10—

Yüan Chieh (719–772)

Yüan Chieh was an innovative writer of the mid—eighth century and an early exponent of the Ancient Style prose movement. Born in Lu-shan, Ho-nan, he arrived in Ch'ang-an in 747 but, owing to political obstructions, did not pass the examinations until 755, the year the fateful An Lu-shan Rebellion broke out. His early poems reflect his frustration over failure to obtain an official post; the themes include satiric critiques of the political world, the decadence of urban life, and yearnings for Taoist purity. During the rebellion, he led his family south to modern Hu-nan for safety and in 759 raised troops in Ho-nan for the T'ang cause. For this, he was rewarded with various official positions, including those of palace censor and administrative assistant to a military commissioner. In 763, he served as prefect of Tao Prefecture in Hu-nan, where he pacified the local minority population and alleviated the economic exploitation of the people by the T'ang authorities. In 768, he was posted to Jung Prefecture in what is today Chiang-hsi, where he showed the same kind of compassion for the inhabitants. It is the writings of this mature period on which his later fame was based. Yüan urged that literary forms convey the values of the Confucian classics and objected to the purely decorative elements and formal rules that still characterized much poetic writing and parallel prose. Later critics saw his poetry as based on the direct expression of emotion rather than on stylistic issues, though some considered his work excessively plain. His prose writings were mostly incisive and thought-provoking discussions of social problems.

Yüan's travel pieces were written while serving as prefect of Tao Prefecture. In The Right-hand Stream , he evokes a neglected lyric scene,

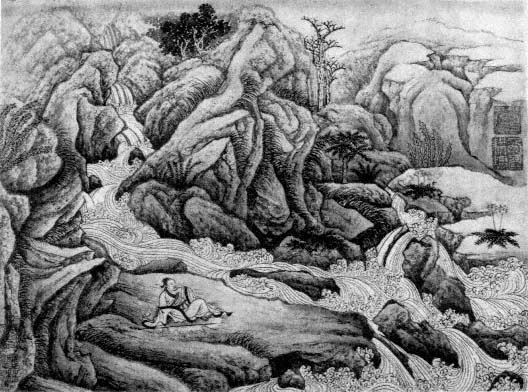

Fig. 17.

Attributed to Lu Hung (active first half of 8th cent.), album leaf from Ten Vieu's of the

Thatched Cottage . National Palace Museum, Taipei.

rescuing it from oblivion by naming it and aesthetically restoring it with landscaping and buildings. The pity that the place inspires in Yüan Chieh is a personal expression of the loneliness of an official posted far from the capital. A similar feeling pervades My Own Terrace , in which the author plans to construct a vantage point from which to gain the "grand view" of reality—a sublime substitute for the power center of the capital. The Winter Pavilion was written in the summer of 766 while Yüan was on an inspection tour of Chiang-hua. At the request of the local magistrate he bestows a name on the pavilion, one based on his subjective response to the scene. Both The Right-hand Stream and My Own Terrace were originally written as prefaces to a ming , a short,

formal inscription in parallel prose that was engraved at a site. All three pieces anticipate the exilic travel accounts of Liu Tsung-yüan. My Own Terrace , in fact, was located in Yung Prefecture, where Liu Tsung-yüan was later exiled. Liu visited it, and Yüan's account may have had a direct influence on his writings.

The Right-hand Stream  (ca. 764)

(ca. 764)

A hundred or so paces west of the seat of Tao Prefecture[1] is a small stream. It flows south for tens of paces and then joins Ying Stream.[2] The water strikes against the banks, which are formed by odd-shaped rocks. Jumbled and tilting, they wind along and jut in and out—the scene defies description. When the clear current collides with these rocks, it swirls, surges, becomes excited, and rushes forward. Fine trees and unusual bamboo cast their shadows, covering one another.

If this stream were located in a mountainous wilderness, it would be a suitable spot for eremites and gentlemen out of office to visit. Were it located in a populated place, it could serve as a scenic spot in a city, with a pavilion in a grove for those seeking tranquillity. And yet, no one has appreciated it as long as this prefecture has been m existence. As I wound my way upstream, I felt quite sorry for it.

So I had it dredged of weeds in order to build a pavilion and a house. I planted pines and cassia trees, adding fragrant plants among them to augment the scenery. Because the stream is to the right of the city, I named it "The Right-hand Stream" and had a ming inscription carved on one of the rocks to explain this to all who come by.[3]

The Winter Pavilion  (766)

(766)

In the year ping-wu of the Yung-t'ai era [766], I was on an inspection tour of the districts under my jurisdiction and arrived at Chiang-hua.[1] The magistrate, Ch'ü Ling-wen,[2] consulted me thus: "In the south of this district, a stream and a rock reflect each other and it is a lovely sight. It was said that one could not climb up there, but I sought a way. I came across a cave and entered it and built a walkway over the

dangerous sections so that I could pass. Thus, I was able to construct a thatched pavilion on top of the rock. Once the pavilion had been completed, stairs and railings were built projecting out from the rock as it looks out on the lengthy river below.[3] The pavilion's pillars and roof mingle with the clouds and are as high as the summit. When the atmosphere is clearest at dawn and at dusk, the mist appears in unusual colors; the surrounding, blue-green rock wall reflects the water and the trees. I wanted to name this pavilion but could not find the words to describe it. I venture to invite you to name it for all generations to come." So I discussed the matter with him at the pavilion, saying: "Though I visited this at the height of summer, it feels as if the season will soon turn to winter. Though located in these torrid parts, it is cool and comfortable. Is it not appropriate to name it 'The Winter Pavilion'?" So I wrote out this record for the Winter Pavilion and had it engraved on the rear wall.[4]

My Own Terrace  (767)

(767)

More than two hundred feet northeast of My Own Stream,[1] I came across a fantastic rock. It is three or four hundred paces in circumference. From the hours of wei and shen [1:00–5:00 P.M.] to ch'ou and yin [1:00–5:00 A.M.], its cliff blocks out the stars of the Northern Dipper, but during the remaining hours the light returns and all is visible. In front is a flight of stairs eighty or ninety feet high, which leads to a swirling pond below. Steep and precarious, half the stairs extend down to the water's bottom. They appear greenish and undulating as if they were on the surface of the ripples. I plan to build a cottage on top of the rock in an unusually scenic spot. The hollows on its small peak are just right for planting pines and bamboo. These will screen the windows so that it will be completely secluded. Alas! Among the ancients were those who felt angry and depressed or were sickened by the ways of the world. They lacked the funds to build lofty terraces from which to gaze down upon it all. Instead they sought out the summit of a mountain or the edge of the sea to sing out at the top of their lungs and feel exultant. Now, I have taken possession of this rock and will construct My Own Terrace, not out of melancholy or complaint, but only because such is my pleasure.

The ming inscription says:

The Hsiang River's chasm is clear and deep; My Own Terrace is steep and precipitous. I climbed up and gazed afar; not a thing escaped my sight. To whomever is wearied of court and city, or feels harnessed and confined, I offer the use of this terrace to instantly relax your mind and eyes. The cliff on the south has been polished smooth, like a gem, like alabaster. I have written this inscription and had it engraved to make this known to all to come.[2]

Fig. 18.

Printed text of The Pavilion of Joyous Feasts (detail). From Han Yü,

Ch'ang-li hsien-sheng chi (1174). National Palace Museum, Taipei.