The Regime Cracks Down

In July 1969 judiciales, combined with agents from the Department of Interior Affairs, the Defense Department, and local officials, launched the "first combined hunt" for what El Universal headlined as "Vicious 'Hippies.'" Sixty-four Mexicans belonging to the Tribe of Christ commune, along with twenty-two foreigners caught in the raid, were arrested; all were officially charged with trafficking drugs. The foreigners—seventeen from the United States, four from Canada, and one from England—were promptly deported (see Figures 7 and 8).[37] Two days later El Universal

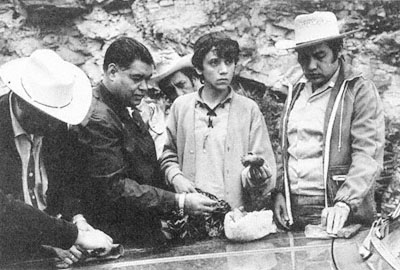

Figure 8.

Foreign hippies (probably from the United States) face the prospect of ar-

rest and deportation following a raid on Huautla de Jiménez, Oaxaca, in July 1969.

Source: "Concentrados: sobre 1303, 'Hippies [mugrosos gringos de la época],'

July 1969," Hermanos Mayo Photo Archive, Archivo General de la Nación. Used

by permission.

warned of the "grave dangers" facing Mexico because of the "contamination of our youth" by North American hippies.[38] The arrests were just one aspect of a wider crackdown. Jasmín Solís Gómez, the informant cited above, was in Huautla when she too was caught up in a raid: I heard shots, shouts, and beatings and didn't know what to do.... They marched [the three Canadians and me] back to Huautla."[39] While police actions against foreign and Mexican hippies were well known prior to this, the federal orchestration of the arrests suggested the utility of highlighting the jipismo "threat" in the wake of Tlatelolco (see Figure 9).

Focusing government attention on the rise of jipismo not only distracted from the larger issues of reform and repression but, moreover, facilitated a strategy of conflating antigovernment protest with jipi radicalism.[40] By implementing a repressive policy against native and foreign hippies, the government sought to bolster support among conservative social groups such as small shop owners, middle-class parents, and, especially, rural and

Figure 9.

Caught with hallucinogenic mushrooms, a Mexican jipi faces the pros-

pect of arrest during a bust in Huautla de Jiménez, Oaxaca, in July 1969. Source:

"Concentrados: sobre 1303, 'Hippies [mugrosos gringos de la época],' July 1969,"

Hermanos Mayo Photo Archive, Archivo General de la Nación. Used by permission.

provincial populations who felt threatened by the challenge to traditional family values—work discipline, respect for authority, gender distinction—embodied in jipismo. A central feature of the government's strategy was thus to rally sentiments of xenophobia and nationalist pride, a tactic which also overlapped with the official position that the student protesters were backed by "foreign agitators." Capturing this sentiment of support for the federal offensive against the "contamination" of Mexico by North American hippies is the August 1969 cover drawing for Jueves de Excélsior: a man with his shirtsleeves rolled up, broom in hand, sweeping a contingent of (male) hippies back across the border (see Figure 10).[41]

Mexico was not alone in its struggle to combat its "hippie problem." Many governments were forced to confront the influence of a U.S.-led counterculture on a generation of young people who refused to conform to their nation's ideological project of development, whether oriented toward capitalism or socialism. In Singapore, for example, entry was prohibited to tourists who wore "ornaments and clothes which leave one with the unmistakable impression that this is part of the contemporary aberrations found in the highly developed and affluent societies and imitated by not so

Figure 10.

"Cleanup of 'Hippies' and Drug Addicts." Source:

Jueves de Excélsior, 21 August 1969. Used by permission.

highly developed and affluent societies."[42] In the Soviet Union, the state was obliged to declare the "legality" of long hair, a tacit recognition of its inability to pursue a totalizing socialist project.[43] For governments the world over, the "hippie problem" suggested a fundamental crisis of representation: "dropping out" of society, reflected through one's dress, language, and attitude openly challenged the ideological premise of the heroic nationalism that characterized most post-World War II states. While in reality the hippie presence in most countries was never more than a minority, for an entire generation of modern, urban-raised youth throughout many parts of the world the power of the hippies' appeal—to "do one's own

thing"—presented an unforeseen and complex new threat to national-developmentalist projects.

Despite drastic efforts by the Mexican regime, however, the flow of foreign hippie travelers into the country seemed unabated. An editorial that appeared one year after the Huautla raid cited the "need for a new, even more energetic intervention by the army and federal police" to stop the continued influx of hippies: "If the Secretary of Interior Affairs doesn't put a stop to the immigration of undesirables, soon we will have to support spectacles of homosexuality, massive drug addiction, and street violence, similar to what citizens of San Francisco, New York, London, and other large urban centers face."[44] These fears directly contributed to a public backlash against jipismo and led to heightened efforts by border guards to keep foreign hippies out. Judging from a report in Rolling Stone magazine, the problems facing hippies traveling to Mexico were taking their toll. "They don't like longhairs in Mexico," the travelogue opens. "If you are a man and your hair falls below your collar, expect to be—at least—stared at as if you were a civil rights worker in Mississippi, and—at worst—robbed or beaten by policía as well as bandidos."[45] Indeed, The People's Guide contained a special section dedicated to "Border Hassles," which stated in part: "If you do not look like the average tourist (and you longhaired, bearded, beaded and braless people have already guessed that there was a catch somewhere), you may not get average treatment when entering Mexico.... Mexican border officials have a straightforward attitude: people without money are hippies and therefore less desirable as tourists.... People with money are not hippies, even though they may affect hippie styles."[46] To beat the system, Carl Franz, the book's author, suggested a temporary fix of dress and presentation: "We look like small town teachers or college students from the early Sixties [when we cross]." He added, "The border officials love it."[47]

Though official sources that treat this theme are difficult to come by, one record found in the archive of the Department of Foreign Relations reveals the extent to which antihippie policy had reached the highest levels of power. The Mexican consul in San Diego came across an article in a local newspaper that described the difficulties facing U.S. hippies in Mexico. He forwarded a copy of the article to Mexico's secretary of foreign relations, who, in turn, forwarded the report to the appropriate authorities at the Department of Interior Affairs, with the accompanying message: "For whatever importance it might mean for this Dependency of the Executive [that is, Interior Affairs], with the present note is remitted a newspaper clipping from the 'San Diego Union,' which was sent to us by our Consul in San

Diego, California [regarding] the publishing of an extensive article warning North American drug-addicted youth about the obstacles they will come across [when] penetrating our country to dedicate themselves to their cravings."[48] Whether or not this message went into a larger file at the department is uncertain, though probable; access to its archives is still restricted. At any rate, Mexican officials were by no means alone in their fight against foreign hippie influence. When later "banned" from Lamu Island, Kenya, for disrupting village life, for example, Jerry Hopkins, writing in Rolling Stone magazine, blithely concluded: "The search for paradise continues."[49]

Some U.S. citizens even expressed their support for the stepped-up repression against hippie youth by the Mexican government. In a letter to President Díaz Ordaz, one writer stated: "May I offer my sincere congratulations on the stand you have takened [sic ] regarding the long haired, hippie type, individual or so called? [sic ] citizen, of our side of the border. Speaking for myself I am ashamed of their appearance."[50] Another person wrote, "I wish our government had the backbone to take a stand against such un-Godly, trashy mess as you have."[51] These letters suggest a projection of frustrations with the "hippie problem" in the United States onto the more "efficient" regime in Mexico. Moreover, they follow a pattern of support for Mexico's policy of repression against dissidents in general. Thus the author of the last letter concurred with the harsh approach to protesters, saying in conclusion: "I believe we could put a stop to riots here, as you did when they tried to prevent the Olympics from being held in Mexico. I have never [heard] of any more riots in Mexico."[52]