The Second Initiative (1791–1793)

The revolutionary law of 19 July 1793, which defined the legal limits and powers of the author and laid the foundation for republican publishing, has served as the basis for French publishing to this date. It is still the first standard citation in French law school textbooks on literary property.[69] In order to understand how a law finally succeeded and why it took the form it did, critical changes in the revolutionary context between 1790 and 1793 must be considered.

In 1791 there was a crucial shift in the balance of forces for and against the notion of a "limited property right." The suppression of the Publishers' and Printers' Guild in March 1791 had dealt a severe blow to the pro-property corporate lobby. A distinct law on libel and sedition was incorporated into the Constitution in September 1791, leaving the property question to be resolved independently of the issue of censorship. This separation significantly depoliticized the property issue. The Hell proposal, which circulated for public discussion in those uncertain months of the summer of 1791, appears never to have reached the floor of the assembly for a vote. By the fall of 1791, it had become clear that the advocates of perpetual private property in ideas had wasted their energies by courting the wrong legislative committee.

The transfer of power from the Constituent to the Legislative Assembly on 1 October 1791 was accompanied by a reorganization of the structure of the assembly's committees. With this reorganization, jurisdiction over the question of literary property passed from the Committee on Agriculture and Commerce to the newly formed Committee on Public Instruction under the presidency of Condorcet.[70] He was joined on the committee by, among others, Sieyès.[71] Thus the question of literary claims, first raised in 1790 as part of a repressive police measure, and then as a commercial interest, was, by virtue of changing circumstances, recontextualized as a question of education and the encouragement of knowledge.

By 1791, moreover, the results of a second wave of agitation for authors' rights reached legislative formulation. This agitation came, not from corporate interests, but rather from authors for the theater protesting the monopoly of the Comédie française on dramatic works. Since the founding of the Comédie française in 1680, it was only theater directors, not playwrights, who could legally receive "privileges" to present and publish theatrical works.[72] This monopoly had not been affected by the reforms of 1777. The agitation of "unprivileged" playwrights was therefore crucial in disassociating the cause of "authors' rights" from a rear-guard defense of old-regime privileges and realigning it politically within the prorevolutionary attack on privileged interests.

Theater authors began their agitation in 1790 with the creation of a committee led by the playwright Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais in order to assert the rights of dramatic authors to their own works and to call for the aboli-

tion of the privileges of the Comédie française. A petition of protest bearing the signatures of twenty-one writers was presented to the National Assembly by LaHarpe on 24 August 1790. This petition was essentially an effort to reintroduce into the assembly the clauses of the Sieyès proposal that had pertained to the theater and property in dramatic works. Anyone, they argued, should be free to open a theater. The works of authors dead for more than five years should be considered "public property," but no one should be allowed to represent or publish the dramatic works of living authors without their written consent.[73] The petition was sent to the Committee on the Constitution.[74]

LaHarpe's plea did not fall upon deaf ears. In fact, supporters of the Comédie française charged that the petition drive had been instigated by a key member of the very committee to which it was submitted: "It's chez M. de Mirabeau . . . that this petition was cooked up."[75] Whether true or not, there can be little doubt that Honoré-Gabriel de Mirabeau helped to advance the cause of the petitioners.[76] Less than a month later, on 13 January 1791, the Committee on the Constitution presented a projet de loi drafted by Mirabeau on behalf of the petitioners to the National Assembly.[77]

The Mirabeau proposal, presented by Isaac-René-Guy Le Chapelier on behalf of the committee, was essentially a redrafting of the articles of the Sieyès proposal pertaining to literary property, but this time on behalf of theater authors alone. In contrast to the Sieyès proposal, however, the preamble of the new proposal laid stress, not on authors' rights, but rather upon the rights of the public. Thus Le Chapelier argued:

In soliciting for authors . . . exclusive property rights during their lifetime and five years after their death, authors acknowledge, even invoke, the rights of the public, and they do not hesitate to swear that after a period of five years the author's works are public property. . . . The public ought to have the property of great works. . . . But despotism invaded that communal property and carved it up into exclusive privileges.[78]

The authors represented themselves as servants of the public good, of its enlightenment, in opposition to the private interests of publishers and theater directors. Thus the authors themselves rejected the Diderotist argument for unlimited and absolute claims upon their texts and, reviving the compromise position of Sieyès and Condorcet, presented themselves as contributors to "public property" and guardians of the public claim to the nation's cultural commons. The author was now depicted as a hero of public enlightenment, rather than as a selfish property owner. Unlike the Sieyès proposal, that of Le Chapelier was passed into law, on 13 January 1791. The law abolished all past "privileges" and recognized the theater author's claims as exclusive property rights until five years after the author's death, at which point they would become part of the public domain.

This law, however, did not cover the work of authors in genres other than the theater. The initiative to define the legal status of all authors now passed to the

newly formed Committee on Public Instruction. Ironically, it was the recently empowered authors of dramatic works who again brought the issue to the attention of the committee. On 6 December 1791 the Committee on Public Instruction received a request from a deputation of authors headed by Beaumarchais to hear their charges against the directors of the theaters for noncompliance with the law of 13 January 1791. The theater directors had chosen to interpret this law to apply only to future works, leaving them free to present any work, even by a living author, which had already been printed or published. Further, they claimed publication rights on any work contracted by their companies prior to the law.[79]

As the result of a series of meetings, the committee drafted a projet de loi that was presented by Gilbert Romme on its behalf and passed in the Legislative Assembly on 30 August 1792.[80] The law represented a victory for the theater directors. It upheld all contracts between authors and the theaters prior to the passage of the law of 13 January 1791 and sustained the exclusive right of the theaters to stage any work performed prior to the passage of the law. Needless to say the law met with vociferous protest from authors. This time it was the playwright Marie-Joseph Chénier who headed up the protest with a letter and petition to the Committee on Public Instruction on 18 September 1792.[81] The law, Chénier argued, had been slipped through by Romme without the support of the majority of the committee members.[82] The committee reopened the question as a consequence of this protest.[83]

It was not, however, just writers of dramatic works who expressed discontent over the course of 1792. On 2 January 1792 the committee received a petition from thirty authors and editors of music, not covered by the law of 1791, in which they begged the "National Assembly, in all its wisdom, to find a means to protect their property and prevent pirating."[84] The novelist Jean-Baptiste Louvet wrote to the convention as well, requesting permission to present a petition "calling for a law against priaters, who are destroying the book trade and bringing me to ruin."[85] These appeals were not to go unnoticed. On 20 February 1793 the Committee on Public Instruction finally assigned Chénier the task of drafting a general law against priate editions in all genres.[86] News of the forthcoming Chénier proposal was announced in the Moniteur in April, but Chénier did not succeed in getting the floor of the convention during the troubled spring of 1793.[87]

After the "revolution" of 31 May to 2 June 1793, which purged the Girondin faction from the convention, Condorcet ceased appearing at committee meetings. A month later he was in hiding.[88] Sieyès took over the presidency of the committee on 23 May, but he and Chénier both soon withdrew as well.[89] Denounced as Girondins, all three were formally excluded from the committee on 6 October 1793.[90] It is ironic that the Girondin law that founded the basis of modern French publishing should emerge precisely at the moment of the Jacobin victory that suppressed its authors. Indeed, it was the Jacobin consolidation of power that made it possible to pass the law. On 19 July 1793 the convention at last heard

Chénier's proposal presented on behalf of the Committee on Public Instruction by Joseph Lakanal.[91] It was passed with no recorded discussion.[92]

The decree adopted on 19 July 1793 amounted to yet another version of the Condorect/Sieyès proposal of 1790. No longer perceived as a "Girondin" police measure intended to ensure the accountability of authors, nor as a commercial regulation to protect the private property interests of publishers, it was now presented by the Committee on Public Instruction as a mechanism for promoting and ensuring public enlightenment by encouraging and recompensing intellectual activity—that is, by granting limited property rights to authors:

Citizens, of all the forms of property, the least susceptible to contest, whose growth cannot harm republican equality, nor cast doubt upon liberty, is property in the productions of the genius. . . . By what fatality is it necessary that the man of genius, who consecrates his efforts to the instruction of his fellow citizens, should have nothing to promise himself but a sterile glory and should be deprived of his claim to legitimate recompense for his noble labors?[93]

Like the Sieyès proposal three years earlier, this law guaranteed authors, or those to whom they ceded the text by contract, an exclusive claim upon the publication of the text for the lifetime of the author plus an additional ten years for heirs and publishers. The Royal Administration of the Book Trade, which had registered the literary "privileges" of the Old Regime, was to be replaced by a national legal deposit at the Bibliothèque nationale, where all property claims were to be legally registered. The decree differed from the Sieyès proposal in one crucial respect: it gave no retroactive protection to the former holders of "privilèges en librairie" or "privilèges d'auteur." With the law of 19 July 1793, then, the cultural capital of the Old Regime was definitively remanded from the private hands of heirs and publishers into the public domain. Rousseau and Voltaire, like Corneille, Racine, and LaFontaine, had now too been dead for well over ten years. Thus, as Condorcet had dreamed, the authors of the Enlightenment, as well as those of the classical age, became the inheritance of all.

The severing of the clauses on literary property from their original context in the Sieyès proposal on sedition and libel, the deletion of the clause reaffirming current "privileges," the mobilization of authors, and the new stress on public enlightenment significantly transformed the political meaning and impact of the law. Initially part of a concerted moderate effort to reregulate and police the printed word and ensure publishers profits, the recontextualized clauses came to be viewed as a "declaration of rights," presented as a Jacobin effort to abolish the vested interests of inherited privileges, to consecrate the bearers of enlightenment, and to enhance public access to the ideas of the Enlightenment.

But the law did not resolve the epistemological tension between Condorcet and Diderot. Rather, it produced an unstable synthesis between the two positions. It drew upon a Diderotist rhetoric of the sanctity of individual creativity as an

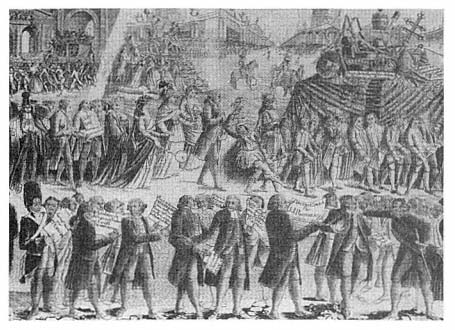

Figure 1.

The Revolution celebrated the author as a hero of public enlightenment rather than

as a private individual creator. A. Duplessis, La Révolution française , c. 1790, detail.

Photo: Musée de la Révolution française, Vizille, France.

inviolable right, but it did not rigorously respect the conclusions Diderot drew from this position. In contrast to the "privilège d'auteur" of 1777, the law did not recognize the author's claim beyond his lifetime but consecrated the notion that the only true heir to an author's work was the nation as a whole. This notion of a "public domain," of democratic access to a common cultural inheritance upon which no particular claim could be made, bore the traces, not of Diderot, but of Condorcet's faith that truths were given in nature and, though mediated through individual minds, ultimately belonged to all. Progress in human understanding depended not on private knowledge claims but rather on free and equal access to enlightenment. Authors' property rights were conceived as a recompense for the author's service as an agent of enlightenment through the publication of his ideas. The law of 1793 accomplished this task of synthesis through political negotiation rather than philosophical reasoning, that is, through a refashioning of the political identity of the author in the first few years of the Revolution, from a privileged creature of the absolutist police state into a servant of public enlightenment.