projects undertaken to make the community a safe and decent environment. It will also examine the historical concerns of health and housing to demonstrate how our tradition defines the present city. The history will conclude (Chapter 9) with an assessment of the choices and constraints surrounding today's urban problems.

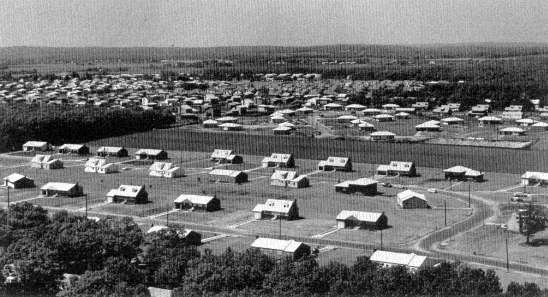

Concern for the basic needs of human society, a concern often lost in the private opportunities and shifting complexities of our developing cities, may be illustrated by a brief introductory look at the New England town of the seventeenth century, the most completely planned of any American settlement. The Puritans dealt with the same basic issues and components, but they handled them in a way unique to folk planning. Puritan folk planning flourished along the Atlantic coast from Maine to Long Island a century before what is now the United States had a town large enough to be defined as a city. For a generation or two, medieval English village traditions fused with religious ideology to create a consensus concerning the religious, social, economic, and political framework for a good life. Each of the several hundred villages repeated a basic pattern. No royal statute, no master plan, no strong

legislative controls, no central administrative officers, no sheriffs or justices of the peace, no synods of prelates, none of the apparatus typical of government then or now was required to draft or execute these plans. The country folk of New England did not need guidance, subsidies, or constraints upon the management of their property, grants-in-aid for public works or unemployment relief, or assistance for the injured or old. Rather they carried in their heads the specifications for a good life and a decent community, and for a time they were able to realize them.

But after two or three generations, the consensus crumbled and with it the replication of the towns. The culture proved inherently unstable, and the neglect of the time element in town planning and social ideals wrecked the township system. Only one feature of the seventeenth-century experience has descended to us. The Puritan form of private landholding survives as the dominant land tenure in our real-property law. In contrast to our modern planning goals, the Puritans sought a community where order and stability would enable all men to live according to a Biblical morality of love and virtue. The Puritans saw themselves as establishing a timeless system. The relationships among men, the laws and customs of the village, the pursuit of agriculture and the trades, the reading of the Bible and the gathering of the congregation to hear the preaching of the ministry—all these, they thought, would permanently maintain their earthly segment of a divine universe.[1]

The planning problem of the Puritans was to harness the land hunger of seventeenth-century Englishmen to the task of establishing a stable community where frontiersmen might live and worship. The planning solution was to identify the family as the basic unit of labor and production and the core element in social organization, and the town as the unit of settlement. The town was to be nearly self-sufficient economically, to exist by corporate self-government and corporate allocation of land, and to nourish a congregational church. The two hundred-odd Puritan towns had at their inception a group of families, with or without a minister, who had applied to the colonial legislature for township grants. In Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Maine, towns were initially founded by squatting on land purchased from the Indians, but later these settlements sought and received confirmation of their township and individual land titles. In the typical Massachusetts case the

[1] . Kenneth A. Lockridge, A New England Town, the First Hundred Years, Dedham, Massachusetts, 1636-1736 , New York, 1970, pp. 50-56.

legislature offered previously surveyed wilderness tracts or granted a license to survey and locate a township. The conditions of such grants were two: the town planters had to occupy the sites, erect houses, and create a going community within two or three years; and they had to be numerous and prosperous enough to support a minister and a church. In some cases the founders failed and the legislature intervened, revoked the grant, and took a direct hand in supervising the development of the struggling village.[2] Such conditions were unlike those in most of the colonies and unlike those during most of the subsequent history of the United States, in that land grants were contingent upon an intent to settle and to build a community. The more usual American style was to seek out land for future speculation, to settle as individual families instead of in village groups, and to allow villages and towns to rise or not, depending upon the natural course of commerce and real-estate promotion.

Following the grant of a Puritan township—free except for surveying costs and sometimes a purchase payment to the Indians—the founding families declared themselves a permanent community by signing a covenant.[3] The covenant essentially said that each signatory (and his family and heirs) agreed to be bound by the laws and to accept the taxes, duties, and obligations of the town. At this beginning moment the covenanted corporation held title to all the land of the township, many square miles of wilderness. The church, although supported by township taxes, was a separate entity, governed by the more limited membership of those Puritans who had undergone conversion, but attendance and possibility of membership was open to all the men, women, and children of the town.[4]

The mode of allocating town land assured the early achievement of the community and religious goals. The land resources were immense by English standards, thirty to a hundred square miles of raw land, but the founding families were not allowed to scatter or to homestead isolated family farms. Neither was a Bible communism to arise from community

[2] . William Hailer, Jr., The Puritan Frontier, Town-Planting in New England Colonial Development 1630-1660 , New York, 1951, pp. 17-28, 31-42, 104-105.

[3] . Page Smith in As a City Upon a Hill, The Town in American History , New York, 1966, pp. 3-16, has tried to make the seventeenth-century Puritan settlers covenant a cultural precedent for all American towns, but the Puritan town is not the parent of the commonplace nineteenth-century small town. It descends instead from the settlement habits of New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia.

[4] . Lockridge, New England Town , pp. 23-36.

property and community labor. Legally the town moved to set up individually owned and worked family parcels, but by manipulating the placement of these parcels it sought to bind independent families into the social unity of an English village.[5]

Upon completion of the survey of the future village, each family was immediately granted a home lot. On this lot the husbandman was to erect his house and barns, set his fruit trees and garden, and tend his family stock of milch cows, oxen, sheep, and poultry. These home lots, which varied from as little as half an acre for a poor bachelor to as much as twenty acres for a wealthy family, were laid out against one or two streets that adjoined a strip of fenced common land where cattle could be penned and the future church erected. The first church was a modest affair, but in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries the townsmen built the large white Christopher Wren churches which established the modern standard "colonial" church for American Protestantism. Also, these later generations drove the cattle off the commons, refencing and landscaping the rough village space and thereby transforming it into the town greens which have been the envy of most suburban subdivisions ever since.[6] Home-lot grants varied according to a number of factors. The size of a man's family counted; men with many children received larger than normal allocations, bachelors small lots. The community's need for a man's services counted; millers, blacksmiths, and ministers were attracted by offering double and triple allocations. Finally, because as seventeenth-century Englishmen and Puritans the settlers recognized hierarchy to be the natural and desirable order of society, men of means or status were given larger allocations or subsequent land bonuses.

Despite such differentials, most families in fact received very similar parcels, and with few exceptions the largest grants were not more than eight times the smallest. In Boston the wealthy grasped much more of the town's wealth in their hands. By all later American standards these first townships were the most equitable allocations of resources the

[5] . Philip J. Greven, Jr., Four Generations: Population, Land, and Family in Colonial Andover, Massachusetts , Ithaca, 1970, pp. 50-55; Lockridge, New England Town , pp. 10-13; Sumner C. Powell, Puritan Village, the Formation of a New England Town , New York, 1965, pp. 107-108, plates 9, 10.

[6] . John W. Reps, The Making of Urban America, A History of City Planning in the United States , Princeton, 1965, pp. 124-28; Paul Zucker, Town and Square, From the Agora to the Village Green , New York, 1959, pp. 242-44.

country ever knew. A rough commonalty of property prevailed, and no one was left out. Never again was popular consensus able to forge so inclusive and equitable an economic program.[7]

Beyond the village home lots lay the farm parcels, intentionally scattered so that no family should locate on a single tract. In these years a family normally received about a hundred and twenty acres, of which only about twenty-five acres could be actively cultivated. The remainder was to be used for grazing cattle, mowing wild grasses, and cutting firewood. Wheat and rye, the major grain crops that lay at the core of this subsistence agriculture, were grown in one or two common fields in which each family was given a strip proportionate in size to its home lot, and here each farmer was to work his own allotment. In the first years, when many settlers arrived without tools or cattle, the plowing of the strips in the common field must often have been a community project. But at the core of New England farming—as of New England religion—lay individual effort and responsibility.[8]

The early towns were intended only to support a primitive economy of self-sufficient families and autonomous villages. Farming was crude and laborious, and the output of each farmer varied with his energy and that of his family. Instead of searching for specialties that might bring a higher cash return, as their eighteenth-century descendants were to do, the first generation seemed content to clear the land slowly and to strive for a stable agricultural routine. Since most of the towns were located along the coast or on a river, they relied on water transport for their infrequent dealings with the outside world. Indian footpaths, trails that wound through the forests, were the only long-distance roads in the colonies, and many towns did not build roads even to connect the villages of one township to its next neighbors. Some towns were too self-centered even to meet their obligation to send representatives to each assembly of the legislature. There were, to be sure, occasional promoters and merchants, and each town had a storekeeper who took in grain and cattle and arranged for the purchase in Boston and elsewhere of salt, cloth, iron, and other goods. The market was not, however, a primary orientation for these farmers.[9] For them, worldly wealth consisted of an

[7] . Greven, Four Generations , pp. 44-48.

[8] . Darrett B. Rutman, Husbandmen of Plymouth, Farms and Villages in the Old Colony 1620-1692 , Boston, 1967, pp. 59-61.

[9] . Anthony N. B. Garvan, Architecture and Town Planning in Colonial Connecticut , New Haven, 1951, p. 54; Rutman, Husbandmen of Plymouth , pp. 20-21.

estate in land, and this goal the township could and did guarantee to the first generations of its members.[10]

Clearly population growth, economic change, or cultural modification spelled conflict and disruption for the order and stability of the cluster of closed villages. For about two generations the ease of founding new townships when old ones were filled or split by controversy made New England a stable system of multiplying cells. The founding families welcomed newcomers to a full share of the town's land divisions until the resident community sensed that it was complete; thereafter no more home lots were granted. Such a moment sometimes came with the crowding of the wild meadow by the townsmen's cattle. More often the land-distribution rolls closed when, typically after ten to fifteen years, the first families felt that their town had enough settlers to become a viable village. Latecomers continued to arrive in the more prosperous towns, and they could and did purchase land from the founding families, but folk planning did not anticipate and made no allowance for continuous expansion.[11]

The genius of the township system, distinct from later planning ideals and achievements, lay in its crude organization of freedom and opportunity in group, not individual, terms. More strongly than in the tightest urban ethnic or racial ghetto or in the closed union or in the inbred family corporation, the unity of land control combined with a common village and religious experience to force men of the time to seek change only in group terms. The young and dissident could not break away as individuals from village constraints, since to have done so would have cost them their culture. Only to the extent that the disaffected could form themselves into new town-building groups could they gain direction over their own futures.[12]

Town division, however, could not alone cope with long-term changes. Steady, undramatic demographic and economic pressures eroded the established culture. Perhaps most surprising to the founding families was the fact that the religious consensus was the first element in

[10] . J. B. Jackson has written a beautiful summary of the orientation of the first generations, "The Westward-moving House," in Landscapes, Selected Writings of J. B. Jackson , Ervin H. Zube, ed., Amherst, 1970, pp. 10-19.

[11] . English custom, continued for a time here, sought to maintain a permanent village of a more or less fixed number of families. The method of control was the father's holding title to the property upon which his sons settled. Greven, Four Generations , pp. 75-84, 98-99.

[12] . Powell, Puritan Village , pp. 167-77.

the township culture to give way. Most of the children of the first settlers did not live the intense religious life of their parents, and the experience of conversion which informed adult life of the older generation did not so often repeat itself in the children and grandchildren. Protestantism was itself becoming an ever-shifting, ever-dividing mass of religions, and soon after the migrations of the 1630s Quakers and Baptists and lesser heretics began to appear in the towns. The loss of deep orthodox faith created in each village a dangerous ideological potential. Religious indifference or dissent lay in wait, ready to reinforce any demographic or economic change that might press in upon the old unities.[13]

Even within the oldest townships the single-nucleus village could not be maintained against demographic pressures. New villages were started within the large townships and inevitably brought with them demands for multiple congregations, conflicts over town management, religious schism, and political divisions. If, as was often the case, the old township kept its political boundaries but sheltered within it many villages and many churches, the unified cultural, religious, and social life of the Puritan village was lost there forever.

A new farm pattern also emerged as the generations went on. To preserve intact the home lots along the common, sons and grandsons were often given outer parcels of land. By such inheritance practices the old New England towns came to resemble the speculator-managed eighteenth-century farm settlements, and thus New England fell in with common American ways.[14] As the countryside advanced across the wilderness by single-family farms and crossroad store clusters, the political units—townships and counties—were woven into a fabric of low-density settlement and multiple villages. The eighteenth-century social geography matched its economy, oriented to the markets and to specialized agriculture.

The moral of the story depends, as in all historical tales, upon the eye of the beholder. For the seventeenth-century pioneers the story foretold the "ruin of New England."[15] For the eighteenth century it repre-

[13] . Richard L. Bushman, From Puritan to Yankee , Cambridge, 1967, pp. 54-82, 107-21; J. M. Bumsted, "Revivalism and Separatism in New England: The First Society of Norwich, Connecticut as a Case Study," William and Mary Quarterly , 24 (October 1967), 588-612.

[14] . Garvan, Architecture and Town Planning , pp. 61-77; Glenn T. Trewartha, "Types of Rural Settlement in Colonial America," Geographical Review , 36 (October 1946), 569-80.

[15] . William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation 1620-1647 , Samuel E. Morison, ed., New York, 1952, pp. 252-54.

sented a happy escape into prosperity and personal freedom. For the nineteenth century and today's boosters of modernization the story reveals the benign hand of progress. The history of the New England township system carries multiple meanings, but as a base for the examination of the American city surely its most pervasive theme carries the most important message: to plan without regard for the processes of change is inevitably to fail.

2

Saving Yesterday's Property

Management of land, zoning, city planning, and interstate highways

Land Law is the One Element from America's seventeenth-century heritage that has survived and flourished. This law, as brought to our shores by settlers in both Virginia and New England, has persisted ever since as the framework for a basic concern of our cities—the management of land. The pioneers can scarcely be blamed for such an anomaly, for in their time they envisioned no cities at all. The responsibility rests rather with successive generations of Americans who, by their unwillingness to move beyond the confines of private landownership, have produced today's disordered, inhumane, and restricted city. The story of the adventures that seventeenth-century law encountered in our lightly settled continent is worth telling because it documents the inevitable failures awaiting any nation that honors the vested powers of the past over the human needs of the present. In addition, the attempts of nineteenth- and twentieth-century reformers to stay within the confines of the old law, despite its obvious inability to cope with ever more severe problems, reveal the special irony of our tradition: our almost universal faith in private property as the anchor of personal freedom, and our recurrent recognition of private property's social, economic, and political tyrannies.

The genius of seventeenth-century land law and the wellspring of its subsequent support lay in its identification of land as a civil liberty instead of as a social resource. A philosopher in any age might state

without fear of contradiction that property owes its very being to the society that protects it, and that land law is nothing except the social rules whereby fights in land are transferred from the group to the individual. Yet such a statement was and still is essentially meaningless to New World landowners and land seekers. The first settlers came as land-hungry Europeans, greedy for the freedom and independence that landownership necessarily confers in an agricultural society. Even in the New England exception, where old village ways persisted for a time, private ownership of land became the avenue of escape from village and church restraints.

There can be no doubt about the vision of the firstcomers. The proprietors of the earliest settlement corporations sought the least feudal of available English modes of landholding, the Kentish tenure, and later colonists expanded the freedom of that tenure until the energy and enthusiasm of the Revolution swept away all barriers and established our modern fee-simple ownership as the common form in America. Under the Kentish rule no farmer or landowner owed feudal duties of military or other service to a king or lord in return for a fight to occupy land. By the same token the ownership of land gave no man governmental powers over others; no king, lord, or gentleman had the right to hold special manorial courts, or carry on any other judicial or governmental function merely because he owned land or controlled a village of tenants.[1] In America a man owned land and paid taxes, or rented land and paid cash or goods to the landlord, but neither as owner or tenant did anyone have the right to dictate to whom he might or might not sell his land, who might inherit his property, or whom his son or daughter might marry. Such considerations nourished the first settlers' vision of land as a civil right, a right against the long-standing obligations of a crumbling feudal society. The sheer abundance of land here and the almost unlimited possibilities for its ownership fed the fires of enthusiasm for an individualistic land law. In this popular form the faith of farmers and townsmen in land as a civil liberty meant not only freedom from the meddling of feudal lords or town officials, at least as important, it meant freedom for even the poorest farm family to win autonomy, freedom to profit from rising values in a country teeming with new settlers, and freedom to achieve the dignities and prerogatives that went with the possession of even the smallest holding. In colonial times the

[1] . Marshall D. Harris, Origin of the Land Tenure System in the United States , Ames, Iowa, 1953, pp. 37-38, 99, 191-92.

ownership of land conferred the right to vote and to be a member of the political community; today it means security, credit, and the social standing that is a protection against the harassments of police, welfare, and health officials.

A few ancient customs did endure through colonial times only to be swept away during the American Revolution. The large holdings of the Penn family in Pennsylvania, the Pepperells in Maine, the De Lanceys in New York, and other proprietors of vast royal grants were seized by the states and sold. Primogeniture was abolished. The tradition of the descent of property to the eldest son had never been popular in the colonies, where most people bequeathed their property in equal shares or followed the Biblical custom of a double share for the eldest son and equal shares to all the others. Likewise the right of the landowner to entail his property in his will—that is, to forbid its sale by his descendants—was made illegal. In all the states, constitutions and court decisions confirmed these reforms. Finally the Northwest Ordinances of 1784-87 and the new federal Constitution codified colonial custom and Revolutionary modifications so that thereafter all land west of the Alleghenies would be held and descend according to fee-simple tenure.[2]

This codification meant that most American land has ever since been free to reflect the economic market and to respond to the social and political barometer of contemporary events. No hindrance has been imposed by the existence of giant tracts of land tied up in enduring legal restrictions, except that much of it has customarily remained subject to the traditional prejudice against black ownership of land.[3] Briefly, land could be leased, bought, sold, and bequeathed with great simplicity. Three witnesses and a written document were all that was required for a binding land transaction. As for inheritance, wills again needed only a written document and three witnesses. Resident and nonresident landholders were to be taxed equally, and no tax was to be levied on federal government land. Finally, no private property was to be seized by any governmental agency except under due process of law. A man's property represented his free status, and it was not to be disturbed except for important public purposes, and only then after a full hearing and just compensation.

[2] . J. Franklin Jameson, The American Revolution Considered as a Social Movement , Princeton, 1940; Frank E. Horack, Jr., and Val Noland, Jr., Land Use Controls, Supplementary Materials on Real Property , St. Paul, 1955.

[3] . Leon F. Litwack, North of Slavery , Chicago, 1961, pp. 93, 168-70.

Thus the nation emerged from the Revolution and the formation of the Union with the freest land system anywhere in the world. As the first modern republic it quite appropriately basked in its enthusiasm for the rights and liberties of a society of small proprietors. But ugly surprises were in store: the unlooked-for consequences of the play of social and economic forces upon the ultimate scarcity of land itself.

The inability of the traditions of land law and land management to deal with land as a social resource was productive of many disorders, but a few major cases will suffice to demonstrate the seriousness of the error of viewing land only in terms of a civil liberty. In the cities of the nineteenth century the prevailing habits of mind blocked municipal building projects and doomed to short fall even modest efforts to make the environment safe. In the late nineteenth century, when the growing size of the city and the rising values of its downtown land upset all balance between local government and landowner, the law broke down. The builders of skyscrapers pushed their gigantic social and economic costs off upon the municipalities and their fellow citizens. In the suburbs thousands of small proprietors destroyed civil liberties by racial covenants and class and racial zoning. Finally city planning, that most ambitious of all attempts to adapt land tradition to modern urban needs, collapsed under the pressures of the mammoth highway projects of our own day. Despite the best efforts of generations of reformers who have attempted to work without disturbing the basic relationships of private property within our tradition of land law and land management, the American city is the inhumane place it is because we cling to the formulations of the seventeenth century and the myths of a society of small proprietors.

The failure of the public to consider land as a social resource first brought defeat to the concept of a nation of independent landowners in the agricultural areas. The relentless pressure for easy access to public lands led the federal government to adopt a system of automatic disposal of the public domain to private owners. For the first seventy years the government's land-disposal acts (and it has been estimated that one-quarter of all Congressional activity in the nineteenth century was concerned with land legislation) moved in regular progression toward cheaper prices for land and easier methods of acquisition. Until 1800 the smallest unit that could be purchased was a section of 640 acres, the price $1,280. By 1841, under the widely utilized Pre-Emption Act, 160 acres or less could be obtained merely by occupying it and paying the

government $1.25 an acre for it. By 1862, with the passage of the Homestead Act, a settler could receive 160 acres of surveyed land after five years' residence upon payment of a registration fee of $26 to $34.[4]

The consequence of this federal policy of easy, unsupervised land disposal was to deliver up the development of the West—farms, plantations, villages, towns, and cities—to private speculator control. Speculators determined much of the subsequent history of the West because they had money or had access to capital with which to cover the development costs of the new land, and to the initial investment were added the costs of clearing, sod-busting, the building of barns and houses, fences, machinery, drains, livestock, and seed. Given the unequal distribution of capital in the nation, abundant land meant, first and foremost, abundance for those with capital.

By and large, the federal government sold land at a uniform minimum price; anyone could purchase as much as he wanted. But all land was not equally valuable. Those who had private capital, or were bankers or agents for Eastern money, had an enormous advantage. Such men could purchase a whole valley, a promising townsite, whatever they wished. They could then sell part of it cheaply to settlers and retain large tracts and await the substantial price rise that would follow in the wake of the development of adjacent land. Through large-scale purchases the speculator became a central figure in the allocation of physical resources, and this role was reinforced by his further activity as local moneylender. The pioneers, whether homesteaders, squatters, or farmers who could pay cash for land, needed capital for improvements, and few of them had resources outside their farms. It was inevitable that the lending of money should give speculators a strong local control over the development of land owned by others.

The influence of these remote speculators on modern America has been substantial. In the first place, farm tenancy was introduced and extended by their hold on land disposal. Squatters customarily had to borrow money at usurious frontier interest rates to meet the purchase price of land that had been surveyed and put up for government auction, and many of them failed or slipped into tenancy at this point. Even those able to pay for the initial purchase often could not meet the additional cost of improvements and thus fell into tenancy. In short, the

[4] . Paul W. Gates, History of Public Land Law Development , Washington, 1968, pp. 33-48; Roy M. Robbins, Our Landed Heritage, The Public Domain, 1776-1936 , Princeton, 1942.

abundance of vacant land did not obviate the need for capital to develop it, and the price of much of this capital was farm tenancy.

Speculators also determined in specific ways the locations of heavy public and private capital expenditures. The history of the placing of a canal, railroad, county seat, college, or hospital is more often than not the history of competition among interested investors who hoped to acquire the overflow benefits for their own properties. For instance, promoters from Cairo, Illinois, long distorted the plans for the route of the Illinois Central Railroad in the hope of making themselves rich in land grants and town locations. Because of their perseverance it took fourteen years of pulling and hauling among local, state, and national interests before the final more rational route could be mapped out. Kansas was torn apart by groups warring for different railroad locations as much as by the issue of slavery, and Atchison is still served by three railroads as a result of the corrupt activities of a speculator named Samuel C. Pomeroy. To such wasteful practices in the field of transportation must also be attributed the impaired functioning of innumerable poorly located colleges, hospitals, and other state and federal institutions. Such are the unfortunate legacies of the large speculator and his hold on legislative chambers.[5]

Finally there was a political result from the federal land policy and its control by local speculators. This control, by concentrating landownership and allocation powers in a few hands in the small towns and cities, settled a vast class of conservative interest across the nation: it installed men who saw the duty of government to be the defense of private property in every town in North America. These men and their successors opposed the introduction of a ten-hour day in their mills, opposed Granger laws, and continue today to work against any legislation that threatens their local economic power. These rural capitalists have been partially bought off in the twentieth century with agricultural subsidies. Their urban counterparts, formerly owners and dealers in municipal government, like the small-town capitalists, are also beginning to be harnessed to the federal government. The big-city real-estate owners, insurance dealers, retail merchants, and contractors are more and more seeking and receiving aid for private business from Washington.

[5] . Paul w. Gates, "The Role of the Land Speculator in Western Development," and Allan G. Bogue and Margaret B. Bogue, "Profits and the Frontier Land Speculator," in Vernon Carstensen, ed., The Public Lands , Madison, 1963, pp. 349-94.

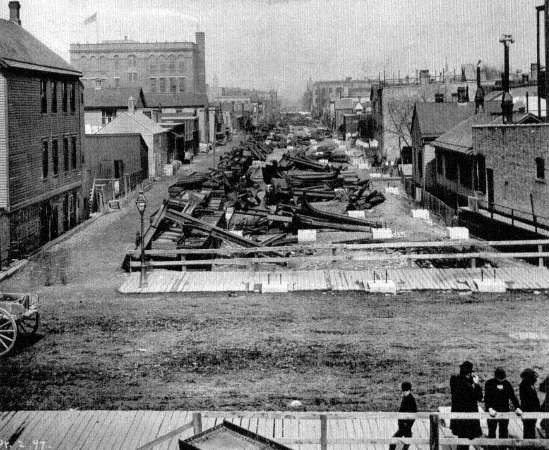

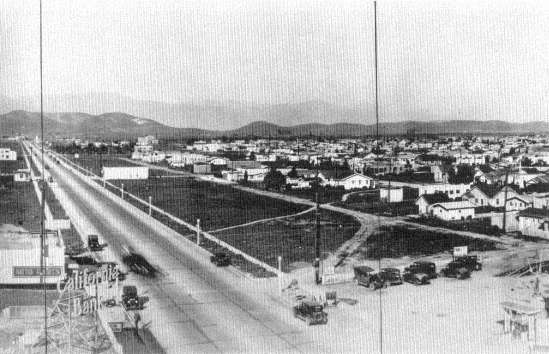

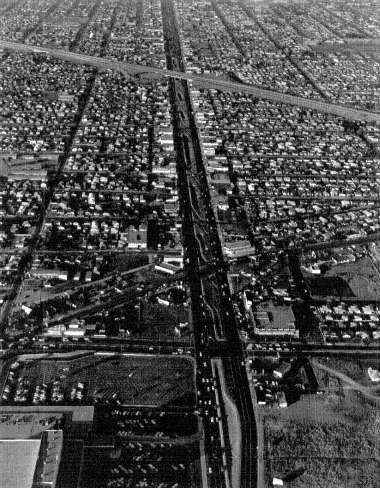

Another heritage from the federal land system of the early nineteenth century is the federal survey system that underlies the mapping of most neighborhoods west of the Alleghenies. The survey's basic element was the township, a square six miles on a side subdivided into thirty-six square sections of 640 acres each. These townships and their subdividing lines have contributed permanent features to our urban landscape.[6] Today in most parts of the nation the pedestrian or motorist moves along straight streets bordered by rows of shade trees. Ahead is a distant horizon, not a wall of buildings that gives him a sense of urban enclosure. Flanking him are rows of small buildings, usually wooden, freestanding, and set back from the street by lawns. This standard visual environment, compounded of the commonplace tradition of wooden house construction and the constraints of the rectangular survey, is our visual heritage. It is the townscape we repeat over and over on a slightly expanded scale, and with surprisingly few modifications, in the suburbs of megalopolis.

What the grid failed to do was to produce centered and bounded neighborhoods. Without parks or plazas it lacked a center; the natural center of the federal land survey became the main street, the highway strip. Although such commercial concentrations were expedient, they failed to mark town centers or subcenters, as plazas do or as the old New England town green with its meetinghouse did. In addition the open grid pattern provided no fixed boundaries for neighborhoods, no point from which city dwellers could define their own vicinity visually and socially against the endless metropolitan complex.

Within large cities the concept of land as a civil liberty brought repeated failures with highly serious and enduring consequences. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and the Constitution of the United States in its Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments both specified that no private property should be seized by any agency of the government or any corporation granted the government's rights except by proper hearing, proper compensation, and for a legitimate public purpose. The Fifth Amendment states: ". . . nor shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation." And the words of the Fourteenth Amendment are: "No State shall . . . deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." American courts

[6] . Norman J. W. Thrower, Original Survey and Land Subdivision , Chicago, 1966.

have interpreted these statements to mean that, above and beyond the private landowner's right to compensation for his property, there stands some residual right against the government, perhaps best described as a right not to be disturbed unless some public purpose requires the seizure of his property. Neither the state nor the federal government may interpose its power to seize property merely for the purpose of transferring land from one private owner to another.

In the early nineteenth century these provisions of the Fifth Amendment and the Northwest Ordinances, and similar provisions in state constitutions, caused no difficulties. Courts interpreted as "public purpose" whatever public bodies ordered. Private companies formed for the purpose of constructing turnpikes and bridges were given the state powers of eminent domain in order to assemble their rights of way. Milldams, canals, telegraph lines, projects for waterworks or gasworks, and municipal markets all went forward by virtue of the use of state or federal powers of eminent domain.

During the Jacksonian era, as public projects became larger and private corporations (especially those formed for canal and railroad projects) gained strength, the courts began to narrow the definition of public purpose, hoping thereby to limit governmental action. Railroads appeared as dangerous monopolies and showed themselves powerful enough to purchase entire legislatures. Farmers and city dwellers feared that they would lose their farms and homes to railroad rights-of-way, as people today fear the incursions of highway projects. Cities and towns and even states went into bankruptcy in the 1840s and 1850s because they had pledged public funds to private canal and railroad corporations. Large-scale municipal corruption began to be revealed, and a general bias against governmental undertakings of all sorts set in. For the next half century the powers of eminent domain were increasingly narrowed by a succession of court decisions.[7]

Thus at the very moment when municipal projects needed to be enlarged to accommodate themselves to the ever-growing American city, the courts began to restrict municipal powers over land. Boston, even after a disastrous fire in 1872, was forbidden to use city funds to aid owners of private property in an ambitious redevelopment scheme for the downtown area.

In Boston also the common law had allowed the city to seize surplus

[7] . Philip Nichols, Jr., "The Meaning of Public Use in the Law of Eminent Domain," Boston University Law Review , 20 (November 1940), 615-41.

land surrounding a public building and sell it back to private owners, on condition that they develop their private parcels in a manner harmonious with the new public one. In 1910 a conservative court forbade such condemnations, although the city had followed this identical procedure when it built its handsome Quincy Market in 1825.[8] A Pennsylvania court forbade similar practice in that state.

The municipal and state reforms of the Progressive era of the early twentieth century, however, did slowly widen judicial narrowness in this field. Between 1911 and 1933, fifteen states either amended their constitutions or enacted specific legislation to allow more generous condemnation rights so that land near public highways and buildings could be controlled as part of the projects themselves. At the same time state and federal courts relaxed the rules laid down in the previous century, but they failed to return to the full freedom of action of the earliest years of the nation.[9] The continued sway of the conservative judicial heritage has proved a grave misfortune for the American city.

During the New Deal the Federal Emergency Administrator of Public Works, in response to unemployment, instituted a number of public housing projects to make work for the building trades and to create cheap, sanitary, low-cost shelter. These were the first peacetime public housing projects ever undertaken by the federal government, indeed among the first by any American governmental agency. Many saw them as a radical departure, a long step toward European socialist methods.

At that moment a United States Circuit Court, reviving the waning doctrine of public purpose, ruled in the Louisville Lands case that the federal government could not condemn private land for low-cost housing: such undertakings exceeded the powers of the Constitution and were therefore not legitimately to be defined as public purpose.[10] One circuit judge dissented and the decision was later overruled, but the political damage had been done. Just when Congress was debating the

[8] . Walter H. Kilham, Boston After Bulfinch , Cambridge, 1964, p. 22.

[9] . For examples of judicial confusion, such as an interpretation that the Fourteenth Amendment forbade excess condemnation even though a state's constitution specifically authorized such a practice, see Cincinnati v. Vester , 33 Federal 2d 242 (1929), 281 U.S. 439 (1929); for the newer liberality, holding that a government may seize property for the benefit of a private person if the transaction is related to an important public purpose, see International Paper Co . v. United States , 282 U.S. 399 (1931).

[10] . United States v. Certain Lands in the City of Louisville , 78 Federal 2d 684 (1935).

issue of public housing and popular opinion was clearly divided, this ruling made the supporters of federal participation in the field decide to abandon direct action and to institute in its place an indirect grants-in-aid program. This modification, originally designed to soften the opposition of conservatives between 1935 and 1937, has created the structure under which all federal housing and urban renewal has gone forward ever since. As a consequence, housing and renewal efforts have been tied to the boundaries of each municipal corporation, and our national administrative powers in respect to housing have depended upon the capabilities of municipal civil servants. In the context of today's concerns, this structure has meant that until after World War II public housing was racially segregated according to each city's traditions; it means at present that public housing cannot be located in a metropolis on the basis of free choice but only in accordance with the class and racial prejudices of each municipal subdivision.[11]

Finally, the narrow interpretation of the public-purpose doctrine has contributed to an unforeseen pejorative attitude toward contemporary housing projects. The doctrine, first meant to cast judicial suspicion on all projects, persists in the superheated language concerning poverty, disease, and moral decay used to justify public land appropriations. The dissenting judge in the Louisville Lands case, trying to uphold the project under the doctrine of police and welfare powers, said, "The slum is the breeding place of disease and crime. . . . If disease and crime are to be rooted out of slum neighborhoods, the residents must be placed in houses which they can rent or buy. The wrecking of the rookeries must be followed by new and inexpensive housing." The famous New York case, New York City Housing Authority v. Muller , supporting public housing followed, and it confirmed the principle of public action on the ground of the "menace" of the slum.[12] So lawyers have been arguing ever since. To fight off the conservative attack on public projects and to guard against a return to a set of dubious nineteenth-century precedents, our courts and newspapers still reiterate "menace" and "blight." Instead of testifying to the positive need of our fellow citizens for decent homes, we feel a compulsion to frighten ourselves with the specter of cancerous social ills.

[11] . Some Southern cities have even used their municipal independence under urban-renewal and public housing grants to move blacks about in order to create single ghettos where Negro settlements were scattered through the city. Theodore I. Lowi, The End of Liberalism , New York, 1969, pp. 251-66.

[12] . New York City Housing Authority v. Muller , 270 New York 333 (1936).

The unreasonable warping of municipal and public housing programs was by no means the only legacy of the legal escalation of the dimensions of private landownership. In hundreds of ways this narrow focus prevented our cities from responding successfully to the conditions of their own growth. To put it most simply, while the American tradition of land management was concentrating on the rights of the owners of each bit of land, the city was growing into a giant system whose interactions and intercommunications spread over many miles. Despite immense public works, the stretching of old common-law concepts, the invention of zoning, and the institution of the practice of city planning, the tradition has proved unable either to meet the new need to treat land as a social resource or to defend the old reliance on land as the basis of personal freedom.

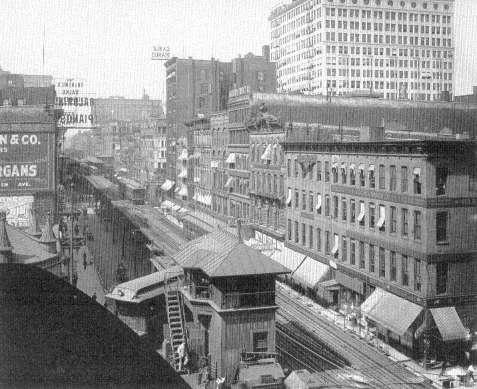

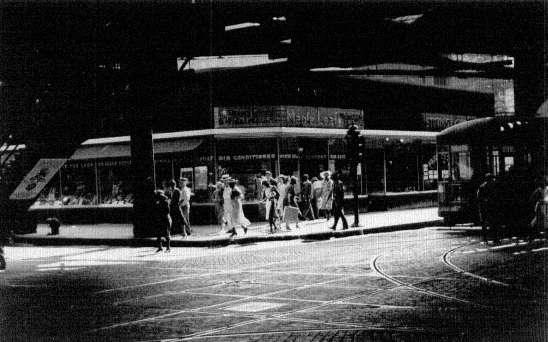

Cities attempted to resolve the conflicts between the integrity of each small plot and the growing interdependencies of the city in two ways: by establishing networks of public services in the streets to bind together individual parcels, and by expanding the regulations of private behavior outward from the old common-law base. As early as the epidemic of 1793, Philadelphia discovered that each section of personal property could not safely support a private well. That year, yellow fever killed four thousand residents, a twelfth of the population. Such plagues returned to Philadelphia and other cities for the next seventy years. Slowly, first in Philadelphia and then in Baltimore, Boston, and New York, the booming cities invested millions upon millions of dollars to construct public waterworks.[13] In their finished form these systems carried pure water through the streets parallel to the boundaries of each private lot, and the cities spent more millions to build sewers to carry off the wastes.[14] Toward the same objective—a safe and sanitary city—municipal authorities hired street-cleaning crews and instituted trash and garbage collection. In addition to this publicly financed effort, the concentrated population of the large cities made it possible for many new services to be offered for profit by municipal or private monopolies: coal gas for cooking and lighting, electricity, street railways, and elevated

[13] . Nelson M. Blake, Water for the Cities , Syracuse, 1956.

[14] . The magnitude of this sanitary effort is not commonly appreciated by historians. It can be grasped immediately by a survey of the annual reports of any city or of summaries like Charles P. Huse's The Financial History of Boston , Cambridge, 1916. Twentieth-century municipalities, however, have failed to carry on this effort with the same energy as in the past, thereby contributing to today's ecological crisis. See Solomon Fabricant, The Trend in Government Activity in the United States Since 1900 , New York, 1952, pp. 72-83.

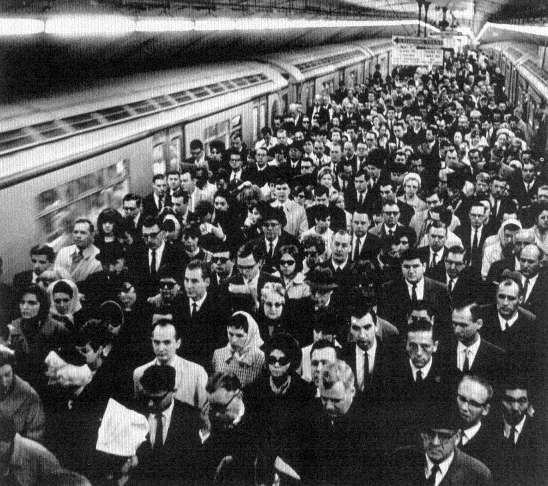

and subway systems. The regulation of these monopolies in the interest of the mass of small consumers proved exceedingly difficult and occupied a major place in the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century politics. All in all, the multiplication of public and private utilities was a major accomplishment of the nineteenth-century city and one in which contemporaries took justifiable pride.[15]

Yet the entire century, for all its accomplishments, was in fact the backdrop for a seesaw battle waged by municipal services and timid regulations against the behavior of landlords and the excessive individualism of the land law. As booming growth offered chances for profit in slum housing and sweatshops, private owners increasingly ignored or attacked the health and safety of their fellow men by intolerable crowding of streets and structures and by deliberately cutting off light and air from tenants and neighbors. Only very slowly and cautiously were the old public duties of landowners redefined to combat some of these urban conditions. The ancient prohibitions of nuisance law, such as those against noxious trades, dangerous construction, and disorderly houses, were slowly expanded to support fire, health, and building codes. These codes specified the materials and methods of construction that would make buildings slow-burning or fireproof and that walls and floors must be structurally sound. Ultimately health codes for tenements and multiple dwellings set forth the number of persons who might legally occupy a single room, the size of windows, provision of water and toilets, and so on. But enforcement of such regulations has never been popular, and there has always been much evasion of them in declining neighborhoods.[16]

The weaknesses of the nineteenth-century achievements lay in the legal moat surrounding private land. Affirmative municipal action had to stop at the margin of the street. If toilets, lights, fire barriers, windows, stairs, and central heating were to be installed, the landowner had to do it, and execution therefore was dependent upon his financial capabilities and his personal willingness to modernize. Philadelphia, as the pioneer in waterworks, was the first to discover that to bring a water pipe to the

[15] . The complementary public and private amenities of the century are discussed in James Marston Fitch, American Building , v. 1, 2nd ed., Boston, 1966, p. 108.

[16] . Joseph D. McGoldrick, Seymour Graubard, and Raymond J. Horowitz, Building Regulation in New York City , New York, 1944, pp. 38-145; Edith Abbott and Sophonisba Breckinridge, The Tenements of Chicago, 1908-1935 , Chicago, 1936.

sidewalk was still a long step from installing taps, toilets, or tubs inside the houses. For the urban poor, a generation and even longer elapsed before owners of slum properties installed plumbing.[17] Within the boundaries of the private lot itself the city could only admonish, harass, and fine; it could not install or repair on its own initiative. Such was the tenderness of the law toward landlords that the tenant (and many more than half of America's city dwellers were tenants until after World War II) could neither withhold his rent nor sue for damages for his landlord's failure to comply with regulations. Nor could landowners compel the owners of nearby property to conform to the codes of the day, even though neglected, mismanaged property lowered the value of the entire block. So stubbornly has our law rejected the social dimensions of property ownership that even today tenants' unions, rent strikes, private rights of action for code violations, and municipally executed repairs stand in the vanguard of our urban politics and property law.[18] Meanwhile, everywhere in the vast aging tracts of our cities the private owner's personal profit, the tenant's poverty, the neighborhood's obsolescence, and the law's timidity conspire to maintain dangerous structures, and millions of houses, stores, and blocks stand well below current standards for a decent living environment.

In Europe, especially after World War I, when the limitations of regulation had become clear, cities undertook massive public housing programs. In Germany and Sweden substantial fractions of the building costs were offset by municipal participation in the land market. Cities, like private speculators, purchased outlying farms in anticipation of future growth, and in later years when these sites were developed for housing the municipality itself reaped the profit from its investment.[19] In America most cities were and are forbidden by statute and state constitution to enter the private land market freely, and neither city, state, nor federal government receives much popular support for major public housing programs. Compared to the rest of the modern world, we have started late and done little. As city dwellers, we have remained what we were as farmers: a nation of small proprietors, jealously pro-

[17] . Sam Bass Warner, Jr., The Private City: Philadelphia in Three Periods of Its Growth , Philadelphia, 1968, pp. 109-11.

[18] . National Commission on Urban Problems, Legal Remedies for Housing Code Violations, Research Report No. 14 , Frank P. Grad, ed., Washington, 1968, pp. 109-48.

[19] . Shirley S. Passow, "Land Resources and Teamwork in Planning Stockholm," Journal of the American Institute of Planners , 36 (May 1970), 179-88.

tecting our individual property rights as if they were the cornerstone of our civil liberties. Public housing here has been a mean and narrow philanthropy. We have steadfastly protected the privileges of millions of small owners and have refused to provide decent protection against rats, cold, disease, overcrowding, and fire for millions more.

The inability of such a tradition to cope with the positive issues of city building is nicely illustrated by the history of zoning. In this case the problem was to deal with urban growth, a new kind of downtown, and a new kind of residential area, instead of with residential obsolescence and lingering poverty. The response of the law, given its traditional mold, could be only regulatory, as it had always been. It attempted to order growth under the guise of preserving established values, allowing titanic costs to be pushed on those at the center of the metropolis, and it permitted the wholesale denial of civil liberties to be imposed at the growing residential periphery.

The standard zoning ordinance of American cities was originally conceived from a union of two fears fear of the Chinese and fear of skyscrapers. In California a wave of racial prejudice had swept over the state after Chinese settlers were imported to build the railroads and work in the mines. Ingenious lawyers in San Francisco found that the old common law of nuisance could be applied for indirect discrimination against the Chinese in situations where the constitution of the state forbade direct discrimination. Chinese laundries of the 1880s had become social centers for Chinese servants who lived outside the Chinatown ghetto. To whites they represented only clusters of "undesirables" in the residential areas where Chinese were living singly among them as house servants. By declaring the laundries nuisances and fire hazards, San Francisco hoped to exclude Chinese from most sections of the city and to break the Oriental monopoly of the operation of laundries. Indeed the first statute, imperfect as it was, threatened to put 310 laundries out of business. The San Francisco ordinance failed to pass in the federal courts because it gave arbitrary powers of racial discrimination to a Board of Supervisors.[20] The city of Modesto, however, used the device of dividing the city into two zones, one permitting laundries and one excluding them, and in this way squeezed past the constraints of the state constitution and the Fourteenth Amendment:

[20] . The San Francisco attempt foiled: Yick Wo v. Hopkins, Sheriff , 118 U.S. 356 (1886).

It shall be unlawful for any person to establish, maintain, or carry on the business of a public laundry or washhouse where articles are washed or cleansed for hire, within the City of Modesto, except within that part of the city which lies west of the railroad tracks and south of G street.[21]

Such nuisance-zone statutes spread down the Pacific coast. They were directed against laundries, livery stables, saloons, dance halls, pool halls, and slaughterhouses. In Los Angeles during the years from 1909 to 1915, successive ordinances culminated in something very like a modern land-use, structure-type zoning statute. The whole of Los Angeles was divided into three districts of specified classifications: one restricted to residences, in which only the lightest manufacturing was permitted, a second open to any sort of industry, and a third open both to residence and to a limited list of industries. The California precedents, when joined with the regulations of Washington, Baltimore, Indianapolis, and Boston in respect to fire precautions, building heights, and strictures on construction, served to create the New York Zoning Law of 1916, the prototype statute of the nation.[22]

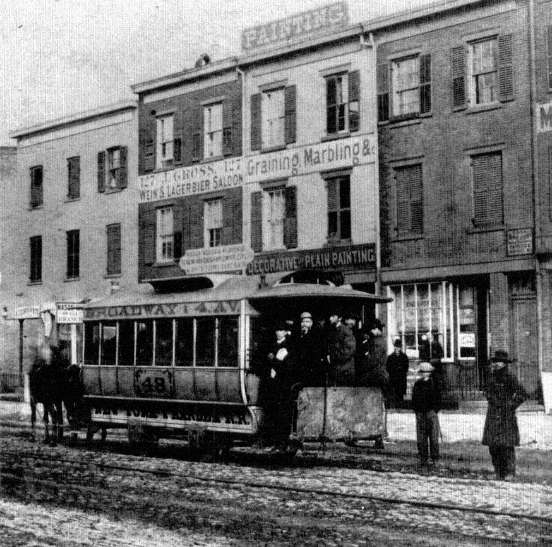

In New York a new high-density form of land use, the skyscraper, threatened the established functioning of the low retail blocks of the city. The earliest skyscrapers, though modest by today's standards, broke the traditional relationship between street width and building height which had controlled Western building for centuries. Masonry construction had hitherto limited buildings to a maximum height of six to eight stories. Then, with the perfection in the late 1880s of steel-frame construction, structures of from nine to sixteen stories became feasible.[23] Thanks to the urban concentration effected by electric street railways, elevateds, and subways, land rent skyrocketed in downtown areas, and in response to the soaring values steel frame skyscrapers mushroomed in Chicago and New York, at first for office buildings and later for department stores and factories.

In New York the Fifth Avenue Association, a group composed of men who owned or leased the city's most expensive retail land, demanded that the city protect their luxury blocks from encroachment by the new tall buildings of the garment district. The problem was quite

[21] . In re Hang Kie , 69 California 149 (1886).

[22] . W. L. Pollard, "Outline of the Law of Zoning in the United States," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science , 155 (May 1931), 15-33; John Delafons, Land-Use Controls in the United States , Cambridge, 1966, pp. 18-24.

[23] . Carl W. Condit, American Building , Chicago, 1968, pp. 124-30; Homer Hoyt, One Hundred Years of Land Values in Chicago , Chicago, 1933, p. 150.

specific. Jewish garment manufacturers had captured the national market for ready-made clothing by perfecting highly specialized methods of manufacture, and the rapidly expanding industry required more space than could be bought or rented in the congested lower East Side locale in which the Jewish firms had first located. Nearby real-estate firms thereupon assembled parcels occupied by small old buildings, which they tore down and replaced by eight- to twelve-story lofts for the garment manufacturers. By this process the garment industry had spilled over twenty blocks north of Fourteenth Street in the first decade of the twentieth century.[24] The Fifth Avenue Association feared that the ensuing decades would see the lofts invading their best properties, bringing with them lunch-hour crowds and a blockade of wagons, trucks, and carts. In short, they feared that skyscraper lofts, low-paid help, and traffic congestion would drive their middle-class and wealthy customers from the Avenue. The needs of the Fifth Avenue Association were met by joining their protests to those of other regulatory interest groups throughout the city, and a successful coalition for the passing and enforcement of zoning ordinances was formed.

It was a Brooklyn lawyer and politician who put together the ingredients that propelled the nation's zoning law and zoning policies. He was Edward M. Bassett (1863-1948), who had been serving on the State Public Service Commission that planned New York's subways. He established the practice whereby a zoning map would be drawn only after the most extensive hearings in the neighborhoods themselves, so that local landholding interests might participate. Indeed, the private property owners in the small areas of the city were in effect to draw the residential maps.[25] Such an inclusive administrative process could succeed because the rationale of zoning was aimed not at disturbing existing conditions but at projecting current trends into the future and perpetuating them. Nonconforming use of land remained, but it was hoped that adjacent majority practice would perpetuate the norm in subsequent years.

Bassett himself stressed the preservation of "the character of the district." In the suburbs zoning would protect homeowners by maintaining the uniformity of their neighborhoods, and real-estate men who held

[24] . Robert M. Haig and Roswell C. McCrea, Major Economic Factors in Metropolitan Growth and Arrangement, Regional Survey of New York and Its Environs , v. 1, New York, 1927, pp. 80-94.

[25] . Stanislaw J. Makielski, Jr., The Politics of Zoning: The New York Experience , New York, 1966, pp. 7-40.

vacant land could proceed to build upon their small tracts in confidence that the adjoining ones would be improved according to the uses specified on the zoning map. One-, two-, and multiple-family houses would spread out in orderly paths, while apartments would march along the principal streetcar lines and cluster at the subway stations. For the dealers in commercial real estate the zones stabilized the current downtown and suburban uses, leaving abundant room for the future growth of industry and commerce. Zoning in sum contravened none of the expansion patterns of the city, but it did protect all classes of residents from the most unscrupulous and speculative use of individual parcels of land. Furthermore, it encouraged uniformity of development, which by then had become the fashion of the real-estate industry. So popular was the New York Zoning Law of 1916 that it was copied by 591 cities in the next decade. Bassett himself was invited to draft a model statute for the United States Department of Commerce, and this was widely adopted after its publication in 1924.

According to this standard form, a typical zoning law consisted of three elements. First, there was a map of the city on which all private land was assigned to a particular area or zone. Second, the restrictions applying to each of these zones were itemized. They included the height, number of floors, and general size of any structure that could be permitted in the future to be built on land in a particular zone. In addition, the percentage of the lot area that might be covered by building, the size of yards, courts, and open spaces, and the population density were all specified. Third, calling upon the precedents of the past half century, there was a recital that this set of restrictions on private property was legitimate and constitutional because it represented the traditional exercise of police power in cities and states and that it was directed toward the protection of the health, safety, morals, and general welfare of citizens; that these principles could best be served by preventing overcrowding, facilitating transportation, conserving the value of existing property, and guaranteeing adequate light and air in all habitations.

As the years passed and the patterns of growth and decay in the city shifted from the density of the early twentieth century to the diffused multicentered megalopolis of the post-World War II era, the consequences of zoning became clear. Just as zoning had given the wealthy retailers of Fifth Avenue a means of defense against the encroaching garment factories, so subsequent zoning gave suburbanites a defense against "undesirable" activities and people. No sooner had the New

York ordinance been passed than the South seized upon the device as a way to extend its laws and practices of racial segregation. A Louisville ordinance creating zones for whites and for blacks was declared unconstitutional in 1917 in the case Buchanan v. Warley ,[26] but more subtle zoning refinements continued to plague the courts until 1948. Everywhere zoning laws interacted with real-estate prices to reinforce segregation by income, national origin, and race within the cities. Stipulations in zoning ordinances that single-family homes should prevail over two-family homes or apartments, or that one-acre lots were to be required instead of quarter-acre lots, had powerful social repercussions in a society of mixed population and markedly unequal distribution of family income.[27] A land or structure limitation therefore became a financial, racial, and ethnic limitation by pricing certain groups out of particular suburbs. Italians were held at bay in Boston, Poles in Detroit, blacks in Chicago and St. Louis, Jews in New York. At times, especially during the 1920s, racial and ethnic covenants conspired with zoning to prevent "non-Caucasians" (Jews, blacks, Orientals) from even purchasing land. Such practices struck at the root of the ancient justification of American land law. By severing the connection between personal freedom and property ownership, the very being of our law which held private property to be the basis of a man's civil liberties perished. In 1948 the Supreme Court finally ruled such contracts unenforceable,[28] but the class and racial consequences of the interaction between the unequal distribution of income and zoning spread unabated.

Zoning, as planned and executed by each political subdivision of the industrial metropolis, also lashed city building to petty political divisions and produced the same conditions that later hamstrung the federal grants-in-aid program for public housing. Each city and town in the emerging megalopolis was a zoning entity. During the twenties real-estate dealers' enthusiasm for expansion and for uniformity of practice lessened the differences among suburbs. The Babbitts controlled the politics of most suburbs, and they mapped generous tracts for all kinds of new building: for modest homes, apartments, and shopping streets. Their social generosity was spurred by the knowledge that subdivision and store building offered the highest profit to the land developer. The

[26] . Buchanan v. Warley , 245 U.S. 60 (1917).

[27] . According to a recent estimate, two-thirds of the zoned vacant land in the New York Metropolitan Region now calls for one-family houses on lots of half an acre or larger, and almost half of this land is zoned for lots of one acre or larger. Regional Plan Association, The Region's Growth , New York, 1967, p. 68.

[28] . Shelley v. Kraemer , 334 U.S. 1 (1948).

real-estate man, except in a few of the wealthiest suburbs, was not the enemy of the lower middle class in their advance out of the core city but a booster who tried to promote their exodus.

After World War II the diffusion of the automobile quickened the pace and lengthened the reach of the urban middle class and even of the working class and thereby made suburbanization possible for a larger mass of people than in the twenties. A different attitude, however, now appeared among the older residents of suburban communities. Instead of seeing all growth as good, selling their property for a profit and moving on, as they would once have done, they now tried to use zoning to protect their established pattern of light settlement against developer encroachment, to defend their comfortable style of low-density living against a cheaper and more congested style. Also frequently now, a particular social group—white Protestant, Jewish, or Catholic—was resisting new classes, new ethnic groups and races. Accordingly, regulations that limit an entire town to single-family occupancy or to minimum lot sizes of one, two, or even four acres have been enacted in order to preserve intact the existing social context of lightly settled suburbs.[29] The established residents, having lost faith in the value of continuous growth, see no improvement in their towns as development robs them of their view, their orchard, or their beach, however much development may raise the value of property in general. They are in fact fighting for what they regard as their de facto rights in the unused farmlands, fields, or woods adjacent to their own land. The established have increasingly fought, and are still fighting, many of the suburban developers within the megalopolis in an effort to block the granting of variances or the alteration of old zones to include apartments and shopping centers, sometimes whole new suburbs.

By and large, suburban defenses since the Second World War have enabled a significant number of well-organized communities to limit their growth by halting or delaying development. But the cost has been high. These campaigns have added a new level of antisocial bias to the ordinary life of America. The success of one town in halting development implies an ability to ignore the legitimate needs of its neighbors. The fact that the builders of downtown skyscrapers were seizing light and air and street use from their neighbors was a salient motive for zoning in the first instance, and their behavior is now echoed on a wider

[29] . David S. Schoenbrod, "Large Lot Zoning," Yale Law Journal , 78 (July 1969), 1418-41.

scale as the wealthy and the firstcomers join hands to seal off the best land of the megalopolis from the mass of their fellow citizens.[30]