The Woodcuts

The same illustration blocks are used throughout the four editions. Their shape and dimensions clearly indicate that they were intended to be part of the pages of a book, and each is captioned in Latin cut into the block. The drawing, cutting, and rubbing of the blocks could have been done much earlier than the printing of the text and could, in sequence, have been separated by periods of time.

As determined by differences in the vertical measurement of the blocks on conjugate pages, a separate double-image block was cut for each page. The smooth framing arch and round column bases of the first two pictures of each chapter were probably designed to indicate that they were to be printed on the versos, or left pages, and the broken arch and plane-based columns indicated the rectos, or last half of the chapter (see figs. V-11 and V-12).

The few banderoles which were cut away to the borders, Chapters XXV b (p. 190) and XXIX d (p. 199) must have been left blank to be inscribed by hand. Would this indicate that the blocks were designed for a proposed chiro-xylographic book? But the letter-cutter has incised the lettering in the earlier block of the Annunciation in blockbook Chapter VII a (p. 154). In the copy of the Latin first edition in the New York Public Library (formerly the Inglis copy), and the one in the National Library in Florence, the banderoles of the last woodcut, Chapter XXIX d, for "Mene, Mene, tekel upharsin," are not cleared out and print as solid bands.[23] This must have been corrected, after a few rubbings, by clearing away to the borders as is shown by other copies of this edition. It is most unlikely that a chiro-xylographic book was planned, for the labor of writing the extensive text, as well as lettering the banderoles, would have been excessive for an edition of even moderate quantity.

It is generally agreed that there were two artists or woodcutters at work on the series. The first designed the pictures for Chapters I through XXIV, the next manuscript chapter is omitted, and in Chapter XXV of the blockbooks, a new artist is seen, or possibly only a new cutter. The architectural framing of the scenes and the solidly centralized or diagonally balanced compositions are very like those of the earlier chapters, but the form of the trees is rounded and the bodies are stockier, with broader heads. The hatchings for shading are frequently diagonal rather than horizontal. Finally, the figures are often larger within the frame.

Drawings were made, and blocks cut, for more of the manuscript chapters (if not all forty-five) than were used in printing the twenty-nine chapters of the blockbooks. Jan Veldener sawed in half all of the woodcuts (58 for 116 pictures) which appear in the books and used them in his Culemborg edition of the Speculum in 1483, together with eleven more by the artist/cutter of the later blocks (see our Chapter VII).

The first artist of the woodcuts either was a known Netherlandish master of the period or worked in his atelier. Mention has been made in Chapter I of the magnificent Book of Hours

[23] C. Doudelet, Le Speculum Humanæ Salvationis à la Bibliothèque Nationale de Florence (Ghent and Antwerp, 1903), p. 39.

V-16.

The Hours of Catherine of Cleves.

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, M. 945, f. 78, compared with

Speculum humanæ salvationis blockbook, Chapter XIX c (detail).

of Catherine of Cleves, which most art historians agree was completed about 1440.[24] The manuscript contains several miniatures which in their style and subjects show that the illuminator was aware of the woodcuts of the Biblia pauperum and the Speculum humanæ salvationis or of lost models which may have been used for both the blockbooks and the miniatures in a closely knit community of book producers. There is a version of the goat nibbling the grapes in the Speculum woodcut of the Shame of Noah (Chapter XIX c) which in size and drawing is very close to the illumination in the Cleves manuscript.

[24] For discussions of the Book of Hours of Catherine of Cleves, see the following: L. M. J. Delaissé, A Century of Dutch Manuscript Illumination (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1968); John Plummer, The Hours of Catherine of Cleves (New York, 1966); Friedrich Gorissen, Das Stundenbuch der Katharina von Kleve (Berlin, 1973).

The possibility must also be accepted that the artist of the blockbooks was influenced by the Cleves miniatures rather than the reverse. Since the workshop where the Hours was made is known to have continued production through the middle of the century, it may be that an artist from the circle of the Cleves Master was actually involved in designing the woodblocks of the Speculum.[25] We may hope that further explorations by art historians and bibliographers will reveal more about the connection between the contemporary manuscript illumination and the Speculum blockbooks.

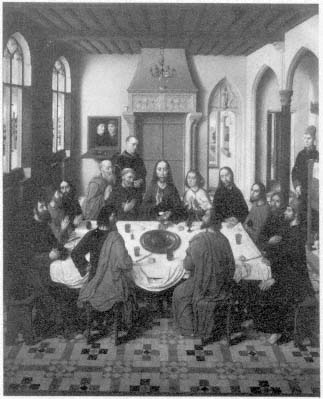

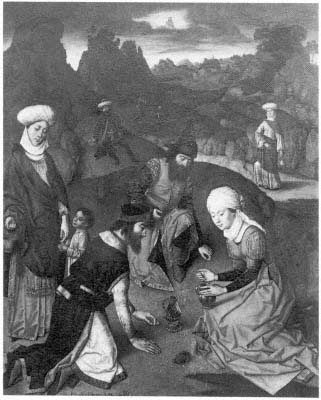

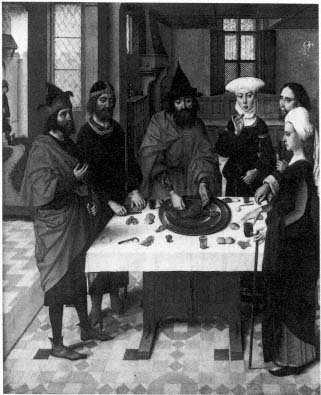

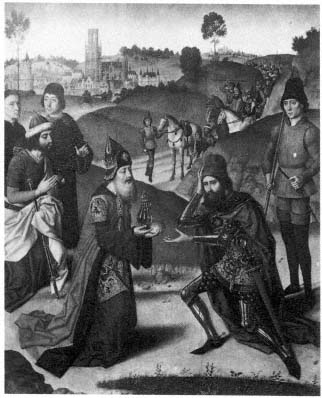

A relationship has long been assumed between the Altarpiece of the Blessed Sacrament painted by Dirck Bouts (c.1415–1475) for the church of St. Pierre in Louvain and the blocks for Chapter XVI of the Speculum .[26] In 1464 a contract was executed by which the Confraternity of the Holy Sacrament of Louvain, a group of wealthy burghers organized for pious and charitable purposes, commissioned Dirck Bouts to paint a triptych for the larger of their two chapels in the choir of St. Pierre. It was to be dedicated to the Eucharistic rite, which had enormous popularity at the time, and the Brothers chose two theologians to inform Bouts on the subjects and arrangement of the panels. They based the iconography of the triptych on the Speculum humanæ salvationis , which had been widely accepted as an authoritative work for more than a century.

Bouts' triptych depends on the pictures of the blockbook not only in the selection of the subjects but also in the general compositions of the five scenes. They have been enriched by many details. Portraits of the theologians and possibly the artist himself are included in the central panel of the Last Supper.[27] In the Eating of the Paschal Lamb, on the table are the type of glasses made in the Meuse and Brabant regions.[28] The painting of the Gathering of the Manna draws its concept of the Heavenly Bread from the biblical description: the manna is "small as the hoar frost on the ground" (Exodus XVI: 14). The pitchers used for gathering it are of the same shape as those in the Speculum blocks and are probably typical of that period and location. If the Bouts triptych did depend on the blocks (and we know of no manuscript miniatures with these same compositions), the dating of the first edition at 1468 on the evidence of watermarks is thus brought into question, for the blockbook must have existed before the 1464 contract.

[25] Robert G. Calkins, "Parallels between Incunabula and Manuscripts from the Circle of the Master of Catherine of Cleves," in Oud Holland, XCII (1978), p. 147 and p. 160, fn. 33. See also James Marrow, "A Book of Hours from the Circle of the Master of the Berlin Passion: Notes on the Relationship between Fifteenth-Century Manuscript Illumination and Printmaking in the Rhenish Lowlands," in Art Bulletin, LX, 4 (1978), pp. 591–616.

[26] Doudelet, op.cit. , p. 11.

[27] Shirley Neilsen Blum, Early Netherlandish Triptychs . (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1969), p. 66.

[28] Flanders in the Fifteenth Century: Art and Civilization , Catalogue of Exhibition, edited by E. P. Richardson (Detroit, 1960), p. 107.

The triptych of the Blessed Sacrament is thought to be the first panel painting of this subject to be done in the Netherlands and its focus on the act of Communion, in the central panel, was unusual. Bouts appears to have worked with Roger van der Weyden on the angels for the vault of one of the chapels of the church of St. Pierre[29] before undertaking the commission for the altarpiece. Both Bouts and Van der Weyden are known to have had strong relationships to the Groenendael community of the Devotio moderna .

We have discussed in Chapter IV the production of blockbooks, specifically the Spirituale pomerium and the Exercitium super Pater Noster , at Groenendael, or possibly at Sept-Fontaines, or both. We have outlined the great importance of the many houses associated with the Devotio moderna in fifteenth-century book production in the Low Countries. We know that they contained woodcutters, illuminators, scribes, miniaturists, and binders. They were also, we assume, in somewhat the same position as a publishing house, i.e., they chose the texts, selected the artists or ateliers for the illustrations, commissioned the text printing, and distributed the editions. The production of two of the editions in Dutch, and the use for which they were intended, strongly suggests that the blockbook editions of the Speculum can be linked with the houses of the Devotio moderna . It also seems logical that the woodblocks remained in the possession of one of the communities (probably Groenendael or Brussels) where Veldener could have seen them when he set up his press nearby in Louvain, in 1475, or before he left for Utrecht in 1478 (see our Chapter VII).

While the name of the printer, the place, and the dates of the printing of the Speculum blocks or text cannot, as yet, be determined, the continued research of art historians, bibliographers, and typographers may combine to solve these mysteries.

[29] G. Hulin de Loo, "Sur la biographie de Dieric Bouts avant 1457," in Mélanges d'histoire offerts à Henri Pirenne (Brussels, 1926), pp. 257–62.

V-17.

a. The Last Supper.

b. The Gathering of the Manna.

c. The Jews Ate the Paschal Lamb.

d. Melchizedek Offered Abraham Bread and Wine.

Speculum Humanæ salvationis blockbook, Chapter XVI.

V-18.

The Last Supper.

The Gathering of the Manna.

The Jews Ate the Paschal Lamb.

Melchizedek Offered Abraham Bread and Wine.

Retable of St. Pierre at Louvain.

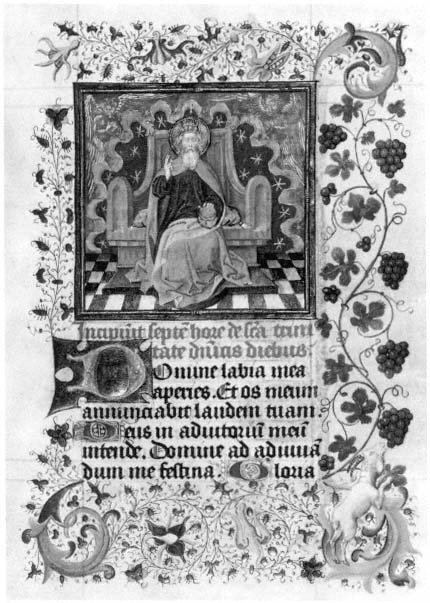

VI-1.

Typical page from Speculum blockbook Edition IV.

Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino, California, Xyl. H-C, 14924.