Conclusion

The story of Qazi Amin’s coming of age bears a certain resemblance to the story previously told of Samiullah Safi’s formative years. Both men had strong fathers who were immersed in venerated traditions that their sons initially sought to follow. But while both men were born into the world their fathers had known, that world changed as they came of age. One feature of that change was the unbalancing of the tripartite relationship of state, tribe, and Islam that had long been the foundation of Afghan political culture; in the second third of the twentieth century that relationship had begun to tip lopsidedly in favor of the state. Growing up, Qazi Amin and Samiullah Safi had an idealized faith respectively in Islam and tribal honor, but their experience and education led them both to believe that they could no longer continue on the paths laid out for them by their fathers. It was not enough to be a religious teacher or tribal chief. The expansion of the state made the very existence of those positions tenuous, and so both sought new venues within which to redirect the state’s power. For Samiullah Safi, that venue was the parliament, which he viewed as the best place to push the state to become more responsive to the needs of the people. Going against the advice of his father, he ran for and was elected to parliament, but he found there a body of men all speaking for themselves with little commitment either to the institution itself or to the principles of democratic representation. When that institution was disbanded following Daud’s coup d’état, Samiullah began a long period of inactivity that ended when a second Marxist coup d’état gave him a second chance at reconciling the disparate strands of his life.

Qazi Amin’s story diverges from Samiullah’s somewhat in that the venue he chose for keeping alive the faith of his fathers was a political party of student peers. Qazi Amin made this choice at a time when the ulama were generally complacent or ineffectual in the face of growing challenges to and indifference toward religion, particularly within the urban elite. In an earlier age, someone like Qazi Amin probably would have become the head of a madrasa, a judge, or a deputy to one of the major Sufi pirs in the country, but religious education and Sufism were both in decline when he was a young man. The great Islamic leaders of old were dead, and most of those who inherited their sanctity as birthright were either content with the wealth handed down to them or ensconced on the government payroll. The choice for Qazi Amin was either to take the job offered to him and ignore the larger problems he perceived in the country or to seek a new institutional setting within which to defend Islam. The interstitial space of the university campus allowed the formation of novel sorts of groupings—students of Islamic law with engineers, Pakhtuns from the border area with Tajiks from the north, Sunnis with Shi’as, and all of them young people, unrestricted by the usual protocols of deference to elders.

Kabul University offered a context for youthful political zeal different from any that had existed before; it is probably not an exaggeration to state that at no other time or place was such a diverse group of young Afghans able to meet together and to formulate its own ideas, rules of order, and plans for the future without any interference from those older than themselves. Some of the senior members of the Muslim Youth did have connections with faculty mentors. Abdur Rahim Niazi, in particular, was reported to have had close ties with Professor Ghulam Muhammad Niazi, who had spent some time in Egypt, where he had been acquainted with members of the Muslim Brotherhood, the prototype for many radical Islamic parties. However, presumably because they held government positions that could be taken away, Professor Niazi and other faculty members limited their role to private meetings with a few student leaders and never came out publicly in support of the student party. This reticence severely restricted their influence and also meant that as the confrontations on campus heated up, no moderating influence was available to push compromise or reconciliation. In certain respects, this experience was a liberating one, and it allowed new winds to blow into the ossified culture of Afghan politics. However, unhinged from traditional patterns of association, the student political parties were ultimately a disaster for Afghanistan, for as they were cut off from the past, living entirely in the cauldron of campus provocations and assaults, student radicals developed a political culture of self-righteous militancy untempered by crosscutting ties of kinship, cooperation, and respect that elsewhere kept political animosities in check.

The Muslim Youth, like their contemporaries in the leftist parties, abandoned (at least for a time) the ancient allegiances of tribe, ethnicity, language, and sect on which Afghan politics perennially had rested. In their place, young people took on new allegiances, professing adherence to ideological principles they had encountered only weeks or months before and swearing oaths of undying fealty to students a year or two older than themselves. These loyalties were kept alive through a paranoid fear of subversion. Only other members could be trusted; every other person was a potential spy, an enemy out to destroy the one true party of the faithful. Marxists and Muslims were tied together in ways they did not recognize at the time. Sworn enemies, they also needed—and ultimately came to be mirror images of—one another, linked together by their tactics, their fears, their confrontations, and their self-righteousness. Each believed that its enemies were wrong, that they alone held the key to Afghanistan’s future. Each side also believed that violence in advancement and defense of a cause such as theirs was appropriate and ultimately necessary.

The religious moralism and suspicion that first took root in the soil of the new democracy at Kabul University reached its full flowering a decade later in Peshawar with the rise to power of Hizb-i Islami. The constant attention to the behavior of others that was evident in the first generation of Muslim student activists was extended in the second generation, as Hizb members watched how they and others dressed—Hizbis could be identified by the neatness of their clothing and the white skullcaps (jaldar) that most wore—how long they and others wore their hair and beards, and whether and how often they attended mosque and which mosque they frequented. In Kabul, there had been an element of play in the actions of the Muslim Youth. They were engaged in a game of “gotcha” with Marxist students that was played in the insulated confines of the university campus. After the coup in 1978, however, the game turned deadly serious, and the monitoring that went on in Peshawar was no longer associated just with party promotion but with disgrace and sometimes assassination.

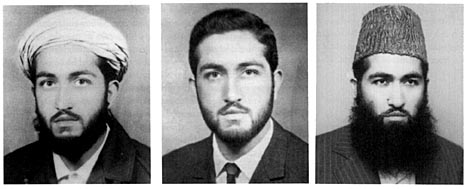

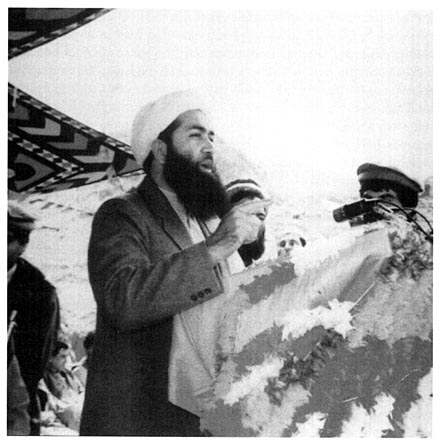

The evolution of Qazi Amin’s increasingly revolutionary persona can be glimpsed in the three photographs contained in Figure 11. The photographs are all studio shots taken at different stages of Qazi Amin’s early life—the first when he was a taleb in his late teens at the Hadda madrasa; the second when he was a student in his early twenties at Kabul University; and the third when he was in his thirties and a leader of Hizb-i Islami. The three photographs, which Qazi Amin provided to me, are simple head shots of the type that could be used for an identity card. In the first, he looks like a typical madrasa student, with a sparse, patchy beard and cheap cotton turban. The second photograph shows a man more concerned with his appearance. The turban is gone. His hair is neatly combed and the beard trimmed close to his face. The coat and tie were common in pictures of university students of that period, but the beard also tells us of his commitment to Islam, as more secular students almost always favored a mustache or clean-shaven look. In the third photograph, the suit coat remains, but the tie—which is identified with Western fashion—has been jettisoned. Though we cannot see the rest of his clothes, it is likely that the Western-style trousers he wore at the university have been replaced by traditional pantaloons (shalwar). On his head is the sort of karakul cap favored by mid-level Afghan government officials, which the man in the picture could be were it not for the full, untrimmed beard. This is the look Qazi Amin continued to favor in later years, except that the karakul cap was replaced by turbans—sometimes white, in the fashion of Muslim scholars, sometimes of the dark, striped sort worn by Afghan tribesmen (Fig. 12).

11. Qazi Amin (courtesy of Qazi Amin).

12. Qazi Amin speaking at the dedication of a new high school, Kot, Ningrahar, post-1989 (courtesy of Qazi Amin).

Perhaps more interesting in these photographs than the changes of look and style is the set of the eyes. The boy in the first photograph looks at the camera with guilelessness, his eyes wide; perhaps he is facing a lens for the first time. The young man in the second photograph seems at once more self-confident and earnest but also more affected and aware of his appearance. His back is noticeably straighter, and one suspects that he is looking not only at the camera but also at his future. The third man is identifiably the same person as in the other photographs, but he has gained a solidity that was absent before. That solidity derives partially from the fact that he is heavier now and has a longer, darker beard that curls out from his cheeks and down over his collar. It derives also from the lambskin cap, which seems to push down on his head. But even more it comes from the look in his eyes—fierce, resolute, and unwavering. This is not a man who you would imagine spends a lot of time laughing. It is a man focused on the task in front of him, a man used to making decisions and ordering other men around. It is also a man of conviction—a man determined in his course of action, a revolutionary.