| • | • | • |

Kaonde Kinship and the Matrilineal Core

Kaonde kinship terminology is based on the principle of matrilineal descent; a child belongs to the clan (within which marriage is forbidden) of his or her mother. According to Kaonde oral tradition, the Kaonde have always been matrilineal. The bishimi (folktales) I collected certainly presupposed a matrilineal system, and, judging from the colonial archives, the ideology of matriliny has been dominant at least from the earliest colonial period.[7] But whatever may have been the case in the past, in 1980s rural Chizela it was undoubtedly the matrilineal link that was seen as creating the most fundamental bonds between people, and as defining the basic statuses within the community of kin.

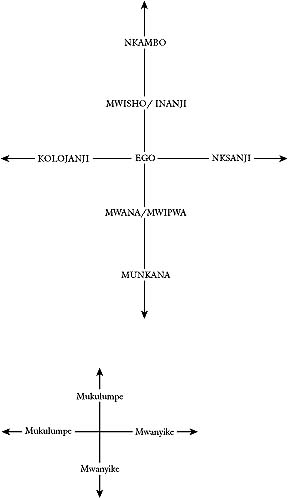

Within the Kaonde matrilineage there were eight basic kinship statuses; and for none of them are there simple one-to-one equivalents in English. In the following initial listing of the statuses I have given English equivalents simply because it is necessary to start somewhere, but the reader should bear in mind that these are grossly inaccurate. In the appendix I include a table that provides more accurate glosses as well as diagrammatic representations of the main kinship statuses, which may help to clarify the verbal definitions. The eight statuses were: inanji (mother), mwisho (mother's brother), kolojanji (older sibling), nkasanji (younger sibling), mwana (child), mwipwa (nephew or niece), nkambo (grandparent), munkana (grandchild). The basic shape of kinship classification within the matrilineage, and its gradients of power, are represented diagrammatically in figure 1.

Fig. 1 The matrilineal core

The first point to note is that all these kinship terms are classificatory, that is, they refer to a group of kin rather than a single individual. For instance, inanji (pl. bainanji) was a far more inclusive term than mother, being used for all of ego's female matrikin in the first ascending generation. In other words, inanji included not only ego's biological mother but all the latter's female siblings and her female matrilateral parallel cousins from the first to the nth degree.[8] If it were necessary to distinguish someone's biological “mother,” she was referred to as “the mother who bore X” (inanji wasema X). The point here is not that there was any confusion between biological and classificatory mothers, but that in terms of the bundle of moral obligations associated with the category inanji, these applied not simply to someone's biological mother but to all those categorized as inanji. The relationship between biological mother and child was certainly recognized as special, but its specialness lay in its intensity and strength; it was not seen as involving a different set of obligations from those of the general category inanji. Mwisho similarly referred to all the male members of ego's matrilineage in the first ascending generation, including all the male siblings and male matrilateral parallel cousins of all the women classified as ego's inanji.[9] In this matrilineal system, mwisho, not father, was the primary male authority figure.

The second point to note is that of the eight kinship terms only two, inanji and mwisho are gender specific. The two terms for sibling, kolojanji (pl. bakolojanji) and nkasanji (pl. bankasanji), specify whether a sibling is older or younger but not their gender. Kolojanji included all ego's older siblings who shared ego's biological mother, and all those matrilateral parallel cousins whose inanji was kolojanji to ego's inanji.[10] Similarly, nkasanji included all ego's younger biological siblings and all those matrilateral parallel cousins whose inanji was nkasanji to ego's inanji.[11] Because neither kolojanji nor nkasanji are sex specific, if a speaker wanted to indicate the sex, a qualifying adjective was added: kolojanji wamulume (male older sibling), nkasanji wamukazhi (female younger sibling). Normally this was only done if the context demanded it, just as English speakers refer simply to brothers and sisters without feeling it necessary to specify whether they are older or younger.

In the first descending generation ego's matrikin were different depending on whether ego was male or female. The same term, mwana (pl. bana), was used to refer to ego's biological children, all the biological children of a male ego's male bakolojanji and bankasanji, and of a female ego's female bakolojanji and bankasanji, were also termed ego's bana. But whereas a woman's bana were her matrikin, a man's were not. A man's biological children belonged to the matrilineage of their inanji. According to Kaonde kinship terminology, therefore, strictly speaking a man's children were not his kin (balongo). For instance, once when I was talking to Ubaya, the vice-chairman of the Bukama Farm Settlement about the rules of the scheme I asked about inheritance and whether plots could only be inherited by kin (balongo). Ubaya replied, “Ee, ne bana” (Yes, and also children). In other words, in the context of a discussion of male inheritance (the assumption was that, unless specified otherwise, the “farmers” of Bukama were male), a man's children would not automatically be thought of as his kin. A man's immediate heirs were his bepwa (sing. mwipwa). Bepwa were the children of a man's “sisters” (banyenga), the children, that is, of all his female bakolojanji and bankasanji; the bepwa to whom he was mwisho. The relationship between mwisho and mwipwa was a key authority relationship in local political life. The corresponding relationship between a woman and her brothers' children of course fell outside the matrilineage and seemed to have little significance for people.

In the second ascending generation there was just one term, nkambo (pl. bankambo), which was used for both men and women and included all those who were inanji or mwisho to ego's inanji or mwisho.[12]Nkambo was also used for a whole range of kin in the second ascending generation who, although not ego's matrikin, were linked to ego through affinal ties. The second descending generation also had one all-inclusive term, munkana (pl. bankana), which was used for all children of both sexes, of both ego's bana and bepwa, and could be loosely translated as “grandchild.” Only the bana of a female ego's female bana, however, were also members of ego's matrilineage, unless, that is, there had been a marriage of cross-cousins.

The basic set of matrilineal relationships stretched a net over the matrilineal clan linking each clan member to every other. Whenever two clan members met they would slot each other into an appropriate relationship, mwisho/mwipwa, inanji/mwana, kolojanji/nkasanji, and so on. Often people would not know their exact genealogical relationship, but the fact that they shared the same clan meant, by definition, that a genealogical relationship could be assumed. Kinship categories could be very flexible, as they are often for English speakers. For instance, the term aunt may be used to refer to the sisters of parents, the wives of uncles, and even women who are merely friends of the family, without there being any confusion in peoples' minds about the different relationships involved. Similarly, kinship terms in Kibala and Bukama had both a precise core of meaning and a far more diffuse and unbounded range of meanings, where the kinship term was being used more as a metaphor or analogy, indicating the kinds of expectations and obligations associated with a specific relationship. For example, when a young and an old villager met who did not know each other, they might well address each other as nkambo and munkana, indicating by this no more than that this was the kind of relationship in which they stood to each other.

As with any exogamous system, the Kaonde matrilineal clan depended for its reproduction on the “strangers” who married into it. Later I shall have more to say about the kind of structural tensions this involved both within and between households, and some of the ways in which they manifested themselves. Here I just want to describe the basic shape of the Kaonde household as a political and an economic unit. But first let me clarify how I am using this slippery term household.

Household is a term that at first sight seems to refer to an obvious and undeniable reality and yet, once one begins to think about what it actually describes in different contexts, is also a vague and shifting creature forever changing its shape. The assumption that the household can be treated as any kind of “natural,” unproblematic category, or that it can be taken to be a single decision-making entity, has increasingly come under attack, particularly by feminists.[13] On the one hand, it seems difficult to deny that in some sense all societies have households in that there is some kind (or kinds) of basic unit within which people live. On the other hand, the kind of units households are and what they do can vary enormously. Are they units of consumption and/or production? Are they units of reproduction and/or the sites where the socialization and education of children take place? What is their role in the political domain? None of the answers to these questions can be assumed. There are no universals, only specific answers for specific contexts; the household is an empirical rather than an analytical category.

One characteristic that is general, however, is that households are always both collective entities and made up of separate individuals. They are sites within which conflictual and supportive relationships are always entwined; disentangling the specific relations of subordination and domination that exist within this dense, and emotionally saturated, knot is not straightforward. It is important neither to romanticize the household—assuming that it can be treated as a single entity with a single set of interests, aims, and within which resources are unproblematically shared—nor, in reaction to such romanticization, to move so far in the other direction as to see households as no more than sites of an unrelenting struggle between warring autonomous individuals. In other words, the notion of the household has to be problematized. We have to start from its double-sided and sometimes contradictory character as an entity that both has common interests and aims and is made up of individuals with different interests and aims. What this means in any given instance can only be discovered through empirical investigation. So, to come back to the specifics of rural Chizela: How did the people of Kibala and Bukama themselves describe the basic units they saw themselves as living within?

The term household can be translated into Kaonde as ba munzubo (those belonging to the house), and household head as mwina nzubo (“owner” of the house). The name of the mwina nzubo implicitly included within itself all those belonging to that household; he (as in English, the presumption was that households were male-headed unless they were specifically defined as female-headed) was the embodiment of the household as a political entity. It was the male household head who constituted the basic unit within the political pyramid of kinship.

As economic rather than political entities, households were more units of consumption than production (the organization of production is discussed in the next chapter). In practice discovering the household to which someone belonged involved asking by whom was he or she “fed” (kujisha). A person might then be described as either being fed by X (bejisha), or as feeding themselves (mwine wijisha), depending on whether or not they were considered to be part of X's household, or to have their own household. Nonetheless, it was not always true that households were units of consumption in any literal sense. “Feeding” here could be used figuratively in the sense of “being responsible for.” Another important characteristic was that the cash incomes of husbands and wives, whatever their source, were not pooled to form a single joint household purse. Each spouse was seen as controlling the distribution of the produce of their own labor and their own income, even if this produce and this income was also seen as subject to a wide range of claims on the part of their spouse and other kin.

Most households in Kibala and Bukama consisted of a married couple and their dependent children, or a single adult. Female-headed households were fairly common in Kibala (12 percent of all households, see table 1) and very common in Bukama (35 percent of all households). The prevalence of female-headed households in Bukama was due, as I explained in the introduction, to its particular history. Female-headed households by definition had no adult male, and it was usual for a brother, an uncle, or some other male kinsman to act for husbandless women in the sphere of public politics. Although many men might have aspired to polygyny, only a small minority had two wives, and no more than a handful had more than two. In any formal political context a man and his wife or wives would constitute a single household, although in terms of their day-to-day economic organization spouses tended to constitute relatively autonomous units, each engaging in his or her own productive activities. This autonomy was especially marked in the case of polygynous men, with each wife having her own fields, her own granaries, her own kitchen, and so on. Normally a household never contained more than one adult male. Virtually the only exceptions were cases where one man was considered either mentally or physically incompetent.

| Kibala | Bukama | |

| Polygynous households | ||

| Two wives | 14 | 3 |

| Three wives | 1 | 1 |

| Polygynous households as % of male-headed households | 7% | 9.6% |

| Total male-headed households | 206 (88%) | 52 (65%) |

| Female-headed households | 29 (12%) | 28 (35%) |

| Total households | 235 | 80 |

Note: These figures are based on surveys I carried out in 1988. In Kibala my survey of household composition was based on 28 of the 31 settlements.

The next level in the political hierarchy above that of the household was that of the muzhi (village). Each muzhi was seen as consisting primarily of a core of matrilineally related households; and each had a headman (mwina muzhi, lit. “ “owner” of the village”), who was normally the most genealogically senior of the muzhi's male matrikin. The name of a muzhi referred both to a particular matrilineal segment and to its headman. The relationship between headman and household heads was analogous to that between a male household head and his dependents. In both there was the acknowledgment of a generalized authority that was also diffuse and nonspecific. The muzhi was in fact the household writ large, with the headman, as it were, standing for all those belonging to it (the bena muzhi), for whom he was able, and indeed expected, to speak.

Muzhi was first and foremost a political category that referred to a social rather than a geographical location; its primary meaning was a particular group of matrikin, not a physical settlement. Nonetheless, at any given time each muzhi was also associated with an actual geographical site. If someone said, “I am going to X,” mentioning the name of a village, everyone would understand that he or she was going to that particular place. The inhabitants of this physical embodiment of the muzhi would normally include, in addition to the headman and his matrikin, a number of people who had married into the village or chosen to live there for some other reason. Within this kinship-ordered political universe, however, these outsider individuals were excluded from the muzhi's own political hierarchy. “Belonging” to a particular muzhi had a number of different meanings. Individuals had a specially deep tie to the village of their birth mother (inanji wamusema); this was their primary village. However, they also belonged to some extent to the villages of other of their matrikin, and even though they did not belong to their father's kin group, in some weaker sense they also had ties there. For anyone in Chizela the wide range of meanings muzhi could have, and its shifting reference to people and places, did not create any problem, since the context would define which meaning was appropriate. For the Western reader, however, it is important to stress that the community constituting a village did not all live in one place and that individuals might be members in some sense or another of many different villages.

The way new villages, in the sense of physical settlements, came into being was normally through a particular group of kin within an existing village splitting off and forming their own autonomous settlement with its own headman. When this happened the old and the new villages would see themselves as linked by the same kinship ties as existed between their respective headmen, uncle (mwisho) and nephew (mwipwa), or older (kolojanji) and younger sibling (nkasanji), for instance. This particular relationship would then be frozen, defining the relationship between the two villages in perpetuity. Within a locality such as Kibala, most of the villages were linked in this fashion in a net of hierarchical relations. On becoming a headman, a man would take the name of his village and subsequently he would always be called by this name; a crucial part of what he was succeeding to, in fact, was a particular location within the kinship hierarchy. In other words, in inheriting the name of his predecessor a headman by definition also inherited all his predecessor's kinship relationships to other villages. Succession to headmanship was in principle adelphic, with the most senior male of the muzhi (in the sense of kin cluster) becoming the new headman on the death of the old. In practice, however, in the 1980s genealogical seniority in itself did not decide who would succeed but rather provided a field of candidates, all of whom were male matrikin of the late headman; and judging by the colonial records this seems to have been true since at least the early colonial period. Which of this field of candidates actually succeeded was decided by the senior members of the matrilineage (women as well as men) on the basis of individual candidates' competence. Interestingly, it seemed to be agreed that there should be a lengthy period, often one or two years, before a new headman was formally chosen. One way of looking at this time lag is as a space within which de facto power struggles had a chance to work themselves out. In other words, only when it had become clear who of the potential successors actually commanded the greatest support would the formal process of selection take place. Very occasionally, it seemed, a woman (usually the widow of a headman) might be recognized as a village “headman” in her own right. There was one such woman in Kibala, but this seemed to be more the recognition of a de facto situation than a genuine succession. Really, people told me, this woman and those living with her were part of another, male-headed, village; it was only because of quarrels between her and her male matrikin that she lived in a separate settlement.

Above the headmen were the chiefs (bamfumu). Each muzhi was seen as owing allegiance to a particular chief and in the vicinity of Kibala and Bukama this was Chief Chizela. In talking about the various settlements in Kibala people would distinguish between those that were “proper” villages (muzhi mwine), and those that were actually part of another village even though they were living in a distinct and separate settlement. In the 1980s a muzhi mwine was a village where the headman had been installed with the “proper” ceremony and that was recognized as a distinct villageby the local chief. The authority of a chief over “his” villages was, on the one hand, defined in the same all-encompassing way as that of the household head over his dependents and the headman over the members of his village; on the other hand, it was also vague and generalized. This was an authority seemingly accepted unquestioningly in principle but in practice virtually unenforceable—a reality recognized by the chiefs, who sensibly made no attempt to control the day-to-day lives of their ostensible subjects.

Having provided this overview of the building blocks of the kinship hierarchy, we are now ready to move on to look in more detail at the idea of social order embodied in this hierarchy and at its discourse on legitimate authority—in other words, at how it named the basic contours of power of the social landscape.