Visions Spread by Contact: The Role of Children

By mid-August 1931, about the same time that the news of Ezkoga began to show its effects throughout Spain, a more local kind of spread was occurring. Returning pilgrims and seers took home the Ezkioga liturgy, emotion, and access to the divine. In adjoining Navarra the same kind of replication spread the visions from village to village. These villages were located in a band between one and two hours' travel from Ezkioga, from which the new shrine was accessible but inconvenient. Seers from the Ezkioga area who worked as servants elsewhere and especially children from elsewhere who had visions at Ezkioga were key vectors in this spread because they could not get to the main site frequently.

The only substantive article on the Ezkioga visions in a Basque republican newspaper, El Liberal of Bilbao, revealed that other visions were taking place in Iturmendi, Bakaiku, and other towns of Navarra south of the Goiherri.[14]

Millán, ELB, 9-10 September 1931.

The Barranca is the broad, high valley of the Arakil river, with high mountains to the north and south. Its inhabitants do not live dispersed in farmhouses, as in most of the Basque Country, but rather clustered in tight villages, as in Alava to the west. But unlike the people of Alava, those of the Barranca speak Basque, and in particular the dialect of their neighbors in Gipuzkoa. As in much of PyreneanSpain and France, the house is the major unit of identity. People belong to a given house and are identified by their house names. The houses are passed on through impartible inheritance, and noninheriting children who marry have to seek their fortunes elsewhere. In 1931 the wealthier households included servants and farm laborers.

From the Barranca two roads wind down into Gipuzkoa: the main highway from Vitoria to San Sebastián, which passes through Altsasu and enters Gipuzkoa at Zegama, and a smaller road from Arbizu through the mountains to Ataun. These roads and countless trails have served traditionally as conduits for frequent contact. Sheep from the mountains of Navarra came down to winter in the milder climes of Gipuzkoa; young women from the Barranca found homes in the convents of the river towns and young men jobs in the factories. The high valley is less than an hour from Ezkioga by car, bus, or truck. But its people—mostly farmers and shepherds, apart from workers in an industrial enclave around Altsasu—were more isolated and poorer, cut off linguistically from the prosperous cities of Estella and Pamplona to the south or Vitoria to the west. They were also devout, and in the first decades of the century the towns received frequent missions, given particularly by the Capuchins in Altsasu.

In the first weeks of the visions the road through Ataun brought constant bus-and truckloads of Navarrese pilgrims to Ezkioga. José Miguel de Barandiarán, the Basque ethnographer from Ataun, remembered them passing in front of his house and once stopping nearby because a girl from Navarra said she was seeing the infant Jesus on a rock in the river.[15]

José Miguel de Barandiarán, Ataun, 9 September 1983, p. 2.

In July Navarrese seers at Ezkioga included a man from Lekunberri (on July 15) and on July 16 a boy from Errotz (near Izurdiaga) and a girl from Arbizu. And when the canon Juan B. Altisent stopped in Arbizu to ask directions, he was told that several children of the village had been lucky enough to see the Virgin.[16]On August 18 in Altisent, CC, 6 September 1931.

In June 1984 I drove to the Barranca to search for memories of what had happened fifty years before. In some towns the atmosphere was tense. The district has been a stronghold of Herri Batasuna, the political party supporting the ETA fighters who from 1968 have kept up a campaign of violence to force Basque separation from Spain. The day before I arrived a demonstration in Etxarri-Aranatz had left one man dead. In Arbizu my guide was Francisco Mendiueta Araña, expert in accordion, harmonica, singing, and whistling. He remembered the truck that came at dusk to take people down to Ezkioga. People were packed into it like upright candles in a box; many were carsick.

The visions in Arbizu started at Ansota, about one and a half kilometers north of the town center, in higher pastureland belonging to the township. The first seers were girls, who were tending cows, but boys had visions too. The visions would start in the late afternoon and go into the night, when the townspeople came and everyone would say the rosary. When I asked Francisco Mendiueta, eight years old at the time of the visions, whether before then anyone had ever

seen witches, he said yes, that with his father at the same place he had seen fireballs on Mount Aitzkorri. The visions at Ansota lasted about a month and then shifted to a new site, still to the north of town, on the road at a place named Baldasoro, where there was a garage and a large ash tree. Finally, they moved to a walnut tree at the cast end of the village. There people prayed with great faith at an altar put up against the Zubaldi house, and one after another the seers would keel back into trance. The visions continued for a couple of months and then petered out. Of the seers Francisco could name four girls and two boys aged seven to twelve, the children of farmers and masons, but he said there were more. A priest native to the village did not believe and said it was witch-stuff and a lie.

It was hard for Francisco and his friends to remember what the seer children saw, apart from the Virgin and the village dead in heaven and hell. What most surprised them was that their pals could perform little miracles. They remember one boy in vision, who somehow knew that Francisco and a friend, out of sight, were rattling a heavy metal ring and called out, "Paco and Blas will go to hell!" And particularly they remembered the seer children, when the visions were over, holding out invisible candy given them by heavenly beings, then eating it. They heard the crinkle of the candies being unwrapped but saw nothing.[17]

Francisco Mendiueta Araña and friends, Arbizu, 15 June 1984.

These stories, like those from Bachicabo, are at once delightful, like homemade fairy tales, and moving. They reveal children and young people who found an opening and accepted an unprecedented gift of authority and usefulness in the village arena. In these backwaters the stakes were less titanic than at Ezkioga, where rural children and adults were eventually negotiating with the gods for the future of the nation and humanity before an audience of thousands. Here the miracles and stakes were often on a smaller scale, involving bread-and-butter questions of daily life among neighbors.

Francisco Mendiueta took me to Torrano (now Dorrao), where we ended up in the large dark house of Felipe Rezano and Felisa Lizarraga. They first went to the visions in other villages and then were intimately involved in those of Dorrao, still believed in them, and talked about them directly, simply, and without complexes. But they said these events were something they had largely forgotten.[18]

Felipe Rezano (b. 1911) and Felisa Lizarraga (b. 1922), Dorrao, 15 June 1984.

The main seer in Dorrao was Inés Igoa, who was about seventeen years old in 1931. Inés would fall into trance during the rosary in her house or outdoors with most of the small village present. She narrated what she was seeing in her trance ("ahora ha salido no-sé-qué"), including, they remember, the Virgin and the Heavenly Father, and she would tell them things "as in a sermon." As for the content of the sermons, they recalled only that she foretold a civil war with the death of many sons. On the whole, they preferred the predictions of Inés to those of the Jehovah's Witnesses.

The only other Dorrao seer was Felisa's brother, José, then twenty years old, but he did not have his visions in a trancelike state, and for Felipe, at least, they

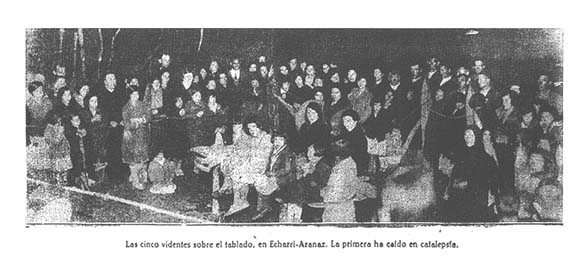

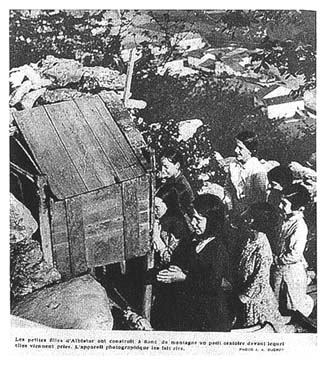

"The five seers on the stage, at Echarri-Aranaz. The first has fallen in catalepsy." Photo by Carlos

Juaristi published in Diario de Navarra, 25 October 1931. Courtesy Hemeroteca Municipal de Madrid

carried less authority. Felipe was one of five youths chosen by the Virgin through Inés as "angels" to help organize the visions. One of their jobs was to cut pine trees, bring them to the village, and set up an altar for the visions. He was a little embarrassed about his being an angel—"How do I know if it was true or not? We said, this cannot be true because we are the worst in the village. What do we know?"

As children Felipe and Felisa both wanted to have visions and went to various sites trying to see. But neither could. At most, they remembered their friends noticing stars that were especially bright. One imagines children, teenagers, and adults peering intently into the heavens at night. Felisa's father and grandfather were great devotees of the Virgin. They took Felisa, who would have been only nine or ten, to Ezkioga three times after the visions in Dorrao had begun.

By a year after her first vision Inés's messages, as reported by Padre Burguera, were quite sophisticated and included references to Freemasonry, Christ the King, the reign of Jesus and Mary in Spain, and a chastisement. Inés also suffered the crucifixion. She was well aware of the government offensive in the fall of 1932.[19]

B 621-623.

At Iturmendi the seers were two boys, aged nine and ten, the sons of farmers. They had their visions on the flat threshing ground called Martinikorena, on the edge of the village, where there were some walnut trees. They too would fall into vision during a rosary at which much of the village was present. In Iturmendi the parish priest forbade an outdoor altar. By identifying some of the village dead in hell these boys caused deep rifts in the town. Not everyone believed their visions, and "some wise guy made a jack-o'-lantern out of a sugar beet with a

Victoriano Juaristi, ca. 1931. Courtesy Carlos Juaristi

candle inside and put it in the cemetery." People remember that the visions lasted two or three months.[20]

Interview with villagers, Iturmendi, 17 June 1984. There were already bandos (factions) in many of these towns, probably based on lineages, and in some places opposing attitudes toward the visions probably formed along these cleavages. See Olabarri, "Documentos." Don Juan Estanga Armendáriz, from Iraneta, was part of a set of local professionals opposed to the visions; the group included his niece, the schoolteacher in Urdiain; the Urdiain parish priest, from Etxarri-Aranatz; and the parish priest of Bakaiku, a village native (Santiago Simón, town secretary of Iturmendi and Bakaiku from 1932 to 1938, Pamplona, 18 June 1984).

At Etxarri-Aranatz a number of seers were having visions by early October. Victoriano Juaristi, president of the Colegio de Médicos of Pamplona, a distinguished psychiatrist and man of letters, was sent there by the bishop of Pamplona when the visions had already built up momentum. On 25 October 1931 he published a critical article in Diario de Navarra . Juaristi's son Carlos, also a doctor, took photographs, and his photos of Etxarri-Aranatz and Unanu, however dark and blurred, are the only, precious, visual evidence I could find of a brief period in the Barranca in the last half of 1931 in which every night children took control.[21]

PV, 18 October 1931, p. 5, named a ten-year-old girl seer at Ezkioga who had already had visions in Etxarri-Aranatz; on Juaristi see Ceballos Vizcarret, Victoriano Juaristi; Blasco Salas, Recuerdos, 159, 203-205; Carlos Juaristi Acevedo, Pamplona, 17 June 1984; Juaristi, DN, 25 October 1931.

Victoriano Juaristi described five or six girls of Etxarri-Aranatz on a low stage separated from the onlookers by barbed wire. During the rosary, "they fell back on their backs one after another, like dolls in a carnival shooting gallery." When Carlos Juaristi fired a magnesium flash, the villagers screamed, apparently thinking the devil was about to appear, and then roughed him up. One man exclaimed, "Coño! Pues eso se avisa" or, approximately, "Shoot! Give us some warning."In Etxarri-Aranatz I spoke with José Maiza Auzmendi, an old believer who had gone on foot to Ezkioga and to other towns in the Barranca to witness the visions. In his town the visions took place on the south side of the highway to Altsasu, before an altar of sorts. After two or three months people gradually stopped going, and the child seers ordered a cross to be placed there. When the parish priest refused to permit a cross, Maiza's father, father-in-law, and uncle

put a cross up in the village cemetery. On the whole, the attitude of the village priests was neutral, he said. The anecdotes townspeople recall confirm the local flavor of the visions. One girl seer relayed news that Serafina, a woman who had died young, was in some difficulty in the afterlife because of an unkept promise. An older woman had been dubbed "Santa Rita" for the saint she was always seeing. And one night the Holy Family appeared with a spirit donkey, and children and adults followed them with lighted candles and lanterns.[22]

José Maiza Auzmendi, Etxarri-Aranatz, 17 June 1984. He also went to Fatima and the more recent apparitions at Monte Umbe near Bilbao. For Holy Family see Francisco Argandoña, "Apariciones de Lizarraga," citing his cousin from Etxarri-Aranatz, Leopoldo Quintana.

The visions in Bakaiku began by the river and the train tracks, where there were poplar trees. According to El Liberal this was in mid-August.

At Bacaicoa the infant Jesus appeared and spoke to a villager who made doughnuts [churros ]; but the man could not reveal what he heard as it was a secret. Nevertheless he says he has it all written down in a sealed envelope. The doughnut man made a penitential promise not to speak at all and to go for several days to the apparition site barefoot and with his head hanging down.[23]

Millán, ELB, 9-10 September 1931.

The writer observed that children were usually playing at the place the infant Jesus appeared, and he commented cynically that the doughnut business was doing very well. He said the Virgin was seen in "another nearby village" walking in a poplar grove along the banks of the river.

The visions were still in full force on 17 November 1931 when Padre Burguera arrived. He was particularly impressed with María Celaya, who kept a notebook entitled "Las Apariciones de Bacaicoa," starting with her first vision on October 16. Burguera accompanied her to Ezkioga and observed her again in her home village. In all he named eleven seers there: a woman aged 58; girls aged 17, 12, 11, 11, 10, 9, 9, 8, and 5; and a boy aged 8. These children included two sets of siblings.[24]

B 663-664. Burguera used Celaya's notebook when preparing his book; the notebook is probably with his papers in Sueca. B II 628, 636-637.

According to Burguera the visions had begun with two eight-year-old children, a boy and a girl, playing by the river. There they met a strange child and gathered mulberries with him. The child told them that he was named Jesus, his mother was named Mary, and they should go to Ezkioga where his mother was waiting for them. They noticed that his hands, unlike theirs, did not become stained by the berries and that he walked on the water of the river. A wealthy female relative duly took the children by car to Ezkioga, about thirty kilometers away, and there they saw the Virgin, who confirmed their vision by the river and gave them secrets. More children went to the river site and had visions of Mary and the child Jesus, whom they referred to as the Infant Jesus of Prague, after the Carmelite devotion popular in the zone.[25]

Child sodalities were founded to the Infant Jesus of Prague in Vitoria in 1905, San Sebastián and Pamplona in 1908, Villafranca in 1910, Elizondo in 1917, and a number of villages in Navarra in 1922 and 1923 (Doroteo, Historia prodigiosa, 168-229). Arte Cristiana of Olot, a major factory for religious images, started making the Infant Jesus of Prague in 1905 (company records).

At Bakaiku the visions received a boost from some of the village elite, including the wife of the civil engineer and politician Wenceslao Goizueta, and the schoolteacher, Francisca Setoáin. When Burguera went to the school, eight children went into trance for him. He referred to the teacher as a "tireless

apostle." Perhaps in the vision messages there is an echo of her interest, for the first two seers said that the Virgin told them the visions were for the people of Spain, "who honored God so much and now officially dishonor him." Messages like this should alert us to the bias of oral testimony based on memory. No doubt local people are much more likely to retain anecdotes anchored in kinship and place and less likely to remember messages of political or theological importance. By contrast, the written reports of ideologues like Burguera would likely leave out the more local meanings. These seers were speaking simultaneously to both levels.[26]

B II 634-637. The teacher was the village representative for the children's religious magazine, La Obra Máxima (January 1931, p. vi).

The seers also ran into opposition, especially from some of the men of the village, which María Celaya described in her notebook. For a while their visions attracted spectators from a wide radius, but as more villages had their own seers, with messages more specific to their neighbors and problems, fewer people went to Bakaiku.[27]

B 664.

People I talked to remembered the Lizarraga visions beginning after those of Bakaiku, Lizarraga-ergoien was on an excitement route, the road from Lezaun and the Estella region of Navarra, which sent many busloads of pilgrims to Ezkioga in the months of July and August 1931. Such routes became corridors of enthusiasm. Francisco Argandoña, who as a boy went from Lezaun, said that after an outdoor rosary all the children, agreeing with whoever spoke first, saw the saints arrive from over the mountains. The night he was there, the procession began with Saint Joseph, centered on the infant Jesus, and ended with Saint Adrian on a white horse. The next morning he was taken to a girl who said she played with the infant Jesus whenever she wanted to and who handed him an invisible baby Jesus so small it could fit in the palm of her hand.[28]

Francisco Argandoña (b. 1924), "Apariciones de Lizarraga," 4-5.

By late November, as at Ezkioga, the visions had taken a turn for the macabre and apocalyptic. Burguera saw twelve seers from seven households: a woman aged 21; girls aged 12, 12, 11, 11, 10, 9, and 4; and four boys, all of them younger brothers of girl seers, aged 13, 8, 7, and 6. Another observer put the number of seers at more than thirty and wrote:

The seers seemed to be petrified, first supplicating with their eyes upward and their hands joined, then horrified by what they were seeing in their terrible and tragic vision, sometimes giving screams of fear for the catastrophe that they saw coming in the war and other chastisements that would occur in the world.

As in the other villages, the seers had an altar on the threshing ground and an enclosure for their visions, and adults brought chairs and benches to sit on. Some visions were right out in the road. One boy had a vision on top of a delivery van; when it drove off, the boy fell off but was unhurt.[29]

B II 628; quote from Pedro Balda, the Iraneta town secretary, to Guerau de Arellano, 9 November 1937, AC 264; Burguera (B 662) mentions a redondel in which seers prayed; for delivery van, Pedro Balda, Alkotz, 8 April 1983, pp. 8-9.

The Lizarraga seers said the devil attacked them. According to the psychiatrist Victoriano Juaristi, adult seers saw Saint Michael struggling and tried to help him

by hitting the devil with a candlestick. Seers said that on the highway the devil tried to get them to throw off the many rosaries, medals, and crucifixes they were wearing for the divine to bless. Burguera himself at least twice gave his rosary to the seers to hold when they were seeing the infant Jesus. A town official eventually forbade the visions. One household with four child seers resisted and the matter ended in a lawsuit. This family was still holding visions at home in the fall of 1933.

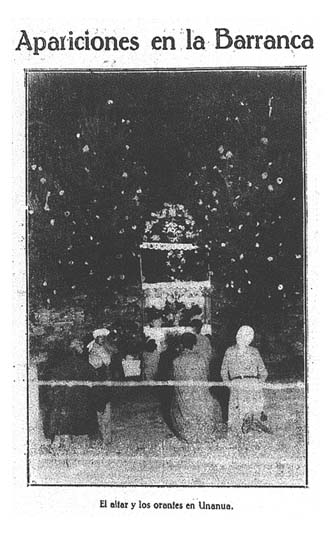

From Lizarraga the visions spread to adjacent Dorrao and then down the road to Unanu. While people in Unanu refused to speak of the visions in 1984, they were open with Juaristi in October 1931. He left a striking account and a valuable photograph that shows an altar decked with pine boughs like that of Dorrao.

We are at the foot of the pointed peak of San Donato, which looks like a gigantic altar. And above the green and black floor of the valley, next to the cliff base, there is a circle of weak, reddish light, which has drawn to it about fifty persons who are kneeling. In the middle of the circle there are four children and an equal number of women, kneeling as well, facing the base of the cliff, whence the light comes. An eldery man, thin and erect, recites with a dry, firm, clear voice a litany that the women answer; then he gets up and leads them in a hymn.

The light is hidden in the boughs of some high bushes, formed into a strange kind of multicolored oven shape; it seems to be some kind of altar. Suddenly, one of the girls opens her arms out like a cross, throws her head back, arcs her body, and goes stiff, the moonlight bathing her pale face, her eyes, as if dead, staring unblinking into the infinite. Immediately a boy, younger, and another boy fall into a similar cataleptic state, and two women with white coifs hold them. The prayers continue without interruption.

We are filled with awe, spectators in the dark at a rite like that which must have been the moon cult of the ancient Vascones.

The children come back to life, first the older girl, then the others. The girl says she has seen the Virgin with a blue mantle and a silver crown, barefoot and with golden rays in her hands, and the Virgin told her … that we should go and have supper! The spell is broken and we mix with the spectators, who get up. Some friendly words in Basque serve to relieve their fear and distrust, and the children (the youngest is barely four years old) answer our questions as any children would, their mothers filling out their replies.

The girl is lively and communicative, and she is aware of the authority she wields among her kind. Always "by order of the Virgin," she says how much they have to pray, and who has to do it; she orders that the Daughters of Mary spend Sunday making paper flowers and that people come in the evening. She recounts struggles between Saint Michael, dressed in gold with his flashing sword, and a blackened, horned devil. To a request for more details, she says that the devil wears a black jacket, goes without pants,

"The altar and those praying in Unanua," October 1931.

Photo by Carlos Juaristi published in Diario de Navarra,

25 October 1931. Courtesy Hemeroteca Municipal de Madrid

and uses a staff. She describes macabre processions, identifying the dead of the town as they go past. Behind the dead walks a young idiot girl who used to work with a hatchet; she carries it in the funeral procession as well and limps because she wounded herself with it trying to open the gates of heaven. She blesses pacharanes , or bilberries, so that the sick can eat them and get well.

Time and again she falls into a new fit, followed by the other children. Then we are able to observe them as doctors and notice all the signs of a neurosis.

The parish priest, whom we visit, is an educated man with common sense who gives us interesting information and is happy that we doctors

have intervened to set right something he always thought was pathological and harmful to true faith. But his counsel and his sermons along these lines have fallen on deaf ears. The seer girl has "her" church; she wants nothing to do with the "other," or with the priest. And the mothers consider themselves happy for the "celestial" favor that their children have received.[30]

B II 635 n. 59, 632 n. 55; B 662-663; Juaristi, DN, 25 October 1931.

Juaristi presented visions as neurotic and pathological. In Pamplona he was something of a liberal, a black sheep who did not attend church and who the bishop knew in advance would not sympathize with the phenomena. In his article Juaristi pointed out that waves of hysterical behavior were common in all times and that in the past the seers would have been accused of witchcraft. Yet his observations do not appear to have been skewed, for the setting and the social dynamic he described are similar to what we know about in other villages.

Like José Antonio Laburu's lectures, Juaristi's article bore the authority of science. Pedro Balda, the Iraneta town secretary and scribe for another seer, described for a friend its impact on the Barranca:

Finally a doctor declared that it was not ecstacy but instead a sickness called "neurosis," and that it had occurred in a similar form in Germany before the European war. It did not take much for people to lose the fervor of the first days, and many who were believers in the supernatural [aspect of the visions] became enemies of the mysterious phenomena…. If they fed them well, some said, the neurosis would disappear immediately. Others said that with a good beating every day, they would stop having visions at once. Most said that it was a "farce." That is why most of the believers withdrew from attending what had attracted the attention of so many thousands.[31]

Balda to Gerau de Arellano, [Iraneta], 9 November 1937, AC 264.

There were visions in two other Barranca villages, Lakuntza and Iraneta. In Lakuntza a seventeen-year-old Bakaiku youth who worked in the lock factory told people about the visions in Bakaiku and led them down the railroad line to the regular site there. When he got there, he claimed to see the Virgin in the poplars by the river.

Two boys, sons of farmers, claimed to see the Virgin in Lakuntza in an oak tree near the railroad tracks, on the road to the mountain, and on a door-latch in the village. According to one witness, the people of the town attended for a while, but on one night when the boys announced a vision at two in the morning in the pouring rain, an elderly man announced that he was going to stay home, dry and in bed; that seemed to put things in perspective and no one went.

Lakuntza seems to have turned against the visions rather quickly, perhaps because of its factory workers but in part because of Blas Alegría, a priest born in the village. He was outspoken against the visions, maintaining that "the Virgin is in heaven, and she does not leave it." The man I spoke to most in Lakuntza had another reason for not believing. He was twenty-nine in 1931 and worked

in the factory with the seer from Bakaiku. He kept pressing the boy, who finally told him, "Well, when a lot of people go, I say that I see because they pay me; but when just a few people go, I don't see and I go home."[32]

Emilio Andueza (b. 1902), Lakuntza, 15 June 1984.

Six kilometers east of Lakuntza lies Iraneta. This is the Barranca town in which the visions lasted the longest, primarily because of the special alliance between a seer, Luis Irurzun, and the town secretary, Pedro Balda. I talked to Balda in the old-age home in Alkotz and to Irurzun in San Sebastián. Balda, born in 1894 in Iraneta, where there were about sixty houses, was the eldest of seven siblings in a poor family without land. His father was a pastry and chocolate maker and his mother took in laundry, made bread in people's houses, and did agricultural labor. Before her marriage, Balda's mother cleaned and decorated the church for a parish priest who belonged to Luis Irurzun's "house." The priest took an interest in young Pedro Balda, made him an altar boy, and taught him to sing the mass in Latin. Starting when he was ten years old Pedro worked as a farm laborer, and he barely learned to read and write until his military service, during which he studied and rose to be a sergeant. In 1923 he became the town secretary.

Balda took a keen interest in all matters religious and went to Ezkioga on 18 July 1931, one of the big days. Then, when the visions started in the Barranca, he visited several sites, particularly Lizarraga. His self-education, rare in a town secretary, gave him perhaps a more independent frame of mind and left him closer to the people. Similarly, his informal training in the church, like that of many sextons, demystified for him the opinions of the clergy. He paid little heed to the first seer in Iraneta, a girl about eight years old named Inocencia who saw the Virgin in late September and told people to pray the rosary. Others began to have visions at the outdoor site, including a disbelieving adult relative of the girl, María Arratibel, who saw Saint Michael the Archangel. On September 29 another woman, Juana Huarte, aged thirty, also saw the Virgin and Saint Michael, whose shrine on Mount Aralar dominates the Barranca.[33]

B 650 gives the Huarte vision as Iraneta's first, but Irurzun (San Sebastián, 5 April 1983, p. 2) and Balda (Alkotz, 8 April 1983, pp. 17-18) were firm that Inocencia started everything. I base my account of Iraneta on these interviews in addition to the other citations.

Luis Irurzun, a youth aged eighteen, from a prosperous house, was not one of the persons who went to the visions. He liked to dance and play the accordion, which stricter members of the community considered "the devil's bellows." On October 12, when the Ezkioga visions were attracting large crowds and the Cortes was debating the separation of church and state, Luis was on his way with seven or eight youths to the fiestas of Lekunberri to see traveling puppeteers. They stopped briefly at the vision site in a field by the road, where a rosary was getting started. Luis was smoking, and a woman named Petra pulled the cigarette from his mouth, saying, "When you pray, do it right." Luis started to smoke again and suddenly lost consciousness.

Balda had been at the visions in Lizarraga that afternoon, and he claimed to me that the seer Nicasia Lacunza, aged twenty-one, had told him that Luis would have visions. On his return Balda heard what happened, and he found Luis at

home in a stupor. The next day Luis had a vision of the Virgin with twelve stars around her and thereafter at three in the afternoon he had daily visions. As a friend and favored client of Luis's house, Balda was affected profoundly.

There were other new seers, including a contemporary of Luis's.[34]

The other youth was Francisco Diego Jamós, B 650.

Balda remembered the two marching in unison as soldiers of the archangel. I wondered how much Balda himself, as a significant member of the audience and the only one keeping a record, helped to elicit bellicose visions. He had been reprimanded by the governor of Navarra because at the first town council meeting after the Republic was declared he had said, "We are in mourning." When recalling the visions, he emphasized the predictions of war.Luis had a flair unmatched in the Barranca. He was capable of delivering sermons while in trance for up to two hours in a voice that could be heard across the fields. In spite of other new seers, he was indisputably the central figure. He claimed not only to know future events but also to read people's consciences and thereby provoke conversions. As he put it to me, "I had a grace to be able to look at someone and to know what was wrong with him—sickness and sins and everything."

Balda's family frequently drove Luis to Ezkioga, and his visions there and in Pamplona, Bilbao, and throughout Gipuzkoa spread his fame. Joaquín Sicart sold his photograph. Carmen Medina and Juan Bautista Ayerbe befriended him, and for a time Padre Burguera was his spiritual director. Luis was friendly with several seers, including Patxi, whom Carmen Medina took to Iraneta.

According to Luis, about a month after his visions started, in mid-November 1931, all the seers received orders from the governor of Navarra to submit to a medical examination. Then, at the height of his popularity, Luis went to Juaristi's clinic in Pamplona. In 1983 he told me that after twenty-five days the doctor confessed that medical science could not help and asked for his intercession with the Virgin. Luis also said that in Pamplona his companion from Iraneta, an atheist, tried to take him to a brothel, but when he saw the women inside he fell down the stairs unconscious.

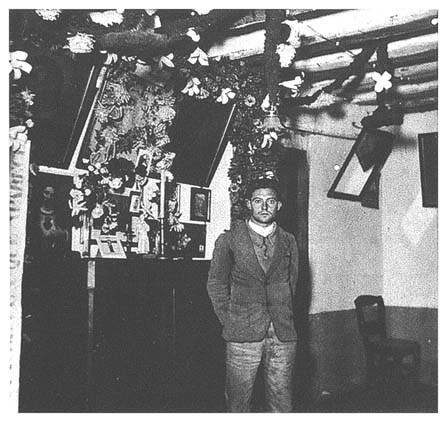

Luis's visions continued on his return. He told me that at that point every day there were eight or ten buses of spectators, some of them from Pamplona, as well as those who came on foot. His fame increased because of a kind of miracle announced by Saint Michael in one of Luis's visions three days in advance. During the Litany on 8 December 1931 in the church packed with spectators, Luis's hands and shirt were suddenly covered with blood. Luis announced solemnly that the blood was "the tears of the Virgin." Marcelo Garciarena, the parish priest, who had no truck with the visions, snapped, "Shut up, fool." Still apparently in vision, Luis announced that the Virgin wanted him carried home, with the Salve to be sung along the way. As they carried him singing, Balda remembers that a woman came out of her house, furious, and said, "Throw him on the fire. That'll

Luis Irurzun at home, late 1931 or early 1932; on the ribbon at the left are the words "Blessed

is She who appears" and on the altar is a card of a Rafols crucifix. Photo by Carlos Juaristi

wake him up!" Balda saved the shirt as a relic and eventually Padre Burguera collected it.[35]

B 651-652.

Most town councils in the Barranca had opposed the Republic in April 1931. By the end of 1932, however, many of them had town councillors who defined themselves as republicans.[36]

Virto, Elecciones, 157-214. For politics in these towns also Ferrer Muñoz, Elecciones y partidos, 92, 98, 161-163, 507-508.

The modus vivendi with the Republic worked against the visions. The church also came down against the visions, and most people in Iraneta sided with the parish priest. Some people found incongruities in the content of the visions. At first most spectators were from Iraneta and Ihabar, and one Iraneta woman stopped believing when in vision Luis said, "The Virgin has said that the girls from Ihabar should sing a hymn." The Iraneta woman saw no reason why the Virgin should single out the girls from Ihabar.[37]Maritxu Güller, San Sebastián, 4 February 1986, p. 10.

Nevertheless, Luis's visions survived the longest in public of all those in Navarra. In March 1932 Governor Bandrés called him to Pamplona and told him he would have no more visions, which earned the seer a headline and, doubtless, more followers. Irurzun told me he assured the governor that he was having visions at 3 P.M. every day and offered to return at that time, but the governor declined (in panic, Luis thought). He said the governor threatened him with jail but in fact did nothing, and Luis went home. At this point the Navarrese were still going to Ezkioga itself, some in buses from Pamplona and others on foot from the Barranca, praying out loud as they went. When the governor ordered the last outdoor vision stages and altars in the province dismantled, Iraneta was one of the holdouts. In October 1932 Luis was still having visions, and seers and their families from other places went to see and have visions with him. An occasional bus brought spectators from the city.[38]

"A un vecino de Irañeta se le prohibe ver visiones," PV, 27 March 1932, p. 2; advertisements for bus trips on Good Friday, 25 March 1932, in VN, 24 March, p. 2; for Barranca, Andueza, LC, 11 March 1931.

In March 1933 Bishop Muniz y Pablos of Pamplona sent a circular to the priests of the valleys of Arakil and Burunda that forbade attendance at the visions and denied that they had any supernatural character.[39]

Muniz y Pablos circular of March 23. B 267-268, 365-369. Díaz Sintes, "Tomás Muniz de Pablos," makes no mention of the visions or the bishop's attitude.

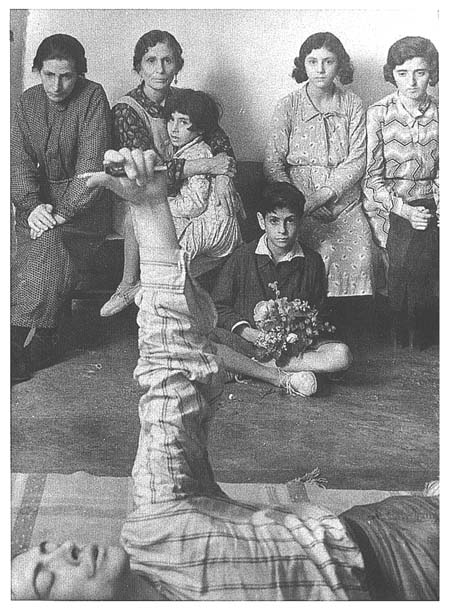

José Maiza remembered being mocked in Lakuntza and Arbizu when he would walk to Iraneta from Etxarri-Aranatz. And the two families who were the last to go from Arbizu had to do so secretly, so much had public opinion there changed.In May 1933 Raymond de Rigné brought J. A. Ducrot, a journalist from the French photo magazine VU , to Iraneta. By then Luis gave vision sermons in his house. Ducrot saw Luis fall backward "as if hit on the chin," for a while maintain a praying posture, eyes closed, but then begin to preach like a seasoned orator. "His voice, resonant, swells, takes on a poignant tone. Little by little he gets more deeply involved, and he lives what he describes." Luis then acted out a battle between Saint Michael and the devil, "like a tempest that shook the house." It ended as suddenly as it began. Luis answered Ducrot's questions, and from Luis's instructions the reporter made a sketch of the devil and Saint Michael. Luis told him that in the great chastisement "the sword of Saint Michael would kill people at the rate of two million every five minutes, and the earth would be almost depopulated in several hours." Luis's story constituted most of the third and concluding installment of Ducrot's report on Ezkioga. The cover showed Luis just as he had fallen to the floor, held by Pedro Balda and two other young men.[40]

Ducrot, VU, 30 August 1933.

Five months later there were only twenty-two spectators, and in May 1934 people attended from only four households.[41]

Pedro Balda (distributed by J. B. Ayerbe), "Visión del joven labrador Luis Irurzun ... 12 de octubre, 1933 a las 17:15," AC 233. By then Balda had recorded over four hundred vision sermons. [Pedro Balda to Juan Bautista Ayerbe], "Dos cartas interesantes de Irañeta," 18 May 1934, AC 246.

Attendance was even sparser when Maritxu Erlanz arrived as the new schoolmistress, probably in 1935, and Pedro Balda took her to a secret session. By that time it was considered sinful to attend and Maritxu had to be careful not to be seen. The visions were no longer held daily. Only five men were present: three from Iraneta, one from Lakuntza, and the vision promoter Tomás Imaz. They said the rosary and the Litany and then Luis gave a cry in Basque and fell down. He was propped up with a pillow, his face began to sweat, and he delivered a long, disjointed, sermonlike speech in

Luis Irurzun on floor of his house, ca. 1933

Spanish. He told of the call-up of conscripts, of a coming war, and of bodies in roadside ditches, with an admixture of biblical material. The highlight for Maritxu was that he seemed briefly to levitate, but her overall impression was a certain lack of spontaneity, a feeling that the vision was prepared, and she did not return. She told me that comparing Pedro Balda's version of Luis's sermon with what Luis actually said, it seemed that Balda was dressing up the language and adding things. Balda confirmed to me that in his enthusiasm he had interpolated material in the texts and that for that reason they should not be published.[42]

Maritxu Güller (maiden name, Erlanz), San Sebastián, 4 February 1986, pp. 1-6. "There were many things which I later realized that I added myself": Pedro Balda, Alkotz, 7 June 1984, p. 8.

Balda's interpolations raise the difficult question of how to reconstruct what any of these visionaries said or what they wanted to say. Almost inevitably we are restricted to describing the multiple mirrors—the hopes and anxieties of the listeners—that distorted the messages. For instance, Balda included in his wide correspondence poems of his own, such as the one he vigorously recited to me at age ninety, composed in 1933 or 1934. I translate the last quatrains:

The right and the left laugh

at the Holy Apparition.

If they keep it up

they will be sent to hell .

What sorrow! What bitterness

will some day be felt

when God casts his sword

and shakes the world .

"That day is not far off"

the seers are saying,

and at the divine warnings

the people are laughing .

The laughter will cease

when the great fright comes,

and all the happiness

will change into tears .

For our enemies

that day will be horrible;

it will be a day of fulfillment

for the sons of Mary .

Hear the voice of Christ

who will come to reign soon,

for if Christ did not come

the world would be ruined .[43]Variants of this poem, entitled "Voces en el desierto" or "Avisos de la Santísima Virgen de Ezkioga," are on four of J. B. Ayerbe's circulars. The only dated one is 5 January 1934, AC 235, 235 a, b, c.

Derechas e izquierdas se ríen

de la Santa Aparición,

si persisten en su empeño

tendrán la condenación.

Qué tristezas! ¡Qué amarguras!

algún día se han de ver

cuando Dios lance la espada

que al mundo haga mover.

"El día no está lejano"

van diciendo los videntes

y de los avisos divinos

se van riendo las gentes.

Las risas se acabarán

cuando llegue el gran espanto

y todas las alegrías

se convirtirán en llanto.

Para nuestros enemigos

será espantoso ese día;

será día de ventura

para los hijos de María.

Escuchad la voz de Cristo

que pronto vendrá a reinar

que si Cristo no viniera,

el mundo se iba a arruinar.

Although Pedro Balda refined the written messages, it is clear that Luis not only took people aside to tell them (whether correctly or not) their private sins

but also announced that certain people, like the male schoolteacher, would die. Pedro Balda wrote the vicar general Justo de Echeguren in Vitoria and over a back fence informed a priest in Iraneta that seers had foreseen their untimely end. These announcements were not well received, and many villagers came to look at Luis askance.

For what Luis and others were doing was risky. People knew they had visions of and struggles with the devil. If their predictions turned out to be accurate, the question could be posed: Did they act or speak with the devil's help? The fear of malevolence that led to accusations of witchcraft three hundred years earlier was still alive in the twentieth century. Rural folk were alert to the power of curses and of quasi-religious rituals to maim and kill. Once the church denounced the visions, not a few people, like the parish priest of Arbizu, judged them to be sorcery and shunned the seers. If the seers were wrong in their predictions, they could be labeled charlatans. The psychiatrist Juaristi opened yet another line of explanation: mental illness. In the long run his diagnosis may have helped to relieve seers of opprobrium, but in the short run it tended to isolate them, for Juaristi described the illness as contagious.[44]

For Luis's predictions of deaths: Maritxu Güller, 4 February 1986, p. 12, and Pedro Balda, Alkotz, 7 June 1984, pp. 2, 14. For varieties of malevolent power: Barandiarán, "En Ataun," AEF, 1923, p. 114; Barandiarán, "En Orozco," AEF, 1923, p. 5; in Zegama, Gorrochategui and Aracama, AEF, 1923, p. 107. Evarista Galdós claimed to predict the dates of death of the sister of a believer, a priest, and a boy from Azkoitia (B 715, 719, 721). She thought of this as a kind of holy knowledge, like that of nuns who announced the date and time of their own deaths; but some people I talked to saw it as a bad kind of knowledge. Gábor Klaniczáy discusses the danger of charisma for women in "Ambivalence of Charisma."

There were other mini-Ezkiogas in the near vicinity. One sequence of visions took place in a pair of villages to the east of the Barranca, Izurdiaga and Irurtzun. According to one source, the Izurdiaga visions began on 11 October 1931, that is, at the height of those in the Barranca. At the beginning of December a priest, Marcelo Celigueta, reported to the vicar general of Pamplona on behalf of the pastor of Izurdiaga, his brother Patricio. For more than a month there had been three seers in Izurdiaga, two girls aged seven and ten and a boy aged eleven. Watched by about thirty children and ten adults, they were having visions every day during prayers to the Blessed Sacrament. The schoolmistress led these prayers in the church prior to the evening rosary. Perhaps because one of the girls was his niece, the parish priest was sympathetic.[45]

Boniface, Genèse d'Ezkioga. ADP Fondo Parroquias: Izurdiaga. Marcelo Celigueta. presbítero, al Provisor y Vicario General, Pamplona, 1 folio, 2 sides, manuscript, dated "Aibar, Fiesta de San Xavier [3 December] de 1931." This folio has holes punched in it and may have come loose from a binder relating to the 1931 events. It was the only item relating to the 1931 visions in the parish correspondence files for all villages where I knew there had been visions.

The youngest girl had been to Ezkioga. There the Virgin had said that she would make herself visible whenever the girl prayed a Hail Mary. Then the three children had visions on a hillside in Irurtzun for several days, attracting a thousand spectators. The littlest girl said the Virgin had given her a picture of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, which she gave to her schoolmistress to keep. The Virgin said there that those who kissed the little girl's hand or received the blessing of the other girl could receive Communion the following day. Like seers of the Barranca and at Ezkioga, the children saw an apocalyptic battle between devils and Saint Michael. There had been Irurtzun children who had had visions as well, but their parents had treated them harshly. The Izurdiaga seers learned from the Virgin that those parents would be punished. By December the Irurtzun outdoor visions had ended.

The sessions in the Izurdiaga church were similar to those in the rest of the Barranca. When the children first began their prayers, they would fall into

"ecstasies" (Marcelo Celigueta's word) lasting up to an hour. They would offer flowers to the Virgin and at the end of the session distribute the flowers by name to the persons that the Virgin indicated, even if they did not know them. They did so on their knees and without removing their gaze from the Virgin.

Marcelo described other aspects of the visions as well.

Other times, after having put on behalf of the Virgin much fear into some child who was not praying or who was distracted, they would mark out with the petals of the flowers a kind of cloud that when they returned to their normal senses they explain is the perimeter of the aura, like that of the sun, around the Virgin; and within this they mark out another circle, like that which a person occupies when standing, and they do not let anyone go there or step there during the apparition.

They are given rosaries and medals so that at the end, when the children say the word "Bendición," the Virgin blesses them several times, or perhaps blesses several people in particular. And as the Virgin does it, the children once or several times make a perfect cross in blessing. Normally the rosaries in question are already blessed by a priest. One day they gave a rosary like the others to the girl when she was in ecstasy, and she rejected only this one. A priest, who had the authority to do so, made the sign of the cross and blessed it; and they gave it to the girl and she was not sure whether to accept it. She finally took it, and without waking up from her ecstatic sleep or whatever, she gave it by name to the girl it belonged to. After the session they asked her, "Why did you not accept the rosary the first time and then accept it later?" "Because the Virgin did not want it because it was not blessed." "And why later?" "Because it had been blessed." "Then who blessed it?" "I don't know, but the Virgin said it was now blessed."

During the ecstasy, their eyes are always fixed on something; their retinas are motionless in spite of the sharp glare of a light put before them, and when their bodies are pricked they feel nothing. The first days they appeared to be frightened and wept because the Sorrowing Virgin wept, and later they are seen smiling because she does not weep. You can see them speaking to the Virgin and answering. A person close to them can follow the conversation. Then they say something like, "Virgen Santísima, Save Spain," and after finishing, they say that the Virgin will save Spain.

Asked on someone's request if certain persons have been saved, of almost all they say yes—of one they said that he needed two Rosaries for his soul. A woman asked that the Virgin give the name of one of the souls that was saved . "That question should not be asked; [the woman] knows the name." Another time they asked where three (deceased) persons were, and the children understood, as with the previous woman. The response, that "the ones who are dead are in heaven, but do not ask about the other one because you know he is alive and in what village he lives," was true.

Celigueta also wrote that the children in vision used flower petals to make on the altar a perfect design of a monstrance and a decorative host with a cross

in the center. And he said that "most persons present noted an intense fragrance of lily [azucena ]." When asked, the children said it was the scent of the Virgin. Other days they played on their knees with the infant Jesus and their flowers. Sometimes the devil wanted to take the flowers away. "Not for you, ugly; these are for the Virgin," and they would chase him away with the sign of the cross, making fun of him.

Marcelo Celigueta was dubious about much of what he described, which he called "the dark side of the picture." He singled out the time the children claimed to have gone to heaven.

One day they wanted to go to heaven with the Virgin, and helped by those present, they got up on the altar, respecting the sepulcher, and there they stood forming a tight group, kissing each other. They were asked how they had done this, even though they were in ecstasy. "Because the Virgin had taken them to heaven"—where they said they had been, and the little one added, "I was so happy in heaven that I did not want to come down!"

Many aspects impressed Celigueta: the way the children in trance seemed to know names and persons and who was dead and who still alive, the physiological aspects of their states, the artistic beauty and exactness of their floral decorations (these especially impressed Balda when he visited), and their consistency—in spite of frequent and separate questioning they did not seem to contradict themselves or one another.

Again evident in this report is the immediate political relevance of the visions. At Izurdiaga the Virgin told the children that all persons who entered the church should dip their hands in the holy water and repeat:

Sacred Heart of Jesus, Save Spain

Virgin of El Pilar, Save Spain.

Sacred Heart of Jesus, in you I trust.

Virgin of El Pilar, in you I trust.

Both Juaristi and Bishop Muniz y Pablos of Pamplona spoke of the political moment as a major factor contributing both to the visions and belief in them. In his 1933 circular the bishop wrote,

Historically, in times of serious social strife like the one we are experiencing, it is common that these seers appear and multiply, and there are usually two causes attributed to this: the first is the anguish and disorientation normal in simple souls who, not finding an easy solution either in the human order or in the ordinary paths of divine providence, aspire and believe to find it in the supernatural, in God acting directly on society and not through intermediate causes; the second cause is that the spirit of evil himself suggests these aspirations, whether so that people will relax in the hope of extraordinary solutions and not work diligently to solve things on

their own; or to stifle the faith, as they stifle it in those persons who believe in these visions and prophecies and then see that they do not come true.[46]

Tomás Muniz y Pablos, "A los Rvdos. Sres. párrocos y sacerdotes de los valles de Araquil y Burundi," 23 de Marzo de 1933 (in B 366-367).

In Izurdiaga, as in Bakaiku, the schoolteacher encouraged the visions. Pedro Balda remembered that she tried to get reports into newspapers and even spoke to the bishop. She seems to have relayed to her charges adult issues. Six months before the visions began, she got the boys and girls to write the director of a mission magazine. Their letters convey the mix of adult and child-like elements which made all the children's visions possible and attractive.

Izurdiaga, 31 March 1931

As soon as our new schoolmistress told us how to rescue the soul of an unbeliever, we gladly deprived ourselves of treats in order to contribute to save souls. We drew lots, and it fell to me to send you this letter, and I want [the pagan child] to be called Francisco Javier. Later we will send you used stamps. I ask for your blessing for all the boys of this school, without forgetting our schoolmistress, and kiss your holy scapular in the name of all of us.

Francisco Satrústegui

Izurdiaga, 6 May 1931

We, the girls of this school, who will not let the boys outdo us, have saved by not buying sweets the 10 pesetas needed to baptize a little Chinese girl, and we send them very gladly. Since we collected the money in the month of May, we wish to offer a rose to the Virgin to make very holy, and we want her to bear the name Rosa María, and Soledad for that is the name of the girl to whom it fell to write the present letter. On Ascension Day we will receive into our hearts for the first time the Baby Jesus, and we will beseech him to make us missionaries so we can save many souls. Pray, Father, so we will be conceded this grace. Bless us all, without forgetting our dear schoolmistress, and kiss your scapular in the name of all of us.

Soledad Antolín[47]

Pedro Balda, Alkotz, 8 April 1983, p. 8; La Obra Máxima, September 1931, p. 281, and October 1931, p. 312.

These letters are little different from those of children in other schools in the magazine. But they share aspects with the subsequent visions: the children joining in a common sacrifice for the conversion of others; the role of the schoolteacher as a facilitator; the motif of the Eucharist; and the awareness of issues far beyond school and village. On 9 and 12 December 1931, at the height of their visions, these schoolchildren sent more money. One of the letters was signed by a twelve-year-old girl who was a visionary both at Izurdiaga and Ezkioga. The money was "to rescue a little pagan girl from the power of the devil" and have her named María Pilar. In a similar letter on behalf of the schoolchildren of Piedramillera dated 26 April 1931, twelve days after the Second Republic was

proclaimed, Lidia Gastón sent money for a "paganito" to be named Nicasio, "who is the patron saint of our village and to whom we fervently pray to intercede very extraordinarily in favor of our Spain, now in bitter and difficult straits." Magazines such as these and schoolteachers brought the children into the bigger picture.[48]

La Obra Máxima, May 1932, p. 150, and September 1931, p. 281.

The Izurdiaga seers were still having visions a year later on 11 September 1932 when Padre Burguera saw them in a chapel in a private home in Pamplona. There he marveled that the girl claimed to know that a certain flower came from a convent of nuns who were disbelievers. He describes the seers, much like those who followed Bernadette at Lourdes, running around on their knees unusually fast with their eyes fixed on a flower that they considered the Virgin as Burguera carried it from room to room and hid it from them. They subsequently underwent vision crucifixions, their vision lasting four hours in all. Sessions like these were held in these years in Pamplona convents, the asilo of the cathedral, and private houses, including the home of the parents of the Carlist leader Jaime del Burgo. There is no evidence that politicians in any way provoked the visions, but there can be little doubt that in Navarra the climate was propitious.[49]

B 167-169.

Finally, there were also little Ezkiogas in Gipuzkoa. One set of visions occurred simultaneously with the visions in Navarra in the fall of 1931 and indeed may have been a kind of replication of the Navarrese visions. At a house named Kaminpe, close to a road into Urretxu, child seers from the house itself and from Urretxu and Zumarraga gathered with parents and neighbors. The seers included siblings from three different families for a total of at least nine children, four boys and five girls, aged four to thirteen. Almost all of them had had visions at Ezkioga.

A woman who went as a spectator recalled that the seers distributed roses blessed by the Virgin. People lit large numbers of candles and the children fell down into a vision state and later chased the Virgin, who once hid from them under the sink. Once many people went up a nearby mountain when the children announced visions there; those attending included an invalid wrapped in blankets and riding in an ox cart and parents carrying sick or handicapped children.

One argument against the visions here was that the children who were seers later led lives just like the others—seer girls even rode bicycles, for instance. As a child aged seven or eight, my informant did not treat the visions of her playmates with the same importance that the grown-ups did. As in the Barranca, where the children sometimes played with holy dolls, it seems adults were taking seriously what for children had a component of fancy or play. But in any case the Kaminpe visions were a neighborhood affair; they did not attain in Urretxu the status of those in Navarra, which drew entire villages—and sometimes polarized them—for weeks or months. Presumably for the seer families it was simpler to go to Kaminpe than walk to Ezkioga, but later several children resumed visions at the main Ezkioga site.[50]

María Teresa Beraza, Hernani, 2 May 1984; Justa Ormazábal, Zumarraga, 10 May 1984, who was older, went twice.

Twenty-five kilometers from Ezkioga by road in the hills above Tolosa, Albiztur was a more durable satellite. In 1931, as today, it was a rural township with just a few houses near its church at the bottom of the valley and with farms on the mountainsides. The pious pastor, Gregorio Aracama, had prepared Albiztur's children and adults well to believe the Ezkioga visions. Deeply devoted to Mary, he dedicated his first sermon to her when he arrived in 1921 and put something about her in each sermon until he left in the late 1950s. Aracama asked parents to add the name María to the names of girls and boys he baptized, promoted Mary's month in May, and organized the sodality of San Luis Gonzaga for boys and the Daughters of Mary for girls. Before the visions, Aracama had led his parish in pilgrimage to Lourdes and had told and retold the Lourdes story in sermons. His sense of duty was so strict that when he heard a report of minor misconduct on the part of a girl, he was capable of going to her home to tell her parents. This alienated him from some families.

It was Aracama who arranged for a bus to take his parishioners to Ezkioga, and he went every Sunday. People from Albiztur went as early as 8 July 1931. An Albiztur girl, eight years old, had visions there on July 15; a second, thirteen years old, two days later; a third, fifteen years old and a sister of the first, on July 25; and a fourth, nine years old, on August 15. What they saw was retold in loving, enthusiastic detail in the Albiztur column of Argia by the local correspondent, "Luistar" (Juan Múgica Iturrioz), poet, barber, maker of espadrilles, and sexton. Like the priest of Izurdiaga, he too was the uncle of a seer. In his 2 August 1931 column he compared one of the girls to Bernadette. In subsequent visions, they saw the Virgin of Lourdes, Bernadette, and Bernadette's sheep.[51]

See Luistar, "Albiztur," in A: 19 and 26 July; 2, 9, 16, 23, and 30 August; 6 and 27 September; and 22 November 1931. His personal collection of Argia with handwritten corrections is in Instituto Labayru, Derio.

Three of the girls were from farms; the father of another worked in a pharmacy in Tolosa. There were, however, child seers of poorer people in the village. One of these, a girl whose father had only two cows and who worked in the quarry, first began to have visions in Albiztur proper. At the time, I think early 1932, she was caring for the baby of another family. She began to fall into vision by the road near the center of the village, and the woman who cared for the church went and prayed with her, attracting other followers. One day the schoolmaster chased them away, and they moved to the covered area of the church porch. Gradually more girls—only girls—began to have visions there, including three of those who had had visions at Ezkioga. Villagers can name ten, aged six to thirteen, who were seers. In this group were two leaders, an older one whose visions started late and especially the young one, the eight-year-old who had been the first to see at Ezkioga.

As elsewhere, the believers brought flowers that the seers redistributed in vision. The girls also saw the souls of the village dead and found out what prayers or masses they needed. Believers thought the girls could read unspoken thoughts and answer unspoken prayers, and I have talked to persons who were led to repent their sins in the sessions. People from neighboring towns went to

Albiztur seers posing on hillside above town. From VU,

30 August 1933. Photo by J. A. Ducrot, all rights reserved

see the children, but the sessions never reached the newspapers. The parish priest prayed discreetly at a distance, but afterward the girls went to his office and dictated what they had seen. These sessions coincided with outrage in the town over the removal of the image of the Sacred Heart from the exterior of the town hall.[52]

LC, 24 March 1932, p. 6, and 20 May 1932, p. 6.

Luistar, the sexton, was a Basque Nationalist. He was devoted to the Virgin of Lourdes, but not to the "Castillan" Virgen del Pilar. He went to Ezkioga fifty-three times starting on 8 July 1931. His last trip was on 30 June 1932, before the arguments of Laburu converted him from the visions' chief supporter to their chief opponent in Argia . The town as a whole split for and against the visions (the split eventually coincided roughly with the split between Carlists and Basque Nationalists), and little by little the girl seers and their families became isolated. "They thought we were fools," one steadfast believer told me.[53]

Luistar, A, 2 October 1932. He went on to write twenty pieces against the visions, the last on 1 October 1933.

In May 1933 the vision sessions on the church porch were still going on, with about thirty persons gathering at dusk to say the rosary and accompany the seers. By then the girls also held afternoon sessions at a little makeshift chapel their families had set up on the hillside above the village, at a site called Partileku. They posed there for J. A. Ducrot, the French photojournalist from the magazine VU . The bishop inevitably found out about the visions and threatened to deprive Aracama of his parish. So sometime in 1933 the girls stopped holding

the sessions in public. At least one girl continued in the intimacy of her family until 1940.[54]

For May 1933, Ducrot, VU, 30 August 1933; and for after that, relatives of girl seers from two houses, Albiztur, June 1984.

Each public mini-Ezkioga, like the "pre-Ezkiogas" of Torralba de Aragón and Mendigorría, had original aspects. In Albiztur all the seers were girls, in Bachicabo all were boys or young men, but in most places there were both boys and girls. In some places it appears that one seer led the others but that the leader might be older or younger. In some places local elites were sympathetic, and where there was a favorable priest or schoolteacher, the visions lasted longer. In some places, like Dorrao, Unanu, and Bachicabo, the Virgin insisted on worship outside the church. Certain divine beings, like Saint Rita, showed up more in one place than another. The Sorrowing Mary was common to many places, but Mary's avatars varied. Saint Michael and the Infant Jesus of Prague appeared more in the Barranca, where such devotions were strong.

There were also innovations in places. Invisible candy wrappers, the naming of five angels, a vision boulder, a Virgin who played hide-and-seek, visions as sermons, apparitions on house facades, and visionary flower designs were special twists that made each sequence of visions unique. And of course what made each unique was that the seers were members of the local population seeing divinities who had chosen that particular place and landscape.

Except for some sites of "unsuccessful" visions—the ones that drew no following—all these locations are rural. But the "successful" vision sites are well placed. Just as the visions of Ezkioga were just off a main highway, within a long walk of Zumarraga's three train stations, so the village vision sites were on or near main roads, many of them in or near village centers. Those in inconvenient places, like the Fuente Petrás of Bachicabo or the mountainside above Arbizu and Lakuntza, soon shifted.

As we will see for Ezkioga, however, the sites tended to incorporate emblematic elements of the landscape: a pine tree and a spring at Bachicabo; olive trees at Guadamura; a cave and spring at Orgiva; first a sacred mountain at Arbizu, then a walnut tree; pine trees at Dorrao and Unanu; a river a poplar trees at Bakaiku and Lakuntza; walnut trees at Iturmendi; a mountainside at Irurtzun, Albiztur, and above Kaminpe. When the visions were forced indoors the flowers remained as a link to the land.

The visions that were exclusively "urban," or architectural, as at Torralba, Mendigorría, Rielves, Guadalajara, and Sigüenza, were the most fleeting, perhaps in part because there was too much church and social control. The governor and the bishop of Palencia quickly checked a girl who in November 1931 tried to move her visions from the outskirts of the capital to a city church. In the provincial capital where public visions would have had the best chance, Pamplona, the bishop was too close for comfort. Conversely, in the cities of the north coast—Irun, San Sebastián, Bilbao, in all of which there were habitual seers—the hostile secular Republic was too close. In Tolosa sometime around 1933 two

middle-aged women of humble extraction were able to attract people to visions outside the town in a big meadow, where they placed a picture of the Virgin on a tree. But those visions lasted only briefly.[55]

El Día of Palencia had given ample coverage to Ezkioga and by mid-November 1931 the fourteen-year-old daughter of a building constructor was having daily visions of the Virgin, who arrived as at a séance preceded by loud knocks. The girl announced an apparition in the chapel of Our Lady of the Sorrows in Palencia for 10 A.M. on Sunday, November 22, just one hour before a public meeting of the anticlerical Radical Socialists, but the bishop refused to open the chapel and issued a statement dismissing the visions. All 1931: ELM, 20 November, p. 9; HM, 20 November, p. 4; El Día (Palencia), 24 November, p. 1; El Debate, 24 November, p. 1; ELM, 24 November, p. 9. At a vision session in or near Palencia in mid-May of the next year, an Ezkioga believer saw a girl, perhaps the same one, divide among the thirty or so persons present an apple she had received from the Holy Family. "Apariciones en Palencia," letter from Florentino Sánchez, Hornillos, 16 May 1932, typed excerpt, 1 page, private collection. For Tolosa, elderly male eyewitness, San Sebastián, 13 May 1986.

Almost all visions produced a reversal of power, with initiative and control in the hands of children or unmarried youths. And although this reversal coincided with an ancient southern European pattern, it may have had a particular significance for the period: the fear that the youth would lose their faith. By the same token, this fear may have provoked the marked increase in religious imagery directed at the young by missioners, parish priests, lay catechists, and schoolteachers. In the process, young and old alike became aware of the enhanced status of children in the distribution of religious power. Only in such an unusual ambience could a priest or schoolteacher have tolerated the kissing of child seers' hands, a youth seer's appointment of "angels," the use of a child seer's blessing to forgive sins, or the child's provision of sacred berries for healing. By obeying the minors, people were obeying and humbling themselves before the divinities for whom the minors spoke.

At Ezkioga, at center stage, as far as we know no one gave orders to harvest another's potatoes. The mini-Ezkiogas, however, were more domestic versions, like local-access cable studios rather than national networks. But within vision cuadrillas at Ezkioga, the same precise allotment of grace and favor took place, with flowers going to X and not Y and private messages delivered to certain persons in the knots of believers. The local seers of Navarra and Gipuzkoa were largely in synchrony with changes in vision motifs at the Ezkioga center. As at Ezkioga, struggles of Saint Michael and the devil occurred in the summer and early fall of 1931, seer crucifixions started in the winter of 1932, and seers' crucifixes "bled" in 1932 or 1933. There was clearly enough contact between the different groups to keep everyone up to date.