The Decline of the Older Cities

New York, Jersey City, Hoboken, and most of the region's other older cities derived their initial developmental advantages from their locations along the waterfront. During the nineteenth century, the major economic activities of the New York region were clustered around the port. The rudimentary transportation system compelled most people to live near their places of work. As a consequence, the inner neighborhoods of the older cities were intensively developed, with residential densities reaching 300,000 per square mile in lower Manhattan. As long as economic and technological factors required the concentration of industrial, residential, and commercial activities in and around the port, the older cities thrived. Between 1850 and 1910, Manhattan's population more than quadrupled (from 516,000 to 2.3 million) while that of Brooklyn soared from 139,000 to 1.6 million. During the same period, Newark grew from a town of 40,000 to a city of 347,000; and Jersey City was transformed from a small port of 7,000 into the region's most important rail terminus with a population of 268,000.

For more than sixty years, however, the economic, technological, social, and political tides have been running against the older cities. Many of the advantages the intensively developed cities enjoyed during the age of steam have become liabilities in the era of the internal combustion engine. Like the inner districts of metropolitan areas across the nation, New York's older cities have been losing both people and jobs to the suburbs, particularly in the years since World War II.

In the late nineteenth century, improvements in the transportation system began to free residential development from its ties to the inner section of the New York region. Subway construction in New York City began in 1900; within a decade Manhattan's teeming lower east side was losing population. By 1920, overcrowded Manhattan itself registered an absolute decline. Decentralization was speeded in the 1920s as automobile usage increased rapidly, coupled with the growth of a regional highway network which spanned the major water barriers. In 1920, 72 percent of the 22-county region's population lived in the core. By 1950, the core's share had dropped to 63 percent. During these three decades, the population losses in the older sections of the core were balanced by continued growth in the cities' outer neighborhoods. As a result, the core as a whole gained 1.4 million residents between 1920 and

1930. By the 1940s, however, the core's rate of growth was less than a fifth of that of the suburbs.

During the 1950s, these trends rapidly accelerated. Five of the region's seven largest cities failed to grow. New York City lost 110,000 residents during the decade; and in the three oldest boroughs—Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx—the decline totaled close to 400,000. Across the river in crowded Hudson County, which had been losing residents steadily since 1930, all but two of the county's twelve municipalities declined. During the 1950s, the core lost 210,000 residents while the suburbs were gaining 2.4 million. By 1980, the population of the core had declined to 7.6 million, and accounted for only 40 percent of the inhabitants of the 31-county region. These figures are shown in Table 6.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Departure of Middle-Class Whites

Underlying postwar population change in the core has been the massive exodus of white families from the region's older cities. Throughout the twentieth century, the outward flow from the older neighborhoods has been composed primarily of white middle-class families with children in search of more space, better schools, fresh air, and "the good life." In recent years, rapidly rising wages for skilled workers have combined with the decentralization of manufacturing to add large numbers of middle-income blue-collar workers to the ranks of those moving outward. Except for sprawling Queens, which gained 340,000 inhabitants between 1950 and 1980, little land has been available in the core for single-family housing or garden apartments. The more attractive housing in the older cities tends to be too expensive or too cramped for middle-income families with children. But most of the core's available housing is obsolete, deteriorating, and located in crime-ridden neighborhoods. Also, city schools suffer by comparison with those in most suburbs. Nor can the crowded neighborhoods of the older cities compete effectively with the suburbs in the provision of play space for children, recreational opportunities for the entire family, or off-street parking facilities for the ubiquitous automobile. For the citizen interested in influencing local school, tax, or land-use policies, the small-scale governments of suburbia appear to offer greater opportunities for effective participation than the massive, inertial bureaucratic system of New York City, or the machine politics of places such as Jersey City.

For these and other reasons hardly unique to the New York region—not

the least of which is the fact that the postwar version of the American dream for most has been a suburban dream—the core experienced a net decrease of 1.25 million whites between 1950 and 1970, as shown in Table 7. These data, however, understate the total number of whites who actually left the core, since natural increase (births minus deaths) compensated for some of the out-migration. The vast majority of the whites who deserted the core settled in one of the region's 500-odd suburbs, which added 3.8 million whites to their population during the 1950s and 1960s.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In recent years, these general trends have been slowed in a few core neighborhoods. Rapidly rising housing costs in the suburbs have increased the attractiveness for some whites of older housing in parts of the core. Changing life styles—which have dramatically increased the number of single individuals and childless couples—have decreased the importance of schools for many younger white adults, and thus enhanced the attractiveness of housing bargains and convenient locations in sections such as Cobble Hill in Brooklyn and Hoboken in Hudson County. But these developments have affected overall population trends only slightly. Between 1970 and 1975, 700,000 more whites left New York City than moved in, and the net loss of white residents was more than 450,000.

The Growth of Black and Hispanic Ghettos

Most of the whites who left the core during the past quarter-century were replaced by blacks or Hispanics. In comparison with other large metropolitan areas, the most striking feature of this influx has been the number of Hispanics, primarily Puerto Ricans, who accounted for 21 percent of the population of the core in 1980. Between 1950 and 1980, the core's Hispanic population increased more than sevenfold to nearly 1.6 million, with substantial numbers of Cubans, Dominicans, and other Latin Americans joining Puerto Ricans in the older neighborhoods of the region's core. Over the same three decades, the black population more than doubled, from 876,000 in 1950 to 2.0 million in 1980.[14] Each of the core's six components shared in this massive influx. (See Table 8.) By 1980, Brooklyn had the largest number of blacks, while the largest concentration was in Newark, where 58 percent of the population was black and 18 percent Hispanic. Altogether blacks and

[14] Census data for 1980 enumerated blacks of Hispanic origin in both categories.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hispanics accounted for more than 40 percent of the population of the core by 1980.

Like the earlier immigrants, most blacks and Hispanics arrive in the New York region poor and unskilled. As their predecessors did, they occupy the region's oldest and least desirable housing. Since most of this housing is in the core, these groups are captives of the decaying neighborhoods of the older cities. In 1970, 73 percent of the region's 2.6 million nonwhites and 87 percent of its 993,000 Puerto Ricans lived in the core. To date, relatively few of these newcomers have had sufficient income to follow the trail of the earlier immigrants, who have moved out from the slums and obsolete gray areas of the core. Those having the income to command better housing in the outer neighborhoods of the cities or in suburbia must contend with ethnic and, more important, racial prejudice, which is reinforced by the policies of local banks, real estate brokers, suburban governments, and school boards.

For the blacks and Puerto Ricans, as for the Irish, Italians, and Jews before them, New York was the land of opportunity. As Harlem-born Claude Brown puts it: "These migrants were told that unlimited opportunities for prosperity existed in New York and that there was no 'color problem' there. They were told that Negroes lived in houses with bathrooms, electricity, running water, and indoor toilets. To them, this was the 'promised land' that Mammy had been singing about in the cotton fields for many years."[15] But in New York, as in every metropolitan area, the promised land turned out to be a squalid slum in a segregated ghetto of a racially divided metropolis.

Central Harlem is the core's oldest black ghetto; but it differs little from the region's other concentrations of low-income blacks and Hispanics, such as East Harlem and the lower east side in Manhattan, Morrisania in the Bronx, Bedford-Stuyvesant and Brownsville in Brooklyn, Corona in Queens, or Newark's central ward. Almost all of central Harlem's 80,000-odd residents are black. More than half of its housing is deteriorated or dilapidated. The unemployment rate is twice that of the rest of New York City. Family income is one-third that of the rest of New York City. Children are disadvantaged at every turn in Harlem and the core's other ghettos. Harlem's infant mortality rate is almost twice that of New York City as a whole. The lack of recreational areas other than the streets helps account for the fact that children in Harlem

[15] Claude Brown, Manchild in the Promised Land (New York, Macmillan, 1965), p. 7.

are far more likely to be killed by automobiles than elsewhere in the city. Almost all of Central Harlem's school-age children attend de facto segregated schools, where, as Kenneth Clark shows, "the basic story . . . is one of inefficiency, inferiority, and massive deterioration. The further these students progress in school, the larger the proportion who are retarded and the greater is the discrepancy between their achievement and the achievement of other children in the city."16

The Dispersal of Blue-Collar Jobs

Adding to the plight of the newcomers has been the steady erosion of employment opportunities in the core for those lacking education and white-collar skills. Except for the small minority with the talents in demand in the CBD, the job prospects for blacks and Puerto Ricans in the older cities have grown progressively worse in the postwar years. Between 1947 and 1976, factory jobs in New York City were more than halved, dropping from 1.12 million to 543,000. In 1975 alone, the city lost 65,200 blue-collar jobs.

Jobs, like people, have been leaving the inner sections of the New York region for a long time. Economic and technological changes have slowly eroded the competitive position of large portions of the core. Before the advent of the railroads, the island of Manhattan was a highly preferred industrial location, as entrepreneurs sought to gain the advantage of cheap water transportation. This comparative advantage disappeared because most of the railroads serving the region stopped at the west side of the Hudson. As a result, as Vernon points out, "plants with major freight-moving requirements . . . increasingly [favored] the New Jersey side of the Region. At first, this preference retarded growth in Manhattan only, but later its effects were felt in Brooklyn and Queens as well."17 By freeing many industrial operations from their dependence on the railroads, the development of the truck and the public highway speeded the decentralization of manufacturing operations in the region.

Equally important in pushing industry out from the intensively developed sections of the core has been industry's quest for space. By the end of the nineteenth century, most of the region's noxious industries had left their original locations in Manhattan. The slaughterhouses, chemical plants, and refineries sought space for their operations and wastes in less-developed parts of the core and beyond, in areas such as Brooklyn's Newton Creek, Hunts Point in the Bronx, the Jersey Meadows, and the shores of the waterway separating Staten Island and New Jersey. Manufacturers, particularly those with large plants and growing employment, joined the exodus in the twentieth century.

Space and transportation also underlie the postwar decentralization of industry. Modern industrial processes require large tracts of land that are extremely difficult to assemble in the crowded core with its rectangular street grid and small blocks. Unable to adapt its Manhattan plant to modern continuous flow operations, the National Biscuit Company moved to Fair Lawn, New Jersey, where it built a quarter-mile-long automatic bakery. Another rea-

[16] Kenneth B. Clark, Dark Ghetto (New York, Harper & Row, 1965), pp. 119–120.

[17] Vernon, Metropolis 1985, p. 38.

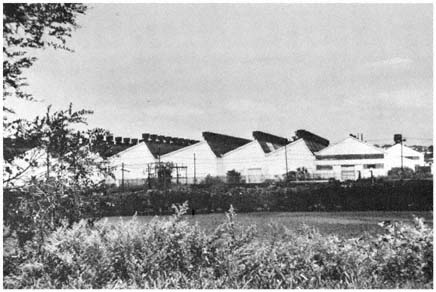

The increasing space requirements of

industry moved factories outward from the

center, initially along the region's waterways,

as in the case of this large plant located

near Newark. Credit: Michael N. Danielson

son Nabisco left the city was the heavy toll placed on its distribution operations by traffic congestion on the narrow streets of lower Manhattan. Lack of room for expansion, the inadequacy of city factories and lofts for modern operations, and the high costs of congestion also push much smaller concerns out of the core. Typical is the paper jobbing firm that left an old four-story building in Brooklyn for an industrial park in Syosset where a modern conveyor system could be employed; or the paint wholesaler who would not have abandoned Brooklyn for Farmingdale "if we had had a plant in New York with adequate facilities for future expansion . . . and where we wouldn't have had to fight traffic and parking problems every day . . . "[18]

Many of the industries that remain in the core's older manufacturing districts are small firms reliant on external economies. Of the factories remaining in New York City, two-thirds employ fewer than twenty people. Most of these small firms depend on outside contractors and suppliers. These small, frequently marginal, concerns also are attracted to the core by the cheap space available in the loft districts and the new low-wage labor pool provided by the spreading ghettos. As Schlivek observes, "the arrival of the latest group of newcomers—and especially the women among them—has acted as a brake to slow down [the flight of industry]. If they were not here to supply a cheap bank of labor it is unlikely that many of the more routine jobs still carried on in the city, e.g., the assembling of electrical fixtures, toys, and

[18] Emanuel Cantor, president of Cantor Brothers, Inc., quoted in Dudley Dalton, "Space Not Taxes, Prompts Moves," New York Times, August 9, 1964.

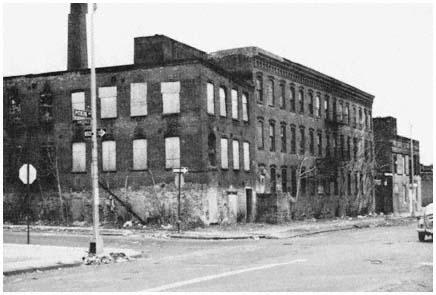

Abandoned industrial buildings in Brooklyn, typical

of thousands of obsolete facilities which

no longer provide employment for unskilled newcomers

to the region's core.

Credit: Michael N. Danielson

other low-priced gadgets—would have remained this long."[19] Indicative of the core's serious plight is the fact that the ghettos of the low-skilled are one of the older cities' remaining attractions for industry. It is questionable whether these low-wage, marginal industries can contribute much to the economic and social revitalization of the inner city. In many of these jobs, blacks and Puerto Ricans fail either to advance or to acquire transferable skills. Their earnings are low, while their prospects for technological unemployment are high.

The Burdens of the Cities

The flight of the white middle class, the influx of blacks and Hispanics, and the erosion of the economic base (outside the still-thriving CBD) have concentrated social and economic dislocations in the older cities of the New York region. As in every other major metropolitan area in the United States, the inner areas have the lion's share of the region's unemployment, poverty, slums, crime, and other social welfare problems. The adverse consequences of urban growth and change constantly threaten to overwhelm the public services of the older cities.

All these developments trouble the majority of the residents of the core, who are not poor, do not live in slums, are not on the welfare rolls, and do not commit crimes. Large numbers who live there prefer to remain in the core. Residents of Manhattan's luxury apartments and the core's other oases have combined gracious living with convenient access to jobs, entertainment and

[19] Schlivek, Man in the Metropolis, p. 164.

cultural activities. The vast horde of office, factory, and other moderate-income workers in Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx, and Hudson County have housing they can afford, and relatively inexpensive rapid transit connections to their jobs in or near the CBD. And for many others, the older neighborhoods of the core offer family and ethnic ties that are not easily severed. Nonetheless, for more and more of these people, the costs of living in the core have outrun the benefits. Fear and dislike of newcomers, congestion, pollution, noise, mediocre schools, and inadequate housing turn the thoughts of the most dedicated city dweller to suburbia. Even in a quiet middle-class backwater of the core like Brooklyn's Sheepshead Bay, "Long Island [is] the thing." As Myra Gershowitz, an accountant's wife, wistfully notes: "Everyone's moving to the island. You think you're missing something if you don't move out there."[20]