A Great Flow of Gas

The combined properties of Edward L. Doheny, the Mexican Petroleum Company in the northern fields, and Huasteca in the southern fields came to form the largest single oil interest developed during the great Mexican oil boom. Doheny's men in 1901 had brought in the first Mexican production at El Ebano, and in September 1910, they drilled the fabulous Juan Casiano No. 7 in the Golden Lane, which became the mainstay of the Huasteca company for nine years following its discovery. It would eventually yield a total of between eighty and eighty-five million barrels of crude, one of the single most productive wells in the world — after Potrero del Llano No. 4.[57] Based upon Casiano's initial production of 100,000 bd, Huasteca completed the pipeline to Tampico, made important sales contracts, began construction of a refinery at Tampico, and expanded its tanker fleet. It even supported the first efforts of Doheny to create a refining and marketing network of his own along the Gulf and East coasts of the United States. In appreciation, Doheny named his private yacht the Casiano.

Nonetheless, Doheny's lease-takers and drillers were not idle during the frenzied period of Mexico's oil development. They continued to explore and keep up with the competition in both the northern and the southern fields. Doheny did not speculate as heavily in the smaller leaseholds of the Pánuco, Tepetate, and Alazán districts. As one of the

early arrivals, he relied on developing the larger haciendas that he had purchased or leased in the final days of the Porfiriato. By 1911, the Doheny companies had acquired more than six hundred thousand acres of land, 85 percent of which was held in fee simple. They already had under contract haciendas that would later serve as new oil fields, such as Juan Felipe, Cerro Viejo, Chapopote Núñez, Zacamixtle, and Chinampa. But its properties in the northern fields were showing signs of anemia.[58] Salt water was showing already at El Ebano. No Doheny drilling crew ever ventured into the isthmus, which was El Aguila's domain, nor into other areas of exploration. Doheny's exploration concentrated now on the southern fields for one reason: Casiano crude yielded higher profits than did El Ebano crude. Geologist Ralph Arnold calculated that the heavier crude, more expensive to bring up and transport, made a profit of only five cents per barrel when sold at Tampico, while the lighter and easier to transport Casiano crude made Doheny's companies a profit of forty-one cents per barrel. As his field manager stated, "Topping Casiano oil you would get about 13% gasoline; from Ebano or Panuco oil, you would get 3 or 4%."[59]

Although Doheny was inclined to belittle the contributions of geologists, they nonetheless had helped him to establish a working geological model of oil exploration. Doheny had hired Stanford geologist Ralph Arnold and the former West Virginia state geologist I.C. White. Moreover, the most renowned Mexican geologist of the period, Ezequiel Ordóñez, had been an employee of the Mexican Petroleum Company since 1903. Ordóñez was instrumental in distinguishing between the oil exudes that indicated large underground accumulations of oil and those seepages that indicated isolated dissipations.[60]

Doheny, Ordóñez, and other Huasteca employees developed a hypothesis. The size of the surface oil pool was not crucial, nor did a bubbling oil seepage indicate that a sizeable oil deposit lay directly beneath. They concluded instead that the oil had collected in the underground crevices and caverns formed by old volcanic explosions that forced basaltic plugs up through the sedimentary strata. Therefore, the exudes found in areas of contact between basaltic plugs and the limestone were the most important indicators of oil. This was the case when Doheny's crews, advised by Ordóñez, had brought in production at the base of the Cerro de la Pez at El Ebano in 1903. Such low-lying hills were also found at the Huasteca properties of El Chapopote, Juan Felipe, Cerro Viejo, and Cerro Azul. The drillers would sink the wells on the largest fracture radiating outward from the plug.[61] This was the geological

theory that brought drilling crews to the hacienda of Cerro Azul in 1916.

As Doheny's Casiano well had made his company one of Mexico's largest, the Cerro Azul discovery would catapult his organization into one of international importance. Doheny had acquired the property of Cerro Azul, known for its numerous oil pools, as early as 1906. Huasteca delayed the development of this solid prospect. After the Juan Casiano discovery, other necessities intervened: the pipeline, market contracts, storage facilities, and the refinery. In addition, work crews built a narrow-gauge railway from San Jerónimo, a small port on the Tamiahua waterways, to Cerro Azul and numerous roads in order to transport equipment to the property. The first two perforations at Cerro Azul were begun in 1914. The third well, completed in 1915, yielded a continuous but minor flow of oil. Crews then sank Cerro Azul No. 4 "in the middle of a small esplanade," Ordóñez explained, "partly surrounded by hills, that is to say, a situation similar to that of the Casiano wells."[62]

Like many of the wells of the Faja de Oro, Cerro Azul No. 4 had "drilled itself in." Once the cable tools had struck through to a pocket of gas, the rush of gas out through the well casing tended to deepen the well to the level of crude oil.[63] The first emission of gas on the night of 10 February 1916 blew out the drilling equipment. It destroyed the derrick in the classic fashion of Mexican gushers. After seven hours, the transparent gas turned to black crude oil. The well ran wild for nine days. By that time, the well was exploding at the rate of 260,000 barrels per day, throwing a jet of crude oil three hundred meters straight up. When they finally placed a valve over the well and shunted its crude into a pipeline, the well head maintained a pressure of 1,035 pounds per square inch.[64] Such wells as the Cerro Azul did not need to be pumped. On the first day, the well flowed unchecked at 152,000 bd and by the fifth day, it was flowing at 160,858 bd.

News of the Cerro Azul discovery spread rapidly among competing foreign oilmen. J.B. Body reported to Lord Cowdray that the gas noise could be heard at El Aguila's Naranjos camp nearby.[65] Cerro Azul No. 4 made oil history for being the most productive shallow well ever. Its depth was 1,792 feet, or 1,351 feet below sea level in the nearby Gulf of Mexico. Its total production to 1932 had been eighty million barrels.[66] Cerro Azul No. 4 elevated Doheny into the position of largest producer and exporter of oil during the great Mexican oil boom. His company now surpassed Cowdray's El Aguila by a large

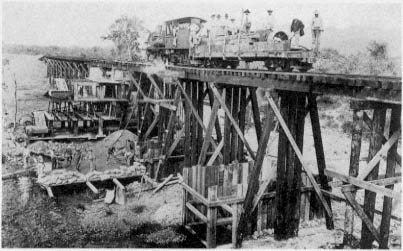

Fig. 7.

Bridge building near Cerro Azul. the Huasteca Petroleum Company

constructed a narrow-gauge railway to its new oil fields in the Golden Lane

in order to deliver equipment and supplies to its oil camps. Here, Mexican

laborers and their American supervisors complete the pilings of a railway trestle

over an arroyo. from the Eberstadt Photo Collection, courtesy of the Barker

Texas History Center at the University of Texas.

margin. But he also suffered the problems of flush production: how to transport the oil to market and how to sell it. To solve these problems, Doheny had to expand his operations outward from Mexico until he had created a multinational business enterprise.

The nightmare of every independent producer was to have discovered enormous quantities of crude petroleum with no means for transporting it to buyers — and then having no buyers. Doheny's discovery of Juan Casiano No. 7, followed within four years by Cerro Azul No. 4, placed Doheny in such a dilemma. He sold asphaltum and fuel oil in Mexico and also exported asphalt. But, being a Californian oilman, he had few outlets in the eastern United States. Nor, in September 1910, did he have the financial resources to rapidly develop the kind of infrastructure needed to transport the oil to tidewater and deliver it to refineries in the Gulf and Atlantic states. Therefore, his first phase of expansion entailed a simultaneous and desperate search for customers and capital necessary to build transport and storage. The second phase of expansion, commencing with the discovery of the Cerro Azul well,

propelled him into the development of his own refining and retail networks in the United States.

The first phase of expansion found Doheny quite successful in completing the pipeline from Juan Casiano to Tampico and in finding buyers. He secured the capital from a combination of independent Pennsylvania oil speculators and from a New York investment bank, William Salomon and Company. Apparently, the sum amounted to $12 million from Salomon.[67] The pipeline was completed in 1911. A terminal station and tank farm was constructed at Mata Redonda, on the southern bank of the Pánuco River opposite Tampico. Tank steamers anchored just three hundred feet from the nearest storage tank, one of thirty-five at the terminal's tank farm. The company owned twenty-two other large (55,000-barrel capacity) steel tanks elsewhere and numerous smaller storage facilities. On any one day in 1911, the company might have more than 2.5 million barrels of oil in storage, including earthen reservoirs. On the Pánuco River, Doheny operated three oil barges, a river steamer, and two steel freight barges. The latter would become increasingly important to deliver imported equipment from Tampico.[68] By 1917, nine tankers with a capacity of 60,450 tons were in the Pan American fleet, even though the United States had commandeered five and Great Britain one for wartime service. The English-made tankers (or "tank steamers," as they were sometimes called) were carrying crude oil from the Huasteca terminal at Tampico to U.S. ports from Texas to Massachusetts. His work gangs were also building the roads and rail lines through the Huasteca lowlands from Tuxpan to Tampico.[69] Although he borrowed capital to construct, quite rapidly, an impressive transportation infrastructure, Doheny still depended upon the big U.S. — based refining and marketing companies to buy his crude oil.

The Mexican market for petroleum came into crisis beginning in 1911. The fall of the Díaz government and the outbreak of revolutionary violence from Chihuahua to Morelos eroded Doheny's established markets for petroleum products. Mines shut down, railway tracks were breached, trains destroyed, and street paving stopped. Mexican Petroleum Company had had a contract with the Mexican Central Railway since 1905, since assumed by the National Railways, to buy 16,000 bd of fuel oil for a period of fifteen years. In order to compete on the domestic market with El Aguila, Waters-Pierce had stopped importing crude oil. It concluded a contract to take 2.5 million barrels of Huasteca's lightest crude oil from 1911 to 1915 for its Tampico refinery.[70]

Once the Revolution struck, the National Railways took less than half of what it had contracted to buy from Doheny. Even so, it was seldom able to pay cash for it. The Huerta government in 1914 and then Carranza in 1916 paid for fuel oil by giving Mexican Petroleum, and El Aguila too, certain tax credits instead of cash. The cessation of street paving motivated Doheny's men to carry on this business elsewhere. Harold Walker was in San Salvador in 1912 in order to make a bid for the paving of the streets of that Central American city.[71] None of these activities helped Doheny sell his new production.

For that, he turned to the large refining and marketing companies that dominated the U.S. oil market, especially Standard Oil of New Jersey. This must have involved some swallowing of pride for an independent oilman. Curiously, the new alliance between Doheny and Standard Oil now set Doheny against the interests of Jersey's former associate, Henry Clay Pierce. Early in 1911, E.L. Doheny had met with Jersey Standard's H.C. Folger, Jr., at 26 Broadway, New York. Standard Oil and Huasteca agreed to a five-year contract by which several of Jersey's refineries would purchase a total of two million barrels of oil per year from Mexico. Best of all, Jersey paid in advance, much to the relief of the Doheny organization.[72] For its part, Jersey Standard's move to deal directly with a producer of Mexican crude oil was its strategic reaction to the 1911 Supreme Court dissolution. In that decision, Standard Oil New Jersey, a refining and marketing giant, was separated from nearly all of its producing subsidiaries. Standard New York, Ohio, Indiana, and California were broken off, forming separate entities from Jersey. The Supreme Court also separated Standard from Waters-Pierce. Thereafter, Jersey Standard was free to develop refining and marketing in the Lower Mississippi Valley and Texas, previously part of the Waters-Pierce territory. Jersey was also free to move into Mexico.

Soon, tankers owned by Jersey Standard began delivering stocks of crude oil to the refineries of its new affiliate in Corsicana and Beaumont, the Magnolia Petroleum Company. What Mexican production Magnolia could not absorb, Magnolia sold off to other refineries and marketing companies from Texas to Missouri. Apparently, the contract enabled Doheny to draw on a $400,000 loan from the U.S. marketing company that Doheny used to develop his infrastructure in Mexico. The entrance of the Magnolia Company into the Texas market provided a very direct assault on the monopoly that Pierce had enjoyed in selling Standard Oil brands exclusively. Armed with inexpensive

Mexican crude oils acquired from the Huasteca Company, Magnolia's refineries began putting out Standard-brand gasolines, naphthas, and kerosenes at reduced prices. Magnolia's sales agents then began to undersell Pierce's products by as much as 20 percent. Pierce complained bitterly.[73] All this was, of course, of no concern to Doheny. He needed to sell a great deal of petroleum, and the Standard contract allowed him to do just that.