IV

The Sanctuary of Zeus

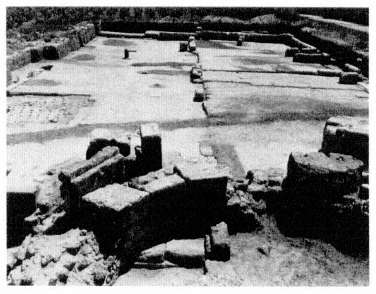

The Houses

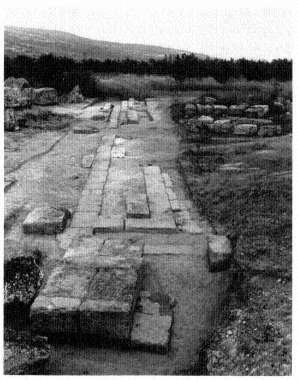

A flagstone path links the museum and the Temple of Zeus north of it. After descending a few steps into the excavation zone, the path continues northward between ancient buildings to an abrupt westward turn (Fig. 22). These buildings are large complex structures built up against one another except where the narrow path runs between them. Facing north onto an ancient east-west road, the gravel layers of which are below the modern path, these units were built mostly in the last quarter of the 4th century B.C . and were out of use by the

Fig. 22.

Detail of the general size plan, showing houses.

middle of the 3rd century or earlier. In the second half of the 3rd century a small isolated area to the east was built over and used briefly; in the 2nd century B.C . an equally small and isolated region to the west in House I was reused. The shift of the Nemean Games to Argos is made dramatically clear in this region (see p. 57).

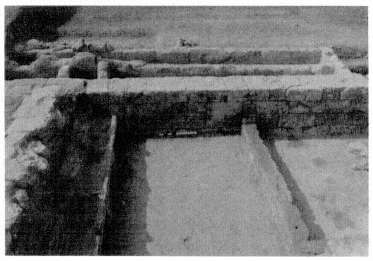

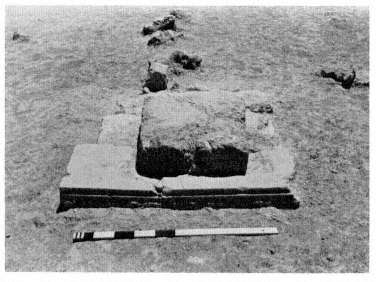

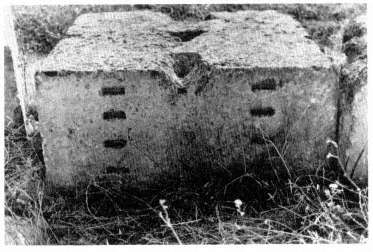

These structures have been labeled houses because of the domestic character of their contents. For example, evidence of cooking was discovered in one room of House 4 (the second room east of the turn in the path): a small stand for the support of cooking pottery, made of three Lakonian tiles placed on edge to form a vertical vent. Some of the ash and burnt earth surrounding these tiles remained as a kind of plaster on the adjacent walls (Fig. 23). Similarly, in several other rooms of these houses, hearths or other evidence of cooking was discovered. The well in House 3 (to the southwest) also suggests a domestic function. It is marked by a large square block into which the circular mouth has been carved. (The shaft of the well is lined with rubble construction to a depth of 5.75 m., after which it continues unlined to a depth of 7. 10 m.)

If hearths and a well suggest domestic uses, still the walls of the houses, especially along the facade, were built of blocks larger than those commonly used for houses. In other places (the north-south wall of House 4 immediately east of the path) the top of the rubble wall is covered with tiles which served as a leveling course for mud-brick or adobe walls higher up. In addition, these buildings are much larger than the typical house of the period at other sites, and they do not present the stratigraphic accumulation one expects in the domestic quarters of a true habitation. That they were an official, albeit subsidiary, part of the Sanctuary of Zeus is evident in the artifacts discovered in them which are labeled as belonging to Zeus, such as the mug in case 6 of the museum (P , 778; see p. 32), or in other artifacts which are official by

Fig. 23.

Cooking stand in House 4, with marble relief(ss 8, now in the

museum) still in situ in the foreground, from the south.

their nature, such as a bronze weight of Argos (Fig. 24).[44] These houses, then, are perhaps best interpreted as the official quarters of priests or judges (the Hellanodikai ) or caretakers of the sanctuary during the biennial games, not as the domiciles of a permanent population at Nemea during the Classical or Hellenistic periods.

Fig. 24.

Bronze weight (BR 1194).

[44] Such items show dearly that Argos was in control of the Nemean Games in the Hellenistic period; see pp. 20, 57, 61-62.

The Basilica and the Early Christian Community

To find a settlement of permanent residents who lived, worked, and died on the site, we must look back to the Neolithic and Bronze ages or ahead to the later history of the Nemea valley and the small farming community of Early Christians which grew up among the ruins of the ancient sanctuary in the 5th and 6th centuries after Christ.[45]

When the flagstone path turns left, it follows the line of the main ancient east-west road through the valley. In the distance to the north are the three standing columns of the Temple of Zeus; but just north of the path, about chest high, are the remains of the Basilica which served as a focus for the Early Christian community. Beneath these remains are those of the Xenon. A short distance further on the path, cut into a wall and protected by a modem cover, is a Christian burial typical of those found at Nemea. In a grave lined and covered with rough stone slabs, the body was laid with the head at the west, propped up to face east in characteristic fashion, awaiting the Resurrection and the Last Judgment. (See p. 93 for a general discussion of Early Christian burials.)

Beyond the grave, a short flight of modern steps leads up to the level of the floor of the Basilica, from which the remains are best viewed.

The Basilica was first excavated in 1924. Shortly thereafter, a large quantity of stone, once part of the fabric of the build-

[45] The geographer Strabo places between Phlious and Kleonai both the Sacred Grove of Nemea and a village (kome ) called Bembina. The village was apparently quite old since it was already known to the fifth-century B.C . historian and ethnographer Hellanikos (who calls it a city [polis ] rather than a village and gives the name as Bembinon) and his contemporary the epic poet Panyassis, uncle of Herodotus (who speaks of Herakles' battle with the "Bembinatin lion"), both of whom are cited by Stephanus of Byzantium, a scholar and antiquarian of the 5th century after Christ (Ethnika, s.v . Bembina). No trace of this Bembina or Bembinon has ever been found, however, and despite the testimony of Strabo the town may have been located some distance from the Sanctuary of Zeus, perhaps even outside the Nemea valley. Cf. the statement of Pliny the Elder (NH 4.6.21) that the regio Nemea between Kleonai and Kleitor—a distance of some forty miles—was known as Bembinadia; it is by no means clear where in all this area, which contains several important ancient sites, the town of Bembina itself was to be found. For the moment we can say only that no evidence of a regularly inhabited site of Classical, Hellenistic, or early Roman date has been found in the valley.

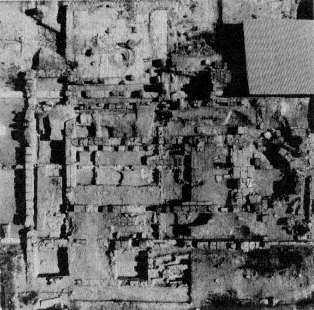

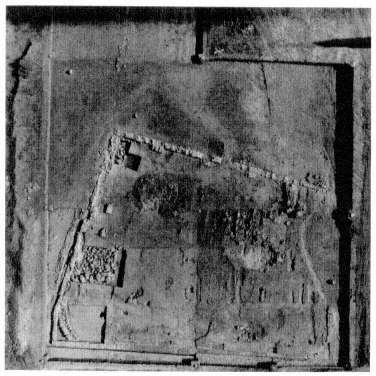

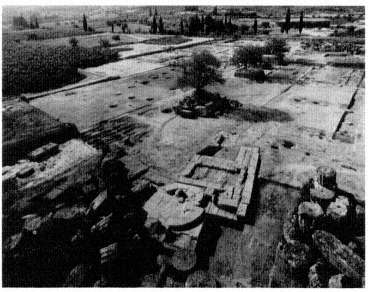

ing, was removed and used in the construction of a protective shed which stood until 1987 over the southwestern part of the Bath. This plundering of a Christian building in the interests of preserving pagan antiquities was carried out with a certain ironic propriety, since the Early Christians themselves had plundered the Temple of Zeus and other pagan monuments in the sanctuary in order to construct their Basilica. Together with the removal of additional blocks to the museum and the more haphazard destruction resulting from sixty years of exposure, however, this plundering has undoubtedly left the remains of the Basilica less easy to understand and appreciate today. Furthermore, most of the interior of the Basilica has been excavated far below the original floor level in order to reveal parts of the ancient Xenon which lies directly beneath it. As a result, the site occupied by these two buildings can seem at first a confusing jumble of walls running in all directions. With the help of the aerial photograph (Fig. 25) and the plans (Fig. 26; see also Fig. 30), however, and by observing that the reused wall blocks of Temple limestone resting on the Basilica foundations have weathered to a dark gray and lie at a higher level than the lower, mostly lighter colored, poros and rubble walls of the Xenon, we can follow the lines of the Christian building with some confidence.

The original basic plan (Fig. 26) is simple. A broad central nave (ca . 23.50 m. long and 7.50 m. wide) is flanked by aisles the same length, each roughly half the width of the nave (ca . 3.50 m.). The nave ends in an apse, which projects beyond the straight eastern walls of the aisles and increases the

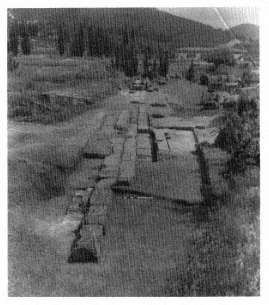

Fig. 25.

Aerial view of the Basilica, 1980.

length of the Basilica by 4.50 m. West of and perpendicular to the nave and aisles lies the narthex (ca . 16.50 by 4.50 m.), the lines of which are extended north and south beyond the aisle walls by two small side rooms (each ca . 4.50 m. square). Typical of small local churches of the 5th and 6th centuries throughout Greece, the plan as well as the size is also similar to the remains of a basilica (Fig. 27) at the top of Evangelistria Hill, the prominent peak south of the sanctuary easily identified by the modem chapel at its summit. This chapel in fact lies adjacent to the Early Christian church, which has been partly investigated but remains virtually unpublished.[46]

[46] A short paragraph of description and a small plan (Fig. 27 here) were published by A.C. Orlandos in Actes du Ve congrès international d'archéologie chrétienne , 1954 (Paris 1957) 112.

Fig. 26.

Restored plan of the Basilica with phases.

We begin a more detailed examination of the valley Basilica at its western end,[47] where the west wall of the narthex provides a good illustration of the types of construction used in the building. The foundations are of rubble, a mixture of unworked fieldstones, fragments of earlier buildings, and terracotta tiles, all set in a matrix of strong cement. Above them rose the Basilica walls proper, constructed of cut limestone

blocks laboriously transported from the Temple of Zeus; along the western side of the narthex, as at most points in the Basilica, little more than a single course of this wall is preserved, more or less at the level of the floor. The masons' marks—small letters carved into the upper surface of the blocks along the center of the wall—are unrelated to the position of the blocks in the Basilica; they date instead from their original use in the cella wall of the Temple. Considering the difficulty and expense of hauling good stone into the Nemea valley and the poverty of the Early Christian settlement here, it is hardly surprising that the remains of the ancient sanctuary were actively quarried for building material, a practice continued by the inhabitants of the local villages into the present century.

The narthex contains the largest preserved patches of terracotta tile paving in the Basilica, one in the northeastern corner, another further south, midway between the east and west walls; a few fragments are also visible elsewhere in the building. This paving, composed of yellowish orange tiles roughly 0.30 m. square (an example is displayed in the museum; see case 11, p. 47), once covered the whole of the narthex, nave, and aisles. It was badly damaged in places by medieval graves which cut through it, and some of it had to be removed when excavation inside the Basilica continued below the floor level.

The narthex, an invariable feature of Early Christian basilicas in Greece, served as a vestibule for the church. It communicated with the nave and aisles through three doors in its east wall; the thresholds of two (those leading to the nave and the north aisle) are preserved. The central doorway was naturally the most important: considerably wider (nearly 3.00 m.) than the others, it had a threshold constructed of three reworked ancient blocks, the westernmost of which is now cracked. Two doorways in the west wall of the narthex, one opposite the entrance to each of the aisles, provided access from the outside. The threshold block of the south door now sits

Fig. 27.

Sketch plan of basilica on the Evangelistria Hill, from A.C.

Orlandos, Actes du Ve congrès international d'archéologie

chré-tienne, 1954 (Paris 1957) 112.

slightly askew on the foundations of the outer wall; that of the north door is missing.

Threshold blocks are also visible in the north and south walls oft he narthex at the entrance to each of the small square rooms. The precise function of these rooms is unknown, and they may have been used for a variety of purposes. The southern one in particular, perhaps in conjunction with the slightly later room adjoining it to the east, may have served as a diakonikon , or vestry, one of the functions of which was to hold the gifts of the community. In the 5th and 6th centuries after Christ members of the congregation regularly brought to church private offerings of grain, olive oil, and wool as well as the bread and wine used in the celebration of the Eucharist.

The nave of the Basilica was separated from the aisles by rows of columns, most likely five or six to a side, made of drums reused from the interior Corinthian colonnade of the

Temple of Zeus. These columns, as comparison with other basilicas of this date in Greece suggests, would have rested on an elevated stylobate, or line of column bases, while low parapets in the intercolumniations would have prevented any direct circulation between the nave and the aisles. A block, decorated with a large incised cross in a square field, perhaps formed one of these parapets; that block now sits against the stylobate of the northern colonnade not far from the eastern end, facing the nave. Such a barrier both maintained a clear distinction between the clergy performing the service and the communicant but nonparticipant congregation, and kept the nave free of obstructions for the ceremonial processions which still form an important part of the Eastern rite. The congregation was also strictly segregated by sex: in larger, more opulent churches, the women were regularly isolated in galleries built over the aisles and furnished with independent entrances, but at Nemea, as in other small churches, this requirement was probably satisfied simply by placing men and women in separate aisles. (The tradition that assigns men to the right aisle and women to the left, although beginning to die out, continues today in the Orthodox churches of Greece, particularly in rural regions.)

The interior decoration of the Basilica was spare and simple, as befits the parish church of a small agricultural community. No trace of sculptural ornament or mosaic has survived, and the floors were roughly paved with plain terracotta tiles. The walls of the nave and aisles, however, and presumably the narthex as well, were covered with stucco and brightly painted. Pieces of plaster found during excavation preserved clear traces of paint: the color scheme included red and yellow in the nave and (less securely) muted blue in the aisles; the details of the decoration, however, are lost.

At the eastern end of the church, occupying the entire apse and extending some 3.50 m. into the nave, is the bema , or sanctuary, which contained the altar table and the synthronon ,

a semicircular podium with seats for the officiating clergy. The bema was separated from the nave by a wall or screen, known by a variety of names among the Early Christians and called the templon or iconostasis by the later Byzantines. The term iconostasis as used today by architectural historians is something of an anachronism in the Early Christian context since the screen in the 5th and 6th centuries was not literally an iconostasis, adorned with painted eikones , or portraits, of Christ, the Virgin, and the saints, nor was it usually tall enough to obstruct the congregations view of the sanctuary and the altar. The typical Early Christian screen was a low parapet, its panels embellished not with portraits but with patterns incorporating the cross and other Christian motifs executed in relief or perforated latticework. Here, in keeping with the available materials and the economy of decoration already observed elsewhere in this Basilica, the screen was constructed of plain blocks of dark blue-gray limestone reused from an ancient monument. Although they may have carried some modest incised decoration like that on the aisle parapet block mentioned earlier, no ornamented surface has survived. Parts of four parapet blocks are still in situ at the eastern end of the nave, two on either side of the central passage through the screen to the bema , together with the stump of a column which marked the northern edge of this passage.

Just behind the screen the bema is paved with stone apparently taken from the same ancient monument plundered for the parapets. Blocks of blue-gray marble are laid in rows alternating with similar blocks of white limestone. On the surface of some pieces are cuttings for the placement of a sculptural group which seems to have included at least one horse; the structure from which they came (now known as the Nu Structure; see pp. 155-57) was perhaps a victory monument dedicated by the winner of an equestrian event at the games some eight hundred years before the construction of the Basilica. If any of the bronze statuary itself still survived when

the base was dismantled, it doubtless went into the furnaces to be melted down along with broken tools, bits of scrap, and clamps pried from the blocks of the Temple, for the Early Christians regarded pagan sculpture with suspicion at best, and metal remained throughout the Middle Ages a scarce and precious material (note the scraps of bronze statuary in museum case 6; see p. 32).

In the center of the bema stood the altar, of which nothing has survived; probably, like most Christian altars of this date in Greece, it was a plain rectangular table of marble supported on four legs or small columns. Behind it, in the apse, where there is no stone paving, was the synthronon . The construction of this part of the Early Christian bema was subject to much regional and individual variation, and its precise form in the Basilica at Nemea is not known.

The roof of the building, as of all Greek basilicas of the 5th and 6th centuries, was made of wood and has consequently perished (except for the hundreds of terracotta tiles which once covered it). There may have been a clerestory above the nave to provide light, but it is perhaps more likely in a Basilica of such restricted means that the only lighting came from windows in the north and south walls, and possibly in the apse as well (as in the basilica on Evangelistria Hill). Tiny fragments of colorless glass which may have come from windowpanes were found in the area during the early excavations.

The main structure of the Basilica was probably built in the late 5th or early 6th century after Christ. Later, though probably not much later, a baptistry was added on the northern side, built up against the north wall of the Basilica and incorporating as part of its west wall the eastern side of the small room north of the narthex. This annex comprised the baptistry proper, to the north, and a narrow room sandwiched between it and the north wall of the church (see Fig. 26). A threshold block in this wall indicates that the narrow room was accessible from the north aisle; presumably it communi-

cated with the rest of the baptistry as well, although no trace of a connecting doorway survives and the northern part of the structure seems to have been provided with an independent outside entrance on the west. The purpose of the narrow room is not clear, but it may have served as a chrismarion or consignatorium , where the ceremony of confirmation and the ritual anointment of newly baptized Christians took place.

The baptistry proper, a rectangular structure ca . 13.00 by 9.50 m., consisted of two parts: an inner chamber, the so-called photisterion (ca . 6.00 m. square), which contained the font; and a corridor (ca . 3.00 m. wide) on three sides of the central chamber. This tetragonal plan with a peripheral corridor is known from other baptistries of the period in Greece, Asia Minor, and elsewhere.[48]

The corridor was paved with terracotta tiles similar in size and appearance to those used in the nave, aisles, and narthex of the Basilica. A low bench ca . 0.45 m. wide once ran along the inside of the outer wall except where interrupted on the west, apparently by a door from the outside. (This door was located just west of the conspicuous round hole in the floor of the western corridor, which is a later medieval intrusion unrelated to the baptistry.)

The photisterion was separated from the corridor on the west, north, and east by a partition wall of unknown height. Traces of benches similar to those which lined the outer wall were found against the western side of this partition, facing the corridor; they may have continued around to the north and east as well. There was certainly a doorway in the western partition wall, opposite the entrance to the baptistry from

the outside, and probably another on the north; for the eastern side evidence is lacking, but another doorway is not precluded.

Within the area enclosed by the partition the remains of two distinct floor levels are visible, both paved with terracotta tiles larger (ca . 0.55 m. square) than those used in the corridor. The earlier pavement is best preserved in the southwestern corner of the chamber; here the tiles are set, like those in the corridor, with their edges more or less parallel to the walls of the building. In the later pavement, visible along the eastern side of the chamber, however, the tiles are laid diagonally. Both pavements are partially preserved in the northwestern corner, where the chronological sequence of the two phases can be made out (the diagonally oriented tries rest on top of the earlier floor). The change may have been prompted by damage to the original paving caused during repairs to the baptistry plumbing.

In the center of the photisterion lies the kolymbethra , or baptismal font, a stepped, sunken basin (ca . 0.40 m. deep) formed of concrete and originally faced with marble. (The large marble slab found in situ in the bottom of the basin was in fact a reused piece of a Christian ritual dining table; see p. 43.) In a later remodeling of the font the two circular steps leading down into the central part of the basin were built up with stone, tile, and concrete approximately to floor level along most of the font's circumference. A circular strip (ca . 0.65 m. wide) was cut back into the tile paving around the font, and the entire area was ringed with low parapet blocks, two of which still remain on the north side. Wastewater from the font flowed through a lead pipe to a drain, built of stone, which ran under the northern corridor of the baptistry and emptied into the more western of the two wells just outside the north wall.[49] (The prominent block with a deep "channel"

[49] The well was out of use by the Early Christian period, but material from its lower levels is displayed on the top shelf of case 9 in the museum; see p. 42.

east of the font should not be mistaken for part of the baptistry plumbing; it is in fact an ancient stele base reused in the eastern partition wall.)

The basin may seem surprisingly small and shallow, but baptism in the Early Christian period was regularly performed not by immersion but by affusion: the catechumen , or newly instructed convert, stood in the font while the officiating cleric poured water over his head from a small vessel.[50] Later, as Christianity grew more pervasive and the baptism of adults more and more infrequent, large independent baptistries like this became obsolete throughout the Christian world. They were replaced by small fonts within the church itself, which proved more convenient for the now-standard practice of infant baptism.

The baptistry, like the Basilica, was covered with a wooden roof, which has perished except for the tiles and a handful of iron nails used in its construction. Fragments of glass in the destruction debris again suggest the presence of glazed windows for lighting, and traces of red and blue pigment found on a small chunk of plaster indicate that here too the walls were stuccoed and painted with bright colors. There is also evidence that the inner face of the screen wall around the photisterion was at least partly decorated with a revetment of green marble, an unexpected touch of luxury in light of the paucity of ornament surviving from the Basilica itself.

The Basilica with its baptistry is the most important architectural monument of the Early Christian period at Nemea, and the only one visible on the site today. It did not stand in isolation, however, as excavation in the surrounding area has shown. Contemporary with the baptistry, or perhaps slightly later, an enclosure was constructed northwest of the Basilica, incorporating on the southeast the corner formed by the west

[50] C. F. Rogers, "Baptism and Christian Archaeology," Studia Biblica et Ecclesiastica 5 (1903) 239-358.

wall of the baptistry and the north wall of the small room north of the narthex. Only small sections of the south and east walls were found during excavation, and the full extent of the enclosure is not known, but it appears to have been an open yard containing, among other things, a cistern and a well (see p. 117), the latter dating back at least to the Hellenistic period but continuing in use, after a long period of abandonment, into the 5th and 6th centuries after Christ.

More substantial were the remains of a large 6th-century house uncovered in the area immediately southwest of the Basilica (Figs. 28 and 29). This complex of rooms, which may represent more than one dwelling, abutted the southwestern corner of the church and extended some 40 m. to the west; other remains of what was probably the same complex were found by excavators in the 1920s in the area between the Bath and the Basilica and above the east room of the Bath itself. The rooms were fairly regular in shape and size at the eastern end but smaller and haphazardly laid out further west, suggesting that the western rooms were later, ad hoc , additions built as the complex expanded outward from its original site close to the church.[51] The walls were constructed of plastered mud brick on a socle of unmortared rubble, the roof was wooden with a covering of clay tiles, and the floors, though occasionally paved with fries or flat stones, more frequently consisted simply of hard-packed earth. The large quantities of coarse household pottery, lamps, fragments of glass goblets, and other similar material recovered from the building leave no doubt about its domestic function, and we may tentatively identify it (or at least part of it) as the residence of the Basilica's clergy. Further excavation below the levels of the Early Christian period has necessitated the re-

[51] In spite of this, the ceramic and numismatic evidence suggests that the entire complex had a compressed history, with construction, occupation, and abandonment all taking place over a few decades in the middle and the second half of the 6th century.

Fig. 28.

Early Christian house walls immediately southwest of the

Basilica, from the southwest.

Fig. 29.

Early Christian house walls south of the Bath, from the east.

moval of these remains, but a narrow baulk of earth supporting part of several rubble foundations is still preserved along the southern scarp of the trench immediately south of the east room of the Bath.

Apart from architectural remains, the Early Christians left their mark on the site in two important ways: by farming the land and by burying their dead around and within the decaying Sanctuary of Zeus. Neither activity was intentionally destructive of ancient monuments, and both were necessary, but the damage they caused has done more to hamper our understanding of the Greek and early Roman periods at Nemea than even the deliberate dismantling of the Temple and other ancient structures for building material.

Agriculture has taken the greatest toll. In fairness to the Christians of the 5th and 6th centuries, however, we should acknowledge that the Christians of the 12th through the 20th century are equally culpable: for over fifteen hundred years the rich soil of the Nemea valley has attracted farmers to whom, understandably, flourishing crops are more important than buried and inedible antiquities. Early Christian farming trenches, which regularly take the form of narrow oblongs laid out in rows (a photograph of a typical plot is on display in the museum; see p. 44), have been found throughout the site, on both sides of the river, except in the immediate vicinity of the Basilica and in the areas set aside as cemeteries. These trenches were dug with stubborn persistence through considerable obstacles and partially eradicated the foundations of many ancient buildings. (The softness which made poros, the light yellow stone often used in foundations, easy to work also made it particularly vulnerable to later destruction. This is clear, for example, from the remains of several oikoi ; see pp. 124-26.) Even where they did not uproot blocks and hack through walls, the Early Christians, with their plows and hoes, churned the distinctly stratified layers of earth from earlier periods into a homogeneous mass, destroy-

ing the archaeologist's most valuable source of information in reconstructing the history of the site.

Over a hundred Early Christian graves have been excavated at Nemea since the 1920s, some widely scattered, others clustered in cemeteries at the northwestern corner of the Temple, along the river between the Temple and the Bath (especially around Circular Structure A), and southeast of the Basilica. The number is uncertain because the similarity of medieval burials and the absence of grave goods make 5th- and 6th-century graves difficult to distinguish from those of the later Byzantine and Frankish periods, especially in contexts disturbed by later agricultural activity. The graves vary from simple earth burials to more elaborate constructions of tile and stone; in the most common Early Christian type the floor and walls of the grave were lined with roof tiles, while additional tiles formed a cover. A characteristic example of a more solidly constructed medieval grave is located near the steps to the Basilica (see p. 78).

The simplicity of these burials and the relative scarcity of personal effects interred with the remains testify once again to the poverty of the Early Christian settlement at Nemea. Most of the graves excavated to date contained nothing but the bones of the deceased; a few have produced rings, small crosses, belt buckles and, in one case, a handful of iron tacks from a pair of hobnail boots, the organic parts of which had long since disintegrated. The large quantity of jewelry and the cosmetic items found in one young woman's grave near the Temple of Zeus (see Fig. 13 and the discussion at museum case 11, p. 45) mark that burial as exceptionally lavish by local standards and suggest that she belonged to an important family in the community.

Although never wealthy, the Early Christian community seems to have been most prosperous in the second half of the 6th century after Christ; numismatic evidence in the excavated area increases for this period, and there are signs of

rapid growth and expansion.[52] Just at this point, however, the settlement was suddenly and completely abandoned: the archaeological record breaks off abruptly, and with the exception of a few stray coins probably dropped by passing travelers, there is no trace of activity on the site for the next five hundred years.

The abandonment is not hard to explain. In the 580s after Christ the defenses of the Isthmos were breached and the Peloponnesos finally overwhelmed by a great influx of Slavic tribes, one of several waves which swept down along the Balkan peninsula from the regions north of the Danube during the 6th and early 7th centuries.[53] Evidence of violent destruction from the nearby sites of Corinth, Kenchreai, Argos, and Halieis (Porto Cheli), along with that from Athens and other sites outside the Peloponnesos, can be firmly dated to the mid-580s; contemporary chroniclers as well as Slavic pottery discovered in the destruction debris at Argos identify the agents of this catastrophe beyond doubt.[54]

At Nemea most of the Christian inhabitants seem to have fled before the invaders arrived. The housing complex southwest of the Basilica showed no signs of violent destruction (in

[52] See preceding note.

[53] The literature on the Avaro-Slavic invasion of Greece is extensive and often bitterly controversial. For recent summaries of the literary and archaeological evidence, together with useful bibliographies, see P. Yannopoulos, "La péné-tration slave à Argos," in Etudes argiennes (BCH suppl. 6: Paris 1980) 323-72; and M. M. Weithmann, Die slavische Bevölkerung auf der griechischen Halbinsel (Beiträge zur Kenntnis Südosteuropas und des Nahen Orients 31: Munich 1978).

fact it apparently stood vacant until the roof fell in from disrepair), but the large quantity of pottery and the many coins left behind suggest a hasty departure. For those who chose not to flee the prospects were grim: a small excavation conducted in 1974 some 500 m. south of the sanctuary uncovered the ruins of another house destroyed at the same date, with the scattered remains of its inhabitants strewn across the floor. No doubt a Christian or Christians from the settlement, fearing the threat of such violence, took refuge in the partly silted-up entrance tunnel oft he Stadium, hoping to hide unnoticed until the danger was past (see museum, p. 47, and Stadium, pp. 188-90).

In some communities disrupted by the Slavic incursions, life continued, if only temporarily and with much-reduced resources. Nemea, however, never recovered. The Slavs did not settle in the vicinity themselves, and the Christian inhabitants who fled and survived apparently made no attempt to return to their homes. The Nemea valley remained deserted for half a millennium.

Renewed human activity on the site began in the 12th and 13th centuries after Christ when another agricultural community grew up among the ruins of the ancient sanctuary. The life of these Byzantine farmers probably differed little

from that of their Early Christian predecessors, and in fact the physical remains of the two communities are similar, consisting largely of plow furrows, irrigation ditches, and the omnipresent graves. Traces of buildings and cisterns have been discovered within the sanctuary, and some rooms added onto the northern side of the Basilica date from this period, although it seems unlikely that much of the old church was refurbished, considering the number of medieval graves found within its walls. The digging of these graves, which range from small private burials to enormous ossuaries, destroyed much of the Basilica's tile paving and must postdate the use of the building as a place of worship.

The site continued to be used, at least as a burial ground, throughout the later Middle Ages. Graves of Frankish and early Turkish date were found south of the mound formed by the dilapidated ruins of the Early Christian Basilica, on top of which, sometime during this period, a small chapel was constructed of ancient material now reused for the second or third time. (This chapel, itself in ruins, remained partly standing as late as the nineteenth century, by which time popular imagination had already labeled the mound the "Tomb of Opheltes"; see Fig. 2.) With the gradual blocking of the outlet of the Nemea River, however, the valley floor became marshy and inhospitable, and once again the site was given over to "the dreary vacancy of death-like solitude" Dodwell (see n. 11) found here in 1805, which prevailed until the restoration of proper drainage in 1883 and the foundation soon after of the modern village of Herakleion, now Archaia Nemea (see p. 10).

The Xenon I

The visitor standing in the 6th-century Basilica simultaneously stands in a building of the 4th century B.C. , one-third of which is covered by the Basilica. Labeled Xenon on the plan

(Fig. 30), this more ancient building probably served as a hotel for some of the athletes and trainers who came to Nemea every two years to compete in the Panhellenic games.

Hotels were ubiquitous in ancient Greece by the 4th century B.C. ,[55] but few scholars have investigated the physical evidence and the written sources which pertain to them.[56] Thucydides—the only ancient author to mention the architecture of a hotel—laconically described one built at Plataia in 426 B.C. as measuring 200 feet on each side with rooms all around, above and below.[57] This description has been interpreted as that of a square building with a central court and has been used to identify some buildings with such a plan as hotels. The building at Nemea, however, differs from Thucydides' description. Rather than being square, the Xenon here is a long, narrow rectangle which clearly lacked a central court. Indeed, for its time, the Xenon's plan was unique. It has been possible, however, to identify it by using criteria of location, plan, and associated finds.

Eating and drinking vessels as well as hearths for cooking found throughout the southern rooms indicate that these rooms were restaurants of a sort; the paucity of such evidence in the northern rooms suggests that they were used for living and sleeping. The plan of the building, which was divided into apartments, with sleeping quarters and dining areas in each, further suggests that it can be identified as a hotel, or xenon . The location of the Xenon, near the Sanctuary of Zeus but outside the Sacred Square, on the major road through the

[55] Buildings to provide temporary shelter for visitors seem to have been typical at the larger sanctuaries of antiquity: at Olympia the Leonidaion and at Epidauros the katagogeion , for example.

[56] Greek hotels are mentioned briefly in general books such as L. Casson, Travel in the Ancient World (Toronto 1974), and specific examples are discussed in some guidebooks to sites or in individual articles. The only complete exploration of the subject is by L. Kraynak, Hostelries of Ancient Greece (Ph.D. diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1984).

[57] Thucydides 3.68.3.

Fig. 30.

Restored plan of the Xenon with outline of the Basilica.

valley, suggests that the structure was secular but played an important role in the business of Nemea; its proximity to the Bath brings it into the realm of athletics. Finally, excavations in Room 12 produced a jumping weight, and strigils have been found elsewhere. Thus this was not only a xenon but specifically a building designed to house the athletes who came from all over the Greek world to compete at Nemea.

The Xenon is visible where it emerges east and west from beneath the remains of the Basilica; it extends for a total of 85 m. A median wall divides the structure longitudinally; latitudinal walls form rooms of varying sizes. The Xenon, like the Temple of Zeus, has parastades , or walls which project into the rooms on either side of the five doorways in the south wall along the main road. Projections like these in the

Temple on either side of the cella door protected delicate moldings from damage, but there was no similar need in the Xenon. The two doorways found in the north wall lack projections like those beside the doors in the south wall. But even though the reason for them remains obscure, the projections serve us well by marking the facade of the Xenon; the building was oriented toward the ancient road, not the sanctuary.

Another odd feature of the Xenon is the row of interior columns in all but one of the northern rooms. Although interior columns per se are common enough, the position of these in the Xenon, some on the longitudinal axis of a room, others south of it, is unusual. Inasmuch as the columns must have served to support weight, and since they occur only in the northern rooms, a second story has been restored over the

Fig. 31.

Perspective drawing of Xenon with restored second story and roofs.

northern part of the building (Fig. 31). The rooms restored above Rooms 5, 10, and 12 have recessed balconies whose back (north) walls are supported directly by the off-center columns of the ground-level rooms. The anomalous shape of Room 7 is due to its use as a stairwell giving access to the second story.

The western end of the Xenon protrudes from below the narthex of the Basilica. Only the foundations of the exterior walls and column bases in Room 2 remain. The median wall of the Xenon protrudes from beneath the nave of the Basilica, crosses the narthex, and continues outside it. In this wall, built of reused blocks of all sizes and shapes, "mortared" with clay, the Aristis inscription now on display in the museum (see p. 37, Fig. 11) was found reused.

Several trenches (now backfilled) have been sunk through the tile pavement of the narthex. At the bottom of one trench the continuation of the median wall of the Xenon is visible

and, north of it, a square column base which is the eastern-most base in Room 2. A coin of Philip II found in this portion of the median wall verified that the Xenon was built in the late 4th century B.C.

The median wall of the Xenon continues uncovered for the entire length of the nave, disappearing into an undug portion before reappearing in the apse of the Basilica. Although the remains of the Xenon within the nave appear chaotic and confusing at first glance, they are worth exploring.

East of the threshold at the entrance to the nave and north of the median Xenon wall are six column bases, one with the stub of a column still in situ (in Room 5 on the plan). Although originally discovered long ago, the record was so sketchy that it could not be understood until old trenches were cleared in 1980. The rediscovery of these column bases was especially welcome because Room 5 had been the only major northern room which seemed to lack interior columns. Moreover, the column stub gives us the type and diameter of the columns in this room, evidence not available for other colonnaded rooms.

A scrappy, poorly constructed wall which crosses the median wall of the Xenon and touches the corner of the second column base from the northwestern corner of the nave represents a second, hastily built, phase of the Xenon, documented elsewhere in the remains. The occasion for it was the brief period around 235 B.C. when Aratos of Sikyon returned the games to Nemea (see museum case 18, pp. 57-58, and n. 35).

The visitor can obtain a closer view of the median wall from the unexcavated strip of. ground along the south side of the nave whence more of the excavated portion of the Xenon is visible. Here, in the corner of Room 4 formed by the median wall and the wall between Rooms 3 and 4, is a round hearth paved with cobblestones. When it was discovered in 1962, a stand like that in House 4 (see p. 76), roughly made of reused roof tiles to support a pot over hot coals, was found

Fig. 32.

Hearth and stand in the northwestern corner of Room 4 of the Xenon

in 1964, from the south. The stand has since been removed.

over the northeastern part of the hearth (Fig. 32). The hearth itself was covered with ashes, several pots (shattered when the roof collapsed), and cow bones (one cleaved by a sharp instrument). Clearly Room 4 was a kitchen. The food prepared there may have been consumed in Room 3, on the other side of the wall from the hearth, where a group of drinking cups and cooking pots was found, pressed into the dirt floor when the wall and roof fell on them.

Beyond the hearth (to the east) another scrappy wall crosses the median wall of the Xenon and disappears into the scarp. The date of this wall corresponds to that of the other poorly built wall near the base of the column in Room 2; it too represents Aratos's short sojourn in Nemea.

The visitor who returns to the south aisle of the Basilica can visit the eastern end of the nave for a view of the apse and

Fig. 33.

The apse of the Basilica, with the eastern end of the Xenon

visible in the background, from the west.

the area beyond it (Fig. 33). The median wall of the Xenon continues into the apse with the threshold between Rooms 6 and 8 and, beside it, another reused block, set in upside down, with the inscription Telestas, a man's name.[58]

After a tour of the rest of the site, we shall return to the eastern end of the Xenon, where the remains allow us to see how the building was constructed. For now, however, we return down the steps from the Basilica to the path, turning right (west) along the path over the ancient road. We leave the path where it turns north toward the Temple of Zeus, striking out westward along the line of a modern road which crosses a bridge over the Nemea River. Just to the right (north) of a large service gate in the fence is the Heroön.

[58] IG IV.486. The letter forms suggest a date in the 5th century B.C. ; the man Telestas whose name is inscribed here should not be confused with the one whose name is scratched on the Stadium tunnel wall (see pp. 36 and 188).

The Heroön

Excavation of the Heroön took place in 1979, 1980, and 1983. The area had been greatly disturbed by agricultural activity in the Early Christian period and later; the effects can still be seen in the foundation stones scarred by plowing.

Three phases of construction can be distinguished in the Heroön: early Archaic, late Archaic, and early Hellenistic.

The Hellenistic Structure

The early Hellenistic phase is the one most visible today (Fig. 34). This latest structure took the shape of a lopsided pentagon, its outline possibly influenced by construction here during the late Archaic period. The south and east walls were set at right angles, more or less, to each other. The north and west walls were set at oblique angles, with a change in direction at the southern end of the west wall.

The north wall is just over 30 m. long and has four buttresses at intervals along its interior face. The east wall was originally 22.35 m. in length, but more than half of it was destroyed long ago by a shift in the course of the Nemea River. Ironically, the southern portion of the east wall is the best-preserved part of the Heroön, with five of the original reddish limestone orthostates still in position. The dimensions of the orthostates average 0.48 by 0.92 m., with a height of about 0.50 m. The south wall, slightly more than 36.50 m. long, has four interior buttresses. The west wall heads north for 4.50 m., then veers northeast for 25.50 m. to join the north wall. There were also four interior buttresses for the west wall.

For the most part, only the foundations of the Hellenistic Heroön are still extant. These are cut from a soft yellow poros, a malleable stone which deteriorates quickly when exposed to the elements. The average foundation block is 0.65

Fig. 34.

Plan of the Heroön, with phases.

by 1.25 m. At fairly regular intervals, blocks made of this same material project inward from the wall foundations, apparently as underpinnings for buttresses or the like. The actual wall above the foundations was no thicker than 0.50 m. to judge from robbing trenches and the next higher course of orthostates preserved at the southeastern corner of the enclosure.

The foundations supported a high fence, probably of stone, rather than a structural wall. The Heroön seems to have been unroofed; no interior roof supports have been found, and such supports would have been needed in such a large building. The structure is also strangely shaped to accommodate conventional roofing. In addition, there is some evidence for

Fig. 35.

Perspective view of the restored Heroön from the northeast.

trees having grown inside the Heroön, so perhaps we should think of a fence surrounding a grassy, sylvan area. Several stone blocks firmly positioned in the open area of the Heroön should perhaps be identified as individual altars (Fig. 35). This matches Pausanias's description of altars and the tomb of Opheltes within the enclosure. The tomb itself might have been a construction northeast of the center of the enclosure. Although now little more than a small, roughly aligned enclosure surrounded by fallen stones, this was once a rectangular structure measuring about 1.40 by 3.15 m. It was erected as part of the late Archaic phase and may have Continued in use dung the 4th century and following, perhaps functioning much as did the so-called Leokorion in the Athenian Agora.[59]

[59] See the description and references given in H. A. Thompson, ed., The Athenian Agora (Athens 1976) 87-90.

The entrance to the Heroön was at the northeastern corner facing the Temple of Zeus, where poorly preserved foundations for a monumental porch or gate stand outside the north wall. Measuring approximately 1.00 by 4.50 m., this porch was perhaps roofed over with curved Lakonian tiles, many small fragments of which were found at this place.

The area of the enclosure seems to have been cleared and leveled for a new construction phase in the late 4th or early 3rd century B. C. Traces of the ritual inauguration of the renovated shrine can be seen in the burial of a pot against the north wall and its easternmost buttress. When excavated, this vessel contained a greasy, dark brown earth. This may once have been the pulse (boiled beans) and vegetables inside what Aristophanes described as installation or dedication pots (see museum case 4, p. 28, and n. 24). The Hellenistic chronology of the Heroön's latest phase makes the enclosure roughly contemporary with the new construction of the Temple of Zeus and the other post-Classical building activity at Nemea.

The Late Archaic Structure

The strange shape of the Hellenistic building may be due to the irregular dimensions of the late Archaic construction since the foundations of this earlier building provided additional support for the 3rd-century structure. This sequence is particularly clear on the western side of the building where the rubble courses of the Archaic phase more or less underlie the Hellenistic ones. The two walls diverge slightly in the southwestern corner, with the earlier wall forming a curve instead of an actual corner (Fig. 36).

Other traces of the late Archaic enclosure have been uncovered beneath and perpendicular to the preserved portion of the Hellenistic east wall near its southern end. The foundations of this enclosure, formed of two courses of unshaped

rough stones, were considerably less formal than those of the later phase. They may have supported a mud-brick wall, protected on top by the tiles found in excavation. As yet no evidence for doors or gates has been uncovered. Although greater chronological precision is not possible, this phase can be dated to the second half of the 6th century B.C.

Inside the late Archaic Heroön was the rectangular structure made of large boulders placed on edge (see p. 106). The large amounts of ash, bone, and apparently votive deposits associated with this structure suggest cult activity—possibly an altar or, as already suggested, the tomb of Opheltes.[60]

The Early Archaic Structure

Remains of a yet earlier Archaic phase (in the first half of the 6th century B.C. ) can best be seen in the southwestern comer of the enclosure, where stone foundations of ashlar masonry are cut by, and therefore predate, the curvilinear rubble wall of late Archaic construction. Other features that may be connected with this phase lie further north along the west wall. A jumbled mass of rocks near the midpoint of the wall may have been left over from the dismantling of the early wall, then used as packing for later landscaping. More of these large unworked stones lie under the northwestern corner of the Heroön.

There is a sharp contrast between the cut poros foundation blocks from the southwestern comer and the unaligned, unworked stones to the north. What sort of activity took place here during the early Archaic period? Were there two different structures? Was the same function involved? The present

[60] This is not to say that an actual burial was located here; rather, it was a legendary one; no evidence of human burial has been uncovered at the Heroön. Such cenotaphs were common in antiquity, e.g., the "Tomb of Achilles" at Elis attested by Pausanias 6.23.3 and 24.1.

Fig. 36.

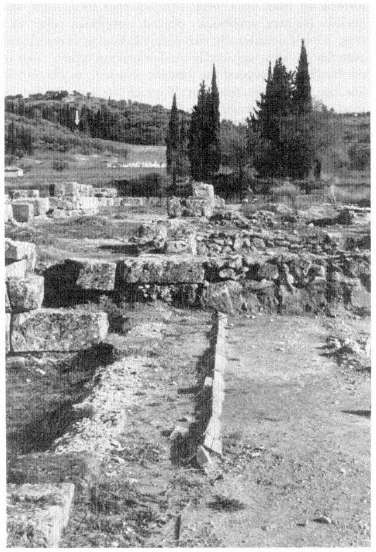

Aerial view of the Heroön, 1980.

state of the evidence does not allow us to answer these questions easily.

The early Archaic phase can be dated to the first half of the 6th century, around the time traditionally given for the establishment of Nemea as a site for Panhellenic athletic contests. Apparently the earliest "Heroön" had been in existence for about fifty years when the late Archaic enclosure was constructed.

Pausanias described the Heroön of Opheltes near the Temple of Zeus at Nemea as a

surrounding the tomb of the child. He used this particular phrase in four other instances, including his accounts of the shrines of Ino-Leukothea at Megara and of Pelops at Olympia.[61] The Pelopion has been excavated, and the information thus gained has been useful in reconstructing the Heroön at Nemea.[62] The function of the two structures, after all, was the same: to monumentalize and sanctify the tomb of a dead hero.

The identification of this area as the hero shrine of Opheltes has already been discussed (pp. 27-29). Although the Pelopion at Olympia occupies a central location in the sanctuary near the Temple of Zeus, here at Nemea the shrine to the hero whose mythical death is central to the foundation story of the games lies on the periphery of the Sanctuary of Zeus. The topography thus illustrates and emphasizes the extent to which Zeus dominated the games, the sanctuary, and the baby-hero. Nonetheless, the scale of the Heroin and the quantity of the dedications discovered within it show that the cult of Opheltes enjoyed a fair popularity.

The Bath

Returning to the flagstone path, we notice the southwestern corner of the Xenon to our right; south of it and along the edge of a gravel surface of the ancient road runs a section of the terracotta aqueduct which brought water to the Bath. This simple aqueduct was constructed of U-shaped tiles, curvilinear inside, rectilinear outside. Covering the channel

[61] See Pausanias 2.15.3 for his description of the Heroön at Nemea; 1.42.8 for Ino-Leukothea; 5.13-1 for Pelops. Further comparison of these sites is invited by similarities in myth. Ino-Leukothea is identified as the mother of Melikertes-Palaimon, the hero of the Isthmian Games. The other two sites are also chthonic sanctuaries, i.e., the sanctuary of Chthonia at Hermione (2.35) and the sanctuary of the Mistress near Akakesion (8.37).

[62] See A. Mallwitz, Olympia und seine Bauten (Munich 1972) 133-38.

formed by these tiles were ordinary roof tiles, most frequently (as here) rectilinear, peaked Corinthian cover tiles (Fig. 37) but occasionally curvilinear Lakonian cover tiles or even flat pan tiles, apparently used in making repairs. East of the Basilica and beyond the modem cemetery, in the middle distance, is a ravine the floor of which has been leveled by modem agricultural activities. To the right (south) of this is a large modern reservoir and immediately beside it a Turkish fountain house (Fig. 37, at arrow). At one time these were fed, like the aqueduct for the Bath in its time, by a copious spring near the head of the ravine. That spring was tapped by a tunnel with a vaulted ceiling cut back some 16.40 m. into the bedrock (Fig. 38). Although its date has not been established, this tunnel would have been appropriate to the creation of the Bath.

From the flagstone path, with the Xenon to the east and the Bath to the west, we can see that the two structures are precisely the same width and have the same alignment. These similarities suggest that they were a part of the same building program, and excavations have shown that the aqueduct for the Bath is only slightly later than the Xenon.

Visitors enter the Bath by way of the large East Room (nearly 20 m. square) in the center of which are the foundations for four interior roof supports which form a smaller square (Fig. 39). The southeastern foundation retains its base (a large weathered gray block); the other foundations are preserved only far below the level of the original floor. During the Early Christian period this area was dug down some 0.40 m. below the level of the original floor; for this reason no evidence for the location of ancient doors has survived.

The West Room of the building consists of another large space divided into three east-west aisles by two rows of columns. In the northern row four of the five original bases remain; the central one was destroyed when the Nemea River forced its way through the building in early modem times.

Fig. 37.

The aqueduct from the west, with Corinthian cover tiles in the foreground;

the arrow shows the region of the spring on the eastern side of the valley.

Fig. 38.

View of the rock-cut tunnel for the spring.

Fig. 39.

Restored plan of the Bath.

The rerouting of the river to its present course (very close to its ancient bed) took place only in 1924, after the Bath had been discovered.

The south aisle of the West Room is actually a sunken bathing chamber. The columns dividing it from the rest of the room (the bases of only the three furthest east are now visible) are actually projections from the line of the wall marking the limits of this bathing chamber. This chamber is approached from the middle aisle of the West Room through the intercolumniations to the right and left of the center column, beyond which a broad staircase leads downward. The Doric capital in the museum courtyard (A 7; see p. 73), discovered at the western end of this staircase, provides important details for the reconstruction of the interior colonnade. The intercolumniations flanking the two at the center were blocked by a parapet over the sunken chamber to prevent accidents; several blocks of that parapet have been reerected in something like their original positions.

The bathing chamber is itself divided into three parts, all of which exhibit heavy coats (in some areas two layers thick) of hydraulic cement. The wide Central Pool is separated from the smaller flanking rooms by a wall which was about chest high originally, as is indicated by a socket cut into the south wall (Fig. 40). The flanking rooms are virtual mirror images of one another. Each was entered by the side steps of the staircase, and each is equipped with four stone tubs placed end to end along its rear wall. These tubs were fed by a stone water channel set back into the wall; it was pierced at appropriate intervals by holes through which the water flowed into the individual tubs.

Although two tubs have V-shaped notches in their sides for overflow, none of the tubs is equipped with an outlet. Notches cut at the top of their common walls allowed water to flow from one tub to another. Wastewater in the East Tub Room flowed across the floor to an opening at the corner of the staircase. A terracotta channel under the staircase, behind its

Fig. 40.

View of the bathing chamber from the north.

first step, carried the water to the opposite corner of the staircase, where it simply flowed out over the floor of the West Tub Room to a hole beneath the northernmost tub. This, in turn, connected with the Nemea River. Wastewater from the West Tub Room itself flowed to the same hole, whereas that of the Central Pool ran into a hole at its own northwestern corner to join the channel beneath the staircase; from there it flowed through the same system as the wastewater of the East Tub Room. For the wastewater system to work, the floors of the rooms had to be progressively lower toward the west.[63]

A hole in the south, or back, wall of the Central Pool marks the entry point for its water; its height shows that the water in this pool would have been about chest high or slightly lower and that the pool itself was intended as a plunge bath. The tubs in the flanking rooms were too shallow and short to

[63] The hole at the base of the north wall of the West Tub Room and the cement channel set into the ancient floor leading to it are not ancient but were created in 1958 by N. Verdelis of the Archaeological Service.

Fig. 41.

Restored perspective of the bathing chamber.

be individual bathing tubs. Ancient representations show clearly that they were meant to be used as basins from which to splash or throw water on the body (Fig. 41).

Parts of the reservoir system that supplied water are visible from the southwestern corner of the East Room. These would have been fed by the aqueduct, but the remains at the point of connection have been obliterated. Nonetheless, the general workings are clear. Two long narrow reservoirs, originally about 1.00 m. deep and 0.60 m. wide, run alongside the exterior south wall of the building. The one closer to the building is interrupted just at the southeastern comer of the East Tub Room where a smaller tank, a 0.60 m. square "water closet," is formed. Both the larger and the smaller reservoirs served only the East Tub Room, and the existence of the water closet shows that the flow of water was not constant but rather was regulated by periodic flushings of the water closet.

The reservoir west of the water closet and the entire southern reservoir served the Central Pool and the West Tub Room. Whereas probably the pool was completely filled and emptied at intervals of several days, the West Tub Room would have been regulated in the same manner as the East Tub Room. Unfortunately the reservoirs west of the inlet to the Central Pool are not preserved, so that the details of operation are not certain.

The Bath, firmly dated to the last third of the 4th century B.C. , is one of the earliest bathing systems known in the Greek world. More difficult than dating, however, is the assignment of a precise ancient name. At an athletic center like Nemea we would expect a palaistra-gymnasion complex, and the palaistrai of Delphi and Olympia, to cite the most relevant examples, were equipped with bathing facilities.[64] They seem, however, to be a generation or so later than the example at Nemea. Moreover, the Nemea structure, although sizable, does not have all the subsidiary rooms (for boxing, oiling, etc.) we expect in a palaistra , nor does it have the practice running tracks, approximately 200 m. long, always found in a gymnasion . At Delphi and Olympia such tracks are obviously present, but at Nemea there is no space available for them in association with the Bath.

Without evidence for the ancient name,[65] it seems best to refer to the building as a bath and to leave open questions about the restriction of its use to athletes.[66]

The Oikoi I

To the right of the flagstone path, north of the Xenon and the Bath, is a large square block, reused in the Early Christian period as a wellhead (see p. 90). Discovered broken into four

[64] See Mallwitz, op. cit . (n. 62) 278-89 for the palaistra-gymnasion complex at Olympia, and J. Jannoray, Foullies de Delphes , II, Le Gymnase (Paris 1953) for Delphi. Very recent excavations in the xystos , or covered race track, in the Delphi gymnasion have revealed more of its features and parts of a victors' list of the Roman era; see BCH , Chronique 111 (1987) 609-12.

[65] The circular altar dedicated to "Zeus in the Grain Office" (I 9 in the museum courtyard; see p. 72 and n. 40) was perhaps discovered immediately south of the Bath. It is difficult to see any connection between the Bath and a grain office—whatever that might be.

[66] For bathing establishments and customs in the Greek world see R. Ginouvès, Balaneutiké (Paris 1962). Although Ginouvès's subject goes beyond that of this survey, none of the examples he collected serves as a precise architectural parallel for the Nemea Bath.

pieces and thrown down the well, the head has been mended and reestablished in its original position (although it had an even earlier life, as shown by the anathyrosis on its sides). At each corner of its upper surface shallow depressions show where vessels were placed while water was fetched. The well, which extends slightly more than 10 m. below this stone head, may originally have served Oikos 1, which lies directly north (Fig. 42).

The scanty remains of two walls east and south of the well may have formed part of a back room for Oikos 1 by analogy with the rooms behind Oikoi 8 and 9 (see pp. 165-67). Beyond these walls, extending under the northwestern corner of the baptistry of the Basilica, was a pit filled with marble working chips and tools (see museum case 20) used to manufacture the sima for the Temple of Zeus in the later 4th century B.C.

Oikos 1 (across the path from a circular foundation to which we shall return) is the first of the nine oikoi which extend eastward from the flagstone path.

Oikoi is the plural form of the Greek word oikos , meaning "house" but also used to denote tent, room, chamber, estate, and birdcage.[67] As an architectural unit an oikos has no fixed features; the word is used generally to describe a building set up within a sanctuary by a city-state. Although the precise use of the building is uncertain, it may have served more than one purpose—as a combined treasury and meeting hall, for example. Although the first oikos in the series at Nemea was discovered in the 1920s and the first two oikoi as well as the northwestern corner of the third were explored in 1964, the buildings were not identified as oikoi until the whole series was uncovered during the 1970s. At that time it was possible to see that they formed a unit related to this site as the treasuries of Olympia were related to theirs.[68] The Nemean oikoi , like the treasuries at Olympia, are similar buildings in a line

[68] See Mallwitz, op. cit . (n. 62.), 163-79.

Fig. 42.

Plan of the row of oikoi

defining one boundary of the sacred area of the sanctuary. Simple architecturally, the oikoi , like the Olympian treasuries, were meant to be impressive only from the front facing the square, in this orientation proclaiming to visitors the wealth of the city-state which had erected each one. Thus it is tempting to connect two reused blocks found in 1964, one in-scribed "of the Rhodians" (I 105 see p. 70) and the other "of the Epidaurians" (I 31; see pp. 71 and 169), with the oikoi and to suggest that they identified one oikos as that of the Rhodians, another as that of the Epidaurians.

Despite their similarities to the Olympian treasuries, the Nemean oikoi are much larger (at least four of the Nemean oikoi are larger than the largest Olympian treasury). In addition, no dedications (which one would expect to find in a treasury) survive in connection with the Nemean oikoi , perhaps because the buildings are poorly preserved, extensive farming activity in the Early Christian period having obliterated the floor levels of many of them. Perhaps a closer analogy can be made with the oikoi at Delos, a series of buildings, comparable in size to those at Nemea, which lie along a curve at the northern boundary of the sanctuary of Apollo.[69] These

[69] The size of the Nemean oikoi and the absence of a prodromos , or ante-chamber, which is a part of the Delian oikoi , of the majority of the Delphian treasuries, and of the Olympian treasuries, may suggest the form of a large, simple lesche. See J. Pouilloux, Foullies de Delphes , II, Topographie et Architecture, La region nord du sanctuaire (Paris 1960) 132, n. 3.

buildings, which may have been used for meetings and ritual banquets,[70] housed offerings and diverse material, including, according to the inventory inscriptions cataloguing their contents, libation bowls, iron anchors, bronze pins, tripods, oak timber, bronze lamps, incense, bronze rams' horns, ships' beams, and all varieties of pottery.[71] Thus it might be appropriate to think of the Nemean oikoi as storerooms, embassies, or meeting halls and not simply as treasuries. In fact, although there is only comparative evidence that the Nemean oikoi were used as treasuries, there is positive evidence that they had some unique uses, which will be discussed as we consider each building individually.

Because the oikoi are poorly preserved, their history cannot be easily traced. Oikoi 4, 5, and 6 were constructed in the first half of the 5th century B.C. , and although Oikoi 2 and 3 cannot be definitely dated, there is no evidence that they could not also have been constructed at that time. Moreover, since Oikoi 2 through 6 are built on the same level and planned with roughly the same dimensions, it seems probable that they were constructed at the same time. Oikoi 1 and 7, unlike the others, are slightly out of alignment; their deviation—one slants to the southeast, the other to the southwest—may only reflect the importance of the facade: the buildings were perhaps not meant to be scrutinized from various vantage points. Therefore we can probably assume that the oikoi were all built at roughly the same time in the first half of the 5th century B.C. There is evidence that many of them were either destroyed or had been remodeled by the late 4th century B.C. Those which survived were robbed out by later inhabitants of the site, and all suffered extensive damage from farming activity.

[70] For more on oikoi see P. Bruneau and J. Ducat, Guide de Délos (Paris 1983) 120.

[71] See, e.g., Inscriptions de Délos (Paris 1926) nos. 180, 296, 298, 300, and 442.

Oikos 1

The largest of the series, Oikos 1 measures 22.40 by 13.15 m. (on average). Its floor level has been lost because of the extensive farming by Early Christians in this area, and the building is preserved almost exclusively in its soft yellow poros foundations, which are themselves often missing or eroding because of exposure. When the building was in use, these blocks would not have been exposed to the air. The entire foundation of the south wall is missing except for one block in the southwestern corner which allows us to establish the dimensions of the building. The only blocks preserved above the foundations are those at the northeastern comer, the eastern interior base visible just east of the center of the oikos , and the remnants of a second base 2.00 m. west of the first. These two column bases could have efficiently supported the entire roof. Although no other oikos has this exact plan, the oikoi are all of a type: a simple rectangular shape, with roof supports sufficient for the size of the building provided where necessary.

In 1977 the area west of Oikos 1 was explored to uncover any further oikoi in this direction. Although no further buildings were uncovered, the area was found to consist of compact layers of earth, suggesting the existence of an ancient path to the Temple beside Oikos 1, roughly in line with the modem flagstone path.

Beyond the west wall of Oikos 1 lies a curious row of unworked stones set into the earth. Each stone is pierced by a hole formed naturally when water eroded away the larger stones Of the conglomerate rock. The stones seem to have been chosen because of these holes and placed so that the holes were just above ground level. They are level with the top of the poros foundations and are all perpendicular to the west wall. Only six stones remain in situ , although seventeen were noted during the 1926 excavations, including one cylindrical

worked poros stone. No satisfactory explanation of their function has been offered; perhaps they were used to hold ropes used as anchors or tethers. Subsequent excavations uncovered similar stones in several other oikoi .

North of the north wall of Oikos 1, two more inset stones are visible, the one further west pierced like the others, the one further east unpierced. These stones flank the area of the main doorway, evidenced by a second foundation block representing a threshold abutting the southern side of the north wall, visible south of and in line with the unpierced stone. The size and nature of this entrance cannot be precisely determined because an Early Christian grave cuts through this southern block and its immediate neighbors in the north wall.

Oikos 2

The northern foundations of Oikos 2, east of Oikos 1, consist of a double rather than a single row of poros stones. Although nothing remains above them, the extra reinforcement indicates that they supported a heavy and ornate facade which faced onto the Sacred Square. Moreover, the northern foundations of Oikos 2 protrude slightly beyond the line of the side walls, and the building narrows 0.20 m. from north to south, further emphasizing its northern orientation. It seems likely that the purpose of the double-width foundation and its extension beyond the side walls was to accommodate the krepidoma , or three-stepped platform, of a columnar or pseudo-columnar facade, with setbacks for one or two steps. The similar doubling of the northern foundations on Oikoi 3, 4, and 7 indicates that these oikoi probably had similarly ornate facades. An example of this sort of facade is shown in the reconstructed drawing of Oikos 9, whose northern foundation was similarly doubled and extended but whose facade was reconstructed based on more specific evidence (see Fig. 60, p. 165). Oikoi 1, 5, and 6 probably had simple facades since they do not have a double northern foundation.

Fig. 43.

Interior column base with pierced stones in Oikos 2, from the north.

The two interior column bases for Oikos 2 can be seen along its north-south axis. The northern base rests partly on a reused hard limestone euthynteria , or leveling course, block to the north and a poros block to the south. The surface of the euthynteria block has been worked down in the southern center section to receive the base, and the block still shows a well-preserved molding on its northern edge. Another poros stone to the south, flanking the poros stone on which the base partially rests, serves no apparent function in the present arrangement. The northern base appears originally to have been 0.50 m. further south; if this is the case, the bases would have been equidistant from each other and from the north and south walls.

Four more of the naturally pierced stones observed along the west wall of Oikos 1 can be seen in a line between the two interior bases of Oikos 2 (Fig. 43), and a fifth is visible just south of the southern base. The holes piercing these stones

are not oriented uniformly like those of the stones along Oikos 1; instead, some are parallel to the walls, some perpendicular to them. These stones can be positively associated with the occupation of the building; any explanation of their function and that of the stones along Oikos 1 must be plausible in both an indoor and an outdoor context.

Oikos 3

The most striking feature of Oikos 3 is the trench, dug in the 1920s, which runs through the center of the building along its north-south axis. Part of the northwestern corner of this oikos is also cut by a 1964 trench, visible in the northeastern corner of Oikos 2. Nothing remains above the foundations of Oikos 3, and there are no traces of its interior supports or its south wall. The protrusion of the facade foundations beyond the side walls is more pronounced in Oikos 3 than in Oikos 2, but in general this badly damaged oikos is similar to Oikos 2. The east wall of Oikos 2 and the facing west wall of Oikos 3 show that the buildings are aligned with each other.

Oikos 4

The next oikos to the east, Oikos 4, was a building with colonnades on all four sides. The fragmented remains of four column-support bases approximately 3.50 m. apart on centers can be seen in place of east and west walls. The base in the southwestern corner is the best preserved; from it the approximate dimensions of 1.20 by 1.00 m. for the bases are obtained. A few stone fragments midway between the remains of this block and those of its western counterpart may represent a center column-support base. If so, it would establish the southern boundary of the building. The hard. limestone block south of the southeastern base does not appear to be part of this structure. Three more of the naturally pierced

stones can be seen between the southeastern and central bases, all with holes oriented east-west and none definitely associated with the occupation of the building. One hard limestone block at the western end of the facade lies lengthwise abutting the double row of poros blocks; it is not answered by a similar block on the eastern end. This block may indicate the need for added reinforcement at this point. The square area cut down to a lower level in the northeastern corner of this oikos is the remnant of a 1920s trench.

Oikos 5

East of Oikos 4, Oikos 5 is one of the best-preserved oikoi despite the robbing out of its north wall, perhaps late in the 4th century B.C. The rest of the foundations are well preserved except for those in the southeastern corner, where a Byzantine pit cuts through both these foundations and a large section of those in the southwestern comer of Oikos 6. A 1920s trench also cuts through the northeastern section of the building, just inside the east wall. The rubble socle of the upper wall can still be seen atop the southern and southwestern foundations. Midway along the south wall are two adjacent reused limestone blocks larger than those elsewhere in the rubble of the upper wall. The western block displays a dowel cutting in the center of its upper surface and a posthole cutting for a doorpost in its northwestern corner, both from its previous context; the eastern block has a pair of "ice-tong" lifting holes from its previous use in the Early Temple. A shallow ledge cut into the rocks approximately 0.10 m. from the edge runs along the western and northern sides of the western block and the northern and eastern sides of the eastern block. These cuttings for a doorstop and pivot hole show that these blocks, as reused, formed the threshold of a single-leaved door approximately 0.95 m. wide. This door dates from a period later than that of the original construction of

the oikos , probably the late 5th or early 4th century B.C. , as indicated by the stratigraphy south of the doorway.

Of the two interior bases in Oikos 5, the southern one (0.75 by 0.85 m.) is more than twice the size of the small northern one (0.50 by 0.55 m.). The great distance (8.70 m.) between these bases relative to the 16.10 m. overall north-south length of the oikos implies that a third base was located between the existing two. Just to the west, along the same axis as these bases, are seventeen pierced stones similar to those found in or near the other oikoi . Here the stones can definitely be associated with the period when the oikos was occupied. The holes in the stones have no apparent consistent or meaningful orientation, and the number of holes in each stone varies, some having two or three but most having one, 0.03 or 0.04 m. in diameter. The reddish pigment in several of these stones may be related to their function but may also be due to natural causes.