Immortality

For further interpretation of the portraits, I turn now to a description of the pictorial décor of the three tombs built in the Southern Qi period. All the tombs were early broken into; this and ensuing damage from the elements left no tomb wholly intact. Initial reconstructions of décor were based on each tomb's surviving pictorial and inscribed bricks, which were then compared with the remains from the other two tombs.[73] What follows is a composite description of the three.

Although they differ somewhat in shape, all are single-chamber, barrel-vaulted tombs fronted by a narrow passageway. Except for basalt doors and frames, all are constructed of gray bricks, with the bricks of the surrounding walls arranged in layers, the typical three rows of horizontal bricks to one row of vertical bricks.

Pictorial decoration comprised both wall-paintings and pictures in brick-relief. The former, found in the passageways, appear to have been painted in red, white, and blue on a green ground. Unfortunately, the colors had for the most part peeled off or faded by the time of excavation, and only faint daubs were visible.

Relief bricks, however, enable us to tell more of the original ensemble. Many of the bricks in the burial chamber are embossed with designs such as blossoms, coins, or relief lines in checkerboard patterns, some of which bear traces of paint.[74] All the relief murals are constructed of two or more molded bricks. In the corridor, above the first pair of stone doors, are two discs, identified by inscription as "Little Sun" and "Little Moon" (presumably referring to the size of the mural). A three-footed crow with wings outspread stands inside the sun (fig. 36). In the moon can be seen a tree, identified in the report as a cassia, under which a hare stands on his two hind feet, his front paws holding a long pestle that rests inside a mortar (fig. 37).

On either wall of the corridor sits a single lion (77 × 113 cm) with lolling tongue and upswept tail (fig. 38). Traces of red paint remain on ears, eyes, nose, and tongue; cheeks are flecked with white. Showers of blossoms fall around him. Between the first and second doors of the corridor, on each wall, stands a guardian warrior (79 × 31 cm), wearing pleated trousers and a mailed doublet. He clasps a long sword that reaches from his waist to his feet.

As one enters the main chamber, a long mural (app. 2.40 × 0.94 m) is seen on each of the upper long walls (figs. 39 and 40).[75] The picture on the left (west) wall shows a man rushing forward. Turning from the waist, he gestures to a long tiger striding behind him. The picture

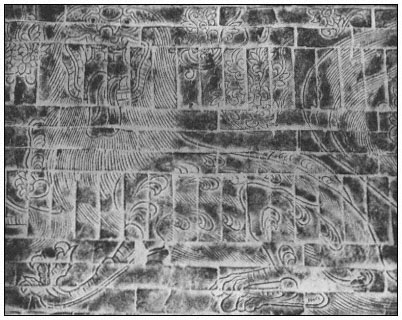

38.

Lion.

Rubbing of a brick relief mural, tomb at Jinjiacun, Danyang county,

Jiangsu province. Late fifth century A.D. Nanjing Museum.

(Photograph courtesy of James and Nicholas Cahill.)

on the right wall is similar: the animal, however, is a dragon. Inscribed bricks identify the images as "Great Dragon" (da long ) and "Great Tiger" (da hu ). The tall, slender men wear short tunics tied at the waist by ribbons that float behind them, while feathers sprout from their sleeves and tight trousers (figs. 41 and 42). They wave toward the animals fly whisks or sheaves of grasses. One holds out to his animal companion a small ladle from which flames emerge.[76] Cloudlike swirls that surround the images and accompany blossoms hanging in the air reinforce the sense of rapid motion conveyed by the prancing figures and floating garments.

Above each animal three small figures face the winged men (figs. 43–45). Their knees are bent, their long robes and scarves twist, ripple, and float behind them.[77] They, too, are accompanied by cloudlike swirls and floating blossoms. Each flying creature holds an object: a flaming tripod, musical instruments, a tray, clusters of what are,

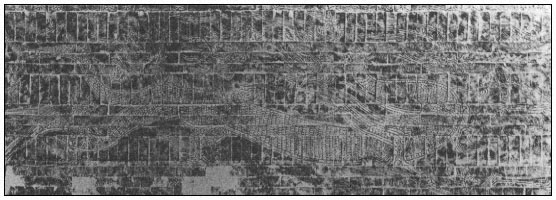

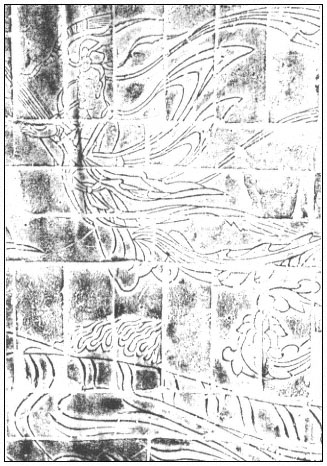

39.

Immortals with Dragon.

Rubbing of a brick relief mural, tomb at Wujiacun, Danyang county, Jiangsu province.

Late fifth century A.D. Nanjing Museum. (From Yao and Gu, Liuchao yishu. )

perhaps, jewels or fruits. Inscribed bricks found in the tombs identify them as celestials (tianren ).[78]

The portrait reliefs of the Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi, each figure separated by a single tree and accompanied by an inscribed brick, follow the murals of winged men and striding animals, and at the same level. Two of the images are now missing from the Wujia tomb; the order of the remaining forms and their division on the left and right walls are identical to those of the Jinjia tomb, as they are to the earlier, Nanjing relief. They are, moreover, almost the same size as the latter.[79] Traces of red paint remain on trees and musical instruments.

A few centimeters below these images, series of relief pictures, separated by bricks with floral designs, combine to form uniform murals, some 4.97 meters long, on both walls. Together the figures form a procession of foot soldiers and cavalry. The mailed horses are festooned with pennants and feathers; robed or trousered attendants bear standards or canopies; mounted musicians tootle pipes and bang drums. These are the honor guard, fit for an emperor (fig. 46).[80]

Thus, the Seven Worthies portraits, the only figure reliefs in the Nanjing tomb, have a new status. From the stone mythical animals that once lined the outer paths to the tombs, to the relief lions and

40.

Immortals with Tiger.

Rubbing of a brick relief mural, tomb at Wujiacun, Danyang county, Jiangsu province.

Late fifth century A.D. Nanjing Museum. (From Yao and Gu, Liuchao yishu. )

warriors that guard the corridors, to the appanages of attendants, cavalry, musicians, and so forth, the Worthies are now associated with royalty, wealth, and power.[81] The basis for their association lies not in their once-worldly rank, but in their symbolic status—like-minded persons to whom one is committed in friendship.

The other images in the tombs bespeak the concern for immortality, for which the tomb was, appropriately, the traditional site for its pictorial expression. None of these images is new. Countless tombs from the Han dynasty display moon-rabbits pounding the elixir of immortality, for example, or immortals (xian ), feathered creatures sporting with animals.[82] The authors of the archaeological reports identify the latter scenes as "Ascending to Heaven," speak matter-offactly of "herbs of immortality" (the sheaves of grasses, the clusters held by one of the celestials), and suggest that the flames of ladles and tripods might be melting cinnabar (important for compounding elixirs of immortality).[83]

Neither chimney sweeps nor emperors wish to come to dust, and it is only reasonable that imperial-tomb décor should reflect earnest hopes as well as the right of the deceased to preferment. For did not Shen Yue, in his History of the Song Dynasty, note that the three-footed crow appears when the one who rules shows compassion and filial devotion?[84] And did he not explain that when the ruler refrains from

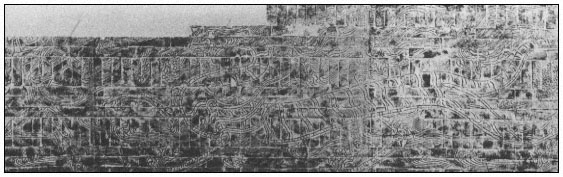

41.

Immortal with Tiger.

Detail of a brick relief mural from the Xiu'anling, Danyang county, Jiangsu province.

Late fifth century A.D. Nanjing Museum.

(Photograph courtesy ofJames and Nicholas Cahill.)

delegating power to false ministers, the sun and the moon shine their lights brightly?[85]

The beliefs and their pictorial expressions are traditional. The association of scenes of immortality with portraits of the Seven Worthies, however, is new. The latter, like the images of the imperial cortège, represent the terrestrial existence of the deceased (his like-minded

companions), as the immortality scenes reflect his hoped-for heavenly existence. As such, the Seven Worthies murals, for reasons now clear, replace the countless images of bowing officials and imperial emissaries who attested the worldly fame and virtue of the deceased in Han tombs—a simple but sophisticated substitution.

Their pictorial association with such imagery may well imply that the Seven Worthies had themselves achieved immortality. From our point of view, this seems only appropriate. To this day they occupy a prominent position in Far Eastern thought and art; metaphorically speaking, they are immortal. For the men of the fifth and sixth centuries, however, immortality was no metaphor, and a great deal of energy was expended on achieving the desired reality.[86] Admiring the Seven Worthies, identifying with them, or emulating them in literary production or life-style, was one thing. Ascribing to them a realized immortality was quite another and, it seems to me, an innovation. Granted that the pictorial systems of these tombs utilize conventional images, the patron's choices from the pool available to him must nevertheless bear significance, if only in the superficial sense that he finds the images pleasing rather than strange or shocking.

The question I pose, then, is why did imperial patrons find it pleasing to see the Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi, cultivated gentlemen and like-minded companions, in the company of immortals? The answer, I would speculate, lies in a fortunate accommodation of the Seven Worthies' ideal to the Daoist interests and beliefs of the Xiao family.

Six Dynasty developments in Daoist conviction and practice were to transform instituionalized Daoism forever.[87]A New Account of Tales of the World, so important an expression of values of certain of the fourth-century elite, makes no reference to the important instructions revealed by Perfected Immortals from the Heaven of Supreme Purity in a series of visions to an otherwise unknown Yang Xi. Nor does it mention their transcription—events that occurred at about the very time that Xie An, Sun Chuo, and Wang Xizhi were roaming the hills in convivial reclusion, debating Mysterious Learning, and admiring the landscape. Yet by the time of the accession of the first Southern Qi emperor, the esoteric texts of what was to become the Mao Shan sect loomed large in imperial interests. New realms of immortality, far higher and grander than those of the mere xian, had been revealed to Yang Xi, and it was not long before those who possessed its secrets attracted a following among the elite.[88]

There was no place in Mao Shan belief for the wonder-working

42.

Immortal with Dragon.

Details of figure 39. (From Yao and Gu, Liuchao yishu. )

43.

Celestials with Tiger.

Detail, rubbing of a brick relief mural from the Xiu'anling, Danyang county,

Jiangsu province. Late fifth century A.D. Nanjing Museum.

(Photograph courtesy of James and Nicholas Cahill.)

fangshi, or diviners, on whom earlier rulers—Cao Cao, for example—had relied, or for the superstitions of common folk.[89] For the Mao Shan sect, the highest levels of immortality, the Ranks of the Perfected, were reserved for the elect, sensitive and refined folk, capable of grasping spiritual subtleties.[90]

As Daoist beliefs changed, so did the style of its pictorial imagery, as both adapted to the values of the aristocracy. Missing from the Danyang scenes are the stocky or brutish immortals of so many Han depictions, replaced by slender, elegant creatures, whose graceful gestures authoritatively lure dragons and tigers, and by celestials, so light they soar. Their scarves and ribbons fly and twist in the wind, but they lose none of their unruffled composure. "How light and airy his graceful soaring," Zhi Dun had once remarked of Wang Meng.

44.

Celestial.

Detail of figure 39.

(From Yao and Gu, Liuchao yishu. )

Others had characterized Wang Xizhi as "now drifting like a floating cloud; now rearing up like a startled dragon."[91] Like celestials, the physical grace and elegance of men was a function of their inherent nature.

The Mao Shan texts were sacred, and so was their transmission. It was therefore crucial that the genuinely revealed manuscripts be weeded from the many forgeries in circulation by the late fifth century, and the Southern Qi rulers (like their Liu-Song predecessors) had a distinctly vested interest in encouraging the scholarly enterprise of collection, collation, and textual analysis that was required. For the texts, and their proper transmission, were the key to attaining the blessed state.[92]

The Ninth Patriarch of the Mao Shan sect is best known for his close relations with the first emperor of the Liang dynasty. But his work of Mao Shan scholarship and court proselytization began earlier, during the Southern Qi dynasty.[93] Poet, courtier, alchemist, and scholar, Tao Hongjing represented the new Daoist gentleman, at ease both at court and in reclusion. He received his first official appointment directly from the Qi emperor, Gao, and we learn from his

45.

Celestial.

Detail, rubbing of a brick relief mural, tomb at

Jinjiacun, Danyang county, Jiangsu province. Fifth century A.D.

(Photograph courtesy of Amy and Martin J. Powers.)

biography that he loved to play the qin and chess, that he was a skillful calligrapher.[94] Indeed, it was the elegant prose-style of the four thcentury revelations and the exquisite calligraphy of their transcription (as fine as Wang Xizhi's), we are told, that first attracted his attention to the manuscripts.[95] Although Tao Hongjing's intimations of immortality began in childhood, the ultimate lodging of his faith awaited, it would seem, an aesthetic stimulus.

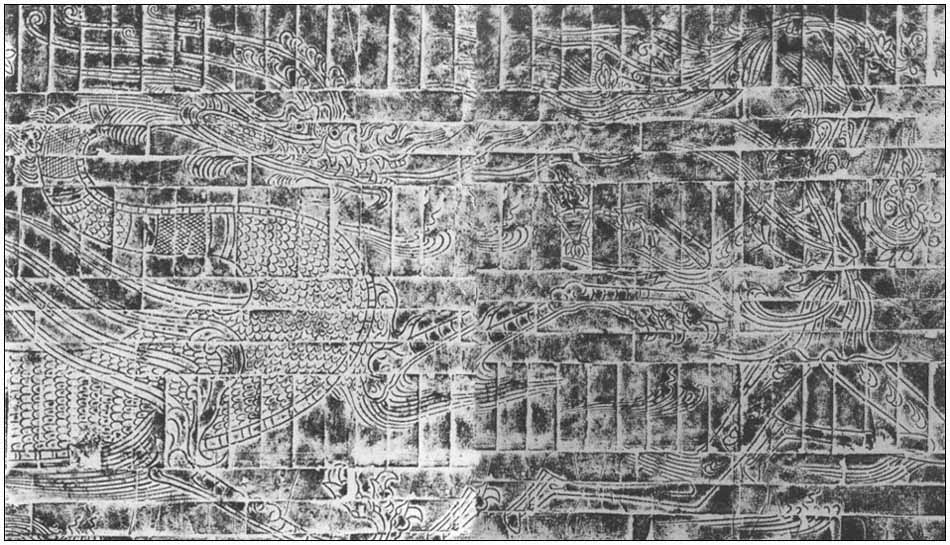

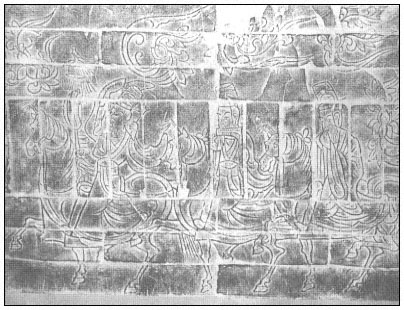

46.

Musicians on Horseback.

Detail, rubbing of a brick relief mural, west wall,

tomb at Jinjiacun, Danyang county, Jiangsu province. Fifth century A.D.

Nanjing Museum. (Photograph courtesy of James and Nicholas Cahill.)

The most distinctive feature of the sacred texts of the Heaven of Supreme Purity (Shangqing jing ), one that distinguishes them so remarkably from earlier texts of the Daoist Canon, is their literary quality.[96] The themes themselves—journeys through the Heavens, visits with nonterrestrials, celestial repasts—were not new, any more than they had been to Ruan Ji or Xi Kang. It is, rather, the poetic treatment, the style, that is new for such texts. Many aspects of this style can be traced to the literature of the early third century and specifically to the works of Xi Kang and Ruan Ji.[97]

It is here, where religion and literature join, that a new layer of significance accrues to the Seven Worthies portraits. For cultivated gentlemen concerned with the tenets of the new persuasion, familiar as they were with the old stories as well as with the literary output of our exemplars, there must have been a new resonance.[98] By this time the literature and philosophy of Wei-Jin were classics, studied by every educated man. Ruan Ji's famous prose-poem on the wanderings of the Great Man, or Xi Kang's concern with nourishing life, his

invitations to stroll hand in hand in the Supreme Purity or to ascend to the Purple Court—these were the very stuff of revelation.[99] The anecdotes of Ruan Ji's whistling, Xi Kang's forge, encounters with old men of the mountains—these random bits of tradition acquired a new emphasis, from the fifth-century point of view.[100] They signaled a search for the Way by these famous men and linked them with Daoist adepts. The recluse Zong Ce, for example, who yearned to roam in mountains and who repeatedly refused requests to serve the imperial family, painted a picture of Ruan Ji meeting the hermit of Sumen and sat facing it.[101] Tao Hongjing, in his redaction of a portion of the Mao Shan texts (the Zhengao ), included in his list of Daoist adepts Sun Deng, identifying him as the one Xi Kang met in the mountains. Sun Deng, added Tao, was also a whistler.[102] The Zhengao also referred to Xi Kang's Gaoshi zhuan and noted that Xi Kang had copied sacred texts.[103]

It is unlikely that Mao Shan adherents believed that the Seven Worthies, or any one of them, had already entered the ranks of The Perfected, the highest realm of immortality. Xi Kang, for example, when viewed from the new vantage as an adept who strove for purification, would have been understood as one whose execution—deliverance from the corpse by means of a military weapon (bingjie )—resulted only in imperfect purification.[104] As such, however, he could have become an immortal at a lower level, while attainment of the highest state lay before him, in the future. Nor were the seemingly wordly involvements of such as Shan Tao or Wang Rong a bar to attainment of the Way, for it was no longer necessary to withdraw to the mountains to achieve immortality. The aristocratic adept could be a recluse at court and withdraw into himself. In addition to more traditional means, the pursuit of immortality now also authorized the interior search (meditation and visualization). The heart/mind was as effective a terrain as the mountain. Wherever he was, the adept need only be sincere in his heart/mind, firm in his rectitude, and the Dao would come.[105]

Far from seeing contradictions in the wayward strands of the Seven Worthies' lives and traditions, the Mao Shan adept could weave them into a new mantle. Shan Tao and Wang Rong were really pure and unsullied by their worldly contacts. Xi Kang, even after corporeal death, continued his spiritual progression. If the new mantle of belief fit the Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi, it fit many who attended court funerals.

What they beheld in the arrangement of the murals was their own

future. The Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi are at the same level as the winged xian, who, in the Mao Shan hierarchy, have been reduced to lower-level immortals.[106] Above them, light as air, soar the celestials, visual hints of future glory. The portrait-mural itself—only men and trees, out of time and out of three-dimensional space; the slender (i.e., weightless) bodies and fluttering garments, so appropriate for those who have been roaming the heavens and have just now alighted for rest—is ideal for arousing and absorbing new associations. Unruffled, composed—how like the celestials they are! How like them are the celestials!

The very style of the forms, those thin, raised lines that contour only the essential, seems almost a deliberate choice. Indeed, it lacks the capability for conveying bulk: an artist cannot create the illusion of three-dimensional forms using only this technique. If a sense of weight—volume, solidity—had been pleasing to patrons, artists and craftsmen would have worked in a different style, as they so often did in the Han dynasty. We have only to look at the impressive modeling of the Eastern Jin relief bricks produced not far from Danyang to know that other styles were available if wanted.[107] Some of the floral reliefs in the Danyang tombs—for example, the embossed petals next to the xian —also convey a sense of bulk by their modeling.

That style has meaning is superbly exemplified by these portraits. For patrons who valued cultivated refinement and who yearned to soar, what other style could have been more appropriate?

Men of an earlier time characterized all the Seven Worthies as men of inner detachment, whose spontaneous but self-possessed behavior was the external sign of their inner purity. Later men, Shen Yue and Liu Xie for example, continued to see at least Ruan Ji and Xi Kang in that light, accepting even the others as like-minded companions. For Mao Shan adherents, also, it was the "inner detachment"—a purity for which the adept had to strive—that was the key to the Way.[108] It is not unreasonable to suggest that the Seven Worthies (and assuredly Rong Qiqi) had by this date achieved some measure of immortality in (enlightened) men's eyes.[109]

I doubt that members of the Qi imperial family arrived, like some Renaissance patrons, at the craftsmen's atelier with the Chinese counterpart of a neo-Platonic menu in hand. I do think, on the basis of what we know about the interests of the court, that patrons selected from the pool of workshop patterns images fraught with meaning, sacred and secular, for their lives. Indeed, with remarkable economy, three sets of images were linked in one chamber to arouse in those

who attended the funerals a host of multilayered associations, the full subtleties of which were likely to be grasped by only a select few. Even those of simple mind and small refinement, however, could not have failed to notice that emperors wished to be seen as worthy of admission to the Bamboo Grove, in this world and the next. It was for emperors that the Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi waited, dignified but relaxed, self-possessed—as only cultivated gentlemen can wait.

"The poetic value of the simple image lies in its power to evoke endless associations regarding the essential qualities of the object in question, despite its brevity in presentation."[110] As in lyric poetry, to which this aperçu refers, the use of "simple images" in the Seven Worthies composition was the key to its survival. Had the original composition been more detailed, its figures interacting or placed unambiguously in time and space, it would have lost that simplicity whereby it aroused a host of associations in viewers, especially those capable of tracing the waves to their source, to whom the composition could reveal even the dark and hidden.

For such a one the source was not only the events, the literary works, the many traditions of the Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi.[111] It was also a tradition of the Bamboo Grove, a tradition that became more abstract as, paradoxically, it grew in specificity of location and detail. No matter that none of the trees in any of the extant compositions resembled actual bamboo—it was by now a concept, not a reality.[112] The merest allusion to that concept, laden with the freight of history, interscribed with all that seemed most civilized, could reassure an emperor that no barbarian from the north could match him. It comforted men like Shen Yue in their darkest moments, yet, at the same time, aroused their highest expectations. It no longer even mattered, as I shall demonstrate in the next chapter, whose names were inscribed on the bricks. The composition was, quite simply, the Bamboo Grove. Everyone knew that.