Confession as a Political Weapon

In the opinion of the dissenters in the New York group, the literature of ex-Communist confession and disillusionment seemed to go beyond threatening the independence of the intellectual. They felt that part of the harmful function of the ex-Communist lamentations was also to suppress the political left in America. Ex-radical penitence, they believed, had the function of enforcing conformity and undermining leftism at the same time.[118]

In the 1950s, both dissenters and affirmers hoped to discover a way to oppose ideology—in the name of pragmatism—without destroying the political left. Certainly those who still considered themselves leftists could not repudiate ideology as thoroughly as the centrists in the group, since a world without ideology seemed a world without promise of anything beyond the status quo. So the task for the left wing of the New York group was to carve out a respectable position somewhere between rejecting Communist ideological absolutism and accepting a conservative pragmatic world without any ideology whatever. For the dissenters, the years after World War II were a time of searching through the rubble of past political visions to identify what constituted good, as opposed to dangerous, ideology.

Leslie Fiedler's celebration of ex-Communist confessions, "Hiss, Chambers, and the Age of Innocence" (1950), was considered by the dissenters to be not only an endorsement of intellectual conformity but also an unveiled attack on the left and the idea of radicalism. In Fiedler's assessment, Chambers was a hero and Hiss a coward and a dangerous political fool. That interpretation, by itself, was not at odds with the outlook of anyone else in the New York group. Where Fiedler parted company with the dissenters was in his indictment of the liberal left in America for its "moral" complicity in Hiss's guilt. Fiedler barely had enough breath to list all the faults of the liberals, one of whose worst sins was their failure to appreciate the role of the ex-Communist penitents. "All the world distrusts a convert," Fiedler scolded, "but no part of it does so more heartily than the liberals." And the liberals, all of them, were living in a fantasy world. Hiss, Acheson, and Eleanor Roosevelt, like all liberals, shared a "lack of realism" that resulted from an outlook "in which liberals, conservatives (and even radicals) are assumed to share the same moral values." Those on the liberal left were simpletons who did not make the proper distinctions, which led them to conclude that "Communists are 'left,' and everyone knows that only the 'right' is bad."[119] The liberal left, according to Fiedler's account, ignored the mistakes of everyone left of center, which, in the case of the Communists, produced a dangerous travesty.

The dissenters might have been able to go even this far with Fiedler, as they had filed their own brief against the fellow-traveling part of the liberal community, whom they despised as dangerous and intellectually traitorous. But he was more imprecise than those liberals he accused of imprecision, since in condemning the liberal fellow travelers he expanded his attack, in his pirouetting enthusiasm, to the entire left of center. "In the end he failed all liberals," Fiedler charged Hiss, "all who had, in some sense and at some time, shared his illusions (and who that calls himself a liberal is exempt?)." This challenge—"and who that calls himself a liberal is exempt?"—infuriated Harold Rosenberg and prompted him to dust off his intellectual artillery and aim it at Fiedler.[120]

Fiedler was not finished. He challenged leftists one more time before ending his essay. "American liberalism has been reluctant to leave the garden of its illusion," he announced sadly, hat in hand, standing over the grave he had just dug for the left, "but it can dally no longer: the age of innocence is dead." Come, we must be men, all of us, shouldering our responsibility—part of which is a manly soul-clearing confession, on our knees, weeping only softly. "The confession in itself is nothing, but without the confession there can be no understanding, and . . . we will not be

able to move forward from a liberalism of innocence to a liberalism of responsibility."[121]

Despite Fiedlerg pose as the lone prophet uttering the painful truth to a deaf intellectual community, he was shrewd enough to have thrown his fortunes in with that majority of the New York group who were affirmers. He had so much company at his lonely lectern, in fact, that he had to shout to be heard above the others.

As a leading affirmer, Hook agreed with Fiedler about the beneficial effect of repentance, yet he was not eager to see the ex-Communist confessions do serious damage to the democratic left. Looking at the varied group of ex-Communists in America, Hook separated them into two camps: those like the New York intellectuals, who believed that Communism was bad but that the liberal left, on the whole, was good; and those like Chambers, who believed that because Communism was bad, everything to the left of center was also bad.[122]

Dissenters such as Rosenberg disagreed with Hook and insisted on making a finer distinction, finding three camps of ex-Communists instead of two. Rosenberg agreed with Hook about the Chambers school, but divided the New York group into two camps. There were those affirming centrist "ex-radicals" who did not agree with Chambers that everything left of center was to be despised equally but who had departed from their former radicalism enough to wonder, amid the lamentations and confessions of the ex-Communists, whether much on the left was worth saving. And there were the dissenters who opposed the Communists but felt there was something in the radical tradition worth preserving—something that was being undermined by the anti-leftist confessions. Hook did not notice the split between affirmers and dissenters that Rosenberg detected on this issue, or else he chose not to comment on it. In Hook's eyes, the New York group carried on a unified fight against that party of ex-Communists who were mistaken.

Despite the admiration Hook felt for Chambers on many counts—courage, intelligence, refusal to remain a Communist—Hook charged him with being monumentally wrong. He found unpalatable Chambers's portrayal of the New Deal as "a social revolutionary movement," when in fact it was "an eclectic, unorganized, popular reaction to the intolereble evils of an unstabilized capitalism." The Communists infiltrated the New Deal not because New Dealers were operating a conspiracy, Hook believed, but because of the government's naivete[naïveté] and "stupidity." Chambers, absolutist that he was, did not make distinctions. "He recklessly lumps Socialists, progressives, liberals and men of goodwill together with the Communists," Hook complained.

Worse, according to Hook, Chambers now rejected as leftists all those liberals who had long been fighting the anti-Communist battle Chambers currently was waging. This was the least excusable of Chambers's crimes, the least pardonable in the eyes of the New York group. Now Chambers wrote with horror about the piercing screams of the victims of Communism, but he was "silent about the fact that the truth about the Moscow trials to whose victims' screams he was originally deaf was first proclaimed by liberals and humanists like John Dewey"—those liberals Chambers now condemned in the same breath with the Communists. "While Chambers still worked for Stalin's underground, it was they who sought to arouse the world to the painful knowledge he is now frantically urging on it."

Chambers's memory was short, and his ingratitude large. Now he censured liberals for being man-centered and godless, conveniently forgetting that "in his hour of flight, need and political repentance, it was to the party of Man that he turned for aid first of all." Now Chambers stood sanctimoniously on the political right and criticized everyone to the left of center and everything more secular than Christianity. But, as Hook took pleasure in reminding Chambers, "One would have thought it obvious that Franco, Hitler and Mussolini, and other dictators with religious faith or support, have more in common with Stalin and the Politburo than either group has with the liberals and humanists Chambers condemns."[123]

Though Hook was an ally of the dissenters in their attempt to prevent the left from being demolished in the era of confessions, they viewed him with ambivalence. Like the rest of the Commentary majority, Hook was far closer to the Dissent faction than he was to Chambers, but the dissenters saw Hook as a friend in theory rather than in practice. The problem with Hook, for the dissenters, was that he defended the theoretical privilege or "right" of the radical left to exist, rather than joining them in an advocacy of a real leftist vision.

The most committed supporters of the left against the attacks of the ex-Communists were Irving Howe and Harold Rosenberg. Like Hook, Howe scorned Chambers's labeling of everyone to the left of center as Communist. "Socialists," in Chambers's story, Howe wrote angrily, "ultimately, were allies of Communism, even if, in mere fact, they perished resisting it; liberals were socialists in disguise, sapped by Marxism." Howe's anger was increased by the fact that the independent left had undergone repression from those like Chambers when Chambers was a Communist, yet that left was still undergoing repression from Chambers and his type now that Chambers had switched uniforms and was an ex-

Communist. The New York group had been damned twice by Chambers as he catapulted across the political spectrum. Chambers failed to realize that the anticommunist left was not Communist, and that it had long been carrying on Chambers's own current fight. "These delicate designations," Howe complained bitterly of Chambers's portrayal, "prompt one to remind Chambers that a good many 'left-wing intellectuals' of one or another feather—those who truly deserved to be called 'left' and 'intellectual'—fought a minority battle against Stalinism at a time when both he and Hiss were at the service of Messrs. Yagoda and Yezhov."[124]

Central to the defense of the left against the pressures of Chambers and his school of ex-Communism was an assessment of Stalin's role and responsibility in the course of Soviet Communism. If Stalin was not uniquely culpable, if Communism would have become totalitarian without him, then the entire project of the left was merely an exercise that inevitably led to oppression. If, however, Stalin was entirely to blame, if he derailed the Great Experiment, then the logic of the left was acquitted of furthering an entirely preordained totalitarian course. Chambers felt that liberalism, secularism, and the man-centered universe led to the New Deal welfare state, which in turn led to socialism, which was linked to Communism. The New Deal was a fatal first step. Dangerous leftism all started as liberalism and atheism, progressed to Marxism, and then proceeded unwaveringly to Leninism, Stalinism, purges, oppression, and totalitarianism. The New York intellectuals thought Chambers's vision of history was madness. Even the affirmers, most of whom had all but abandoned their former radicalism, thought Chambers's view of the left was fanatical.

There was obviously a great deal at stake (future politics, ideas, self-respect, influence, intellectual power) for those involved in the struggle over the correct interpretation of recent history—particularly about whether a predominance of leftism, liberalism, or conservatism had led to the totalitarianism of the previous decades. Murray Hausknecht felt that some ex-Communists and their supporters were trying, through their interpretation of liberalism and by their penitence, to remove the latitude and ambiguity in social values necessary not only for independent intellectuals to exist, but also for the left to remain viable. Many ex-Communists, according to Hausknecht, felt that "this ambiguity which seemingly gives a foothold to hostile ideologies must be eliminated." That, according to Hausknecht, was the function of Whittaker Chambers.[125]

Rosenberg agreed with Hausknecht and thought Fiedler as dangerous as Chambers to the liberal left. Why, he asked, was Fiedler's criticism

launched in the name of liberalism? "I, too, believed that Hiss was guilty, but so had the jury, he was in jail; so why these profound evocations of his perfidy, and of Chambers' ordeal and triumph, by a 'liberal'?" As Robert Hatch had said of The God That Failed : "it is evidence in a trial that has long since ended."[126] The trials were already finished and the case closed before the penitents began their lamentations and hosannas.

Fiedler, Rosenberg concluded, had usurped the name liberal for himself, though he was a centrist conservative who opposed the left—in the same way that Communist fellow travelers had also misappropriated the term. Now Fiedler condemned all liberals to share "the guilt for Stalin's crimes through the fact alone of having held liberal or radical opinions, even anti-Communist ones ! For Fiedler all liberals are contaminated by the past, if by nothing else than through having spoken the code language of intellectuals." Like Chambers, Fiedler failed to make crucial intellectual distinctions. But Rosenberg would not accept the guilt that Fiedler pushed his way. "To his question, 'Who is exempt?'" retorted Rosenberg, "I raise my right hand and reply that I never shared anything with Mr. Hiss, including automobiles or typewriters; certainly not illusions. . . . Here I insist that it was Chambers who shared things with Hiss, not 'all liberals."' By lumping together everyone to the left of center with the Communists, as Chambers had done, Fiedler had committed "slander ex-Communist style." Had Hiss fallen to his knees and confessed for "all liberals," as Fiedler recommended, Rosenberg concluded that the judge should have tacked "an additional five years" to his sentence.[127]

In sum, Fiedler was wrong on three points, according to Rosenberg. First, liberalism was not responsible for the crimes of Communism, for one could find no way in which "a belief in freedom, equality, individuality" would lead anyone to support Communist oppression. Second, the liberal left was not to be equated with fellow-travelers, the latter of whom Rosenberg believed to be truly guilty. The fellow travelers were "scoundrels" who had failed to be "open-minded" and had not maintained the proper function of intellectuals. Third, and by far the most important, Fiedler neglected to credit the independent left, those anti-Stalinist intellectuals in the New York group and elsewhere, for their pivotal and successful fight against Communism during the previous two decades.

The reason that the anti-Stalinist New York intellectuals had been excluded from the story by Chambers, Fiedler, and others, Rosenberg charged, was that these latter detested the forces of independent radicalism more than anything else. Chambers's hatred derived from his absolutism. In Fiedler's case, who could tell? "Like their master in Moscow," Rosenberg wrote defiantly, "the Communist intellectuals in America detested above all, not capitalism nor even fascism, to both of which the

switching Party line taught them to accommodate themselves—their one hatred which knew no amelioration was toward the independent radical." Just as the Soviet Stalinists had erased the anti-Stalinists from their official version of history, so in America, Rosenberg argued, the Stalinists (and, as in the case of Fiedler, some liberals) were attempting to excise the anti-Stalinist left. "To the antipathy officially demanded by the Party toward its foes on the Left, the sordid Leftish mass added its own spite toward the outsiders who undermined their revolutionary conceit."[128] So, according to Rosenberg, it was the New York group—the Trotskyists, the independent radicals—who were the most abhorrent to the Communists and ex-Communists alike.

All of this led Rosenberg to conclude that the ex-Communist confessions were useless, of no value whatever except to attack the left. All the ex-Communist confessions were unneeded, Rosenberg felt, because the anti-Stalinist New York group had already defeated Communism in America years before. In fact, "Communism in the United States had been rather decisively defeated as an intellectual current long before a single ex-Communist had voided his memory from the witness stand," Rosenberg wrote with pride. "The Communist who 'passed' into an Ex is himself, very often, the product of this criticism."[129] Chambers, in other words, was converted by the anti-Stalinist New York intellectuals, not by God, to ex-Communism.

Thus three themes dominated the New York intellectuals' responses to the canon of ex-Communist repentance literature. First, they worried about the faith and absolutism that they saw among the missionary ex-Communist confessors, and the prospect of that continued dogmatism fueled their anti-ideological outlook and reinforced their pragmatism. Second, they perceived in these confessions a threat from Communism and ex-Communism to the role of the intellectual, and it prompted them to split ranks on which of the threats was a greater danger. The affirmers thought the confessions were the best defense against the anti-intellectualism of Communism. The dissenters felt that the confessions themselves were an even more dangerous threat to intellectual independence. Third, the affirmers felt that the confessions represented the honesty and integrity necessary to keep the intellectual project healthy in America, while the dissenters thought the confessions had the potential to repress the latitude necessary for intellectual dissent, and to repress and undermine the already shaky foundation of the intellectual left in America. The dissenters suspected many of the affirmers of supporting the confessions in order to rid the country of the left that the affirmers had since abandoned.

Throughout their debates, one sees again that the New York group was

more committed to intellectualism than politics, especially radical politics. Although the affirming majority was not particularly concerned about whether the confessions would be used as sticks to beat the political left, virtually all members of the group did care strongly about the effects of the repentance movement on the intellectual's function—even though they disagreed about those effects. As they had in their opposition to the Waldorf Conference, they gave their intellectual identities and values precedence over their political identities, especially over their old commitment to political radicalism.

The polemics over political ideology and absolutism in the decade after the war exposed raw and sensitive nerves. It had been painful for the New York intellectuals to fight excessive ideology, fellow traveling, and irresponsible leftism at the Waldorf Conference, although they did so with a grim enthusiasm. It had been difficult to live with the ongoing tensions between affirmers and dissenters over issues of political conformism, proper anticommunism, and appropriate levels of dissent against their own culture. It had been hard for them in the decade after the war to reexamine their own past in light of the new literature of repentance, and to continue to wage the battle against inflexibility and ideology.

In the bitter morning light at mid-century, the New York group became increasingly ready to turn its intelligence and energy away from the fatiguing political arena and toward new and less painful problems. They discovered that cultural issues would allow them to exercise their analytical intellectual function without having to focus on the discouraging aftermath of the recent European crises. The topic of cultural issues, particularly criticism of mass culture, was one on which most members of the group agreed—it united affirmers and dissenters more than almost any other issue. Cultural issues, in the painful gray dawn, were easier to face than political issues, and cultural criticism allowed members of the group to write about political concerns without really seeming to do so.

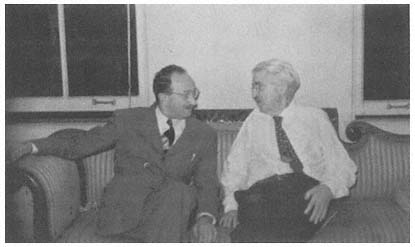

Sidney Hook and John Dewey in a photo taken by Hook's son in 1949. Hook

wrote his doctoral dissertation under Dewey at Columbia University in the late

1920s, and in the 1930s and 1940s the two men joined to oppose totalitarianism

and absolutism. Courtesy of Ernest B. Hook.

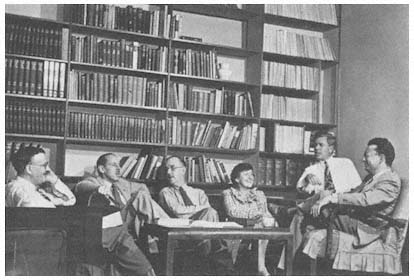

Freda Kirchwey and some of the editorial staff of the Nation in the mid-1940s.

A constant antagonist of the New York intellectuals, who thought her too sympathetic

to the Soviet Union, Kirchwey argued with Sidney Hook and Dwight

Macdonald about their criticism of the Waldorf Conference. From the left: associate

editor Keith Hutchison, managing editor J. King Gordon, drama critic Joseph

Wood Krutch, editor and publisher Freda Kirchwey, associate editor Maxwell

Stewart, and Washington editor I. F. Stone. Courtesy of the Schlesinger

Library, Radcliffe College.

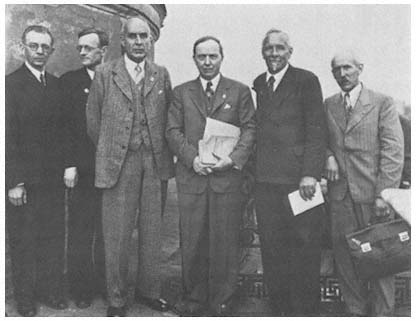

Harlow Shapley (third from right) in June 1945 as Harvard's representative at

the 220th anniversary of the Academy of Sciences in Moscow. An adversary of

the New York intellectuals during the Waldorf Conference, which he chaired,

Shapley was a professor of astronomy at Harvard, director of the Harvard Observatory

from 1921 to 1952, and president of the American Academy of Arts

and Sciences from 1939 to 1944. Shapley was active in organizations on the

political left, and many observers saw him as a man of peace who suggested cooperation

in science and culture with the Soviet Union. The New York intellectuals,

however, viewed Shapley as an irresponsible fellow traveler who unwittingly

aided Stalinist totalitarianism. Courtesy of the Harvard University

Archives.

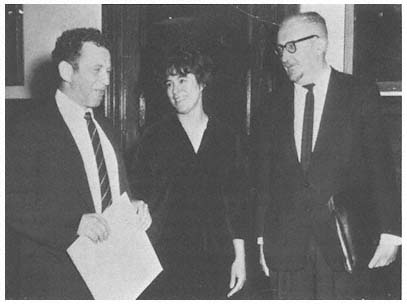

At a gathering in 1947 are, from left to right, Bowden Broadwater (Mary McCarthy's

husband at the time), Lionel Abel (standing), Elizabeth Hardwick (later

associated with the New York Review of Books), Miriam Chiaromonte, Nicola

Chiaromonte (an editor of the Italian Tempo Presente), Mary McCarthy, and

John Berryman; sitting in front are Dwight Macdonald and Kevin McCarthy

(Mary's brother). Courtesy of Vassar College Library.

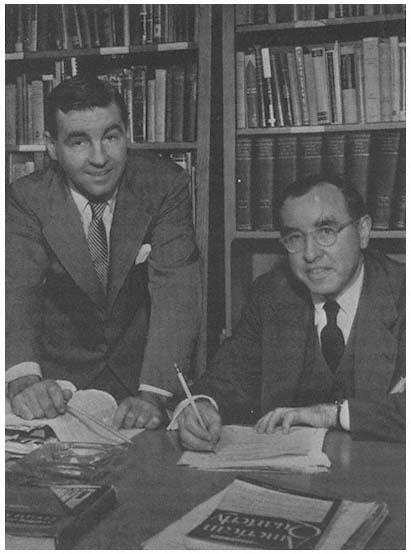

At his office at the University of Chicago, sociologist David Riesman (right) with

Reuel Denney in about 1950. An affiliate of the New York group, Riesman

learned of Nathan Glazer's work by reading Commentary and then collaborated

with Glazer and Denney on The Lonely Crowd, and with Glazer on Faces in the

Crowd. Courtesy of David Riesman.

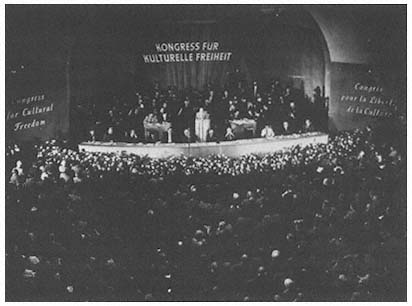

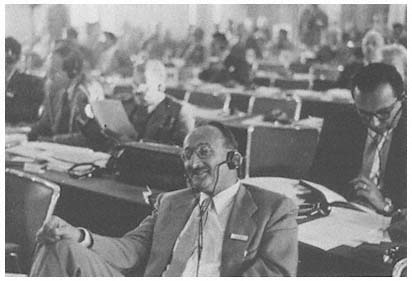

Sidney Hook (at microphone) addressing the opening meeting of the Congress

for Cultural Freedom in Berlin in 1950, standing before the Berlin Philharmonic

Orchestra. At the speakers' table are some of the European associates of the New

York intellectuals: Ignazio Silone (fifth from the left), Arthur Koestler (third

from the right, in a white shirt), and Melvin Lasky (far right). Courtesy of Ernest

B. Hook.

In Austria in 1953, teaching at the Salzburg Seminar in American Studies, are

Daniel Bell (far left) and Seymour Martin Lipset (next left) with students. Courtesy

of Daniel Bell.

While in England on a graduate fellowship at Cambridge University in the early

1950s, Norman Podhoretz (right) visited Irving Kristol at the Encounter office.

Courtesy of Daniel Bell.

French intellectual Raymond Aron (left), whose The Opium of

the Intellectuals was an influential treatise against communist

ideology. Courtesy of Daniel Bell.

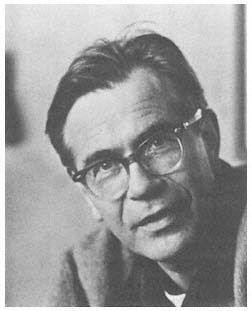

Harold Rosenberg, critic of art and culture for the

New York group's publications, and later for the

New Yorker. Courtesy of the University of Chicago

Press.

Murray Hausknecht in a photo taken by a friend in

1955. Hausknecht, a sociologist who became a contributing

editor of Dissent in 1957, thought that the literature

of ex-Communist repentance encouraged intellectual

conformity and discouraged political radicalism.

Courtesy of Murray Hausknecht.

Sidney Hook, with Seymour Martin Lipset behind him, at the Future of Freedom

conference held by the Congress for Cultural Freedom in Milan in September

1955. It was at this conference that the phrase "end of ideology" began to

gain prominence. Courtesy of Daniel Bell.

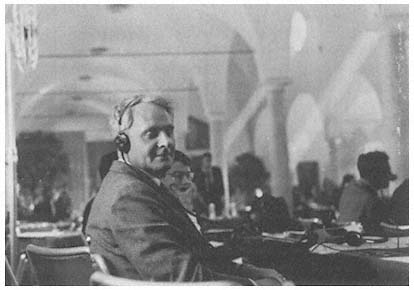

English poet Stephen Spender at the Milan conference. A contributor to The

God That Failed, Spender was from 1953 to 1965 an editor of Encounter, a magazine

published in London by the Congress for Cultural Freedom. Courtesy of

Daniel Bell.

Kitty Galbraith and Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., at the Milan conference. Courtesy

of Daniel Bell.

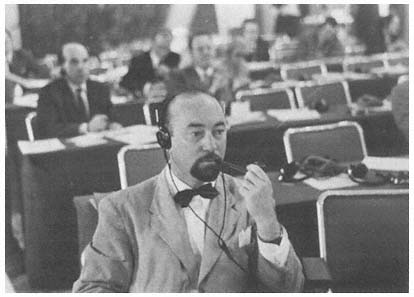

Melvin Lasky at the Milan conference. Lasky was an editor for the New Leader

in the early 1940s, one of the founders of the Congress for Cultural Freedom,

and an editor of Encounter from 1958 until the mid-1960s. Courtesy of Daniel

Bell.

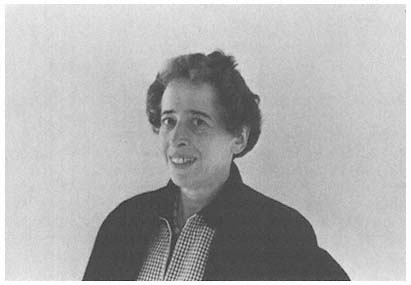

Hannah Arendt, leading theorist on the origins of totalitarianism, at the Milan

conference. Courtesy of Daniel Bell.

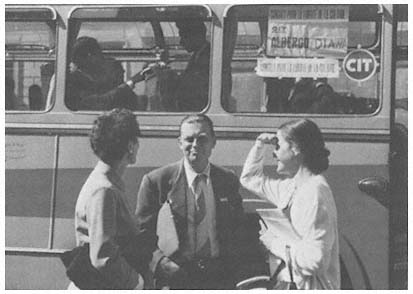

In front of a Congress for Cultural Freedom bus at the Milan conference are

Miriam Chiaromonte, Czeslaw Milosz, and Mary McCarthy. Courtesy of Daniel

Bell.

Daniel Bell in Milan in 1955. Courtesy of Daniel Bell.

Seymour Martin Lipset and Will Herberg at Daniel Bell's summer house in New

Hampshire in 1954. Courtesy of Daniel Bell.

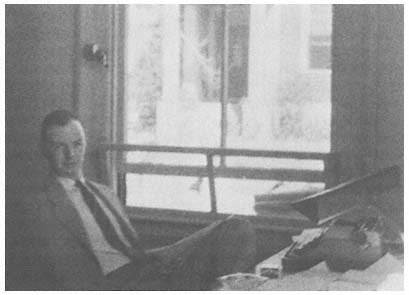

Daniel Bell and Irving Kristol share an umbrella in Rome in the mid-1950s. In

1965 the two founded The Public Interest, which they co-edited. In 1969 a special

issue of the magazine, devoted to an evaluation of student radicalism, was

published as Confrontation. Courtesy of Daniel Bell.

Dennis Wrong, sociologist and contributor to Dissent and Commentary, at work

in his office at Brown University in May 1957. Courtesy of Dennis Wrong.

Sidney Hook reading galleys at home in Brooklyn in

1958 or 1959. Courtesy of Ernest B. Hook.

Edward Shils at work at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences

at Stanford University, in 1958–59. Courtesy of Daniel Bell.

Daniel Bell and Edward Shils at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral

Sciences at Stanford University, in 1958–59. Courtesy of Daniel Bell.

Dennis Wrong in the early

1960s on Central Park West

in New York. Courtesy of

Dennis Wrong.

Dwight Macdonald (right) with Norman and Adele Mailer. Mailer addressed the

Waldorf Conference, was on the editorial board of Dissent and contributed occasional

articles, and marched with Macdonald and Robert Lowell on the Pentagon

on October 21, 1967, a demonstration that became the subject of his Armies of

the Night. One of the founders of the Village Voice, Mailer remained more

sympathetic to the Beats and counterculture than did most other New York intellectuals.

Courtesy of Gloria Macdonald.

Historian Richard Hofstadter was working in

his Columbia University office in Hamilton Hall

on April 23, 1968, when protesters filled the building

and later occupied it. Hofstadter opposed the actions

of the New Left on campuses in the 1960s. Dwight W.

Webb, courtesy of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Dwight Macdonald addressing a crowd of protesters in early 1970, probably at

Hofstra University, where he was teaching for the year. Although Macdonald

disapproved of some of the students' tactics, he was one of the New York intellectuals

who supported the young radicals. Courtesy of Gloria Macdonald.

Dwight Macdonald in his studio in East

Hampton, Long Island. Courtesy of Gloria

Macdonald.

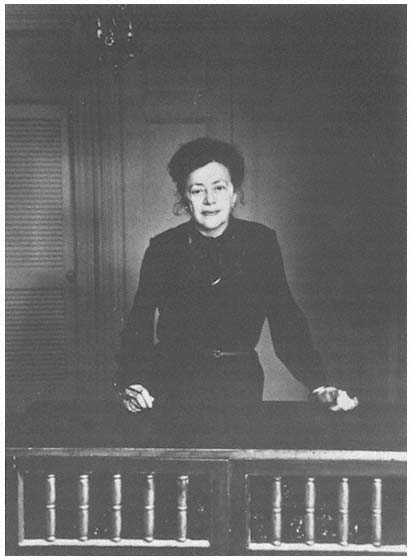

Literary and cultural critic Diana Trilling reviewed books for the Nation in the

1940s, was active in the American Committee for Cultural Freedom in the

1950s, and frequently contributed articles to Commentary and Partisan Review.

Courtesy of Tom Victor and Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, Inc.

Sociologist Nathan Glazer in 1976 in his office

at Harvard University. Glazer was a member

of the editorial staff of Commentary from its

founding in 1945 until 1954. He was teaching

at the University of California at Berkeley during

the height of the student protests, and in the

1960s he wrote essays critical of the excesses of

student radicalism. Courtesy of the Harvard

University News Office.

The member of the New York group most active on the intellectual left after

World War II was literary critic Irving Howe. In addition to attending conferences,

teaching at the City University of New York, and contributing to an array

of periodicals, Howe helped found Dissent in 1954 and served as its most prominent

editor. Courtesy of Irving Howe, The American Newness (Harvard University

Press, 1986).

Midge Decter, executive director of the Committee for the Free World, an organization

that in the 1980s took exception to viewpoints it considered excessively

critical of America or insufficiently vigilant about the dangers of totalitarianism.

Courtesy of Midge Decter.

Sidney Hook giving the Jefferson Lectures at the National Endowment for the

Humanities in 1984. Courtesy of Ernest B. Hook.

Lewis Coser in his office at the

State University of New York at

Stony Brook in 1986. A sociologist

and one of the founders of Dissent,

Coser was one of the New

York intellectuals who maintained

a radical outlook throughout his

career. Courtesy of Joan Powers.

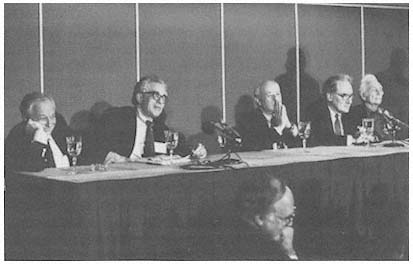

At the Second Thoughts Conference in Washington, D.C., in 1987, disillusioned

former New Leftists expressed repentance, as some of the ex-radicals of the preceding

generation had done in the decade after World War II. Several of the

New York intellectuals attended to encourage or monitor the metamorphosis. At

the dais are, from left to right: Irving Kristol, Nathan Glazer, Norman Podhoretz,

Hilton Kramer, and William Phillips. Courtesy of Rich Lipski and the

Washington Post.