Chapter 8

Détente

Debating America in the 1960s

In the 1960s the American social model continued to excite a lively, and mostly acerbic, response among the French, especially the intelligentsia. These expressions of anti-Americanism, unlike those set off by troubles in the Western alliance or by foreign investment, were not for the most part generated by the Gaullist government. Yet the domestic debate about America moved the nation toward détente, as did the outcome of de Gaulle's efforts to end Washington's hegemony and curb the import of dollars.

Anti-Americanism attained a virulence in the mid-1960s that had not been seen since the early years of the Cold War. It was fueled not only by persistent French anxieties about the American way but also, to a lesser extent, by de Gaulle's attacks on the foreign policy of the United States and by student radicalism that erupted in massive civil disturbances of May–June 1968. Intentionally or not, Gaullism sanctioned anti-Americanism, and the student revolt targeted America's "imperialist" war in Vietnam as it intensified discussion about consumer society. Despite such assaults, anti-Americanism receded and the controversy over the American way abated.

The debate in the 1960s about the American socioeconomic model was far more diffuse than it had been during the previous decade. While America still represented consumer society, discussion of la société de consommation itself began to formulate the issue as "consumer society" and also as "industrial" or "postindustrial" or "technological" society, even as a "technocracy." Each of these terms suggested different aspects

of social modernity. Thus the debate extended its scope and introduced issues such as the technological imperative, rule by technocrats, environmental concerns, or the limits of the earth's resources. America became less the perpetrator of some universal crime and more a fellow victim of a global dynamic.[1] The American model was usually close at hand when the intelligentsia addressed these subjects, but America was no longer central to the discussion. Critics were less eager to single out the United States and blame the contemporary malaise on American greed or on Yankee-style buccaneering capitalism. For the historian this diffusion makes the debate harder to follow. But it represents a de-escalation of the controversy.

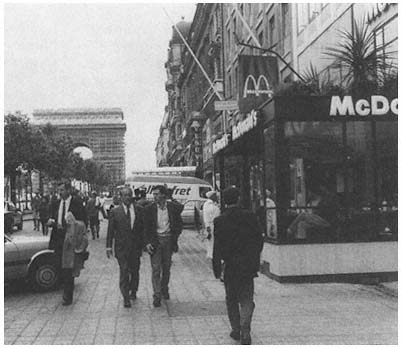

The debate not only became more cosmopolitan, it also became more French. Those who reflected on this problem were no longer speculating, as they had been as recently as the early 1950s, about an Americanized future. France was in the throes of Americanization (see fig. 20). The benefits as well as the costs of affluence were apparent. The French now enjoyed more comforts, easier communication and mobility, greater leisure and prosperity; but they also experienced a life-style centered on acts of purchase, instant obsolescence, incessant advertising, a profusion of foreign companies and products, congested cities, empty villages, a faster pace of life, pollution, and the corruption of language. The discussion was now less about America and more about what was happening to France.

If the debate evolved because the consumer revolution had arrived in France, it changed also because the reputations of the superpowers crisscrossed. America of the 1960s was different. Compared to the 1950s, the United States seemed simultaneously more imposing and yet more vulnerable. On the one hand, American power and presence were expanding on a global scale. If the American military vacated French territory in 1967, everywhere else American power seemed in the ascendancy. And the Western superpower was willing to use or threaten force in regions like Central America, the Caribbean, and, above all, Vietnam. One American senator could now speak of "the arrogance of power." American investments and popular culture accompanied the new global reach. On the other hand, American society was under attack from within. It appeared to be experiencing its own revolution marked by an upsurge in political radicalism, an emerging youthful counterculture, racial violence, and civil disorder associated with the war in Vietnam. The complacency of the 1950s vanished before a new mood of self-criticism. French observers of the American scene studied this

20. Americanization arrives: McDonald's on the Champs-Champs-Elysées.

(Courtesy François Lediascorn/New York Times Pictures)

"American revolution" and read the analyses of John Kenneth Galbraith, David Riesman, C. Wright Mills, Vance Packard, and Michael Harrington (all of which were now available in translation) as well as the criticism emanating from leaders of the new counterculture such as Herbert Marcuse and Jack Kerouac. President Johnson's Great Society called attention to the existence of poverty. Soviet scientific successes called into question rise eminence of American science, if not the entire educational system. America was a troubled giant.

As the United States became less dangerous, the Soviet Union became more so. For the left, in particular, the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia damaged confidence in the progressive nature of the Soviet model.

The debate about America in the 1960s, finally, differed from that of the early Cold War years because there were new names and a different balance among the disputants. There were some familiar faces such as Raymond Aron, Jean-Marie Domenach, and Maurice Duverger, but most of the protagonists were new. André Siegfried had died; Jean-Paul

Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, except for their indictment of American policy in Vietnam, were silent. The Communists were quiescent. There were fewer literary mandarins and more social scientists, and the tone was less hysterical and less personal. There was still plenty of politics and passion, but on the whole assessments were more shaded and restrained. And Gallic commentary on America seemed more balanced when the advocacy of the Americanizers became at least as ardent as the argument of the critics.

This final encounter between America and France focuses on how the intelligentsia viewed American consumer society. As in a parallel chapter on the 1950s, I concentrate on the popularizers, that is, the major intellectuals, and on books, reviews, and strategic newspapers like Le Monde that interpreted America for the French in the 1960s. However, in this encounter intellectuals share the rostrum with public officials and business managers.

If anything, the intelligentsia's vilification of consumer society escalated while America receded as the target of this scorn. It would be impossible here to explore the views of all those who attacked the new abundance, but such an analysis would include individuals like Jean Baudrillard, Bertrand de Jouvenel, Alain Touraine, Georges Elgozy, and Henri Lefebvre as well as literary and philosophical schools like that of the nouveau roman and structuralism.[2] These observers predicted that abundance would heighten alienation. They decried the valuation of objects over social intercourse, of personal gratification over the work ethic, and of prefabricated desires over real needs; they demonstrated how the act of purchase became an acquisition of social signs. Baudrillard spoke of consumerism as a pact with the devil in which individuals sacrificed their identity and transcendence for a world of signs. For these critics America became a reference point. The New World was often evoked as an example of this universal phenomenon but was now only rarely accused of being its progenitor. France had become like America. Thus France, it was said, had been victimized by advertising or become a giant suburb—just like America. Or consumerism had coopted the French working class, as it had American labor. Or it had "proletarianized" the youth of both societies. As one observer noted, given the French fetishization of the automobile, the slogan, "What's good for General Motors is good for the United States," now also applied in France.[3]

The issue of consumer society formed part of the radical student agenda in the 1960s. The so-called student revolution of May–June 1968 brought student occupation of the Sorbonne, generated a massive strike movement among the working class, paralyzed Paris, aroused widespread interest and comment, and momentarily frightened de Gaulle himself. Anti-imperialism, in this case opposing the intensified American military engagement in Vietnam as well as glorifying revolution in Third-World countries, was a major feature of the students' ideological discourse. But Americanization or consumer society were not the principal targets of the protesters of 1968. A general sense of disenchantment with the society of abundance informed the most radical members of the student movement, who had learned about this social evil from such leftist critics as Henri Lefebvre and Guy Debord. But the striking workers apparently wanted to participate more fully in the new abundance before they rejected it. And only a tiny fraction of the rebellious youth saw consumerism as an issue. One survey taken after the end of the spring disorders inquired into motives. With respect to la société de consommation, only 7 percent of those polled classified it as an issue of first importance while 80 percent relegated it to the status of a minor issue.[4] Topics like university reform and a general libertarian challenge to established authority—be it academic, administrative, political, or social—were more central to these dissenters.

Consumerism, like America, was a marginal issue in the social upheaval of the spring of 1968. After all it was the young, rather than adults, who had most quickly absorbed much of the new consumer culture imported from America. In 1961 when a bomb planted by the Organisation de l'armée secrète (OAS), the diehard secret military advocates of a French Algeria, wrecked a popular commercial establishment on the Right Bank called le Drugstore, an "enormous crowd of young Parisians gathered to mourn," according to Janet Flanner.

The Drugstore had been the most vital center of Americanization for them, for it was a complete replica of what an American drugstore is and means in the American way of life, and had more influence on Paris youth than any American book translated into French, or any Hollywood film ever shown here.[5]

Some might disagree both on how truly American le Drugstore was—in many ways it was a chic Parisian boutique—and with Flanner's estimate of its influence. But the reaction to its bombing does suggest the new prestige of American consumerism—at least to some Parisian youth. For the adolescents of the 1960s were the first generation to have

grown up in prosperity. They simultaneously absorbed and rejected consumer culture. They were, in the catch phrase of the time, "the children of Marx and Coca-Cola."

This discussion centers on the American way rather than on philosophical discussions about consumer society. Such reflections would lead away from my inquiry because consumer society during the 1960s, unlike during the 1950s, was increasingly treated as a phenomenon apart from America.

As a people Americans were, as in the past, liked. They were praised for their efficiency, dynamism, youthfulness, and generosity, even if they were also supposedly tyrannized by advertising and materialism, plagued with broken households, drugs, violence, and racism.[6] Nevertheless, the French, at least according to a poll of April 1968, saw themselves as resembling other Western Europeans far more than they did the Americans.[7] As a social stereotype, America as a gadget civilization—materialistic, conformist, optimistic, and soulless—persisted.

Such an interpretation appeared in Alain Bosquet's Les Américains sont-ils adultes? whose very title evokes the caricature of Americans as les grands enfants .[8] Bosquet, a novelist and poet, created an imaginary couple, the Browns, who lived in suburban Chicago, to portray Americans as slaves of material ambition. The Browns were eager consumers who defined themselves by their possessions and who purchased what everyone else owned. Suzy Brown was loyal to her brands—Kelloggs, Colgate, Avon—and learned about life by reading selections from the Book-of-the-Month Club. The Browns stayed at Holiday Inns and ate at Howard Johnson's so that their vacations held no surprises. This suburban couple had no passions. Even their God was, like them, "affable and boring," according to Bosquet. They strove to please everyone and avoided introspective or philosophical conversation. The Browns had no interest in such discussions because America itself was a dream; it was an ideal. This innocent idealism led the French novelist to conclude that Americans might be ahead of Europeans in a material and technological sense, but that intellectually or emotionally they were not adults.

A common lesson drawn from this stereotype was that America continued to be a cultural menace. For the French on both left and right, this persistent fear formed the exception to the growing détente. If other reservations about America faded, culture and civilisation remained at risk. On the left, for example, Maurice Duverger, the eminent political

analyst for Le Monde, published an interview in 1964 dissociating himself from what he called the currently fashionable idiotic anti-Americans, yet declaring:

It must be said, it must be written. There is only one immediate danger for Europe, and that is American civilization. There will be no Stalinism or communism in France. They are scarecrows that frighten only sparrows now. . . . Today, all that belongs to the past. On the other hand, the pressure of American society, the domination of the American economy, the invasion of the American mentality—all that is very dangerous.[9]

He compared American drivers on a busy Sunday to insects isolated in the shells of their cars moving together in close rank without touching. Once again we hear echoes of Duhamel's America the Menace . Duverger declared that in American society the basis of values was "money and gadgets." Contrast that, he said, to the situation in a country like France:

The employee who reads your gas meter possesses a scale of aristocratic values. He can distinguish perfectly among a nouveau riche, an intelligent man, and a poet. Whether he knows it or not, the cultural ensemble that: is at the core of his attitudes is shaped by a completely different historical legacy. I think this element will help us resist pressure from America.

Duverger concluded that Europe's problem was to reach affluence without passing through the "transitory phase of Americanization."

On the right, in the eyes of many French traditionalists, Americanization also signaled the degradation of culture. This reaction only reiterated what had been voiced as far back as the 1920s, if not earlier. In the 1960s Gaullism, and not only because of its anti-American foreign policy, inspired some of this conservative counterattack. De Gaulle, for example, appointed André Malraux as his first minister of culture. Malraux, who had once declared that America was a country without culture, busily promoted a traditional conception of high culture. It is not surprising that this atmosphere nurtured polemics against American cultural colonization.

The most discussed tract of this genre was René Etiemble's Parlez-vous franglais? Etiemble, a professor of comparative literature at the Sorbonne and former fellow traveler who had studied in the United States, warned his countrymen that they were being subtly colonized by the creation of a synthetic tongue that he dubbed franglais. Words, syntax, grammar, and even meaning were being corrupted by American exports. As an example of this barbarism Etiemble cited the report of a journalist written during the Algerian war:

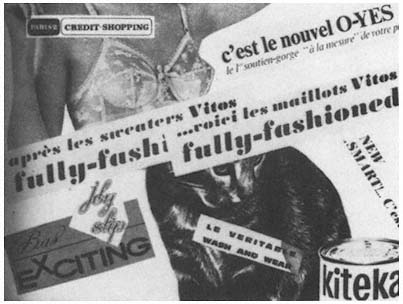

21. Ads in franglais. (Courtesy John Ardagh)

J'étais au snack-bar! Je venais de prendre au self-service, un bel ice cream; la musique d'un juke-box m'endormait quand un flash de radio annonça qu'un clash risquait d'éclater à Alger. Je sortis, repris ma voiture au parking et ouvris mon transistor. Le premier ministre venait de réunir son brain-trust.[10]

The perpetrators of this linguistic bastardization were numerous. They included NATO, scientists, doctors, journalists, advertisers and retailers, magazines like Elle, sports, television, and restaurateurs. But significantly not the intelligentsia. Servile merchandisers abused the French tongue to be stylish—"It's new, it's different." Noting how prepositions and articles disappeared in slogans like "Buvez Coca-Cola," Etiemble commented, "Soon, the partitive will disappear from French so that Coca-Cola earns lots of money in France" (239). Once the French language was a precise tool of analysis, but now it was becoming a synthetic tongue fit only for suggesting immediate sensations. The phrase becomes a word, the word an object—obviously the better to sell the object (see fig. 21).

For this academic the issue was far more than linguistic purity. Parlez-vous franglais? was patently a Gaullist polemic.[11] NATO publications, for example, urged European officers to speak American so that

they would come to think like Yankees. For Etiemble linguistic chauvinism was a means of cultural defense against America: "As long as the French still speak French and think like Montaigne or Diderot, they can't easily make them swallow, like so many thrushes, all the affronts of the American way of life" (235). First comes "Buvez Coca-Cola," then comes "Make love like a cowboy" (239). Language was essential to cultural identity. This Sorbonne professor, who was not highly regarded by the intelligentsia, was not above sheer nastiness when describing the United States. He related personal incidents that demonstrated Yankee anti-Semitism and racism, suggesting that in borrowing language one also imports another society's vices. There was even an invidious comparison with the Nazis.[12] In his view Americans offered the French a choice—either speak franglais or disappear as a nation. To which Etiemble preached cultural resistance. Indeed not only de Gaulle's government, but also those of his successors in the 1970s and 1980s, made efforts to guard the language. This theme of a cultural war was to gather momentum in the next decade.

Expressions of Gallic cultural superiority, like those of Etiemble and Bosquet, were commonplace. Even prolonged visits to America did not always allay such astringent perceptions. When a congressional advisory committee in the early 1960s assessed the State Department's overseas cultural activities, including its academic exchange program, it found that of all the nations involved France was the exception.[13] The reaction of French participants to the exchange was distinctly less favorable than the attitudes expressed by any other nationality. A higher proportion of French exchange scholars criticized American education, art, and music and doubted that the experience had been personally or professionally rewarding. Why were the French the exception? The answers given by the congressional report are familiar: French esteem for their own culture bred disdain for other cultures, damaged national prestige, and bred defensiveness; humanistic training made them unappreciative. The State Department, according to one recommendation, should modify its exchange program by inviting scientists and engineers rather than humanists. The latter seemed overly defensive about their superiority and made anti-Americanism their favorite sport.

Political assaults, as well as cultural aversion, persisted in the 1960s. Charging the United States with imperialism was a course available to

both right and left. On the right there were Gaullist polemics against the hegemonic pretensions of the United States in Europe and around the world. One Gaullist tract claimed Washington's diplomacy was subservient to corporate giants, making NATO a "colonial pact." American capitalism, from this partisan perspective, was a danger to world peace because its boundless desire for profits and power could escalate into war, genocide, and even a nuclear apocalypse.[14]

The left, as much as the Gaullists, targeted the United States as an imperialist danger. Colonial wars fought by the French in Indochina and Algeria and by the Americans in Southeast Asia heightened sympathy for the plight of the Third World. American military intervention in Vietnam made anti-imperialists of an entire generation who recoiled at the horrors of napalm and rejoiced at victories of a Third-World David against the Yankee Goliath.[15] At the same time Socialists like Gaston Defferre warned of American imperialism encroaching on Europe via foreign investment and preventing the emergence of either an independent or a socialist Europe.[16] A notable example of this neoimperialist critique came from a reporter who covered America for Le Monde, Claude Julien. The latter spoke less for student radicals than he did for much of Le Monde 's readership.

Julien had studied at a Midwestern university and written extensively about the United States before publishing his celebrated book in 1968 entitled L'Empire américain . In an earlier study, relying on C. Wright Mills, Julien had analyzed the American power elite and emphasized the shadows that fell over the American way of life—racism and poverty, waste and consumerism, megalopolis and suburbia.[17] In his 1968 book Julien predicted the demise of this "American empire," noting its internal turmoil and the contradiction between skimming off the resources of the globe while preaching the American way to the Third World. If Americans accounted for only 6 percent of the world's population, they consumed the bulk of such resources as oil and metals. The gap between the rich and poor nations was growing and the United States had come to rely on dictators and military force to protect its access to raw materials. Increasingly, internal and external reality contradicted the American dream.

To Julien the American model was inappropriate for Europe. Adopting American techniques such as management or mass advertising, as some urged, would be insufficient to give Europe a standard of living similar to that of the United States. For Europeans to attain American prosperity, they would need access to a comparable volume of raw

materials imported from the Third World at prices profitable to the industrialized north and ruinous to the underdeveloped south. Europe following America's strategy would end up with a puny version of the American dream and help precipitate a confrontation between the rich and poor nations. Imitating America would make Europeans accomplices in neoimperialism and earn them the wrath of the Third World—just what the United States faced in Vietnam.

Le Monde 's reporter thus took issue with Gaullist economic strategy, which appeared to be fostering American consumerism, and tried to design a leftist alternative. "It is not indispensable to enter into the frenetic circle of consumer society to assure economic expansion," he wrote.[18] We do not need a new car every two years; and we do not need to consume a kilogram of newsprint every Sunday. Julien urged Europeans to develop sectors that Americans seemed to neglect such as leisure, culture, public works, and education. Economic growth need not come from expanded internal consumption alone—instead of manufacturing cars for the French, the automobile industry could build tractors and farm machinery to sell to the Third World.

L'Empire américain thus linked economic imperialism to consumer society. "Consumer society does not exist without empire and it will collapse with it" (507). Julien resisted the American model of consumer society because it gave prosperity to the privileged few at the expense of three billion other human beings. He also rejected the American model because it transformed society into what David Riesman called the "lonely crowd."

Presented as a paradise, consumer society carries in itself its own hell, with its areas of poverty, its expressions of racism, its injustices, its sometimes unbearable tensions, its hypocrisies, its neuroses, and its explosions of violence (510).

Fatally linked, consumer society and neoimperialism faced a violent end.

Such neoimperialist analysts, among whom were the Communists, continued to contend that America was guilty of exporting its benighted capitalist model to the rest of the world.[19] While these theorists ascribed American expansiveness to a need for cheap resources, other leftist critics attributed it to American arrogance—to Americans' sense of being the chosen people who exported their consumerism because they assumed they were making others happy.[20] Here was the thesis that America imposed its system on the rest of the world under the cover of a universal mission to make others free and prosperous. For most French critics the big American ego was difficult to accept.

In general leftist-inspired anti-Americanism modulated during the 1960s despite the anti-imperialist demonstrations of student radicals and the attacks of writers like Julien. This occurred in part because of Gaullist usurpation of the terrain. If de Gaulle was anti-American, then the left had to reconsider its position.

Le Monde, the anti-American voice of St-Germain-des-St-Germain-des-Prés, no longer systematically criticized Washington's foreign policy and refused, as we have seen, to give de Gaulle's anti-American policies its unqualified support. The newspaper shifted to reporting rather than editorializing about American society and politics. There were ironic, even caustic, comments about America, and an air of disapproval still informed its pages—Beuve-Beuve-Méry after all remained editor and Julien was one of its authorities on America—but the newspaper was gradually exchanging Cold War antipathy for a more nuanced stance.

At the same time Les Temps modernes, Sartre's review that had once devoted considerable space to unmasking America, came to discount the United States as an unredeemable society. Where the review once carried long critical studies like those by Simone de Beauvoir and Claude Alphandéry, it now published occasional pieces on subjects like the John Birch society, the Weathermen, or black revolutionaries as it took note of the emergence of American fascism or its opposite, leftist militancy. Otherwise Les Temps modernes ignored America.

Far more significant for the evolution of the left's perception of American society than the contemptuous neglect of Sartre's review was the mellowing of Esprit, the other major interpreter of America for the intelligentsia. One might even speak of the conversion of its editor, Jean-Marie Domenach.

Domenach's review of Julien's Empire américain, in which he found Julien's reasoning mistaken—calling it a kind of mechanistic, Leninist interpretation of imperialism—but approved his conclusions, is illustrative.[21] To Domenach the underdevelopment of the Third World was not, as Julien believed, simply the result of American imperialism. Europeans were also responsible. Nor did the United States, given the Soviet invasion of Prague, monopolize imperialism. Julien was correct, however, in concluding that Europeans should reject an imperialism that resorted to violence, destroyed Third-World cultures, and endangered world peace. The danger of the American empire for Europeans was more subtle than Julien realized. It was not, like the Vietnamese conflict, a matter of open combat. Resistance took another form. To resist being

enveloped, Domenach counseled, Europeans must strengthen themselves culturally and morally.

Julien's crude anti-Americanism, in the view of Esprit 's editor, led him mistakenly to condemn all Americans. Universities in the United States, which Domenach came to know from his frequent visits during the 1960s, were havens of anti-imperialism. Moreover, America was Europe's daughter and carried many of the parent's values. And Domenach applauded America for its new voices of dissent, whose "style of life is opposed to everything that we detest in the United States"; its social experimentation; and its capacity for self-correction.[22] Americans, for example, would probably face problems like pollution before Europeans did.

Despite his new sympathy for America and his comprehension of its diversity, the editor of Esprit remained an irreconcilable critic of America's frenetic pursuit of production and consumption. He reproached consumer society for "debasing human beings and human relations by systematically exploiting every element of covetousness." He evoked Heidegger to liken consumerism to the "descent of being and its submersion in things."[23] It sterilized man's creative and emotional powers; it divided mankind into races, classes, and developed as opposed to underdeveloped countries; it brought waste, overcrowding, and pollution; and it formed a "society of domination" in which a social order based on affluence served ruling elites. Pollution, crime, and drugs evoked not a Marxist economic crisis but a moral and spiritual crisis. "A society oriented toward material enjoyment and increasing the standard of living secretes such poisons."[24] It is no surprise that Domenach applauded the students' protests of 1968 and hailed them as victories for free speech and imagination and for what he saw as a rejection of consumer society. He proclaimed that "the critique of consumer society has moved into the streets." Domenach construed 1968 as "the first post-Marxist revolution in Western Europe." "Europe . . . has sketched the first response to the fascination with Americanism."[25]

Yet for all these misgivings, to the editor of Esprit, America announced Europe's future. In fact, "American society is already half installed in our future." He pleaded:

As long as our society does not show that it has chosen a path different from the one already chosen by the United States, all the sad truths that one must tell about the United States will concern us equally. We shall have their crimes. Could we also have their universities?[26]

Just as Domenach became more receptive to America, various of his colleagues on the left discovered the "other" or "good America" at the end of the decade. For leftists an "imperialist" America was even more hateful than an anti-Communist America, but a "revolutionary" America, especially one attacked by the Gaullists, made them question their assumptions about the fortress-of-world reaction. The left's stereotype of America, along with its Marxist dogma, concealed this discovery from some who continued to dwell on America's underprivileged and exploited—the victims of capitalism and affluence. But others found a new revolutionary camaraderie across the Atlantic. The radicals of the 1960s discerned an ideological fellowship with the civil-rights movement, antiwar militants, radical ideologues, feminists, black liberationists, hippies, dropouts, and other members of the new American counterculture. French students borrowed what they believed represented American counterculture—including jeans and the music of Bob Dylan and Joan Baez—and honored blacks as victims of the system.

Perhaps the most acclaimed examples of this new discourse from the left were Edgar Morin's Journal de Californie and Jean-Jean-François Revel's Ni Marx, ni Jésus, which appeared simultaneously in 1970.

Morin, a prominent sociologist of contemporary culture, held solid leftist credentials even though he had long since broken with Marxism. Despite his preconceptions Morin discovered during his 1969 stay in California that he liked America, or elements of it, though he continued to profess the standard list of grievances about imperialism, racism, materialism, gadgets, and vulgarity—for example, the pet boutique in San Francisco that sold pearl necklaces for dogs. America was "the most barbarous of civilized countries, but also the most civilized of barbarous countries (all countries being barbarous)."[27] In Morin's eyes, Americans seemed obsessed with organization and function to the point that the disorder of an Italian grocery in La Jolla seemed like an "oasis in this geometric desert" (50). If he once had no sympathy or interest in America, Morin's visit to California made him confess, "I love America" (76).

America, according to Morin, faced internal rupture. The most advanced country in the world was also confronting "the first symptoms of civilization's inevitable crisis" (136). In Morin's view it was precisely because America was the most advanced bourgeois, bureaucratic, capitalist society that it was also fostering real revolution (162). The Apollo astronauts watching Los Angeles strangle in its own smog became a metaphor for America's social contradictions. Similarly Morin stressed that the nation fighting an imperialist war in Vietnam was also generating

a powerful peace movement. And if Americans massacred civilians at My Lai, Time magazine also published an examination of conscience about the massacre that, in Morin's view, had no parallel in any French journal during the Algerian war. For "America is not only the country of imperialism, it is also the country of the adolescent crusade" (262).

This "adolescent crusade" captivated Morin, who plunged into California's counterculture by attending peace demonstrations and rock concerts and by visiting communes. Young people attracted his admiration because of their social and cultural experimentation that aimed at inventing a new way of life. The French sociologist perceived that this revolt grew out of individualistic, bourgeois consumer society; but it also broke with this society because it opposed an individualism of sensation, joy, and exaltation to an individualism of property and acquisition—"the hedonism of being (the cultural revolution) radically opposes the hedonism of having (bourgeois society)" (134).

He realized that this revolt against the American way of life was American too—for it emerged from an American sense of brotherly and sisterly goodness and openness. Morin reveled in the hedonism of California of the 1960s, the commingling of the races, the free and easy ways of the "flower children," while sensing a tragic naivete and even destructive introversion in their reliance on drugs. And repression seemed imminent to him in 1969 because what once appeared as social deviance now loomed in the eyes of the majority as a threat to the American way of life. "These Anglo-Americans devote themselves with industry and seriousness to efficiency: they are the leaders in technologizing the world, but they don't know how to live, and the art of living will come from those they despise" (149).

What America's young rebels disliked about their society, in Morin's analysis, were those features of America that the French left had habitually scorned. Yet their dissent was more cultural and existential in character and aimed at revolutionizing a way of life, whereas the rebellion of French student radicals was more ideological. Morin hoped American youth could shun the suffocating dogma of Marxism and maintain their innocence. "The young are saving or killing American society. Or rather they are saving and killing it at the same time" (231).

When another prominent intellectual from the left went a step beyond Morin and proposed America as the prototype of the only truly revolutionary society, as did Jean-Jean-François Revel in Ni Marx, ni Jésus, then one might conclude anti-Americanism was fading within St-Germain-des-St-Germain-des-Prés itself—that Parisian quarrier most associated with Yankee-baiting.

To be sure, Revel was something of an enfant terrible known for his pugnacious attacks on the establishment. Still he was a respected man of letters and a well-known journalist writing for L'Express . In Ni Marx, ni Jésus he provocatively hailed America as the land of revolution in order to display what was wrong with France. Revel regarded the left's anti-Americanism as a symptom of its own paralysis. The French left was committed to ideological purity, not action. "The Holy Grail of socialism has attained a state of such ineffable purity that there is no place for it anywhere in the present social situation."[28] Revolution could not come from those who also took pride in being antiscientific and antitechnological as well as anti-American. Gaullism fared no better in Revel's view—he found it archaic and authoritarian. Left and right, according to Revel, kept France from advancing.

As Morin did, Revel contested the left's stereotype of America as fascist, racist, and conformist. Europe killed twice as many Jews as those now living in the United States, Revel observed, yet the left dared to label America as anti-Semitic. And Europe, not America, gave the world Hitler, Mussolini, Franco, and Pétain. Revel criticized the left for its doctrinaire anti-Americanism and cited Le Monde for its slanted reporting. At the anecdotal level he recalled a conversation with a friend who said Americans were uncultivated and prudish; Revel had taken exception to his remark, citing data that Americans read more books than the French. His friend's only response: that was because most of the books Americans read were obscene.

But in America there was hope. For in the New World the voices of dissent were far stronger than anywhere in Europe, and America possessed the economic and technical leadership to support revolutionary change, as well as the freedom and respect for law to permit it.

The United States is the country most eligible for the role of prototype nation for the following reasons: it enjoys continuing economic prosperity and rate of growth, without which no revolutionary project can succeed; it has technological competence and a high level of basic research; culturally it is oriented toward the future rather than toward the past, and it is undergoing a revolution in behavioral standards, and in the affirmation of individual freedom and equality; it rejects authoritarian control, and multiplies creative initiative in all domains—especially in art, life-style, and sense experience—and allows the coexistence of a diversity, of mutually complementary alternative subcultures (183).

Revel asserted that "the American left is probably the world's only hope for a revolution that will save it from destruction" (127). For in America there was the black revolt, the feminist attack on masculine

domination, the youthful rejection of exclusively economic and technological goals, concern about poverty and the environment, a movement for consumer protection, and a radical new approach to moral values. And, most important, the antiwar movement was destroying imperialism from within. The common basis for this dissent, according to Revel, was rejection of a society dominated exclusively by profit and ruled by competition. In the American counterculture human beings were once again an end and a value in themselves. Revel's version of Montesquieu's Persian Letters found in America the prototype of the good modern society. He concluded, provocatively, that Europeans' self esteem made it impossible for them to admit that Americans were more civilized, democratic, and revolutionary than they themselves were (188).

In retrospect we can see that this discovery of the "other America" by leftist intellectuals like Domenach, Morin, and Revel, as well as Gaullist usurpation of Yankee-baiting and the Soviet's waning star, initiated the gradual retreat of anti-Americanism among those who had been the strongest source of criticism. The magnitude of this shift can be seen in Morin's preface to a translation of David Riesman's Lonely Crowd .

American society has ceased to be an "impossible" society for us, a society without political parties and structured ideologies, without any revolutionary protest, containing only technocrats in "human relations" and "public relations." . . . We sense that, from the point of view of civilization, America not only preserves the present of Western civilization, but also the future of the human race.[29]

America was receding as a target for the leftist intelligentsia.

Along with the mellowing of the left, of equal significance for the future was the growing enthusiasm for the American model. I employ the term "Americanizer" for this perspective without implying that its proponents intended to meet le défi américain by indiscriminate imitation. To a striking extent these enthusiasts were drawn from the ranks of public officials, managers, and social scientists rather than the literati.

For the Americanizers there was an alternative to resistance. Americanization, they contended, was essentially a global imperative and, on the whole, a beneficial process that could be tamed and adapted to preserve the French way. Selectivity and lucidity were the keys.

These self-styled realists recognized that Americanization might be accompanied by various afflictions: the fetishism of products; a constant

escalation of unsatisfied desires; cultural homogenization; a pampered but restless youth; dependence on alcohol, drugs, and psychoanalysis; and impending ecological disaster. But the analysts believed that these assorted pestilences could be avoided or mitigated and that the benefits outweighed such troubles.

An author of a college text on American civilization, for example, rejected extreme interpretations of Americanization.[30] It was not an apocalypse, according to this expert, and the accounts of theorists like Simone de Beauvoir and Cyrille Arnavon were distorted by passion and politics. He debunked the notion that the French were any less materialistic than the Americans and scoffed at the Gallic rationalization of a richer spiritual or inner life. Like it or not, America was the model of global development; Europeans could either accept and adapt to it or passively submit and sacrifice their identity.

The national economic planning agency, founded by the ardent Americanizer Jean Monnet, championed the modernist stance. Officials in the agency who in the early 1960s were trying to map out the future shape of France had to address the imminent confrontation with America. One such expert, Bernard Cazes, pointed out that it was unfair to trivialize consumerism as the pursuit of artificial needs. The family of the 1960s might be not only comfortable but also happy in its dreamlike world of consumer products. Cazes stripped away the irrelevant moralizing about consumer society in order to present it as an economic mechanism constructed around rational human choice.[31]

These planners, taking their cue from the Gaullist government, insisted that in order to be competitive France would have "to imitate an economy that surpasses Europe in growth." At the same time they also wanted to design "an original society" different from that of the challenger.[32] They believed that the richness of Europe's traditions and its different scale of values would virtually "guarantee that the structure of consumption" in France would be different from what existed across the Atlantic. In order to reach "a new civilization" and ward off the American menace, the planners sketched a social-economic future based on growth, high consumption, and competitiveness that also paid attention to public goods and services, the quality of life, aesthetics, and the participation of citizens in the collective effort of remodeling the nation. Pierre Massé, who headed the planning agency at the time, took issue with the consumer society and tried to define "a less partial idea of human beings."[33] Many social scientists, who on balance saw more virtue than vice in the New World, also contributed to what

was both a "modernist" affirmation of America and a critique of French institutions.

During the 1960s publishers like Seuil and Gallimard made available translations of the work of such American social scientists as David Riesman, John Kenneth Galbraith, and William A. Whyte, which offered a critical arsenal to assess contemporary society. Translations also appeared of studies about France written by American or European-born social scientists living in America. Publication of A la recherche de la France, for example, made available the critical assessments of French institutions by experts like Stanley Hoffmann, Charles Kindleberger, and Laurence Wylie.[34] Indeed the very concept of France as a "blocked" or "stalemate society" with its internal rigidities, compartments, privileges, and hierarchies that impeded "modernization"—a term that connoted a dose of American-style decentralization, self-reliance, and mobility—was a contribution of authorities like Hoffmann and Michel Crozier. Crozier, who was the sociologist most closely associated with this critique, largely drew his conception of French resistance to modernity from his experience in the United States and his knowledge of American social science.

By the 1960s Crozier had earned a reputation as a gadfly of St-Germain-des-St-Germain-des-Prés. He was one of the principal interpreters of both America and its social science to the Parisian intelligentsia. Writing about a foreign country in order to critique one's own society became a French literary genre even before Montesquieu's Persian Letters; Crozier, like Revel, made good use of this literary technique.

Examining the intellectual climate of America in early 1968, Crozier chided French leftists who pictured the United States as a "brave new world" run by trusts and technocrats and smothered by comfort and conformity. "Nothing is more false," he wrote, than to conceive of contemporary America in the mode of William Whyte's Organization Man . "Men of action in modern America have never been less conformist."[35] What was striking in 1968 was not complacency, as in Eisenhower's America, but "the aggressive confidence in human reason and in the American capacity to use it to solve all problems" (7). The French sociologist cited the heightened rationality of American managers to calculate and adjust means to ends. The hero of this new managerial rationalism was Robert McNamara, who brought to government techniques developed in private industry. It was Europeans who suffered from the timidity of "the organization man"—weighed down by the closed world of the administrative corps and elite schools. It was America

that was run by young Turks—for example, the innovative scientist who, blocked by his employer, found venture capital to build his own firm.

After criticizing both the intelligentsia and the managerial and bureaucratic elites of France, Crozier turned to American counterculture to demonstrate that America was advancing in still another way. The progress of hyperrationality, the "harsh sun" of calculating cost-efficiency, the French sociologist acknowledged, disturbed America's youth. He recommended to Americans that they allow more room for inefficiency and spontaneity, so that participants could tolerate the rigors of the new managerial rationality. The psychedelic bohemia that captivated the young proved not that America was sick, but that it was "in the process of a profound shift" (5). America was once again on the move. Conversely, France was not.

That Crozier's essay appeared in Esprit, as did excerpts of Morin's journal, suggests the extent to which the intelligentsia had evolved in its thinking about America. An even more prominent spokesman for this cautiously affirmative position was yet another social scientist, Raymond Aron, who did not address America directly but treated it as the most advanced example of "industrial society"—a category that embraced all Western societies.

Industrial societies, according to Aron, were all caught up in the same dynamism of economic growth, technology, and scientific research; they consumed the same products, used similar management techniques, and mixed state intervention with market forces. Differentiation within this class of societies was essentially cultural. The basic choices within these Western societies over such questions as private consumption versus public service were not polar opposites but decisions about shares. Europeans, Aron believed, would, as they had in the past, continue to choose different alternatives than Americans did. "Whether successful or not, resistance to certain aspects of American commercialism will continue in Europe, at least verbally."[36] Aron himself awarded high priority to these cultural differences: "What must remain inviolate is not progress or the rate of growth, but culture—that is, the totality of works of the mind" (204). He refused to predict to what extent technology was going to dilute cultural diversity, but he was skeptical about the prospect of a coming universal civilization, since the goal of culture was a unique way of life and a singular expression of creative freedom.

Like the other "realists," Aron reflected on both the promise and the penalties of economic development. If material well-being was a prerequisite for the good life, he asked, "in what does the good life consist?"

and "who defines it?" The ultimate source of disillusionment with economic progress was the continuing conflict over modern values—equality, personality, and universality. Expanding production did not automatically solve social problems or give individuals a reason to live. It often made things worse. It created new losers—the young and old, the unskilled and the disadvantaged—all those who could not compete and who went unrewarded. And the consumer was bombarded by the media as ever rising targets of consumption evoked envy and even anger from those who felt deprived. Even the richest nations like America had not satisfied people's wants because desires escalated along with rising productivity. And the whole system devalued personality. "Just as each individual aspires to equality he also aspires to individuality," Aron wrote (xv). "The world in which industrial man must live has lost its enchantment," he concluded (203).

A measure of the shifting mood was the growing popularity of Aron—whom Domenach had once debunked as "the sociologist of Le Figaro, " a conservative paper. Aron's book on industrial society appeared in Gallimard's paperback series and sold over 50,000 copies. And his success was greeted with approval from some quarters on the left. Pierre Nora, for example, wrote in 1963: "Aron has surpassed Camus. Does industrial society interest the public today more than Sisyphus? Let's accept the omen."[37]

Within the ranks of the Americanizers, in contrast to Aron's subtle and almost tortured assessment, was the rooting section of unabashed enthusiasts. These included familiar names like the influential Jean Monnet and the prolific Jean Fourastié.[38] Since the days of the productivity missions, the former had been preaching the American way to public officials. "The French," Monnet lectured, must learn to accept "the psychology of Americans," that is, "the disposition to change constantly."[39] And in his popular books the economist Fourastié had been telling the French about the promise of the coming postindustrial society. If the leap to the future required a stage of turmoil and confusion, Fourastié predicted a new stability would be reached when people would enjoy brief work days and more leisure and education. He believed that as time went by the novelty of consumer goods would fade and individuals would choose to consume less and do more. The "tertiary civilization will be brilliant, the machine letting human beings specialize in things human."[40]

Equally sanguine about the future were prominent managers from both the private and public sectors like Jean St-Geours and Louis

Armand. Here we encounter a veritable celebration of Americanization—but a celebration that also recognized risks. St-Geours, who made his career in public finance, wrote a personal testament, Vive la société de consommation, that charted the progress of industrial society in lifting humanity from its present needs and fears by providing a high standard of living and greater freedom to address its problems.[41] We shall pass through the materialistic phase, he wrote, and in the postindustrial future the modern individual will be freer, better informed, more confident, and thus better able to fulfill higher personal, and even spiritual, goals. At the same time St-Geours rhapsodized about such consumer products as television and the automobile. He expressed his delight about a Sunday drive to the Loire valley with his car radio playing Beethoven. Armand, who had modernized the French railways after the war, pointed out that no one was forcing Europeans to Americanize.[42] We adopt American technology—typewriters, television, home appliances, nylon, computers, and ballpoint pens—because we find them beneficial. We do so, he said, because we welcome technology and ignore the costs in congestion, pollution, and upheaval. To Armand the world, whether or not the French approved, was living in the "American era."

The 1960s also witnessed the Americanization of French business management. Executives like Jacques Maisonrouge of IBM-France, consulting organizations like CEGOS (Centre d'études générales d'organisation scientifique), and business journals like L'Expansion proselytized American managerial techniques—but that is a subject unto itself.[43]

For the growing contingent of "yes-sayers," America was a source of inspiration.[44] It had not turned out to be Duhamel's nightmare. The way forward, from this managerial perspective, lay neither in servile imitation nor in systematic criticism but in learning from the American model. Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber, the editor of the newsweekly L'Express, issued this perspective's most widely discussed invitation to Americanization. His book, Le Défi américain, has already appeared in the context of American investment (in chapter 7) but also bears on this discussion because it synthesized and popularized the realist or modernist position.

Servan-Schreiber saw the American challenge emerging from economic dynamism—a dynamism generated by tapping human creativity through organization and education and by rewarding initiative and mastering change. Modern power derived, not from natural resources or capital, but from "the capacity for innovation, which is research, and the capacity to transform inventions into finished products, which is

technology."[45] He praised American management and called the close association of business, university, and government the "basic secret" of American success (168). Servan-Schreiber, citing Michel Crozier, asserted: "The Americans know how to work in our countries better than we do ourselves" (182).

Le Défi américain was a "call to action." Not much time remained for Europe to "counterattack" before it became an American satellite. "If America is the place where decisions are made, and Europe where they are later put into application, within a single generation we will no longer belong to the same civilization" (44). The United States, Canada, Japan, and Sweden would enter postindustrial society, but Europe would not. The choice for Europeans was either to remain passive before the American challenge and become an economic backwater and an "annex of the United States" or to imitate the American way and thus join the race to the postindustrial future.

The stakes were higher than merely maintaining a comparable standard of living. If the day came when American subsidiaries called the tune and Europe's drive for freedom and independence flagged, then "the spirit of our civilization will have broken." "Without suffering from poverty, we would nevertheless soon submit to fatalism and depression that would end in impotence and abdication" (191). American business would one day cross "the threshold of the European sanctuary" and take control of publishing, newspapers, recordings, and television.

[Then the] channels of communication by which customs are transmitted and ways of life and thought formulated—would be controlled from outside. Cairo and Venice were able to keep their social and cultural identities during centuries of economic decline. But it was not such a small world then, and the pace of change was infinitely slower. A dying civilization can linger for a long time on the fragrance left in an empty vase. We will not have that consolation (192).

In order to meet the American challenge France had to compete with the United States in all the essential areas of technology and science. If the French were content with being a big Switzerland, highly specialized in a few areas, he argued, they could eventually have a high standard of living but without developing an autonomous civilization.[46] A European counterattack meant mobilizing the continent's creativity by pooling the region's resources and talent, establishing European-wide multinationals, and creating a truly federal Europe that could formulate, fund, and direct an industrial and scientific policy. Ultimately the counterattack was a matter of political will or ambition rather than economics. Europeans

could meet the challenge if they willed it, if they federated and embarked on internal reforms to democratize and open their societies.

The way forward to postindustrial society required massive social and cultural, as well as economic, overhaul. Servan-Schreiber's notion of France as a blocked society owed much to the work of other social critics such as Michel Crozier and Stanley Hoffmann. The journalist argued that the secret of America's success lay in the confidence it placed in its citizens—in their ability to decide for themselves and in their intelligence. He inverted the Gallic cliché about the gadget society by stating that "American society wagers much more on human intelligence than it wastes on gadgets . . . this wager on man is the origin of America's new dynamism" (253). His message was that the French needed to encourage initiative and delegate authority, for example, to decentralize management and local government. Once their energy and creativity were released, they could "produce phenomenally."

The message of Le Défi was perplexing. Europe must Americanize in order to escape being run by Americans. That is, Europeans must selectively imitate American ways, for example, in the scale of enterprise, management techniques, research and development, education, and, above all, individual initiative. But for Servan-Schreiber such borrowing did not mean the continent should duplicate America. He held out Sweden and Japan as alternative ways to postindustrial society.[47]

When asked if he were anti-American he answered, "It's not a question of being anti-American, but it's not necessary for us to become 'pseudo-Americans.' "[48] Nor did he blame Americanization on America. Europe would have followed the same path even if the United States were lagging rather than leading:

The contempt and distrust of America felt by many Europeans is really their own fear of a future that was chosen by their fathers when they launched the first industrial revolution, and which they themselves reaffirmed by starting the second (193).

Thus he urged Europeans to study and imitate America without offering it as a model.

Virtually every review of Servan-Schreiber's book agreed that there was a dangerous American challenge and that he had correctly formulated it as a lag in technology, management, and research rather than capital.[49] The disagreement came over solutions. The most common response was to accept some measure of Americanizing therapy. Among

those who at least nominally endorsed Le Défi 's thesis were managers like Louis Armand and Marcel Dassault; public officials like Jean Monnet, François Bloch-Bloch-Lainé, and Albin Chalandon; and journalists or economic experts like Michel Drancourt, Raymond Cartier, Jean Fourastié, and Pierre Lazareff. Giscard d'Estaing, the former minister of finance (and future president of France) who had once forcefully resisted American investment, had only praise for Servan-Schreiber's analysis and his solutions.[50] A few prominent Socialists, among them Gaston Defferre, who had been the candidate of L'Express for president in 1965, praised the book. Spokesmen for corporations like IBM-France, however, preferred to let existing multinationals lead the way rather than create new Eurocompanies.[51] Just as Servan-Schreiber took exception to the Gaullists' handling of the problem, others, mainly on the left, disapproved his remedies.

Such critics, including Claude Julien, were quick to fault Le Défi for preaching Americanization as the way to resist America.[52] François Mitterrand, then head of the Fédération de la gauche démocrate et socialiste, echoed the alarm Le Défi sounded, but objected to finding a solution in a liberal rather than a socialist Europe.[53] Others argued that Servan-Schreiber's conception of Europe was too "capitalist" to assure either independence from America or a social democratic future. His rejection of nationalization, his neglect of class analysis, and his disregard for the Soviet Union, from this perspective, seemed wrongheaded. The Communists likened Servan-Schreiber's notion of a European community to a capitalist club and saw no solution in merging French monopolies with other European monopolies.[54] The proper response, for the Communists, was to build socialism on a national basis.

It should be no surprise that many of those who responded to Le Défi found French civilization at risk. The emphasis was, borrow if we must; but find another path to development than the one blazed by America. Thierry Maulnier of the Académie française, for example, acknowledged that the United States had become a global model, even for Socialist countries, but he contended that Europeans should use their values to chart an alternative to the Americans' endless pursuit of consumption.[55]Le Monde, true to form, saw Americanization as cultural self-destruction:

It's not sinning by chauvinism or traditionalism to think . . . that European culture still has a word to say, that it, more than ever, has its values to express, in a civilization that risks becoming, for the first time perhaps in the history of the world, a civilization without culture .[56]

Even a technocrat like Michel Drancourt argued that the French and the Europeans could not ward off America by submission but must somehow give Europe its own personality.[57] Servan-Schreiber had made much the same argument—that transfers from America need not mean duplication of the American model but that some imitation was necessary if Europe were to survive as an independent civilization.

The controversy stirred by Le Défi américain in 1967–68 expressed Gallic alarm over American expansion, especially over a threatened economic independence and an endangered national identity. Response to the best-seller suggests growing acceptance of a measure of Americanization as the necessary therapy.

During the 1960s while de Gaulle was correcting the imbalance in Franco-American relations, America lost its centrality in the domestic debate about socioeconomic modernity. The way the intelligentsia construed the issue was to make it more diffuse, as discussion moved away from America toward reflection on subjects like postindustrial society or indigenous problems that accompanied abundance. America had become more a fellow victim of a universal process than the agent of some international disaster. Indeed, Americanization in the form of American products and fads had progressed so far—from McDonald's and jeans to franglais and pop singers with American names like Johnny Hallyday—that familiarity seemed to dampen anxiety. There were those, to be sure, on the left and the right, from Claude Julien to René Etiemble, who continued to blame the United States for exporting its economy or its culture. But most of those who interpreted the coming modernity excused America or made it merely the most advanced example of a general development. Thus Raymond Aron's judicious and cautious assent became representative of the new discourse. Most believed France could adapt to American ways and some welcomed a healthy dose of Americanization to open French society and its economy.

On the left, where a new sympathy for America emerged, dogmatic Marxists might continue to rail about monopoly capitalism, but others like Domenach, Morin, and Revel found a common camaraderie of dissent in the two countries. If there was still a "bad America" of technocrats, dollars, and the Pentagon, there was another America—the one associated with the civil rights movement, Berkeley, the Black Panthers, hippies, communes, and Herbert Marcuse—which the left found appealing. Soviet misbehavior in invading Czechoslovakia assisted this turnabout by causing a loss of faith among the faithful. The next

decade would bring the long march of the left away from its revolutionary past and from affiliation with Marxism and would bring it closer to Western democracy and the United States.

The 1960s were an example of historical serendipity. A decade that saw some of the most virulent expressions of anti-Americanism since the early 1950s also reduced acrimony. The 1960s ushered in an era of détente, and not only among the intelligentsia: at the very end of his presidency even de Gaulle softened his tone toward Washington. The decade eased antagonism and nuanced perceptions, opening the way for the new, more affirmative, mood of the 1970s and 1980s.