Moses and Aaron

In her study of "visual constructions of Jewishness," Gertrud Koch begins with a consideration of Adorno, Schoenberg's opera Moses and Aaron , and the Straub/Huillet film of that work.[10] Her discussion of the contradictions between mimesis and the "proscription of images" in Adorno's aesthetics relates closely to the aspects in Straub/Huillet's work I consider here in regard to Adorno and Brecht. The principal subject of Koch's book, however, is the difficulty the cinema has in creating adequate visual representations of Jews as Jews, particularly since such representations either tend to reproduce anti-Semitic stereotypes or are defeated by the unrepresentability of the Shoah . In the face of this, Koch stresses that Critical Theory's theoretical attempt to link the extremes of mimesis and the proscription of images is relevant to contemporary film.[11] Although Koch concludes that Straub/Huillet's Moses and Aaron is unsuccessful in resolving the extremes, I hope to show that this film and the short film Introduction productively explore the contradictions of politics and representation, anti-Semitism and identity. They carry on the task that Adorno valued in Schoenberg's opera, as Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe described it, "the offering of a work which explicitly thematizes the question of its own possibility as a work—this makes it modern—and which thereby carries in itself, as its most intimate subject, the question of the essence of art."[12]

Straub/Huillet's interest in Schoenberg as a basis for film is nearly as old as their Bach project. Plans to film Moses and Aaron stem from 1959, when they saw the first fully staged production at the Deutsche Oper in Berlin.[13] Their Schoenberg collaboration with the conductor Michael Gielen continues with plans for a film of Von Heute auf Morgen in 1996.

The action of Moses and Aaron is Schoenberg's retelling of the story of Moses' presentation of the Ten Commandments to the people of Israel and their worship of the Golden Calf (Exod. 3, 4, 30–32). The work breaks off at the resulting impasse between the invisible law of monotheism, for which Moses stands, and the more accessible religion Aaron represents, which includes miracles, sacrifices, and the worship of the Golden Calf. The unfinished third act occupied Schoenberg until his death in 1951, when he expressed the wish, carried out by Straub/Huillet in the film, that the final act "be staged merely

spoken, in case I cannot complete the composition."[14] Schoenberg envisioned the opera more as a staged oratorio, and Straub/Huillet's exploration of this form in film extends from Chronicle to the Hölderlin films.

Since the temporal structure of Moses and Aaron is largely predetermined by the score of Schoenberg's opera, my main focus here is its relation to cinematic space. The themes of the opera's narrative are located by Straub/Huillet in separate planes of cinematic space, allowing the spectator to move with the camera within and between these planes. By contrast, the strongly two-dimensional nature of the short film Introduction draws our attention to its use of cinematic time and its relation to Schoenberg's innovations in composition. In conclusion, I will argue that this film asserts both artistic and political freedom through its thorough separation of art from politics.

Before examining the spatial drama of the opera film, I want to note briefly a few aspects of the relation between Schoenberg's score and the score and screenplay finally used in the film. As the musical conductor for the film, Michael Gielen, has pointed out, since Schoenberg only completed a draft of the score, the work involved in producing this complete production for the film provided the opportunity to "research and present a fundamentally authentic text, definitive for our time. Here, too, in this sense it was a premiere."[15] Gielen's published comments document the quality and the thoroughness of Straub/Huillet's preparation of the opera.[16] The resulting film has since been called "the standard-setting opera film, which leaves all the others behind" and "the most radical film-opera the cinema has given us."[17] The Philips studio recording made conjointly with preparation for the film is also considered definitive (record no. 6700 084) and was awarded the Prix Mondiale du Disque de Montreaux. Gielen's record diverges from the film in leaving off the recitation of the text of the third act, a decidedly different interpretation of the unity of the work, Koch has pointed out.[18]

The nature of the recording also differs from film to record: For the film a very "dead" recording was used, with as little resonance as possible, whereas the record has the "artificial resonance" typical of the recording industry. Gielen in some ways prefers the lack of resonance, because it emphasizes the structural relationships in the music, rather than tone.[19] This structural relationship carries over into the technical basis for the filming of the performances themselves. True to their principles, Straub/Huillet rely almost exclusively on live sound in this work, with the singers recorded on camera in the theater of Alba Fucense in the Abruzzi region of Italy. The orchestral accompaniment, however, comes from a studio recording, audible to the singers as they perform through earphones hidden by wigs and costumes. The technical separation, which takes on cinematic meaning in shots I will examine later, corresponds to Adorno's observation of the musical difference between the voices and orchestra: "The unity of Moses and Aaron is created by its strictly sustained dualism. [ . . . ] The function of the orchestra as a whole is that of an

accompaniment."[20] In an acoustic as well as a visual sense, then, the film offers a dimension that other recordings of the work do not.

The other aspect, which will be largely excluded here, is the exactness with which the editing of the film follows the "movement" of the score as Gielen attests. This essay, like any analysis or viewing of the film, is thus partial inasmuch as its ignores this careful correlation of music and editing. Merely the phrase "musically necessary locations for cuts"[21] establishes the uniqueness of the Straub/Huillet approach. The relatively small number of shots in the film, seventy-seven shots over 110 minutes, arises from the difficulty of breaking between measures of twelve-tone composition. As Koch has observed, each series of notes could be related as well to the series coming after as that coming before; the cinematic consequence of this lack of hierarchy is much more camera movement than usual in a Straub/Huillet film.[22]

The emphasis of this chapter will thus be on the "cinematic space" of Moses and Aaron and its relation to the material of the opera/film, the constitution of a nation in and through history. The film takes as its starting point the assertion that "things could have been otherwise," even in regard to monotheism and the existence and nature of God. Straub/Huillet have in more recent films further investigated this interplay between myth and history, which Lacoue-Labarthe has called "the caesura of religion." Such a materialist project is not contradictory to that of humanist theology, since Martin Buber also has written, "We will not be able to reach the core of history . . ., the experience of events as miracles is itself history on a grand scale. It must be understood on the basis of history and placed within the historical context."[23]

The historical miracle at the center of Moses and Aaron is the development of monotheism among the Hebrew tribes, along with their emerging consciousness of nationhood. They created their God who chose them as His people. Even Catholic theologians describe this as a historical process, subject to change, which thus attests to the freedom of God.

The God Moses is allowed to confront is not tied to a place. He proclaims himself "God of Abraham, God of Israel, God of Jacob," and thus the God of wandering nomads, with whom He has moved and whom He has led. He prophesies and promises that He will lead the people into the land of Canaan. An unrepresentable God is a free God—God in His unfathomable freedom, from which history emerges: history which will give meaning and a goal to the life of the peoples.[24]

The existence of such a God, however, is tied by covenant to that of His People: "It is the prophecy that God's Being will be revealed in His Being-with-and-for Israel."[25]

A materialist concept of history values the historical mobility the development of monotheism represents. For this reason, Danièle Huillet accompanied the published screenplay of Moses and Aaron with a "Little Historical

Excursus," based on a variety of historical sources.[26] The essay describes just how much the Israelite nomads had in common with the other tribes of the area and thus to what extent the historical development of their religion fit their needs for progress as a nation. The significant historical dimensions parallel those in Adorno's aesthetics, that is, memory of a past, motion toward a future, and thus constitution of a group identity, historical subjectivity. In her excursus, Huillet stresses the importance of the link between the "unrepresentable God" and the freedom and identity of the Israelites: "He [Moses] was convinced—and convinced his people—that a god fought on their side who was more powerful than all the gods of Egypt: Jahweh, the Elohim of the Sinai, who would not only free the oppressed Hebrew tribes, but also would make a People out of them."[27]

The radical concept here is the importance of historical change bound up with the central existence of God: a people comes to its God; its religious life is not unchanging but moves forward, has a history. The "unrepresentable" nature of God is the driving force, the thought, that pushes onward into the future.

Thus Moses' task was a practical one: the creation of a People by means of a national religion: Jahweh is to be the God of Israel and Israel the People of God. This often-repeated formulation is Moses' guiding thought. A last trait of this national religion is its historical character.

Most other Semitic peoples had worshiped their gods since time immemorial and felt bound to them through a natural, physically related image. But on a certain day, Israel was brought to Jahweh by Moses, a personality long to be remembered.[28]

At another time Straub asserts that although Schoenberg was "anti-Marxist," his "prudent" way of working makes the opera a suitable "object of Marxist reflection":

When he talks about the "chosen people" there is a mystical idea there, which is not a Marxist idea, but which he neither takes as an end in itself. The idea of the chosen people is instrumental. It enables a step into history, as it were, as a means to something else. Subsequently, of course, the idea became an oppression. It became institutionalized. We have to start again every day, and when something becomes institutionalized it loses its revolutionary potential.[29]

The opera Moses and Aaron is centered on just this contradiction: the strength of the monotheistic idea rests on its link to a historical event, the liberation of the people of Israel from Egypt. This idea is new; it cuts a people off from its past in order to allow it to "step into history." But just this newness requires Moses' insistence that the old gods, with physical and geographic nearness to the people, be left behind. The new God cannot be seen in images.

This historical quality of God is inherently ambivalent, and here arises the conflict between Moses and Aaron. First, the newness of this God is based on "the complete, absolute separation of God, who is everything, from humanity, who is nothing."[30] This is the source of the power that could lead an oppressed people into the unknown; the power of God does not derive from any human characteristics but is something that can never quite be absorbed into human experience; "it is truly the 'completely Other.'"[31] But the fact that this power "chose" to free the Israelites and chose to speak to Moses contradicts its nature as "completely Other." Having created this nation, it is also somehow "represented" in it.

The contradiction between God as "unrepresentable" and separate from the world and God's existence for the chosen people is expressed clearly enough in the opera. Moses argues for the "unrepresentable Idea" while Aaron allows its physical representation in images. Moses expresses himself in Sprechstimme , Aaron in "melodic" tenor. The film Moses and Aaron is unique in two ways, however: first, the cinematic "representation" of the ambivalence of an unrepresentable God actively influencing reality; and second, the transformation of this historical conflict into an aesthetic experience for an audience. As Adorno's aesthetic theory suggests, the dilemma of art is similar to this contradiction. It points toward freedom, but it is by nature separate from the society in need of this freedom. It represents the unrepresentable.

Straub/Huillet's film balances this ambivalence by separating the kinds of narrative space created at each point of the dilemma. In the first place, all narrative action that involves either performance of the opera or the temptation of the people to return to religious images is tied very strictly to the physical space of and motion within the amphitheater of Alba Fucense. On one level, the entire opera is confined to this space; all the "images" created by Aaron and the people of Israel as represented in the opera are photographed there. The "unrepresentable," the mythical step into history that Moses "represents" as well as the implied aesthetic step into history for the spectator of all this, is provided only by the material means of the cinema that go beyond the opera's performance.

The early shots establish this contrast. As Moses receives his call to lead the people out of bondage, we see him and the space in which he will continue to be photographed in an extended shot tracing the extremes of the camera's mobility, shot 10. The shot moves from an extreme close-up of Moses by way of a 300-degree pan around the amphitheater that is to become the setting for the action, and during this pan it tilts from a high angle showing the ground from over Moses' left shoulder to a low angle showing the mountains in the distance outside the amphitheater.[32]

Shot 10 thus sets Moses within his sphere of action. As he receives his call from God, we see the amphitheater in which the "drama" of leading the people

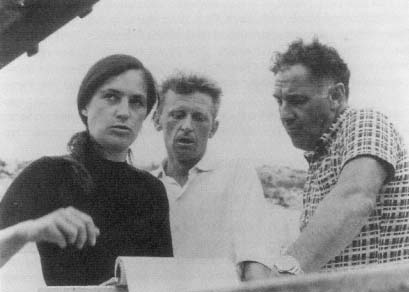

Straub/Huillet directing Schoenberg's Moses and Aaron with

cinematographer Ugo Piccone, right.

Courtesy Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek.

will be enacted and, at the end of the pan, the mountain where the "idea" has originated. As yet the people are not visible, since the spiraling tilt has literally gone over the heads of the other singers. They do not exist until Moses (or God) addresses them through Aaron. Because this initial view of Moses is an oblique one from over his shoulder, the viewer does not take the place of speaker or listener at this stage but instead observes the camera's passage from Moses' position to the "goal" this idea represents. As Straub has said of this shot, "All the themes of the film are there." The pan halts on its long shot of the distant mountains with the words of the burning bush, "And this I promise to you: / I shall conduct you forward, / to where, with the Eternal Oneness, you'll be a model to every nation."[33] As in the rest of the film, the Verheißung , the otherness of God, the unrepresentable, is pointed to by way of cinematic techniques that are also "other" to the drama within the amphitheater.

Walsh links the historical and aesthetic/philosophical issues of the film in the following manner: "Co-extensive with Moses and Aaron's conflict over how to lead the people is the problem of how to 'represent the unrepresentable': how to realize the idea in an image without betraying the idea. In short, they are concerned with the ideology of representation, and the film may be read entirely on this level."[34] The "ideology of representation" is therefore a theme for both the people of Israel and the spectators of the film, but by different means.

The chorus in Moses and Aaron .

Courtesy Museum of Modern Art.

The film's manner of separating these two "audiences" determines its structure to a great degree.

After the spatial tour de force of shot 10, the film sets up the "rules of the game," as Huillet calls them, for the drama within the amphitheater. These are the spatial relationships between Moses, Aaron, the chorus, the priest, the man, the young man, and the young girl. These relationships, like the motion of Moses from the theater to the mountain, are constructed through an external cinematic device. During these exchanges in Act I, leading to the liberation of the Israelites from bondage, the camera remains in the center of the ellipse. Thus every shot of one of the "roles" listed above has the amphitheater as its background. The choir is arranged in a square of six rows instead of the customary four, so that it, like the other actors, can always have space around it and usually the wall of the amphitheater in the background. The existence of the people is thus always accompanied by evidence of human history.

The effect of this arrangement is established in shots 19 and 22, which without editing include the positions of all the actors in the amphitheater. Since all the positions are photographed here in a single pan, the spectator and the camera do not identify with any single position. There is never a shot, for instance, that shows Moses from the point of view of the chorus whom he addresses. But the camera is still within this configuration. It never again stands behind Moses to reveal at once his position and the location of the listeners,

Moses and Aaron : The amphitheater at Alba Fucense

showing arrangement of characters for Act I. Graphic: Andrew Reich.

which would make the spectator superior to this relation. Thus the spectator is not confined to a point of view but still senses the confinement of the theater space. This constant background serves to emphasize at the same time the static performance quality of the work, the separateness of this historical action from the present tense of the spectator and the camera movement, and the equality and interdependence of each of the musical and dramatic parts.

Walsh has noted the narrative structure in the way camera placement varies the positions of Moses and Aaron in the image: "insofar as shots 4 and 6 bracket shot 5, Aaron metaphorically surrounds Moses—is his voice."[35] What Walsh notes here is that changing camera placement shows Aaron in various positions with respect to Moses, while Moses remains static, photographed from the front. Walsh also notes the function of camera movement to provide the changing positions of Moses and Aaron in shot 24. Schoenberg has specified such shifts in distance between Moses and Aaron and between each of them and the audience.

Straub/Huillet's mise-en-scène respects the sense of an oscillating power struggle that is here Schoenberg's concern, but instead of having Moses and Aaron move (they remain static throughout the shot), the camera moves, the relative sizes of Moses and Aaron shifting in the frame as the camera tracks around them, and back again. The shot thus functions narratively, but Straub/Huillet simultaneously accomplish more than this, since their materialist use of the medium becomes apparent once again, this time through the contrast between the rapidly shifting background of the amphitheater and the slowly changing relations between Moses and Aaron: this dramatic separation of foreground and background has a strong two-dimensionalizing effect.[36]

As in twelve-tone musical technique, then, the importance of the camera in this narrative thus equalizes its elements, flattens them out in visual space, and emphasizes their abstract interrelatedness, existing wholly in the past.

So far, we have seen that neither Moses' confrontation with God nor his (and Aaron's) persuading and leading the people is acted out. Instead, these events are represented through relationships of cinematic space and camera movement. A sharp contrast to this technique of "representation" is thus provided by those aspects of the opera that are acted out. These elements belong entirely to Aaron's transgression of the prohibition of images and are also largely confined in space to the amphitheater. We do not see Moses go to the mountain or return; we do not see his receiving the Ten Commandments. But in his absence, we do see the unification of the twelve tribes, whose princes arrive at the amphitheater on horseback. The adoration of the Golden Calf is acted out, as are the representations of decadence, the orgy, the animal and human sacrifices. These activities are thus aesthetically and thematically opposite to the stylized manner in which Moses received and conveyed his mission, "the unrepresentable." However, this is not to assert unequivocally that Aaron's transgression is condemned by the film. The expressions of worship involved with the Golden Calf do indeed arise from the real-life experience of the people of God. They also have history and are a way of joining history. Thus one must note that the Golden Calf is meant to represent the liberation from bondage and that it is made of the gold the people themselves had gathered (Aaron: "Ihr spendet diesen Stoff, / ich geb ihm solche Form";

Aaron (Louis Devos). Courtesy Museum of Modern Art.

shot 30). Even the destruction and the self-destructiveness acted out are desensationalized. They are not made more powerful by way of cinematic effects but are merely presented as "representations" of these transgressions. Gielen finds the "renunciation of the orgy" of great importance to the film, stressing, among other things, the "unprofessional" dance of the butchers, performed by professional dancers.[37] Koch also accurately observes that this method of presenting the ballet is part of the price Straub/Huillet have paid for treating the opera as a text, including this portion which approaches conventional film and theater spectacle. But she seems to underestimate the significance of her own crucial observation: "The naturalistic details and objects, recommended by the composer and potentially offering considerable visual spectacle, have the effect in the film as theatrical props in the literal sense."[38] A powerful shock is produced by the juxtaposition of music, theatrical spectacle, the athletic skill of the Cologne ballet dancers, direct sound, and "the frustrating precision of the framing." The final image of the ballet is of the gravel base of the amphitheater, a frame the dancers have left, filled only by the sound of their panting from such exertion.[39]

One could also argue that this distancing from the "pleasure of the spectacle" is necessary to historicize it. The dance of the butchers is not only the music most closely resembling traditional program music in Schoenberg's opera,[40] it is also the only portion ever performed during his lifetime. As such, it has already been "realized" in the past to a greater degree than the unfinished opera as a whole.

Concerning the separation of life and art and the question of representing the unrepresentable, the "artlessness" of these scenes becomes extremely complex. It seems particularly fitting that virtually all critics have been disturbed by the orgy scenes and the dance of the butchers as Straub/Huillet have filmed them, since they portray the transgressions of the people, who attempt to represent their religion in the forms of everyday life. Since both true art and true holiness are separate from everyday life, these scenes are neither artful nor reverent. Despite their lack of art, however, they do provide a contrast to the rest of the film by capturing some of the spirit of real human life in its physical richness and diversity and give some credence to the "demands of the peopel" as even Eisler and Adorno urged. The images of the night of the orgy are cool and comfortable compared to the stark bright heat of most of the film's settings. The image of the moon in shot 69, for all its associations with death in the shots preceding it, is an inviting one. And the life breathed into the amphitheater by the arrival of the animals for sacrifice is also attractive as a sign of everyday living; their surplus of sound temporarily overwhelms the music. Furthermore, the unconvincing depiction of the suicides in the orgy also has an affirmative, realistic note: self-destruction is not natural after all, and thus it is difficult to depict without the aid of professionals in the art.

The transgression against the unrepresentable God thus is represented without "art." It is merely acted out, quite literally following the libretto, set within the reality of human life. The cinematic art of this film thus is linked to the opposite element: the unrepresentable God, the idea of freedom, the negation of reality, otherness. The ultimate expression of this freedom occurs in the film when the cinematic apparatus leaves the realm of narrative representations to suggest something beyond them. Preparation for this liberation from the historical narrative is provided by the central placement of the camera in the amphitheater. All the narrative action is focused inward, but the camera's perception of it can escape. Suggestions of this possible escape reside also in the fact that Moses' journey is not seen, nor is his destruction of the stone tablets narratively completed. Most important, the destruction of the Golden Calf is not acted out but is achieved by the fade to white offered only by cinematic technique. Here the question of the audience rises again. Moses is able to destroy the image, but even this destruction is an image: "Auch die Zerstörung des Bildwerks war nur ein Zeichen, ein Bild."[41] But in the context of the film, the destruction of the Golden Calf and, more important, the liberation of the people from bondage are radically different kinds of images from those positive ones worshiped within the narrative drama. The destruction of the Golden Calf, for instance, is not acted out dramatically but occurs through the fade of the film image. This is not to say that the white film or black film is any less a "sign" than the calf, but it does have a different audience: the calf is an image for both the people of Israel and for the viewer of the film; the fade to a white screen is only an image for the viewer. Even more liberating is the travel of the camera

outside the narrative space of the amphitheater. In this motion it follows none of the actors of the film, not even Moses. The two long panning shots of the Nile, shots 42 and 43, thus do much more than represent the escape of the Israelites from Egypt described in the accompanying text. To a great extent, it replaces this escape with an opportunity for the spectator to be both within and beyond the conflict of the film. At this point, we are on a different level from an audience reflecting on an "estranged" opera performance. The cinematic structure both confines and abandons the operatic performance. The audience for this pan across the Nile valley is also not the people of Israel, because they are enclosed in the space of the amphitheater and are not given the freedom of movement that the camera has. The chorus heard on the sound track is suddenly not present to the shot. The opportunity of freedom offered by this cinematic transformation is to become an audience for (and in) which the unrepresentable is brought into existence. As Jahweh is to the people of Israel, so is the authentic work of art to the audience that might exist for this film.

The final confrontations between Moses and Aaron also complete the separation of the formal structure of the film from the historical dilemma of their two ways of leading the people. As shot 10 united Moses' journey with the promise of the burning bush to free the people and to lead it, here the process is reversed. In shot 78, Moses destroys the stone tablets, the result of the foregoing struggle. Aaron and the people are no longer seen, and this is another parallel to the beginning. But Aaron's voice argues that the signs that lead toward the promised land, the pillar of fire by night and the pillar of clouds by day, are no less signs from God than the burning bush. A moving camera points to the distant sky outside the amphitheater as Aaron sings "Darin zeigt der Ewige nicht sich, / aber den Weg zu sich und den Weg ins gelobte Land" (shot 79). The same camera perspective that had inspired Moses to lead the people into the desert (into freedom) inspires Aaron to lead them out again. Act II ends as the opera began, with Moses alone, with only the arid ground around him.

The photography of Act III takes another step out of the context of the amphitheater. Like the long pans of the Nile, this shot is lush, fertile, and cool, with a mountain and a lake in the background. Lacoue-Labarthe has observed that by staging the first two acts in a Greek theater, Straub/Huillet have emphasized that this portion of the opera is the "tragedy" of Moses.[42] The modern dilemma enters with the opera's unfinished state, both a historical and a conceptual contradiction that cannot be resolved. This is the "caesura" that Lacoue-Labarthe locates in Straub/Huillet's approach to the third act.

The dramaturgical choice of Straub and Huillet is particularly illuminating: for not only do they play this rarely spoken scene in the unbearable silence which succeeds the unfurling of the music, a silence that Adorno analyzes so well, but they have it played in a place other than that which, since the outset, was properly the stage or the theater. They do this in such a way that it is not only the tragic

apparatus as Adorno understands it that collapses in a single stroke, but the entire apparatus which kept Moses within the frame of opera or music-drama. And it is here, probably, that religion is interrupted.[43]

Again, Straub/Huillet allow the cinema to take over: Moses and Aaron are no longer in the desert; they have been transported to a new setting, not by their own action, but by the camera's. Here, too, they do not act; all motion is supplied by the camera. The camera takes in first both Moses and Aaron, who is bound and lying in the mud, insisting that his images served the survival of the nation: "for their freedom—so that they would become a nation." Then, without a cut, the camera pans to Moses, who has the last word. The lack of editing unifies the scene rather than breaking it up into its contrasting parts.

Originally, the escape into the desert had been an escape from bondage and the creation of a nation. Now Moses proclaims that the nation will always need to return to the desert, as punishment for the successes of its own creation.

Whensoever you went forth amongst the people and employed these gifts—

which you were chosen to possess

so that you could fight for the divine idea—

whensoever you employed those gifts for false and negative ends,

that you might rival and share the lowly pleasures of strange peoples,

and whensoever you abandoned the wasteland's renunciation

and your gifts had led you to the highest summit,

then as a result of that misuse you were ever hurled back

into the wasteland.[44]

The separation of God from the people is the reality that makes it possible for this people to depart from and return to its covenant; the absoluteness of God's otherness makes possible a historical continuity for the "chosen people." The otherness of God is the basis of their freedom. But to "become a people," the images of Aaron were also necessary, and Straub/Huillet thus maintain the dissonance of this contradiction to the end. Aaron, who had been the man of melody and images, speaks his last words from offscreen; and the stage direction indicating that he falls down dead thus is negated. The only image at the film's end is Moses proclaiming the unity of the people and God without images.

The otherness of the cinematic structure in this film is the basis for the spectators' freedom. Since the audience is not in the cinematic space that confines the historical characters, it can see beyond them, can imagine the possibility of another liberation that cannot be represented because the people who could claim it do not exist. The film proposes an escape from its own images but does not depict either a leader or a nation that could carry out this escape. It returns to the limits of its own forms; since it is not the world, it

cannot depict freedom in the world. Even the magnificent freedom of the panoramas of the Nile, freedom offered to an audience able to accept it, begins and ends in bondage, in the history of its own mechanical creation, its unreality. Visually, shot 43 encompasses the hopes and the limits of the entire film as well: it begins with the arid rocks at the left of the frame, moves to take in the glorious green expanse of the Nile valley, then returns to the same arid rocks at the right of the frame, just as the chorus repeats the word "free." This film thus does not unselfconsciously indulge the audience's desire to gaze at natural beauty and evades, I think, the trap Gertrude Koch has consigned it to: "Thus both shots of pure nature get caught up in the wake of the ambiguity of Moses and Aaron , including its Zionist, political-biographical aspect."[45] The film can escape the desert and point toward the promised land, but it cannot enter it; liberation in reality and liberation in the cinema are separate propositions. The proscription of images and cinematic pleasure are both upheld.