Role Portraits and Self-portraits in Costume

Corinth's figure compositions of these years are closely related to both his portraits of actors in their roles and his interesting self-portraits and double portraits in which he wore disguises he associated with prototypical human experiences. The role portraits were a direct result of Corinth's work for the theater of Max Reinhardt, with whom he collaborated from 1902 to 1907, contributing designs for costumes, and in some instances sets, for a total of eight productions. Reinhardt had left Otto Brahm's ensemble at the Deutsches Theater in 1902 to become director of the Kleines Theater. The event not only marked a turning point in Reinhardt's career but also ushered in one of the most exciting periods in the history of the Berlin theater. When in 1903 the

Kleines Theater proved too small to hold the audiences that Reinhardt's productions attracted, the enterprising young director rented the Neues Theater as well. In 1905 he assumed responsibility for the Deutsches Theater and the following year extended his reign to the Berliner Kammerspiele.

For years Otto Brahm had fought for the recognition of naturalism on the German stage; Reinhardt now sought to reveal the content of any drama through expressive features in both acting and decor.[44] Assigning a significant role to the stage designer, he eventually achieved a synthesis of content and appearance by using sets and costumes not merely to create the illusion of nature and historical plausibility but to reveal the very essence of the play.

This new emphasis on creating an evocative milieu seems to have found its first full expression in Reinhardt's staging of Maeterlinck's Pelléas und Mélisande , which opened on April 3, 1903, at the Neues Theater. Corinth designed the costumes for the play and together with Leo Impekoven also worked on the sets. Unfortunately, only a fragmentary image of Corinth's work for the theater can be reconstructed from scattered reviews and a few surviving photographs. That Corinth and Impekoven successfully transformed the naturalistic stage into an instrument of greater expressive force is suggested by Carl Niessen's observation on the scenery for Pelléas und Mélisande : "Just as in Maeterlinck's poetic world reality lies behind things and can only be imagined with apprehension and longing, so a mysteriously threatening darkness emanates from the slender gray trees of a forest."[45] And Max Osborne speaks of the same setting as "a fairyland with wide open eyes, a world of mystery and fathomless depth, illumined for a brief moment by a ray of light."[46]

The most controversial play on which Corinth collaborated with Reinhardt was Oscar Wilde's Salome , first performed in Germany before a private audience at the Kleines Theater on November 5, 1902. The play premiered before a general audience almost a year later, on September 29, 1903, at the Neues Theater. Corinth designed the costumes; the sculptor Max Kruse was in charge of the sets. Kruse replaced the customary painted backdrop with a new type of three-dimensional stage architecture that was to become a hallmark of Reinhardt's productions. Beyond Herod's palace, flanked by guardian monsters and lions, was a gloomy night landscape. The shadows cast by the statuary and the building blocks of the scenery created a sense of foreboding as soon as the curtain rose. Corinth's costumes added barbaric splendor to this ominous mood. In their garish magnificence, the multicolored robes, encrusted with colored stones, expressed the high-pitched depravity that propelled the lurid plot.

In addition to his work on Salome and Pelléas und Mélisande , Corinth designed costumes for Hofmannsthal's Elektra (1903) and Gorki's Nachtasyl (1903), the sets for Wedekind's König Nicolo (1903), and perhaps both the sets and costumes for Shakespeare's Merry Wives of Windsor (1903). He also designed figurines for the 1907 productions of Hamlet and Lessing's Minna von Barnhelm .[47]

Corinth's work for the Berlin theater may well have helped to intensify the dramatic character of his contemporary figure compositions, for despite the demands he made on his models, it is unlikely that these paintings were entirely staged in the studio. They resulted from a synthesis of content and appearance, a pictorial challenge to which Corinth alluded in his teaching manual when he explained the special difficulty of depicting an actor in a given role, a task that requires coming to terms not only with the reality of the sitter but also with the illusion of the disguise.[48]

In Gertrud Eysoldt (1870–1955), whom he painted in January 1903 in the title role of Oscar Wilde's Salome (Fig. 102), Corinth encountered an unusually versatile actress whose ability to bring to life the heroine's hybrid character allowed him to experience the biblical figure directly. Eysoldt imbued Herodias's daughter with both childlike innocence and lustful cruelty. According to Tilla Durieux, another great exponent of the role, Eysoldt's body resembled that of a child and she knew how to accentuate the ambivalence of her child-woman persona without attracting the attention of the censors.[49] Unlike the anecdotal figure composition he had devoted to the subject in 1900 (see Plate 12), Corinth's role portrait sought to capture the ambiguity of the character's emotions as invoked by Eysoldt. Soon after the play's first private performance at the Kleines Theater, she posed in Corinth's studio, wearing the costume and the jewelry he had designed for her and holding the dish with the Baptist's severed head, a grisly prop borrowed for the occasion from Reinhardt's theater. Unaided by the ambience of the stage action, Eysoldt has assumed the character of the vile princess in the play's closing scene. Her wish fulfilled, Salome has taken possession of her prize and anticipates the ecstasy of kissing the dead prophet's lips. Without any further reference to Wilde's play, Corinth in this portrait represented a generalized image of depravity, partly, perhaps, in response to the then current vogue for pictures of the prototypical femme fatale but surely also out of his own interest in the universal human dimension.

The special nature of the Eysoldt-Salome portrait is evident if the painting is compared either with Max Slevogt's portrait of the Philippine dancer Marietta de Rigardo (1904; Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Neue

Figure 102

Lovis Corinth, Gertrud Eysoldt as Salome , 1903. Oil on

canvas, 108 × 84 cm, B.-C. 252.

Present whereabouts unknown.

Photo: after Bruckmann.

Meister) or with Slevogt's portrait of the singer Francesco d'Andrade in the role of Mozart's Don Giovanni, the so-called White d'Andrade (1902; Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart), which was exhibited with great success at the Berlin Secession in 1902. Slevogt re-created in both paintings the excitement of an actual performance and thus—in contrast to Corinth—invited the viewer to experience these pictures in a specifically theatrical context.

Corinth's portrait of Rudolf Rittner (1869–1943) in the role of Florian Geyer (see Plate 16), painted in 1906, is no doubt indebted to Slevogt's example insofar as it emphasizes physical action rather than psychological expression. The painting shows the actor in the climactic scene from the last act of Gerhart Hauptmann's drama about the Peasants' Rebellion. Having sought refuge at Castle Rimpar, Florian Geyer has been routed out by his enemies. Exhausted and outnumbered, he summons all his strength and counters the demand to surrender with a thundering challenge. A few moments later he is killed by a shot from the crossbow of Schäferhans.

Figure 103

Lovis Corinth, Tilla Durieux as a Spanish Dancer ,

1908. Oil on canvas, 85 × 60 cm, B.-C. 350.

Sophie Althaus, Riezlern.

Rittner, whom Max Reinhardt called a man of "healthy, strong, impulsive temperament,"[50] was the ideal interpreter of Hauptmann's hero and secured for Florian Geyer a permanent place in the German repertoire when Otto Brahm revived the play at the Berlin Lessingtheater in 1904. In Corinth's painting too the actor and the character have become one. Yet in Rittner's vigorous portrayal Corinth himself found embodied not only the essence of Hauptmann's drama but also a struggle transcending that of the historical person. The large size of the painting monumentalizes one person's battle against an unknown fate. Although Corinth depicted an anecdotal moment in the action, he isolated the actor—as in the Salome portrait of Gertrud Eysoldt—from the larger narrative context of the play, replacing the hall at Rimpar with a neutral ground. And Florian Geyer's enemies are anonymous foes whose threat is all the more awesome because they cannot be seen.

The portrait that Corinth painted in 1908 of Tilla Durieux (Ottilie Godeffroy, 1888–1971; Fig. 103) was not inspired by a theatrical performance. The

actress's posture is motivated by nothing more than the desire to create a mood appropriate to the long-fringed scarf she wears over her left shoulder—a gift from Paul Cassirer, who had brought it earlier in the year from Spain. Nonetheless this painting is connected to the role portraits of Eysoldt and Rittner. The only difference is that Durieux does not play a specific part but expresses her joy in a prototypical context. For the moment she simply is "la belle Espagnole dansante la sequedilla," as the inscription—written, though not entirely idiomatically, in French, perhaps in allusion to Bizet's opera—in the upper left corner of the canvas indicates. The ease with which Durieux brought to life virtually any character has become legendary. She played leading roles in the dramas of Shakespeare and Schiller and was equally at home in the naturalist and symbolist plays of Hauptmann, Shaw, Wedekind, and many others. Her range and power of characterization made her the quintessential "Reinhardt actor," for Reinhardt thought of the theater as the collective manifestation of human experience, and he demanded that an actor use a role to fathom his own inner being: "The actor must not disguise but reveal. . . . With the light of the poet he descends to still unpenetrated depths of the human soul, and from there he emerges—hands, eyes, and mouth full of miracles."[51] Tilla Durieux echoed Reinhardt's insistence on self-revelation when she called the actor "an exhibitionist devoted to truth," who tears off every mask before the public until the throbbing flesh lies exposed.[52]

This intuitive approach to acting parallels Corinth's approach to his role portraits, his tendency to enlarge their meaning beyond the historical-ideal truth of the characters depicted, and also sheds light on a group of self-portraits in which he wore various costumes to engage in a self-revelation not possible in the conventional self-portrait. Seven of the eleven self-portraits he painted during his first ten years in Berlin show Corinth in some sort of disguise. In the earliest of these, from 1905, he depicted himself as an ecstatic bacchant with a wreath of vine leaves on his head (see Plate 17). In keeping with Durieux's demand that actors expose themselves in their roles, Corinth here cut through surface appearances by attacking the canvas with ferocious strokes of the palette knife, transferring his heightened emotional state to the texture of the paint itself. According to Charlotte Berend, this disguise came quite naturally to the painter. "When Corinth wound vine leaves in his hair, when he lifted his glass and embraced his bacchic young wife, the world around him changed into the realm of Dionysus, to whom he felt closely allied."[53] In 1908 Corinth elaborated the bacchic allusions of the double portrait of 1902 (see Fig. 83) into a more specific costume piece (B.-C. 355) that does indeed vividly illustrate Charlotte Berend's recollection, except that the bacchante at the painter's side is not his wife but another model who hap-

pened to be conveniently at hand. Corinth's sensuous nature was apparently evident to perceptive eyes in a more public context as well, as the following irreverent description of the painter by Meier-Graefe indicates:

Like a polar bear with small red eyes he moved through the ballrooms of Berlin. He looked greedily at many a banker and at many a banker's wife as she danced in his arms: a pig ripe for slaughter! It was one of the joys of the Berlin winter to watch him dance. At dinner he always had two jugs of wine next to his plate. People spoke to him about Impressionism and sensibility. Corinth was, in turn, Florian Geyer, Samson, Arminius the Liberator, a tamed Hun. If one half-closed one's eyes, one saw naked limbs move underneath shaggy fur. One young lady swooned.[54]

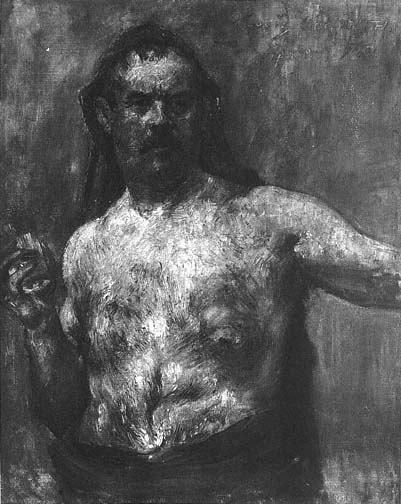

Closely related to the bacchic self-portraits are two self-portraits, from 1907 (Fig. 104) and 1909 (B.-C. 400). In both Corinth is nude except for a curious headdress of red cloth that trails down over his back and shoulders and, in the earlier work, is gathered up around the waist. In each case the painter projects an image of physical vigor on a primeval level, and both self-portraits have been seen as conjuring up memories of "lost cults, . . . drink offerings, and ancient mysteries."[55] In each work, however, Corinth's skeptical expression as he gazes at his mirror image is puzzling. He seems to be contemplating an illusion he knew he could not represent. The mood of uncertainty is further emphasized by the word ipse inscribed on the painting from 1907 and the even more eloquent inscription on the later work: Aetatis suae LI . That Corinth's health was seriously undermined at the time he painted these pictures is suggested by the recollections of his student Margarethe Moll. Writing about the circumstances surrounding the portrait he painted of her in 1907 (B.-C. 340), she mentions that the hands of the painter, then only forty-nine years old, trembled noticeably and that during one of their outings Corinth had considerable difficulty entering and leaving their boat without assistance.[56]

In the prototypical roles of these self-portraits that could give his character a generalized dimension, Corinth continued to celebrate the Nietzschean ideal of the natural and instinctual individual who—unhampered by decorum—seeks regeneration in spontaneous actions. Corinth's self-portraits in the armor of a medieval knight are reminiscent of a similar idea expressed in It Is Your Destiny (see Fig. 63), the watercolor drawing from the mid-1890s. There are two pictorial sources for these paintings. Corinth no doubt remembered the self-portraits in armor that Wilhelm Trübner had painted in 1899, and a visit in 1907 to Kassel, where he copied Frans Hals's late Portrait of a Man in a

Figure 104

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait with a Glass , 1907. Oil on canvas,

120 × 100 cm, B.-C. 344. National Gallery, Prague (0-14782).

Photo: Jaroslav Jerábek[*] .

Figure 105

Lovis Corinth, The Victor , 1910. Oil on canvas, 138 × 110 cm,

B.-C. 414. Present whereabouts unknown.

Photo: Bruckmann, Munich.

Slouch Hat (B.-C. 333), brought him face-to-face with Rembrandt's animated Self-Portrait in a Helmet , one of several early Rembrandt costume self-portraits with which Corinth was surely familiar.

In the double portrait from 1910 (Fig. 105) Corinth places his hand on the shoulder of Charlotte Berend as if taking possession of a prize after a victorious battle. Charlotte Berend, in turn, revels in the strength of the conquering hero, nestling seductively against the gleaming armor. In the self-portrait from 1911 (Fig. 106) and the related bust-length self-portrait from the same year (B.-C. 494) Corinth's expression conveys unyielding determination, the readiness to meet any challenge.

Figure 106

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait as a Standard Bearer , 1911. Oil on canvas,

146 × 130 cm, B.-C. 496. Present whereabouts unknown.

Photo: Marburg/Art Resources, New York.

Both personal aspirations and Nietzschean notions of the warlike Übermensch who sets his own moral code underlie the conception of these paintings. Corinth's almost Darwinian view of life and his belief in the survival of the fittest are suggested by a comment in his autobiography on the faculty intrigues at the Königsberg Academy that eventually led to the resignation of his teacher Otto Edmund Günther:

Since the battle for existence forces the artist to do his best, the competition is extreme. It does not matter whether his colleagues, even his best friends, perish all around him, as long as he wins out as the strongest. As long as the strength of the victor remains decisive in this battle, nobody needs to be pitied, for it is the fate of the weak to succumb to the strong.[57]

On the following page he added this advice: "Use all your might to achieve your highest goal. For all I care, use your greater strength to push your rivals against the wall until they can no longer gasp."[58]