Chapter Sixteen—

Steelie

Paul McHugh

It took a long time to find them. I'd glimpsed the silvery torpedoes of the steelhead trout—those huge, sea-wandering rainbows—when they thrashed up the waters tumbling down the old fish ladder at Van Arsdale Dam on the Eel River. But the vision only whetted my thirst, stimulated my imagination. I'd heard so much about these magnificent game fish, how they struck a lure like lightning, and fought like tigers once hooked. And more significantly, how they fought their way home to spawn, leaping even further up the whitewater of California coastal streams than salmon. . . . And how their life cycle, when permitted to play out, revealed California mountain forest, cool stream, and vast sea as connected in one organic whole.

On the North Coast, a steelhead has the potent status of a totem animal—it stands for all that is best about all that's still wild here. So even a dramatic glimpse of them struggling upstream against the swollen waters of the Eel wasn't enough. Their ancestral home was what I wanted to see, the clean gravel shoals of the upper headwaters. The place where these fish spawned, and their forebears before them. Where the waters contain a unique chemical "thumbprint," a faint smell that persists in the river's outflow some two hundred miles downstream. A taste of home, which these fish had sensed, and recognized, and turned toward weeks earlier as they swam the ocean coast off Humboldt County—as we might recognize the strains of a song unheard since childhood.

Sensitive to chemicals at the subtle level of parts per billion, they had noted and recognized the waters of this river estuary from scores of them along the California shore. They had run the gauntlet of sea lions, harbor seals, and human anglers at the delta mouth. Then a cold winter storm had swept over the Coast Range, and the spate of water rushing downstream had sent another signal to electrify the nerves of these powerful fish. Now. The time was now. It was time to go home. The water would be deep enough to leap the chutes of the rapids, cold enough to ensure the survival of eggs after spawning.

I started my hike up Bucknell Creek late on an overcast day, not long after a major storm. Twists and turns of the canyon, walls of tangled brush and jumbled rock, meant that soon I had to hike in the frigid creek itself. Soon after that it fell dark, and I sought a campsite.

When I awoke the next morning, my old army surplus bag was coated with a quarter-inch of hoarfrost. My shoes and socks were frozen stiff. Laboriously, I collected dry twigs from the ends of oak branches to make a fire that would thaw and dry them enough to wear. But within an hour, I found myself hiking in the footnumbing water again. Past streambanks lined with drifts of old snow. Up boulders upholstered with frozen moss. Along jams of slippery logs. But every once in a while, I would see a long silver flash in a pool that would tell me the fish were still here, still traveling upstream. Once I even saw an improbable leap, a soaring, gymnastic effort that carried a big fish up and over a cataract to flap once or twice on a shallow rock and then slip safely into a pool.

Part of me felt pulled along by the drive of the steelhead toward the headwaters, a bullish determination to succeed at all costs. It was as though a part of my mind and heart had identified with them, and I continued long after my legs lost sensation below the knee due to the cold. Following the way of this totem animal, I continued fighting upstream until finally I found myself clinging by my fingertips to a steep canyon wall with no possible way to move even an inch further ahead, and facing a terrifying fall onto the rocks of a rapid below if I even tried.

The steelhead were still moving upstream as, defeated, I made my way back to my car by sunset and drove home. And fell into a week-long fever from the overexposure and exhaustion, with my

temperature sometimes spiking to a neuron-threatening hundred and seven degrees. When my housemates brought me in to the emergency room, blood tests revealed no infection by virus or bacterium. But perhaps modern medical science has no way to treat someone who has temporarily lost a piece of his soul to a fish.

Weary of the strange dreams and visions of sickness, I at length broke the fever by opening my bedroom window and letting the cool winds of the new storm wash over my body.

After my strength returned, I went back to the headwaters of the Eel River. And finally, after hiking up another creek where I could stay on the bank, I found them. It was a clear crisp day, the sort of winter morning when brassy sunshine comes shouting down through cerulean skies. As I came around a bend in the creek, there they were, metallic bodies flashing in the sunlight as they sparred and mated in the crystal shallows. The silvery torpedoes of the males, darting against each other, shoving competitors into jets of current where they would be washed downstream. The long large female, weighing twenty pounds or more, her body flashing rainbow markings and the bright red blotches that steelhead acquire after their return to fresh water. I watched her turn on her side to dig her redd in a shoal of gravel with powerful thrusts of her tail. The victorious male joined her then, and their bodies shivered in muscular spasm, side by side, as the eggs drifted down into the nest through a cloud of milt.

Ah, the passion and raw power and wild beauty of that! When people mention the glory of the wild earth, this is my image—that supreme moment steelhead achieve after the ordeal of their pilgrimage, touching in the cold, clear creek, bodies spattered by sparkling chains of sunlight, the whole scene framed by forest and snowy hills.

We learn something important from watching the steelhead. They can remind us that some of the same force driving them impels us. Though at times its power is half-strangled by the fear or doubt in our trepidacious human minds. Though at times that force is hyped and distorted by those trying to sell our wildness back to us without a clue as to its essential dignity.

Unlike the salmon—who ascend their home rivers just once, to spawn and die in an orgiastic finale that seems the closest thing in the animal world to Greek tragedy—steelhead trout embody a

tougher optimism. A few will survive, rest briefly, then head back out to sea, and return another year, and then the year after that, to repeat the arduous challenge of the spawning cycle. If they can.

The presence of wild steelhead and salmon in California rivers is charming, magical, fascinating. But—if you're aware of it—contrasting that rich presence to their absence can have an even stronger impact.

In Trinity County I was privy to a scene that suggested the glories of the past. Jim Smith, a World War II vet and county supervisor, stood in a long, dry gulch of rounded stones near his home. In an emotional voice, he told me about the salmon and steelhead runs that he'd seen here when he came home after the war. Runs that were nearly extinguished when a huge federal dam and diversion project took most of the Trinity River's water away in the 1960s.

"From hundreds of yards away, you could hear a bedlam of splashing, like kids in a swimming pool. The river was a series of big deep pools and long stretches of gravel with just enormous redds of salmon. You could wade out into the middle, and there would be salmon spawning everywhere around you. If you stood still, you were like a tree or anything else: fish would drift into the eddy of your legs.

"There'd be a pack of steelhead kind of idling downstream of a redd. One would reach in and lure the male off into an attack, and the rest of the steelhead would gobble up the salmon eggs. How could there be reproduction with that much predation? Well, the reproduction was just that much heavier. But personnel in the agencies don't believe me when I describe this because they have no experience or frame of reference for it; it just doesn't make sense to them."

The most poignant part of Jim Smith's story to me was not the loss of this scene of intense biological beauty from his childhood—all of us who grew tip in the backcountry in the twentieth century have similar stories to tell—but what he subsequently did about his loss. For the next two decades, Smith fought in the political arena for restoration of the Trinity River. He gave endless interviews and speeches, wrote letters, organized committees, criticized studies and the bureaucracies that spawned them, and found like-minded souls in various agencies with whom to ally himself in the struggle.

And today, increased water flows are being returned to that ravaged stream. New spawning riffles have been built. A federally financed sediment catchment dam has been approved to reverse some of the damage. And the heroic efforts of an underbuilt hatchery are finally bearing fruit. And it was here that I finally felt the excitement of a tug-of-war with a steelhead at the other end of the line. My 1986 small fish, part of a run of "half-pounders," was a far cry from the hefty eight-and-a-half-pounder that was Bing Crosby's first steelhead, taken on a fly from this same river in 1963. That was the year the big water diversion dam was completed and the fish runs began their dramatic slide toward oblivion.

But if my fish was small, it was still part of a much larger run, numerically, than the mere thirteen steelhead that showed up here to spawn in 1977. The efforts of Jim Smith and his friends and allies were starting to pay off.

Once there were steelhead spawning in coastal streams as far south as Mexico. Once nearly all the northern California streams were choked with vibrant salmon and steelhead runs. Twentieth-century civilization has attacked them in ways almost too varied and numerous to catalog: water diversions and dams; siltation from road-building and logging; overfishing with instream gillnets; and pollution of various sorts.

The only really heartening part of the picture is the way that humans have also sought to make amends for their depredations. I remember volunteering for a few days on a project to clear old logging debris from the Albion River. Every summer morning that year in 1976, young people would stumble down into the cold river water to breathe chainsaw fumes and wrestle with wood, mud, and steel chains just to remove obstacles and improve the chances of the river's remaining steelhead runs. That gritty Albion River restoration scene, like Jim Smith's ultimately productive jog on bureaucratic and political treadmills, has also been repeated in various river valleys up and down the coast.

Some of that immense effort has been doubtless due to selfish motivations. After all, life provides few thrills like the one that comes when a big wild steelhead inhales your lure and sends the unmistakable quiver of the presence of a powerful life back up your line. It's like the tingle that precedes a thunderbolt, because the very next thing which happens is that the surface of the water

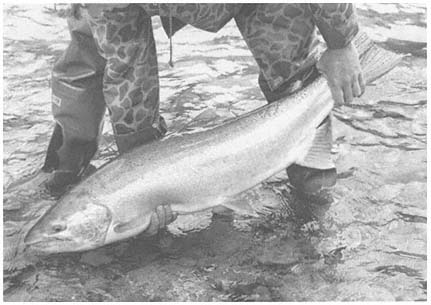

Catch 'em and let 'em go. Catch-and-release fishing is encouraged as one

means of preserving steelhead stocks.

(Herbert Joseph)

explodes and the fish tries to tear the rod out of your hands, or, failing that, strip all the line from the reel in a screaming downriver burst of speed. It is not given to us to touch very many wild beings in that way. I am thinking now of a specific twelve-pound wild steelhead on a northern river in 1987.

But I like to think that a lot of the work for the well-being of salmon, steelhead, and rivers comes from a deeper motivation: the understanding that steelhead are canaries. That's right, canaries. You've heard this metaphor before, but it's certainly true enough to bear repetition. In the old days, coal miners would bring a caged canary down with them in the shaft. Because the birds were so sensitive, miners knew that if the canary ever stopped singing and fell to the base of its cage, it was a warning that a poisonous gas was spreading, and it was time to drop their tools and get out.

In the same way, vibrant steelhead runs are a living testimony to the health of the streams, the forests that surround them, and the oceans that are their vagabond home. When we can no longer

maintain runs of wild steelhead, an important quality of life will be dying. And soon after that, life itself for us may become rather difficult. So we try to reverse our damage, and keep them alive in the hope that we ourselves may survive as a species.

In the course of writing this piece, I've taken a few chances and talked about some things that I've never spoken about to anyone before. I'd like to continue with one final stretch for a piece of truth.

Once I got into trouble with the editor of a publication I worked for because I ran a photo of a man getting ready to eat a raw tuna heart. The man had just fought and landed his first big albacore tuna. The tradition of this particular tuna boat was that the angler was then presented with the fish's raw heart and commanded to eat it. In the photo the man's grin looks a little tight, but he has a can of beer in his hand to wash it down, and it's clear he's getting ready to do the deed.

The editor's position was that this primal image was going to make most of the readership feel like throwing their breakfast right up onto their morning paper. I acknowledged he was probably right, but I was still glad I'd run it. Because, in my opinion, we are a little too far away from the primitive belief that we take on strength from the things we fight, and the things we eat. And because if we are too squeamish to know the taste of the heart of a fighting fish, maybe we'll wind up too squeamish to get down in the muck with a saw and jam dirt under our fingernails as we work all day to partially restore a ruined river. Maybe we'll wind up without the grit and persistence we'll need to plumb the depths of our convoluted bureaucracies and emerge on the other side with the prize of a coherent policy.

A coherent policy that allies us with the wild beauties of our environment; instead of one that compels us to destroy them.