Epilogue

There is no vantage outside the actuality of relationships between cultures, between unequal imperial and nonimperial powers, between different Others, a vantage that might allow one the epistemological privilege of somehow judging, evaluating, and interpreting free of the encumbering interests, emotions, and engagements of the ongoing relationships themselves.

EDWARD SAID, "Representing the Colonized: Anthropology's Interlocutors," Critical Inquiry, Winter 1989

By the turn of the century, universal expositions had become a well-established tradition. But even as they occurred more frequently and spread to lands beyond Western Europe and North America, they began to have less of an impact on the public. Easier travel and more sophisticated communications made possible other ways of seeing and understanding foreign places, cultures, and societies. The original goal of representing the entire world in the microcosm of an exhibition grew obsolete. In the twentieth century specialized fairs focusing on industrial artifacts, arts and crafts, and colonial products became commonplace. With this shift the format of the fairs did not necessarily change; rather, many of the thematic and architectural experiments carried out at the universal expositions were adapted.

For example, the colonial exhibitions in France—first held in 1894 in Lyon, then in 1906 and 1922 in Marseille and in 1931 in Paris—duplicated many of the structures built on the Esplanade des Invalides in 1889. As Jean-Claude Vigato has argued, their architecture celebrated two aspects of colonial culture: the spectrum of exoticism (in the pavilions built according to the indigenous styles of territorial possessions) and the "civilizing mission" of expansionism (in the Western-style metropolitan palaces).[1] The exoticism is illustrated, for example, by one of the most memorable corners of the 1931 Colonial Exposition in the Bois de Vincennes in Paris: the Tunisian section. Designed by Victor Valensi, an architect who had studied Tunisian residential architecture, the complex had two components: the main pavilion, in a neo-Islamic style like that of the nineteenth-century national "palaces" at the fairs, and the market (the souk), reminiscent of the Rues du Caire and Rues d'Alger.

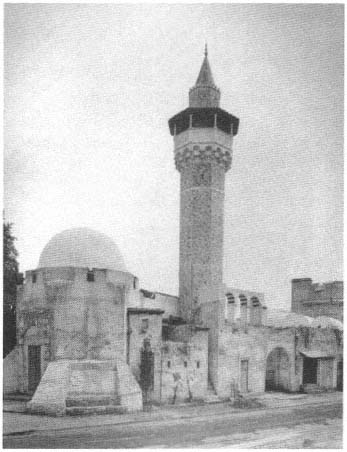

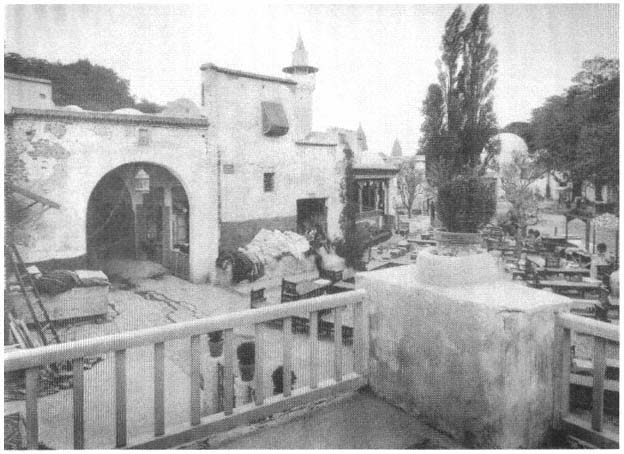

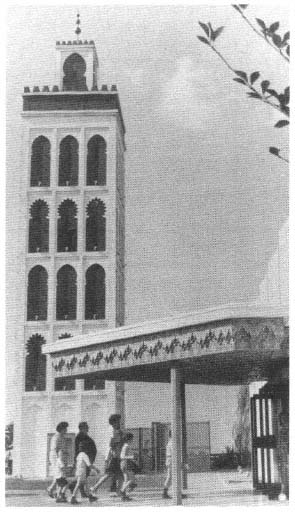

The Tunisian souk occupied a large area between two avenues abutted by buildings with irregular facades, creating an effect of incremental growth; a mausoleum and a minaret added "authenticity" (Figs. 117–118). The tortuous

Figure 117.

Tunisian quarter, Paris, 1931 (L'Exposition coloniale de Paris,

Paris, n.d.).

interior streets were covered either by vaults or by the roofs of the structures on two sides, and they were poorly paved. The organic effect was enhanced by the use of stones to patch up a brick structure and vice versa; plastering was irregular (parts of it seemed about to fall); and striking fragments from demolished buildings were inserted randomly into the structures. In the words of a contemporary critic, "the architect Victor Valensi forced himself to reconstitute something badly built, and he succeeded perfectly."[2]

The quarter was populated by three hundred Tunisians in "national costumes," preparing and selling foods, working in leather and copper, and sell-

Figure 118.

Tunisian quarter, entrance to the souks, Paris, 1931 ( L'Exposition coloniale de Paris, Paris, n.d.).

ing all kinds of local crafts, among them carpets. Music was played in a café, where "real" Tunisian girls performed the belly dance—still popular, as demonstrated by the crowds attracted. A snake charmer displayed his talents (and thus belonged to Burton Benedict's "curiosities" category; see chapter 1). The architecture of the quarter, the presence of the indigenous people, and the products displayed and marketed, as well as the noises, smells, music, and singing, created an "integral reconstitution of [Tunisian] souks."[3]

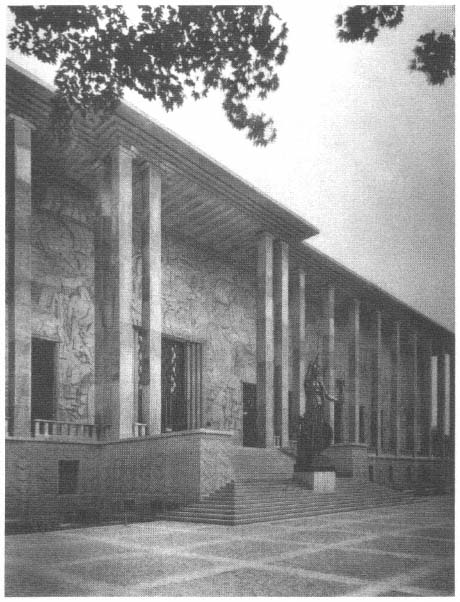

The "civilizing mission" of Western culture was celebrated at the same fair in the Museum of the Colonies, designed by Léon Jaussely and Albert Laprade in

Figure 119.

Museum of the Colonies Paris, 1931 ( L'Exposition coloniale de Paris, Paris, n.d.).

the "Greco-Latin tradition" (Fig. 119). Laprade argued that a colonial style would not flourish under the Parisian sky; besides, it would be impossible to select one of the many colonial regions to represent all of overseas France. Nevertheless, elements from various colonies appeared in the structure. For example, the surface decoration in the subbasement suggested "primitive civilizations," the ironwork borrowed motifs from Berber carpets, and the Ionic capitals of the colonnade were found in a simpler form in southern Morocco.[4] The museum was seen at the time as belonging to the esprit nouveau, with "a perfume of Islam and of very primitive civilizations."[5] In addition, Albert Janniot's bas-reliefs in the colonnade, depicting the colonies of France, literally conveyed a message about the nature of colonialism (Fig. 120). Colonies were shown as well-integrated parts of the French sociopolitical and economic mechanism. It was argued at the time that Janniot's depiction was like a "mirror of the world" and carried no militaristic overtones—that it was not "a triumphal ode, but the familiar and grand epic of human activity and of nature's fertility."[6]

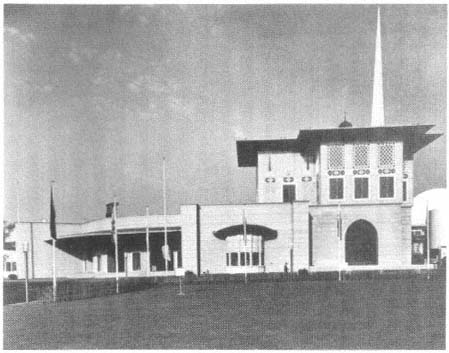

The pavilions of noncolonial Islamic nations in the twentieth-century expositions also carried over many traits from the preceding century. This is perhaps best illustrated in the structure Sedat Hakki Eldem designed for Turkey for the 1939 New York World's Fair (Fig. 121). The young Turkish republic, born out of the ashes of the Ottoman Empire, was represented in a complex that blended modernist and neo-Ottoman forms. For example, its main pavilion was derived from residential prototypes, reminiscent of the numerous Ottoman structures in nineteenth-century expositions and going back to the 1867 Pavilion du Bosphore. Its courtyard, with a fountain and brightly colored tiles, and its small reproduction of the covered bazaar in Istanbul reenacted other favorite themes. Meanwhile, the displays inside stressed the modernization of Turkey.[7] The tension between modernization and a historically defined cultural image thus continued.

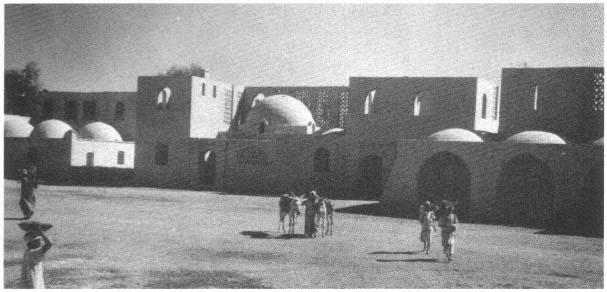

Such a pattern has been common in the architectural representations of Islam in more recent world's fairs that have recycled, for example, the familiar elements that signified North African Islamic architecture to the West for one hundred years. The Moroccan pavilion at the 1967 World Exhibition in Montreal was a square building with a sixty-five-foot minaret; its decoration—horseshoe and lobed arches, sculptured wooden ceiling, mosaic floor—drew on cultural

Figure 120.

Bas-relief depicting North Africa, Museum of the Colonies, Paris, 1931 (Charbonneaux, Les Bas reliefs du Musée des colonies ).

Figure 121.

Sedat Hakki Eldem. Turkish pavilion, New York, 1939 ( The New York World's Fair,

New York, 1977).

symbols that had long been part of the exposition repertoire (Fig. 122).[8] The Tunisian pavilion nearby was organized around a courtyard surrounded by arcades and vaulted areas, "recreating the authentic atmosphere of the souks . . . of Tunis"; under these vaults, weavers and coppersmiths practiced their crafts.[9]

The themes developed in representations of non-Western cultures at the universal expositions ultimately pervaded twentieth-century institutions and popular cultures. The following case studies give a broadbrush picture of the persistence of this nineteenth-century heritage and point to some new directions.

As an important cultural institution of our century, the Musée de l'Homme in Paris represents the French Left's impact on the reading of non-Western cultures in the 1930s. It was founded on a humanist universalism that reinterpreted anthropology and ethnography, but it pursued many themes from the nineteenth-century world's fairs. The Musée kid l'Homme (Museum of Man)

Figure 122.

Moroccan pavilion, Montreal, 1967 (General

Report on the 1967 World Exhibition, vol. 1).

goes back to the Musée Nationale d'Histoire Naturelle, established in 1793, which became the Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro in 1878 and remained in the Trocadéro Palace after the closing of the exhibition. With its emphasis on re-creating the atmosphere of foreign places, the Trocadéro museum was a permanent version of the non-Western displays at the world's fairs and did not reflect a clear rationale: it was neither an instructive exhibit—like those typical

of natural history museums—nor a display of beautiful objects—as in a typical museum of art in the nineteenth century.[10] It was filled randomly with curiosities, costumed mannequins, dioramas, and so forth.[11] In 1938 the museum was reorganized as the Musée de l'Homme by two anthropologists, Paul Rivet and Georges-Henri Rivière, in a new building designed by Jacques Carlu, Louis Boileau, and Léon Azama.[12]

Rivet and Rivière's undertaking had radical scientific and political goals, as they attempted to present societies in their entirety by contextualizing the products through ethnographic research and documentation. All races and cultures were on exhibit, and neighboring cultures were placed next to each other to allow comparative observation of different regions. According to Rivet, the goal was

to assemble in a general synthesis the results provided by specialists and to force them thus to compare their solutions, to check them with one another and secure for them mutual support. Humanity is an indivisible whole, in space and time.[13]

The modern West, however, was altogether absent from this picture of humanity. In James Clifford's words, "the orders of the West were everywhere present in the Musée de l'Homme, except on display. . . . The identity of the West and its 'humanism' was never exhibited or analyzed, never openly at issue." Here, Westerners could observe other cultures and societies, but their own exclusion from the display reiterated their position of power.[14]

Once again, as at the expositions, non-Western cultures were placed on stage, arranged according to European norms. The siting of the indigenous quarters at the expositions prefigured the organization of the Musée de l'Homme: societies believed to be similar were placed next to each other. And like the world's fairs, the museum conveyed a political message about power relations between societies. Despite the intentions of their progressive and humanist founders, the ethnographic museums in France engaged in propagandistic activities on behalf of colonialism in the 1930s (they have been described as "incomparable instruments of colonial propaganda")[15] because of their effectiveness in acquainting the public in the metropole with the benefits of French possessions abroad. Moreover, just as the Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro was an extension of the 1878 exposition, the Musée de l'Homme was conceived as a permanent part of the 1937 International Exhibition.

The parallels between the Islamic quarters of the universal expositions and some urban design experiments (in colonial and noncolonial settings) are also revealing. In chapter 5, I discussed the impact of the universal expositions on architectural theory and practice in Muslim countries in the late nineteenth century. The thread is longer and more tangled than the chapter suggests, however; it reaches to the present day and raises questions about the dialogue between cultures, in particular about the impact of colonial architecture on postcolonial efforts to express national cultures in pure and historically sound forms. As seen in this study, the expositions created settings where cultures were condensed into architectural summaries. The meaning of architectural representation differed in noncolonial and colonial contexts. In the noncolonial context, the search was for a cultural self-image that would underscore what was different about the represented nation and hence empower it as a distinct identity. In the colonial context, the subject and the object were no longer the same, and cultural characteristics of the represented culture were determined by the colonizing culture; the outcome was to empower the latter. Nevertheless, one type of representation influenced the other, and the end products displayed similar characteristics.

In the colonial context, neo-Islamicism in architecture had begun with the pavilions of North African colonies erected on the exposition sites. The appropriation of this style into large-scale buildings—from post offices to banks to theaters to townhalls—in the colonies formed the next stage, from 1900 on.[16] The third stage was marked by an interesting dialogue between indigenous architecture (in particular residential architecture) and early modernism. A number of studies by French architects in the 1920s and 1930s highlighted the spatial, picturesque, and architectonic qualities of vernacular architecture—among them Victor Valensi's L'Habitation tunisienne (1923), Augustin Bernard's Enquête sur l'habitation rurale des indigènes de la Tunisie (1924), Jean Galloti's Le jardin et la maison arabs au Maroc (1926) with sketches by Albert Laprade, and A. Mairat de la Motte-Capron's L'Architecture indigène nord-africaine (1932). This interest was connected to the resident general Louis Hubert Lyautey's romantic, if politically charged, notion of preserving the "poetry," the "originality," the "charm," and the "beauty" of the casbahs in Morocco and building modern French cities, villes nouvelles, adjacent to them in the 1910s and 1920s.[17] He described the Arab towns of North Africa passionately: "You are familiar with the nar-

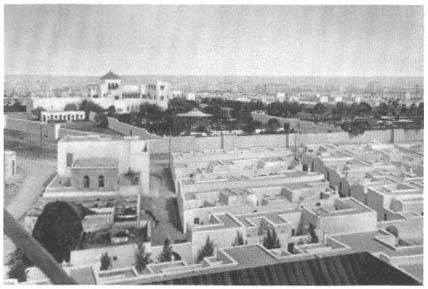

Figure 123.

Casablanca, Nouvelle Ville Indigène, aerial view (Vaillat,

Le Visage français du Maroc ).

row streets, the facades without opening behind which lies the whole of life, the terraces upon which the life of the family spreads out and which must therefore remain sheltered from indiscreet looks."[18]

The urban design policies of French planners for indigenous populations went beyond preservation and extended to the creation of new neighborhoods. Although in scale and ambition they may not have matched the new cities created for French settlers, experiment like the new madina of Casablanca made a significant impact, ultimately affecting the postcolonial searches for an expression of cultural identity in architecture and urban form. To accommodate the growing Moroccan population of Casablanca, Henri Prost, Lyautey's architect-in-chief, proposed a new quarter, separate and formally different from the settlements designed for the French. Albert Laprade, who had already undertaken a systematic study of the Moroccan vernacular, was chosen to design it. The project was then carried out by two of Laprade's associates, Albert Cadet and Edmond Brion, who took into consideration the "customs and scruples" of the indigenous populations as well as French "hygiene."[19]

Laprade's madina was based on Moroccan urban patterns, particularly the spatial contrast between the street and the interior courtyards of houses (Figs. 123–124). Reinterpreting local forms and decorative motifs, he created

Figure 124.

Casablanca, Nouvelle Ville Indigène,

street (Vaillat, Le Visage français

du Maroc ).

"sensible, vibrant walls, charged with poetry." Although these white walls defined cubical masses, their irregularity gave them a "human" touch. The project was more than a stylistic exercise; the architect's ambition was to integrate into his design "values of ambience" as well as a "whole way of life." Architecture for Laprade was "a living thing" and "should express a sentiment." The spatial and programmatic qualities of the project revealed the goals of the architect clearly: there were pedestrian streets and courtyard houses, markets, neighborhood ovens, public baths, mosques, and Quranic schools—all in neo-Moorish styles, "preserving everything respectable in the tradition," but constructed with modern technology and materials.[20]

This emphasis on local forms and their broader meanings is associated with Lyautey's thoughts on Arab culture as different from European culture but not inferior to it:

[T]here, the secret, it is the extended hand, and not the condescending hand, but the loyal handshake between man and man—in order to understand each other. . . . This race is not inferior, it is different. Let us learn how to understand their differences just like they will understand them from their own side.[21]

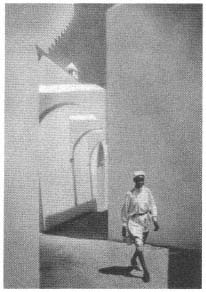

Figure 125.

Fathy, New Gourna, street (Fathy, Architecture for the Poor ).

Both Europeans and Arabs must understand that Arab culture is distinct from European culture. The architectural and urban forms that articulate this difference therefore must be continued. Benevolently paternalistic colonial administrators and architects assumed the responsibility to display Arab architecture to educate not only the French but also Arabs.

An attitude similar to Lyautey's characterizes the work of the distinguished Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy, whose well-known experimentation with the village of New Gourna goes back to the 1940s. Emphasizing the importance of tradition, Fathy reinterpreted the indigenous architecture of the Egyptian countryside, juxtaposing and reorganizing such key spaces as the square domed unit, the rectangular vaulted unit, the alcove covered with a half-dome, and the courtyard (Fig. 125). Arguing that the rural vernacular offered excellent examples of "light constructions, simple, with the clean line of the best modern houses," he relied on the power of volumes and masses and abstained from using color or texture on his walls.[22]

Fathy's insistence on returning to the oldest and purest building traditions of Egypt (those of the countryside) perhaps illustrates Frantz Fanon's analysis of the "passion with which native intellectuals defend the existence of their na-

tional culture,"[23] but it also grew out of French colonial architectural experiments in North Africa. Fathy's courtyards, private streets, and residential clusters; his aesthetics founded on simple volumes; his public building types (market, crafts khan, mosque, bath); and even his socially ambitious program had counterparts in Laprade's new madina. In New Gourna, Fathy attempted social reform by revitalizing the traditional way of life both in the built environment and in the patterns of production, which were founded on crafts and construction materials, namely making bricks. This approach was essentially like Laprade's idea of allowing for "a whole way of life" in the new madina.[24]

An even more striking parallel between Fathy and Laprade is their paternalism. Through such prominent spokesmen as Lyautey, French colonialists, as authorities on good taste and fine culture, argued they were reiterating the local culture and helping the Arab populations to understand and value their own heritage. Fathy's self-assigned mission was much the same: as peasants were increasingly coming to favor modern buildings, "an architect is in a unique position to revive the peasant's faith in his own culture. If as an authoritative critic, he shows what is admirable in local forms, and even goes as far as to use them himself, then the peasants at once begin to look on their own products with pride."[25] Therefore, the educated elite, represented by the architect in this instance, undertook to rejuvenate vernacular culture. Both parties feared losing "local culture" to "universal civilization." Whereas Fathy dreaded the universalizing effects of mass housing built by the Egyptian government and regretted the lack of a modern "indigenous style,"[26] Lyautey earlier had mourned the "hideous constructions" (built by French architects in classical styles) which were in the process of ruining the "charm and poetry" of Moroccan cities.[27] Yet each man's argument about built forms stemmed from different concerns and had different implications. For Fathy, a return to vernacular forms meant endowing modern Egypt with a cultural image, a manifest identity in the face of the universalizing power of Western technology. For the French colonists, the architecturally emphasized difference of North African Islamic cultures enhanced the power of France, not only because of the diversity of its possessions but also because of its tolerance.

The ironic discord between goals and forms echoes one of the main themes of the architectural representations of Islam in the nineteenth-century expositions. Whether designed by colonial powers or by independent states, the pa-

Figure 126.

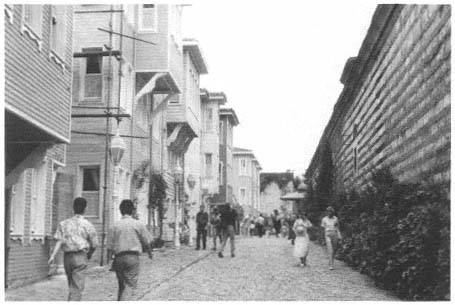

Sogukçesme Street. Istanbul (photograph by the author).

vilions had similar architectural characteristics, which evoked a general "Islamic style." One might well question, then, the notion that architecture can be manipulated to summarize cultures and nations visually; architectural representation is never pure and is always colored by power relations.

Recent urban preservation/restoration ventures also recall the Islamic streets of universal expositions. Although the importance of conserving the historical heritage cannot be denied, to reject the immediate past and the consequences of sociocultural and physical transformations leads to questionable results. The restoration of Sogukçesme Street in Istanbul offers a striking case study (Fig. 126). Located in the historical core between the north wall of Hagia Sophia and the outer walls of the Topkapi Palace, this street was lined with modest houses—some wooden, some concrete and brick—set against the walls of the palace. To accommodate tourism and emphasize the picturesqueness of the street, the entire built fabric was demolished, rebuilt in concrete frame-brick infill, clad in wood paneling, and painted in different colors—all to evoke the atmosphere of Ottoman Istanbul as described in European travel literature. Disguised to look like houses, the new buildings are actually hotels and pensions, complete with restaurants, cafés, and night clubs.

This major intervention, involving the displacement of the former residents, changed the character of the street dramatically from that of a neighborhood to that of a touristic strip. With its stage-set quality (there is also a crafts workshop nearby), the seemingly authentic residential fabric is a contemporary version of the Islamic quarters of expositions, now situated in a city with a powerful Muslim heritage. Ironically, its alienation from the rest of the urban fabric of late twentieth-century Istanbul makes it as much a curiosity in that city as the Rues du Caire and the Rues d'Alger were in nineteenth-century Paris.

The story has a counterpart in many European cities today, where non-Western quarters have become an integral part of the urban reality. The economic advantage of using cheap labor from abroad, from the less fortunate "peripheries" of the capitalist system, resulted in the immigration of large numbers of guest-workers to European cities. Whereas large waves of immigrants were attracted from former colonies to the metropoles (North Africans to France and Indians to Britain) and other immigrants from poorer to richer countries in Europe (Turks and Greeks to Germany), the pattern was not definitive, and a mosaic of different nationalities began to coexist in European environments. During the past three decades ethnically distinct neighborhoods have soared: for example, the Nineteenth Arrondissement of Paris is populated by North Africans, and Berlin's Kreuzberg quarter is now known as kleine Istanbul . Though their architectural forms and styles are European, these neighborhoods bring a cultural otherness to these cities with their signs, smells, noises, languages, and different urban use patterns.[28] They thus duplicate some of the carefully orchestrated elements of the non-Western quarters at the universal expositions, albeit to stay and to redefine European urban/cultural identity.

Today some symbols once valued for their exoticism can lead to political confrontation. For example, the "headscarf controversy," which produced heated debates on laicism in public education in France in the fall of 1989, began when two Tunisian female students in a Parisian technical high school wanted to keep their heads covered to comply with an Islamic code.[29] The debates that followed raised important questions about the presence of the Other in European culture as well as the "speaking back" of this Other. They suggest that in the future binary oppositions may no longer define cultures and cultural boundaries themselves may disintegrate.

Yet Eastern dress has always fascinated Westerners, who have appropriated it for festivals and celebrations, like the masked balls at the court of Louis XIV.[30]

Figure 127.

"Kadine aux mousselines"

(Dépêche Mode [1989], no. 24).

Twentieth-century haute couture sporadically recycles images from the "Orient." Paul Poiret in 1911 made a memorable debut in fashion design with his "Oriental" collection, presented at a Thousand and Second Night party. The setting included illuminated fountains, Persian rugs, Middle Eastern music, and even souks with "craftsmen at work"—all of it probably borrowed from the stages of the universal expositions. In Peter Wollen's words, "The whole party . . . [was] set in a phantasmagoric fabled east."[31] A more recent version of sumptuous "Oriental" festivity was Malcolm Forbes's seventieth birthday party in August 1989, celebrated in Tangiers, where belly dancers and Moroccan cavalry provided the entertainment in luxurious tents. The famous guests of the billionaire showed up in Eastern-style clothing.

These grand-scale events affect popular culture. While editorials in the French press pursue the implications of the "headscarf controversy," another sector broadcasts new "Oriental" designs using terms like odalisque, reiterating (and exploiting) the historical fascination with the "imaginary Orient." In these images fashion models hide their faces behind literal or implied veils and display the submissiveness expected of Muslim women (Figs. 127–128). The

Figure 128.

"Odalisque aux bijoux" (Dépêche Mode

[1989], no. 24).

phantasmagoric attraction of Islamic cultures today thus coexists with the problematic sociopolitical reality stemming from the European absorption of these cultures.

The patterns of cultural representation encountered in nineteenth-century universal expositions, then, maintain their authority at large but have also become more complex in response to new sociopolitical and economic power relations. Even as Western popular culture imbues Islam with dreamlike images, the very symbols that represent the culture are seen as threats. Islamic cultures, on the other hand, continue to display themselves according to images drawn through the eyes of others, with references that rely heavily on nineteenth-century legacies and that broadcast simultaneously old and new value systems. This complex and multilayered dialectic—within each culture and between cultures—may play the most important role in the rapidly changing cultural definitions of the late twentieth century.