4—

What Makes Sausage-People Fight?

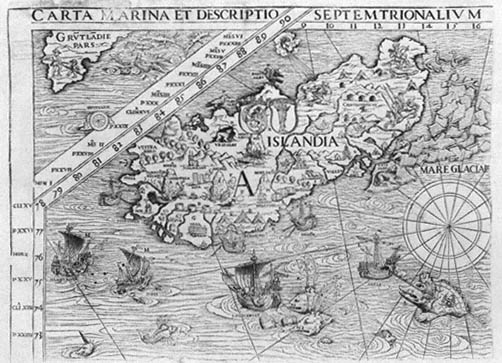

After the long wrenching, dismantling, and finally mythicizing movement of the Quaresmeprenant section, the two-chapter interlude in which Pantagruel kills a whalelike sea creature provides action-filled relief.[1] Alcofribas resumes his narration, and the Pantagruelians behave as they normally do: Friar John is brave, Panurge is cowardly, and Pantagruel dispatches the spouter with impossibly perfect marksmanship. The whale-monster is hauled ashore on Ferocious Island where some of Pantagruel's sailors carve it up "to gather the fat of its kidneys" — just as the inhabitants of one of the Faroe Islands are shown doing on Olaus Magnus's map (see Fig. 3). Faroe/Ferocious Island, we have already been told at the beginning of the episode, is the home of Farfelu Sausages.[2]

[1] Action-filled but not less richly symbolic: see n. 5 to Part Two and the references to Paul Smith's analysis of the physétère episode. Because the physétère appears immediately after Pantagruel recounts the myth of Antiphysie, and because Panurge at the approach of the sea-monster begins crying with fear, Smith comments: "Tout se passe comme si Panurge se laissait tromper par l'homologie phonique qui lie le physétère à Anti-physie." False or negligent etymology: the sea-monster's name, from Greek physeter, means "the blower"; a whale blows out water from its spout; conversely, when Pantagruel's arrows hit the monster in the right spots, the blower ceases to blow and is deflated. Hence, concludes Smith, "La victoire de Pantagruel sur le monstre peut se fire comme celle de l'Harmonie sur le Chaos, de I'Esprit sur la Matière, de Physis sur Antiphysie" (Smith, Voyage et écriture , 112, 116–17; see further 120–21). Such conclusions draw much metaphysics (and some hasty identifications of Pantagruel's significance generally) from a slight myth and its aftermath. But Smith, like Beaujour and Fontaine, juxtaposes his conclusions clearly to the text (see my ch. 3, n. 46). Smith, incidentally, identifies Quaresmeprenant in the traditional way with Lent (ibid., 120).

[2] QL, 29, 643. Farfelus, "zany," is Rabelais's punning neologism, forged to match Faroe/Farouche. Before Rabelais only fafelu existed, glossed in Le Petit Robert (Paris, 1978) as "dodu," well filled-out, puffy. The group of words is related to fanfreluche (see Rabelais, G, 1, 31), a bagatelle or light, floating thing (from Old French fanfelu , twelfth century, and fanfeluce , fourteenth century); see A. Lefranc, ed., Oeuvres de Rabelais, Volume 1 (Paris, 1913), 25, n. 48.

Rabelais's tripe-sausage tribes are a fusion of two groups described in a merry tale, anonymously published in 1538, called The Disciple of Pantagruel .[3] In The Disciple one group is called the Sausages (les andouilles ): they are "about twelve feet long . . . [with] sharp, biting teeth"; they feed in herds on the Tuquebaralideaulx Islands, "like cranes or sheep." The other group is called "the ferocious people" (les farouches ); they are "people who are hairy and colored like rats ," and they live in caves at the bottom of the sea. Like the Sausages, they have "long sharp teeth." In Rabelais's Fourth Book the Sausages live on Ferocious Island and behave something like the scampering rat-people in The Disciple . But they have lost their sharp teeth and have acquired slightly more civil — and much more Carnival-like — customs.[4]

Pantagruel, eating lunch with his friends on Ferocious Island, asks Xenomanes what kind of animals are climbing up a nearby tree, "thinking they were squirrels, stoats, martens, or weasels!' Xenomanes explains that they are Sausages, who are probably scouting to see if Quaresmeprenant has come. Rabelais's Sausage-people, then, seem at first to have the furry, small animal size of the Disciple 's ferocious people. They are just as unreasonably impetuous, too, as Xenomanes explains in giving an account of the latest stage in the war between them and Quaresmeprenant.[5]

Here is the place where Rabelais inserts references to the contemporary Protestant-Catholic war in Germany, clothing the actors involved in the traditional costumes of a Carnival-Lent combat farce: The "mountain Sausages" and "forest-dwelling Blood-puddings" (Saulcis- sons montigènes, Boudins sylvatiques ) who are fighting Quaresmeprenant represent those Protestant Swiss and south German allies against whom Emperor Charles V took the field in the 1540s. Quaresmeprenant, says Xenomanes, has refused to make peace with these confederates — as indeed Charles V refused to make peace with the Protestants in 1546.

[3] See ch. 2, n. 25.

[4] Demerson and Lauvergnat-Gagnière, eds., Disciple, 23–27. The considerable inventive talents of the anonymous author may also have served to supply Rabelais with some bizarre associations developed in the description of Quaresmeprenant and with some names used in chapter 40, the list of cooks who fight the fierce Sausages. See Disciple, 60–61 (critical apparatus), 74, 77 (critical apparatus) for references to these possible associations.

[5] Quotations concerning the introductory section about the Sausages and their war against Quaresmeprenant are from QL, 35, 656–58.

Alban Krailsheimer has pointed out, too, that Charles's well-known pious melancholy is similar to "the general idea of an unhealthy and gloomy monster" emblemized in Quaresmeprenant. But it would be a distortion to limit Rabelais's vast description to this particular meaning, just as it is illusory to expect to find historical referents for every symbol Rabelais uses in a context like this, especially in the case of those traditional to the Carnival-Lent combat theme like "Fort [Herring] Barrel" and "Brine-Tub Castle! In terms of contemporary French readers' perception of Rabelais's allegory, the mimesis of Carnival forms must have been more obvious than the political elements to all but the most internationally informed readers. Rabelais is as usual writing for several audiences here, one more political than others. The fact that the political dimension is there maintains the orientation to present-day events strongly affirmed with the references to Calvin, Postel, and DuPuyherbault.[6]

But does not Xenomanes's account of the current stage of the war with Quaresmeprenant reinforce the old idea, at least for a less political audience, that all this is only an allegory of Carnival fighting Lent? Such an implication is bound to disturb readers who have closely followed the descriptions of Quaresmeprenant. They have concluded that Quaresmeprenant is both more and less than Lent. Regretful disciple

[6] On the Swiss and Germans see Krailsheimer, "The Andouilles," 229. See also his 232: "What should be understood by the 'forteresse de Cacques,' which Quaresmeprenant refuses to surrender to the Andouilles? This . . . and 'le chasteau de Sallouoir' . . . were doubtless no mystery for Rabelais' contemporaries, and the violence of the language is surely provoked by some historical fact." If the "historical fact" can be found, its aesthetic integration and adaptation to the Carnival-Lent theme will appear all the more remarkable. Rabelais also vents his spleen against the Council of Trent in this chapter, referring to it obliquely in QL, 35, 658, as the "National Council of Chesil" (i.e., "Kessil," Hebrew for "fool" or "nitwit"): At this Council the Sausages, Xenomanes reports, were bullied and Quaresmeprenant too was threatened with denunciation as a "filthy, broken-down stockfish" if he should come to any agreement with the Sausages — all of which allegorizes nicely the Tridentine stiffening of Protestant-Catholic differences. As Robert Marichal has shown (cf. ch. 3, n. 20, above), Rabelais was especially well informed about the circumstances surrounding the Smalkaldic War and the negotiations of imperial moderates both at Trent and elsewhere with the German Protestants; he may himself have been used by Cardinal Jean du Bellay as an envoy to representatives of the German Protestants in Metz in 1546–1547. See Marichal, "Rabelais et les censures," 138–41, for the diplomacy, and 146–47, for some passages in the first edition of the Fourth Book influenced by this involvement.

of churchly injunctions, he is a pitiful invalid, sickened by contradictory allegiances. He is also the enlarged image of unnatural behavior, a paradigmatically powerful figure who represents not simply the ill wisdom of observing Lent's prescriptions, but its looming, terrifying inhumanity.

What then do the Sausages represent? Rabelais has already suggested that they, like Quaresmeprenant, do not incarnate Carnival; the role of incarnation seems to belong to their "protector and neighbor, the noble Mardi Gras."[7] The author thus frustrates readers' attempts to establish the allegorical identity of the Sausage-people just as he earlier did their attempts to categorize Quaresmeprenant. Delaying clear narrative meaning in this way is dangerous. Readers may become so exasperated that they abandon the text because it so frequently directs their attention away from a linearly unfolding narrative that would carry them from an intriguing beginning to a satisfying end. The second half of the Carnival-Lent episode seems explicitly designed to court this disaster. Narrative progress here, even more than in the long lists describing Quaresmeprenant, is repeatedly deferred. In the first half the narrative seemed to grind to a halt as the symbols piled up. But even though in the second half direct action is equally in suspense, the narrative in this case gathers energy and dynamic thrust through the deferral of action because the delaying conversations of the Pantagruelians circle around and toward a coming battle.

The first delay occurs when Xenomanes recounts the past history of war between Quaresmeprenant and the Sausages, after Pantagruel sees some of the latter scampering up a tree. No sooner has Xenomanes finished than Friar John intervenes to say: "There'll be some asinine goings-on [de l'asne ] here, I can see that! Those venerable Sausages may be taking you [Pantagruel] for Quaresmeprenant." Xenomanes seconds Friar John's warning with a pseudo-proverb: "Sausages are sausages, forever double and treacherous."[8] With the latter silliness we are launched in the same direction as that developed with Quaresmeprenant, the Renaissance impulse to associate bodily with mental and emotional traits: such greasy, slippery tripe-people, who have furry hair and quick scampering movements like weasels, must be full of deceit.

I have translated Friar John's phrase "Il y aura icy de l'asne" in a

[7] The statement is part of the first description. See ch. 3 above.

[8] Quotations about the second and following delays are from QL, 36–40, 658–72.

minimal although still metaphorical manner. De l'asne, "some donkey" or "something of a donkey kind," is enigmatic. Did it mean behaving in a silly or obstreperous way, as in the English colloquial "horsing around"? Did Friar John, always the warrior, imagine some carnivalesque battle like those occasionally occurring on mardi gras between men in animal masks[9] The butchers in fifteenth-century Nuremberg danced through the streets led by a hobbyhorse, hobby-donkey, hobby-ram, and hobby-unicorn. Did they, like the much later documented "Old Hoss" at Padstow, England, or the "Pony" at Pezenas, France, turn boisterous and belligerent, charging upon spectators? At Hof, Germany, in 1566 the butchers, led by a man dressed in raw oxhide and horns, ran and danced their way through the streets on Thursday after mardi gras, waving clubs and ringing cattle and sheep bells. Falling upon some textile workers who wanted to pass through the streets before them, the butchers drew knives and wielded their clubs. The textile workers pulled up paving stones. In the end one of the latter was killed.[10]

Rabelais's Sausage-people are like these revelers, half-animal, and bellicose. Wildmen in Carnival did not always pounce upon others. One has the impression that at Nuremberg they were objects of spectacle more than vehicles of aggression. Whether dancing about or wielding their clubs, however, they represented irrational, unpredictable behavior, and in this sense they were akin to the fool maskers in cap and bells.[11] Foolishness, wildness, and arbitrary assault are all illustrated by the Sausages in the Fourth Book . But their bodily shape and

[9] Huguet, Dictionnaire, s.v. "âne," finds only one other sixteenth-century use of the phrase "de l'asne"; it occurs in d'Aubigné's Baron Faeneste . Huguet concludes lamely from both Rabelais's and d'Aubigné's usage that it meant "something bad, a battle, some blows."

[10] See Kinser, "Representation," 2, for illustration of the hobby-animals in the Nuremberg butchers' dance of 1449. Violet Alford, The Hobby Horse and Other Animal Masks (London, 1978), 36–43, describes the two-man "Old Hoss" of Padstow, which has allegedly been charging into crowds and covering victims with oil and soot since the early nineteenth century. Alford, 94, also provides a brief description of the wooden-frame Poulain of Pezenas, France, documented since 1702 and usually carried by more than two men. For Hof in 1566 see Enoch Widman, Hofer Chronik, in Quellen zur Geschichte der Stadt Hof, ed. Christian Meyer (Hof, 1894), 202–3. The continuation of Carnival into officially Lenten days (here the Thursday after Ash Wednesday) was not unusual in some German locales for complex historical reasons. It was not considered an impiety but simply an age-old practice.

[11] This fight is briefly described in ch. 2. Kinser, "Presentation," 9, includes a representation of the 1539 scene with fools and wildmen running about.

texture make their belligerence laughable: andouilles were sausages made from tripe and other fatty portions of the pig, cut in narrow strips, seasoned, and stuffed into a portion of pork intestine that had a phallic length and figure.[12] Constructing his protagonists in this way gave Rabelais a wide range of registers on which to draw, all of them characteristic of Carnival behavior and carnivalesque talk, with their emphasis on the irrational, emotionally dominated "bodily lower stratum," alimentary, intestinal, animalistic, and choleric, always ready to fight.[13]

The carnivalesque overtones to the name and character of the strange residents of Ferocious Island frame the conflict between them and the Pantagruelians. They are the text's festive context, supporting it more consistently and fundamentally than either politicoreligious references or the parodic literary allusions to epic warfare that emerge later in the episode. Rabelais interweaves one series of metaphors with another by means of this festive context.

From the Middle Ages, andouille and its equally boneless, slippery phonetic cousin, anguille (eel), referred in popular parlance to the penis.[14] Rabelais uses their similar sound to conflate the two phallic symbols, as Barbara Bowen has shown in a perceptive study. He conflates them by drawing on the derivation of anguille from Latin anguis (snake). The narrator Master Alcofribas explains sententiously that "the serpent who tempted Eve was Sausage-like" (le serpens qui tenta Eve estoit andouillicque ).[15] The eel-like undertone to the Sausages brings out the slipperiness that makes them "two-faced and treacherous," as Xenomanes says. They are lively, sexy little creatures but not to be trusted.

[12] J. M. Cohen's translation of andouilles as "Chitterlings" (Gargantua, 524) is hence incorrect, at least with reference to the present-day American meaning of chitterling. The translation has been repeated in all English translations since the first one by Pierre Le Motteux (1694); perhaps in his time and place it was correct.

[13] See Bakhtin, Rabelais, 23, on the carnivalesque use of references to the bodily lower stratum.

[14] See the examples in R. Howard Bloch, The Scandal of the Fabliaux (Berkeley, 1986), 52; Bowen, "Lenten Eels," 19, offers other examples.

[15] QL, 38, 665. Bowen, "Lenten Eels," 20–21, makes the point about Rabelais's implied association of Latin anguis with French anguille . The andouille/ anguille association may have been suggested to Rabelais from Le Disciple de Pantagruel, 50, which associates the two in passing; Bowen, "Lenten Eels" 18, also notes this reference. But the Disciple is not concerned with Carnival-Lent distinctions, so the reference does not carry the same associations as those in Rabelais.

The Latin root of andouille lends further support to these associations with eels: inducere means to put one thing into another, as is done in the manufacture of these sausages; inducere also means to lead one thing to, toward, or into another, and hence, metaphorically, to insinuate.

But all these verbal and proverbial associations do not mean that Rabelais is conflating the festive meaning of eels and sausages, nor that he suggests that Carnival and Lent themselves were becoming less ideologically distinct.[16] On the contrary, the larger context of this verbal play, the context that from the beginning of the approach to Quaresmeprenant leads readers to look for embroidery on the theme of Carnival-Lent opposition, insures that the difference between meaty Carnival food and Lenten fishy fare hovers over every mention of one or the other, pulling them apart in readers' minds even as the text pushes them together.

In a similar way Rabelais plays tantalizingly with readers' knowledge that as carnivalesque fare the Sausages should be eaten. In the nearly twenty octavo pages dealing with these juicy morsels, Rabelais never allows their ingestion. "Sausages will be sausages," Xenomanes declares. At the level of text, they are everything but that. Their alimentary dimension is suspended over the text, all the more hilariously.

Given the ribald associations brought by readers to any mention of sausages, the first direct view Pantagruel obtains of the Sausage-people en masse is a marvellous inversion of expectations. Just after Friar John's prediction of donkey business, Pantagruel jumps up to discover "a large battalion of huge and mighty Sausages marching toward us to the sound of bagpipes and flutes, sheeps' stomachs and bladders, pipes and drums, trumpets and clarions." Here come the same creatures who have been described up to now in small and sinuous terms, decked out as heroic fighters and marching uproariously along to sheep-bladder music. Did this idea too derive from Rabelais's perusal of Magnus's delightful map? There is a bagpipe player just above the whale being carved up on the Faroe Islands in Figure 3. Or is this one more reminiscence of Carnival spectacles? These are Carnival maskers, making rough music. "Their orderly movement, their proud step and resolute mien convinced us that these were no small fry [Friquenelles]"[17] The

[16] See ch. 2, n. 24, on Bowen's conclusions.

[17] QL, 36, 659. Boulenger, the editor, notes that Friquenelles also meant "femmes galantes." Because Xenomanes has said earlier that all Sausages are women, their transformation into fierce fighters is all the more comical. Note the picture of a similar marching squadron of colorfully costumed pikemen with wildmen and fools gaily mingled among them in the Schembart parade of 1539 at Nuremberg reproduced in Kinser, "Presentation," 9, figure 2. On the "rough music" typical of Renaissance Carnival celebrations, see e.g., C. Marcel-Dubois, "Fêtes villageoises et vacarmes cérémoniels, ou une musique et son contraire" in Les Fêtes de la Renaissance, Volume 2 (Paris, 1975), 602–16.

low is mockingly portrayed as the high, as an army of well-disciplined fighters, as worthy of respect as would be any armed assembly of the nobility of Rabelais's day, whose claim to high estate was based on prowess in battle. In spite of this evidence of imminent attack, a second delay ensues similar to that which occurred after the Pantagruelians arrived on the island and Xenomanes recounted the latest incidents in their war with Quaresmeprenant. Pantagruel calls a council of his advisers, with which he discusses Greek, Hebrew, Roman, and modern French parallels to the uncertain situation in which they find themselves.[18]

It happens that among Pantagruel's followers are two soldiers named Riflandouille and Tailleboudin, "Maul-Sausage" and "Chop-blood-pudding." Pantagruel, taking this as an omen of victory, occasions a third delay by discoursing upon the prophetic properties of names.[19] As in the case of the preceding delay, during which Pantagruel speaks learnedly about affairs that have no practical bearing upon the matter at hand, the abstruse and superstitious absurdity of Pantagruel's examples proves to the reader the opposite of what Pantagruel proves to his listeners. These speeches occupy the same place in Rabelais's plot as the idle discourses of Carnival or Lent to their counselors in the traditional farces and narrative poems, just before the fatal invasion of the opponent. One side or the other in the combat schema is signaled to the reader at an early point as the eventual loser because of its vain activities and inattention to military preparation. In Rabelais's story, of course, these indications are belied. Although Pantagruel is portrayed as a wooly-headed carnivalesque leader, spouting classical copia at the most inopportune moments,[20] he is also shown taking proper precau-

[18] QL, 36, 659–60.

[19] QL, 37, 661–64. Calcagnini, whose work Rabelais used for the myth of Anti-Nature, was also the source of the stories of prophetic names, as Boulenger points out, 644n.

[20] Copia, rhetorical copiousness; how to achieve it was a favorite topic of Renaissance humanists. The best-known handbook, familiar to Rabelais, was Erasmus's De duplici copia verborum ac rerum .

tions. All this is in consonance with another literary signal repeated in this part of the Carnival-Lent episode, mockery of the epic style. In the Iliad and the Aeneid leaders also take counsel and omens before entering battle. Pantagruel is a garrulous revivification of the heros of antiquity, a comic mirror of contemporary humanist ideals. Having concluded his discourse on names, he stirs up his two commanders' courage and gives them "mardi gras" as the password to be used in mounting guard. With the latter term Pantagruel assumes the mantle of Carnival for the coming fight. But why, then, are they fighting the carnivalesque Sausages, and why are the Sausages fighting them?

Rabelais has reached the high point in his dismantling of the traditional roles. After creating a personage carrying the usual name applied to Carnival, whose whole horrid force is devoted to traveling toward Lent, after sketching what seems to be the epitome of carnivalism in the Sausages, here come the Pantagruelians to take over the role of champions of Mardi Gras against the "treacherous" enemy. "You are making fun of me here, boozers! You don't believe that it was all in truth just as I have recounted it. I really don't know what to do about you. Believe it if you wish; if you don't, go see for yourselves. But I know what I saw. It was on Ferocious Island. I give you its name."[21] This marvellous turn of the narrator to what appears to be a set of auditors, not readers, refreshes the frame of oral narration that enters and exits from the Rabelaisian books in erratic counterpoint with the conventions signaling written discourse. The comic insistence of Master Alcofribas on the rule of eyewitness unimpeachability is patterned on the similar affirmations of Lucian in A True History . Lucian wrote his book in parody of Hellenistic historiography, in which it had become conventional to parade one's veracious closeness to the facts to be narrated, only to follow such principled beginnings by accounts of famous battles with invented speeches and sententiously fictitious discussions of strategy by the leaders. The habit was revived by fifteenth-century humanist historians like Bruni, Poggio, Giovio, and Polydore Vergil. Alcofribas's interruption, a parody of Lucian and perhaps also of these modern imitators of Lucian's targets, adds emphasis to the mockery of Pantagruel's pursuit of epic propriety.

Oral, apostrophic style — short sentences, direct address, personal af-

[21] QL, 38, 665.

firmations, references to familiar time and place[22] — is maintained through chapter 38. But this fourth delay also introduces another shift in the fictive context. The Sausages are removed from the humble half-animal, half-alimentary contexts that served first to define them and are grotesquely draped in the finery of myth. The giants who piled Ossa on Pelion were half-Sausage in race, "good master Priapus" is nothing but a "transformed Sausage," the serpent tempting Eve was a Sausage, and so on. This mythologizing passage, which offers a noble pedigree to the Sausages, serves as a transition to the fifth and final delay before the battle.[23]

In chapter 39 written narrative style is resumed. Friar John argues, invoking classical and biblical parallels, that he and his cooks should fight the battle. Pantagruel agrees, although he later himself participates in the combat. Friar John addresses his subordinates as young knights about to win their spurs in battle. The Iliad 's Trojan horse episode is imitated, except that the cooks hide inside a war machine designed not like a horse but a sow.[24]

The words Troye (Troy) and truie (sow) are phonetically and graphically close in French, which is comic enough. But there are several other aspects to the joke. Such a war machine was used against the English by King Charles VI in the Hundred Years' War, so Master Alcofribas recalls.[25] Thus at the mock epic level of narrated action, Alcofribas asserts the authenticity of the absurd by historicizing it. Alcofribas also offers technical details that make the Pantagruelians' war engine seem the more real.[26] At the reader's level the reference appeals to

[22] See, e.g., QL, 38, 665: "Si ces discours ne satisfont à l'incredulité de vos seigneuries, praesentement (j'entends après boyre) visitez Lusignan, Partenay, Yovant, Mervant et Panzauges en Poictou. Là trouverrez tesmoings vieulx de renom."

[23] The grammatically ambiguous title to this chapter also helps shift the Sausages from low animal toward high human estate: "Comment Andouilles ne sont à mespriser entre les humains." "Among humans" in the phrase, "that Sausages should not be despised among humans," may be understood either as the human audience whom Alcofribas addresses in this chapter or as the human species to which Sausages, for all their divine and animal affiliations, are considered in this chapter to belong.

[24] Marcel Tetel, Rabelais (New York, 1967), 71–73, indicates the points of mock heroic style used in this section.

[25] The reference is correct, according to Boulenger, QL, 40, 668: Froissart recalls the use of such a "sow" in the siege of Bergerac in 1378. The king in question was Charles V, however, not Charles VI.

[26] QL, 40, 668: "C'estoit un engin mirifique, faict de telle ordonnance que, des gros couillarts qui par rancs estoient autour, il jectoit bedaines et quarreaux empenéz d'assier."

French pride in an English defeat during the Hundred Years' War. At the authorial level — that is, from the point of view of the author's representational activity — there is gentle irony about the manner in which the great victory over the English was won, with an iron pig. But the dominant level of signification is neither nationalistic nor mock-epic but popular-cultural. Erasmus notes in the Adagia that the phrase "Trojan pig" in "common parlance" — presumably in antiquity — meant a hog stuffed with all manner of living things, "just as the Trojan horse sheltered armed men."[27] Did the idea live on through medieval times? Was it combined in some manner with the Biblical story of Jonah living inside a whale? Whence derives that other spouting creature in Magnus's Carta Marina, northeast of the Faroe Islands, which looks for all the world like a seagoing wild boar (see Fig. 4) with two cooks inside its belly, tending a pot over a fire? In the sixteenth century as in antiquity the sow continued to be a symbol of fecundity just as it was a source of succulent nourishment. Rabelais combines ancient and modem popular-cultural meanings of the pig as womb-rich and men-sheltering and gives them a carnivalesque turn: the sow will be stuffed with food stuffers who will fight stuffed Sausages.

The comic idea of conflating juicy pig meat with hard fighting men had already been used in the Carnival-Lent literary genre before Rabelais. In the Marvellous Conflict Between Carnival and Lent, a French narrative poem published sometime between 1500 and 1530, Carnivals' forces are led by "noble and courageous pigs!" Here the idea is simply to symbolize Carnival by means of its most eminent food. In Rabelais's story, where Pantagruel's forces are led by "gay and noble cooks:" the symbolic support of Carnival is less a category of food than the body's relation to food.[28] Listing the warriors' names is like declining the forms of a gourmand's fancies.

The names also describe the decline — comically — of these noble

[27] Desiderius Erasmus, Adagiorum Chilias quatuor, reprinted in Erasmus, Opera omnia, Volume 2 (Leyden, 1703), 1176 (Centur. 10, Prov. 70): "Gulae veteres architecti et hoc commenti sunt, ut bos aut camelus totus apponeretur, differtus intus variis animantium generibus. Hinc et porcus Trojanus venit in populi fabulam, cui hoc nomen inditum est, quod ita varias animantium species utero tegeret, quemadmodum Durius equus texit armatos viros."

[28] Cf. "Merveilleux Conflit," 121, with QL, 40, 672.

4. Section A of illustrations, Olaus Magnus, Carta Marina. Piglike Sea Monster near Iceland,

north of Faroe Islands. Bayer. Staatsbibliothek, Munich.

fellows from the estate of warriors to that of greasy, clumsy kitchen help.[29] There are, for example, Sousecod, Porkfry, Master Dirty, Fatguts, Greasypot, and Swillwine. Then come a plethora of stuffing cooks and sauce cooks whose arts are indicated by their names, and some thirty bacon makers, plus Freepepper, Mustardpot, Greensauce, "and Robert, who invented sauce Robert ." In a third category are names full of kitchen humor, incarnating the praise-abuse combination characteristic of that carnivalesque mode of humor in which "all names tend to extremes."[30] So we are introduced to Blowguts and Tasteall, Smuttynose and Widebeak, Shittail and Smartster, Stickyfingers and Begging Bag, Coxcomb and Tittletattle. Rabelais's 161 names zigzag between physiological and psychological attitudes to food. They play with people's relation to nourishment rather than, as in the medieval farces, with food's relation to the ceremonies of Carnival.[31]

This lengthy final delay to the action, while the names are listed, effectively eliminates all reason for the old Carnival-Lent tradition's denouement in battle. The Pantagruelians and their opponents obviously belong to the same side, except from the culinary point of view. And so the words of Gymnaste, Pantagruel's herald, do no good, when he bows to the advancing enemy and loudly proclaims: "We . . . are at your service. We all hold [fiefs] from Mardi Gras, your old ally."[32]

When the fighting does come, it is over in a narrative twinkling,

[29] Glauser, La fonction du nombre, 147, makes this point. The idea may have been developed by Rabelais from the basoche Carnival play to which we have referred, the Battle of Saint Pansard (1485), where Charnau's soldiers are Roasting Cook, Pastry Cook, Tripe-Stuffer, Egg-Cook, Butcher, and Scorching Cook (Deux Jeux de Carnaval, 16–17). The list of cooks is in QL, 40, 668–72.

[30] Bakhtin, Rabelais, 460–63.

[31] There are exceptions in the list, harking back to the medieval farces' personification of foods proper to Carnival: Goatstew, Pancake, Doughnut, Pigs-liver. There is also a small group of names referring to physical "deformities": Scarface, Bignose, Hairy Prick, etc. See Lazare Sainéan's rather heterogeneous division of the list into eight categories, La langue de Rabelais, Volume 2. (Paris, 1923), 477–83.

[32] QL, 41, 672–74, recounts the battle. In a feudal context like that depicted here, Gymnaste's words, "Tous tenons de mardi gras, vostre antique confaedéré" (italics added), are tantamount to affirming that the Pantagruelians owe homage and fealty to a lord named Mardi Gras. Perhaps Gymnaste asserts that the Sausages owe Mardi Gras homage and fealty also: "Tous" is ambivalent; it might refer to all the Pantagruelians or to Pantagruelians and Sausages. But the word confaedéré, ally, was more likely to be used between sovereign equals than between feudal unequals, and the rhetoric of the phrase seems to contrast "[nous] tenons " with "vostre . . . confaedéré ."

consisting of a mere thirty fines of text. The battle is a pell-mell free-for-all, like the rough-and-tumble fights on mardi gras by youths in rival village or town districts.[33] Pantagruel cracks Sausages over his knees,[34] and Friar John's soldiers jump out of the sow with dripping pans and cooking pots, wreaking havoc. All the Sausages would have died "if God had not intervened, goes the tale:"[35]

Out of the north a "great, grand, gross gray pig" came flying. It had wide wings like the arms of a windmill, with crimson pink flamingo feathers. Its eyes were flashing and red, like great carbuncles: its ears were green and its teeth topaz yellow. The tail was long and black, like lustrous marble; the feet were webbed and diamond-transparent. Around its neck was fastened a gold collar inscribed with the words hus Athenan written in Greek. This means "a pig teaching Minerva," adds the narrator.[36] The pork bird dropped mustard on the battlefield and flew off screaming "Mardi gras, Mardi gras, Mardi gras!"

The Sausage-queen explains to Pantagruel that the flying pig is the "tutelary deity" of the Sausages in wartime, for it is the "Idea" of "Mardi gras?" The word Idée is capitalized; it is glossed in the "Brief Clarification" with respect to Rabelais's earlier use of it in the Fourth Book: "invisible species and forms, imagined by Plato."[37] Ironic reference to Plato's concept of heaven-dwelling forms, which are the archetypal patterns for low earth-bound existences, is reinforced by the queen's further qualification of this anything but airy and spiritual pig-god as "the first founder and original [pattern] of the whole Sausage race." If this ideal form looks like a pig, that is simply "because Sausages are extracted from pigs."[38]

[33] For instance, at Nuremberg or Hof.

[34] Bowen, "Lenten Eels," 20–21, documents the phrase "rompre l'anguille" from 1509 onward as a comic proverb describing something impossible. Rabelais in 1552, like Noël du Fail in a work written only three years earlier, transfers the proverb to andouilles . Ch. 41, "Comment Pantagruel rompit les Andouilles aux Genoulx" gives prominence to this play with the proverb.

[35] Tetel, Rabelais, 82, points out that divine intervention again mocks a usual feature of knightly epic.

[36] This classical adage is given in Erasmus, Adagia 1:1, 40.

[37] Cf. BD, 761 (a reference to QL, 2, 565). The anonymous "Brief Clarification" is not always a helpful guide to Rabelais's usage, but it has the advantage of being contemporary, reflecting the reactions of a reader in the publishing ambience in which the author moved. It was added to some, not all, copies of the first editions of Rabelais's Fourth Book . See also Appendix 3.

[38] QL, 42, 676: "Elle respondit que c'estoit l'Idee de Mardigras, leur dieu tutéllaire an temps de guerre, premier fondateur et original de route la race andouillicque. Pourtant sembloit-il à un pourceau, car Andouilles feurent de pourceau extraictes."

Friar John's Trojan Pig has been raised on high. The apparition confirms Gymnaste's cry: we like you owe homage to Fat Tuesday, for we are as loyal to the idea of mardi gras as you. But while the Sausages drop their weapons and raise their hands "as if they adored it [the pork bird]," Friar John and his men go on "smiting the Sausages and sticking them on spits" until Pantagruel gives orders to stop.

The pig has a heavy, hard body like Friar John's metal sow. Its limbs and organs of sense are like gems, like some glittering Biblical idol; one notes that the queen of the Sausages has a Hebrew name, Niphleseth, the language of the Chosen People. The pork bird is at once ugly and spectacular, one more comically riveting image in the series of strange visions the Pantagruelians have seen and will see in the Fourth Book .[39]

To worship heavenly pig is just what one would expect of the spirit of Carnival. What wisdom does this pig have to teach Minerva? Simply that in Carnival time the stomach instructs the head, the low dominates the high, and earth pretends to be heaven, screaming "Mardi gras!" and flying through the air like some noble Pegasus.[40]

The lighthearted audacity of this parody of misguided piety is astonishing. The mustard the pork bird casts down upon the slain Sausages on the battlefield "resuscitated the dead," for it was a "celestial Balm" indeed a "Sangreal." As Edwin Duval has recently shown, Sangreal seems to be a Rabelaisian invention, suggesting simultaneously Holy Grail (San Greal, more usually Saint Graal) and real blood (sang réel ): both the holy chalice from which Christ drank symbolically consecrated wine at the Last Supper, founding the mystery celebrated in the Eucha-

[39] Revelation 4:3, in addition to the Old Testament examples, conserves this gemstone concept of divinity with John's vision of Jehovah on his throne: "And he who sat there appeared like jasper and carnelian, and round the throne there was a rainbow that looked like an emerald." Was Rabelais influenced in his imagination of a pork bird deity by the Hebrew studies of which so many proper names in the Fourth Book give evidence? On this new importance of Hebrew in the Fourth Book see Screech, Rabelais, 391–92.

[40] Pegasus is to Trojan horse as pork bird is to Trojan hog? Elizabeth Chesney, The Countervoyage of Rabelais and Ariosto (Durham, N.C., 1982), 89–90, suggests the Pegasus parallel to the pork bird, though not the rest of the equation. Chesney, 85, concludes more generally that Rabelais "blurs lines of demarcation [that is, the pig and its worshipers the Sausages]." Although she does not question the traditional identification of Quaresmeprenant with Lent (ibid., 82), she does emphasize the monster's internalized ambivalence.

rist, and the transformed wine of that sacrament, the very blood of Christ by which the Christian believer is resuscitated and saved.[41] Very lightly, very obliquely, Rabelais touches one of the most disputed points in early sixteenth-century theology: the doctrine of a saving immaterial grace mysteriously imparted by the "rear" material "presence" of sacrificial "blood." Protestant reformers attacked the doctrine as an "idolatrous," "judaic" remnant of pre-Christian sacrificial practices, which ruined true faith.[42] It seems something less than an accident, therefore, that the Sausage-queen with a Hebrew name is the one who explains the "Sangreal" mustard to Pantagruel. The gross and gleaming character of the pork bird idolatrously adored by the Sausages disguises this satire of Catholic doctrine by means of its apparently appropriate excess, its perfect adaptation to the surface theme of Carnivalesque inversion.

The Sausage-people are strange beings. They are religiously hideous. They worship in the pork bird an image that in the classical adage to which the Greek words on its collar refer is one of ignorance and inca-

[41] Edwin Duval, "La Messe, La Cène, et le Voyage sans Fin du Quart Livre, " Etudes rabelaisiennes 21 (1988): 135–36, establishes the referents to which Rabelais's sangreal pertains. There is another earlier allusion to the word which Duval has not noted. In a letter of 1542 (see ch. 5, n. 22), Rabelais refers to the bons vins being kept for his friend's coming as sang gréal . Here the word is divided into two words and the "g" is double, making the word gréal closer to the frequently attested spelling graal (grail) and further from Duval's réel (and/ or royal, as Duval also suggests). On the other hand, dividing sang from gréal places sang further from the familiar sain(c)t (holy), so often employed by Rabelais. Rabelais is writing in a loose and easy manner here; there can be no question of a serious, surreptitious attack on Eucharistic doctrine. However, he playfully invokes religious language at several points, and he uses literary language and allusions further developed in his novels. Among other things he signs the letter of 1542 with what might pass for an allusion to Alcofribas's profession as Pantagruel's cupbearer ("Vostre humble architriclin, serviteur et ami. François Rabelais, médicin"). I am inclined to think that this is an early articulation of the religio-literary neologism Duval has explicated, a neologism charged with satiric point from its eventual placement in the Sausage chapter. I disagree with Duval's explication only insofar as he makes this verbal play part of a consistent anti-Catholicism and indeed a surreptitious Protestantism, carried on from chapter to chapter and book to book (see Duval, ibid., 141, his conclusion).

[42] Contemporary Protestant attacks on the Eucharist and the Catholic liturgy generally as idolatrous and judaizing are reviewed, ibid., 133–35. Erasmus's more cautious criticisms of the same kind are also indicated, an important link to Rabelais, whose ideas resemble those of Erasmus in so many respects.

pacity for learning, an "Idea" simply of great, gross eating.[43] They are like savages; indeed they are very much like those New World savages described by European travelers as a population indigenous to strange and wondrous islands in the north and south Atlantic seas. They are innocents, scampering about like squirrels and martens, "always double and treacherous" because they follow no rules.

Facing such barbarians, Pantagruel and the Pantagruelians do not let their common allegiance to a distant Mardi Gras interfere with their identity as Europeans. Like Cortez in Mexico, like Pizarro in Peru, like Raleigh in Guinea, they offer fair terms of greeting, but, when the natives resist, they annihilate them.[44] After the battle is over, a different political parameter intervenes. Unlike the medieval Carnival-Lent tales in which the feudal princes Lent and Carnival are merely the first and most honored among many powerful princes and vassals, from the sixteenth century onward the political context woven into the genre is monarchist, assuming a radical difference between sovereign and subject. Pantagruel negotiates peace with the queen of the Sausages, who possesses enough authority over her subjects so that she can offer without ado to ship him 78,000 "royal" Sausages each year to "serve" him during the first course of his meals. (Even here the reference to ingestion remains unspoken!) Master Alcofribas takes care to specify other terms of the proffered peace, which include the queen's becoming Pantagruel's vassal for herself, her successors, and all her subjects in the island. But Pantagruel graciously refuses the homage and pardons the

[43] See the demonstrations of the "progressive devalorization of the alimentary theme in the Fourth Book " in Michel Jeanneret, "Quand la fable se met à table," Poétique 54. (1983): 163–80, and Jeanneret, "Alimentation, digestion, réflexion dans Rabelais," Studi francesi 27 (1983): 405–16, particularly 409, concerning the pig and its ignorance as connected with eating. Jeanneret is only concerned with the Carnival-Lent episode in passing, but his comments on it are acute and subtle, directing attention to the relevance of traditional Carnival-Lent combats and emphasizing Rabelais's negative presentation of both Quaresmeprenant and the Sausages. Like Alice Berry's "'Les Mithologies Pantagruelicques': Introduction to a Study of Rabelais' Quart Livre ," PMLA 92 (1979): 471–80, Jeanneret emphasizes the generally darkened and negating tone of the Fourth Book, as compared to Gargantua and Pantagruel .

[44] I am arguing not that Rabelais consciously satirized the beginnings of European colonialism but only that it existed as part of the general context of the tale. (Other islanders in the Fourth Book, almost as savage in behavior and certainly as strange, are not annihilated.) See on this point the collection of innovative studies in First Images of America: The Impact of the New World on the Old, ed. Fredi Chiappelli (Berkeley, 1976).

Sausages' aggression. The recent quarrel is expunged by introducing the forms of an idealized monarchic feudalism, in which two sovereigns treat each other as equals and dispose freely of the life and limbs of their followers. Because the two princes in question are idealized and the context is comic, everything turns out for the best. Even the shipped-off Sausages, although they "died" through lack of mustard, were honorably buried at Paris (there is a comic reference to the Rue Pavée d'Andouilles in the Latin Quarter, the modern Rue Séguier).[45] As is suitable in the case of a ritual opposition, where the purpose of confrontation is to mollify differences by expressing them, the very last word of the last chapter of the Carnival-Lent episode refers to the alimentary symbol to which both sides give allegiance, however different the style: "Pantagruel retired to his ship. All his good companions did the same with their arms and their sow."

[45] Quotations concerning the events after the battle are found in QL, 42, 675–76. Marichal, Quart Livre, 181, n. 35, cautions that, in contrast to maps dating from after Rabelais's time, no map of Paris has been found from Rabelais's era or earlier that attests the rue pavée d'andouilles as the predecessor of the rue Séguier.